Abstract

Some quantitative behavioral studies in the USA have concluded that bisexually behaving Latino men are less likely than White men to disclose to their female partners that they have engaged in same-sex risk behavior and/or are HIV-positive, presumably exposing female partners to elevated risk for HIV infection. Nevertheless, very little theoretical or empirical research has been conducted to understand the social factors that promote or inhibit sexual risk disclosure among Latino men who have sex with men (MSM), and much of the existing literature has neglected to contextualize disclosure patterns within broader experiences of stigma and social inequality. This paper examines decisions about disclosure of sex work, same-sex behavior, and sexual risk for HIV among male sex workers in two cities in the Dominican Republic. Data derive from long-term ethnography and qualitative in-depth interviews with 72 male sex workers were used to analyze the relationships among experiences of stigma, social inequality, and patterns of sexual risk disclosure. Thematic analysis of interviews and ethnographic evidence revealed a wide range of stigma management techniques utilized by sex workers to minimize the effects of marginality due to their engagement in homosexuality and sex work. These techniques imposed severe constraints on men’s sexual risk disclosure, and potentially elevated their own and their female partners’ vulnerability to HIV infection. Based on the study’s findings, we conclude that future studies of sexual risk disclosure among ethnic minority MSM should avoid analyzing disclosure as a decontextualized variable, and should seek to examine sexual risk communication as a dynamic social process constrained by hierarchical systems of power and inequality.

Keywords: Bisexuality, HIV/AIDS, Sexual risk disclosure, Stigma, Male sex work, Dominican Republic, Social inequality

Introduction

The questions of when and under what circumstances individuals disclose information about their sexual risk behaviors or HIV status to their primary partners have been central to recent scholarly debates about the epidemiological importance of sexual disclosure in the age of AIDS. As some research has suggested that rising infection rates among ethnic minority women may be related to the clandestine bisexual behavior of their male partners (Bingham et al., 2002; Chu, Peterman, Doll, Buehler, & Curran, 1992; Lehner & Chiasson, 1998; Stokes, McKirnan, Burzette, & Vanable, 1993; Stokes, McKirnan, Doll, & Burzette, 1996; Stokes & Peterson, 1998), scholars have called for attention to the role of HIV risk disclosure – direct communication with sexual partners about one’s sexual risk for or infection with HIV – as a potentially important factor influencing HIV transmission. A number of researchers have argued that disclosure of sexual orientation, sexual risk behavior, or HIV serostatus by bisexually behaving men may each play a role in preventing new HIV infections (Agronick et al., 2004; Bingham et al., 2002; Chu et al., 1992; Lehner & Chiasson, 1998; Montgomery, Mokotoff, Gentry, & Blair, 2003; Norman, Kennedy, & Parish, 1998; Shehan et al., 2003; Stokes et al., 1993; Stokes et al., 1996; Stokes & Peterson, 1998). Such assertions are driven by the belief that the disclosure of HIV risk may improve communication between sexual partners and, thereby, increase the likelihood that safer sex can be consistently practiced (Simoni & Pantalone, 2004).

Nevertheless, some research suggests that disclosure of HIV serostatus does not necessarily ensure safer sex practices (Crepaz & Marks, 2003; Marks & Crepaz, 2001; Marks et al., 1994; Millett, Malebranche, Mason, & Spikes, 2005; Serovich & Mosack, 2003) and that nondisclosure of HIV status does not necessarily translate into higher sexual risk for HIV (Marks & Crepaz, 2001; Millett et al., 2005; Poppen, Reisen, Zea, Bianchi, & Echeverry, 2005). Similarly, while some scholars have suggested that the disclosure of bisexual behavior to female partners is associated with increased condom use (Wolitski, Rietmeijer, Goldbaum, & Wilson, 1998), other research has not detected such effects (Kalichman, Roffman, Picciano, & Bolan, 1998). Compounding such inconsistencies, one recent meta-analysis of the literature on HIV serostatus disclosure has pointed to serious limitations in existing research due in part to a paucity of contextualized studies of how disclosure is actually understood and practiced in specific populations (Simoni & Pantalone, 2004).

Drawing on ethnographic and qualitative interview data with a population of bisexually behaving male sex workers in the Dominican Republic, this paper argues that much of the inconsistency in findings on HIV risk disclosure is related to the tendency to focus on individual-level or relational factors while neglecting the contextual factors that inform bisexually behaving men’s decisions to disclose. Research should treat disclosure as a dynamic social process that unfolds within specific social, cultural, and economic contexts. Further, we suggest that studies of HIV risk disclosure would greatly benefit from existing social science approaches to stigma and social inequality as they have been applied globally in public health (Farmer, Connors, & Simmons, 1996; Link, 2001; Link & Phelan, 2006; Parker, 2001; Parker & Aggleton, 2003; Parker, Easton, & Klein, 2000). This would allow researchers to examine the ways specific populations make decisions about disclosure in relation to the multiple social norms and power structures that they face in their daily lives.

