Abstract

Ureaplasma species, the most commonly isolated microorganisms in women with chorioamnionitis, are associated with preterm delivery. Chorioamnionitis increases the risk and severity of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and persistent pulmonary hypertension in newborns. It is not known whether the timing of exposure to inflammation in utero is an important contributor to the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. We hypothesized that chronic inflammation would alter the pulmonary air space and vascular development after 70 days of exposure to infection. Pregnant ewes were given intra-amniotic injection of Ureaplasma parvum serovars 3 or 6 at low (2 × 104 cfu) or high doses (2 × 107 cfu) or media (controls) at 55 days gestational age. Fetuses were delivered at 125 days (term = 150 days). U. parvum was grown from the lungs of all exposed fetuses, and neutrophils and monocytes were increased in the air spaces. Lung mRNA expression of IL-1β and IL-8, but not IL-6, was modestly increased in U. parvum-exposed fetuses. U. parvum exposure increased surfactant and improved lung gas volumes. The changes in lung inflammation and maturation were independent of serovar or dose. Exposure to U. parvum did not change multiple indices of air space or vascular development. Parenchymal elastin and collagen content were similar between groups. Expression of several endothelial proteins and pulmonary resistance arteriolar media thickness were also not different between groups. We conclude that chronic exposure to U. parvum does not cause sustained effects on air space or vascular development in premature lambs.

Keywords: chorioamnionitis, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, fetal inflammatory response syndrome

intrauterine inflammation identified as clinical or histological chorioamnionitis is associated with preterm labor, delivery, and increased risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality (9). Ureaplasmas are common colonizers of the male and female lower genitourinary tracts and are the microorganisms most frequently associated with preterm birth (37, 38, 46, 48). Approximately 12% of amniotic fluids collected by routine amniocentesis from asymptomatic pregnancies at 15–20 wk of gestation tested positive for Ureaplasma species (8, 35), and colonization was higher (44–58%) in amniotic fluid from preterm deliveries or pregnancies complicated by preterm prelabor with rupture of membranes (8, 52).

Epidemiological studies suggest that inflammation or infection in utero increases the risk and the severity of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) (42, 43); Ureaplasma colonization may contribute to the etiology of these diseases (37, 38, 46, 48). It is not known whether the timing of the exposure modulates the complications of prematurity. Indeed, exposures to microorganisms may be initiated as early as the time of conception because mycoplasmas are detected in 22–35% of sperm samples used by assisted reproductive clinics (29).

Acute exposure to intra-amniotic LPS causes significant alterations to pulmonary air space and vascular development within days. Intra-amniotic injection of LPS results in larger, fewer alveoli, and reduced secondary septation in the fetal lungs, consistent with human studies of infants with BPD (12, 31, 51). Furthermore, intra-amniotic LPS results in decreased pulmonary endothelial cell protein expression followed by vascular remodeling, as demonstrated by smooth muscle hypertrophy and increased adventitial collagen deposition in pulmonary resistance arterioles (14). These vascular changes in response to intra-amniotic LPS in sheep suggest that similar effects may be responsible for the increased risk of PPHN in newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis. However, the role of antenatal exposure to microorganisms, such as Ureaplasma in the pathogenesis of aberrant lung development in the preterm, has not been systematically investigated.

The previously described 14 serovars (and 2 biovars) of U. urealyticum are now classified into two separate species: U. parvum (serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14) and U. urealyticum (serovars 2, 4, 5, 7–13). The virulence of these separate serovars of the Ureaplasma spp. may be different (20). Whether the size of the initial inoculum is a determinant of virulence is also not known. Previously, we demonstrated that intra-amniotic injection of U. parvum serovar 3 and U. parvum serovar 6 (2 × 107 cfu) in sheep at midgestation caused histological chorioamnionitis, fetal pulmonary colonization and inflammation, and lung maturation 6 wk after injection (30, 32). Given the associations of aberrant pulmonary angiogenesis with abnormal alveolar growth, pulmonary hypertension complicating the course of BPD in some preterm infants (44), and inflammation in utero being associated with increased risk and severity of BPD, we investigated the effects of early and chronic exposure to Ureaplasma in utero on pulmonary air space and vascular development. We used U. parvum serovars 3 and 6 for the present studies since these serovars were the most prevalent Ureaplasma spp. isolated from women who delivered preterm (20). We hypothesized that exposure to U. parvum serovars 3 or 6 from early gestation causes a sustained inflammatory response and persistent adverse consequences on pulmonary air space and vascular development. We also investigated whether the initial inoculum size of U. parvum serovars 3 vs. 6 influenced fetal lung development.

METHODS

The animal studies were performed in Western Australia with date-mated Merino ewes with singleton gestations. All studies were approved by the animal ethics committees of the University of Western Australia and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

Prenatal Treatment

Low passage Ureaplasmas were prepared for injection using first passage (P1) and P2 Ureaplasmas and stored at −80°C. Before injection, the U. parvum was thawed and diluted in sterile cold PBS in injection volumes of 2 ml. Inoculates were mixed, kept on ice, and warmed immediately before injection. The controls received injections using the same volume of culture media diluted in PBS. At 55 days of gestation, ewes were allocated at random to intra-amniotic injections of one of five treatments: media only (n = 7), low-dose (LD; 2 × 104 cfu) U. parvum serovar 3 (S3LD; n = 6) or serovar 6 (S6LD; n = 8), or high-dose (HD) (2 × 107 cfu) U. parvum serovar 3 (S3HD; n = 7) or serovar 6 (S6HD; n = 8). The intra-amniotic injections were performed with ultrasound guidance and verified by electrolyte analysis of amniotic fluid (13).

