Abstract

Hypernatremia exerts multiple cellular effects, many of which could influence the outcome of an ischemic event. To further evaluate these effects of hypernatremia, isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes were chronically incubated with medium containing either normal (142 mM) or elevated sodium (167 mM) and then transferred to medium containing deoxyglucose and the electron transport chain inhibitor amobarbital. Chronic hypernatremia diminished the degree of calcium accumulation and reactive oxygen species generation during the period of metabolic inhibition. The improvement in calcium homeostasis was traced in part to the downregulation of the CaV3.1 T-type calcium channel, as deficiency in the CaV3.1 subtype using short hairpin RNA or treatment with an inhibitor of the CaV3.1 variant of the T-type calcium channel (i.e., diphenylhydantoin) attenuated energy deficiency-mediated calcium accumulation and cell death. Although hyperosmotically stressed cells (exposed to 50 mM mannitol) had no effect on T-type calcium channel activity, they were also resistant to death during metabolic inhibition. Both hyperosmotic stress and hypernatremia activated Akt, suggesting that they initiate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt cytoprotective pathway, which protects the cell against calcium overload and oxidative stress. Thus hypernatremia appears to protect the cell against metabolic inhibition by promoting the downregulation of the T-type calcium channel and stimulating cytoprotective protein kinase pathways.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, neonatal cardiomyocytes, apoptosis, ribonucleic acid interference, calcium homeostasis, diphenylhydantoin

hypernatremia, which is a pathological condition predominantly characterized by excessive water loss and elevated serum sodium, is present in numerous disease states, including diabetes insipidus, diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, renal dysfunction, and drug toxicity. While elevated serum sodium has been commonly linked to hypertension, sodium also serves as a key inorganic osmolyte and through the actions of the Na+/H+ and the Na+/Ca2+ exchangers a determinant of pHi and intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i). Because contractile function is regulated by pHi and [Ca2+]i, defects in sodium homeostasis invariably alter muscle and cardiac function.

The actions of elevated serum sodium are complex, and their interactions with ischemic injury remain unclear. One factor to consider is that ischemia itself causes elevations in intracellular sodium concentration ([Na+]i) related to reductions in Na+-K+-ATPase activity (14). Another consequence of ischemia is the accumulation of intracellular osmolytes, such as lactate and inorganic phosphate, which initially trigger osmotic imbalances that cause the cell to swell (12). The resulting osmotic stress increases the likelihood that damaged membranes will rupture, a common event in ischemia (7, 27, 35). Also triggered during ischemia are arrhythmias and contractile dysfunction, conditions that further deteriorate in response to cell stretching (7). Therefore, it is not surprising that perfusion of the ischemic heart with a hyperosmotic solution might improve the outcome of an ischemia-reperfusion insult (7).

While an acute elevation in extracellular osmolarity protects the ischemic heart by restoring the osmotic balance across the cell membrane, a mild, chronic elevation in the extracellular-to-intracellular osmolarity ratio appears to render the heart resistant to an ischemic event. We (1, 34) have previously shown that chronic reductions in the intracellular levels of the organic osmolyte taurine protect the heart against an ischemic insult, in part by reducing [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i. Moreover, taurine depletion leads to the activation of the cytoprotective phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase)/Akt pathway (22). Interestingly, preincubation of isolated cardiomyocytes with medium containing 50 mM mannitol also enhances flux through the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway and protects the energy-depleted cell, suggesting that elevations in extracellular osmolarity also activate cytoprotective signaling pathways (20). A potential protective effect of hyperosmotic stress involving a PI3-kinase- and p21-activated kinase (PAK)-dependent pathway has recently been described (3).

