Abstract

Fetal exposure to inflammatory mediators is associated with a greater risk of brain injury and may cause endothelial dysfunction; however, nearly all the evidence is derived from gram-negative bacteria. Intrapleural injections of OK-432, a killed Su-strain of Streptococcus pyogenes, has been used to treat fetal chylothorax. In this study, we evaluated the neural and cardiovascular effects of OK-432 in preterm fetal sheep (104 ± 1 days, term 147 days). OK-432 (0.1 mg, n = 6) or saline vehicle (n = 7) was infused in the fetal pleura, and fetuses were monitored for 7 days. Blood samples were taken routinely for plasma nitrite measurement. Fetal brains were taken for histological assessment at the end of the experiment. Between 3 and 7 h postinjection, OK-432 administration was associated with transient suppression of fetal body and breathing movements and electtroencephalogram activity (P < 0.05), increased carotid and femoral vascular resistance (P < 0.05), but no change in blood pressure. Brain activity and behavior then returned to normal except in one fetus that developed seizures. OK-432 fetuses showed progressive, sustained vasodilatation (P < 0.05), with lower blood pressure after 4 days (P < 0.05), but normal heart rate. There were no changes in plasma nitrite levels. Histological studies showed bilateral infarction in the dorsal limb of the hippocampus of the fetus that developed seizures, but no injury in other fetuses. We conclude that a single low-dose injection of OK-432 can be associated with risk of focal cerebral injury in the preterm fetus and chronic central and peripheral vasodilatation that does not appear to be mediated by nitric oxide.

Keywords: prenatal infection, endothelial dysfunction, seizures

extensive clinical and experimental data strongly suggest that exposure of the preterm fetus to infection and inflammatory processes can trigger or exacerbate the development of neural injury (34). The mechanisms by which infection or inflammation may cause perinatal brain injury remain unclear but as with the adult are likely to be multifactorial, mediated through cytokine induction and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular impairment (34). Nearly all of this information is based on exposure to gram-negative bacteria and components such as Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS), with surprisingly limited information on the effects of gram-positive bacterial agents, despite their prevalence during pregnancy (30). Given that gram-positive bacteria induce toxicity through different pathways than gram-negative bacteria (32) and show marked differential stimulation of cytokine release (47), it is likely that their impact on the fetus is also different.

In adults, much of the acute morbidity associated with significant exposure to infection or inflammatory mediators is related to endothelial dysfunction, with altered release and sensitivity to vasodilators and vasoconstrictors, which in turn leads to hemodynamic instability and organ compromise (46). In the fetus, LPS has been associated with rather variable hemodynamic effects, likely reflecting differences in dose and timing of exposure between studies. Some studies observed no change in blood pressure or blood flow in fetal sheep (13–15), whereas others observed acute falls in blood pressure (5, 12, 20, 39), or a transient fall, followed by increased arterial blood pressure by 48–72 h recovery (20). Typically, early hypotension has been associated with cerebral vasodilatation that maintained perfusion and oxygen delivery (17, 39). In contrast, a recent study in the late-gestation sheep fetus found acute transient cerebral vasoconstriction after injection of LPS, followed by vasodilatation up to 24 h after three repeated injections (17). Vasodilatation was associated with evidence of transiently increased nitric oxide (NO) production (17) similarly to endotoxic shock in adults (48). However, the effects of gram-positive agents on fetal cardiovascular function have not been evaluated.

Gram-positive products have been used clinically. Fetal chylothorax and hydrothorax are relatively rare conditions that are associated with a high mortality and morbidity, primarily because of pulmonary hypoplasia (33). Recently, a sclerosant agent derived from killed low-virulence Su-strain, type 3 group A Streptoccocus pyogenes, OK-432 (Picibanil), which is used to reduce pleural effusion in adult patients with lung cancer, has been proposed as a promising treatment for fetuses with persistent pleural effusions in the early second trimester to alleviate hydrops fetalis and lung hypoplasia (9, 36).

We have recently established a relevant model of intrapleural injection of OK-432 in preterm fetal sheep and reported that a low clinical dose is associated with transient suppression of brain activity and fetal breathing and body movements, but no effect on fetal blood pressure in the first 12 h after OK-432 administration (11). However, the long-term impact on the brain and cardiovascular function is unknown. In the present study in the same cohort of animals (11), we evaluated the effect of intrapleural OK-432 on fetal brain activity, behavior, cardiovascular function, and plasma nitrite changes, as an index of NO activity (6, 10), for 7 days after exposure. At the conclusion of the experiment, fetal brains were taken for histopathology. The preterm fetal sheep at 0.7 gestation is neurologically comparable to the human brain at 28–32 wk of gestation (35), before the onset of cortical myelination (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of The University of Auckland, New Zealand. Thirteen time-mated singleton Romney-Suffolk cross sheep were operated on between 97 and 99 days gestation (term = 147 days). Food, but not water, was withdrawn 18 h before surgery. Ewes were given 5 ml of Streptocin [procaine penicillin (250,000 IU/ml)] and dihydrostreptomycin (250 mg/ml; Stockguard Labs, Hamilton, New Zealand) intramuscularly for prophylaxis 30 min before the start of surgery. Anesthesia was induced by intravenous injection of Alfaxan [Alphaxalone (3 mg/kg); Jurox, Rutherford, NSW, Australia], and general anesthesia was maintained using 2–3% isofluorane in O2. Ewes were not ventilated; the depth of anesthesia, maternal heart rate, and respiration were monitored by trained anesthetic staff. The ewes were given an intravenous infusion of isotonic saline at an infusion rate of ∼250 ml/h to maintain maternal fluid balance.

All surgical procedures were performed using sterile techniques as previously described (4, 11). Briefly, catheters were placed in the left femoral artery and vein for measurement of arterial and venous blood pressures, the right brachial artery for preductal blood sampling, the trachea for measurement of fetal breathing movements (FBMs), and the amniotic sac to permit correction for maternal movement by subtraction of amniotic fluid pressure from blood and tracheal pressures. A 3S ultrasound blood flow probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) was placed around the left carotid artery to measure carotid artery blood flow (CaBF) as an index of cerebral blood flow (4). A 2R probe was placed around the right femoral artery to measure femoral blood flow (FBF) as a representative peripheral resistance bed.