Research among Latino men who have sex with men (MSM) is particularly relevant in this regard. Numerous qualitative studies have shown that these men are likely to encounter severe structural disadvantages, such as poverty, discrimination, disconnection from kinship structures, interpersonal violence, elevated unemployment, and low educational attainment (Carrillo, 2002; Díaz, 1998; Díaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001; Díaz, Ayala, & Marin, 2000; Kulick, 1998; Lancaster, 1992; Padilla, 2007; Padilla, Vásquez del Aguila, & Parker, 2007; Prieur, 1998). Despite this, much of the public health research on HIV risk disclosure among Latino MSM has focused on decontextualized correlations, such as the finding that Latino men are less likely to disclose their same-sex sexual behaviors (McKirnan, Stokes, Doll, & Burzette, 1995), to identify as gay (Goldbaum et al., 1998; McKirnan et al., 1995; Montgomery et al., 2003), and to report sexual interactions with both females and males than are White MSM (Montgomery et al., 2003). While some serostatus disclosure studies have suggested that disclosure may be inhibited by the stigma of homosexuality in the Latino community (Zea, Reisen, Poppen, Echeverry, & Bianchi, 2004) or by a desire to protect family members from a damaged social reputation (Mason, Marks, Simoni, Ruiz, & Richardson, 1995), quantitative public health studies of HIV risk disclosure have generally failed to develop analyses that link the dynamics of disclosure to the social, cultural, and structural context of Latino and Latin American communities. Indeed, one recent study of HIV serostatus disclosure among HIV-positive Latino MSM concluded that “programs that encourage disclosure of serostatus…may not affect sexual risk behaviors unless they deal with the responses to the resulting knowledge of seroconcordance or discordance” (Poppen et al., 2005, p. 235).

The present analysis derives from a three-year, multi-method ethnographic study of male sex workers in the Dominican Republic, most of whom were bisexually behaving men with stable female partners (see Methods and background and Padilla, 2007). Male sex work in the Caribbean has received some attention in social scientific research – primarily as regards exchanges between Caribbean men and foreign women (Brennan, 2004; Kempadoo, 1999; Phillips, 1999; Press, 1978; Pruitt & LaFont, 1995). Nevertheless, little is known about the relationships among social stigma, social inequality, and HIV risk disclosure among male sex workers and their local female partners. As far as we are aware, this study represents the first analysis of these issues in the region.

Methods and background

Our research seeks to examine how members of a specific population of bisexually behaving Latin American men narrate real or potential moments of sexual disclosure with their partners and families, and to describe how experiences of stigma and social inequality shape their decisions, perceptions, and practices of disclosure. Data derive from an ethnographic study of male sex workers led by the first author in two cities on the southern coast of the Dominican Republic (Santo Domingo and Boca Chica) between 1999 and 2002, and include ethnographic observations, in-depth semi-structured interviews (SSI) with 72 male sex workers, and a demographic, behavioral and social survey with 200 sex workers. A more detailed and extensive description of the methods in this study can be found in Padilla (2007). The present analysis draws primarily on the SSI, although survey and ethnographic data are also presented insofar as they provide a context for understanding men’s experiences of stigma and disclosure.

Research on sensitive topics such as sexuality and HIV/AIDS may encounter threats to the validity of data obtained through self-reported methods (Lee, 1993; Rodgers, Billy, & Udry, 1982; Wight & West, 1999). However, a growing body of scholarly work on HIV/AIDS suggests that ethnographic approaches can reduce these threats by maximizing the researcher’s direct interaction with participants in naturally occurring situations, engaging in more informal and open-ended forms of inquiry, and enabling the gradual development of rapport and trust between researchers and participants (Herdt, 2001; Herdt & Lindenbaum, 1992; Parker & Ehrhardt, 2001). The present study took advantage of these methodological benefits by incorporating several months of participant observation in sex work areas prior to recruitment into the SSI, and by recruiting sex workers purposively based in part on the extent of rapport established between the research team and potential participants. Initial access to sex work areas was facilitated by the collaboration of two Dominican co-investigators (Sánchez Marte and Arredondo Soriano), who are well-known and respected HIV/AIDS educators and community leaders from a local non-profit AIDS organization, Amigos Siempre Amigos. The first phase of the research involved nine months of participant observation by the research team to describe and map a wide range of sex work areas, to establish rapport with a large number of sex workers, and to identify a set of social networks through which participants could be subsequently recruited into the SSI. In addition to selecting participants with whom sufficient rapport had been established, the research design sought to diversify the sample by selecting subjects from a wide range of social networks and sex work environments. Nevertheless, the purposive sampling technique employed does not approximate a random sample of sex workers or permit unqualified generalizations to a larger population. We believe that the combination of ethnographic methodologies, extensive rapport-building prior to the SSI, and the research team’s experience with the population all contributed to more valid responses from subjects regarding experiences of stigma and disclosure.

