Abstract

The urethral rhabdosphincter and pelvic floor muscles are important in maintenance of urinary continence and in preventing descent of pelvic organs [i.e., pelvic organ prolapse (POP)]. Despite its clinical importance and complexity, a comprehensive review of neural control of the rhabdosphincter and pelvic floor muscles is lacking. The present review places historical and recent basic science findings on neural control into the context of functional anatomy of the pelvic muscles and their coordination with visceral function and correlates basic science findings with clinical findings when possible. This review briefly describes the striated muscles of the pelvis and then provides details on the peripheral innervation and, in particular, the contributions of the pudendal and levator ani nerves to the function of the various pelvic muscles. The locations and unique phenotypic characteristics of rhabdosphincter motor neurons located in Onuf's nucleus, and levator ani motor neurons located diffusely in the sacral ventral horn, are provided along with the locations and phenotypes of primary afferent neurons that convey sensory information from these muscles. Spinal and supraspinal pathways mediating excitatory and inhibitory inputs to the motor neurons are described; the relative contributions of the nerves to urethral function and their involvement in POP and incontinence are discussed. Finally, a detailed summary of the neurochemical anatomy of Onuf's nucleus and the pharmacological control of the rhabdosphincter are provided.

Keywords: urethra, incontinence, micturition, defecation, pelvic organ prolapse

the urethral rhabdosphincter and pelvic floor muscles are important in the maintenance of urinary continence and in preventing descent of pelvic organs [i.e., pelvic organ prolapse (POP)]. It is estimated that 11% of US women will undergo a surgical procedure for POP or urinary incontinence during their lifetimes (127). Despite the importance of understanding pelvic floor function, literature remains confusing in regard to both anatomy and innervation of pelvic floor muscles and the related urethral and anal rhabdosphincters. While an excellent review of functional anatomy of the pelvic floor has been published (3), reviews on innervation and neural control of pelvic floor muscles and the urethral and anal rhabdosphincter are rare.

Structural Elements of the Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor (3) in women is a bowl-shaped structure comprised of bone, muscle, and connective tissue. The rim of the bowl is formed by the bones of the pelvic girdle (sacrum, ilium, ischium, and pubis). The bottom of the bowl is lined with striated muscle: the iliococcygeus and pubococcygeus (which together comprise the levator ani muscle), coccygeus, and puborectalis muscles (Figs. 1 and 2). The muscles are attached to the bone and to each other with various connective tissue supports. These three components (bone, muscle, connective tissue) provide support of the pelvic viscera (i.e., rectum, vagina, bladder) and also allow for excretory and sexual function.

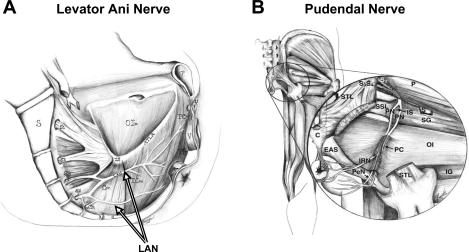

Fig. 1.

A: sagittal drawing of medial surface of a woman's pelvic floor showing the course of the levator ani nerve (LAN) from the sacral roots (S3–S5) across the internal surface of coccygeus (Cm), iliococcygeus (ICm), puborectalis (PRm), and pubococcygeus (PCm) muscles. S, sacrum; C, coccyx; IS, ischial spine; OIm, obturator internus muscle; ATLA, arcus tendineus levator ani; U, urethra; V, vagina; R, rectum. B: drawing of a posterior view of the hip muscles showing the course of the pudendal nerve (PN) from the S2-S4 roots across the lateral surface of the superior gemellus (SG) and OIm, through the pudendal canal (PC) and its branching into the inferior rectal nerve (IRN) and perineal nerve (PeN). P, periformis muscle; STL, sacroturberous ligament; SSL, sacrospinous ligament; S, sciatic nerve; EAS, external anal sphincter; IG, inferior gemellus muscle. [Adapted from Barber et al. (4).]

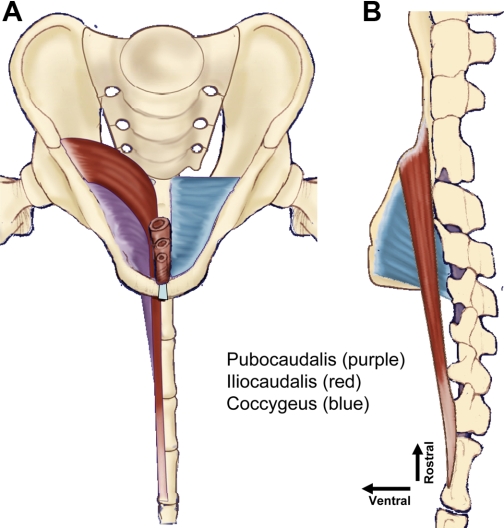

Fig. 2.

Drawing of origins and insertions of the primary pelvic floor muscles in the rat from the frontal (A) and right side sagital (B) views. In the frontal view (A), the iliocaudalis and the pubocaudalis muscles have been removed from the right side to allow visualization of the underlying coccygeus muscle. The iliocaudalis muscle [origin from the ilium, insertion on caudal vertebrae 5 and 6 (Ca5–6)] is shaded in red, the pubocaudalis muscle (origin from the pubic symphysis; insertion on Ca3–4) is purple, and the coccygeus muscle (origin from the ischium; insertion on Ca1–2) is blue. Note that this arrangement of origins and insertions creates a 3-layered crisscrossed meshing of the muscles from their respective pelvic girdle origins, across each other, to their respective Ca1–6 vertebral insertions.

The viscera, as well as striated muscles that serve as true sphincters (urethral and anal rhabdosphincters), are attached to the pelvic floor muscles and each other by connective tissue but do not attach directly to bone. In addition to the urethral and anal rhabdosphincters, striated perineal muscles intimately associated with the viscera include the urethrovaginal sphincter, the compressor urethrae muscle, the ischiocavernosus, and bulbospongiosus muscles (3, 42, 116). In contrast to the levator ani muscles described above, the rhabdosphincter and perineal muscles embryologically develop from the cloaca, with a 2-wk delay in striated muscular differentiation compared with the levator ani and other skeletal muscles (152) and are completely separated from the levator ani muscles by connective tissue (42). Thus, the striated muscles associated with the viscera (i.e., rhabdosphincters) are quite distinct from the striated skeletal muscle of the pelvic floor (e.g., levator ani). It is important to be aware that the urethral rhabdosphincter has historically been referred to by many names, including the external urethral sphincter, the striated urethral sphincter, the striated urethralis muscle, and other names. Recent convention has abandoned the term “external urethral sphincter” because the urethral rhabdosphincter is not really external to the lower urinary tract; it surrounds the middle of the urethra. Therefore, the term “urethral rhabdosphincter,” derived from Latin rhabdo (for striated) and sphincter (to grip tightly), is recommended.

Peripheral Innervation of the Female Levator Ani Muscles

The levator ani muscle of the pelvic floor is innervated by the levator ani nerve in human (Fig. 1A) (4), squirrel monkey (133, 134, 136), dog (175), cat (V. Karicheti and K. B. Thor, unpublished observations), and rat (Fig. 3) (16). The levator ani nerve primarily arises from sacral spinal roots (e.g., S3–S5 in humans) and travels along the intrapelvic face of the levator ani muscle with a high degree of variability in branching patterns (4). In humans, there is some controversy concerning whether or not the pudendal nerve also innervates the levator ani muscle (58, 186). This is not the case in other species (rat, cat, dog, squirrel monkey) where surgical manipulation allows studies to directly examine an innervation of the levator ani muscle by the pudendal nerve. In these animal studies, a number of findings refute an innervation of the levator ani muscles by the pudendal nerve: 1) a marked loss of levator ani muscle mass and a decrease in levator ani myocyte diameter following transection of the levator ani nerve (Fig. 4D) (16, 136) but not after pudendal neurectomy (16, 136); 2) only a single motor endplate zone in the levator ani muscle, located at the point of levator ani nerve insertion into the muscle, is found (Fig. 4, A and B) (16, 136); 3) large α-motor neuron axons (i.e., 10 μm diameter), which are a hallmark of skeletal muscle innervation, are not found in the pudendal nerve (Fig. 5); 4) distinct populations of motor neurons, extremely unique in phenotype, are labeled following application of tracers to the pudendal nerve vs. the levator ani nerve (112, 135, 147, 171, 175, 177, 178); 5) an absence of contractions of levator ani muscles upon electrical stimulation of pudendal nerve efferent fibers (K. B. Thor and V. Karicheti, unpublished observations in cats and rats).

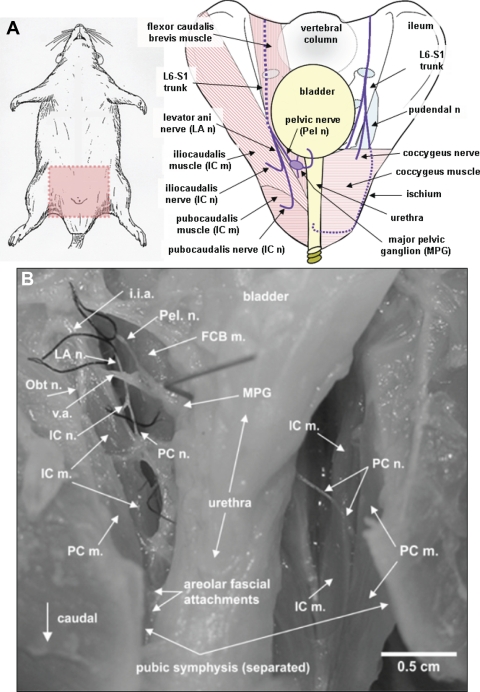

Fig. 3.

