Abstract

Stem cells are critical in maintaining adult homeostasis and have been proposed to be the origin of many solid tumors, including pancreatic cancer. Here we demonstrate the expression patterns of the putative intestinal stem cell marker DCAMKL-1 in the pancreas of uninjured C57BL/6 mice compared with other pancreatic stem/progenitor cell markers. We then determined the viability of isolated pancreatic stem/progenitor cells in isotransplantation assays following DCAMKL-1 antibody-based cell sorting. Sorted cells were grown in suspension culture and injected into the flanks of athymic nude mice. Here we report that DCAMKL-1 is expressed in the main pancreatic duct epithelia and islets, but not within acinar cells. Coexpression was observed with somatostatin, NGN3, and nestin, but not glucagon or insulin. Isolated DCAMKL-1+ cells formed spheroids in suspension culture and induced nodule formation in isotransplantation assays. Analysis of nodules demonstrated markers of early pancreatic development (PDX-1), glandular epithelium (cytokeratin-14 and Ep-CAM), and isletlike structures (somatostatin and secretin). These data taken together suggest that DCAMKL-1 is a novel putative stem/progenitor marker, can be used to isolate normal pancreatic stem/progenitors, and potentially regenerates pancreatic tissues. This may represent a novel tool for regenerative medicine and a target for anti-stem cell-based therapeutics in pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: stem/progenitor cell marker, DCAMKL-1, pancreas, neurogenin 3, nestin

characterization of stem cells from the hematopoietic and central nervous system has emphasized the importance of specific cell surface antigens that permit the isolation of stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (17, 29). A candidate pancreatic stem cell, characterized by expression of the neural stem cell marker nestin and lack of established islet and ductal cell markers, has been described (1, 12, 32). Furthermore, the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor neurogenin 3 (NGN3) controls endocrine cell fate specification in uncommitted pancreatic progenitor cells. In the pancreas, NGN3+ cells coexpress neither insulin nor glucagon, suggesting that NGN3 marks early precursors of pancreatic endocrine cells. Moreover, NGN3-deficient mice do not develop islet cells and are diabetic. These data taken together suggest that NGN3 and nestin are critical components of the pancreatic stem/progenitor cell compartment. A recent study demonstrated that expansion of the β-cell mass following pancreatic duct ligation resulted in ductal NGN3 gene expression and the ensuing differentiation of endogenous progenitor cells (31).

We have recently determined that doublecortin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase-like-1 (DCAMKL-1), a microtubule-associated kinase expressed in postmitotic neurons, is a putative intestinal stem cell marker (14, 15). Here we report that DCAMKL-1 is also expressed in pancreatic islet epithelial cells with a distribution similar to the putative pancreatic stem/progenitor cell markers NGN3 and nestin. Furthermore, following DCAMKL-1-based FACS, isolated cells formed spheroidlike structures in suspension culture. When injected subcutaneously into flanks of nude mice, nodules formed and contained cells expressing markers of early pancreatic development (PDX-1), glandular epithelium [cytokeratin-14 and epithelial cell adhesion molecule (Ep-CAM)], and islets (somatostatin and secretin). These data taken together identify DCAMKL-1 as a novel pancreatic ductal and islet stem/progenitor cell marker.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

Six- to 8-wk-old C57BL/6 (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) athymic nude mice (NCr-nu) (NCI-Frederick, Frederick, MD) were used for the experiments. Mice were housed under controlled conditions, including a 12-h light-dark cycle, with ad libitum access to diet and water. All animal experiments were performed according to the animal protocols approved by the University Animal Study Committee.

Immunohistochemistry.

Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections by utilizing a pressurized decloaking chamber (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 99°C for 18 min.

For brightfield microscopy, slides were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide, then in normal serum and BSA at room temperature for 20 min. After incubation with primary antibody [DCAMKL-1 1:100 (rabbit), PDX-1 1:1,000 (rabbit), Ep-CAM 1:100 (rabbit) glucagon 1:100 (goat) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); Ki67 1:300 (rabbit) (Thermo Scientific/Lab Vision, Fremont, CA); NGN3 1:200 (goat), nestin 1:100 (rabbit) (Abgent, San Diego, CA); insulin 1:250 (goat), somatostatin 1:250 (goat), cytokeratin-14 1:100 (rabbit), and secretin 1:100 (goat) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA)], the slides were incubated either in polymer-horseradish peroxidase secondary (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for rabbit-derived or goat polymer detection kit (Biocare Medical) for goat-derived antibodies as appropriate. Slides were developed with diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Tyramine signal amplification for NGN3 in adult mouse tissues was performed per manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

For fluorescence microscopy, slides were first incubated in Image-iT FX signal enhancer (Invitrogen), followed by normal serum and BSA at room temperature for 20 min. After incubation with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, slides were incubated in appropriate donkey anti-goat/rabbit Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary as appropriate [488 (green) and 568 (red) (Invitrogen)].

