Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy is the commonest cause of end-stage renal disease. Inordinate kidney growth and glomerular hyperfiltration at the very early stages of diabetes are putative antecedents to this disease. The kidney is the only organ that grows larger with the onset of diabetes mellitus, yet there remains confusion about the mechanism and significance of this growth. Here we show that kidney proximal tubule cells in culture transition to senescence in response to oxidative stress. We further determine the temporal expression of G1 phase cell cycle components in rat kidney cortex at days 4 and 10 of streptozotocin diabetes to evaluate changes in this growth response. In diabetic rats we observe increases in kidney weight-to-body weight ratios correlating with increases in expression of the growth-related proteins in the kidney at day 4 after induction of diabetes. However, at day 10 we find a decrease in this profile in diabetic animals coincident with increased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor expressions. We observe no change in caspase-3 expression in the diabetic kidneys at these early time points; however, diabetic animals demonstrate reduced kidney connexin 43 and increased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expressions and increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity in cortical tubules. In summary, diabetic kidneys exhibit an early temporal induction of growth phase components followed by their suppression concurrent with the induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and markers of senescence. These data delineate a phenotypic change in cortical tubules early in the pathogenesis of diabetes that may contribute to further downstream complications of the disease.

Keywords: proximal tubule, hypertrophy, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, connexin 43

the functional unit of the kidney, the single nephron, shows a particular organization including a tubuloglomerular contact site that contributes to the fine coordination between glomerular filtration and tubular reabsorption through the mechanism of tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF). The TGF mechanism refers to a series of events whereby changes in the Na+, Cl−, and K+ concentrations in the tubular fluid are sensed by the macula densa cells at this contact site. An increase or decrease in late proximal tubular flow rate, and thus in Na+, Cl−, and K+ delivery at the macula densa, elicits inverse changes in glomerular filtration rate (44). There is now convincing evidence for a primary increase of fluid and electrolyte reabsorption in the proximal tubule in rats with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced experimental type 1 diabetes (6, 35, 43, 45, 47) as well as in early type 1 diabetes in humans (9, 23). Increased reabsorption lowers the concentration of Na+, Cl−, and K+ in the tubular fluid at the macula densa thereby eliciting a TGF-dependent increase in nephron filtration rate (47, 48). Inhibiting the synthesis of polyamines required for growth results in a parallel decrease in proximal tubular hyperreabsorption and glomerular filtration in diabetic rats (43). This illustrates the impact of tubular growth on kidney function in response to STZ-diabetes. Glomerular expansion would also be affected by suppression of kidney growth.

With regard to total volume, growth of the diabetic kidney is attributed primarily to the proximal tubule, where a period of hyperplasia precedes diabetic hypertrophy (25). High glucose treatment of a mesangial cell line stimulates a biphasic early cell proliferation (24 to 48 h) and a later growth inhibitory phase (72 to 96 h) (58). The early proliferative phase is associated with increased expression of the immediate early genes and growth factors (61). The diabetic kidney begins changing from hyperplastic to hypertrophic growth very early in the course of hyperglycemia, at approximately day 4 in the STZ model (25), which matches the time frame of hyperplasia we observed using 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (15). Expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CKI) p27KIP1 (p27) increases in response to hyperglycemia or diabetes, which can be attributed, in part, to induction by PKC (57) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (26). Targeted disruption of the p27 gene does not affect hyperglycemia in the STZ diabetic model but does decrease hypertrophy, with resultant reductions in albuminuria, extracellular matrix (ECM) production, glomerulosclerosis, and structural damage (5, 55). TGF-β is thought to contribute to ECM production in this model, so it is curious as p27 is downstream from TGF-β that diabetic p27−/− mice display markedly lower ECM production even though TGF-β levels remain unaltered (5, 55). These data demonstrate a key role of p27 in diabetic hypertrophy, which is an important component of disease progression. This raises the question, is there something unusual about cellular hypertrophy in diabetes?

We hypothesize that diabetic hypertrophy is a phenotypic transition to senescence. Senescence is a tumor suppressor mechanism to halt cells from replicating and passing on a potentially damaged genome. Like early diabetic hypertrophy, senescent arrest requires upregulation of CKI (2, 24, 33). Although the prototypical senescent arrest involves the temporal induction of p21WAF1,CIP1 (p21) and p16INK4a (p16) (39, 42), studies demonstrate that induction of p27 can impose a senescent-like growth arrest (3, 22, 60). Oxidative stress produced by exposure of human diploid fibroblasts to hydrogen peroxide induces senescence and was attributed to TGF-β induction (19). Furthermore, the active braking of the cell cycle by CKI mediates a G1 cell cycle arrest in both diabetic hypertrophy and senescence resulting in cells that are unresponsive to mitogenic stimulation. Here we show evidence that in the early STZ diabetic kidney there is an early phenotypic change, primarily in cortical tubule cells. Senescent cells exhibit several aspects of a fairly well-differentiated phenotype; however, this phenotype is skewed in several parameters from that of the normal parental cell type (11). Furthermore, senescent cells would contribute to the oxidative stress, production of growth factors, and ECM observed in diabetes and would be resistant to apoptotic remodeling (4, 40). As such, the transition of proximal tubule cells to a senescent phenotype would offer a mechanism whereby diabetic hypertrophy contributes to disease progression.