A: drawing of rat with pink shaded area (left) as orientation for drawing of female rat pelvis (right). Nerves are shown in purple and their passage behind structures are denoted by dashed lines. The L6-S1 trunk is the origin of the levator ani and pelvic nerves (shown left on the pelvic drawing), which jointly penetrate the pelvic cavity between the flexor caudalis brevis and iliocaudalis muscles. The pelvic nerve then projects ventrally toward the bladder, while the levator ani nerve projects caudally along the plane between the flexor caudalis brevis and the iliocaudalis muscles. The iliocaudalis nerve branches, almost immediately after separation from the pelvic nerve, to penetrate the iliocaudalis muscle, while the pubocaudalis branch continues caudally to penetrate the pubocaudalis muscle. The L6-S1 spinal nerve trunk is also the origin for the pudendal nerve (right on pelvic drawing), which exits the pelvis and travels through the ischiorectal fossa to penetrate the pelvis at the level of the urethral and anal rhabdosphincters. Most of its course is extrapelvic. B: photograph of the pelvis of a female rat showing the relationship between the levator ani nerve and its pubocaudalis and iliocaudalis branches, obturator nerve, pelvic nerve, bladder, and urethra, and the iliocaudalis and pubocaudalis muscles. i.i.a, internal iliac artery; FCB m., flexor caudalis brevis muscle; Obt n., obturator nerve; v.a., vesicular artery; MPG, major pelvic ganglion. [Adapted from Bremer et al. (16).]

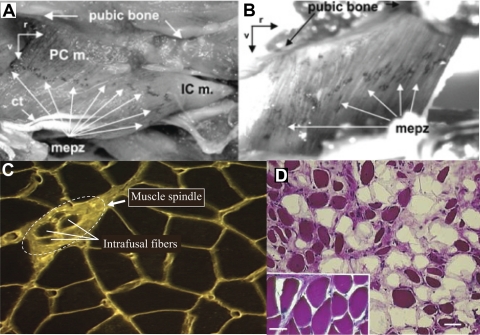

Fig. 4.

A and B: acetylcholine esterase-stained rat pubocaudalis (PCm), iliocaudalis (ICm), and coccygeus muscle (B) showing a single motor end plate zone (mepz) localized to the midpoint of each muscle. Ct, central tendon of ICm; r, rostral; v, ventral. [Adapted from Bremer et al. (16).] C: levator ani muscle from a squirrel monkey stained with wheat germ agglutinin-rhodamine isothiocyanate showing a muscle spindle and associated intrafusal fibers. (L. M. Pierce and K. B. Thor, unpublished). D: hematoxylin and eosin-stained levator ani muscle taken from a squirrel monkey that had a bilateral levator ani nerve transection 2 yr earlier. Note the shrunken, darkly stained muscle fibers and the fat cell infiltration (unstained areas) compared with the healthy muscle fibers from a control animal (inset, same magnification). Despite significant atrophy of levator ani muscle, this animal did not exhibit POP. [Adapted from Pierce et al. (133).]

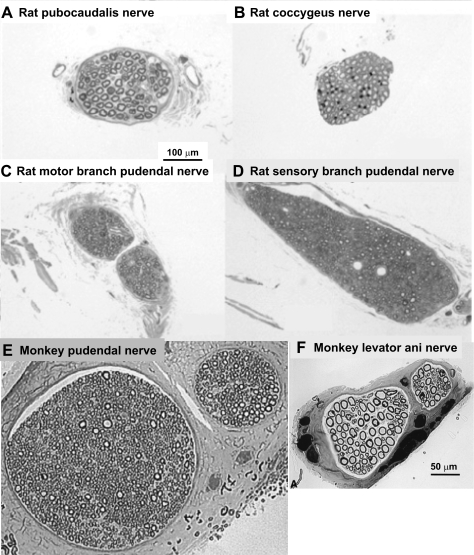

Fig. 5.

Micrographs of toluidine-stained sections of a rat's pubocaudalis (A) and coccygeus (B) branches of the levator ani nerve; rat's motor (C) and sensory (D) branches of the pudendal nerve; monkey pudendal nerve (E); and monkey levator ani nerve (F). Note the preponderance of large, myelinated motor axons (ca. 10 μm diameter) in the levator ani nerve branches and their absence from pudendal nerve branches. Calibration bar in A applies to A–D, while the calibration bar in F applies to E and F. [A–D adapted from Bremer (16); E–F adapted from Pierce et al. (136).]

Thus, divergent techniques support the conclusion that only the levator ani nerve innervates the levator ani muscles with no significant contribution from the pudendal nerve in nonhuman species.

These direct observations, coupled with the vast phenotypic differences between rhabdosphincter pudendal motor neurons in Onuf's nucleus and levator ani motor neurons (described later) and the distinct embryological origins of levator ani muscles vs. rhabdosphincter and perineal muscles [the latter originating from the cloaca (152, 153)], as well as a respective compartmentalization of the rhabdosphincter and perineal muscles by connective tissue (42), are in line with distinct special somatic motor innervation of the rhabdosphincter by the pudendal vs. typical skeletal motor innervation of the levator ani muscle by the levator ani nerve.

The complexity of the perineal region, which consists of a morass of small muscles (puborectalis, compressor urethrae, urethrovaginal sphincter, urethral and anal rhabdosphincter, ischiocavernosus, and bulbocavernosus), blood vessels, connective tissues, and nerves makes dissection, identification, and nomenclature of specific nerve branches and muscles difficult in cadavers. Indeed, this has led to uncertainty regarding even the nomenclature of the muscles themselves (42, 116) and, without extreme care, a contribution of the pudendal nerve to levator ani muscle innervation might be confused. Alternatively, there may be true species differences between humans and other mammals in regard to a minor pudendal nerve contribution to some levator ani muscles (e.g., puborectalis). Possibly a small number of levator ani motor neuron axons travel in the pudendal nerve as an anomaly of development. However, the ability to conduct precise experimental manipulations in animals provides a clear conclusion that the pudendal nerve does not innervate the major muscles of the pelvic floor, i.e., iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, or coccygeus muscles to a significant degree.

The positioning of the levator ani nerve on the intrapelvic surface of the muscles may expose it to damage as the fetal head passes through the birth canal (4) and may contribute to the correlation between parity and POP (3). This positioning may also put it in a favorable position to be activated when current is applied with a St. Mark's electrode placed in the rectum. The positioning of the levator ani nerve, close to the ischial spine, also risks entrapment by sutures used for various suspension surgeries for POP and may account for dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and/or recurrent prolapse (192) associated with such surgery. Finally, since the ischial spine is used as a landmark for needle placement when applying a transvaginal pudendal nerve block (185), the possibility that this procedure also anesthetizes the levator ani nerve and pelvic floor muscles must be considered. These complicating factors of historically accepted clinical concepts may explain why a possible innervation of the levator ani muscle by the pudendal nerve in humans remains controversial.

Detailed anatomical, histological, and physiological studies of the small, intricate muscles of the perineum coupled with studies of their afferent and efferent neurons in humans and larger laboratory species (where they can be readily visualized) is an important area for future research. As a first step, agreements regarding muscle classification should be established in regard to which muscles actually comprise the levator ani or pelvic floor vs. those that are more intimately associated with the viscera. In other words, should pelvic floor muscles include only the skeletal striated muscles such as pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, coccygeus, and puborectalis muscles, while nonskeletal striated muscle such as urethralis, urethrovaginal sphincter, and the compressor urethrae be distinguished from the pelvic floor? Should these latter muscles be considered similar to the urethral and anal rhabdosphincter? Presumably, characteristics of their muscular function, their innervation, their pharmacological responses, or physiological integration with visceral function may allow better understanding of their roles in excretion or sexual function.

Levator Ani Motor Neurons

Retrograde axonal tracing studies involving injection of tracers into the levator ani muscles of cats (184), dogs (175), and squirrel monkeys (135) show that levator ani motor neurons are located in the sacral ventral horn in a longitudinal column. In contrast to the very dense packing of sphincter motor neurons in Onuf's nucleus (112, 147, 171, 177, 178), the levator ani motor neurons are more diffusely distributed (Fig. 6). Furthermore, in contrast to the uniform intermediate size of pudendal motor neurons, levator ani motor neurons show a bimodal distribution of large neurons (presumably α-motor neurons) and small neurons (presumably γ-motor neurons) (Fig. 6C). These two sizes of motor neurons are in keeping with the presence of muscle spindles (whose intrafusal muscle fibers are innervated by γ-motor neurons) in levator ani muscle (Fig. 4C) (57, 131, 136) and the absence of muscle spindles in rhabdosphincter muscle (12, 57, 109, 146, 150, 176); consequently, levator ani may exhibit Ia (muscle spindle)-evoked monosynaptic stretch reflexes, whereas the urethral rhabdosphincter does not (103, 113, 143, 167).

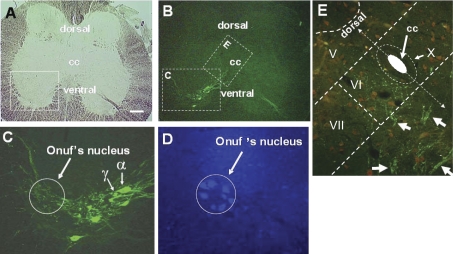

Fig. 6.

A single transverse sacral section of squirrel monkey spinal cord viewed under brightfield (A) and epifluorescence (B–E) illumination to show levator ani (B and C) and anal rhabdosphincter (D) motor neurons in monkey labeled with retrogradely-transported cholera toxin B (CTB) that had been injected into the levator ani muscle (B and C) or fluorogold that had been injected into the anal rhabdosphincter (D). Note the large (α) and small (γ) CTB-labeled levator ani motor neurons identified by arrows with α and γ labels in C. Also note their CTB-labeled processes distributed in Onuf's nucleus in C. Transganglionically-transported CTB in primary afferent terminals (small green dots in E) in medial lamina VI that overlapped with retrogradely-transported CTB in dendritic bundles of levator ani motor neurons (groups of linear arrays of green dots marked with white arrows), allowing for the possibility of monosynaptic connections. Laminae V, VI, VII, and X are indicated. CC, central canal. The size of the white calibration bar in A represents 200 μm for A and B, 20 μm for C, and 50 μm for D and E. [Adapted from Pierce et al. (135).]