Microscopic examination.

Slides were examined by utilizing the Nikon 80i microscope and DXM1200C camera for brightfield microscopy. Fluorescent images were taken with PlanFluoro objectives, utilizing CoolSnap ES2 camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Images were captured with NIS-Elements software (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY).

Real-time reverse transcription-PCR analyses.

Total RNA isolated from FACS sorted pancreatic cells was subjected to reverse transcription with Superscript II RNase H-reverse transcriptase and random hexanucleotide primers (Invitrogen). The cDNA was subsequently used to perform real-time PCR by SYBR chemistry (SYBR Green I; Molecular Probes) for specific transcripts using gene specific primers and Jumpstart Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The crossing threshold value assessed by real-time PCR was noted for the transcripts and normalized with β-actin mRNA. The changes in mRNA were expressed as fold change relative to control with ±SE value.

Primers used are as follows. β-actin: forward 5′-GGTGATCCACATCTGCTGGAA-3′, reverse 5′-ATCATTGCTCCTCCTCAGGG-3′; DCAMKL-1: forward 5′-CAGCCTGGACGAGCTGGTGG-3′, reverse 5′-TGACCAGTTGGGGTTCACAT-3′; NGN3: forward 5′-CGCACCATGGCGCCTCATCCCTTGG-3′, reverse 5′-CAGAGGATCCTCTTCACAAGAAGTCT-3′; nestin: forward 5′-CACCTCAAGATGTCCCT-3′, reverse 5′-GCAGCTTCAGCTTGGGGTC-3′; somatostatin: forward 5′-GGACCCCAGACTCCGTCAGT-3′, reverse 5′-GGGCTCGGACAGCAGCTCTG-3′; insulin: forward 5′-CCCAGCCCTTAGTGACCAGC-3′, reverse 5′-TTTATTCATTGCAGAGGGGT-3′; glucagon: forward 5′-GGCTGGATTGCTTATAATGC-3′, reverse 5′-ATCTCATCAGGGTCCTCATG-3′; CD133: forward 5′-GGCTATGACAAGGATGCC-3′, reverse 5′-GATCATCAATATCCAGCA-3′.

Stem/progenitor cell isolation from mouse pancreas.

We isolated and propagated DCAMKL-1+ stem/progenitor cells from mouse pancreas according to the procedures developed in neural (23–25) and breast stem cell biology (5). The pancreas and associated duct were rapidly dissected and perfused with 3 ml of cold HBSS containing 1 mg/ml collagenase XI (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mg/ml BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). The pancreatic tissues were minced and incubated in HBSS for 13 min at 37°C. Digestion was arrested with cold HBSS (Cellgro-Mediatech, Manasses, VA) containing 10% serum. The solution was shaken by hand for 1 min, washed three times with serum-free HBSS, and filtered through 400-μm mesh (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA). The cells obtained (flow through) were incubated with trypsin (Cellgro) at 37°C, pipetted to create a single cell suspension and subjected to FACS based on cell surface expression of DCAMKL-1.

FACS sorting.

The single cell suspension was incubated with 1:100 dilution of Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated DCAMKL-1 antibody targeting the COOH-terminal extracellular domain for 25 min and washed twice with HBSS containing 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were sorted with Influx-V cell sorter (Cytopeia/BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and collected cells were grown in tissue culture media: DMEM (Cellgro) containing EGF (25 ng/ml), basic FGF (20 ng/ml), and insulin (5 ng/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) without serum on nontreated or ultralow adherent plates (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in a suspension culture.

Isotransplantation assay.

Collected cells expressing DCAMKL-1 were allowed to form spheroids in suspension culture for 21 days. Spheroids were disassociated, suspended in Matrigel, and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of athymic nude mice (NCr-nu) (NCI-Frederick) housed in specific pathogen-free conditions. Animals were killed, and nodules were excised, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis.

RESULTS

Pancreatic DCAMKL-1 expression.