Electrocardiogram electrodes (Cooner Wire, Chatsworth, CA) were sewn across the fetal chest to record fetal heart rate (FHR). For the measurement of electrocorticogram (ECoG) activity, two pairs of electrodes were placed on the dura over the parasagittal parietal cortex (5 and 10 mm anterior to bregma and 5 mm lateral) and secured with cyanoacrylate glue (Selleys, Auckland, NZ). Two reference electrodes were sutured to the skin over the occiput. Electrodes were sewn in the muscle for the recording of nuchal electromyographic (EMG) activity (an index of body movements).

A saline-filled catheter made from silicone tubing (2.16 mm OD and 1.02 mm ID, Degania Silicone Tubing; Bamford, Lower Hutt, NZ) was placed in the right pleural space through a small incision in the seventh intercostal space, 1.5 cm lateral to the sternum. The pleura were sighted, and the catheter was inserted to a depth of 4 cm and then secured to muscle and skin (11).

The uterus was then closed, and antibiotics [80 mg gentamicin (Pharmacia and Upjohn, Rydalmere, New South Wales, Australia)] were administered in the amniotic sac. The maternal laparotomy skin incision was infiltrated with a local analgesic, 10 ml 0.5% bupivacaine plus epinephrine (AstraZeneca, Auckland, New Zealand). All fetal catheters and leads were exteriorized through the maternal flank. The maternal long saphenous vein was catheterized to provide access for postoperative maternal care and euthanasia.

Postoperatively, sheep were housed together in separate metabolic cages with access to water and food ad libitum. They were kept in a temperature-controlled room (16 ± 1°C, humidity 50 ± 10%), in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Antibiotics were administered daily intravenously to the ewe [600 mg benzylpencillin sodium (Novartis, Auckland, New Zealand) and 80 mg gentamicin (Pharmacia and Upjohn)]. Fetal vascular catheters were maintained patent by continuous infusion of heparinized saline (20 U/ml at 0.15 ml/h), and the maternal catheter was maintained by daily flushing.

Experimental Recordings

All physiological measurements were recorded continuously, and the data were stored to disk by custom software for off-line analysis (Labview for Windows, National Instruments, Austin, TX). The analog ECoG signal was processed with a first-order high-pass filter at 1.6 Hz and a sixth-order Butterworth low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 50 Hz. The total ECoG intensity was calculated on the intensity (power) spectrum between 1 and 20 Hz. For clarity of data display, the ECoG power was log transformed [ECoG amplitude (dB), 20 × log (power)]. The nuchal EMG signal was amplified (×4,000) and low-pass filtered, with the −3 dB point set to a cut-off frequency of 2 kHz. Signals were then band-pass filtered between 100 and 1 kHz and integrated using a time constant of 0.1 s.

Fetal pressures were measured continuously (Novatrans II pressure transducers, MX860, Carlsbad, CA). The signal from the pressure transducer was amplified ×500, and low-pass filtered, with the −3 dB point set to a cut-off frequency of 20 Hz. Carotid and femoral artery vascular resistance (CaVR and FVR, respectively) was calculated using the formula mean arterial pressure (MAP) − mean venous pressure/blood flow (mmHg·ml−1·min−1).

Experimental Design

Experiments were conducted 4–5 days after surgery at 104 ± 1 days gestation. Physiological data recordings were started 12 h before infusion and continued for 7 days after treatment to allow for the potential development of pleural adhesions and neuronal and glial injury and to evaluate the chronic vascular effects of exposure to OK-432. On the day of the experiment, arterial blood samples (0.3 ml) were taken from the brachial cannula for the measurement of pH, blood gases (Ciba-Corning Diagnostics 845 Blood Gas Analyzer/Co-oximeter, East Walpole, MA), and glucose/lactate (YSI 2300, Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH) at 1 h before infusion (baseline sample), 2 and 6 h after infusion, and daily thereafter. At the same time points, 2 ml of blood were taken on ice and immediately centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 rpm at 4°C, and the plasma was frozen at −80°C for the measurement of nitrite. Although nitrite is metabolized by hemoglobin, with a half-life of ∼8.5 min at body temperature (6), it is stable at 4°C and in plasma.

OK-432 (Picibanil; a gift from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) is derived from a low-virulence Su-strain of type 3 group A S. pyogenes. It was administered as a single dose of 1KE OK-432 (n = 6; 1KE is the equivalent of 0.1 mg dried streptococci) dissolved in 10 ml of sterile isotonic saline (11). This dose was based on the low range of clinically administered OK-432 (36) and was given as a slow push over 20 min in the pleural cavity through the pleural catheter. The same volume of normal saline was given to the control animals (n = 7). On completion of the experimental protocol, ewes and fetuses were killed by an intravenous overdose of pentobarbitone sodium (30 ml of 300 mg/ml) administered intravenously to the ewe. The fetus was removed, body and organs were weighed, and the position of the pleural catheter was checked.

Histological Procedures

For assessment of neural injury, fetal brains were perfusion fixed in situ via the carotid arteries with 250 ml of 0.9% saline solution followed by 500 ml of 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. Following removal from the skull, brain tissue was fixed in formalin for a further 3 days, before processing and embedding using a standard paraffin tissue preparation (23). Serial 6-μm coronal brain sections taken from 14, 19, and 27 mm anterior to stereotaxic zero were assessed for cell loss, activated microglial cells, or astrocytosis using light microscopy (Nikon E800, Tokyo, Japan) (22). The slides were coded for analysis by an independent member of the group to mask the slide identity for analysis. Illustrative photomicrographs were taken from the dorsal limb of the hippocampus and periventricular white matter.

For assessment of neuronal loss, brain sections were stained with thionin and acid fuchsin. Before being stained, slides were deparaffinized in xylene (2 × 15 min), hydrated in a series of ethanol (100, 95, and 70% for 2 min each), and then washed in distilled water for 1 × 5 min and 0.1 mol/l PBS for 2 × 5 min. Sections were then stained with thionin acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, Perth, WA, Australia) for 1 × 4 min and acid fuchsin for 1 × 30 s, followed by a quick wash in distilled water. The sections were then dehydrated and mounted.