Interpretation consisted of thematic analysis of sex workers’ narratives in response to a set of semi-structured interview questions on (1) experiences of stigma and social inequality related to sex work and homosexual behavior; (2) strategies to manage stigma related to either sex work or homosexual behavior; (3) men’s predictions regarding social stigma upon real or imagined disclosure of sex work and/or homosexual behavior; and (4) the effects of stigma and social inequality on men’s decisions to employ risk reduction techniques with female partners. Transcripts were imported into Atlas-TI and coded for themes related to our interest in the relationships among experiences of stigma, social inequality, disclosure, and HIV risk. Analysis used a combination of open coding procedures with a sub-sample of interview transcripts, followed by a recoding of all transcripts using a fixed set of validated codebook definitions.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the sample, by research site. (In seven cases, the brief sociodemographic surveys that followed each interview could not be feasibly conducted, lowering the total number of cases shown in Table 1 to 65.) Both research sites are tourist areas in the Dominican Republic, attracting significant numbers of young Dominicans who regularly or intermittently exchange sex for money with tourists, as documented in numerous studies (Brennan, 2004; De Moya & Garcia, 1998; De Moya & Garcia, 1996; De Moya, Garcia, Fadul, & Herold, 1992; Kerrigan et al., 2003; Padilla, 2007; Tabet et al., 1996; Vásquez, Ruiz, & De Moya, 1991; Vásquez, Ruíz, & De Moya, 1990). Only one epidemiological study of HIV/AIDS among Dominican MSM was conducted in this area a decade ago, and reported the HIV prevalence among “gigolos” (presumably similar to the men considered here) at 6.5% (Tabet et al., 1996).

Table 1.

Characteristics of in-depth interview sample, by research site (N = 72)

| % (n) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Santo Domingo (n = 42)a | Boca Chica (n = 23)a | |

| Age (years) | Mean age = 24.8 | Mean age = 26.1 |

| 18–20 | 26.2 (11) | 26.0 (6) |

| 21–25 | 28.6 (12) | 21.7 (5) |

| 26–30 | 21.4 (9) | 26.1 (6) |

| 31–35 | 11.9 (5) | 17.4 (4) |

| >36 | 4.8 (2) | 4.3 (1) |

| No response | 7.1 (3) | 4.3 (1) |

| % With at least one stable partner | 59.5 (25) | 39.1 (9) |

| % Of above whose stable partner(s) are male | 20.0 (5) | 11.1 (1) |

| % Of above whose stable partner(s) are female | 48.0 (12) | 66.7 (6) |

| % Of above whose stable partners are of both sexes | 32.0 (8) | 22.2 (2) |

| % Living with family members | 71.4 (30) | 56.5 (13) |

| % Married | 29.0 (12) | 8.7 (2) |

| % With children | 45.2 (19) | 60.9 (14) |

Sociodemographic data unavailable for seven interviewees (four in Santo Domingo, three in Boca Chica).

Key characteristics of this sample include the fact that while the mean age was only 25 years, half of the participants already had children, and approximately the same proportion had stable female partners. The survey reported in Padilla (2007) demonstrates that while nearly all participants had both male and female sex partners, only 3% identified themselves as either gay or homosexual. Ethnographic and interview evidence shows that while approximately a quarter of the men in the SSI sample were married to women, the vast majority of them had one or more women they considered girlfriends at any given time, and women, rather than men, were described as participants’ erotic and relational ideal. Sexual exchanges with men were generally described as “por la necesidad” (out of necessity), and they often provided household and personal income upon which men depended (Padilla, 2007).

Results

Experiences of stigma and inequality

At age 9, “Miguel”,1 32 years of age at the time of his interview, left his family home and became, in his words, “a street kid”: “I was raised in the street. Mainly I was raised with the tourists. I worked with them. Some were gays and I stayed with them, and that’s how my life went. I raised myself alone.” Two years after leaving home, he relocated from his home town of La Romana to Santo Domingo to try his luck in the city:

Well, when I came to Santo Domingo the first time, I began working with a triciclo [tricycle, used to pick up recyclable material] in the street…looking for bottles, looking for cardboard in the street. And I always stopped there in El Conde [a popular tourist area] around a hotel that was called the —, and they [the tourists] always waved to me, and they started to give me things, and they said ‘come,’ and from there I continued. I went every day, I passed by every day, since then I knew that they gave me— that they gave me a sandwich, they gave me ten dollars, they gave me five pesos…And I got a person, a guy, an American friend, and from the age of twelve I stayed almost– almost four or five years working with him in the hotel. I was the one who—who did it to him. And there I stayed.

Like Miguel, many of the sex workers in this study had become street children at an early age, often working as limpiabotas (shoe-shiners) or chiriperos (street vendors) –occupations which resulted in periods of extreme deprivation. Among study participants who became street children at a young age, stories of initiation into sex work often began by describing a period of vulnerability or homelessness resulting from abuse, alcoholism, neglect, or poverty in the natal home. Leonardo, an 18 year old in Santo Domingo, for example, told a story of his first transaction with a Puerto Rican tourist at the age of 10, after being offered money, food, and clothing while shining the man’s shoes. After going to a short-term motel and enduring a “disgusting” experience, he gained knowledge of the trade from experienced sex workers and now considers the work, along with many other participants, the best way to get “dinero facil” (easy money).