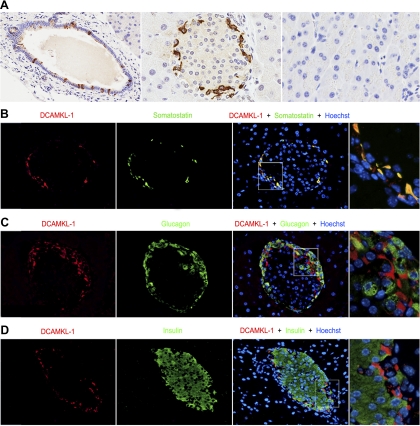

DCAMKL-1 is expressed in the main pancreatic duct (Fig. 1A, left) and on the periphery of pancreatic islets (Fig. 1A, middle). There was no detectable DCAMKL-1 expression within the acinar cells of uninjured adult mice (Fig. 1A, right). To determine the specific islet cell subtype, we evaluated for coexpression of the endocrine markers somatostatin (δ-cell), glucagon (α-cell), and insulin (β-cell). We found that both DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 1B, left) and somatostatin (Fig. 1B, second from left) were expressed in the islet periphery. Merged images revealed costaining of DCAMKL-1 with somatostatin (Fig. 1B, third and fourth from left). Glucagon was also found in the periphery of the islet (Fig. 1C, second from left) but did not colocalize with DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 1C, third and fourth from left). Insulin-expressing cells were observed throughout the islet (Fig. 1D, second from left) but we did not observe any coimmunostaining with DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 1D, third and fourth from left). Thus DCAMKL-1 expressing cells do not express the two major endocrine cell markers (insulin and glucagon) but do colocalize with somatostatin-expressing cells.

Fig. 1.

Pancreatic DCAMKL-1 expression in adult mice. A: DCAMKL-1 expression (brown) in the main pancreatic duct (left) (×200) and in the periphery of pancreatic islets (middle) (×400). No DCAMKL-1 expression is observed in acinar cells or accessory ducts (right) (×400). B: immunofluorescence demonstrating DCAMKL-1 (red) and somatostatin (green) staining of pancreatic islets. Colocalization is demonstrated in merged image. C: DCAMKL-1 (red) and glucagon (green) immunofluorescence staining of pancreatic islets. No colocalization is demonstrated in merged image. D: immunofluorescence demonstrating DCAMKL-1 (red) and insulin (green) staining of pancreatic islets. No colocalization is observed in merged image. Images on the far right in B–D are the magnified portion of the corresponding merged images. In the immunofluorescence staining, nuclei are stained blue with Hoechst dye.

Pancreatic stem/progenitor cell markers.