Activated microglia were labeled using Bandeiraea simplicifolia isolectin-B4 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (42). Astrocytes were labeled with rabbit anti-bovine glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA; 1:2,000). Before specific staining, slides were deparaffinized in xylene (2 × 15 min), hydrated in a series of ethanol (100, 95, and 70% for 2 min each), and then washed in distilled water for 1 × 5 min and PBS for 2 × 5 min. Sections were then pretreated with 1% H2O2 in 100% methanol and then washed in distilled water for 5 min and PBS plus 1% Triton X-100 (PBS-T) for 2 × 5 min. Sections were then boiled in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer for 1 min for antigen retrieval and subsequently left to cool for 20 min at room temperature. Sections were then blocked in PBS + 2% normal goat serum + 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. The primary labels were then incubated overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were washed off with PBS (3 × 5 min) and then for GFAP incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG made in goat (VectaStain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA; 1:200); it was incubated for 4 h at room temperature.

Sections were then washed for 3 × 5 min in PBS-T, incubated in avidin-biotin complex (VectorStain Elite ABC Kit) in the ratio of 1:50 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature, washed in PBS (3 × 5 min), and then reacted in diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich). The reaction was stopped by washing in distilled water, and the sections were dehydrated and mounted.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase-Mediated dUTP-Biotin Nick-End Labeling

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP-biotin nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed on parallel sections to further validate the extent of cell death. Sections were pretreated for 30 min with proteinase K (40 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical), washed 3 × 5 min in PBS, and then kept for 30 min with methanol containing 1% H2O2 to block nonspecific peroxidase activity. Sections were then washed again for 3 × 5 min in PBS and incubated for 5 min with TdT buffer (GIBCO-BRL, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). DNA fragments were labeled with TdT and biotin-14-dATP (GIBCO-BRL) for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, sections were washed for 2 × 15 min in SSC buffer and incubated for 2 h with ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories). After being washed for 2 × 5 min in PBS, the sections were developed with DAB. Sections were dehydrated and mounted. A section that was pretreated with DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) to nick all DNA served as a positive control. A negative control slide was obtained with the omission of TdT from the incubation solution.

Plasma Nitrite Measurements

Plasma (300 μl) was deproteinized by addition of an equal volume of methanol followed by vortexing and centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 relative centrifugal force. The supernatant was then injected in a purge vessel containing acidified triiodide solution to reduce nitrite to NO as previously described (6, 40). The triiodide was sparged with a stream of argon gas that carried the resulting NO gas into a chemiluminescence analyzer (Sievers 280i NO Analyzer; GE Analytical Instruments, Boulder, CO). Nitrite concentrations were quantified by comparison with injections of known nitrite standards. The assay enables quantification of nitrite concentrations >10 nM with a precision of ±5 nM and does not detect nitrate at concentrations <1 mM.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Off-line analysis of the physiological data was performed using custom analysis programs (Labview for Windows). One-hour average data were calculated, and the baseline period was taken as the mean of the 12 h before infusion. The raw ECoG record was assessed for epileptiform transient activity (ECoG transients), specifically the presence of spikes and sharp waves that were defined as having a duration between 70 and 250 ms and an amplitude >10 μV (3). Overt electrographic seizures were identified visually and defined as the concurrent appearance of sudden, repetitive, evolving stereotyped waveforms in the ECoG lasting >10 s and having an amplitude >20 μV (45). Vascular resistance was calculated off-line as mean arterial blood pressure minus mean venous blood pressure (perfusion pressure) divided by blood flow (mmHg·ml−1·min−1).

The effect of treatment on fetal physiological parameters and blood composition data was evaluated by ANOVA, using time as a repeated measure and using baseline values as a covariate (ANOVA, SPSS version 15; SPSS, Chicago, IL) followed by Fisher's protected least-significant difference post hoc test when a significant overall effect of group or an interaction between group and time was found. Statistical significance was accepted when P < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SE, except where data are reported for one animal (means ± SD).

RESULTS

Fetal postmortem observations.

One fetus died 6 days after receiving OK-432; the remaining fetuses completed the 7-day protocol. Evaluation of the thoracic cavity showed that the pleural catheters were in place in all fetuses. Focal pleural adhesions around the tip of the infusion catheter were seen in the all OK-432 fetuses and no controls (11). There was no difference in fetal weight after OK-432 compared with control (2,078 ± 91 vs. 1,955 ± 86 g) or in brain weight (31.9 ± 1.1 vs. 31.4 ± 2.7 g) or numbers of males vs. females (2/4 vs. 2/5).

Blood composition.

There were no significant differences between groups before or after infusion for any parameter; in particular, there was no significant difference in fetal PaO2 values after OK-432 infusion (Table 1). There were also no changes in fetal hemoglobin, hematocrit, and arterial oxygen saturation (data not shown).

Table 1.

Blood composition data from the OK-432 and control groups, before (baseline) and after (2 and 6 h or 1, 3, and 7 days) OK-432 or vehicle (control) injection

| Group | Baseline | 2 Hours | 6 Hours | 1 Day | 3 Days | 5 Days | 7 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | |||||||

| OK-432 | 7.36 ± 0.0 | 7.38 ± 0.0 | 7.38 ± 0.0 | 7.39 ± 0.0 | 7.35 ± 0.0 | 7.34 ± 0.0 | 7.35 ± 0.0 |

| Control | 7.36 ± 0.0 | 7.37 ± 0.0 | 7.39 ± 0.0 | 7.36 ± 0.0 | 7.37 ± 0.0 | 7.36 ± 0.0 | 7.36 ± 0.1 |

| PaO2, mmHg | |||||||

| OK-432 | 24.4 ± 1.7 | 25.1 ± 1.2 | 24.1 ± 1.0 | 21.8 ± 0.6 | 24.6 ± 1.6 | 24.9 ± 2.0 | 23.6 ± 1.0 |

| Control | 26.1 ± 1.2 | 24.6 ± 1.8 | 24.5 ± 1.3 | 24.8 ± 1.3 | 25.7 ± 2.4 | 24.8 ± 1.3 | 26.5 ± 1.9 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | |||||||