While a minority of participants did express satisfaction with the benefits of sex work, the phrase “easy money,” which emerged as a theme in men’s descriptions of their motivations for engaging in sex work, must be understood in the context of the poverty and underemployment in which most of these men live. As the Dominican economy has moved from male-dominated industries such as agriculture to the service industry of tourism, informal exchanges with tourists have become a popular coping strategy among underemployed male adolescents and young men (Padilla, 2007). Money is, therefore, only “easy” in a relative sense, since the meanings of this term must be understood within the highly constrained opportunities available to poor men such as Miguel and Leonardo. German, 24, described as follows this tension between the ‘ease’ of sex work and the larger economic context:

Sometimes when you want to see things as easy, you accept them. Because that’s also our error – the so-called ‘bugarrones’ [a local term for male sex workers] – because the majority of us don’t like to work. I include myself. Because it’s not that I don’t like to work – I’ve always worked – but the thing is that the kind of work we can do is so hard, and so poorly paid. Working like a ‘normal’ person, I mean. And it’s always like that. Nothing. So here we are. And this is our life.

German’s reference to “normal people” reflects another theme in the interviews: sex workers’ feeling that they are, in the words of one participant, “fuera de la socie-dad” (outside of society). “Mainly the society catalogues us as unequal, like a dead person,” Eduardo, 19, commented in one interview. References to the desire to be “normal” among participants were related to the belief that they were falling short of social expectations regarding appropriate modes of work and masculine behavior. Even among participants who expressed satisfaction with their occupation, sex work – particularly sex work with male clients – was almost universally believed to be harmful and potentially result in mental, physical, or moral damage. For instance, Estevan, 27, observed:

I tell a lot of people, mainly young men, not to have sex with other men, because it’s a bad thing, a sin with God, and that their families should help them to not get to that point…It’s a big sin, but with help you won’t do it. Without help, you get pushed to do it, because there are many foreigners who come here to have fun.

Sex workers’ narratives often made reference to the tension between social proscriptions against homosexual behavior and the danger of “getting pushed into” sexual exchanges with male tourists. As suggested in Estevan’s comment above, moral and religious condemnations against homosexuality loomed large in most participants’ experience, and often provoked unsolicited explanations during interviews by men who sought to justify participation in stigmatizing sexual behaviors by referencing their dire economic circumstances. When asked about their sexual attraction toward men, for example, most participants denied any such attraction, sought to clarify their identity as “normal men,” and commented that they only have sex with men “out of necessity.”

Stigma management techniques

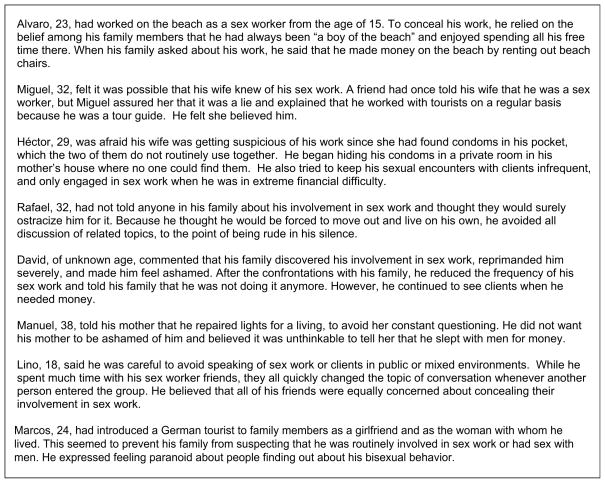

The tension between economic dependence on sex work and the dual stigmas of prostitution and homosexual behavior resulted in men’s frequent use of what Goffman has described as “stigma management techniques” –modes of interaction that reduce the negative effects of stigma on one’s social status (Goffman, 1963). In this section, we summarize the most common stigma management techniques used with family members and stable female partners. We use three cases to illustrate some of the complex ways that sex workers manage stigma in a range of social contexts and situations. Fig. 1 summarizes a range of specific stigma management techniques described by sex workers in the interviews.

Fig. 1.

Examples of sex workers’ stigma management techniques.

Case 1. Hernán, 18, lived with several family members and shared expenses. He explained in an interview that nobody in his household knew about his involvement in sex work, and believed that they would reprimand him severely and perhaps force him to live on the street. He observed that it would be particularly damaging if his mother found out, because she would be disappointed in him and it would bring the family vergüenza (shame). He attempted to keep his engagement in sex work concealed from the community. He did not like to be seen in public with gay clients, especially if they were “obvious”, because he did not want people to think that he was homosexual or a sex worker. He commented that if people began telling stories about him, he would be ridiculed and would be too ashamed to live in his neighborhood.

The desire to preserve family honor was a significant theme, and created feelings of acute shame when participants discussed real or potential moments of disclosure. Indeed, open communication with family was often viewed as impossible, since it would represent a great shame on the household. Like Hernán, a number of participants described the need to avoid public association with openly gay men, since this could fuel suspicion among family, friends, and neighbors, damaging one’s masculine reputation. “Here, maricones (fags) are very low people,” explained 26-year-old Samuel, who preferred to go to “normal places” and to avoid gay bars and discos in the course of his work. Daniel, 18, described how he was forced to abandon a well-paying regular client because he expected openness about their relationship and was excessively “obvious” in his mannerisms.