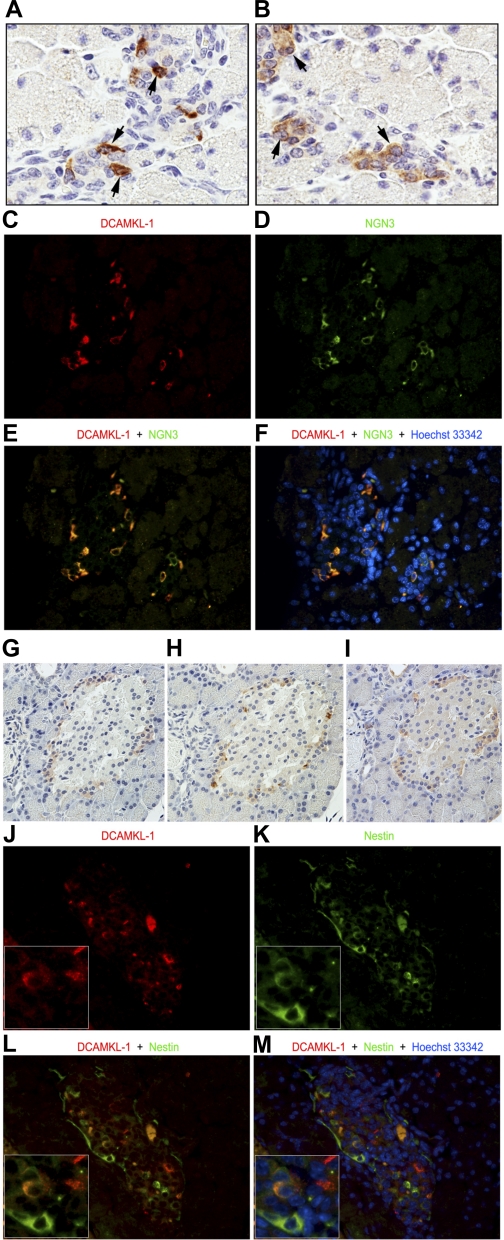

The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor NGN3 controls endocrine cell fate specification. All the major islet cell types, including insulin-producing β-cells, are derived from NGN3-positive endocrine progenitor cells (10). It is well known that NGN3 protein expression diminishes as mice reach adulthood (9, 21). We employed immunohistochemical analysis to determine the cell-specific expression patterns of DCAMKL-1 in newborn mice and with reference to NGN3 expression (8). We observed distinct expression of DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 2A) and NGN3 (Fig. 2B) in early islet formations. Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the presence of DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 2C) and NGN3 (Fig. 2D), with merged images revealing distinct colocalization within these developing tissues (Fig. 2, E and F).

Fig. 2.

DCAMKL-1 and other putative pancreatic stem/progenitor cell markers. Newborn mice pancreas demonstrates DCAMKL-1 staining (A; arrows) and neurogenin 3 (NGN3; B; arrows) (×600). Immunofluorescence staining for DCAMKL-1 (C; red) and NGN3 (D; green) in the newborn mice pancreas. E–F: colocalization demonstrated in merged image with nuclei stained blue with Hoechst dye (×400). Adult mouse pancreatic tissue serial sections stained with DCAMKL-1 (G), NGN3 (H), and nestin (I) (×200). Immunofluorescence staining of newborn mouse pancreas demonstrated the presence of DCAMKL-1 (J) and nestin (K). L–M: colocalization demonstrated in merged image with nuclei stained blue with Hoechst dye (×400). Insets in J–M are magnified images.

To confirm these findings in adult uninjured mice, we employed immunohistochemical staining on serial tissue sections. We observed common immunolocalized staining for DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 2G), NGN3 (Fig. 2H), and the pancreatic stem/progenitor cell marker candidate nestin (Fig. 2I) in all three sections. Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining of newborn mouse pancreas demonstrated the presence of DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 2J) and nestin (Fig. 2K), with merged images revealing colocalization within a few cells (Fig. 2, L and M). These data suggest that DCAMKL-1 marks pancreatic islet stem/progenitor cells, based on positional evidence, and coexpression with established markers of pancreatic stem/progenitor cells.

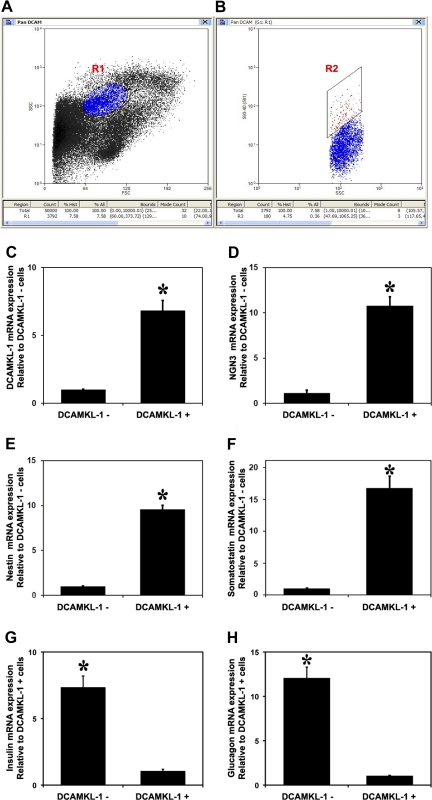

Isolation and propagation of pancreatic stem/progenitor cells.

Stem cells within a tissue are capable of self-renewal and differentiation. Dontu et al. (5) isolated human mammary stem/progenitor cells from normal breast tissues. When grown in ultralow attachment plates, they formed spheroid structures termed “mammospheres.” To test the hypothesis that there is a small subpopulation of distinct stem/progenitor cells within a normal uninjured rodent pancreas; we digested the mouse pancreas with ultrapure collagenase XI and performed FACS-based cell sorting for DCAMKL-1. On average, we sorted ∼0.4% of total cells using this method (Fig. 3, A and B). To characterize the phenotype of the sorted populations, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analyses of total RNA isolated from the DCAMKL-1+ and DCAMKL-1− cells. DCAMKL-1+ population demonstrated markedly increased (∼10-fold) expression of DCAMKL-1 (Fig. 3C), NGN3 (Fig. 3D), nestin (Fig. 3E), and somatostatin (Fig. 3F) compared with DCAMKL-1− cells. We observed a 7-fold increase in insulin (Fig. 3G) and 12-fold increase in glucagon (Fig. 3H) within the DCAMKL-1− cells compared with DCAMKL-1+ cells. We did not detect CD133 in DCAMKL-1+ cells but were able to detect significant CD133 expression in DCAMKL-1− cells (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

FACS-based isolation of DCAMKL-1 cells from mouse pancreas. FACS plots of sorted cells. A: side scatter oval gate R1. B: polygon gate R2 represents sorted fluorescent cells (red) from gate R1 (0.36% of total cells). The graphs represent the mRNA expression levels of DCAMKL-1 (C), NGN3 (D), nestin (E), somatostatin (F), insulin (G), and glucagon (H) in DCAMKL-1+ and DCAMKL-1− sorted cells. *P < 0.01.

