Abstract

Birth trauma and pelvic injury have been implicated in the etiology of stress urinary incontinence (SUI). This study aimed to assess changes in the biomechanical properties and adrenergic-evoked contractile responses of the rat urethra after simulated birth trauma induced by vaginal distension (VD). Urethras were isolated 4 days after VD and evaluated in our established ex vivo urethral testing system that utilized a laser micrometer to measure the urethral outer diameter at proximal, middle, and distal positions. Segments were precontracted with phenylephrine (PE) and then exposed to intralumenal static pressures ranging from 0 to 20 mmHg to measure urethral compliance. After active assessment, the urethra was rendered passive with EDTA and assessed. Pressure and diameter measurements were recorded via computer. Urethral thickness was measured histologically to calculate circumferential stress-strain response and functional contraction ratio (FCR), a measure of smooth muscle activity. VD proximal urethras exhibited a significantly increased response to PE compared with that in controls. Conversely, proximal VD urethras had significantly decreased circumferential stress and FCR values in the presence of PE, suggesting that VD reduced the ability of the proximal segment to maintain smooth muscle tone at higher pressures and strains. Circumferential stress values for VD middle urethral segments were significantly higher than control values. Histological analyses using antibodies against general (protein gene product 9.5) and sympathetic (tyrosine hydroxylase) nerve markers showed a significant reduction in nerve density in VD proximal and middle urethral segments. These results strongly suggest that VD damages adrenergic nerves and alters adrenergic responses of proximal and middle urethral smooth muscle. Defects in urethral storage mechanisms, involving changes in adrenergic regulation, may contribute to stress urinary incontinence induced by simulated birth trauma.

Keywords: incontinence, innervation, biomechanics, smooth muscle, phenylephrine

women of all ages are affected by urinary incontinence (28). Furthermore, Americans spend millions of dollars attempting to cope with stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (26). Various surgical methods and injections of bulking agents into the urethra have been used to treat SUI. These methods and pharmacotherapy have had limited success (1, 34). Adrenergic agonists have been considered as a possible treatment for SUI because sympathetic adrenergic nerves are abundant in the urethra and α1-adrenergic receptors are thought to play a major role in the contraction of the urethral circular smooth muscle (2). However, nonselective α1-adrenergic receptor agonists have proven to have only limited clinical efficacy due to cardiovascular side effects (27).

With the use of a model of simulated birth trauma in a female rat, several studies have established that damaged muscle fibers (4, 20), apoptosis (31), decreased innervation (20, 33, 35), and altered extracellular matrix components (8, 32) are associated with a significantly lower leak point pressure and sneeze-induced urethral pressure responses in vivo. Previously, our laboratory (30) has verified that there is a lack of basal tone in the urethra of rats subjected to VD, as well as an increased proximal urethral compliance in the passive state where muscle activity was eliminated by removal of extracellular calcium. The changes in passive properties were hypothesized to be due to alterations in the extracellular matrix. Similar findings have been reported by other investigators (32).

To fully assess the effect of VD on urethral musculature, it is also important to evaluate the tissue in the active as well as the basal and passive states. In the active state, the smooth muscle is precontracted with neurotransmitters or agents that directly stimulate the muscle contractile mechanisms so that muscle activity can be evaluated biomechanically. While there have been many attempts to characterize the urethra ex vivo in the presence of an adrenergic agonist, not many studies have examined the changes in agonist-induced responses following VD, because of the lack of well-characterized models for birth trauma and the inability of existing ex vivo systems to fully characterize and mimic the geometry and activity of the urethra in vivo.

The aims of this study were to assess the effects of VD on basal and α1-adrenergic receptor agonist-induced smooth muscle contractions in the proximal, middle, and distal segments of the urethra under sustained (8 mmHg) and increasing increments of static intralumenal pressure (0–20 mmHg). Additionally, we examined whether the observed VD-induced functional changes were correlated with changes in nerve fiber density determined by histological analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g, ∼8–12 wk of age; Harlan, Scottdale, PA) were housed at the University of Pittsburgh under the supervision of the Department of Laboratory Animal Resources. The policies and procedures of the animal laboratory are in accordance with those detailed in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Procedural protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animal Model and Urethral Harvest

Animals underwent vaginal distension (VD) using a protocol previously reported (17). In short, female rats were anesthetized with halothane (2%) in oxygen. A 5-ml 10-Fr Rusch-Foley balloon catheter was inserted into the vagina and was inflated with 4 ml of water. Distension was maintained for 3 h.

Four days later, animals were anesthetized and an intralumenal catheter (PE 50 Intramedic tubing; no. 42741; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) was inserted through the urethra into the bladder. The bladder and the distal external urethral meatus were ligated around the catheter with a silk suture (4–0). The ureters were tied off to prevent leakage and to serve as anatomical landmarks for in vivo length measurement. The maintenance of in vivo length is important since the tissue is anisotropic (24), and it is necessary to account for animal-to-animal variability; thus all tests were standardized by keeping each specimen at its own specific in vivo length. For transport, excised urethral specimens were placed in cold media 199 that was previously bubbled for a minimum of 30 min with a gas mixture (95% O2-5% CO2) to prevent anoxia.

Pharmacological and Biomechanical Studies

Specimens were assessed using an ex vivo urethral testing system, described previously (15). Briefly, intact urethral specimens were mounted onto the tees of the ex vivo testing system, and a hydrostatic pressure reservoir was manually displaced along a calibrated ringstand to apply intralumenal static pressure via a column of media 199. Specimens were also bathed externally in media 199 (no. M3679; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Outer diameter (OD) measurements were acquired with a helium-neon laser micrometer (Beta LaserMike, Accuscan 1000, Dayton, OH).