Levator ani motor neuron processes (dendrites or axon collaterals) project into two important areas in the sacral spinal cord (Fig. 6) (135). One area, medial lamina VI (Fig. 6E), is where primary afferent fibers from muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs terminate (18, 19). This again suggests an important role for stretch-activated reflex contractions of levator ani muscles. The second projection of levator ani motor neurons is to Onuf's nucleus (Fig. 6, C and D), which contains rhabdosphincter motor neurons. These levator ani motor neuron processes form close appositions with sphincter motor neurons in both monkey (135) and rat (R. E. Bremer and K. B. Thor, unpublished observations). Presumably, these appositions reflect a neuroanatomical substrate for coordination of the rhabdosphincter and the pelvic floor muscles during micturition and defecation. Whether these projections are dendrites designed to receive common afferent input to levator ani and rhabdosphincter motor neurons, or if they are axon collaterals transmitting information from levator ani motor neurons to rhabdosphincter motor neurons to coordinate contractions, is not known and will require electron microscopic or electrophysiological analysis to be resolved.

In rats, it appears that the dendritic arbors of pubocaudalis motor neurons are under the control of gonadal hormones (32). It was shown that ovariectomy reduced the dendritic arbors and that estradiol and progesterone induced an expansion, specifically of the lateral dendritic arbors of the motor neurons.

Levator Ani Afferent Innervation

Afferent levator ani fibers innervate muscle spindles (Fig. 4C) (57, 136) and Golgi tendon organs (131), which are common in skeletal muscles but absent in the rhabdosphincters (12, 57, 109, 146, 150, 176). Dual-label immunohistochemistry combined with cholera toxin B (CTB) tracing studies of the levator ani muscles of squirrel monkeys has shown that there are ∼4 times as many afferent neurons vs. motor neurons labeled following injection of tracer into the levator ani muscle (134). About 25% of the primary afferent neurons are large, myelinated (i.e., RT-97 neurofilament positive) neurons that do not contain the peptide transmitter calcitonin-gene-related peptide, binding sites for isolectin-B4, or the growth factor receptor tyrosine receptor kinase A. Of the remaining small, RT97 negative neurons, ∼50% contain calcitonin-gene-related peptide, isolectin-B4 binding sites, and tyrosine receptor kinase A. It is tempting to speculate that the large, myelinated afferent neurons signal proprioceptive information from muscle spindles (136) and Golgi tendon organs and, in turn, control reflex activity of the levator ani muscles, while the small peptidergic isolectin-B4, tyrosine receptor kinase A-positive neurons transmit nociceptive information. In addition, the large sensory neurons may regulate bladder reflex pathways during ongoing levator ani contractile activity, while the small peptidergic fibers may play a role in bladder hyperreflexia associated with pelvic floor trauma or nerve entrapment by sutures during suspension surgeries.

Transganglionic transport of CTB from the peripheral afferent nerve terminals in the levator ani muscle to their terminals in the spinal cord was only seen in medial lamina VI of the lumbosacral spinal cord (Fig. 6E) (135), an area for termination of large, myelinated proprioceptive terminals (18, 19). The absence of transganglionic CTB labeling in the superficial dorsal horn, which would be expected to contain the central projections of the peptidergic afferent neurons is likely due to an inability of small primary afferent neurons to transport CTB rather than a true absence of levator ani nociceptive terminals in the region. Experiments with a tracer (e.g., horseradish peroxidase) that is transported to nociceptive spinal terminals should be done to confirm this.

Reflex Activation of Pelvic Floor Muscles

There is not much information regarding reflex control of pelvic floor muscles associated with visceral function (e.g., micturition). A recent study in rabbit (30) showed that during bladder filling (i.e., the storage phase) the pubococcygeus muscle was active, while during micturition it was quiet. The same study showed the opposite relationship for the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles, which were silent during bladder filling but active during micturition. Importantly, the rabbit, like cat and human, shows virtually complete inhibition of the sphincter during micturition, while the rat rhabdosphincter shows a high-frequency bursting of the urethral rhabdosphincter during micturition that is important for efficient voiding in this species.

One study in the male rat (108) indicated that the pubocaudalis muscle is active during bladder contractions and shows high-frequency bursting like the urethral rhabdosphincter EMG. Preliminary studies (S. Mori and K. B. Thor, unpublished observations) in female rats also indicated that the pelvic floor muscles can be activated during a micturition contraction (Fig. 7). These studies revealed that pubocaudalis EMG activity increased during a micturition contraction in 50% of the rats under control conditions. The remaining rats showed micturition-associated pubocaudalis EMG activity after administration of various drugs (e.g., α2-adrenoceptor antagonists) known to enhance motor neuron reflexes (51).

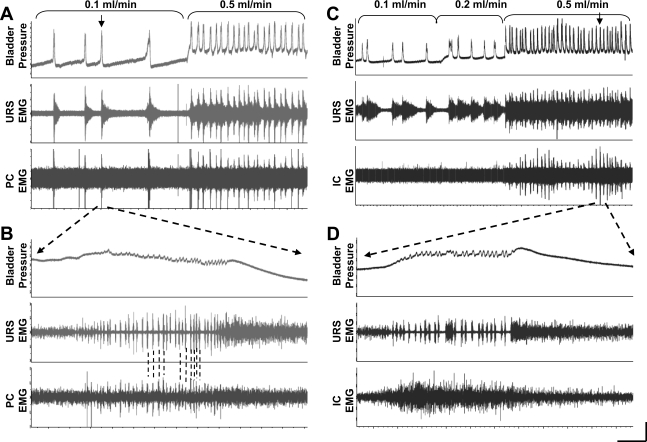

Fig. 7.

Examples of pubocaudalis (PC; A and B) and iliocaudalis (IC; C and D) EMG activity during continuous filling cystometry in female rats. Top tracing: bladder pressure; middle tracing: urethral rhabdosphincter (URS) EMG activity; and bottom tracing: PC (A and B) or IC (C and D) EMG activity. The rate of bladder infusion was increased from 0.1 to 0.5 ml/min (A) and 0.1 to 0.2 to 0.5 ml/min (C) as indicated by the brackets. A: note that the URS activity increases preceding the bladder contraction and the activity is maintained for a period of ∼30 s after the contraction, while the PC EMG is only active during the bladder contraction. Increasing the infusion rate produces continuous activity of the URS, while the PC is activated only during the bladder contraction. B: the contraction marked by the arrow in A is at a faster time scale. Note the characteristic phasic bursting pattern of the URS EMG during the high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) of the bladder pressure. Note that the PC EMG also shows phasic activity during the bladder contraction that is temporally correlated with the URS bursting (indicated by dashed lines). C: from a different rat, activity in the IC is not detectable during bladder contractions until the bladder infusion rate is increased to 0.5 ml/min, when the IC EMG is consistently activated with each bladder contraction at the same time as the URS EMG. D: the contraction marked by the arrow in A is at a faster time scale. Note that in contrast to the bursting pattern of the URS during the bladder HFOs that the IC EMG shows only asynchronous, tonic activity with no evidence of bursting. Horizontal calibration bar = 75 s for A and C and 0.5 s for B and D. Vertical calibration bar = 0.5 mV for URS EMG and 0.1 mV for PC and IC EMG, and 15 cm H2O bladder pressure.

The pubocaudalis muscle EMG was always smaller (∼80% less) than the urethral rhabdosphincter EMG and was only elicited by a faster bladder filling rate, indicating that the pubocaudalis reflexes require a stronger afferent drive from the bladder than rhabdosphincter reflexes (Fig. 7A). The micturition-related pubocaudalis EMG activity exhibited phasic, high-frequency bursting (characteristic of the rat rhabdosphincter micturition-associated EMG) but were much less prominent (dashed lines in Fig. 7B). Furthermore, the pubocaudalis muscle exhibited very little activity preceding or following a bladder contraction, while the rhabdosphincter EMG showed an increase in asynchronous activity immediately preceding a micturition contraction and an even larger increase in asynchronous activity immediately after the micturition contraction. Thus, although there are some similarities in pubocaudalis and rhabdosphincter EMG activity, there are also distinctions that suggest separate but possibly overlapping control mechanisms.

The iliocaudalis muscle also exhibited an increase in EMG activity during bladder contractions (Fig. 7C) in 60% of the rats. However, in these rats the iliocaudalis activity never showed phasic bursting activity during micturition and instead showed only an asynchronous tonic discharge (Fig. 7D). Even after facilitatory drug treatments, when the iliocaudalis activity was strongest, no bursting was observed. To evoke iliocaudalis EMG activity during a bladder contraction, the infusion rate of the bladder had to be increased, and the signal was again smaller than the rhabdosphincter EMG signal. Thus, both the iliocaudalis and pubocaudalis appear to have a weaker activation from bladder pathways than the rhabdosphincter. The pubocaudalis muscle exhibits a weak phasic bursting pattern during micturition (similar but weaker than that of the urethral rhabdosphincter), while the iliocaudalis shows only asynchronous, tonic firing during micturition.

One should not conclude from these studies in rats that similar relationships between visceral and pelvic floor activity exist in humans since the pubocaudalis and iliocaudalis muscles are important in controlling the tail of rats. Thus the EMG activity during micturition may simply be involved in positioning the tail during micturition. Regardless, reflex control of pelvic floor activity during micturition, defecation, and copulation is an area for additional research.

Levator Ani Innervation Damage in Childbirth and POP

Childbirth is a risk factor for development of POP (37). Furthermore, various studies have indicated damage to the innervation of the pelvic floor muscles, which might be expected to initiate pelvic descent and prolapse (1, 157, 158, 160, 161, 189). Early studies using pudendal nerve terminal latency as a measure of nerve damage (159) were met with skepticism for many reasons; however, with more sophisticated analyses using EMG interference patterns, a more recent series of elegant studies (161, 188–191) have provided evidence that levator ani nerve damage accompanies parturition in ∼25% of women with approximately one-third of those continuing to show evidence of nerve damage at 6 mo after parturition (161). Importantly, women undergoing elective cesarean section (i.e., without preceding labor) showed no signs of levator ani nerve damage, while damage occurred in similar proportions of women who had cesarean section after protracted labor as those without cesarean section (189). Furthermore, changes in function of the urethral rhabdosphincter were also associated with pregnancy (i.e., before labor), and these remained evident at 6 mo postpartum (191). In rabbits (47), it has also been shown that multiparous females have thinner, longer, and weaker pubococcygeus muscles than nulliparous females, which may indicate nerve damage also occurs in this species.