It may be that several peculiar aspects of kidney function in early diabetes are not consequences of kidney growth, per se, but are consequences of the mechanism whereby the kidney has grown. Proximal tubular cells that exhibit a senescent arrest may present a chronically altered phenotype that affects transport function, explain unusual phenomena like the salt paradox of the early diabetic kidney (46), and contribute to later diabetic complications (7, 36, 37).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise stated. Opossum kidney proximal tubule cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media-Ham's F-12 mix (DMEM/F-12; Cellgro, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 5% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA), 2 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air-5% CO2. The media contained sodium pyruvate (110 mg/l) which could dampen the effects of the H2O2. Control cells at 3 days were plated at 1.5 × 105 cells per well of a 6-well plate, and both 150 μM and 300 μM concentrations of H2O2-treated cells were plated at 3 × 105 cells per well. Cells at 6 days were plated at various densities to compensate for growth starting at 0.5 × 104 for control and 1.5 × 105 for H2O2.

Animals and STZ

Physiologic parameters.

Male adult Sprague-Dawley rats (purchased from Harlan Teklad) were housed and handled in accordance with Veterans Administration and National Institutes of Health guidelines under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols. Rats were made diabetic by STZ (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO; 65 mg/kg ip) dissolved in sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.2). One day later, the glucose concentration was determined in tail blood samples, and only those animals with blood glucose levels >300 mg/dl were included in further experiments. Vehicle-injected nondiabetic rats served as controls. Blood glucose levels were determined at least four times in every rat after STZ injection, and mean values were calculated. Kidneys were harvested under terminal inactin anesthesia at 4 or 10 days after STZ application. On all left kidneys, kidney dry weight was determined, whereas right kidneys were harvested for Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis.

Kidneys were harvested and homogenized in lysis buffer [lysis buffer: 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 4 mM NaF, Complete protease cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany), and 1 mM NaVO4 in PBS]. Lysates at 50 μg/lane were resolved on NuPAGE gels in MOPS buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Gel proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoblotted with the appropriate primary antibody, as indicated. The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for autoradiographic detection by ECL Plus (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), with densitometric analysis by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Activity

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) enzymatic assays were performed as per Dimri et al. (16), modified to be run at pH 6.3 rather than 6.0 because as we find lower background in our samples. A similar shift in pH to minimize background interference from β-galactosidase present in all cells was previously reported (28). In brief, kidneys were harvested, frozen in OCT compound, and sectioned at 10 μM. Sections were fixed in 0.5% gluteraldehyde for 5 min, washed and placed in X-gal solution (1 mg/ml X-gal, 5 mM K3Fe[CN]6, 5 mM K4Fe[CN]6, 2 mM MgCl2, and 150 mM NaCl, in 40 mM citric acid, phosphate at pH 6.3) overnight at 37°C. Diabetic animals in this group were treated with STZ as above, but for 14 days.

Statistical Evaluation

Variations between samples within groups were analyzed by ANOVA, with significance determined by Fisher's protected least-significant difference post-hoc test. KaleidaGraph software (version 4.04, Synergy Software) was used for these analyses.

RESULTS

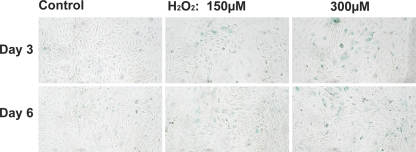

SA-β-Gal Response of Kidney Proximal Tubule Cells to Oxidative Stress

We first determined whether proximal tubule cells transition to a senescent phenotype upon exposure to oxidative stress. Opossum kidney proximal tubule cells were exposed to 150 μM or 300 μM H2O2 for 3 h and then left to incubate at 37°C in fresh media for 3 or 6 days. Figure 1 demonstrates a time and dose response to H2O2 as demonstrated by increased SA-β-Gal activity. Time after exposure to H2O2 is required as late-stage senescence takes time to evolve. This 3- to 6-day incubation period, it should be remembered, allows the nonaffected cells to continue growing, whereas the senescent arrested cells do not. Furthermore, twice as many cells were seeded for the H2O2 group to reach equal confluence with the nontreated controls. We assume from this delay that some cells exposed to H2O2 repaired and reentered growth phase while others progressed to senescent arrest. Nonetheless, we do see some minor staining in the control cells, yet few, if any, cells are observed with a senescent morphology, i.e., larger (G1 arrested) cells with a “sunny side up egg” appearance. This aberrant morphology and SA-β-Gal staining are clearly more evident in the H2O2-treated cells (Fig. 1). We did not formulate DMEM/F-12 without pyruvate for these experiments so the cells may be more sensitive to oxidative stress than observed here.