| OK-432 | 49.1 ± 1.6 | 46.4 ± 1.3 | 47.8 ± 1.4 | 47.1 ± 1.5 | 46.4 ± 2.8 | 48.3 ± 1.2 | 50.0 ± 1.5 |

| Control | 46.3 ± 1.0 | 48.3 ± 1.0 | 46.3 ± 2.0 | 48.3 ± 12 | 49.5 ± 1.4 | 45.3 ± 1.2 | 51.0 ± 2.8 |

| Glucose, mM | |||||||

| OK-432 | 1.03 ± 0.1 | 1.07 ± 0.1 | 1.03 ± 0.1 | 0.94 ± 0.1 | 1.05 ± 0.1 | 1.01 ± 0.1 | 1.04 ± 0.1 |

| Control | 1.10 ± 0.2 | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 1.03 ± 0.0 | 1.03 ± 0.2 | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 1.01 ± 0.1 |

| Lactate, mM | |||||||

| OK-432 | 0.71 ± 0.1 | 0.78 ± 0.1 | 0.97 ± 0.1 | 0.72 ± 0.1 | 0.73 ± 0.1 | 0.82 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Control | 0.85 ± 0.1 | 0.89 ± 0.1 | 0.93 ± 0.1 | 0.81 ± 0.0 | 0.81 ± 0.1 | 0.87 ± 0.1 | 0.83 ± 0.1 |

PaO2, Partial pressure of oxygen; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide. Given that there were no significant differences in any of the daily time points, for clarity, selected days (1, 3, 5, and 7) only are shown.

Fetal Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

Blood pressure.

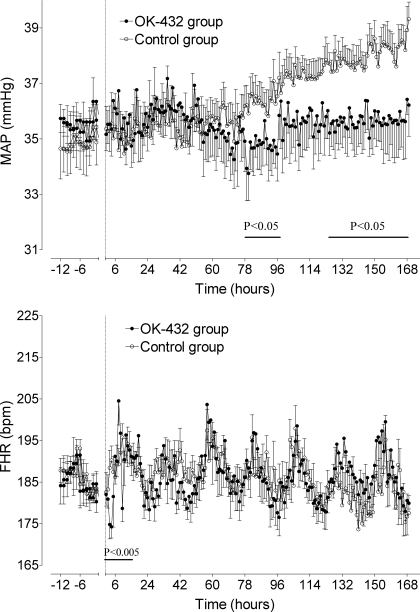

There were no significant differences in MAP between groups in the baseline period (Fig. 1, top). After OK-432 and vehicle injections, there were significant differences between groups between 78 and 96 h (P < 0.05) and again between 125 h and the end of the experiment (P < 0.05). From days 5 to 7, MAP was 38.2 ± 0.8 mmHg in the control group compared with 35 ± 0.7 mmHg in the OK-432 group (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Time sequence changes in mean arterial blood pressure (MAP, top) and fetal heart rate (FHR, bottom) in the control group (○) and OK-432 group (●). Data are 1-h averages (means ± SE) from 12 h before injection (dotted line) until 168 h (7 days) after injection.

Fetal heart rate.

There were no significant differences in FHR between groups in the baseline period (Fig. 1, bottom). There was a significant interaction between group and time during the first 12 h in the OK-432 group (P < 0.005). Post hoc analysis showed that FHR was significantly lower in the OK-432 group compared with the control group with the fall in FHR maximal at 4 h (174 ± 2.7 vs. 196 ± 3.4 beats/min, P < 0.005). FHR returned to control group values by 5 h, and this was followed by a transient period of tachycardia at 8 h (204 ± 5.8 vs. 189 ± 3.7 beats/min, P < 0.05) and a brief period of bradycardia at 10 h (P < 0.005). Thereafter, there were no significant differences between groups in basal heart rate or in the diurnal pattern of heart rate.

Fetal Carotid and FBFs and Vascular Resistance

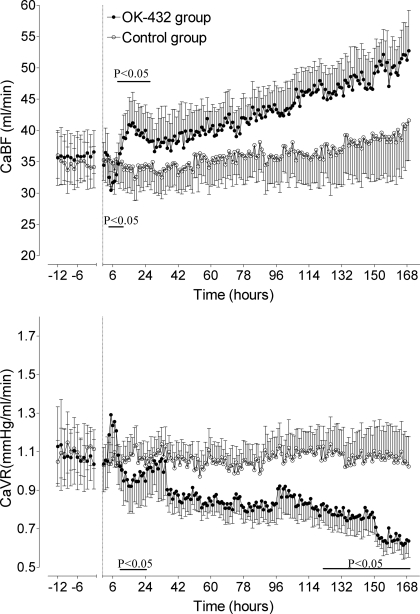

Carotid blood flow.

There were no significant differences in CaBF (Fig. 2, top) or CaVR (Fig. 2, bottom) between groups in the baseline period. In the OK-432 group, there was a significant difference in CaBF between groups over the first 24 h (P < 0.05). Post hoc analysis showed that CaBF significantly fell in the OK-432 group between 4 and 8 h, with the fall maximal at 5 h (29.7 ± 3.6 vs. 35.1 ± 4.1 ml/min, P < 0.05). CaBF was then significantly transiently elevated from 11 to 12 h, with CaBF peaking at 17 h (41.2 ± 5.0 vs. 34.2 ± 3.8 ml/min, P < 0.05) before returning to control group values. Both groups significantly increased over time (P < 0.01), but, although there was a trend for CaBF to be greater in the OK-432 group, this was not significantly different.

Fig. 2.

Time sequence changes in carotid blood flow (CaBF, top) and carotid vascular resistance (CaVR, bottom) in the control group (○) and OK-432 group (●). Data are means ± SE from 12 h before injection (dotted line) until 168 h (7 days) after injection. Bar denotes significance, P < 0.05 control vs. OK-432.

Carotid vascular resistance.