Because the pelvic floor is responsible for providing support of the viscera and because one might expect contraction of pelvic floor muscles to be necessary for adequate support, damage to the levator ani innervation and subsequent muscle flaccidity was thought to promote POP. To test this expectation, the levator ani muscles were bilaterally denervated in seven squirrel monkeys (133), which is a species that shows age- and parity-correlated POP similar to humans (28). Surprisingly, these monkeys showed no POP following this procedure for 2–3 yr after surgery, despite showing statistically significant decreases in levator ani muscle mass and myocyte diameter (Fig. 4D). However, a slight increase in bladder and cervical descent with abdominal pressure was seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation compared with nulliparous controls. Of possible significance was the finding that, after a single birth, 2 of 4 animals with bilateral levator ani neurectomy uncharacteristically showed POP. A larger study is needed to confirm whether levator ani nerve damage may accelerate parity-related POP.

Thus, these experiments indicate that, in the absence of childbirth, the pelvic floor muscle plays a minor role in providing visceral support and suggests that the connective tissue plays the major role. Thus, future research might focus more specifically on the changes in pelvic ligaments or extracellular matrix that occur with pregnancy, childbirth, and aging. Possibly after childbirth and stretching of the pelvic connective tissue, the muscle plays a compensatory role. In support of this possibility, it was shown that levator ani muscle mass and myocyte diameter in monkeys with naturally occurring POP was equal to or greater than age-, parity-, and weight-matched monkeys without POP (88, 133), suggesting that levator ani muscle stretching might induce reflexes and subsequent muscle activity and hypertrophy.

Peripheral Innervation of Urethral and Anal Rhabdosphincters

At the level of the pelvic floor, the urethra and anal canal are surrounded by bands of striated muscle fibers (the urethral and anal rhabdosphincters, respectively). The muscles do not have dedicated attachments to skeletal structures and thus act as true sphincters (i.e., contraction produces virtually no movement except constriction of the lumen). In addition, there are small, thin bands of striated muscle (compressor urethra, urethrovaginal sphincter, bulbocavernosus, ischiocavernosus) that surround the urethra, vagina, and/or rectum and have connective tissue attachments to the perineal body (3).

Extensive studies of the urethral rhabdosphincter, anal rhabdosphincter, bulbocavernosus, and ischiocavernosus muscles have shown that these muscles are innervated by the pudendal nerve (4, 112, 129, 130, 147, 171, 177, 178), which originates from the S2-S4 sacral roots in humans and passes along the lateral surface of the internal obturator and coccygeus muscles and through Alcock's canal (Fig. 1B). As the nerve passes through the canal, it branches into the inferior rectal nerve (which innervates the anal rhabdosphincter), the perineal nerve (which innervates urethral rhabdosphincter, the bulbospongiosus muscle, the ischiocavernosus muscle, superficial transverse perineal muscle, labial skin), and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris. The branches of the perineal nerve are more superficial than the dorsal nerve of the clitoris and, in most cases, travel on the superior surface of the perineal musculature. The terminal branch of the perineal nerve to the striated urethral sphincter travels on the surface of the bulbocavernosus muscle and then penetrates the urethra to innervate the sphincter from the lateral aspects (Fig. 1B). The specific innervation of the smaller bands of muscles attached to the perineal body has not been characterized.

The nerve fascicles (79), as well as the motor nerve terminals and end plates (137) of the urethral rhabdosphincter, are preferentially located along the lateral aspects of the urethra in rat. Overlap, or crossing of the midline, between the left and right pudendal nerve terminal fields has been described in monkey anal rhabdosphincter (193). The rhabdosphincter of both men and women contain neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), which is contained in a subpopulation (43%) of the muscle fibers, as well as nerve fibers, with concentration at the neuromuscular junction in humans and sheep (56, 62, 63). Additionally, nNOS has been localized to pudendal motor neurons, which innervate the rhabdosphincter in rats, cats, monkeys, and humans (138, 139). nNOS is responsible for producing the transmitter NO. While NO is known to increase cGMP levels in many types of smooth muscle, its role in control of striated muscle and in neuromuscular transmission is not well established (162). An NO donor has been shown to reduce urethral pressures at the level of the rhabdosphincter (145), but it is difficult to determine whether the effect is on smooth or striated muscle.

Early histological studies raised the possibility that the urethral rhabdosphincter receives a triple innervation from somatic, parasympathetic, and sympathetic nerves (45). However, this has been disputed by subsequent studies (31) that showed no physiological effects of autonomic nerve stimulation on striated sphincter function and showed that the autonomic fibers are only passing through the outer layer of striated muscle to reach the inner layers of smooth muscle.

Urethral and Anal Rhabdosphincter Motor Neurons

Extensive hodological studies locate pudendal motor neurons that innervate the urethral and anal rhabdosphincters (and bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus) muscles along the lateral border of the sacral ventral horn in Onuf's nucleus (Figs. 6–8) in human (128), monkey (123, 147), dog (175), cat (148, 171, 178), hamster (53), and guinea pig (93). Studies in cat (171), monkey (147), and human (128) show that urethral rhabdosphincter motor neurons occupy a ventrolateral position and anal rhabdosphincter motor neurons occupy a dorsomedial position within the confines of Onuf's nucleus (Figs. 6, 8, and 9, A, B, and E).

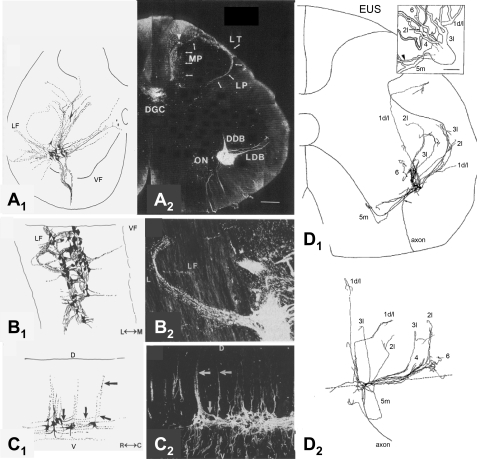

Fig. 8.

A–C: composite drawings (A1–C1) and photomicrographs (A2–C2) of pudendal motor neurons in cat labeled by application of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to the pudendal nerve as seen in transverse (A), horizontal (B), and sagittal (C) sections. The photographs provide raw data from 1 of the single sections used to make the corresponding composite drawing. Note that the dendrites of pudendal motor neurons project into the lateral funiculus (LF). D, dorsal; V, ventral; M, medial; L, lateral; R, rostral; C, caudal. Primary afferent terminal labeling can also be seen in Lissauer's tract (LT), the lateral pathway (LP), medial pathway (MP), and dorsal gray commissure (DGC) in A2. (Primary afferents were not drawn in A1, only motor neurons.) DDB, dorsal dendritic bundle; ON, Onuf's nucleus; LDB, lateral dentritic bundle. [Adapted from Thor et al. (171).] D: composite drawing of a single pudendal motor neuron labeled by intracellular injection of HRP showing the transverse (D1) and sagittal (D2) distribution of dendrites (1 d/l, 2l, 3l, 5m). The dashed line in D2 represents the border between the ventral horn and ventral funiculus. Inset in D1 is a 3-D rendition of the neuron. EUS, external urethral sphincter. The arrowhead indicates the cell's axon. [Adapted from Sasaki (148).]

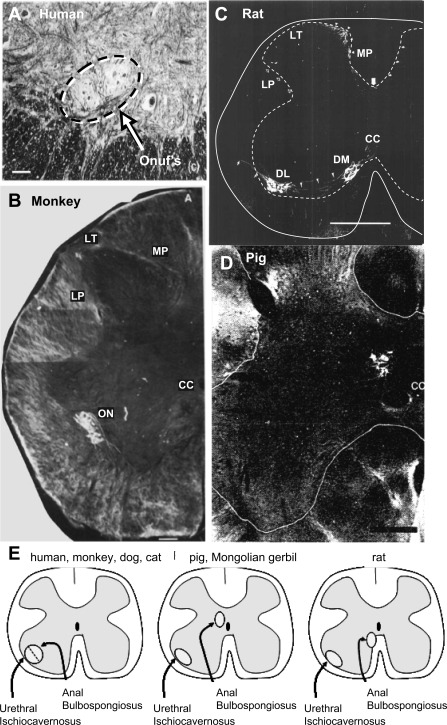

Fig. 9.

Interspecies variability in location of anal rhabdosphincter and bulbospongiosus motor neurons in human (A), monkey (B), rat (C), and pig (D). [Adapted from McKenna and Nadelhaft (112), Onufrowicz (128), Roppolo et al. (147), and Blok et al. (9)] C: solid line outlines the spinal cord and dashed line outlines gray matter. E: diagram showing the different distributions of anal and bulbospongiosus motor neurons in various species compared with the similar distribution of urethral and ischiocavernosus motor neurons across species. In D, only the anal rhabdosphincter motor neurons were labeled with retrograde tracer. LT, Lissauer's tract; MP, medial pathway of pudendal afferent fibers; LP, lateral pathway of pudendal afferent fibers; ON, Onuf's nucleus; CC, central canal; DM, dorsomedial nucleus of the pudendal nerve; DL, dorsolateral nucleus of the pudendal nerve. Bars: A = 100 μ; B = 200 μ; C = 500 μ; D = 300 μ.

However, in other species, urethral and anal rhabdosphincter motor neurons are located in separate nuclei. In rat (112), anal sphincter (and bulbospongiosus) motor neurons are located medially in the ventral horn, just ventrolateral to the central canal, while the urethral sphincter (and ischiocavernosus) motor neurons are located in the same region as others species, i.e., along the lateral edge of the ventral horn (Fig. 9, C and E). In the domestic pig (Fig. 9D) (9) and Mongolian gerbil (179), anal sphincter (and bulbospongiosus) motor neurons are located just dorsolateral to the central canal (Fig. 9E).