Therefore, sodium excess mediates multiple and competing effects on the cardiomyocyte. Not only does it directly alter the ionic composition of the intracellular and extracellular milieu, but it also promotes osmotic stress. During the course of the present study, we discovered that an elevation in extracellular sodium reduces the expression of the T-type Ca2+ channel, a transporter that appears to increase basal [Ca2+]i of the hypoxic neonatal cardiomyocyte. In light of this new discovery, the present study examined the hypothesis that elevations in extracellular sodium render the cardiomyocyte resistant to metabolic inhibition through its ability to cause osmotic stress and to modulate the activity of ion transporters that affect [Ca2+]i.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cardiomyocyte preparation and incubation conditions.

Neonatal cardiomyocytes were prepared as described previously (24, 33, 34). The cells were suspended in MEM containing 10% newborn calf serum and 0.1 mM 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine and allowed to plate on either glass coverslips or polystyrene-treated Petri dishes at a density of ∼10 × 106 cell/dish (10-cm diameter). They were then placed in serum-free medium containing MEM supplemented with no addition (control, contains 142 mM sodium), elevated sodium (hypernatremia, contains 167 mM sodium), or 50 mM mannitol (osmotic control). MEM also contains 1.8 mM Ca2+, 0.8 mM Mg2+, and 5.33 mM K+. All experiments were initiated after a 3-day incubation at 37°C under a 5% CO2-20% O2 environment. The study adheres to American Physiological Society's Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals.

Induction of metabolic inhibition.

In most experiments, metabolic inhibition was induced by transferring cells to medium lacking glucose, containing 142 mM Na+, and supplemented with 10 mM deoxyglucose and 3 mM amobarbital. Glucose and fatty acids were eliminated from the medium to restrict the generation of NADH and FADH by glycolysis and fatty acid β-oxidation. Deoxyglucose was added to the medium to block the utilization of glycogen breakdown products by the glycolytic pathway. Amobarbital, a complex I inhibitor, was added to the medium to prevent the utilization of NADH by the electron transport chain. Because the metabolic inhibitory medium contains normal 142 mM Na+ while some of the cells were preincubated with medium containing 167 mM Na+, the effect of metabolic inhibition is examined in a hypernatremic preconditioned cell.

Cells exposed to amobarbital and deoxyglucose rapidly become energy deficient. Because ATP is essential for maintaining ion homeostasis, metabolic inhibition leads to a rapid increase in the cellular levels of sodium, calcium, and magnesium (32, 36). The model has been employed to evaluate cytoprotective agents and maneuvers (30, 33) and to induce preconditioning (17). Metabolic inhibition, which leads to severe ATP deletion and impaired electron transport, resembles the ischemic phase of an ischemia-reperfusion insult.

A modified version of the metabolic inhibition model can be used to evaluate the modulation of oxidative stress. In the modified version of the model, the medium is supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 3 mM amobarbital but no deoxyglucose. The metabolism of glucose provides a source of NADH for utilization by NADH dehydrogenase of complex I. Amobarbital acts like other complex I inhibitors to stimulate superoxide production. Therefore, the modified model leads to both energy deficiency and oxidative stress.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end labeling procedure.

The Klenow Frag EL DNA fragmentation detection kit was used to monitor end-labeled DNA fragments of apoptotic nuclei. Cells were assayed for positive terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end staining before and after 1 h of metabolic inhibition. Four separate fields in the light microscope were examined for dark brown (apoptotic) and purple (normal) nuclei.

Measurement of superoxide levels using dihydroethidium.

Control and high sodium-treated neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated with dihydroethidium (5 μM), which is oxidized to ethidium in the presence of superoxide. After 1 h, the dye-containing media were removed and replaced with fresh media. Cells were then incubated for an additional 30 min before analysis. Some cells from each group were then exposed to modified metabolic inhibitory medium containing or lacking diphenylhydantoin (100 μM; see above). Changes in ethidium fluorescence were monitored by confocal microscopy at 5-min intervals, with at least 10 groups of cells monitored per sample (29). The complex I inhibitor amobarbital blocks the electron transport chain, causing the diversion of electrons from the electron transport chain to oxygen, forming in the process superoxide.