In the OK-432 group, CaVR transiently increased between 4 and 8 h, peaking at 5 h, but this was not significantly different between groups. CaVR fell in both groups over time (P < 0.005, Fig. 2, bottom) and was significantly lower in the OK-432 group between 10 and 20 h (P < 0.05), with the nadir occurring at 16 h (0.91 ± 0.1 vs. 1.08 ± 0.1 mmHg·ml−1·min−1, P < 0.005). There was a significant change in CaVR over time in both groups, with CaVR falling. CaVR was significantly lower in the OK-432 group from 130 h until the end of experiment (P < 0.05).

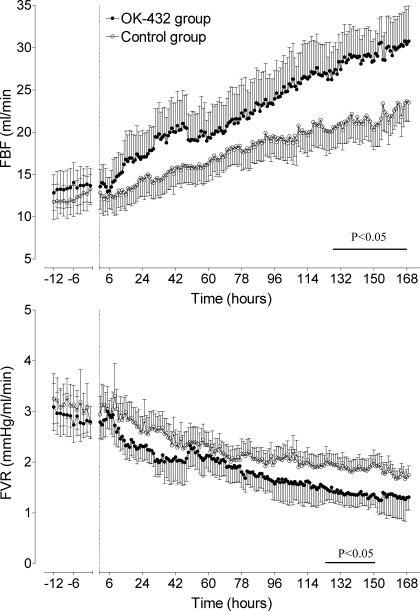

FBF and vascular resistance.

There were no significant differences in FBF (Fig. 3, top) or FVR (Fig. 3, bottom) between groups in the baseline period. Both groups significantly increased over time (P < 0.05), and FBF was higher in the OK-432 group from 130 h until the end of experiment (the average for this period in the OK-432 group was 29.2 ± 3.3 vs. 22.0 ± 4.2 ml/min in the control group, P < 0.05). There was a significant reduction in FVR in both groups over time (P < 0.01), and FVR was lower in the OK-432 group between 135 and 150 h (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Time sequence changes in femoral blood flow (FBF, top) and femoral artery vascular resistance (FVR, bottom) in the control group (○) and OK-432 group (●). Data are means ± SE from 12 h before injection (dotted line) until 168 h (7 days) after injection. Bar denotes significance, P < 0.05 control vs. OK-432.

Plasma Nitrite Measurements

There were no significant differences in plasma nitrite measurements between groups before or after administration of OK-432, and no changes over time. The mean nitrite levels in the last 48 h were 0.16 ± 0.02 vs. 0.15 ± 0.03 μmol/l (not significant).

Fetal Behavior

Fetal body movements.

There were no differences in nuchal EMG activity or FBMs between groups during the baseline period. OK-432 infusion was associated with suppression of EMG activity between 3 and 6 h after injection (P = 0.007) (11), thereafter returning to control group values for the remainder of the experiment.

Fetal breathing movements.

In the OK-432 group, apnea was observed starting around 2 h (117 ± 7.2 min, range 86–139 min) and lasting for around 2 h (116 ± 13.0 min, range 89–182 min) (11). This was followed by a further 2.5 h of reduced amplitude and frequency of FBMs; thereafter, FBMs returned to control group values.

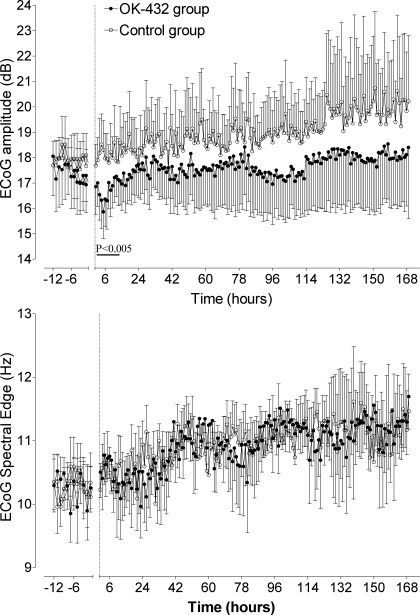

Fetal ECoG Activity

There was no significant difference in baseline ECoG amplitude (Fig. 4, top) or spectral edge (Fig. 4, bottom) between groups. After OK-432 injection, ECoG amplitude was significantly suppressed between 4 and 7 h (maximal suppression 15.4 ± 1.1 vs. 18.3 ± 1.1 dB, at 5 h, P < 0.005). Thereafter, there was a significant increase in both groups over time (P < 0.001), with no difference between groups. There was no significant difference in ECoG spectral edge at any time period between groups.

Fig. 4.

Time sequence changes in electrocorticogram (ECoG) amplitude (dB, top) and spectral edge (Hz, bottom) in the control group (○) and OK-432 group (●). Data are means ± SE from 12 h before injection (dotted line) until 168 h (7 days) after injection. Bar denotes significance, P < 0.005 control vs. OK-432.

Seizures

One fetus developed electrographic seizures. Repetitive, evolving stereotyped waveforms lasting >10 s and with amplitude >20 μV were observed, starting 18 h after the end of OK-432 administration. These seizures were infrequent (∼2/h at the peak of the events) and lasted an average of 76 ± 21 s (mean ± SD). The mean peak amplitude was 165 ± 43.6 μV, ranging up to 580 μV. The amplitude of seizures decreased over time, and no further seizures were observed from 55 h after the end of injection. In addition to overt seizures, epileptiform transients also developed. High-amplitude sharp and slow waves were present from 1 h before the occurrence of the first large seizure and lasted until 4 days after injection. In this fetus, they occurred at a rate of 600 ± 125/h, mean amplitude 102 ± 76 μV, were most frequent on days 2–4, and were no longer seen after 5 days. In addition, lower-amplitude events were observed (peak amplitude 55 ± 11.2 μV), characterized by a uniform sinusoidal waveform, with a frequency of two to three events every 30 min, lasting 86 ± 32 s. These events were seen from 2 to 6 days after injection.