Sphincter motor neurons are different from motor neurons that innervate skeletal muscles. They are densely packed within the confines of Onuf's nucleus and exhibit tightly bundled dendrites that run rostrocaudally within the confines of the nucleus. Transverse dendrites are particularly unique in bundling and projecting laterally into the lateral funiculus, dorsally toward the sacral parasympathetic nucleus, and dorsomedially toward the central canal (Fig. 8) (5, 148, 171). This is similar to dendritic projections of bladder preganglionic neurons (121) and very different from that of limb motor neurons, suggesting that rhabdosphincter motor neurons and preganglionic neurons receive inputs from similar regions of the spinal cord. It has been suggested that the dense packing and dendritic bundling of sphincter motor neurons may be related to their special sphincteric function and may facilitate simultaneous activation of all sphincter motor units. Recurrent axon collaterals (Fig. 8D) (148) in the absence of recurrent inhibition (72, 103) suggests a recurrent facilitation that may also reinforce simultaneous activation. Because the rhabdosphincters are not attached to bone, efficient closure of the sphincter requires symmetrical contraction of all motor units simultaneously, i.e., partial contraction in one part of the circle would be defeated by relaxation in another part, like squeezing a balloon only on one side. It has been suggested that the arrangement of somatic motor nerve terminals bilaterally at dorsolateral and ventrolateral positions in the urethra provides symmetrical activation and force generation (137).

In addition to their unique morphology, rhabdosphincter motor neurons are also physiologically distinctive from skeletal muscle motor neurons in that they do not exhibit significant monosynaptic inputs (103), Renshaw cell inhibition (103), nor crossed disynaptic inhibition (72). The passive membrane properties [e.g., high input resistance, low rheobase, short afterhyperpolarization, membrane bistability, nonlinear responses to depolarizing current injection, which was recently reviewed (154)] are uniquely conducive to simultaneous, prolonged, tonic activity, in keeping with the anatomical and functional properties described above.

Afferent Innervation of the Urethral and Anal Rhabdosphincters

Various studies have characterized primary afferent neurons sending axons into the pudendal nerve (76, 112, 171). However, this nerve carries the innervation to many visceral structures (e.g., urethra, genitalia, rectum, vagina) in addition to skin and rhabdosphincters, thus it is difficult to specifically characterize the sensory innervation of the sphincters per se. Nevertheless, the paucity of large sensory neurons in sacral dorsal root ganglia following application of tracers to the pudendal nerve suggests that the sensory innervation of the rhabdosphincters does not contain large fiber sensory endings such as muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs, or Pacinian corpuscles. Furthermore, multiple investigators using various techniques have not found muscle spindles or Golgi tendon organs in the rhabdosphincters nor that the pudendal nerves contain large myelinated fibers (i.e., Type Ia and Ib) that innervate these sensory organs (12, 57, 109, 146, 150, 176). This is consistent with the finding that the pudendal nerves lack small γ-motor neuron axons (which innervate muscle spindles) (146) and the absence of rhabdosphincter connections to bone by tendons. On the other hand, Pacinian corpuscle-like structures have been found in the urethra of cat (176) and may play a role in sensing urine flow during micturition to inhibit sphincter activity and/or reinforce detrusor contractions.

The spinal terminals of pudendal primary afferent fibers are distributed throughout laminae I, V, VII, and the dorsal gray commissure (Fig. 8A2), while labeling in laminae III and IV is well-defined and restricted to the medial third of the dorsal horn. This restricted pattern in laminae III and IV is consistent with the somatotopic organization expected for cutaneous mechanoreceptors originating in the perineal skin (82). Local injection of horseradish peroxidase targeted to the urethral and anal rhabdosphincters (171) or injections of CTB into the urethral rhabdosphincter (36) (Fig. 10) only produced labeling of the spinal terminals of primary afferent neurons in lateral and medial lamina I, the intermediate gray matter, and the dorsal commissure gray matter, not in laminae III or IV. Since the horseradish peroxidase likely spread into the urethra and rectum, it is possible that this labeling occurred in visceral as well as rhabdosphincter afferent pathways. However, since no labeling was seen in large-diameter, primary afferent neurons nor in terminals in medial laminae III and IV (cutaneous fields) nor medial lamina VI, an area where large-diameter myelinated fibers of muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organs nerves terminate (18, 19), it is reasonable to conclude that the rhabdosphincters are not significantly innervated by large myelinated nerve fibers typically associated with other striated muscle.

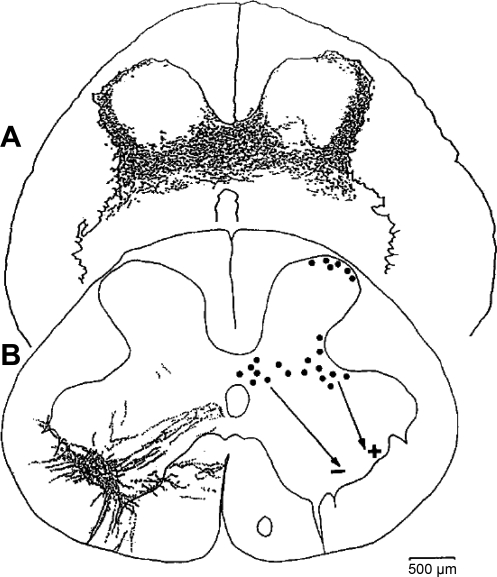

Fig. 10.

A: distribution of afferent projections in the S1 section of the spinal cord from the EUS muscle of the cat. Afferents labeled by anterograde transport of choleratoxin-B-HRP. Composite drawing showing labeled afferent nerves in 5 sequential sections (56 mm thickness) representing an axial distance of 280 mm. B, left: distribution of EUS motor neuron dendrites in the S1 section of cat spinal cord. Neurons were labeled by retrograde transport of choleratoxin-B-HRP. Right: distribution of pseudorabies virus (PRV)-infected interneurons in the S1 section of the spinal cord after injection of PRV into the EUS of the cat. It is likely that lateral interneurons provide an excitatory input (+) and medial interneurons in the dorsal commissure provide an inhibitory input (−) to sphincter motor neurons. [Adapted from de Groat (36).]

Reflex Activation of Urethral and Anal Rhabdosphincters

Rhabdosphincter motor neurons can be activated via segmental (15, 103, 113, 142, 143) and descending pathways (67, 103, 115). The segmental inputs can be activated by stretch receptors and nociceptors in the bladder or urethra or genitalia (13, 26, 168, 172). Electrophysiological studies in cats (15, 33, 113, 142, 143, 167, 171) show that stimulation of either pelvic nerve or pudendal nerve afferent fibers can activate polysynaptic spinal segmental reflexes that can be recorded at central delays of 1.5 ms with intracellular electrodes in sphincter motor neurons (48, 49) and at a latency of about 10 ms from electrodes placed on pudendal nerve efferent fibers or inserted directly into the urethral or anal rhabdosphincter muscles (167) (Figs. 11–14). The segmental reflex is considered polysynaptic based on the latency (48, 49, 102) and retrograde transynaptic labeling of interneurons in laminae I and V of the dorsal horn and in the dorsal gray commissure by pseudorabies virus injected into the urethral rhabdosphincter (Fig. 10) (36). The dorsal horn interneurons are likely those that participate in the segmental reflex activation of sphincter motor neurons, while the dorsal gray commissure interneurons are likely inhibitory (see Inhibition of Urethral Rhabdosphincter Reflexes During Voiding). Studies in rats also show that electrical stimulation of afferent axons in the pelvic nerve elicits reflexes in pudendal nerve efferent fibers or the urethral rhabdosphincter (23, 111) similar to the cat. Also similar to the cat, pseudorabies virus injected into the urethral rhabdosphincter (122) labels interneurons in laminae I and V of the dorsal horn and in the dorsal gray commissure.

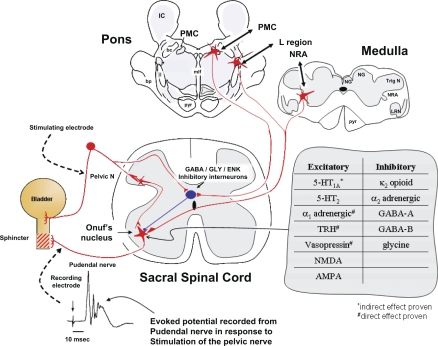

Fig. 11.

Drawing of proposed model for spinal and supraspinal excitation and inhibition of rhabdosphincter pudendal motor neurons with an example of the evoked potential recorded by an electrode on the pudendal nerve in response to electrical stimulation of the pelvic nerve at 0.5 Hz and a table showing the predominant effects of various receptor subtypes on evoked potentials recorded from the pudendal nerve or urethral rhabdosphincter. Red stellate shapes and lines represent excitatory neurons and their axonal pathways, respectively, while the black oval shape and line represent an inhibitory interneuron and its axonal pathway. Stimulation of the pelvic nerve activates a polysynaptic spinal reflex arc that produces an evoked potential recorded from axons of sphincter motor neurons in Onuf's nucleus at a latency of about 10 ms. In addition, this stimulation also activates inhibitory interneurons that, after 50 ms delay, produce inhibition of sphincter motor neurons for ∼1,000 ms (see Inhibition of Urethral Rhabdosphincter Reflexes During Voiding for details). Presumably this arrangement allows low-frequency pelvic afferent activity (1 Hz) to increase sphincter activity during urine storage and to inhibit sphincter activity when the pelvic afferent activity markedly increases (>5 Hz) as might occur with very large bladder volumes or during a micturition contraction. The model includes GABAergic, glycinergic, or enkephalinergic inhibitory neurons located in the dorsal gray commissure. In addition to spinal excitatory sphincter reflexes, supraspinal pathways originating in the medullary nucleus retroambiguus (NRA) and the pontine L region can activate sphincter motor neurons during Valsalva maneuvers and during urine storage, respectively. When micturition occurs, neurons in the pontine micturition center (PMC) provide descending activation of the GABAergic, glycinergic, or enkephalinergic neurons in the dorsal gray commissure to inhibit sphincter motor neurons and allow voiding to begin. In addition to these predominant pathways, various other areas of the brain (e.g., medullary raphé serotonergic pathways, pontine locus coeruleus noradrenergic pathways, etc.) provide “modulation” of the reflexes. Those excitatory and inhibitory modulatory pathways that have been explored pharmacologically are also listed in the table. For simplicity, the inhibition associated with PMC activation and the inhibition associated with pelvic nerve stimulation are shown passing through the same inhibitory interneuron. However, no evidence yet exists that this is the case. Details and references are in the text and Table 2. Abbreviations: IC, inferior colliculus; NG, nucleus gracilis; NC, nucleus cuneatus; TrigN, spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve; LRN, lateral reticular nucleus; pyr, pyramidal tract; mlf, medial longitudinal fasciculus; ll, lateral lemniscus; bc, brachium conjunctivum; bp, brachium pontis; GABA, γ-amino butyric acid; GLY, glycine; ENK, enkephalin; TRH, thyrotropin releasing hormone; NMDA, N-methyl d-aspartate; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

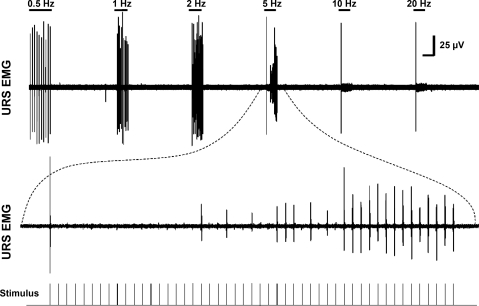

Fig. 14.