Delivery and Postmortem Tissue Collection

Ewes at 125 days (term is 150 days) were anesthetized with an IV injection of ketamine (10 mg/kg; Parnell Labs, New South Wales, Australia) and medetomidine (0.1 mg/kg, 2 min; Domitor, Pfizer Animal Health, New South Wales, Australia) and then received spinal anesthesia (2% lidocaine; 60 mg) before delivery of fetuses. An umbilical arterial blood sample was collected, and the fetus was then killed with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) injected into an umbilical vein. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected by instilling physiological saline into the left lung to total lung capacity followed by withdrawal, with the procedure being repeated three times (13). Pooled BALF was used for cell counts and saturated phosphatidylcholine measurement. BALF cell counts were expressed as total cells recovered from the lavage normalized to body weight. Pieces of right lower lobe of lung were snap-frozen for RNA and protein analysis. The right upper lobe of lung was inflation fixed in 10% buffered formalin at 30 cmH2O pressure and serially sectioned, and three pieces were randomly selected for morphology (5).

RNA and Protein Assessments

Lung expression of cytokine mRNAs IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, and vascular protein mRNAs VEGF-165, VEGF-188, PECAM-1, and Tie-1 were measured by RNase protection analyses using 10 μg of total lung RNA, as described previously (14, 18). The protected fragments were resolved on 6% polyacrylamide (8 mol/l urea) gels, visualized by autoradiography, quantified on a PhosphorImager using ImageQuant software (v1.2; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA), and normalized to the abundance of ribosomal protein mRNA L32. Fifty micrograms of total lung protein were used for Western immunoblot measurement of VEGFR2, NOSIII (eNOS), and Tie-2 proteins (14). The following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-eNOS antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Tie-2 antibody (sc-324), or rabbit polyclonal anti-VEGF-R2 antibody (sc-504; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The densitometry values from autoradiographs were normalized to β-actin by stripping the membrane and probing with an anti-β-actin antibody (Seven Hills Bioreagents, Cincinnati, OH) using ImageQuant. IL-8 protein in BALF was measured by ELISA using sheep-specific antibodies (16).

Immunohistochemistry for α-Smooth Muscle Actin, VEGF Receptor-2, and Myeloperoxidase

The immunostaining methods were performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (14). Antigen retrieval was performed using citrate buffer, pH 6.0, boiled and pretreated with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide to destroy endogenous peroxidase. Sections were incubated with anti-α-smooth muscle actin (1:5,000; Sigma, cat. no. 5228), VEGF receptor-2 (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA; cat. no. 2479, 1:50), or anti-myeloperoxidase (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA; cat. no. CMC028, 1:400) at 4°C overnight followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. Nonspecific interactions were inhibited by using 2% goat serum during both primary and secondary antibody incubation. Immunostaining was visualized by the Vectastain ABC peroxidase Elite kit to detect the antigen-antibody complexes (Vector Laboratories) and developed using diaminobenzidine and cobalt. The nuclei were counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red.

Collagen and Elastin Content

To evaluate the morphological changes in the pulmonary vessels and the air spaces differentially, parenchymal collagen and elastin content were estimated from Massons Trichrome Blue and Miller's stained sections, which selectively stain collagen and elastin, respectively. Digitized images from 10 non-overlapping parenchymal fields were captured from each 5-μm section and examined at a magnification of ×950. Elastin and collagen staining density was measured (Image Pro Plus v4.5; Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). For each field of view, staining density was expressed relative to the tissue area. Adventitial fibrosis was evaluated by Massons Trichrome staining. Ten arterioles per lamb with measurements of ≤50 μm external diameter, accompanying the terminal bronchioles, were scored for collagen staining (14). A qualitative scoring system was used to evaluate adventitial fibrosis: score 0 = none, score 1 = mild, score 2 = moderate, and score 3 = severe. All histological measurements were conducted by an investigator (R. G. B. Dalton) blinded to the study groups.

Air Space and Vascular Morphometry

Air spaces.

The morphometric measurements were performed in a blinded fashion. Five-micrometer sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and 10 non-overlapping parenchymal fields were captured for morphometric measurements. Mean linear intercepts were determined by counting the number of points that fell on air space and on alveolar septal tissue and the number of air/tissue tissue/air intercepts on digital superimposition of a linear point counting grid (36 lines/72 points) (36). Alveolar secondary crests were identified by elastin staining using Miller's staining procedure. The alveolar secondary crest volume density was estimated by point counting, using a 494-point coherent square lattice, and expressed in relation to parencyhmal tissue volume density. Five non-overlapping, calibrated fields were analyzed in two random tissue sections per lamb.

Vascular.

Measurements of arteriolar wall thickness were made using α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) immunostaining to demarcate the medial layer. Ten arterioles per lamb with measurements of ≤50 μm external diameter accompanying the terminal bronchioles (identified by morphological criteria) were measured. Only transversely sectioned airways were evaluated to minimize distortion of arteriolar media. Morphometric measurements included thickness of the arteriolar media, external vessel diameter, external vessel area, and area of smooth muscle (vessel lumen external area minus internal area) and were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus on digitally acquired images. The wall thickness was expressed as [(2·medial wall thickness)/(external diameter)]·100. All morphometric assessments were performed on the right upper lobe to account for regional maturation variability known to exist within the lungs (19, 21) and were assessed by a single observer (R. G. B. Dalton) blinded to the experimental group.

Evaluation of Lung Maturation

Surfactant lipids and lung compliance were measured to evaluate lung maturation. Saturated phosphatidylcholine (Sat PC) was isolated from chloroform-methanol (2:1) extracts of BALF by neutral alumina column chromatography after exposure of lipid extracts to osmium tetroxide (27). Sat PC was quantified by phosphorus assay (4, 27). Lung compliance was evaluated by measuring the deflation limb of a pressure-volume curve with the chest open (18).