Case 2. Orlando, 27, joked in his interview about the problems that had developed as a result of his involvement with two women, as well as his attempts to prevent his sister, with whom he was then living, from learning about his sexual exchanges with men. He felt he had to frequently tell “little lies” to his family and girlfriends in order to keep them from suspecting he was a sex worker. To “kill the bad thoughts” of the neighbors, he occasionally came by the house with his girlfriends, a technique he believed would dispel any doubts about his homosexual behavior. When he had to be away from home to see clients, he would tell his primary girlfriend that he was out of town painting houses, a story he felt she believed.

Orlando’s case illustrates two common stigma management techniques, one associated with concealing participation in sex work and the other with avoiding suspicion about engagement in homosexual behavior. First, as suggested by his need to invent a painting job, the income provided by sex work created dilemmas for men as they negotiated the suspicion of family members and partners. The inexplicable appearance of cash in the context of a pervasive informal tourism economy and the general commonality of sex work tended to raise suspicion in the eyes of co-resident family and partners. Ironically, this even made some participants reticent to contribute financially to the household, due to the potential interrogation this could entail. Since most of the participants resided with family members and/or spouses (see Table 1), they faced the regular imperative to conceal their sex work income or provide a reasonable explanation for the money they earned, often producing elaborate stories about invented jobs.

Another theme reflected in Orlando’s narrative is reflected in his desire to maintain an image of normative masculine sexuality. A number of participants produced real or invented girlfriends when families or neighbors became suspicious, in an effort to provide a convincing show of heterosexual normalcy.

Case 3. Jaime, 32, did not speak directly with his family about his work or sex with men, but believed they suspected. While his mother had often interrogated him about the source of his money and threatened to throw him out of the house for being a “delinquent,” he had managed to provide reasonable explanations for his income. More recently, still in the absence of an explicit conversation, his mother had begun to make comments that he should “take care of himself,” and she had even told him, “Look, you need to use a condom.” Jaime had not acknowledged the implication of these comments, and continued to invent excuses for his absences from home.

Like Jaime, a significant proportion of participants described using a range of more subtle or indirect forms of communication with family members and partners, an approach that allowed them to tacitly acknowledge a certain shared understanding without disrupting the relationship with frank sexual disclosures. While almost no men in this study described openly disclosing either their participation in sex work or homosexual activity, veiled comments such as “take care of yourself” were ways that some family members communicated a level of understanding and concern, or perhaps offered the opportunity for more direct communication. These dynamics allowed both sex workers and their families to maintain a comfortable ambiguity about the stigma itself, since the elaborate techniques that these men used to manage stigma permitted alternative explanations for suspicious activities or associations.

Contextualizing sexual risk disclosure

As with other studies on HIV-related risk behavior in the context of marriage (Hirsch, 2003; Hirsch, Higgins, Bentley, & Nathanson, 2002), the men in this study expressed a strong resistance to using condoms with their steady female partners whom they considered de confianza (trustworthy). While self-reported condom use with male clients was quite high on the structured survey for this study, with 82% reporting they had “always” used condoms with their male clients, 14% of men with regular male clients indicated they had never used condoms with these partners. Further, the in-depth interviews strongly suggested that actual condom use with clients was more inconsistent than reflected in the structured survey, creating significant dilemmas for many participants regarding the possibility of becoming infected with HIV and/or placing their female partners at risk. The cases of Mauricio and Samuel are illustrative of these patterns.

Case 1: Mauricio, 30, reported using condoms with all of his male clients. He strongly believed in the need to use condoms to protect both himself and his two steady girl-friends, neither of whom was aware about the nature of his work. He did not use condoms with either of these women. He had had a recent incident with a male client in which the condom broke, causing him much anxiety about infecting himself and his two girlfriends, anxiety that escalated when he later developed a persistent cough. None of his family and friends knew about his involvement in sex work, and he felt he could never tell them. While he indicated that condom use usually occurs in the beginning of his relationships with women, he stopped using condoms as soon as he trusted his partners.

Case 2: Samuel, 26, said he firmly believed in using condoms always with male clients, although he did not use condoms with either of his two girlfriends because he trusted them, nor did he use condoms with the one regular male client with whom he had also developed trust and affection. When asked about other casual sex partners, he said that he did not use condoms with women he trusted and always used condoms with women he did not trust. He had not had an HIV test out of fear, and because he believed that he would die sooner of anxiety if he received a positive result.

Similar to Samuel and Mauricio, many sex workers articulated a model of selective condom use in which condoms were to be consistently used in all transactions with male clients in order to protect themselves and their trusted female partners from HIV. Nevertheless, in cases when protection was foregone with male clients due to developing trust, pressure from regular clients, temporary errors of judgment, alcohol or drug use, or broken condoms, these men often experienced intense fear about HIV infection and the potential for infecting their wives and girlfriends. Oscar, 37, for example, had had unprotected sex with a tourist a few days before the interview, and commented that while “the fear kills me,” he could not tell anyone about his anxieties, which were exacerbated by the recent AIDS-related death of a close friend.