Example of frequency-response relationship of the URS potentials evoked by pelvic nerve stimulation (top trace). Note the decreased amplitude of the evoked reflex potentials to frequencies ≥ 5 Hz. Bottom trace: 5 Hz stimulation at faster sweep speed. Note the large amplitude reflex evoked by the first stimulus and complete failure of the 2nd–19th evoked responses. Vertical calibration bar = 25 μV. Horizontal calibration bar = 10 s in upper trace and 0.33 s in lower trace.

Previously, the afferent inputs from the urinary bladder have been emphasized as being of primary importance for activation of the segmental reflex by pelvic nerve stimulation (Figs. 11 and 12) because bladder distension will activate the urethral rhabdosphincter (74). This reflex activation is often referred to as the guarding reflex or continence reflex. However, recent studies are placing greater emphasis on urethral afferent fibers (26, 71, 172). It is tempting to speculate that the guarding reflex is actually activated more vigorously by urethral afferent fibers if urine inadvertently begins to pass through the bladder neck and into the proximal urethra, with a requirement for a rapid closure of the more distal urethral sphincter (i.e., guarding against urine loss) compared with simple bladder distension or increases in intravesical pressure.

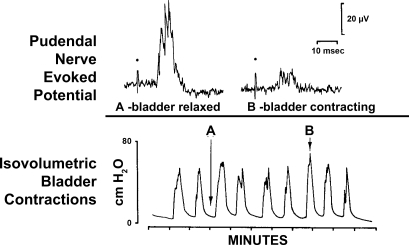

Fig. 12.

Example of the coordinated inhibition of pudendal reflexes during a bladder contraction. Top: tracings are computer-averaged evoked potentials recorded from the pudendal nerve in response to electrical stimulation (dots) of the pelvic nerve after a latency of 10 ms. Bottom: tracing is recording of bladder pressure under isovolumetric conditions. Note the decreased amplitude of evoked potential B taken during a bladder contraction (at arrow B above bladder pressure tracing) compared with evoked potential A taken between bladder contractions (at arrow A above bladder pressure tracing). [Adapted from Thor et al. (167).]

The greater importance of urethral afferent fibers is also suggested by experiments where bladder afferent fibers are electrically stimulated. For example, in studies by McMahon et al. (113), electrical stimulation of pelvic nerve fibers close to the bladder was not able to evoke pudendal nerve firing in a large proportion of cats but placement of electrodes more centrally on the pelvic nerve was able to evoke firing. V. Karicheti and K. B. Thor (unpublished observations) also found that stimulating nerve bundles close to the bladder is often ineffective in producing a spinal reflex to the urethral rhabdosphincter, but in the same animals it evokes reflex activity on the hypogastric nerve (indicating that the electrical stimulation is activating bladder afferent fibers). Furthermore, it was possible to consistently evoke a reflex when the stimulus was applied more centrally on the pelvic nerve, which would include fibers from the urethra. Since the more central electrode placement would also activate colonic and genital afferent fibers, additional experiments are needed to specifically compare urethral vs. bladder vs. colonic afferent fibers in evoking the guarding reflex.

Electrical stimulation of pudendal afferent fibers also evokes a spinal reflex to activate the rhabdosphincter in cat (35, 113, 132) and rat (23, 111). Since some urethral afferent fibers (as well as rectal, genital, and cutaneous afferent fibers) travel in the pudendal nerve, it is possible that the spinal urethral rhabdosphincter activation by pudendal afferent stimulation is also a manifestation of the guarding reflex.

Sphincter reflexes in the cat also exhibit prolonged changes in excitability following short trains (5–10 s) of electrical stimulation of afferent axons in the pudendal nerves (132). Recordings from sphincter motor neurons in the sacral spinal cord and from rhabdosphincter peripheral motor axons revealed that stimulation of pudendal afferent axons elicited not only short latency transient responses but also sustained activity persisting for 3–30 s after the end of the stimulus train (132). The persistent activity was associated with a small membrane depolarization and was terminated by small hyperpolarizing currents. Similar persistent activity has been observed in hindlimb motor neurons with slow axonal conduction velocities similar to those of sphincter motor neurons (94, 95). In hindlimb motor neurons, the persistent firing has been attributed to intrinsic properties of the neurons mediated by a prolonged inward current that imparts a negative slope region to the steady-state I-V function (151). This current is mediated by noninactivating l-type Ca2+ channels that generate plateau potentials and bistable firing behavior (69, 70). 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) or a 5-HT precursor that facilitates limb as well as sphincter reflexes (see below) unmasks or enhances bistable activity in hindlimb motor neurons (69). Evidence for similar channels in cat sphincter motor neurons was obtained using intracellular recording (132), which revealed 1) a persistent low-amplitude membrane depolarization in response to a transient depolarizing current pulse and 2) a nonlinear response during membrane depolarization that occurred at a threshold (−43 mV) similar to that for the persistent inward current observed in hindlimb motor neurons. Thus brief excitatory inputs to sphincter motor neurons can open noninactivating cation channels and induce a persistent membrane depolarization and sustained firing that could contribute significantly to maintenance of continence.

Inhibition of Urethral Rhabdosphincter Reflexes During Voiding

Voiding is induced voluntarily or reflexively by neural circuitry in the brain (50). For voiding to occur, there must be contraction of the bladder and simultaneous relaxation of the urethral rhabdosphincter. These responses are mediated by descending projections from neurons in the pontine micturition center that excite the sacral autonomic outflow to the bladder and inhibit the motor outflow to the sphincter (Fig. 11). Thus inhibition of the sphincter during micturition is readily observed in humans and cats (Fig. 12) when the central nervous system is intact or after removal of the forebrain by midcollicular decerebration but is markedly reduced following spinal cord injury (50). Electrical or chemical stimulation in the pontine micturition center in cats excites the bladder and inhibits sphincter EMG activity (36, 66, 91, 105, 106) and hyperpolarizes sphincter motor neurons (132). The latency for inhibition of sphincter EMG activity following pontine micturition center stimulation is ∼50 ms (91). The descending inhibitory pathway from the pontine micturition center to sphincter motor neurons is thought to involve spinal GABAergic inhibitory neurons in the dorsal commissure of the sacral spinal cord (Figs. 8–10). A role for glycinergic and enkephalinergic interneurons in the dorsal commissure has also been proposed (8, 10, 36, 87, 155, 156) in mediating inhibition of the sphincter during voiding (Fig. 11).

In addition to supraspinal inhibitory mechanisms, a spinal, urine storage reflex, inhibitory center (SUSRIC) was found that inhibited both the somatic and the sympathetic urine storage reflexes controlling the urethral rhabdosphincter and smooth muscle, respectively, in the cat (75, 170). Activation of this inhibitory center by electrical stimulation of the pelvic nerve afferent fibers occurs simultaneously with the activation of the urethral rhabdosphincter reflex itself, at a latency of < 50 ms and a duration of > 500 ms (Fig. 13, A and D). Activation of this inhibitory center explains the diminished capacity of the urethral rhabdosphincter-evoked reflex to follow frequencies of pelvic afferent stimulation > 5 Hz (Fig. 14) (75). Physiological stimulation of the pelvic nerve afferent fibers, which occurs with distension of the bladder, has also been reported to inhibit rhabdosphincter EMG activity in both spinal intact (143) and spinalized cats (142) in the absence of a bladder contraction and its associated inhibitory mechanisms. Possibly the inhibition of rhabdosphincter activity by distension of the bladder represents a physiological corollary for the inhibition of rhabdosphincter activity by high-frequency electrical stimulation of pelvic nerve afferent fibers. Although the inhibitory effects are localized to the spinal cord caudal to the T12 level, they are regulated by supraspinal systems that respond to 5-HT1A receptor activation and enhance sphincter activity through disinhibition (Fig. 13) (60, 61, 169). A possible clinical correlation of SUSRIC activation may be the elegant demonstration in men that conditioning stimuli applied to the dorsal nerve of the penis (i.e., pudendal nerve afferent fibers) inhibited urethral rhabdosphincter contractions reflexively evoked by magnetic stimulation of the spinal cord applied at intervals of 20–100 ms after the conditioning stimuli (187).

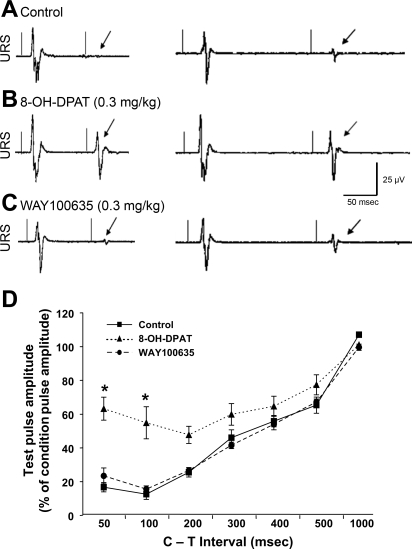

Fig. 13.