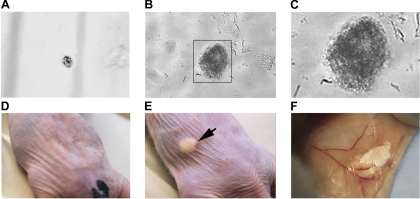

Three weeks after sorting, the formation of spheroids was observed in growth factor-supplemented serum-free media (5) (Fig. 4, A = days 0 and 4, B and C = day 21). Spheroids were separated, suspended in Matrigel, and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of athymic nude mice. After 4 wk we noted nodular growth at the site of DCAMKL-1 spheroid injection (Fig. 4E) compared with no growth in the Matrigel-alone-injected control (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, we noted tan-gray soft tissue outgrowth that extended beyond the original injection site, which appeared to show new blood vessel formation (Fig. 4F). We performed a total of 10 injections of pancreatic spheroids containing 50–100 cells each [into right and left flanks of nude mice (n = 5)]. After 4 wk, we observed growth in three of five nude mice for a total of six nodular growths. As a control, we performed spheroid formation assays for DCAMKL-1− cells. We did not observe spheroid formation in culture, even after 12 wk.

Fig. 4.

DCAMKL-1 sorted cells demonstrate growth in vitro and in vivo. FACS isolated DCAMKL-1+ cells in suspension culture at day 1 (A) and demonstrates spheroid formation at day 21 (B) (×400). C: magnified portion of image B. Athymic nude mice 4 wk after subcutaneous injection with either Matrigel alone (D) or spheroid with Matrigel (E); arrow indicates nodular growth. F: image demonstrates a tan-gray soft tissue outgrowth with blood vessel formation under the skin of the DCAMKL-1 spheroid-injected mouse.

DCAMKL-1-sorted spheroids induce pancreatic epithelial expression in the flanks of nude mice.

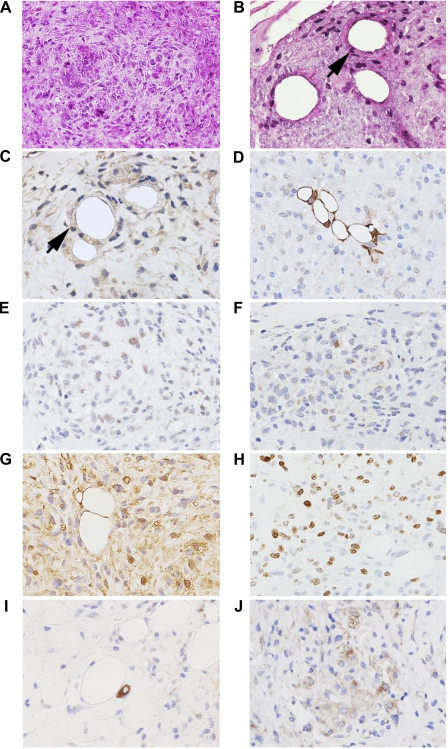

Histological analysis of the excised nodules revealed single cells with oval nuclei and large nucleoli, which appeared to be epithelial in nature, as well as isletlike structures (Fig. 5A) and ductlike formations (Fig. 5B). The glandular epithelial origin of these cells was confirmed by cytokeratin-14 immunoreactivity (Fig. 5C) (16, 19) and PDX-1, a marker of early pancreatic development (Fig. 5D). Additionally, many of the cells within the islet structures expressed somatostatin (Fig. 5E) and secretin (Fig. 5F) (18). Some of the cells were also positive for Ep-CAM, a marker of cells of epithelial origin (Fig. 5G) (3). Many cells were positive for Ki67, indicating an active proliferating status (Fig. 5H) (2). Furthermore, we observed cells that continued to express DCAMKL-1 in both the ductlike formations (Fig. 5I) and isletlike structures (Fig. 5J). These data taken together strongly suggest that DCAMKL-1-expressing cells isolated from the pancreas of normal uninjured mice by FACS and utilized in isotransplantation assays are in fact stem/progenitor cells.