Western blot analyses.

The cellular content of caspase-9, total Akt, pAkt, T-type Ca2+ channel Cav3.1 variant, and β-actin was determined by Western blot analyses as described previously (22, 24, 33). The protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method using BSA as a standard. All densitometric data were analyzed by computer program that measured the intensity of the band. Gels were also analyzed by Ponceau's solution to ensure equal protein loading.

Cellular Ca2+ content.

Basal cellular [Ca2+]i was determined with the Ca2+-sensitive fluorophore fura-2/acetoxymethylester according to the methods described previously (24). During metabolic inhibition, cell beating and the generation of Ca2+ transients ceased. Although Ca2+ transients are generated in cells before exposure to the metabolic inhibitors, all of the data are expressed as the basal F340-to-F380 ratio (F340/F380). When the effect of the T-type Ca2+ channel blocker diphenylhydantion was examined, the antagonist was added to medium containing the metabolic inhibitors.

Electrophysiological recording.

Conventional whole cell voltage-clamp configurations were used as described previously (24). The extracellular (bath) solution contained the following (in mmol/l): 2 CaCl2, 110 tetraethylammonium chloride, 10 CsCl, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4, adjusted with tetraethylammonium hydroxide). The intracellular (pipette) solution contained the following (in mmol/l): 130 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 10 EGTA, 5 BAPTA, 10 HEPES, 6 MgCl2, 4 CaCl2, and 2 Mg-ATP (pH 7.2, adjusted with methane sulfonic acid). All solutions were adjusted to 290–300 mosM with sucrose.

Lentivirus transduction.

Lentiviral short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), which target the rat Cav3.1 variant, and an unrelated (scrambled) shRNA were obtained from Open Biosystem. DNA fragments encoding shRNAs for Cav3.1 and scrambled shRNA were subcloned from the pLKO.1 backbone into the lentiviral backbone containing a synthetic mCherry gene that was driven by the CMV promoter; the mCherry gene allowed the shRNA-expressing cells to be tracked by red fluorescence (23). Lentivirus-containing supernatant was produced by transfection of HEK293T cells in the presence of packaging plasmids pMD2.G and psPAX2 (Addgene). Virus-containing supernatant was collected at 24, 36, and 48 h after transfection and filtered through 0.45-μm filters. To mediate cardiomyocyte transduction, cells were infected with harvested virus supernatant from the packaging cells. The transduction efficiency was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus IX 70 inverted microscope.

Quantitative real-time PCR method of measuring levels of T-type Cav3.1 channel variant.

Total RNA was isolated according to protocol from cells using TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was then performed according to protocol using the iScript One-Step RT-PCR kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences were designed to amplify 150- to 200-bp sequences within the specific sequences of the selected genes as follows. Primer sequences were as follows: Cav3.1: forward, 5′-gcaacattgtggtcatttcg-3′ and reverse, 5′-tgatgttcctggtgtcctca-3′; and 28S rRNA: forward, 5′-gattcccactgtccctacc-3′ and reverse, 5′-acctctcatgtctcttcacc-3′.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between two groups and between three or more means within each group was determined by first using two-way ANOVA and one way ANOVA, respectively. Both analyses were combined with the Dunnett's multiple comparison test (comparing all columns vs. the control column) to establish significance. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