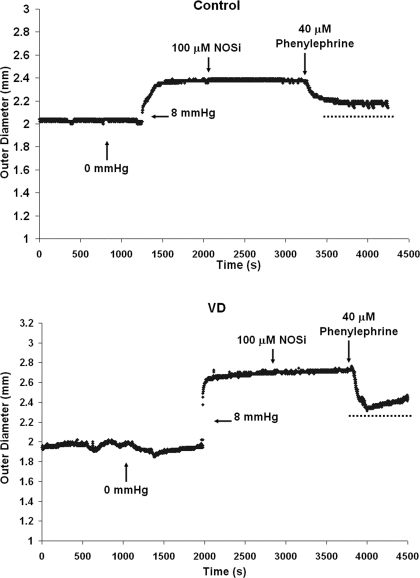

Contractile responses of the urethral smooth muscle were evoked by administration of phenylephrine (PE; no. P6126, Sigma Chemical), an α1-adrenergic receptor agonist. For these experiments, the urethra was exposed to a fixed intralumenal pressure of 8 mmHg, which caused the tissue to dilate to a constant outer diameter (OD8mmHg) and allow for a measurable amount of contraction to take place. Following the addition of muscle-responsive agents, the new OD was measured, which allowed the determination of the relative percentage change in outer diameter (%OD). The agents used to test the tissue in the active state were added consecutively to the external bath (Fig. 1): 100 μM Nω-nitro-l-arginine (NOSi; Ref. 40), a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor (no. N5501; Sigma Chemical), and 40 μM PE (14), a nonselective α1-adrenergic receptor agonist.

Fig. 1.

A depiction of the regimen for smooth muscle activation via phenylephrine (PE). Initially, a baseline outer diameter (OD) was achieved at 8 mmHg, and a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor (NOSi) was added to inhibit endogenous release of nitric oxide. PE was added to contract urethral smooth muscle via α adrenergic receptors; representative tracing for control (top) and vaginal distension (VD; bottom) proximal segments is shown. Average %OD response values are summarized in Table 1.

Once the tissue was fully contracted, the pressure was decreased from 8 to 0 mmHg intralumenal pressure. The tissue was then subjected to stepwise increases in pressure ranging from 0 to 20 mmHg in 2-mmHg increments. Each pressure step was maintained for 10 s to ensure that the testing occurred during the duration of muscle contraction. Data were recorded with a sampling rate of 20 Hz. Following active biomechanical testing, 3 mM EDTA (38), a calcium chelator, was added to assess the amount of basal tone present. The fractional response of the urethra was calculated in terms of %OD:

| (1) |

where ODDrug represents the diameter response to each pharmacologic agent and OD8mmHg is defined as the baseline diameter measured at an intralumenal pressure of 8 mmHg before addition of any pharmacological agent. Calculations for %OD were performed for the maximal diameter response to PE and EDTA, taken as the average of 100 data points. Maximum diameter responses from 8 mmHg were calculated using Eq. 1, except the difference between OD8mmHg and OD0mmHg was normalized to OD0mmHg. Comparisons were made between control and VD urethras.

After EDTA was added, pressure was returned to 0 mmHg and the tissue was assessed for passive biomechanical properties. For evaluation of the passive state, tissue was first preconditioned by supplying 10 cycles of intralumenal pressure with each cycle ranging from 0 to 8 mmHg and applied over 20 s. This was followed by subjecting the urethra to 2-mmHg increments of intralumenal pressure ranging from 0 to 20 mmHg. Each pressure step was maintained for 1 min. Data were recorded with a sample rate of 5 Hz.

To test proximal, middle, and distal segments on one urethra, specimens were washed three times with media 199. Each wash was sustained for 15–20 min to ensure that any pharmacological effects from the previous assessment would not have a residual effect, which was confirmed with assessment of the control middle segment with three sequential applications of PE (data not shown). Additionally, responses of both normal and VD urethras were measured in random order at proximal, middle, and distal segments of the urethra following addition of drugs.

Biomechanical Parameters

Circumferential stress and strain values were calculated at each pressure step using the pressure-diameter data and the histological thickness, as described previously (14, 30). If the urethral specimens are assumed to be thick-walled, linearly elastic, isotropic cylinders, the circumferential stress (σθ) at any point r through the thickness of the wall may be estimated by:

| (2) |

where r = 0 at the center of the lumen, r = Ri at the inner wall surface, and r = Ro at the outer wall surface.

Circumferential strain, εθ, is defined by:

| (3) |

where ΔR̄ is the change in the mean or mid-wall radius (R̄ = Ro + Ri/2) from its unpressurized value, R̄. Utilizing the incompressibility assumption, thickness was evaluated with histology, as described previously (30).

To compare the circumferential stress between control and VD groups, the stresses in the same strain range needed to be known (29). Thus each calculated stress-strain curve was fit to a third order polynomial for active curves. Strain ranges were chosen for low, middle, and high strain values for control and VD urethras. This was achieved by pooling circumferential strain data for proximal, middle, and distal segments separately and determining the maximum and minimum values. Fits were performed with the statistical software package, SPSS (version 15.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). This procedure was performed for all active biomechanical procedures.

Fridez et al. (10) developed a method to assess the contribution of smooth muscle activity to vascular wall properties. This method was adapted for the urethral wall so that muscular changes in the urethral wall post-VD could be detected. The functional contraction ratio (FCR) index is a nondimensional index that depicts the relation of pressure to the contraction of the urethra and its passive response. Plotting the FCR vs. static pressure provides an insight into muscle behavior with increasing pressure. FCR was calculated using:

| (4) |

where ΔDn represents the difference between active and passive OD measurements at each respective pressure and Dp is the corresponding passive OD measurement at each pressure.