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of nodular growth from spheroid injection. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of cells that appeared to be epithelial in nature and formed early isletlike structures (A) and cells that lined up around central spaces, which appeared to be poorly formed glands (B), as indicated by arrows. Cells around the central spaces were positive for glandular epithelial marker cytokeratin-14 (C) and PDX-1 (D), a marker of early pancreatic development. The early islet formations expressed endocrine markers somatostatin (E) and secretin (F). Additionally, cells within these nodules expressed the epithelial marker Ep-CAM (G), proliferation marker Ki67 (H) and DCAMKL-1 (I–J). Positive staining demonstrated by brown coloration (diaminobenzidine); all images shown at ×200 magnification.

DISCUSSION

Purification of stem and progenitor cells from an organ is increasingly becoming the gold standard experimental method to determine the mechanisms that regulate organ development and regeneration following injury. Establishment of such method of isolation of pancreatic stem/progenitor cells has been difficult because of the lack of definitive cell surface markers that reliably mark these relatively rare cell types. Identification of cancer stem or cancer initiating cells, however, has been much more successful as demonstrated by FACS-based sorting protocols by using a combination of cell surface markers followed by recapitulation of tumors in xenotransplantation assays (4, 5, 30). Similar studies using normal rodent or normal human pancreas have not yet been reported. Identification, isolation, and characterization of pancreatic stem/progenitor cells will permit genetic, biological, and developmental studies of pancreas during normal homeostasis and in response to inflammatory diseases and cancer.

In the pancreas, NGN3-positive cells coexpress neither insulin nor glucagon, suggesting that NGN3 marks early precursors of pancreatic endocrine cells. Pancreatic islet cells, including insulin-producing β-cells, are thought to arise from pancreatic endocrine progenitors expressing the transcription factor NGN3 (8, 13, 20). Moreover, NGN3-deficient mice do not develop any islet cells and are diabetic. Thus NGN-3 is a critical component of the pancreatic stem/progenitor cell compartment, at least with respect to endocrine fate determination. A recent convincing study demonstrated that the adult mouse pancreas contains islet cell progenitors and that expansion of the β-cell mass following injury induced by ligation of the pancreatic duct resulted in ductal NGN3 gene expression and differentiation of endogenous progenitor cells in a cell-autonomous, fusion-independent manner (31). These data suggest that functional islet progenitor cells can be induced in pancreatic ducts following injury. These data lend support to the notion that the main pancreatic duct may possess rare stem/progenitor cells that at least give rise to endocrine lineages. In our study, we have demonstrated that the putative intestinal stem cell marker DCAMKL-1 colocalizes with NGN3 and nestin in the normal uninjured mouse pancreas.

One major difficulty in this study is assessing immunoreactive NGN3 within adult mice. NGN3 protein is expressed abundantly in the developing mouse pancreatic endocrine progenitor cells and then dramatically reduced before terminal differentiation. Moreover, NGN3 is not a cell surface-expressing protein, thereby precluding NGN3-based FACS. We have demonstrated earlier that DCAMKL-1 is a cell surface protein and can be used to isolate mouse intestinal stem cells (15, 28). We utilized a similar strategy in this study to isolate pancreatic stem/progenitor cells.

Although originally considered to be a cytoplasmic protein (7), analysis of the DCAMKL-1 protein using the TMPred program (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) suggested that amino acids 534–560 represent a transmembrane domain, and amino acids 561–729 are outside the cell. Furthermore, it has been reported that DCAMKL-1 is expressed in adult brain with two transmembrane domains (amino acids 534–559 and 568–585), which strongly supports the suggestion that it is a cell surface-expressing protein with both intra- and extracellular domains (11, 27). We previously demonstrated cell surface DCAMKL-1 expression using the Pierce Cell Surface Protein Isolation Kit followed by Western blot for DCAMKL-1 (15). Subsequently, we generated an Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-DCAMKL-1 antibody (28), which targets the putative extracellular COOH-terminal epitope. In our experiments, stem/progenitor cells isolated from normal mouse pancreas formed spheroids in suspension culture. Furthermore, 50–100 cells isolated from a particular spheroid in vitro formed early epithelial and isletlike structures in nude mice and expressed markers of early pancreatic development. We are fully aware, however, that in our isograft model we do not have evidence of acinar cell development and we do not have three-dimensional evidence of a regenerated pancreas. We predict that the flank injection may not provide the optimal niche signals required for normal pancreatic regeneration. However, optimal in vitro three-dimensional culture systems are under development that may potentially overcome these obstacles. Nevertheless, we are encouraged by the vascularization observed within the isograft nodules, which may suggest a potential role for DCAMKL-1 signaling in growth augmentation. Thus the studies presented suggest that DCAMKL-1, a novel putative stem cell marker expressed primarily in quiescent cells of the gut (7, 14, 15), also marks normal pancreatic stem/progenitor cells.