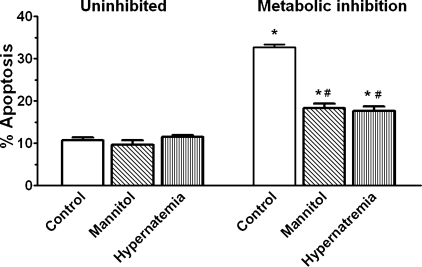

To evaluate the effect of high sodium, isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes maintained for 3 days in medium containing either elevated sodium {hypernatremia group, 167 mM extracellular ([Na+]o)} or normal sodium (untreated control, 142 mM [Na+]o) were studied. Some of the hypernatremic and control cells were transferred to medium containing 142 mM [Na+]o and supplemented with the metabolic inhibitors amobarbital and deoxyglucose. Because the medium supplemented with amobarbital and deoxyglucose contains normal Na+ (142 mM), the experiment examines the ability of hypernatremia to precondition the cell against injury mediated by metabolic inhibition. Figure 1 shows that after 1 h of metabolic inhibition, 33% of the untreated control cells and 18% of the high sodium-treated cells (167 mM [Na+]o) were apoptotic; the number of apoptotic cells in the metabolically uninhibited groups was ∼10%.

Fig. 1.

Effect of hyperosmotic stress and hypernatremia on apoptosis mediated by metabolic inhibition. Cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days with medium containing either no additions (control, contains 142 mM Na+), 167 mM total Na+ (hypernatremia), or 50 mM mannitol (mannitol), the latter to mimic the osmotic stress component of hypernatremia, which involves an increase of 25 mM Na+ and 25 mM Cl−. Some of the cells were subjected to 1 h of metabolic inhibition (in medium containing 142 mM Na+ and the metabolic inhibitors) and examined for apoptosis [terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP-mediated nick-end (TUNEL) staining]. Values are means ± SE of 5 different preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference from the uninhibited control. #P < 0.05, significant difference from the metabolically inhibited control.

To determine whether the hyperosmolar nature of the hypernatremic medium contributed to the observed cytoprotection, some cells were incubated for 3 days in medium containing 50 mM mannitol (the same osmolarity as the hypernatremic group) before being transferred to medium containing the metabolic inhibitors. As expected, the osmotically stressed cells also exhibited a significant reduction in cell death upon exposure to the metabolic inhibitors (Fig. 1), suggesting that the beneficial effect of hypernatremia is mediated in part by chronic hyperosmotic stress.

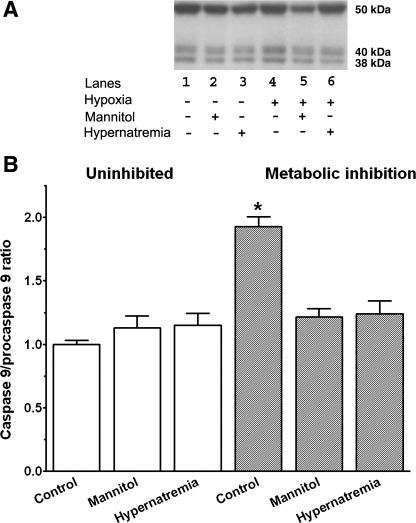

A major cause of cell death in the metabolically inhibited neonatal cardiomyocyte is initiation of the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) and the subsequent activation of the caspase cascade. To determine if hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress affected mitochondrial apoptosis, the activation state of caspase-9 was examined after 1 h of metabolic inhibition. As seen in Fig. 2, metabolic inhibition significantly increased the amount of active caspase-9 (38 kDa) relative to the inactive precursor (procaspase-9, 50 kDa). However, the caspase-9 activation ratio (caspase-9 to procaspase-9) was diminished in the hypernatremic and hyperosmotically stressed cells compared with the metabolically inhibited control cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress on activation of caspase-9 by metabolic inhibition. Control, hypernatremic, and hyperosmotically stressed cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days as described in Fig. 1. They were then subjected to 1 h of metabolic inhibition. Cells obtained before and following metabolic inhibition for 1 h were harvested, and Western blot analyses for procaspase-9 (50 kDa) and for the active form of caspase-9 (38 kDa) were then performed. A: representative Western blots of procaspase-9 and active caspase-9. B: relative ratio of active caspase-9 to procaspase-9. The ratio of the uninhibited control was set at 1.0. Values are means ± SE of 3–4 separate preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between uninhibited control and metabolically inhibited control cells.