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as means ± SE. Ureaplasma-exposed and media control groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance. Comparison between two groups was made using a Mann-Whitney non-parametric t-test. The rank sum test was used for non-parametric distributions if normality could not be obtained by data transformation. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Pulmonary Inflammation

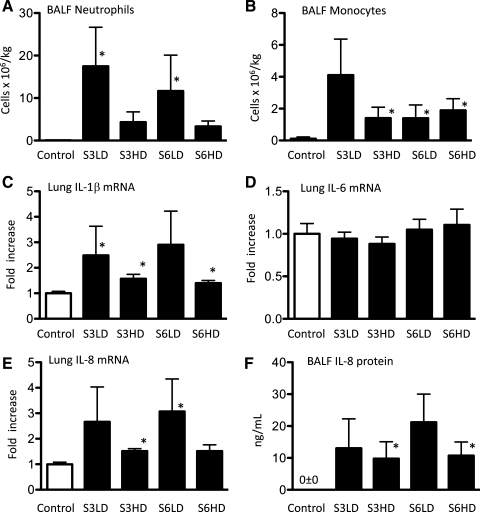

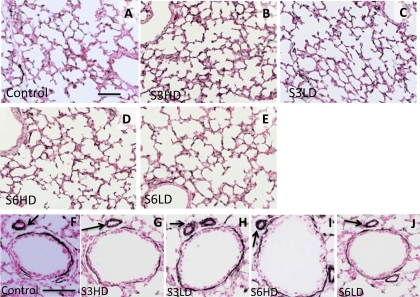

Colonization of lung tissue with U. parvum was confirmed in all Ureaplasma-exposed lambs (average 2.9 × 106 cfu/ml: range 2.8 × 105 - 2.8 × 107 cfu/ml). Colonization was not detected in media controls. BALF neutrophil and monocyte counts (Fig. 1, A and B) were low in media control lambs (<105/kg body wt). The low-dose U. parvum exposures (serovar 3 and 6) recruited ∼15 × 106 neutrophils/kg to the air spaces; counts were somewhat lower after high-dose U. parvum exposure. Airway monocyte numbers also increased following the U. parvum exposures. The mRNA for the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-8 was induced up to threefold by the U. parvum exposures compared with media controls, but IL-6 mRNA expression did not change (Fig. 1, C–E). IL-8 protein in BALF was not detected in controls (Fig. 1F); consistent with the mRNA data, U. parvum exposures increased BALF IL-8 protein levels to 10–20 ng/ml. Immunostaining with myeloperoxidase (MPO) was performed for morphological visualization of activated inflammatory cells in the lung. Control lambs had no MPO expression (Fig. 2A), whereas the lambs exposed to the different serovars and doses of Ureaplasmas had MPO-positive cells both in the air space lumen and in the lung parenchyma (Fig. 2, B–E). Consistent with the BALF neutrophil cell count data, there appeared to be more MPO-positive cells in the low-dose vs. the high-dose group. However, there were significant variabilities in the inflammatory markers within each subgroup, and different inflammatory marker expressions were largely independent of either the serovar or dose of Ureaplasmas.

Fig. 1.

Ureaplasma exposure induces modest lung inflammation. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) neutrophils (A) and monocytes (B) expressed per kilogram of body weight. Quantification of IL-1β (C), IL-6 (D), and IL-8 (E) mRNA from fetal lung, normalized to L32 (ribosomal protein mRNA) by an RNase protection assay using 10 μg of total lung RNA. F: BALF IL-8 protein levels measured by ELISA. For the RNA measurements, the mean mRNA signal in control animals was given the value of 1, and levels in each animal were expressed relative to controls (n = 6–8/group, *P < 0.05 vs. media controls).

Fig. 2.

Lung inflammation and histology after Ureaplasma exposure. Immunostaining with myeloperoxidase (MPO) using representative sections from control (A), high-dose U. parvum serovar 3 (S3HD) (B), low-dose U. parvum serovar 3 (S3LD) (C), high-dose U. parvum serovar 6 (S6HD) (D), and low-dose U. parvum serovar 6 (S6LD) (E). No MPO-positive cells were seen in the control group. There were variable numbers of MPO-positive cells (arrows) in the different Ureaplasma-exposed groups. The lung architecture was similar across the groups. The higher magnification in the insets show inflammatory cells. Scale bar = 50 μm.

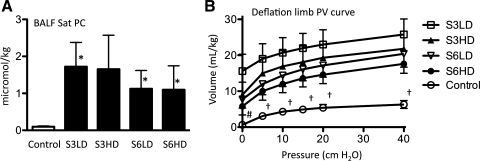

Lung Maturation

Sat PC pool size was 0.1 ± 0.02 μmol/kg body wt in controls (Fig. 3A). Exposure to U. parvum increased the airway Sat PC pool size 11- to 17-fold in the different groups. Lung compliance, as measured by deflation limb pressure-volume curve, also improved three- to fourfold for the U. parvum exposure groups (Fig. 3B). There was considerable variability in the Sat PC and pressure-volume curve measurements of U. parvum-exposed lambs. Lung compliance tended to be higher in the serovar 3 groups than the serovar 6 groups, and was qualitatively higher in the low-dose groups than in the high-dose groups.

Fig. 3.

Ureaplasma exposure causes lung maturation. A: BALF surfactant-saturated phosphatidylcholine (Sat PC) expressed per kilogram of body weight. B: deflation limb pressure-volume (PV) curve. N = 6–8/group, *P < 0.05 vs. media controls, †P < 0.05 control vs. all U. parvum groups, #P < 0.05 control vs. S3LD only.