Immunostaining for Protein Gene Product 9.5 and Tyrosine Hydroxylase

For analyses of neural changes after VD, control (n = 7) and VD (n = 7) urethras were analyzed with antibodies against protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5; rabbit polyclonal antibody; no. YBG78630507; Accurate Chemical, Newbury, NY) to assess general nerve damage. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, specimens were subjected to 30% sucrose solution in PBS for 24 h. Before embedding, 1- to 2-mm segments were separated for proximal, middle and distal segments (30, 50, and 70% of in vivo length). This was performed for seven specimens in the control and VD groups separately. Tissue sections for immunohistochemical analyses were cut via a cryostat with a thickness of 10 μm. One section per segment (proximal, middle, and distal) for each specimen was evaluated.

PGP 9.5 is highly specific for an enolase expressed in all peripheral nerves. Sections were washed in PBS several times for 10 min each. The antibody was diluted to 1:1,000 in a PBDT solution, composed of PBS, 0.03% Triton, and 2% donkey serum (no. 017–000-001; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Sections were incubated with the diluted primary antibody overnight at 4°C and then washed in PBS several times for 10 min each. Secondary antibodies [cy3, IgG fragment f(ab)2 donkey anti-rabbit; no. 711 165 152; Jackson Laboratories] were diluted to 1:800 in PBDT and applied to tissue sections for 2 h at room temperature. Slides were rinsed with PBS, dried, and coverslipped with aqueous mounting medium.

Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) is a marker for nerves that releases catecholamines and is the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of the amino acid l-tyrosine to dihydroxyphenylanine (DOPA). DOPA is a precursor for dopamine and for norepinephrine (18). Sections were rinsed with PBS several times for 10 min each followed by an incubation in PBDT for 45 min at room temperature. Sections were then incubated in a diluted primary antibody (1:1,000; mouse TH antiserum) for 24 h at 4°C and then rinsed with PBS. The secondary antibody [cy3, IgG fragment f(ab)2 donkey anti-mouse; no. 715 166 151; Jackson Laboratories] was added at a concentration of 1:1,000. Sections were incubated with the secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature, then rinsed with PBS several times, and coverslipped with aqueous mounting medium.

All microscopic images were acquired with a color digital camera (no. DP12; Olympus, Dulles, VA) attached to an Olympus microscope (model BX45) and captured using MagniFire Software (no. DP12; Olympus). The images of each urethral cross section were then imported in Scion Imaging software (version 0.4.0.3; Scion, Fredrick, MD). For quantification of positive stain for PGP 9.5 and TH, pictures were taken at four positions around the urethra (12:00, 3:00, 6:00, and 9:00 o'clock) at ×20 magnification. Percent area of positive stain was calculated by:

| (5) |

where Astain is defined as the area of positive stain measured and Atotal is the total area of the urethral position measured. For analyses, any positive staining in the urothelial (innermost) layer was omitted to focus on nerve density in smooth muscle.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical comparisons were performed with Sigma Stat software (version 2.0; Systat Software, San Jose, CA), and curve fits were performed with the software package SPSS. FCR and circumferential stress values were compared using two-factor ANOVA with repeated measures where group (VD vs. control) was one factor and pressure level (0–20 mmHg) or strain level was the second factor. Post hoc testing was performed with a Student-Neuman-Keul's test. For nonparametric data, Friedman repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks was performed with a Dunn's pair-wise comparison post hoc test.

Pharmacological data and quantification results from biological end points (i.e., immunohistochemistry, histology, and biochemical assays) for control and VD comparisons were evaluated using a Students t-test for parametric data and a Mann-Whitney rank sum test for nonparametric data. For all data, P values <0.5 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Functional Results

In the proximal urethra, change in OD in response to the 8-mmHg increase in static pressure was similar in both control (n = 8; 43.4 ± 6.5%) and VD (n = 9; 51.0 ± 4.6%) preparations (Table 1). NOSi did not elicit a significant response in either control (−0.2 ± 0.4%, where the minus sign indicates contraction, i.e., a decrease in OD) or VD (0.2 ± 1.6%) preparations. PE (40 μM) induced a contraction that was significantly larger in the VD proximal urethra (−11.2 ± 1.5%; P = 0.02) than in control proximal urethra (−5.9 ± 1.3%). However, five out of nine specimens were unable to maintain PE-induced maximal contraction (Fig. 1). During the PE-induced contraction, application of EDTA elicited an increase in OD that was smaller in VD (6.2 ± 1.5%) than in controls (9.8 ± 1.9%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.07; Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of distension and drug treatments on control and VD urethral OD

| Control (n =8) |

VD (n =9) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal | Middle | Distal | Proximal | Middle | Distal | |

| %OD8mmHG | 43.4 ± 6.5 | 29.4 ± 3.4* | 18.7 ± 2.7 | 51.0 ± 4.6 | 16.0 ± 1.9* | 20.8 ± 4.5 |

| %ODNOSi | −0.2 ± 0.4 | −0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 1.6 | −0.6 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| %ODPE | −5.9 ± 1.3† | −6.3 ± 1.0 | −4.2 ± 2.0 | −11.2 ± 1.5† | −3.6 ± 1.0 | −5.5 ± 1.9 |

| %ODEDTA | 9.8 ± 1.9 | 4.7 ± 0.7‡ | 14.1 ± 3.8 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 10.5 ± 2.1‡ | 11.0 ± 2.7 |

Values are means ± SE. Functional results [percent outer diamter (%OD) changes] for proximal, middle, and distal segments of control and vaginal distension (VD) urethral specimens. Effects are indicated for abrupt 8 mmHg of static pressure, nitric oxide synthase inhibitor (NOSi), phenylephrine (PE), and EDTA. Positive values (+) indicate an increase in OD value (i.e., relaxation), and negative values (−) indicate a decrease in OD value (i.e., contractions).