While many sex workers expressed great fear about HIV infection and the health of their wives and girlfriends, they very rarely disclosed moments of sexual risk behavior to their partners, nor was condom use typically initiated as an interim protective strategy. The latter was partly related to the importance of unprotected sex as a symbol of relational trust, as illustrated by Lorenzo, 26, who when asked why he did not begin using condoms with his steady girlfriend to avoid his expressed anxiety about infecting her, commented, “Can you imagine after four years me telling her we’re going to use condoms! What would she think?” As with most of the participants in this study, Lorenzo’s fears about HIV infection and the desire to protect his girlfriend were overshadowed by anxieties about the potential consequences of disclosure.

Despite these constraints on disclosure, a few participants had established more open communication with their families and partners. Alejandro, 27, for example, observed that he did nothing to conceal his involvement in sex work, which he had discussed openly with his parents and primary partner, and stressed that he always used condoms to keep himself and his family safe. Further, it should be emphasized that a number of participants who had not disclosed their involvement in sex work or homosexual behavior, nevertheless, articulated a strong sense of familial responsibility. For example, 83% of fathers in the survey portion of the study indicated that they helped support their children with their sex work income, and the cost of raising children was often cited as a primary reason for participation in sex work. The latter is illustrated by Martín, 33, who when asked whether his income from sex work covered all his expenses, responded, “No, it doesn’t cover all of my expenses, but it helps me to take care of my children, which is the most important thing.” Thus, while direct sexual disclosure was rare among participants, it cannot be concluded that these men possess no sense of responsibility toward their partners and families. However, this responsibility rarely translated into direct disclosures or consistent condom use.

Discussion

The participants in this study experienced significant social stigma due to their violation of norms of sexual behavior and modes of work. Interview and ethnographic evidence demonstrates sex workers’ use of stigma management techniques to minimize the effects of these dual stigmas, including the invention of jobs to justify sex work income, the creation of alibis for extended absences, and the production of girlfriends to perform heterosexual normalcy. While many of these men described great fear about HIV infection or infecting their partners, the potential for disclosure of HIV risk was overwhelmed by their anxieties about further stigmatization and their investments in the stigma management techniques that they had integrated into their identities.

Sex workers’ attempts to mitigate stigma must be viewed in relation to the conditions of inequality and structural violence that they routinely confront. Many of these men had been socialized into the sex trade from an early age, often as a consequence of homelessness, poverty, or abusive environments. As underemployed men in an era of decline in opportunities for wage labor, informal tourism work and instrumental sexual exchanges provided a means to make ends meet in the context of constrained economic options. The stigmas of sex work and homosexuality, therefore, functioned in synergy with social inequalities to raise the stakes of their marginalization, potentially resulting in abandonment by family, alienation by neighbors, or the inability to access shared resources. While participants sought to cope with their marginality by employing a range of stigma management techniques, some described indirect or ambiguous forms of communication with family members that revealed a level of shared understanding about morally questionable behaviors. Participants’ mothers were particularly notable in this regard, sometimes admonishing their sons to “be careful” and to “use condoms” –somewhat vague warnings that, nevertheless, represented the most direct forms of disclosure many of these men experienced.

Our research responds to recent calls in global health for contextualized analyses of HIV/AIDS that address the linkages between stigma and social inequality (Abadía-Barrero & Castro, 2006; Castro & Farmer, 2005; Link & Phelan, 2001, 2006; Padilla, 2007; Padilla et al., 2007; Parker & Aggleton, 2003; Parker et al., 2000). Such approaches are essential in addressing the dynamics of HIV transmission in populations that routinely experience not only social disparagement but also structural disadvantages such as poverty, lack of housing, lack of access to care, and tenuous social support structures. While the public health literature on HIV risk disclosure among ethnic minority MSM has grown in recent years, studies examining how structural factors shape disclosure patterns have been few (see, however, Harawa, Williams, Ramamurthi, & Bingham, 2006), and there is a paucity of research conducted in developing-country settings. The present study’s findings contribute to a contextualized understanding of how experiences of stigma and social inequality shape sexual risk disclosure among a specific population of bisexually behaving, non-gay-identified men in the Dominican Republic. A constraint of this research may be that participants all reported a history of sexual-economic exchanges, suggesting that they may share particular experiences and circumstances that limit their relevance to discussions of HIV/AIDS among the broader population of Latino or Latin American MSM. Nevertheless, the voices of Dominican male sex workers provide a dramatic illustration of the ways that stigma and inequality can converge to shape patterns of sexual risk disclosure among marginalized populations of MSM.