Pulmonary Vascular Development and Arteriolar Morphometry

In U. parvum-exposed sheep fetuses, VEGF isoforms 165 or 188 mRNA expression or the VEGFR2 protein abundance were not different compared with media controls (Fig. 4, A and B). Similarly, the expression of other vascular endothelial proteins, NOSIII (eNOS) and Tie-2, and the mRNA expression of PECAM-1 and Tie-1, were also not different between media controls and U. parvum-exposed lambs, regardless of serovar or dose (Fig. 4, C–F). VEGFR2 was expressed in the small and large vessel endothelium in the lung. There were no qualitative differences between the densities of pulmonary microvasculature between the Ureaplasma-exposed groups vs. the media control as revealed by VEGFR2 immunostaining (Fig. 5, A–E).

Fig. 4.

Ureaplasma exposure does not change the expression of pulmonary vascular proteins. Quantification of VEGF 165 and VEGF 188 isoform mRNA (A), VEGFR2 protein (B), PECAM-1 mRNA (C), NOSIII (eNOS) protein (D), Tie-1 mRNA (E), and Tie-2 protein (F). The quantitation of mRNA was normalized to L32 (ribosomal protein mRNA) and performed by a RNase protection assay using 10 μg of total lung RNA. The mean mRNA signal in control animals was given the value of 1, and levels in each animal were expressed relative to controls. The protein levels were measured by Western blotting using 50 μg of protein from lung homogenate (n = 4–7/group).

Fig. 5.

Ureaplasma exposure does not change pulmonary capillary density and arteriolar smooth muscle thickness. Immunostaining with VEGFR2 using representative sections from control (A), S3HD (B), S3LD (C), S6HD (D), and S6LD (E). VEGFR2 stained the small and large pulmonary vascular endothelium. There were no differences between the groups in the qualitative density of VEGFR2 expression. Immunostaining with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) using lung sections from control (F), S3HD (G), S3LD (H), S6HD (I), and S6LD (J). Sections show a bronchiole with a resistance arteriole (arrows). The smooth muscle thickness demarcated by α-SMA was similar across groups. Scale bar = 50 μm.

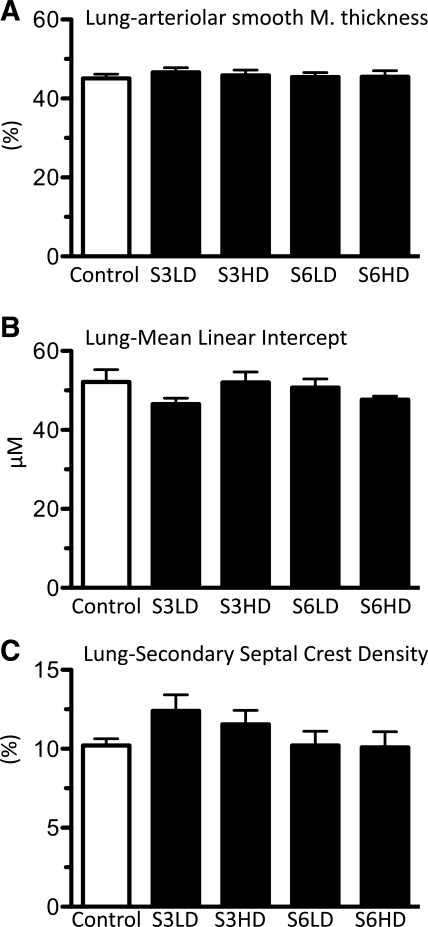

Arteriolar smooth muscle thickness was evaluated by α-SMA staining of the arteriolar medial layer (Fig. 5, F–J). Morphometric evaluation of the thickness of resistance arterioles was consistent with the qualitative assessment, and the measurements were not different between media controls and any of the U. parvum-exposed groups (Fig. 6A). Smooth muscle wall thickness, as determined by the area occupied by smooth muscle/total arteriolar area, was also not different between media controls or U. parvum groups (Table 1). Adventitial fibrosis score was not different between media controls and U. parvum-exposed groups (Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Ureaplasma exposure does not alter lung air space and vascular development. A: quantification of the thickness of pulmonary arteriolar smooth muscle (expressed as % of external diameter) in resistance arterioles (<50 μm). Alveolar development was quantified by measuring mean linear intercept (B) or alveolar secondary septal crest density (C). Morphometric measurements were performed in a blinded fashion (n = 4–6/group).

Table 1.

Pulmonary vascular morphometry

| Media | S3LD | S3HD | S6LD | S6HD | All UP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arteriolar Media Thickness (μm) | 7.25 ± 0.22 | 7.83 ± 0.14 | 7.77 ± 0.12 | 7.30 ± 0.12 | 7.26 ± 0.17 | 7.54 ± 0.14 |

| Muscle area/total area (%) | 70.0 ± 0.7 | 71.1 ± 0.6 | 70.6 ± 0.7 | 70.7 ± 0.5 | 69.7 ± 0.7 | 70.8 ± 0.6 |

| Adventitial fibrosis score | 1.07 ± 0.43 | 1.31 ± 0.29 | 1.46 ± 0.57 | 1.33 ± 0.51 | 1.15 ± 0.37 | 1.31 ± 0.09 |

Data are expressed as means ± SE. S3 or S6, serovar 3 or serovar 6; LD, low dose; HD, high dose, All UP, pooled animals from the 4 Ureaplasma parvum groups.

Air Space Development

Morphometry.

Mean linear intercept is a commonly used measure of alveolar development and is inversely proportional to alveolarization. The mean linear intercept was the same across controls and gestation-matched U. parvum-exposed preterm sheep fetuses (Fig. 6B). Compared with the mean linear intercept, measurement of the alveolar secondary septation is less susceptible to lung volume-related changes. The volume of the secondary septal crest relative to tissue parenchymal volume was not different across the groups (Fig. 6C). Alveolar wall thickness, air space volume fraction, and tissue volume fraction were also not different between U. parvum and media controls, regardless of the serovar or dose (Table 2).