P < 0.05, significantly different change in OD in response to 8 mmHg of intraurethral pressure between control and VD middle urethral segments.

P < 0.05, significantly different change in OD in response to PE between control and VD proximal segments.

P < 0.05, significantly different change in OD response to EDTA between control and VD middle segments.

For middle urethral segments, the change in OD in response to an increase in pressure to 8 mmHg was significantly less for VD urethras (n = 9; 16.0 ± 1.9%) compared with controls (n = 8; 29.4 ± 3.4%; P = 0.005). While NOSi had minimal effects on control (−0.9 ± 0.7%) and VD (−0.6 ± 0.7%) middle segments, PE-induced contraction for VD middle segments (−3.6 ± 1.0%) was less than that of controls (−6.3 ± 1.0%), although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.08). EDTA-induced relaxation was significantly higher for the VD group (10.5 ± 2.1%) compared with the control response (4.7 ± 0.7%; P = 0.02; Table 1).

All responses in the distal urethral segments were unaffected by VD (Table 1). The response to an 8-mmHg increase of pressure was similar for both controls (n = 8; 18.7 ± 2.7%) and VD (n = 9; 20.8 ± 4.5%). Application of NOSi did not elicit significant changes in control (1.6 ± 0.4%) and VD (1.5 ± 0.7%) preparations. Additionally, the contractile responses to PE and relaxation responses to EDTA were not significantly different between control (−4.2 ± 2.0 and 14.1 ± 3.8%, respectively) and VD (−5.5 ± 1.9 and 11.0 ± 2.7%, respectively) distal segments.

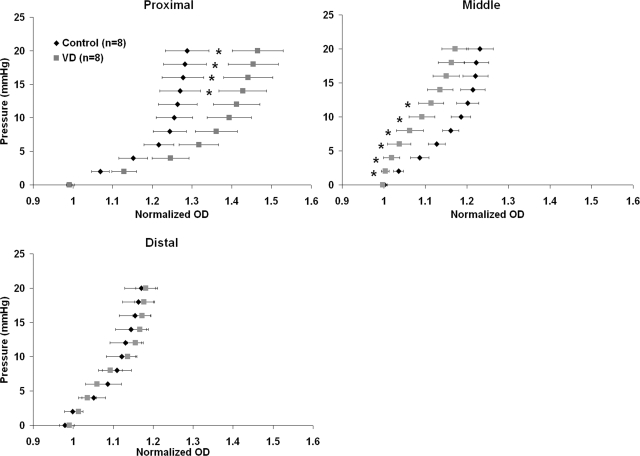

Biomechanical Results

General pressure-diameter behavior in the presence of PE.

Average pressure-diameter data revealed changes following VD in urethral active mechanical properties. For the proximal urethral segment, the VD (n = 8) pressure-diameter curve was shifted to the right of that of controls (n = 8; Fig. 2, top left), indicating a greater compliance (specifically for pressures ranging from 14 to 20 mmHg). Conversely, the pressure-diameter data for the middle urethral segment shifted to the left in VD compared with the control, significantly for pressures ranging from 2 to 12 mmHg (Fig. 2, top right). In the distal urethral preparations, there were no noticeable differences in the pressure-diameter curves between the VD and control groups (Fig. 2, bottom).

Fig. 2.

Pressure-diameter curves generated in the active state (after precontraction with PE) for the proximal (top, left), middle (top, right), and distal (bottom) segments in control and VD preparations. Error bars represent SE. Proximal control urethras were significantly stiffer in pressures ranging from 14 to 20 mmHg (indicated by *P < 0.05). Middle control urethras were significantly more compliant than VD middle segments from 2 to 12 mmHg (indicated by *P < 0.05).

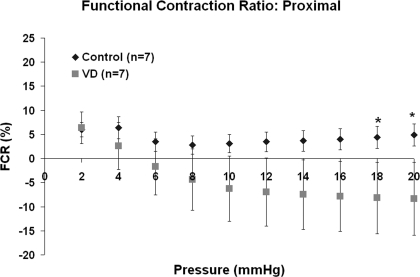

FCR in the presence of PE.

FCR values for control proximal segments indicated that the urethral smooth muscle activity reached its maximum at 4 mmHg (6.4 ± 2.3%). Control FCR values exhibited steady smooth muscle activity (∼5–7%) for pressures ranging up to 20 mmHg (Fig. 3). Conversely, smooth muscle activity in proximal segments of VD urethras accounted for 6.4 ± 3.3% of the activity at 2 mmHg but declined with each increase in static pressure, reaching negative FCR values by 6 mmHg. At 18- to 20-mmHg increments of pressure, smooth muscle activity in the proximal segments of VD urethras was significantly less (−8.2 ± 7.4%; note the minus sign indicating a lack of smooth muscle activity, e.g., only the passive matrix was playing a role in pressure-diameter response) compared with controls (5.0 ± 2.3%; P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Functional contraction ration (FCR) value for proximal segments for both control and VD urethras. *P < 0.05, significant difference between control and VD for the proximal FCR values at 18 and 20 mmHg. Error bars represent SE.