Condition-test (C-T; paired-pulse) inhibition of pelvic (PEL) nerve-evoked potentials recorded from URS EMG electrodes. A–C: evoked potentials recorded at interstimulation intervals of 100 ms (left tracings) and 200 ms (right tracings) during control (A) and after the 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-OH-DPAT (B) and the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY100635 (C). Each trace is an average of 10 sweeps from a single animal with drugs administered sequentially. The 2 thin vertical lines on each trace represent the conditioning (first) and test (second) stimuli applied to the pelvic nerve. Note that during the control period at 100 ms, the second stimulus pulse produces virtually no PEL-URS reflex (single arrow at latency for expected evoked potential), while at 200 ms a very small PEL-URS reflex (single arrow) can be seen. Note that 8-OH-DPAT (0.3 mg/kg iv) has modest effects on the amplitude of the conditioning (first) evoked potential but greatly augments the amplitude of the test (second) evoked potential at both 100 and 200 ms interstimulation intervals. Note that WAY100635 (0.3 mg/kg iv) reverses the effect of 8-OH-DPAT. D: graph showing the effects of increasing the C-T interstimulus intervals on the amplitude of the potential evoked by the test (second) stimulus expressed as a percentage of the conditioning (first) stimulus. Recordings were obtained before drugs (control, solid line with squares), after 0.3 mg/kg 8-OH-DPAT (dotted line with triangles), and after WAY100635 (dashed line with circles). *Note that 8-OH-DPAT significantly reduced the inhibition of the conditioning stimulus at the 50 and 100 ms interstimulus intervals, and this effect was completely reversed by WAY100635.

Supraspinal Activation of Rhabdosphincters and Pelvic Floor Muscles

Supraspinal activation of urethral and anal rhabdosphincter motor neurons can be mediated in response to voluntary [i.e., corticospinal (123)], as well as involuntary reflexic inputs (e.g., during coughing, sneezing, vomiting), presumably from nucleus retroambiguus in the caudal medulla (Fig. 11) (11, 73, 74, 115, 117–119, 182, 183). Nucleus retroambiguus also innervates the pelvic floor muscles (182, 183), as well as abdominal muscles, consistent with a role in raising intra-abdominal pressure during Valsalva maneuvers. Generally, the pelvic floor and rhabdosphincter muscles are activated as a functional unit when voluntarily contracted. However, differential activation of the rhabdosphincter and the pelvic floor muscles has been demonstrated (78), indicating distinct CNS control systems and innervation. Clinical EMG recordings show that even during sleep, activity can be recorded from specific rhabdosphincter motor units (46).

Rhabdosphincter motor neurons are unique among somatic motor neurons in receiving input from the paraventricular hypothalamus (67), although the function of this input has not been determined. In addition, their input from brain stem serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons is among the most dense in the spinal cord (83–85, 140). Finally, rhabdosphincter motor neurons also receive input from the “L region” of the pons that might be important for maintaining continence, since a lesion in this area produced continuous incontinence in a cat (66).

Relative Contribution of Levator Ani and Pudendal Nerves to Continence Mechanisms During Sneezing in Rats and Cats

Analysis of the urethral closure mechanisms during sneeze-induced stress conditions in anesthetized female rats and cats has revealed that pressure increases in the middle portion of the urethra are mediated by reflex contractions of the rhabdosphincter as well as the pelvic floor muscles (6, 74). Transection of the pudendal nerves reduced sneeze-induced urethral reflex responses by 67%, and transecting the nerves to the iliococcygeus and pubococcygeus muscles reduced urethral reflex responses by an additional 25%. Transecting the hypogastric nerves and visceral branches of the pelvic nerves did not affect the urethral reflexes indicating that sneeze-evoked urethral reflexes in normal rats were not mediated by these autonomic pathways. However, hypogastric nerve transection in conscious, chronically spinal cord-injured, female rats reduced urethral baseline pressure, reduced postvoid residual urine volumes, reduced maximal voiding pressure, and increased voiding efficiency. This indicates that sympathetic pathways to the bladder neck and proximal urethra contribute to urethral pressure and functional outlet obstruction and voiding dysfunction after spinal cord injury in unanesthetized animals, but not during sneezing (195).

Neurochemical Anatomy of Rhabdosphincter Motor Neurons

In addition to their unique morphology, neurophysiology, and supraspinal inputs, rhabdosphincter motor neurons in Onuf's nucleus also exhibit a plethora of unique and highly diverse neurotransmitters, receptors, ion channels, and growth factors (Fig. 15, Table 1). While many of the markers listed in Table 1 are likely involved in rhabdosphincter control, it is dangerous to assume a role in rhabdosphincter control based strictly on anatomical association with Onuf's nucleus, since some motor neurons in Onuf's nucleus innervate the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles and thus may be involved in control of sexual function. The following section describes which transmitter and receptor systems have been demonstrated to play a role in control of rhabdosphincter function.

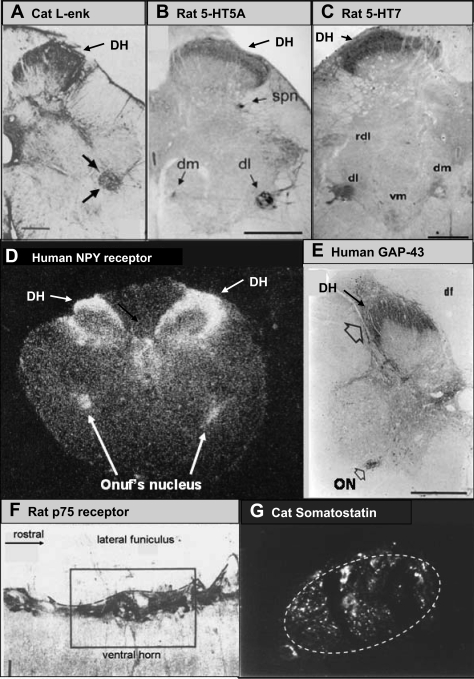

Fig. 15.

Examples of the unique and remarkable association of various neurotransmitters and receptors with pudendal motor neurons in various species. A: cat Leu-enkephalin (Leu-enk) immunoreactivity in an S1 transverse section. Bold arrows point to Onuf's nucleus. DH, dorsal horn. [Adapted from Glazer and Basbaum (55).] B and C: rat 5-HT5A and 5-HT7 receptor immunoreactivity in transverse L6 section. spn, Sacral parasympathetic nucleus; dm, dorsomedial nucleus of the pudendal nerve; dl, dorsolateral of the pudendal nerve; rdl, retrodorsolateral nucleus; vm, ventromedial nucleus. [Adapted from Doly et al. (40) and Doly et al. (41), respectively.] D: neuropeptide Y ([125I]-NPY) autoradiograph of transverse S3 section of human spinal cord. [Adapted from Mantyh et al. (107).] E: growth-associated protein-43 (GAP-43) immunoreactivity in S1 transverse section of human spinal cord. ON, Onuf's nucleus. Open arrow, GAP-43 staining in the dorsal horn. [Adapted from Brook et al. (17).] F: p75 immunoreactivity in a longitudinal L6 section from rat spinal cord through the dorsolateral nucleus of the pudendal nerve. The orientation is similar to that in Fig. 8B except that rostral is toward the right in this panel while 8B1 has rostral to the top. [Adapted from Koliatsos et al. (86).] G: high-power photomicrograph of somatostatin immunoreactivity in Onuf's nucleus (marked by dashed circle) in a transverse S1 section of cat spinal cord. Note that immunoreactivity is restricted to the confines of Onuf's nucleus (K. B. Thor, M. Kawatani, W. C. de Groat, unpublished observation).

Table 1.

Neuronal markers preferentially associated with rhabdosphincter motor neurons in Onuf's nucleus

| Marker | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Transmitters | Enkephalin | (54, 55, 87, 164) |

| CGRP | (7, 54) | |

| Somatostatin | (54, 149) | |

| Norepinephrine | (83, 140) | |

| Serotonin | (84, 85, 140, 164) | |

| Dopamine | (68) | |

| Substance P | (164) | |

| nNOS | (62, 139) | |

| CRF | (77) | |

| CPON | (54) | |

| Receptors | 5-HT1A | (173) |

| 5-HT2A | (194) | |

| 5-HT2C | (29, 64) | |

| 5-HT5A | (40, 194) | |

| 5-HT7 | (41) | |

| Dopamine D2 receptor | (180) | |

| NPY2 | (107) | |

| NK1 | (24) | |

| TRPV-2 | (97) | |

| Ion channel | CaV1.3 | (204) |

| Growth related | p75 (growth factor receptor) | (86) |

| CNTF receptor-α | (104) | |

| GAP-43 | (17, 120) | |

| trkC | (2) |

CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; CRF, corticotrophin-releasing factor; CPON, C-flanking peptide of neuropeptide Y; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; NPY, neuropeptide Y; NK, neurokinin; TRPV-2, transient receptor potential; CaV1−3, voltage-sensitive Ca2+; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; GAP-43, growth-associated peptide; trkC, receptor tyrosine kinase C.

Pharmacology of Urethral and Anal Rhabdosphincters

The excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter, glutamate, mediates initiation of action potentials in rhabdosphincter motor neurons (and subsequent rapid contraction of the muscle) by binding to N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors (51, 196–203). Both spinal reflex activation and supraspinal activation of the rhabdosphincter are sensitive to NMDA and AMPA receptor antagonists (21, 23, 51, 197, 198, 201, 203). Thus, it is useful to think of these transmitters as part of the hardwired reflex circuitry that is involved in all, or none, activation of consistent and reliable storage reflexes, compared with monoamines and peptide transmitters (see below), that play a role as modulators of the reflexes, increasing or decreasing the gain of the reflexes transmitted by the excitatory amino acids (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of experiments demonstrating excitatory and inhibitory effects of pharmacological agents on urethral rhabdosphincter activity

| Excitatory Receptors | References | Inhibitory Receptors | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A* | (21, 22, 39, 60, 61, 169) | κ2-Opioid | (167) |

| 5-HT2 | (35, 110) | α2 Adrenergic | (33, 43, 44) |

| α1-Adrenergic† | (20, 33, 52) | GABA-A | (119) |

| TRH† | (65, 80, 126) | GABA-B | (98, 124, 163, 165) |

| Vasopressin† | (126) | Glycine | (155) |

| NMDA | (23, 99, 101, 102, 203) | ||

| AMPA | (23, 197, 198, 201) |

Indirect effects mediated by supraspinal centers in cats and by suprasegmental (i.e., L3-4) spinal centers in rats.