Fig. 1.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity in opossum kidney (OK) cells exposed to H2O2. OK cells in 6-well plates were exposed to 150 or 300 μM H2O2 for 3 h, washed, and incubated in DMEM/F-12 + 5% FBS at 37°C for 3 or 6 days. SA-β-Gal activity was determined as per Dimri et al. (16), except that the X-gal solution was at pH 6.3 instead of pH 6.0. Representative photograph of 3 wells per condition.

Physiology of STZ-Treated Rats

STZ increased blood glucose levels compared with control rats (439 ± 19 vs. 112 ± 3 mg/dl); the levels were similar at 4 or 10 days after STZ. STZ increased absolute as well as relative kidney weight at 4 or 10 days after STZ (Table 1). These measurements imply that kidney growth occurs largely by day 4.

Table 1.

Body and kidney weights

| Control |

STZ Diabetes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 Days | 10 Days | 4 Days | 10 Days | |

| IB, g | 214 ± 4 | 227 ± 2 | 213 ± 3 | 214 ± 7 |

| FB, g | 260 ± 3 | 318 ± 9 | 228 ± 9 | 260 ± 8 |

| KW, mg | 265 ± 6 | 278 ± 2 | 297 ± 11 | 307 ± 12 |

| KW/IB, mg/g | 1.25 ± 0.03 | 1.22 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.04 | 1.44 ± 0.05 |

| KW/FB, mg/g | 1.02 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.02 | 1.31 ± 0.07 | 1.18 ± 0.04 |

Values are means ± SE. STZ, streptozotocin; IB, initial body weight; FB, final body weight; KW, kidney weight.

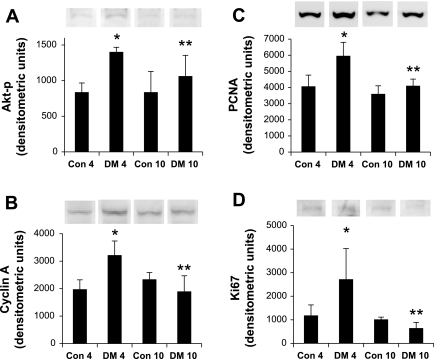

Temporal Effects of Diabetes on the Growth Response

Physiology measurements display diabetic kidney growth by the increased kidney weight-to-body weight ratio, as shown in Table 1. Here we evaluated expression of four proteins that are associated with growth and evaluate their changes in expression with diabetes over two time points. The first, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt, comprises a coordinated network of pathways supporting antiapoptotic yet progrowth and angiogenic responses that is upregulated by a variety of growth factors in the early stages of kidney growth in diabetes. Activation of Akt requires phosphorylation. The antibody used in these studies detects Thr308-phosphorylated Akt, and thus activated form, of the enzyme (Akt-p; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The second is cyclin A; its levels increase late in G1 in response to transactivation of E2F. Cyclin A binds with cyclin-dependent kinase-2 (cdk2) to form an active complex necessary for G1 to S phase transition (21) and S phase transit (20). The third, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), belongs to the DNA family of sliding clamps that encircles DNA and tethers polymerases firmly to it during DNA synthesis. The fourth, Ki67, represents another common marker of cellular proliferation. In accord with the measured kidney growth we observe an upregulation of these growth-associated proteins at day 4. At day 10 these differences are no longer significant. Akt-p, cyclin A, PCNA, and Ki67 expressions at 4 and 10 days are shown in Fig. 2, A–D, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Temporal effects of diabetes on the expression of growth mediators in kidney. Shown are changes in protein expression of phosphorylated Akt (Akt-p; A), cyclin A (B), PCNA (C), and Ki67 (D) by immunoblotting. Akt-p, cyclin A, PCNA, and Ki67 expressions are all significantly elevated after the administration of streptozotocin (STZ) at day 4 (DM4*) relative to control at day 4 (Con4); left two columns. These changes in the diabetic animals do not remain significantly different from untreated controls at day 10; right two columns (Con10 vs. DM10). Furthermore, the growth response marker increases in diabetic animals at day 4 are significantly attenuated by day 10 (DM10**). The y-axes are relative densitometric units as determined by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and normalized for loading against β-actin. Western blot images are representative samples from the same autoradiograph. Con, vehicle-treated animals; DM, STZ-treated animals. Numbers represent time in days after treatment. Results represent means ± SE; n = 4. *Con4 vs. DM4; **DM4 vs. DM10: Akt-p, *P = 0.0033, **P = 0.0485; cyclin A, *P = 0.0018, **P = 0.0011; PCNA, *P = 0.0012, **P = 0.0014; Ki67, *P = 0.0063, **P = 0.0018.