For middle urethral segments, FCR values indicated that contribution of smooth muscle activity did not significantly change after VD. Control middle segments had higher FCR values (ranging from 8.4 ± 5.9% minimum to 13.5 ± 5.3% maximum) than VD middle segments (ranging from 0.1 ± 2.4% minimum to 8.0 ± 1.2% maximum) over the entire pressure range; however, the average values of the two groups were not significantly different (P > 0.05). FCR values for distal segments indicated that VD did not alter the smooth muscle response to the adrenergic agonist.

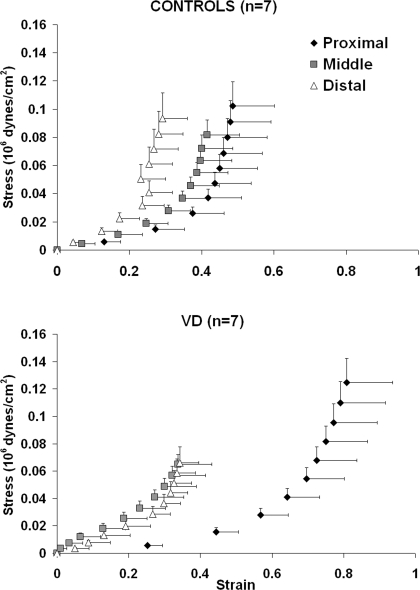

Circumferential stress-strain response in the presence of PE.

In proximal segments, VD shifted the circumferential stress-strain curve to the right of controls, indicating a decrease in stiffness (Fig. 4, top). The shape of the circumferential stress-strain curve was exponential in control middle urethral segments and was more sigmoidal in VD urethras, indicating that middle VD segments have more smooth muscle tone. The circumferential stress-strain response curves for distal urethras was unaffected by VD. All fits for determination of circumferential stress values (from low, middle, and high strain ranges) had values of R2 ≥ 0.987 ± 0.013.

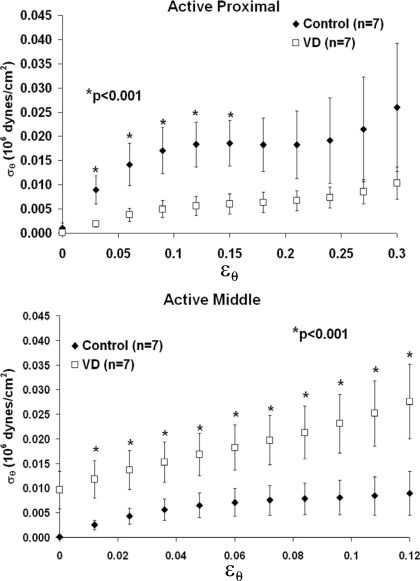

Fig. 4.

Active circumferential stress-strain response for control (top; n = 7), and VD (bottom; n = 7) urethras. Error bars represent SE.

At low strain ranges (0.03–0.12), circumferential stress values for VD proximal urethras (n = 7; Fig. 5, top) were significantly less (P < 0.001) than those of controls (n = 7). Circumferential stress values in VD preparations were reduced although not significantly at middle strain ranges and not changed at high strain values (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Active proximal and middle circumferential stress values for control and VD groups derived for low circumferential strains in proximal (top) and middle urethral segments. *P < 0.001, significance for comparisons between the control and VD groups at low strains ranging from 0.03 to 0.12 for proximal and the entire low strain range for middle segments. Error bars represent SE.

In the middle urethra, the VD group (n = 7) exhibited higher circumferential stress values compared with those of controls (n = 7; P < 0.001) across the entire low strain range from 0–0.12 (Fig. 5, bottom). At middle circumferential strain values, trends (not significant) indicated that the VD urethra maintained higher circumferential strain values. Conversely, at high strain ranges in VD preparations, circumferential stress values were decreased but not significantly.

Circumferential stress values of the distal urethral segment in the presence of an adrenergic agonist were not affected by VD.

Histological Results

PGP 9.5.

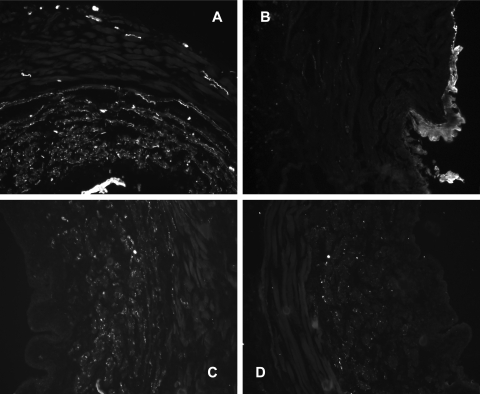

Positive staining for the PGP 9.5 antigen was present in urethral smooth muscle, as well as around the vasculature, throughout the striated muscle, and the urothelial layer in control urethras (Fig. 6). In VD urethras, staining was reduced or absent in the striated muscle, in the vasculature, and in the smooth muscle layer. The urothelial layer was thickened after VD, particularly in the proximal segment, but still exhibited abundance for staining against PGP 9.5 (Fig. 6, top). Quantification of the medial and adventitial layers of the urethra (i.e., exclusion of the urothelium) revealed significant reductions (P < 0.05) in the amount of staining for PGP 9.5 in the proximal, middle, and distal urethras of VD preparations (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Immunofluorescence staining in control (A and C) and VD (B and D) proximal urethras for PGP 9.5 (A and B) and tyrosine hydroxylase (C and D). Images are partial cross sections of the urethra acquired at ×20 magnification. Positive staining is indicated by white areas in the grayscale images. Quantitative measurements of the staining are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Differences in PGP 9.5 and TH staining in control and VD urethras

| Control (n = 7) |

VD (n = 7) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal | Middle | Distal | Proximal | Middle | Distal | |

| %PGP 9.5 | 6.3 ± 1.2a | 6.3 ± 1.1b | 4.5 ± 1.0c | 2.8 ± 0.7a | 2.8 ± 0.8b | 2.3 ± 0.4c |

| %TH | 2.1 ± 0.3d | 3.7 ± 0.7e | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.3d | 1.2 ± 0.3e | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