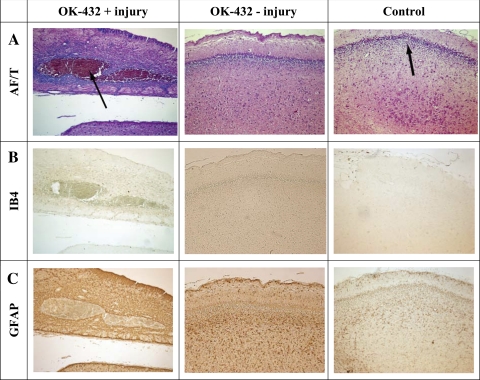

Histology

There were no histological differences between groups except in the one OK-432 fetus that developed seizures, as described above. In this fetus, a large infarct was observed on both sides of the hippocampus, encompassing CA1 through CA4 (Fig. 5), with marked local induction of microglia but no apparent increase in astrocytes. Injury as shown by tissue damage, TUNEL staining, and induction of microglia or astrocytosis was not observed in any other white or gray matter area (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Photomicrographs of the hippocampal region from the OK-432 treatment fetus with injury, an OK-432 treatment fetus without injury, and a control fetus. A: acid fuchsin/thionin (AF/T); note a large area of infarction indicated by an arrow. There is no injury in the other two groups. The arrow in the control fetus of A indicates the CA1 region. Isolectin B4 staining (IB4, B) indicates activated microglia in the area of the infarct, but no activated microglia in the other groups. Glial fibrillary acidic protein staining (GFAP, C) indicated that there was no increase in activated astrocytes 7 days after OK-432 infusion. Taken at ×10 magnification.

DISCUSSION

OK-432 is derived from a low-virulence Su-strain of type 3 group A S. pyogenes (a gram-positive bacteria) killed with benzylpencillin and heat to eliminate its toxin-producing capacity and ability to proliferate (37, 44). We demonstrate that OK-432 exposure was associated with acute, transient vasoconstriction followed by slowly evolving but persistent vasodilatation and increased central and peripheral blood flow, up to at least 1 wk after exposure. Although overt hypotension did not occur, there was a striking loss of the normal maturational increase in fetal arterial blood pressure. There were no changes in circulating concentrations of nitrite, suggesting that the cardiovascular changes were not related to altered NO production.

There is now compelling evidence that exposure of the fetus to bacterial products such as gram-negative endotoxin (LPS) can trigger neural injury in the developing brain (49), albeit the severity can be highly variable. In the present study, with an intact gram-positive agent, we observed one case of severe bilateral hippocampal infarction, with local hemorrhage and microglial induction, out of five surviving fetuses exposed to OK-432 after 7 days recovery, but no control fetuses. No other histological damage was observed in the other OK-432 fetuses, and in particular there was no evidence of white matter injury. Although damage was highly localized in a single fetus, this occurred after a single, low-clinical dose of OK-432 (36). It is unknown whether the risk would be higher with higher doses or repeated treatment. Although there was one experimental death in the OK-432 group, this occurred 6 days after exposure to the agent, the fetus did not exhibit epileptiform activity and had an identical trajectory of cardiovascular changes to the rest of the group until shortly before death, and so appeared unrelated to exposure to OK-432, but this cannot be ruled out.

The single case of neural injury occurred despite normal blood gases and stable mean arterial blood pressure. Although inflammation may alter the threshold for seizures (29), and can exacerbate seizure-induced neuronal damage in the hippocampus (1), given that the events started around 18 h after injection in this fetus, it is probable that in the present study seizures reflected evolving injury. Furthermore, they occurred well before the period of relative hypoperfusion discussed below, and so it is improbable that injury was secondary to perfusion changes. Neural damage associated with infection appears to be primarily due to neurotoxicity, probably mediated through the cytokine/microglial response (49).

OK-432 was associated with transient suppression of ECoG activity and body and breathing movements, as previously reported (11). The suppression of brain and body activity was associated with a transient fall in central and peripheral blood flows, consistent with reports in pre- and postnatal animals (16, 17, 26, 38). This vasoconstriction was not associated with any change in plasma nitrite, a product of oxidation of NO that provides a sensitive in vivo index of NO synthase (NOS) activity (6, 28). Potentially, there could have been dysregulation of the release of, or sensitivity to, vasoconstrictors (19, 25). Alternatively, the close correlation in time between carotid vasoconstriction and suppression of the electroencephalogram in the present study supports the hypothesis that there was an appropriate reduction of blood flow in response to reduced brain metabolism.

Normal fetal growth is associated with a progressive rise in MAP of ∼0.46 mmHg/day in the fetal sheep (7, 27), consistent with the changes in the control group in the present study. This is in part associated with changes in total combined ventricular output and sympathetic and vasopressinergic tone (21). In contrast, OK-432 exposure was associated with long-lasting central and peripheral vasodilatation with increased blood flows and loss of the normal maturational increase in arterial blood pressure. Thus, although hypotension did not develop after OK-432, arterial blood pressure was modestly but consistently lower than in the control group by the end of the study. FBF rose progressively, whereas there was a more rapid relative increase in CaBF that peaked around 12 h similar to the increase seen after endotoxin exposure both pre- and postnatally (8, 17, 39, 43). Despite the progressive vasodilatation, there were no apparent compensatory changes in combined ventricular output since FHR returned to normal values, with normal diurnal rhythm, denoting a primary change in vascular tone or endothelial function. Furthermore, in all but the injured fetus, ECoG and behavior returned to normal within 12 h, and there was no difference in body weight between groups at the end of the experiment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in the fetus of a persistent change in vascular tone after exposure to LPS or other infectious agents.

Impaired contractility of the vascular smooth muscle after gram-negative endotoxin or bacterial exposure is typically reported to be mediated by greater activity of inducible NOS (iNOS) (48). Similarly, a rise in combined nitrite/nitrate concentrations has been observed after LPS infusion in late-gestation fetal sheep (17). In contrast, we found no change in nitrite levels in the present study after exposure to killed gram-positive bacteria. Gram-positive bacteria can also acutely induce NO production via lipoteichoic acid (24), but the long-term effects are unclear. It is important to note that, in term fetal sheep, LPS injection was associated with a transient increase in total nitrite/nitrate only after the first bolus of LPS, with no change after subsequent boluses even though transient vasodilation still occurred (17). These data suggest a relatively limited role for NO in mediating subacute infection-related vasodilatation in the fetus.