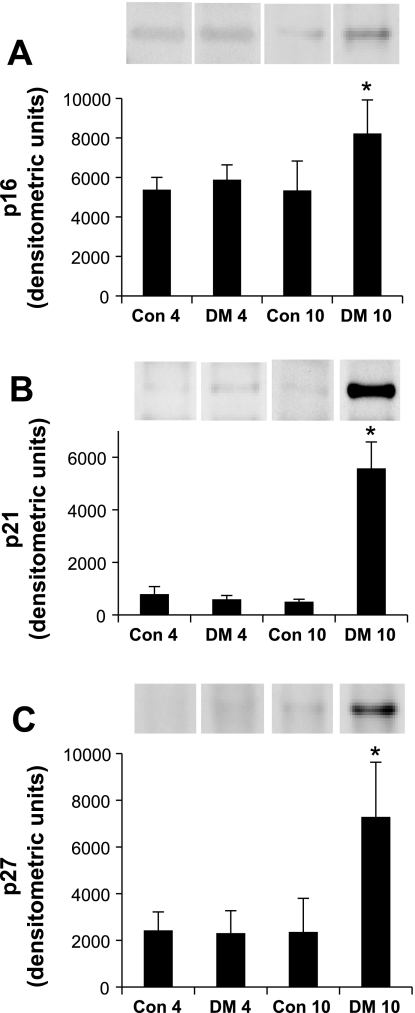

Temporal Effects of Diabetes on the CKI Profile

Much of what is known about the G1 phase of the cell cycle concerns the phosphorylation and inactivation of the restriction point guardian, the retinoblastoma protein (Rb). Hyperphosphorylation of Rb is carried out in G1 by cyclin D/cdk4/6 and cyclin E/cdk2 (18). Human diploid fibroblasts that reach generational senescence demonstrate a failure to hyperphosphorylate Rb. Senescent cells temporally induce the expression of CKI, particularly p16 (2, 24) and p21 (33). p21 is a universal cyclin/CDK complex inhibitor, whereas p16 binds monomeric cdk4 and cdk6, preventing their association with cyclin D. The switch from hyperplastic to hypertrophic growth of the diabetic kidney is attributed to induction of p27 via TGF-β (25, 26, 30, 56). Increased p27 expression has been associated with senescence (8). Although there is little expression of these CKIs in response to diabetes at day 4, where the growth phase is prevalent, there is a marked response by day 10 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the negative regulation of Forkhead box, class O (FOXO) on cell cycle progression and proliferation is dependent on p27, which it transcriptionally activates (32). Active Akt phosphorylates and inactivates both FOXO and p27, translocating them out of the nucleus (27). Here we show a temporal decrease in Akt-p (Fig. 2A) that corresponds with an increase in p27 expression (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Temporal expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CKI) in kidney in response to diabetes. Shown are changes in protein expression of p16INK4a (A), p21WAF1,CIP1 (B), and p27KIP1 (C) either 4 days (left two columns) or 10 days (right two columns) without or with STZ treatment. All three CKIs are significantly increased at day 10 after STZ (DM10*) but are not significantly different from untreated controls at day 4. Labels at axes as per Fig. 2. Results represent means ± SE; n = 4. *Con10 vs. DM10 and DM4 vs. DM10, respectively: p16, *P = 0.0062, P = 0.0196; p21, *P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001; p27, *P = 0.0006, P = 0.0005.

Cyclin A is associated with S phase entry and G1 to S transition. Its expression is regulated by E2F. In senescence, CKI activation of Rb inhibits E2F and thus suppresses cyclin A levels (17). This would correlate these CKI results with the above results of Fig. 2B.