Values are means ± SE. Quantitative analysis of staining against protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5; general peripheral nerve marker) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH; sympathetic nerve marker) in proximal, middle, and distal segments of control (n = 7) and VD (n = 7) urethras. Measurements represent the area of staining as a percentage of the tissue cross-sectional area.

P < 0.05, significant difference in PGP 9.5-stained area between control and VD proximal segments.

P < 0.05, significant difference in PGP 9.5-stained area between control and VD middle segments.

P < 0.05, significant difference in PGP 9.5-stained area between control and VD distal segments.

P < 0.05, significant difference in TH-stained area between control and VD proximal segments.

P < 0.05, significant difference in PGP 9.5-stained area between control and VD middle segments.

TH.

In control urethras, positive staining against TH was prevalent throughout the medial layer of the proximal, middle, and distal segments where the smooth muscle is located. The urothelium did not exhibit staining. In VD urethras, the area stained for TH was reduced by 50% in the proximal segments and by 70% in the middle segments (Table 2; P < 0.05) but not changed in the distal segments (Fig. 6, bottom; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Impairment of sympathetic nerve activity is thought to be one of the factors contributing to urinary incontinence (26, 39). Urethral smooth muscle, which expresses α1-adrenergic receptors, is innervated by sympathetic adrenergic nerves. During urine storage, these nerves release norepinephrine, which acts on α1-adrenergic receptors in the smooth muscle to induce a urethral contraction and increase urethral outlet resistance (39). The biomechanical and functional experiments performed in this study suggest that this storage mechanism is damaged after VD.

Studies utilizing a VD model in rats or mice have revealed many changes to the urethra in vivo, consistent with birth trauma-induced stress urinary incontinence. It was shown that VD decreases leak point pressure (5, 17, 22) and decreases closure pressure in the middle urethra (17). Histological analyses showed that VD decreases the density of nerve fascicles (5, 21) and alters smooth and striated muscle structure (20, 36).

Previous studies in our laboratory (30) revealed a decrease in basal tone in the VD proximal urethra. In the present study, urethras were assessed functionally (under constant static pressure of 8 mmHg) and biomechanically (under increasing pressure from 0 to 20 mmHg) in the presence of a concentration of an α1-adrenergic receptor agonist, which produces a maximum contraction of urethral smooth muscle (12, 14). The proximal urethral contractile response to PE increased in VD preparations (Table 1). On the other hand, decreased FCR values (Fig. 3) and decreased circumferential stress values at low strains (Fig. 5) in VD proximal urethras suggest that there is reduced PE-induced muscle tone in the presence of increasing pressures (0–20 mmHg). In further support of this concept, it was observed that VD proximal segments were unable to maintain maximum PE-induced contraction in five out of nine VD specimens (Fig. 1). Thus it is possible that while the maximum PE response is initially larger in VD proximal segments, the smooth muscle may become desensitized or fatigue more rapidly during α1-adrenergic stimulation, similar to what occurs in rat aortic smooth muscle following sympathetic nerve damage (6). Denervation in the proximal urethral segment in VD preparations was evident by a decrease in staining for PGP 9.5 (a pan-neuronal marker), indicating a decrease in general nerve density in VD proximal urethras compared with continent controls. Additionally, staining for TH in the proximal urethra indicated a significant decrease in sympathetic adrenergic nerves (Fig. 6; Table 2). Our biomechanical evaluation of the urethral proximal segment indicated that VD had significantly weakened the muscular response to increasing incremental pressures, which concurs with the study by Kuo (19) who reported that urethral contractility induced by norepinephrine, a nonselective adrenergic agonist that activates α- and β-adrenergic receptors, was significantly decreased after VD. Clinical studies (25) of the urethra in stress urinary incontinence have cited an enlarged proximal urethra.

In the middle urethra, VD produced small changes in the PE-evoked responses that were not statistically significant (Table 1). The increase in OD response evoked by an increase in pressure to 8 mmHg was significantly decreased in VD compared with control urethras. This may be due to an increase in basal muscle tone in the middle segment after VD. This was further supported by an increase in EDTA-induced relaxation in VD urethras, which is a measure of basal tone present at the initial static 8 mmHg, as well as by our previous studies (30) in which basal pressure-diameter data revealed an increased biomechanical stiffness in VD urethras. Additionally, the pressure-diameter curves exhibited an increased stiffness after VD for the middle segment in the presence of PE (note that the VD curve is shifted to the left of the control curve in Fig. 2). The VD middle segment also exhibited significantly increased circumferential stress compared with controls, specifically at low strain levels (Fig. 5, bottom). Therefore, PE-induced contractions from the VD middle urethra may have been masked by an increased presence of basal tone. Additionally, VD middle urethras exhibited higher stiffness and circumferential stress compared with control urethras in the presence of PE.