Our findings strongly suggest that individual- or behavioral-level intervention approaches are unlikely to be effective in altering the most important contextual factors that contribute to HIV risk in marginalized populations of MSM. Instead, interventions should be comprehensive and multi-level, extending beyond the MSM population and involving broad-based stigma-reduction initiatives, policy changes to protect sex workers from discrimination, and the creation of community interventions to improve skills for risk communication, social support, and a sense of collective responsibility. Men’s desires to provide for their families and children, as well as their attempts at communication with certain members of their kin networks, may be cultural resources to be tapped by future prevention efforts. Finally, the interconnections between sex work, social stigma, the expanding tourism industry, and the HIV epidemic urgently require attention by the public health system, tourism developers, and civil society, in an effort to alleviate the structural conditions that contribute to vulnerability among sex workers. Global HIV/AIDS research should contribute to this effort by moving beyond the decontextualized correlations that have dominated the literature on disclosure and HIV risk, permitting a more nuanced understanding of how individuals make decisions about disclosure in relation to the social norms, cultural meanings, and hierarchical power structures that they encounter in their daily lives.

Footnotes

All proper names and some location names have been changed for reasons of confidentiality.

The first author would like to thank several agencies which funded portions of the research: the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, Fulbright IIE, the National Science Foundation, the Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program, and the Dominican Republic mission of the United States Agency for International Development. Many thanks to Luis Lizardo at Columbia University for his coding of the in-depth interviews. Finally, the authors would like to thank the courageous men who participated in the research.

Contributor Information

Mark Padilla, Email: padillam@umich.edu.

Daniel Castellanos, Email: hdc2103@columbia.edu.

Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, Email: rg650@columbia.edu.

Armando Matiz Reyes, Email: armandomatiz@gmail.com.

Leonardo E. Sánchez Marte, Email: sanchezleonardo@hotmail.com.

References

- Abadía-Barrero CE, Castro A. Experiences of stigma and access to HAART in children and adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agronick G, O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Doval AS, Duran R, Vargo S. Sexual behaviors and risks among bisexually- and gay-identified young Latino men. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8(2):185–197. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030249.11679.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham T, McFarland W, Shehan DA, LaLota M, Celentano DD, Koblin BA, et al. Unrecognized HIV infection, risk behaviors, and perceptions of risk among young black men who have sex with men – six U.S. cities, 1994–1998. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51(33):733–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. Transnational desires and sex tourism in the Dominican Republic. Durham/London: Duke University Press; 2004. What’s love got to do with it? [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo H. The night is young: Sexuality in Mexico in the time of AIDS. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, Farmer P. Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: from anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(1):53–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.028563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu SY, Peterman TA, Doll LS, Buehler JW, Curran JW. AIDS in bisexual men in the United States: epidemiology and transmission to women. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(2):220–224. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marks G. Serostatus disclosure, sexual communication and safer sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS Care. 2003;15:379–387. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moya A, Garcia R. Three decades of male sex work in Santo Domingo. In: Aggleton P, editor. Men who sell sex: International perspectives on male prostitution and AIDS. London: Taylor & Francis; 1998. pp. 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- De Moya EA, Garcia R. AIDS and the enigma of bisexuality in the Dominican Republic. In: Aggleton P, editor. Bisexualities and AIDS: International perspectives. Bristol, PA: Taylor & Francis; 1996. pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- De Moya EA, Garcia R, Fadul R, Herold E. Report: Sosua sanky-pankies and female sex workers: An exploratory study. Santo Domingo: La Universidad Autonoma de Santo Domingo; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz RM. Latino gay men and HIV. New York: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz RM, Ayala G, Marin BV. Latino gay men and HIV: risk behavior as a sign of oppression. Focus: A Guide to AIDS Research. 2000;15(7):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P, Connors M, Simmons J. Women, poverty, and AIDS. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goldbaum G, Perdue T, Wolitski R, Rietmeijer C, Hedrich A, Wood R. Differences in risk behavior and sources of AIDS information among gay, bisexual and straight-identified men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Harawa NT, Williams JK, Ramamurthi HC, Bingham TA. Perceptions towards condom use, sexual activity, and HIV disclosure among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men: implications for heterosexual transmission. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(4):682–694. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9067-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G. Stigma and the ethnographic study of HIV: problems and prospects. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(2):141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, Lindenbaum S. The time of AIDS: Social analysis, theory, and method. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch J. A courtship after marriage: Sexuality and love in Mexican transnational families. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS, Higgins J, Bentley ME, Nathanson CA. The social constructions of sexuality: marital infidelity and sexually transmitted disease-HIV risk in a Mexican migrant community. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(8):1227–1237. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Roffman RA, Picciano JF, Bolan M. Risk for HIV infection among bisexual men seeking HIV-prevention services and risks posed to their female partners. Health Psychology. 1998;17:320–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempadoo K. Sun, sex and gold: Tourism and sex work in the Caribbean. New York: Rowman & Littlefield; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Ellen JM, Moreno L, Rosario S, Katz J, Celentano DD, et al. Environmental–structural factors significantly associated with condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulick D. Travestí: Sex, gender and culture among Brazilian transgendered prostitutes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster RN. Life is hard: Machismo, danger, and the intimacy of power in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Doing research on sensitive topics. London: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lehner T, Chiasson MA. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexual behaviors in bisexual African-American and Hispanic men visiting a sexually transmitted disease clinic in New York City. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147(3):269–272. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Stigma: many mechanisms require multifaceted responses. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale. 2001;10(1):8–11. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00008484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528–529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B, Phelan J. Bethesda, MD: 2001. Background paper: On stigma and its public health implications, stigma and global health: Developing a research agenda. Available from < http://www.stigmaconference.nih.gov/FinalLinkPaper.html>. [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Stokes JP, Doll L, Burzette RG. Bisexually active men: social characteristics and sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 1995;32:64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Crepaz N. HIV-positive men’s sexual practices in the context of self-disclosure of HIV status. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;27:79–85. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200105010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Ruiz MS, Richardson JL, Reed D, Mason HR, Sotelo M. Anal intercourse and disclosure of HIV infection among seropostiive gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1994;7:866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason HR, Marks G, Simoni JM, Ruiz MS, Richardson JL. Culturally sanctioned secrets? Latino men’s nondisclosure of HIV infection to family, friends, and lovers. Health Psychology. 1995;14(1):6–12. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett G, Malebranche D, Mason B, Spikes P. Focusing “down low”: bisexual black men, HIV risk and heterosexual transmission. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(7 Suppl):52S–59S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery JP, Mokotoff ED, Gentry AC, Blair JM. The extent of bisexual behaviour in HIV-infected men and implications for transmission to their female sex partners. AIDS Care. 2003;15(6):829–837. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001618676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman LR, Kennedy M, Parish K. Close relationships and safer sex among HIV-infected men with hemophilia. AIDS Care. 1998;10:339–354. doi: 10.1080/713612420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla M. Caribbean pleasure industry: Tourism, sexuality, and AIDS in the Dominican Republic. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB, Vásquez del Aguila E, Parker RG. Globalization, structural violence, and LGBT health: a cross-cultural perspective. In: Meyer I, Northridge ME, editors. The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. Sexuality, culture, and power in HIV/AIDS research. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2001;30:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Easton D, Klein C. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. AIDS. 2000;14(1) doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Ehrhardt A. Through an ethnographic lens: ethnographic methods, comparative analysis and HIV/AIDS research. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(2):105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JL. Tourist-oriented prostitution in Barbados: the case of the beach boy and the white female tourist. In: Kempadoo K, editor. Sun, sex, and gold: Tourism and sex work in the Caribbean. Boulder: Rowman & Littlefield; 1999. pp. 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Poppen PJ, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ. Serostatus disclosure, seroconcordance, partner relationship, and unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-positive Latino MSM. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2005;17:228–238. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.227.66530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press CM. Reputation and respectability reconsidered: hustling in a tourist setting. Caribbean Issues. 1978;4(1):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Prieur A. Mema’s house, Mexico city: On transvestites, queens, and machos. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt D, LaFont S. For love and money: romance tourism in Jamaica. Annals of Tourism Research. 1995;22(2):422–444. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JL, Billy JOG, Udry JR. The rescission of behaviors: inconsistent responses in adolescent sexuality data. Social Science Research. 1982;11:280–296. [Google Scholar]