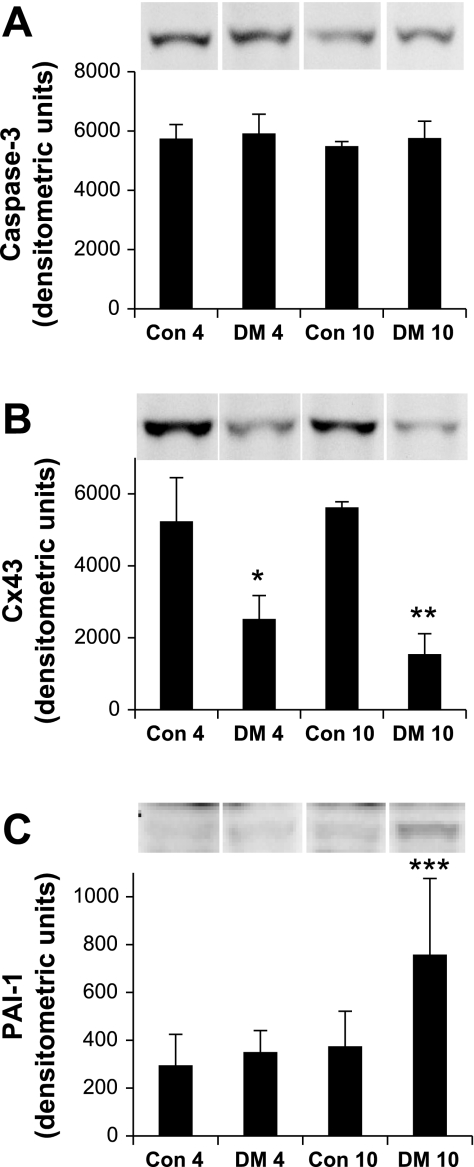

Effects of Diabetes on Apoptotic and Senescent Markers

Both the extrinsic or death receptor pathway and the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway converge at the execution caspase, caspase-3. Cleavage of caspase-3 initiates a series of apoptotic events including protein modification, DNA fragmentation, apoptotic body formation, and externalization of membrane phosphatidylserine for phagocytic recognition. Expression of caspase-3 is observed in all samples, yet there is no significant variation between control and diabetic animals at either 4 or 10 days, implying that we do not observe overt apoptosis at this early-onset stage of diabetes (Fig. 4A). Connexin 43 (Cx43) is a member of a family of hexameric gap proteins important in cell-cell communication, differentiation, and growth control. Reduced expression of Cx43 in aging and its correlation with senescence suggest Cx43 as a senescent biomarker (41). Cx43 tends to decrease in diabetic animals relative to their nondiabetic controls at day 4 and becomes significant by day 10 (Fig. 4B). The remodeling of ECM is a common event in aging. Senescent fibroblasts overexpress plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 (PAI-1), which regulates ECM fibrolytic activity. We observe an increase in PAI-1 in diabetic animals at day 10 (Fig. 4C). Variations in ECM proteins occur late in the development of senescence.

Fig. 4.

Temporal expression of protein markers of cellular stress response mechanisms in the diabetic kidney. A: apoptotic execution caspase-3 expression remains unchanged from controls at both 4 days (left two columns) and 10 days (right two columns) after STZ treatment. B: connexin-43 (Cx43) expression decreases in senescence and significantly decreases in response to STZ treatment at both 4 and 10 days. C: plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 (PAI-1) expression increases in senescence and remains unchanged at day 4 but is significantly increased at day 10 after STZ treatment. Labels at axes as per Fig. 2. Results represent means ± SE, n = 4, except PAI-1 DM4, where n = 3. Cx43, *Con4 vs. DM4, P = 0.0092; **Con10 vs. DM10, P = 0.0005; PAI-1, ***Con10 vs. DM10, P = 0.0196, and DM4 vs. DM10, P = 0.0212.

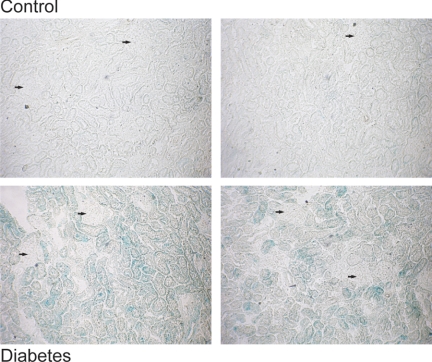

SA-β-Gal activity increases in response to diabetes by this 14-day time point, predominantly in the cortical tubules (Fig. 5). It should be noted that SA-β-Gal activity, although obvious in the diabetic animals, was not evenly distributed throughout the cortex. Some areas were more prominent than others, which would be in accord with the paracrine effects noted of senescent cells (7). Endothelial cells, glomerular components, and medulla do not demonstrate discernable staining at this early time point.

Fig. 5.

SA-β-Gal activity increases in response to diabetes. Activity of the senescent marker SA-β-Gal is noticeably increased in 14-day diabetic animals. The label is observed primarily in cortical tubules and is not observed to any significant extent at this time point in the glomeruli or endothelial cells. Label is also conspicuously decreased in medullary tubules compared with cortical tubules. Arrows pointing to glomeruli in photos are for comparison purposes. Each photograph represents a separate animal.

DISCUSSION

Diabetes mellitus affects the kidney in stages, with sclerosis and kidney failure occurring many years after onset. Here we evaluate the very early stages of disease where the kidney initiates growth, hypertrophy, and hyperfiltration. We find that the molecular signature of senescence develops during this early phase, with SA-β-Gal staining localized principally to the cortical, proximal tubules.

Biopsies from diabetic patients display decreased Cx43 in podocytes (38) and increases in p16 in podocytes and proximal tubule cells (50), with increased SA-β-Gal activity in the tubular component (50). It is unclear from these studies alone whether diabetes induces senescence or whether patients with a higher complement of senescent cells are more susceptible to disease progression. It is also unclear whether senescence is involved in the pathogenesis of the disease, or if it is a late phase downstream effect. Diabetes produces a vascular aging effect, and high glucose (59) or advanced glycosylation end-products induce senescence in endothelial cells. Treatment with the peroxynitrite inhibitor ebselen suppresses this latter effect (10, 12). Other in vitro studies with high glucose demonstrate induction of senescence in kidney mesangial cells (62) and proximal tubule cells (49) in culture.