After VD, the increase in middle urethral circumferential stress and lack of compliance in the presence of PE could be due to adaptive postsynaptic supersensitivity induced by an abrupt interruption of excitatory neurotransmission (i.e., post- or preganglionic nerve damage during VD; Refs. 9, 13), leading to an enhanced response to the adrenergic receptor agonist. The lack of staining against PGP 9.5 in the middle urethral segment, indicating a remarkable loss of nerve fibers in this segment after VD, is consistent with the idea of denervation supersensitivity in the middle urethral smooth muscle. Moreover, there was a lack of staining for TH, indicating adrenergic nerve damage (Fig. 6; Table 2), which was similar to the findings of a previous study (35) in the bladder neck/proximal urethra after simulated birth trauma in rats. This phenomenon of smooth muscle supersensitivity has also been demonstrated by functional and biomechanical changes in denervated arteries of the middle ear (23), guinea pig vas deferens (13), and denervated segments of the rat jejunum (3).

In the distal urethra, staining for PGP 9.5 was reduced but staining for TH was not changed, suggesting that VD has a minimal effect on adrenergic function of the distal urethra compared with the proximal and middle portions of the urethra. In addition, no changes in functional and biomechanical measures were detected in the distal segments.

The histological demonstration of urethral denervation after VD shown here should be confirmed in future functional experiments by examining the changes in urethral responses to neural stimulation. Damage to sympathetic nerves is an important issue because it would reduce the sympathetic neural control of the urethral smooth muscle and, in turn, reduce the urethral outlet resistance and bladder leak point pressure in vivo. On the other hand, damage to parasympathetic nitric oxidergic nerves would interfere with urethral relaxation mechanisms.

Although this study's main focus is on the effects of VD on urethral smooth muscle and innervation, VD-induced alterations in collagen and elastin could contribute to urethral smooth muscle dysfunction in proximal and middle segments. Before this study, we assessed passive urethral changes in biomechanics post-VD (30), where only extracellular matrix and inactive musculature contribute to measurements. Results indicated that VD caused a significant increase in proximal urethral compliance. In women with SUI, peri-urethral tissue exhibits fragmented elastic fibers (11) and altered organization and content of collagen (7). Furthermore, Rocha et al. (32) reported that VD-induced birth trauma increased both collagen and elastin in the middle urethra.

In normal female rat urethras utilizing the same ex vivo testing methods, it appeared that the activation of both smooth and striated muscles in the middle urethral segment with PE and acetylcholine, respectively, was necessary to provide optimal urethral resistance at pressures ranging from 0 to 10 mmHg (37). Combined activation of smooth and striated muscles also produces higher circumferential stress values than activation of smooth muscle alone (14). In vivo studies (16) also showed that sympathetic nerve activation of urethral smooth muscle significantly contributes to urethral continence mechanisms, especially those induced by bladder-to-urethral reflexes during passive intravesical pressure increases in rats. The results of the present in vitro study indicate that VD produces significant changes in smooth muscle function in the proximal and middle urethra that very likely contribute to the dysfunction in urethral continence mechanisms that have been detected in rat SUI models in vivo.