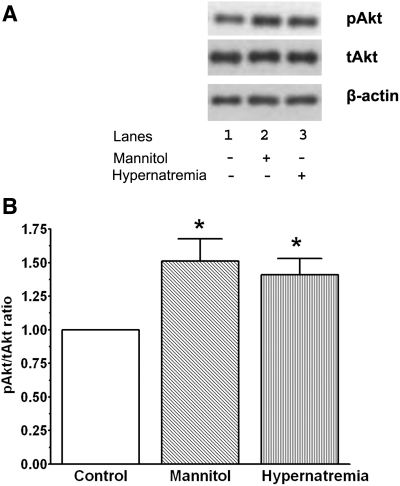

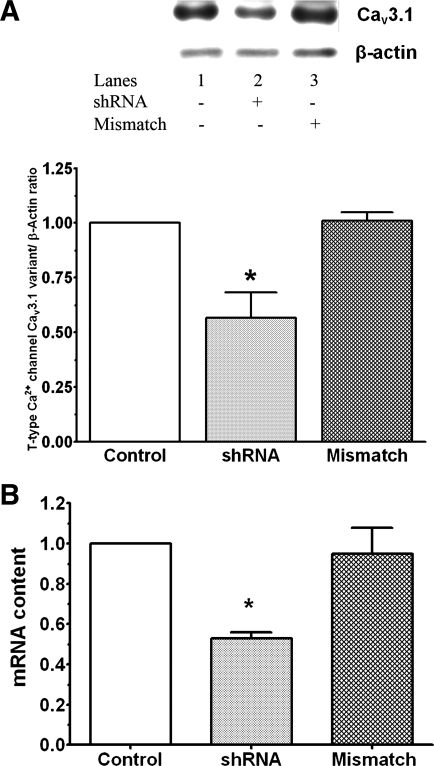

We (22) have previously shown that hyperosmotic stress leads to the activation of the cytoprotective PI3-kinase/Akt pathway. To determine if hypernatremia also actives Akt, the phosphorylation state of Akt was examined in cells that had been incubated for 3 days in medium containing normal sodium (142 mM [Na+]o), elevated sodium (167 mM [Na+]o), or elevated osmolarity (50 mM mannitol but 142 mM [Na+]o). As seen in Fig. 3, neither hyperosmotic stress nor hypernatremia altered total Akt content, but both conditions significantly increased the phosphorylation state of Akt, raising the possibility that stimulation of the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway might contribute to the cytoprotective effects of hyperosmotic stress and hypernatremia.

Fig. 3.

Effect of hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress on the phosphorylation status of Akt. Control, hypernatremic, and hyperosmotically stressed cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days as described in Fig. 1. Cells were then harvested and Western blot analyses of Akt and phospho-Akt were performed. A: representative Western blots of phospho-Akt (pAkt), total Akt (tAkt), and β-actin. B: relative pAkt-to-tAkt ratio. The ratio of the control was set at 1.0 after being normalized relative to β-actin levels. Values are means ± SE of 4 separate preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between hypernatremic and hyperosmotic cells and the control cells.

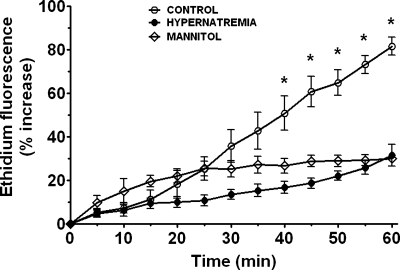

The PI3-kinase/Akt pathway protects the hypoxic cardiomyocyte by attenuating the formation of the MPT pore (4, 21). Because one of the dominant factors involved in MPT pore formation and opening during ischemia and hypoxia is oxidative stress, we examined the effect of hypernatremia on oxidative stress. Many complex I inhibitors promote oxidative stress in the mitochondria when the supply of electron donors for the electron transport chain is adequate (29); therefore, the composition of the metabolically inhibited medium was modified by adding 10 mM glucose as a source of NADH in addition to the complex I inhibitor amobarbital. As seen in Fig. 4, the rate of superoxide generation, as well as the maximum amount of superoxide generated during metabolic inhibition, was diminished in both the hypernatremic and osmotically stressed cells. Since MitoSox fluorescence, which is specific for mitochondrial superoxide generation, was also diminished by hypernatremia (data not shown), the cytoprotective mechanism appears to reduce a mitochondrial source of superoxide production.