Conversion of cortical tubules to a senescent-like phenotype could constitute a significant factor in the progression of diabetic kidney complications. Proximal tubules comprise the major faction of diabetic hypertrophic growth. Recent work shows that proliferation of proximal tubules is primarily from dedifferentiated cells, not resident stem cells or hematopoietic stem cells (52, 53). These studies further demonstrate that a large population of proximal tubules resides in a prolonged G1 phase, which would suggest a rapid proliferative capacity in response to an emergency (54). Terminally differentiated cells cannot progress to senescence (51), but dedifferentiated proximal tubule cells responding to mitogenic factors would lend themselves to senescent arrest. As stated previously, hypertrophic kidney growth alone may not set in motion the spiraling complications leading to end-stage renal disease. Overexpression of fibronectin and PAI-1 is observed in senescence and diabetes. Thus, the senescent phenotype may contribute to diabetic fibrosis. Senescent cells display a reduction in proteasomal mediated protein degradation (14, 40), which would be a factor for the increased hypertrophy due to decreased proteolysis and progression in later stage diabetes. Patients with overt type 2 diabetic nephropathy display a decrease in Cx43 expression, as observed in senescence (41), on podocytes relative to patients with minor glomerular abnormalities (38). These changes directly correlated with a decline in renal function. In addition, senescence leads to increased TGF-β expression (19), protein oxidation (14, 40), and cellular oxidant production of both superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide (4). Suppression of autophagy leads to increased oxidative stress with damage to membranes, proteins and DNA, and genomic instability (31), further promoting senescence. Senescent cells perpetuate inflammatory cytokine feedback loops that promote autocrine and paracrine effects (1, 29). These factors all support an inflammatory milieu and increased oxidative stress. The contribution of oxidative stress to complications in diabetes is a complex and controversial issue. Evidence supports a compelling role of glucose-mediated metabolic imbalances in the production of free radicals and the progression of diabetic complications (34). All the factors associated with senescent cells are apparent in the progression of diabetic complications. This hypothesis is in accord with data from p27 knockout mice that exhibit markedly reduced glucose-mediated hypertrophy (5, 55). Importantly, although blood glucose levels were comparable in diabetic p27+/+ and p27−/− animals, parameters of downstream complications of diabetes including albuminuria, structural damage, and ECM production were all markedly attenuated in the p27−/− animals.

Overall, a single cell blocked from passing on a damaged genome will not affect the organism, yet an accumulation of senescent cells may contribute to the disruption of local tissue integrity and potentiate future declines in function. With aging comes a natural increase in senescent cells and decreases in autophagy. These cells would complement the stress that the diabetes-induced premature senescent cells generate, and along with further decreases in autophagy we hypothesize would place older individuals at a higher risk of developing diabetic nephropathy. However, although the overall senescent load increases with age, it can vary greatly even within the same age group, as observed in rat kidneys (13). A question then is, can the heterogeneity of senescence explain or correlate with the heterogeneity observed in the progression of diabetes? Futher advances in the field of senescence will help us to better address this question.

Determining that proximal tubule cells convert to a senescent phenotype very early in response to diabetes is an important first step toward defining the components that comprise and underlie the pathogenesis of the disease. Targeting these senescent-like cells has the potential to relieve or possibly resolve tubular dysfunction, glomerular hyperfiltration, and oxidative stress and attenuate downstream diabetic complications associated with disease progression.