In summary, VD causes the following: 1) increased adrenergic contraction in the proximal segment; 2) decreased functional contraction ratio and circumferential stress in the proximal segment; 3) increased basal tone in the middle urethral segment; 4) increased circumferential stress in the middle segment in the presence of PE; and 5) a marked reduction in nerve density in all three segments, particularly a loss of sympathetic adrenergic nerves in the proximal and middle urethral segments. These findings support the view that smooth muscle and nerve changes may be factors contributing to a defective urine storage mechanism after birth trauma. However, more mechanistic studies, involving an analysis of neurally evoked responses, must be performed to identify the factors contributing to the disruption of sympathetic neural control of the urethra after VD.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering Grants T32-EB-001026 and F31-EB-004738-01 and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01-DK-67226.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vickie Erickson for immunhistochemical expertise; Robert Dulabon, Dr. Aura Negoita, Donna Haworth, and Timothy Ungerer for technical support; and Bill Hughes for the high quality work of the machine shop.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders K. Recent developments in stress urinary incontinence in women. Nurs Stand 20: 48–54, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagot K, Chess-Williams R. Alpha(1A/L)-adrenoceptors mediate contraction of the circular smooth muscle of the pig urethra. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol 26: 345–353, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balsiger BM, He CL, Zyromski NJ, Sarr MG. Neuronal adrenergic and muscular cholinergic contractile hypersensitivity in canine jejunum after extrinsic denervation. J Gastrointest Surg 7: 572–582, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon TW, Wojcik EM, Ferguson CL, Saraga S, Thomas C, Damaser MS. Effects of vaginal distension on urethral anatomy and function. BJU Int 90: 403–407, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damaser MS, Broxton-King C, Ferguson C, Kim FJ, Kerns JM. Functional and neuroanatomical effects of vaginal distention and pudendal nerve crush in the female rat. J Urol 170: 1027–1031, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Mas MM, Abdel-Galil AG, el-Gowelli HM, Daabees TT. Short-term aortic barodenervation diminishes alpha 1-adrenoceptor reactivity in rat aortic smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol 322: 201–210, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falconer C, Blomgren B, Johansson O, Ulmsten U, Malmstrom A, Westergren-Thorsson G, Ekman-Ordeberg G. Different organization of collagen fibrils in stress-incontinent women of fertile age. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 77: 87–94, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falconer C, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Blomgren B, Johansson O, Ulmsten U, Westergren-Thorsson G, Malmstrom A. Paraurethral connective tissue in stress-incontinent women after menopause. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 77: 95–100, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming WW. Cellular adaptation: journey from smooth muscle cells to neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291: 925–931, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fridez P, Makino A, Miyazaki H, Meister JJ, Hayashi K, Stergiopulos N. Short-Term biomechanical adaptation of the rat carotid to acute hypertension: contribution of smooth muscle. Ann Biomed Eng 29: 26–34, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goepel C, Thomssen C. Changes in the extracellular matrix in periurethral tissue of women with stress urinary incontinence. Acta Histochem 108: 441–445, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassouna M, Abdel-Hakim A, Abdel-Rahman M, Galeano C, Elhilali MM. Response of the urethral smooth muscles to pharmacological agents. I. Cholinergic and adrenergic agonists and antagonists. J Urol 129: 1262–1264, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hershman KM, Taylor DA, Fleming WW. Adaptive supersensitivity and the Na+/K+ pump in the guinea pig vas deferens: time course of the decline in the alpha 2 subunit. Mol Pharmacol 47: 726–729, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jankowski RJ, Prantil RL, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Huard J, Vorp DA. Biomechanical characterization of the urethral musculature. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1127–F1134, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jankowski RJ, Prantil RL, Fraser MO, Chancellor MB, De Groat WC, Huard J, Vorp DA. Development of an experimental system for the study of urethral biomechanical function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F225–F232, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamo I, Cannon TW, Conway DA, Torimoto K, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. The role of bladder-to-urethral reflexes in urinary continence mechanisms in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F434–F441, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamo I, Kaiho Y, Canon TW, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Prantil RL, Vorp DA, Yoshimura N. Functional analysis of active urethral closure mechanisms under sneeze induced stress condition in a rat model of birth trauma. J Urol 176: 2711–2715, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi K. Role of catecholamine signaling in brain and nervous system functions: new insights from mouse molecular genetic study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 6: 115–121, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo HC. Effects of vaginal trauma and oophorectomy on the continence mechanism in rats. Urol Int 69: 36–41, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin AS, Carrier S, Morgan DM, Lue TF. Effect of simulated birth trauma on the urinary continence mechanism in the rat. Urology 52: 143–151, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin YH, Liu G, Daneshgari F. A mouse model of simulated birth trauma induced stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 27: 353–358, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin YH, Liu G, Li M, Xiao N, Daneshgari F. Recovery of continence function following simulated birth trauma involves repair of muscle and nerves in the urethra in the female mouse. Eur Urol 57: 506–512, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangiarua EI, Joyce EH, Bevan RD. Denervation increases myogenic tone in a resistance artery in the growing rabbit ear. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 250: H889–H891, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayo ME, Hinman F. The effect of urethral lengthening. Br J Urol 45: 621–630, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGuire EJ. Pathophysiology of stress urinary incontinence. Rev Urol 6, Suppl 5: S11–17, 2004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller KL. Stress urinary incontinence in women: review and update on neurological control. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 14: 595–608, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreland RB, Brioni JD, Sullivan JP. Emerging pharmacologic approaches for the treatment of lower urinary tract disorders. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 308: 797–804, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nygaard I, Thom DH, Calhoun EA. Urinary incontinence in women [online]. In: Urologic Diseases in America, edited by Litwin MS, Saigal CS. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/statistics/uda/index.htm [2007] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pagani M, Mirsky I, Baig H, Manders WT, Kerkhof P, Vatner SF. Effects of age on aortic pressure-diameter and elastic stiffness-stress relationships in unanesthetized sheep. Circ Res 44: 420–429, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prantil RL, Jankowski RJ, Kaiho Y, de Groat WC, Chancellor MB, Yoshimura N, Vorp DA. Ex vivo biomechanical properties of the female urethra in a rat model of birth trauma. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1229–F1237, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resplande J, Gholami SS, Graziottin TM, Rogers R, Lin CS, Leng W, Lue TF. Long-term effect of ovariectomy and simulated birth trauma on the lower urinary tract of female rats. J Urol 168: 323–330, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha MA, Sartori MG, De Jesus Simoes M, Herrmann V, Baracat EC, Rodrigues de Lima G, Girao MJ. The impact of pregnancy and childbirth in the urethra of female rats. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 18: 645–651, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rocha MA, Sartori MG, De Jesus Simoes M, Herrmann V, Baracat EC, Rodrigues de Lima G, Girao MJ. Impact of pregnancy and childbirth on female rats' urethral nerve fibers. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 18: 1453–1458, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuessler B, Baessler K. Pharmacologic treatment of stress urinary incontinence: expectations for outcome. Urology 62: 31–38, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sievert KD, Bakircioglu ME, Tsai T, Nunes L, Lue TF. The effect of labor and/or ovariectomy on rodent continence mechanism–the neuronal changes. World J Urol 22: 244–250, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sievert KD, Emre Bakircioglu M, Tsai T, Dahms SE, Nunes L, Lue TF. The effect of simulated birth trauma and/or ovariectomy on rodent continence mechanism. Part I: functional and structural change. J Urol 166: 311–317, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Streng T, Santti R, Talo A. Similarities and differences in female and male rat voiding. Neurourol Urodyn 21: 136–141, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teramoto N, McMurray G, Brading AF. Effects of levcromakalim and nucleoside diphosphates on glibenclamide-sensitive K+ channels in pig urethral myocytes. Br J Pharmacol 120: 1229–1240, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thor KB, Donatucci C. Central nervous system control of the lower urinary tract: new pharmacological approaches to stress urinary incontinence in women. J Urol 172: 27–33, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werkstrom V, Ny L, Persson K, Andersson KE. Neurotransmitter release evoked by alpha-latrotoxin in the smooth muscle of the female pig urethra. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 356: 151–158, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]