Other possible mediators of altered vascular tone include altered responsiveness of the vasculature to vasodilator stimuli, induction of other vasodilators, such as the contact (kallikrein/kinin) system (18), or altered release of, or sensitivity to, vasoconstrictors (31, 48). However, in humans, vascular hyporeactivity to adrenergic stimulation after exposure to endotoxemia can occur in the absence of increased NO activity or iNOS expression (41). These data are consistent with the present study and argue against a major contribution of vascular iNOS activity to the systemic vasodilation to infection.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the early transient neural suppression associated with intrapleural infusion of the sclerosant agent OK-432 in preterm fetal sheep rapidly resolves and, in most fetuses, had no medium-term effect on brain activity or behavior. However, this study indicates that there is a risk of seizures and severe neural injury in some fetuses even after low-dose therapy. Because chylothorax has a very high mortality, and survivors are exposed to serious neonatal complications, including the increased risk of brain injury after preterm birth (34, 49), occasional risks from therapy may be acceptable if this therapy is the most effective at reducing pleural effusions. Pragmatically, these data suggest that it would be prudent to evaluate OK-432 more thoroughly in a range of experimental animal models before promoting its use in the human fetus.

Perspectives and Significance

This study has demonstrated the potential for a single low-dose exposure of OK-432 to induce a persistent chronic central and peripheral vasodilatation. Changes in vascular resistance are, of course, not necessarily harmful in themselves, and the vascular changes we observed were relatively modest, albeit persistent. We do not know if this vasodilatation would resolve or whether it permanently altered the trajectory of fetal blood pressure, which in turn may have implications for postnatal blood pressure development and control. Furthermore, altered endothelial function could potentially compromise the ability of the fetus to adapt to events such as hypoxia where peripheral vasoconstriction is necessary to support blood pressure.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from the Mercia Barnes Trust (New Zealand), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Auckland Medical Research Foundation and the Lottery Grants Board of New Zealand, and the National Institutes of Health (HL-09597 to A. B. Blood). OK-432 was a gift from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Shannon Bragg.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auvin S, Shin D, Mazarati A, Nakagawa J, Miyamoto J, Sankar R. Inflammation exacerbates seizure-induced injury in the immature brain. Epilepsia 48: 27–34, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow RM. The foetal sheep: morphogenesis of the nervous system and histochemical aspects of myelination. J Comp Neurol 135: 249–262, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennet L, Dean JM, Wassink G, Gunn AJ. Differential effects of hypothermia on early and late epileptiform events after severe hypoxia in preterm fetal sheep. J Neurophysiol 97: 572–578, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennet L, Roelfsema V, Dean J, Wassink G, Power GG, Jensen EC, Gunn AJ. Regulation of cytochrome oxidase redox state during umbilical cord occlusion in preterm fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1569–R1576, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blad S, Welin AK, Kjellmer I, Rosen KG, Mallard C. ECG and heart rate variability changes in preterm and near-term fetal lamb following LPS exposure. Reprod Sci 15: 572–583, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blood AB, Power GG. In vitro and in vivo kinetic handling of nitrite in blood: effects of varying hemoglobin oxygen saturation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1508–H1517, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boddy K, Dawes GS, Fisher R, Pinter S, Robinson JS. Foetal respiratory movements, electrocortical and cardiovascular responses to hypoxaemia and hypercapnia in sheep. J Physiol 243: 599–618, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brian JE, Jr, Heistad DD, Faraci FM. Mechanisms of endotoxin-induced dilatation of cerebral arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H783–H788, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen M, Shih JC, Wang BT, Chen CP, Yu CL. Fetal OK-432 pleurodesis: complete or incomplete? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 26: 791–793, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conahey GR, Power GG, Hopper AO, Terry MH, Kirby LS, Blood AB. Effect of inhaled nitric oxide on cerebrospinal fluid and blood nitrite concentrations in newborn lambs. Pediatr Res 64: 375–380, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowie RV, Stone PR, Parry E, Jensen EC, Gunn AJ, Bennet L. Acute behavioral effects of intrapleural OK-432 (Picibanil) administration in preterm fetal sheep. Fetal Diagn Ther 25: 304–313, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalitz P, Harding R, Rees SM, Cock ML. Prolonged reductions in placental blood flow and cerebral oxygen delivery in preterm fetal sheep exposed to endotoxin: possible factors in white matter injury after acute infection. J Soc Gynecol Investig 10: 283–290, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan JR, Cock ML, Scheerlinck JP, Westcott KT, McLean C, Harding R, Rees SM. White matter injury after repeated endotoxin exposure in the preterm ovine fetus. Pediatr Res 52: 941–949, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan JR, Cock ML, Suzuki K, Scheerlinck JP, Harding R, Rees SM. Chronic endotoxin exposure causes brain injury in the ovine fetus in the absence of hypoxemia. J Soc Gynecol Investig 13: 87–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eklind S, Mallard C, Leverin AL, Gilland E, Blomgren K, Mattsby-Baltzer I, Hagberg H. Bacterial endotoxin sensitizes the immature brain to hypoxic–ischaemic injury. Eur J Neurosci 13: 1101–1106, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekstrom-Jodal B, Elfverson J, Larsson LE. Early effects of E. coli endotoxin on superior sagittal sinus blood flow: an experimental study in dogs. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 26: 171–174, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng SY, Phillips DJ, Stockx EM, Yu VY, Walker AM. Endotoxin has acute and chronic effects on the cerebral circulation of fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R640–R650, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frick IM, Bjorck L, Herwald H. The dual role of the contact system in bacterial infectious disease. Thromb Haemost 98: 497–502, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardiner SM, Kemp PA, March JE, Bennett T. Temporal differences between the involvement of angiotensin II and endothelin in the cardiovascular responses to endotoxaemia in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol 119: 1619–1627, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garnier Y, Frigiola A, Li Volti G, Florio P, Frulio R, Berger R, Alm S, von Duering MU, Coumans AB, Reis FM, Petraglia F, Hasaart TH, Abella R, Mufeed H, Gazzolo D. Increased maternal/fetal blood S100B levels following systemic endotoxin administration and periventricular white matter injury in preterm fetal sheep. Reprod Sci 16: 758–766, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giussani DA, Forhead AJ, Fowden AL. Development of cardiovascular function in the horse fetus. J Physiol 565: 1019–1030, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gluckman PD, Parsons Y. Stereotaxic method and atlas for the ovine fetal forebrain. J Dev Physiol 5: 101–128, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunn AJ, Gunn TR, de Haan HH, Williams CE, Gluckman PD. Dramatic neuronal rescue with prolonged selective head cooling after ischemia in fetal lambs. J Clin Invest 99: 248–256, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han SH, Kim JH, Seo HS, Martin MH, Chung GH, Michalek SM, Nahm MH. Lipoteichoic acid-induced nitric oxide production depends on the activation of platelet-activating factor receptor and Jak2. J Immunol 176: 573–579, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernanz R, Briones AM, Alonso MJ, Vila E, Salaices M. Hypertension alters role of iNOS, COX-2, and oxidative stress in bradykinin relaxation impairment after LPS in rat cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H225–H234, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John E, Pais P, Furtado N, Chin A, Radhakrishnan J, Fornell L, Lumpaopong A, Beier UH. Early effects of lipopolysaccharide on cytokine release, hemodynamic and renal function in newborn piglets. Neonatology 93: 106–112, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitanaka T, Alonso JG, Gilbert RD, Siu BL, Clemons GK, Longo LD. Fetal responses to long-term hypoxemia in sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 256: R1348–R1354, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Lauer T, Rassaf T, Schindler A, Picker O, Scheeren T, Godecke A, Schrader J, Schulz R, Heusch G, Schaub GA, Bryan NS, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med 35: 790–796, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacs Z, Kekesi KA, Szilagyi N, Abraham I, Szekacs D, Kiraly N, Papp E, Csaszar I, Szego E, Barabas K, Peterfy H, Erdei A, Bartfai T, Juhasz G. Facilitation of spike-wave discharge activity by lipopolysaccharides in Wistar Albino Glaxo/Rijswijk rats. Neuroscience 140: 731–742, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer HM, Schutte JM, Zwart JJ, Schuitemaker NW, Steegers EA, van Roosmalen J. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity from sepsis in the Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 88: 647–653, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange M, Broking K, Hucklenbruch C, Ertmer C, Van Aken H, Lucke M, Bone HG, Westphal M. Hemodynamic effects of titrated norepinephrine in healthy versus endotoxemic sheep. J Endotoxin Res 13: 53–57, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehnardt S, Henneke P, Lien E, Kasper DL, Volpe JJ, Bechmann I, Nitsch R, Weber JR, Golenbock DT, Vartanian T. A mechanism for neurodegeneration induced by group B streptococci through activation of the TLR2/MyD88 pathway in microglia. J Immunol 177: 583–592, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longaker MT, Laberge JM, Dansereau J, Langer JC, Crombleholme TM, Callen PW, Golbus MS, Harrison MR. Primary fetal hydrothorax: natural history and management. J Pediatr Surg 24: 573–576, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malaeb S, Dammann O. Fetal inflammatory response and brain injury in the preterm newborn. J Child Neurol 24: 1119–1126, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McIntosh GH, Baghurst KI, Potter BJ, Hetzel BS. Foetal brain development in the sheep. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 5: 103–114, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nygaard U, Sundberg K, Nielsen HS, Hertel S, Jorgensen C. New treatment of early fetal chylothorax. Obstet Gynecol 109: 1088–1092, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okawa T, Takano Y, Fujimori K, Yanagida K, Sato A. A new fetal therapy for chylothorax: pleurodesis with OK-432. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 18: 376–377, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker JL, Emerson TE., Jr Cerebral hemodynamics, vascular reactivity, and metabolism during canine endotoxin shock. Circ Shock 4: 41–53, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peebles DM, Miller S, Newman JP, Scott R, Hanson MA. The effect of systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide on cerebral haemodynamics and oxygenation in the 0.65 gestation ovine fetus in utero. Br J Obstet Gynecol 110: 735–743, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelletier MM, Kleinbongard P, Ringwood L, Hito R, Hunter CJ, Schechter AN, Gladwin MT, Dejam A. The measurement of blood and plasma nitrite by chemiluminescence: pitfalls and solutions. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 541–548, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pleiner J, Heere-Ress E, Langenberger H, Sieder AE, Bayerle-Eder M, Mittermayer F, Fuchsjager-Mayrl G, Bohm J, Jansen B, Wolzt M. Adrenoceptor hyporeactivity is responsible for Escherichia coli endotoxin-induced acute vascular dysfunction in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 95–100, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roelfsema V, Bennet L, George S, Wu D, Guan J, Veerman M, Gunn AJ. The window of opportunity for cerebral hypothermia and white matter injury after cerebral ischemia in near-term fetal sheep. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 24: 877–886, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosengarten B, Hecht M, Auch D, Ghofrani HA, Schermuly RT, Grimminger F, Kaps M. Microcirculatory dysfunction in the brain precedes changes in evoked potentials in endotoxin-induced sepsis syndrome in rats. Cerebrovasc Dis 23: 140–147, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryoma Y, Moriya Y, Okamoto M, Kanaya I, Saito M, Sato M. Biological effect of OK-432 (picibanil) and possible application to dendritic cell therapy. Anticancer Res 24: 3295–3301, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scher M. Neonatal seizures: an expression of fetal or neonatal brain disorders. In: Fetal and Neonatal Brain Injury Mechanisms, Management and the Risks of Practice, edited by Stevenson DK, Benitz WE, Sunshine P. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press, 2003, p. 735–784 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sessler CN, Shepherd W. New concepts in sepsis. Curr Opin Crit Care 8: 465–472, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skovbjerg S, Martner A, Hynsjo L, Hessle C, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE, Tham W, Wold AE. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria induce different patterns of cytokine production in human mononuclear cells irrespective of taxonomic relatedness. J Interferon Cytokine Res 30: 23–32, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiemermann C. Nitric oxide and septic shock. Gen Pharmacol 29: 159–166, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X, Rousset CI, Hagberg H, Mallard C. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and perinatal brain injury. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 11: 343–353, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]