GRANTS

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK070123, DK070667, DK02920, DK56248, DK28602, and University of Alabama at Birmingham-University of California San Diego O'Brien Center for Acute Kidney Injury Research Grant P30DK079337, and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta JC, O′Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, Fumagalli M, Da Costa M, Brown C, Popov N, Takatsu Y, Melamed J, d'Adda di Fagagna F, Bernard D, Hernando E, Gil J. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell 133: 1006–1018, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcorta DA, Xiong Y, Phelps D, Hannon G, Beach D, Barrett JC. Involvement of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 (INK4a) in replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 13742–13747, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander K, Hinds PW. Requirement for p27(KIP1) in retinoblastoma protein-mediated senescence. Mol Cell Biol 21: 3616–3631, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen RG, Tresini M, Keogh BP, Doggett DL, Cristofalo VJ. Differences in electron transport potential, antioxidant defenses, and oxidant generation in young and senescent fetal lung fibroblasts (WI-38). J Cell Physiol 180: 114–122, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awazu M, Omori S, Ishikura K, Hida M, Fujita H. The lack of cyclin kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1) ameliorates progression of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 699–708, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bank N, Aynedjian HS. Progressive increases in luminal glucose stimulate proximal sodium absorption in normal and diabetic rats. J Clin Invest 86: 309–316, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartek J, Hodny Z, Lukas J. Cytokine loops driving senescence. Nat Cell Biol 10: 887–889, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bringold F, Serrano M. Tumor suppressors and oncogenes in cellular senescence. Exp Gerontol 35: 317–329, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brochner-Mortensen J, Stockel M, Sorensen PJ, Nielsen AH, Ditzel J. Proximal glomerulo-tubular balance in patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 27: 189–192, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodsky SV, Gealekman O, Chen J, Zhang F, Togashi N, Crabtree M, Gross SS, Nasjletti A, Goligorsky MS. Prevention and reversal of premature endothelial cell senescence and vasculopathy in obesity-induced diabetes by ebselen. Circ Res 94: 377–384, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campisi J. Cellular senescence as a tumor-suppressor mechanism. Trends Cell Biol 11: S27–S31, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Park HC, Patschan S, Brodsky SV, Gealikman O, Kuo MC, Li H, Addabbo F, Zhang F, Nasjletti A, Gross SS, Goligorsky MS. Premature vascular senescence in metabolic syndrome: could it be prevented and reversed by a selenorganic antioxidant and peroxynitrite scavenger ebselen? Drug Discov Today Ther Strateg 4: 93–99, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chkhotua A, Shohat M, Tobar A, Magal N, Kaganovski E, Shapira Z, Yussim A. Replicative senescence in organ transplantation-mechanisms and significance. Transpl Immunol 9: 165–171, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chondrogianni N, Stratford FL, Trougakos IP, Friguet B, Rivett AJ, Gonos ES. Central role of the proteasome in senescence and survival of human fibroblasts: induction of a senescence-like phenotype upon its inhibition and resistance to stress upon its activation. J Biol Chem 278: 28026–28037, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng A, Munger KA, Valdivielso JM, Satriano J, Lortie M, Blantz RC, Thomson SC. Increased expression of ornithine decarboxylase in distal tubules of early diabetic rat kidneys: are polyamines paracrine hypertrophic factors? Diabetes 52: 1235–1239, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, Peacocke M, Campisi J. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 9363–9367, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dulic V, Drullinger LF, Lees E, Reed SI, Stein GH. Altered regulation of G1 cyclins in senescent human diploid fibroblasts: accumulation of inactive cyclin E-Cdk2 and cyclin D1-Cdk2 complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 11034–11038, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ezhevsky SA, Nagahara H, Vocero-Akbani AM, Gius DR, Wei MC, Dowdy SF. Hypo-phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) by cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes results in active pRb. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 10699–10704, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frippiat C, Chen QM, Zdanov S, Magalhaes JP, Remacle J, Toussaint O. Subcytotoxic H2O2 stress triggers a release of transforming growth factor-beta 1, which induces biomarkers of cellular senescence of human diploid fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 276: 2531–2537, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girard F, Strausfeld U, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ. Cyclin A is required for the onset of DNA replication in mammalian fibroblasts. Cell 67: 1169–1179, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guadagno TM, Ohtsubo M, Roberts JM, Assoian RK. A link between cyclin A expression and adhesion-dependent cell cycle progression. Science 262: 1572–1575, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haddad MM, Xu W, Schwahn DJ, Liao F, Medrano EE. Activation of a cAMP pathway and induction of melanogenesis correlate with association of p16(INK4) and p27(KIP1) to CDKs, loss of E2F-binding activity, and premature senescence of human melanocytes. Exp Cell Res 253: 561–572, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannedouche TP, Delgado AG, Gnionsahe DA, Boitard C, Lacour B, Grunfeld JP. Renal hemodynamics and segmental tubular reabsorption in early type 1 diabetes. Kidney Int 37: 1126–1133, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara E, Smith R, Parry D, Tahara H, Stone S, Peters G. Regulation of p16CDKN2 expression and its implications for cell immortalization and senescence. Mol Cell Biol 16: 859–867, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang HC, Preisig PA. G1 kinases and transforming growth factor-beta signaling are associated with a growth pattern switch in diabetes-induced renal growth. Kidney Int 58: 162–172, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamesaki H, Nishizawa K, Michaud GY, Cossman J, Kiyono T. TGF-beta 1 induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 mRNA and protein in murine B cells. J Immunol 160: 770–777, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kau TR, Way JC, Silver PA. Nuclear transport and cancer: from mechanism to intervention. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 106–117, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer DL, Chang BD, Chen Y, Diegelman P, Alm K, Black AR, Roninson IB, Porter CW. Polyamine depletion in human melanoma cells leads to G1 arrest associated with induction of p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1, changes in the expression of p21-regulated genes, and a senescence-like phenotype. Cancer Res 61: 7754–7762, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, Aarden LA, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 133: 1019–1031, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu B, Preisig P. TGF-β1-mediated hypertrophy involves inhibiting pRB phosphorylation by blocking activation of cyclin E kinase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F186–F194, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B, Karp CM, Bray K, Degenhardt K, Chen G, Jin S, White E. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes Dev 21: 1367–1381, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medema RH, Kops GJ, Bos JL, Burgering BM. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature 404: 782–787, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noda A, Ning Y, Venable SF, Pereira-Smith OM, Smith JR. Cloning of senescent cell-derived inhibitors of DNA synthesis using an expression screen. Exp Cell Res 211: 90–98, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nyengaard JR, Ido Y, Kilo C, Williamson JR. Interactions between hyperglycemia and hypoxia: implications for diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 53: 2931–2938, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollock CA, Lawrence JR, Field MJ. Tubular sodium handling and tubuloglomerular feedback in experimental diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F946–F952, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satriano J. Arginine pathways and the inflammatory response: interregulation of nitric oxide and polyamines: review article. Amino Acids 26: 321–329, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Satriano J. Kidney growth, hypertrophy and the unifying mechanism of diabetic complications. Amino Acids 33: 331–339, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawai K, Mukoyama M, Mori K, Yokoi H, Koshikawa M, Yoshioka T, Takeda R, Sugawara A, Kuwahara T, Saleem MA, Ogawa O, Nakao K. Redistribution of connexin43 expression in glomerular podocytes predicts poor renal prognosis in patients with type 2 diabetes and overt nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 2472–2477, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 88: 593–602, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sitte N, Merker K, von Zglinicki T, Grune T. Protein oxidation and degradation during proliferative senescence of human MRC-5 fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med 28: 701–708, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Statuto M, Bianchi C, Perego R, Del Monte U. Drop of connexin 43 in replicative senescence of human fibroblasts HEL-299 as a possible biomarker of senescence. Exp Gerontol 37: 1113–1120, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stein GH, Drullinger LF, Soulard A, Dulic V. Differential roles for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p16 in the mechanisms of senescence and differentiation in human fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol 19: 2109–2117, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomson SC, Deng A, Bao D, Satriano J, Blantz RC, Vallon V. Ornithine decarboxylase, kidney size, and the tubular hypothesis of glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes. J Clin Invest 107: 217–224, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vallon V. Tubuloglomerular feedback and the control of glomerular filtration rate. News Physiol Sci 18: 169–174, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallon V, Blantz RC, Thomson S. Glomerular hyperfiltration and the salt paradox in early type 1 diabetes mellitus: a tubulo-centric view. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 530–537, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vallon V, Huang DY, Deng A, Richter K, Blantz RC, Thomson S. Salt-sensitivity of proximal reabsorption alters macula densa salt and explains the paradoxical effect of dietary salt on glomerular filtration rate in diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1865–1871, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vallon V, Richter K, Blantz RC, Thomson S, Osswald H. Glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes mellitus: potential role of tubular reabsorption. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2569–2576, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vallon V, Schroth J, Satriano J, Blantz RC, Thomson SC, Rieg T. Adenosine A(1) receptors determine glomerular hyperfiltration and the salt paradox in early streptozotocin diabetes mellitus. Nephron Physiol 111: p30–38, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verzola D, Bertolotto MB, Villaggio B, Ottonello L, Dallegri F, Frumento G, Berruti V, Gandolfo MT, Garibotto G, Deferran G. Taurine prevents apoptosis induced by high ambient glucose in human tubule renal cells. J Investig Med 50: 443–451, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verzola D, Gandolfo MT, Gaetani G, Ferraris A, Mangerini R, Ferrario F, Villaggio B, Gianiorio F, Tosetti F, Weiss U, Traverso P, Mji M, Deferrari G, Garibotto G. Accelerated senescence in the kidneys of patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1563–F1573, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vicencio JM, Galluzzi L, Tajeddine N, Ortiz C, Criollo A, Tasdemir E, Morselli E, Ben Younes A, Maiuri MC, Lavandero S, Kroemer G. Senescence, apoptosis or autophagy? When a damaged cell must decide its path–a mini-review. Gerontology 54: 92–99, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogetseder A, Palan T, Bacic D, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Proximal tubular epithelial cells are generated by division of differentiated cells in the healthy kidney. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C807–C813, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogetseder A, Picard N, Gaspert A, Walch M, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Proliferation capacity of the renal proximal tubule involves the bulk of differentiated epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C22–C28, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Witzgall R. Are renal proximal tubular epithelial cells constantly prepared for an emergency? Focus on “The proliferation capacity of the renal proximal tubule involves the bulk of differentiated epithelial cells”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C1–C3, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolf G, Schanze A, Stahl RA, Shankland SJ, Amann K. p27(Kip1) Knockout mice are protected from diabetic nephropathy: evidence for p27(Kip1) haplotype insufficiency. Kidney Int 68: 1583–1589, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolf G, Schroeder R, Zahner G, Stahl RA, Shankland SJ. High glucose-induced hypertrophy of mesangial cells requires p27(Kip1), an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. Am J Pathol 158: 1091–1100, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolf G, Schroeder R, Ziyadeh FN, Thaiss F, Zahner G, Stahl RA. High glucose stimulates expression of p27Kip1 in cultured mouse mesangial cells: relationship to hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F348–F356, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolf G, Sharma K, Chen Y, Ericksen M, Ziyadeh FN. High glucose-induced proliferation in mesangial cells is reversed by autocrine TGF-beta. Kidney Int 42: 647–656, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokoi T, Fukuo K, Yasuda O, Hotta M, Miyazaki J, Takemura Y, Kawamoto H, Ichijo H, Ogihara T. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 mediates cellular senescence induced by high glucose in endothelial cells. Diabetes 55: 1660–1665, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoon G, Kim HJ, Yoon YS, Cho H, Lim IK, Lee JH. Iron chelation-induced senescence-like growth arrest in hepatocyte cell lines: association of transforming growth factor beta1 (TGF-beta1)-mediated p27Kip1 expression. Biochem J 366: 613–621, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Young BA, Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Eng E, Gordon K, Floege J, Couser WG, Seidel K. Cellular events in the evolution of experimental diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 47: 935–944, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang X, Chen X, Wu D, Liu W, Wang J, Feng Z, Cai G, Fu B, Hong Q, Du J. Downregulation of connexin 43 expression by high glucose induces senescence in glomerular mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1532–1542, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]