Identification of stem/progenitor cells using a single marker represents a major advancement over many of the typical cell surface markers that generally have to be used in combination and as such represent markers of purification. Although recent studies using cell surface markers to isolate cancer stem cells from tumors have been described (24), similar studies have not been performed utilizing normal tissues. These studies have broad potential applications in regenerative medicine. Isolation and purification protocols in vitro or in vivo could be employed to replace insulin in diabetic patients as an example. Overall, these studies represent a major step toward understanding pancreatic biology under normal conditions. Further studies are underway in our laboratory to determine whether DCAMKL-1 is expressed in pancreatic cancer.

In conclusion, there has been considerable debate on the origin of the pancreatic stem cell. Several transgenic mouse models and injury models have suggested that ductal, islet and acinar cells all have the capability to act as stem cells in the pancreas (6, 22, 26). Nevertheless, the functional data presented here provide strong evidence that DCAMKL-1 expressing cells have clonogenic capacity in vitro and display some evidence of pancreatic lineage determination in an isograft model. Further studies in transgenic lineage tracing model models will likely be required to fully answer these lingering questions.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-065887, DK-002822 OCAST-AR 101-030, and CA-137482 to C. W. Houchen, Oklahoma University Advanced Immunohistochemistry & Morphology Core, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Oklahoma City.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Michael Bronze, Chairman of the Department of Medicine University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center for support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham EJ, Kodama S, Lin JC, Ubeda M, Faustman DL, Habener JF. Human pancreatic islet-derived progenitor cell engraftment in immunocompetent mice. Am J Pathol 164: 817–830, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agudo J, Ayuso E, Jimenez V, Salavert A, Casellas A, Tafuro S, Haurigot V, Ruberte J, Segovia JC, Bueren J, Bosch F. IGF-I mediates regeneration of endocrine pancreas by increasing beta cell replication through cell cycle protein modulation in mice. Diabetologia 51: 1862–1872, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirulli V, Crisa L, Beattie GM, Mally MI, Lopez AD, Fannon A, Ptasznik A, Inverardi L, Ricordi C, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Reisfeld RA, Hayek A. KSA antigen Ep-CAM mediates cell-cell adhesion of pancreatic epithelial cells: morphoregulatory roles in pancreatic islet development. J Cell Biol 140: 1519–1534, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corti S, Locatelli F, Papadimitriou D, Donadoni C, Salani S, Del Bo R, Strazzer S, Bresolin N, Comi GP. Identification of a primitive brain-derived neural stem cell population based on aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Stem Cells 24: 975–985, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, Wicha MS. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Devel 17: 1253–1270, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA. Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature 429: 41–46, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannakis M, Stappenbeck TS, Mills JC, Leip DG, Lovett M, Clifton SW, Ippolito JE, Glasscock JI, Arumugam M, Brent MR, Gordon JI. Molecular properties of adult mouse gastric and intestinal epithelial progenitors in their niches. J Biol Chem 281: 11292–11300, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development 129: 2447–2457, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen J, Heller RS, Funder-Nielsen T, Pedersen EE, Lindsell C, Weinmaster G, Madsen OD, Serup P. Independent development of pancreatic alpha- and beta-cells from neurogenin3-expressing precursors: a role for the notch pathway in repression of premature differentiation. Diabetes 49: 163–176, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson KA, Dursun U, Jordan N, Gu G, Beermann F, Gradwohl G, Grapin-Botton A. Temporal control of neurogenin3 activity in pancreas progenitors reveals competence windows for the generation of different endocrine cell types. Dev Cell 12: 457–465, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MH, Cierpicki T, Derewenda U, Krowarsch D, Feng Y, Devedjiev Y, Dauter Z, Walsh CA, Otlewski J, Bushweller JH, Derewenda ZS. The DCX-domain tandems of doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase. Nat Struct Biol 10: 324–333, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechner A, Leech CA, Abraham EJ, Nolan AL, Habener JF. Nestin-positive progenitor cells derived from adult human pancreatic islets of Langerhans