- Serovich JM, Mosack KE. Reasons for HIV disclosure or non-disclosure to casual sexual partners. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2003;15:70–80. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.70.23846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehan DA, LaLota M, Johnson DF, Celentano D, Koblin BA, Torian LV, et al. HIV/STD risks in young men who have sex with men who do not disclose their sexual orientation – six U.S. cities, 1994–2000. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52(5):83–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Pantalone DW. Secrets and safety in the age of AIDS: does HIV disclosure lead to safer sex? Topics in HIV Medicine. 2004;12(4):109–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes J, McKirnan D, Burzette B, Vanable P. Female sexual partners of bisexual men: what they don’t know might hurt them. International Conference on AIDS. 1993;9(1):111. [Abstract no. WS-D108-115] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, McKirnan DJ, Doll L, Burzette RG. Female partners of bisexual men: what they don’t know might hurt them. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20:267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Homophobia, self-esteem, and risk for HIV among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1998;10:278–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabet SR, de Moya EA, Holmes KK, Krone MR, de Quinones MR, de Lister MB, et al. Sexual behaviors and risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 1996;10(2):201–206. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez RE, Ruíz C, De Moya EA. Motivación y uso de condones en la prevención del SIDA entre muchachos de la calle trabajadores sexuales. Santo Domingo: UASD/PROCETS; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez RE, Ruiz C, DeMoya EA. AIDS prevention motivation and condom use among Dominican male street kid sex workers, Santo Domingo, 1990. International Conference on AIDS. 1991;7(2):71. [Abstract no. TH.D.61] [Google Scholar]

- Wight D, West P. Poor recall, misunderstandings and embarrassment: interpreting discrepancies in young men’s reported heterosexual behavior. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 1999;1(1):55–78. doi: 10.1080/136910599301166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski RJ, Rietmeijer CA, Goldbaum GM, Wilson RM. HIV serostatus disclosure among gay and bisexual men in four American cities: general patterns and relation to sexual practices. AIDS Care. 1998;10:599–610. doi: 10.1080/09540129848451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zea MC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Echeverry JJ, Bianchi FT. Disclosure of HIV-positive status to Latino gay men’s social networks. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(1–2):107–116. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014322.33616.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]