Direct effects on rhabdosphincter motor neuron demonstrated with in vitro techniques. TRH, thyrotropin-releasing hormone; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartic acid; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid.

The inhibitory amino acids glycine, acting through strychnine-sensitive ionotropic receptors (155, 156), and GABA, acting through both GABA-A (ionotropic) and GABA-B (metabotropic) receptors (8, 9, 119, 165), are thought to be major inhibitory transmitters regulating rhabdosphincter activity. Clinical studies indicate that systemic (98) or intrathecal (124, 163) administration of the GABA-B agonist, baclofen, may reduce bladder-sphincter dyssynergia in some patients with neurogenic bladder. However, because of the ubiquity of glycine and GABA in mediating inhibition of multiple systems, pharmacological studies linking either of these transmitters (or any other inhibitory transmitter for that matter) to the inhibition of rhabdosphincter activity during voiding are not definitive.

In addition to amino acid transmitters, the monoamine transmitters [norepinephrine and serotonin (5-HT)] are also important in modulating rhabdosphincter motor neuron activity (166). It was the preferential distribution of norepinephrine and 5-HT terminals in Onuf's nucleus (83–85, 140) that led to extensive animal studies of noradrenergic and serotonergic control of rhabdosphincter function and eventual clinical studies of duloxetine (Fig. 16), a norepinephrine and 5-HT reuptake inhibitor, as a treatment for stress urinary incontinence (38, 114, 117, 118, 125, 168, 181). Elegant studies in humans using magnetic stimulation of brain and sacral nerve roots (14) have indicated that duloxetine increases the excitability of rhabdosphincter motor neurons to both supraspinal and segmental inputs to increase urethral pressures. Importantly, duloxetine's ability to increase urethral rhabdosphincter activity did not interfere with the inhibition of sphincter activity during voiding (i.e., bladder-sphincter synergy was well maintained) (Fig. 16) (168). Similar clinical results occurred after administration of S,S-reboxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (81, 205). This approach of increasing synaptic levels of 5-HT and/or norepinephrine is logical, since it has been shown that noradrenergic and serotonergic terminals associated with rhabdosphincter motor neurons show an age-dependent decrease in density in rats (144) that might explain the increased incidence of stress incontinence with aging.

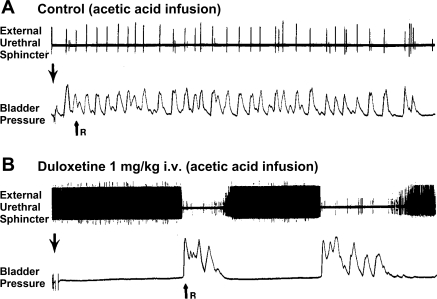

Fig. 16.

Duloxetine (serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) enhances spontaneous sphincter EMG activity and inhibits bladder activity in a chloralose-anesthetized cat. A and B: top tracings are external urethral sphincter (i.e., urethral rhabdosphincter) EMG activity and bottom tracings are bladder pressure recorded during continuous infusion (0.5 ml/min) of 0.5% acetic acid into the bladder. Large downward arrow, infusion begins; small upward arrow (R), release of fluid from urethra. The length of filling from beginning of infusion to release of fluid indicates the bladder capacity. A: control recordings during infusion of dilute acetic acid into the bladder. Note extremely small bladder capacity and very brief bursts of EMG activity after each bladder contraction. B: after administration of 1 mg/kg duloxetine iv, bladder activity is inhibited and bladder capacity increases, while the frequency of sphincter EMG activity is enhanced to the point that individual action potentials are not detectable and appear as a continuous black bar between bladder contractions, while during bladder contractions the EMG activity is virtually abolished. [Adapted from Thor and Katofiasc (168).]

Multiple adrenergic receptor subtypes play a role in control of rhabdosphincter motor neurons, and the results with norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors indicate that these receptors can be activated by endogenous norepinephrine in anesthetized cats (33). Strong evidence exists that α1-adrenoceptors excite rhabdosphincter motor neurons (33, 34, 52). Patch clamp studies (20) have shown a direct depolarizing effect of norepinephrine on rhabdosphincter motor neurons that can be blocked by the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin. Similar conclusions regarding the excitatory effects of α1-adrenoceptors on rhabdosphincter neurons have been reached in clinical studies (52) where decreases in rhabdosphincter activity were seen after administration of prazosin to human subjects. On the other hand, strong evidence exists that α2-adrenoceptor stimulation has the opposite effect, i.e., inhibition, of rhabdosphincter activity (33, 44). Importantly, reflex activity in the sympathetic pathway to the urethral and anal smooth muscle (i.e., the hypogastric nerve) shows similar adrenergic pharmacology–an enhancement of activity by α1-adrenoceptors (33, 34, 141) and inhibition of activity by α2-adrenoceptors (33, 34, 51, 89).

Multiple subtypes of 5-HT receptors are also involved in modulating rhabdosphincter motor neuron excitability. Strong evidence exists that 5-HT2 receptors can excite sphincter motor neurons (35). Indeed duloxetine's facilitatory effects on rhabdosphincter activity in anesthetized cats are mediated in part through activation of 5-HT2 receptors (168). Both 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor agonists increase rhabdosphincter EMG activity in dogs, guinea pigs, and rats (29, 110). Recent in vitro rat spinal cord slice patch-clamp studies show that part of this effect may be directly on rhabdosphincter motor neurons, as opposed to interneurons (20), since 5-HT induces a direct depolarization of rhabdosphincter motor neurons. The effect of 5-HT to enhance the bistable behavior, plateau potentials, and persistent firing of motor neurons (69) very likely contributes to its facilitatory effect on sphincter reflexes and sphincter motor neuron firing (132). Interestingly, substance P, a peptide transmitter that is colocalized with 5-HT in raphéspinal nerve terminals, also produces direct depolarization of rhabdosphincter motor neurons in rat spinal cord slices (126), and thyrotropin-releasing hormone, another peptide transmitter colocalized with 5-HT in nerve terminals, induces excitation of rat sphincter activity (65, 80) in vivo.

A peculiar finding regarding 5-HT2 receptor-induced facilitation of pelvic nerve-evoked rhabdosphincter reflexes in chloralose-anesthetized cats is that the effect is highly reproducible when the spinal cord is isolated (i.e., acute T11 transection) but is highly variable and statistically insignificant when the spinal cord is intact (35). This suggests that supraspinal 5-HT2 receptors have an opposing, inhibitory effect that counteracts their spinal, excitatory effect. Whether this phenomenon is an artifact of anesthesia and/or is specific to cats is important to determine.

Immunohistochemical and molecular studies in humans and dogs (29) have shown that 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptor subtypes are associated with Onuf's nucleus motor neurons. In addition, 5-HT2C receptor mRNA has been localized to anal sphincter motor neurons in the rat (64). On the other hand, another immunohistochemistry study with retrograde labeling of urethral rhabdosphincter motor neurons and ischiocavernosus motor neurons in male rats indicates that the 5-HT5A receptor is associated with the rhabdosphincter, while the 5-HT2A receptor is preferentially associated with the ischiocavernosus (194) and thus may be preferentially involved in sexual function.

As described in the previous section, Inhibition of Urethral Rhabdosphincter Reflexes During Voiding, supraspinal 5-HT1A receptor stimulation also enhances rhabdosphincter activity in cats (Fig. 13) (60, 61, 75, 169, 170). Importantly, the excitatory effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists on the rhabdosphincter can still be overridden by inhibitory mechanisms during voiding, i.e., bladder-sphincter synergy remains despite 8-hydroxy-2(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (8-OH-DPAT)-induced enhancement of rhabdosphincter activity (39, 61, 169, 170) similar to preservation of bladder-sphincter synergy after duloxetine-induced increases in sphincter activity (Fig. 16B). The enhancement of sphincter activity by 8-OH-DPAT in cats is not seen following acute (75, 170) or chronic (60, 61) spinal cord transection, indicating the 5-HT1A receptors mediating these effects are located supraspinally. Furthermore, since 8-OH-DPAT reliably blocked inhibition of sphincter activity by the SUSRIC, it is likely that it enhances sphincter activity through disinhibition. Thus, 5-HT1A receptor activation may inhibit supraspinal neurons that facilitate SUSRIC-mediated inhibition of sphincter reflexes and thereby facilitate urethral rhabdosphincter activity.

The effect of 5-HT1A receptors on rhabdosphincter activity in rats is even more complicated. First, in contrast to cats and humans, rats do not show an inhibition of rhabdosphincter activity during voiding but instead show a high-frequency bursting (or phasic firing) of rhabdosphincter EMG activity during micturition (90). This bursting is necessary for efficient voiding in rats. When the spinal cord is transected, bursting disappears and rats present with urinary retention. Although the bursting is not seen in anesthetized spinal rats at any time (90), in conscious or lightly anesthetized spinal rats, the rhabdosphincter EMG bursting gradually returns in some animals over a period of 6 wk (27, 96). Interestingly, 5-HT1A receptor stimulation can unmask the bursting rhabdosphincter EMG activity in the anesthetized spinal rat (22, 39). Chang et al. (22) further showed that the center responsible for bursting activity in spinal rats was located between the T11 and L4 spinal segments. In the studies of Gu et al. (61), 5-HT1A receptor stimulation had no influence on the asynchronous rhabdosphincter activity that precedes and follows micturition-associated bursting, it only reorganized the activity into the bursting or phasic characteristics that accompany micturition.

Another aspect of 5-HT1A receptor function in rats can be seen from studies of pelvic nerve-to-rhabdosphincter reflex potentiation. This reflex can be potentiated by prolonged, low-frequency electrical stimulation of the pelvic nerve and by bladder distention (21–23, 100–102). Subsequent studies showed that the potentiation involved a 5-HT1A receptor-based link (21, 25).