contain side population (SP) cells defined by expression of the ABCG2 (BCRP1) ATP-binding cassette transporter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293: 670–674, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CS, Perreault N, Brestelli JE, Kaestner KH. Neurogenin 3 is essential for the proper specification of gastric enteroendocrine cells and the maintenance of gastric epithelial cell identity. Genes Dev 16: 1488–1497, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May R, Riehl TE, Hunt C, Sureban SM, Anant S, Houchen CW. Identification of a novel putative gastrointestinal stem cell and adenoma stem cell marker, doublecortin and CaM kinase-like-1, following radiation injury and in adenomatous polyposis coli/multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Stem Cells 26: 630–637, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May R, Sureban SM, Hoang N, Riehl TE, Lightfoot SA, Ramanujam R, Wyche JH, Anant S, Houchen CW. Doublecortin and CaM kinase-like-1 and leucine-rich-repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor mark quiescent and cycling intestinal stem cells, respectively. Stem Cells 27: 2571–2579, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moll R, Divo M, Langbein L. The human keratins: biology and pathology. Histochem Cell Biol 129: 705–733, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niemeyer GP, Hudson J, Bridgman R, Spano J, Nash RA, Lothrop CD. Isolation and characterization of canine hematopoietic progenitor cells. Exp Hematol 29: 686–693, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollack PF, Wood JG, Solomon T. Effect of secretin on growth of stomach, small intestine, and pancreas of developing rats. Dig Dis Sci 35: 749–758, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purkis PE, Steel JB, Mackenzie IC, Nathrath WB, Leigh IM, Lane EB. Antibody markers of basal cells in complex epithelia. J Cell Sci 97: 39–50, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schonhoff SE, Giel-Moloney M, Leiter AB. Neurogenin 3-expressing progenitor cells in the gastrointestinal tract differentiate into both endocrine and non-endocrine cell types. Dev Biol 270: 443–454, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwitzgebel VM, Scheel DW, Conners JR, Kalamaras J, Lee JE, Anderson DJ, Sussel L, Johnson JD, German MS. Expression of neurogenin3 reveals an islet cell precursor population in the pancreas. Development 127: 3533–3542, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seaberg RM, Smukler SR, Kieffer TJ, Enikolopov G, Asghar Z, Wheeler MB, Korbutt G, van der Kooy D. Clonal identification of multipotent precursors from adult mouse pancreas that generate neural and pancreatic lineages. Nat Biotechnol 22: 1115–1124, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Hide T, Dirks PB. Cancer stem cells in nervous system tumors. Oncogene 23: 7267–7273, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res 63: 5821–5828, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 432: 396–401, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soria B, Bedoya FJ, Martin F. Gastrointestinal stem cells. I. Pancreatic stem cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289: G177–G180, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sossey-Alaoui K, Srivastava AK. DCAMKL1, a brain-specific transmembrane protein on 13q12.3 that is similar to doublecortin (DCX). Genomics 56: 121–126, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sureban SM, May R, Ramalingam S, Subramaniam D, Natarajan G, Anant S, Houchen CW. Selective blockade of DCAMKL-1 results in tumor growth arrest by a Let-7a MicroRNA-dependent mechanism. Gastroenterology 137: 649–659, 659 e1–2, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamaki S, Eckert K, He D, Sutton R, Doshe M, Jain G, Tushinski R, Reitsma M, Harris B, Tsukamoto A, Gage F, Weissman I, Uchida N. Engraftment of sorted/expanded human central nervous system stem cells from fetal brain. J Neurosci Res 69: 976–986, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wicha MS, Liu S, Dontu G. Cancer stem cells: an old idea—a paradigm shift. Cancer Res 66: 1883–1890; discussion 1895–1886, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu X, D'Hoker J, Stange G, Bonne S, De Leu N, Xiao X, Van de Casteele M, Mellitzer G, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Bouwens L, Scharfmann R, Gradwohl G, Heimberg H. Beta cells can be generated from endogenous progenitors in injured adult mouse pancreas. Cell 132: 197–207, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zulewski H, Abraham EJ, Gerlach MJ, Daniel PB, Moritz W, Muller B, Vallejo M, Thomas MK, Habener JF. Multipotential nestin-positive stem cells isolated from adult pancreatic islets differentiate ex vivo into pancreatic endocrine, exocrine, and hepatic phenotypes. Diabetes 50: 521–533, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.