Table 2.

Airway and lung parenchymal morphometry

| Media | S3LD | S3HD | S6LD | S6HD | All UP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface fraction | 77.4 ± 4.3 | 86.4 ± 2.9 | 77.8 ± 3.8 | 79.6 ± 3.5 | 84.0 ± 1.6 | 81.9 ± 1.6 |

| Alveolar wall thickness (μm) | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.02 |

| Air space volume fraction (%) | 50.6 ± 3.9 | 57.4 ± 2.3 | 57.2 ± 3.5 | 57.1 ± 2.1 | 58.8 ± 1.6 | 57.6 ± 1.2 |

| Tissue volume fraction (%) | 49.4 ± 3.8 | 42.6 ± 2.3 | 42.8 ± 3.5 | 42.9 ± 2.1 | 41.2 ± 1.6 | 42.4 ± 0.01 |

| Elastin content (% of tissue) | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 7.1 ± 3.4 | 5.8 ± 0.6 |

Data are expressed as means ± SE.

Collagen and elastin staining.

Changes in collagen and elastin are hallmarks of chronic lung diseases of preterm infants (46). A semiquantitative measurement of total elastin content (expressed as staining intensity per high powered field) was not different between the groups (Table 2). Parenchymal elastin distribution was mainly confined to alveolar secondary septa, and to some extent the pleura, and was not abnormally localized in either the controls or the U. parvum-exposed animals (data not shown). There was minimal parenchymal collagen deposition, with expression predominately around airway walls, and, to some extent, alveolar septa (data not shown).

Variability in fetal responses to U. parvum.

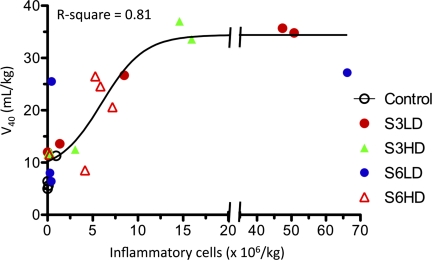

We performed regression analysis to determine the impact of variability in fetal inflammatory responses on lung maturation and lung morphometry. Lung inflammation, defined as numbers of airway neutrophils plus monocytes per kilogram, did not correlate with U. parvum titers in lung tissue collected at delivery (data not shown). In contrast, there was a dose-response-with-saturation relationship between lung inflammation, lung compliance (Fig. 7), and saturated phosphatidylcholine (data not shown). There was a modest linear correlation between lung inflammation and arteriolar smooth muscle thickness (R-squared = 0.22, P = 0.04). However, there was no correlation between lung inflammation and multiple indicators of air space and vascular morphometry (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Dose-response relationship between lung volume and lung inflammation. A best-fit curve was determined by regression analysis with variables of bronchoalveolar lavage cell counts (neutrophils + monocytes) expressed as per kilogram of body weight and lung volume at 40 cmH2O pressure (V40) expressed as per kilogram of body weight. The control animals and those in the different U. parvum subgroups are indicated by different symbols.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the pulmonary effects of chronic fetal exposure to different U. parvum serovars, important perinatal pathogens, in parallel with studies to determine the virulence factors for U. parvum (unpublished observations). Ureaplasmas colonized the immature sheep fetuses, because large numbers of U. parvum were cultured from amniotic fluid, the chorioamnion, and the fetal lungs. The fetuses responded to U. parvum since lung inflammation and maturation occurred in U. parvum-exposed preterm lambs but not the media controls. Approximately 10% of the pregnancies exposed to U. parvum were lost during the study, but this rate was no different from media-exposed controls or the usual frequency of pregnancy losses in sheep. The remarkable finding in this study was that, despite high chronic U. parvum colonization for the 70-day interval from exposure to delivery, no changes in long-term alveolar or vascular morphometry, or the expression of vascular endothelial proteins, were detected. Neither the dose of initial inoculums nor the different serovars tested had any effect on the lung structure.

There is a considerable interest in evaluating how host responses determine fetal lung inflammatory responses to Ureaplasma. Our group has previously characterized some effects of intrauterine U. parvum serovars 3 and 6 in pregnant sheep (30, 32). Intra-amniotic injection of U. parvum at 80 days (midgestation) results in histological chorioamnionitis and modest fetal lung inflammation 6 wk after exposures. Fetal lung inflammation persisted for 9–10 wk when fetal sheep were exposed to U. parvum in midgestation (30). Non-human primates exposed to U. parvum for a short interval at midgestation mount a vigorous lung inflammatory response (34). The results from our current study demonstrate that the early-gestation sheep fetus can also mount an inflammatory response to U. parvum, although there appears to be species differences in host response.

Another variable in the magnitude of lung inflammation is the duration after exposure to U. parvum. Recent studies in fetal or adult mice exposed to U. parvum demonstrate a self-limiting lung inflammatory response (7, 33). In non-human primate fetuses, Novy and colleagues (34) reported that the acute inflammatory response partially resolved at >10 days after ureaplasmal or mycoplasmal infection; epithelial hyperplasia of terminal airways and thickened alveolar walls remained. We found little evidence of parenchymal damage or sustained bronchiolitis in U. parvum-exposed fetal lungs in contrast to the non-human primate models (34, 49).

There are significant differences between lung inflammatory responses to intra-amniotic exposures to LPS vs. U. parvum. The recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the fetal air spaces and induction of IL-1β in the lung from U. parvum infection is ∼1–2 log orders lower than that induced by LPS (18, 30, 32). LPS signals via the TLR4 receptor, whereas U. parvum signaling is mediated via interactions with TLR1, 2, and 6 (39). We have previously demonstrated that lung inflammatory response to TLR4 agonists is much more robust than responses to either a TLR2 or TLR3 agonist in the fetal sheep (11). The demonstration in this study that an early-gestation sheep fetus can mount an inflammatory response to pathogens is interesting since the pulmonary expression of TLRs is known to be developmentally regulated in multiple species (3, 10, 11).

The hallmarks of BPD in preterm infants are altered lung development and lung inflammation (41). In preterm fetal baboons given an intra-amniotic injection of Ureaplasmas 2 days before delivery, approximately one-half of the baboons had persistent postnatal colonization. The Ureaplasma-infected lungs had more extensive fibrosis and increased myofibroblast phenotype and TGF-β1 staining (53). In human autopsy studies, smooth muscle α staining and TGF-β1 immunostaining were greater in Ureaplasma pneumonia-associated cases of BPD compared with other cases (46). However, fetal mice given intra-amniotic injection of Ureaplasmas did not have alveolar simplification assessed postnatally (33). In this study, alveolar wall thickness and volume, parenchymal collagen, α-SMA staining, and elastin distribution and content in the pulmonary vessels or the air spaces were not different from controls after 70 days of exposure to U. parvum serovars 3 or 6 in utero. These results contrast with the effects of exposure to LPS in fetal sheep; intra-amniotic LPS either 7 days after a single injection, or after 28 days via a continuous Alzet pump, caused increased average alveolar volume, decreased total alveolar number, and thinner alveolar wall thickness (31, 51). However, aberrant lung development caused by midgestation exposure to a 28-day infusion of LPS was not sustained when the lung morphology was assessed near term gestation (17). Preterm fetuses exposed to multiple doses of intra-amniotic LPS develop endotoxin tolerance (15). Whether fetuses exposed continuously to live U. parvum also develop tolerance is not known. Together, these results suggest that the preterm fetus exposed to proinflammatory stimuli in utero have a self-limiting lung injury response. The precise mechanisms as to how the fetus is able to downregulate injury responses or invoke repair mechanisms remain to be studied.

Abnormal pulmonary vascular development is an important component of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (1). In vitro studies have shown that U. urealyticum antigen can stimulate human macrophages to produce VEGF and soluble ICAM-1, factors previously shown to be expressed in infants developing BPD (22, 24, 26). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of chronic intrauterine U. parvum exposure on pulmonary vascular development. We measured the expression of proteins known to be important in vascular development. Because of the limited availability of reagents in the sheep, parallel measurements to evaluate changes in mRNA and the cognate protein could not be performed in most cases. It is possible that some molecules change at the gene expression level, but protein estimates are similar, or other proteins are posttranslationally modified, and the gene expression levels may not change. Despite these limitations, chronic exposure to early-gestation U. parvum did not change the expression of several endothelial proteins measured at 125 days of gestation. Similarly, there were no changes in resistance arteriolar medial thickness or adventitial collagen content, correlates of pulmonary hypertension. The lack of changes in vascular protein expression and morphometry after exposure to U. parvum are in contrast to effects induced by intra-amniotic exposure to LPS. We previously showed that exposure to LPS in utero caused significant reductions in eNOS, VEGF 165, and VEGF 188, PECAM-1, Tie-2 and VEGFR2 protein expression in the lungs, and caused arteriolar smooth muscle hypertrophy and adventitial fibrosis in preterm fetal lambs (14).

In the present study, fetal responses to U. parvum were quite variable even within the subgroups. Interestingly, lung inflammation assessed by inflammatory cell recruitment did not correlate with the U. parvum titers. In contrast, lung maturation exhibited a dose-response and saturation relationship with lung inflammation. Although increased lung surfactant pools are a major contributor to improved lung function in Ureaplasma-exposed fetuses compared with media controls, other possibilities, including changes in the lung fluids, were not evaluated. The variability of fetal inflammatory response could have masked lung morphological changes. However, upon regression analysis, there was no relationship between lung inflammation and multiple indices of air space and vascular morphometry, with a possible exception of a modest correlation with arteriolar smooth muscle thickness. Furthermore, when results for all the Ureaplasma-exposed animals were pooled and compared with controls, there were no differences in morphometric measurements. These results make it unlikely that a significant lung injury response induced by U. parvum in the fetus was missed. Similarly, the present experiments also suggest that altered lung structure was not a significant contributor to improved lung function in the U. parvum-exposed fetuses. The causes of inter-animal variability in lung inflammatory response exposed to the same U. parvum titer may relate to complex host-pathogen relationships that need further investigation.

There are some differences between our model and human chorioamnionitis. Gerber et al. (8) identified ∼11% of amniotic fluid samples obtained between 15 and 17 wk from asymptomatic women who were positive for Ureaplasma species. Of these, ∼58% of women with positive amniotic fluid for Ureaplasma went into preterm labor, and 24% had preterm deliveries. Although the amniotic fluid was colonized with Ureaplasma in our study, the ewes did not have preterm labor. In contrast to the present study, rhesus monkeys injected with U. parvum had a 100% rate of preterm deliveries (34). Delivery of Ureaplasma species in the respiratory tract or the amniotic fluid induced acute bronchiolitis in preterm baboons (49) and interstitial pneumonia in adult mice (6). Intra-amniotic injection of Ureaplasma species in primates caused acute inflammation in the respiratory tract followed by peribronchial lymphoid aggregates and hyperplastic changes in the epithelium (34). In contrast to these reports in the non-human primates, there was a minimal lung inflammatory response in the fetal sheep exposed to high titers of U. parvum. While the reasons for discrepancies in lung inflammation and morphology in these different experiments are not clear, the possibilities include species differences and the variable time of exposure to Ureaplasma.

There is considerable controversy regarding the role of U. parvum in the pathogenesis of human BPD (28). While some studies have associated exposure to chorioamnionitis with BPD (47, 50), other recent reports have failed to document associations between chorioamnionitis and BPD (2, 23, 25, 40, 45). Discrepancies among these studies may be related to different patient populations, different organisms, and different periods of exposures to microorganisms among other factors. Both midgestation and early-gestation fetal sheep can respond to U. parvum with modest inflammatory responses. However, injury responses seen after acute exposures may resolve with chronic exposures to intrauterine proinflammatory agents (17, 31). The present study examined the effects of antenatal exposure to U. parvum alone, whereas infants may have exposures to several different proinflammatory stimuli both antenatally and postnatally. Indeed, studies in mice and baboons suggest that antenatal Ureaplasma exposures potentiate responses to postnatal inflammatory stimuli such as oxygen and mechanical ventilation (33, 53). The increase in injury response with “multiple hits” (chorioamnionitis and mechanical ventilation) has also been documented in preterm infants (45).

In conclusion, chronic colonization of the amniotic cavity by U. parvum in pregnant ewes, arising early in gestation, does not result in long-term molecular or morphometric changes in the fetal lung.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; Grant 458576 and CDA 303261), the Women and Infants Research Foundation, a National Heart Foundation of Australia and NHMRC Fellowship (G. R. Polglase), and National Institutes of Health Grants HD-57869 (S. G. Kallapur) and HL-97064 (A. H. Jobe and S. G. Kallapur).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of JRL Hall & Company, Ross Wales, Sarah Ritchie, and Fiona Hall for the supply and care of the sheep and to Amy Whitescarver and Manny Alvarez, Jr., for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia - “a vascular hypothesis”. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 1755–1756, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Faye-Petersen O, Cliver S, Goepfert AR, Hauth JC. The Alabama Preterm Birth study: polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cell placental infiltrations, other markers of inflammation, and outcomes in 23- to 32-week preterm newborn infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195: 803–808, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awasthi S, Cropper J, Brown KM. Developmental expression of Toll-like receptors-2 and -4 in preterm baboon lung. Dev Comp Immunol 32: 1088–1098, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett GR. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J Biol Chem 234: 466–468, 1959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolender RP, Hyde DM, Dehoff RT. Lung morphometry: a new generation of tools and experiments for organ, tissue, cell, and molecular biology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 265: L521–L548, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crouse DT, Cassell GH, Waites KB, Foster JM, Cassady G. Hyperoxia potentiates Ureaplasma urealyticum pneumonia in newborn mice. Infect Immun 58: 3487–3493, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Famuyide ME, Hasday JD, Carter HC, Chesko KL, He JR, Viscardi RM. Surfactant protein-A limits Ureaplasma-mediated lung inflammation in a murine pneumonia model. Pediatr Res 66: 162–167, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber S, Vial Y, Hohlfeld P, Witkin SS. Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in second-trimester amniotic fluid by polymerase chain reaction correlates with subsequent preterm labor and delivery. J Infect Dis 187: 518–521, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med 342: 1500–1507, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harju K, Glumoff V, Hallman M. Ontogeny of Toll-like receptors Tlr2 and Tlr4 in mice. Pediatr Res 49: 81–83, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillman NH, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Kramer BW, Bachurski CJ, Ikegami M, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Toll-like receptors and agonist responses in the developing fetal sheep lung. Pediatr Res 63: 388–393, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husain AN. Pathology of arrested acinar development in postsurfactant bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Hum Pathol 29: 710–717, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jobe AH, Newnham JP, Willet KE, Moss TJ, Ervin MG, Padbury JF, Sly PD, Ikegami M. Endotoxin-induced lung maturation in preterm lambs is not mediated by cortisol. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1656–1661, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kallapur SG, Bachurski CJ, Le Cras TD, Joshi SN, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Vascular changes after intra-amniotic endotoxin in preterm lamb lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L1178–L1185, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kallapur SG, Jobe AH, Ball MK, Nitsos I, Moss TJ, Hillman NH, Newnham JP, Kramer BW. Pulmonary and systemic endotoxin tolerance in preterm fetal sheep exposed to chorioamnionitis. J Immunol 179: 8491–8499, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kallapur SG, Moss TJ, Auten RL, Jr, Nitsos I, Pillow JJ, Kramer BW, Maeda DY, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. IL-8 signaling does not mediate intra-amniotic LPS-induced inflammation and maturation in preterm fetal lamb lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L512–L519, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallapur SG, Nitsos I, Moss TJM, Kramer BW, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Chronic endotoxin exposure does not cause sustained structural abnormalities in the fetal sheep lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L966–L974, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallapur SG, Willet KE, Jobe AH, Ikegami M, Bachurski CJ. Intra-amniotic endotoxin: chorioamnionitis precedes lung maturation in preterm lambs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L527–L536, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendall JZ, Lakritz J, Plopper CG, Richards GE, Randall GC, Nagamani M, Weir AJ. The effects of hydrocortisone on lung structure in fetal lambs. J Dev Physiol 13: 165–172, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knox CL, Timms P. Comparison of PCR, nested PCR, and random amplified polymorphic DNA PCR for detection and typing of Ureaplasma urealyticum in specimens from pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol 36: 3032–3039, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotas RV, Kling OR, Block MF, Soodsma JF, Harlow RD, Crosby WM. Response of immature baboon fetal lung to intra-amniotic betamethasone. Am J Obstet Gynecol 130: 712–717, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotecha S, Chan B, Azam N, Silverman M, Shaw R. Increase in interleukin-8 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from premature infants who develop chronic lung disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 72: F90–F96, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lahra MM, Beeby PJ, Jeffery HE. Intrauterine inflammation, neonatal sepsis, and chronic lung disease: a 13-year hospital cohort study. Pediatrics 123: 1314–1319, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lassus P, Turanlahti M, Heikkila P, Andersson LC, Nupponen I, Sarnesto A, Andersson S. Pulmonary vascular endothelial growth factor and Flt-1 in fetuses, in acute and chronic lung disease, and in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 1981–1987, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laughon M, Allred EN, Bose C, O'Shea TM, Van Marter LJ, Ehrenkranz RA, Leviton A. Patterns of respiratory disease during the first 2 postnatal weeks in extremely premature infants. Pediatrics 123: 1124–1131, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li YH, Brauner A, Jensen JS, Tullus K. Induction of human macrophage vascular endothelial growth factor and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by Ureaplasma urealyticum and downregulation by steroids. Biol Neonate 82: 22–28, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mason R, Nellenbogen J, Clements J. Isolation of disaturated phosphatidylcholine with osmium tetroxide. J Lipid Res 17: 281–284, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxwell NC, Nuttall D, Kotecha S. Does Ureaplasma spp. cause chronic lung disease of prematurity: ask the audience? Early Hum Dev 85: 291–296, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montagut JM, Lepretre S, Degoy J, Rousseau M. Ureaplasma in semen and IVF. Hum Reprod 6: 727–729, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss TJ, Knox CL, Kallapur SG, Nitsos I, Theodoropoulos C, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Experimental amniotic fluid infection in sheep: effects of Ureaplasma parvum serovars 3 and 6 on preterm or term fetal sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 198: 122e121–e128, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss TJ, Newnham JP, Willett KE, Kramer BW, Jobe AH, Ikegami M. Early gestational intra-amniotic endotoxin: lung function, surfactant, and morphometry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 805–811, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Knox CL, Polglase GR, Kallapur SG, Ikegami M, Jobe AH, Newnham JP. Ureaplasma colonization of amniotic fluid and efficacy of antenatal corticosteroids for preterm lung maturation in sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200: 96e91–e96, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Normann E, Lacaze-Masmonteil T, Eaton F, Schwendimann L, Gressens P, Thebaud B. A novel mouse model of Ureaplasma-induced perinatal inflammation: effects on lung and brain injury. Pediatr Res 65: 430–436, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novy MJ, Duffy L, Axthelm MK, Sadowsky DW, Witkin SS, Gravett MG, Cassell GH, Waites KB. Ureaplasma parvum or Mycoplasma hominis as sole pathogens cause chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, and fetal pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Reprod Sci 16: 56–70, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perni SC, Vardhana S, Korneeva I, Tuttle SL, Paraskevas LR, Chasen ST, Kalish RB, Witkin SS. Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in midtrimester amniotic fluid: association with amniotic fluid cytokine levels and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191: 1382–1386, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Jobe AH, Newnham JP, Moss TJ. Maternal and intra-amniotic corticosteroid effects on lung morphometry in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res 62: 32–36, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schelonka RL, Katz B, Waites KB, Benjamin DK., Jr Critical appraisal of the role of Ureaplasma in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia with metaanalytic techniques. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24: 1033–1039, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schelonka RL, Waites KB. Ureaplasma infection and neonatal lung disease. Semin Perinatol 31: 2–9, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu T, Kida Y, Kuwano K. Ureaplasma parvum lipoproteins, including MB antigen, activate NF-κB through TLR1, TLR2 and TLR6. Microbiology 154: 1318–1325, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soraisham AS, Singhal N, McMillan DD, Sauve RS, Lee SK. A multicenter study on the clinical outcome of chorioamnionitis in preterm infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200: 372e371–e376, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a continuing story. Semin Fetal Neonat Med 11: 354–362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speer CP. Pulmonary inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol 26, Suppl 1: S57–S62; discussion S63–S64, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stenmark KR, Abman SH. Lung vascular development: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 623–661, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thebaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 978–985, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Marter LJ, Dammann O, Allred EN, Leviton A, Pagano M, Moore M, Martin C. Chorioamnionitis, mechanical ventilation, and postnatal sepsis as modulators of chronic lung disease in preterm infants. J Pediatr 140: 171–176, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viscardi RM, Hasday JD. Role of Ureaplasma species in neonatal chronic lung disease: epidemiologic and experimental evidence. Pediatr Res 65: 84R–90R, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viscardi RM, Muhumuza CK, Rodriguez A, Fairchild KD, Sun CC, Gross GW, Campbell AB, Wilson PD, Hester L, Hasday JD. Inflammatory markers in intrauterine and fetal blood and cerebrospinal fluid compartments are associated with adverse pulmonary and neurologic outcomes in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 55: 1009–1017, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waites KB, Schelonka RL, Xiao L, Grigsby PL, Novy MJ. Congenital and opportunistic infections: Ureaplasma species and Mycoplasma hominis. Semin Fetal Neonat Med 14: 190–199, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walsh WF, Butler J, Coalson J, Hensley D, Cassell GH, deLemos RA. A primate model of Ureaplasma urealyticum infection in the premature infant with hyaline membrane disease. Clin Infect Dis 17, Suppl 1: S158–S162, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watterberg K, Demers L, Scott S, Murphy S. Chorioamnionitis and early lung inflammation in infants in whom bronchopulmonary dysplasia develops. Pediatrics 97: 210–215, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willet KE, Jobe AH, Ikegami M, Brennan S, Newnham J, Sly PD. Antenatal endotoxin and glucocorticoid effects on lung morphometry in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res 48: 782–788, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Witt A, Berger A, Gruber CJ, Petricevic L, Apfalter P, Worda C, Husslein P. Increased intrauterine frequency of Ureaplasma urealyticum in women with preterm labor and preterm premature rupture of the membranes and subsequent cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193: 1663–1669, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoder BA, Coalson JJ, Winter VT, Siler-Khodr T, Duffy LB, Cassell GH. Effects of antenatal colonization with ureaplasma urealyticum on pulmonary disease in the immature baboon. Pediatr Res 54: 797–807, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]