Fig. 4.

Effect of hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress on superoxide generation. Control and hypernatremic cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days as described in Fig. 1. They were then loaded for 1 h with the superoxide sensitive dye dihydroethidium (5 μM). Baseline values of ethidium fluorescence, a measure of cellular superoxide, were monitored by confocal microscopy. Cells were then subjected to metabolic inhibition in medium containing amobarbital and glucose. Changes in ethidium fluorescence were assessed at 5-min intervals. Values are means ± SE of 4–7 different preparations, with at least 10 cells monitored per culture dish. *P < 0.05, significant difference between control and both stressed groups.

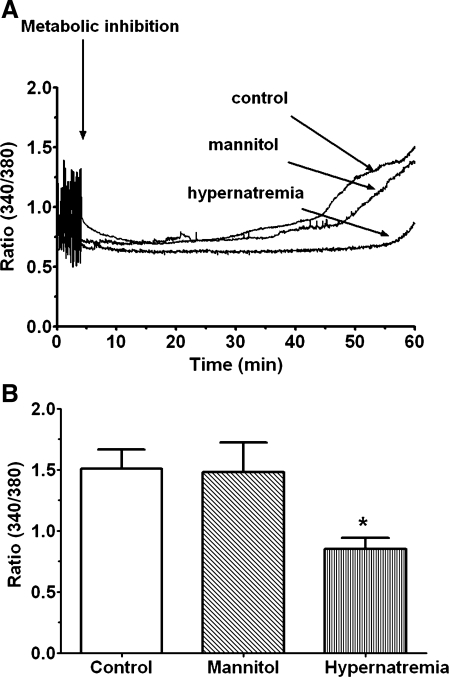

Another important initiator of the MPT in hypoxic cells is Ca2+ overload (8, 14). Therefore, we examined the possibility that hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress might reduce the degree of Ca2+ accumulation in the metabolically inhibited cell. We have previously shown that shortly after exposure to medium containing amobarbital and deoxyglucose, cell contraction and the generation of Ca2+ transients cease and resting [Ca2+]i remains largely unaltered for ∼30 min. This period of steady-state [Ca2+]i is followed by an exponential rise in resting [Ca2+]i, with the change in [Ca2+]i dependent on both the rate of [Ca2+]i rise and the time at which the rise was initiated. Figure 5 reveals that cells treated chronically with hypernatremic medium exhibit a delayed onset of Ca2+ accumulation and a reduced rate of [Ca2+]i rise. However, the untreated control cells exhibit a massive exponential rise in [Ca2+]i. Consequently, after 60 min of metabolic inhibition, hypernatremic cells contained 40% less [Ca2+]i than the untreated control cells. On the other hand, no significant difference exists between control and hyperosmotically stressed (i.e., mannitol-exposed) cells, either in terms of the rate or the overall amount of Ca2+ accumulated during metabolic inhibition (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress on Ca2+ accumulation by the metabolically inhibited cell. Control, hypernatremi,c and hyperosmotically stressed cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days as described in Fig. 1. Cells were then loaded with the calcium probe fura-2. Fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm was measured before metabolic inhibition, and data were expressed as the fluorescence ratio (F340/F380), a measure of Ca2+ content. Cells were then subjected to metabolic inhibition, and F340/F380 was continuously monitored. A: representative tracing of F340/F380 for control and hypernatremic cells. B: cumulated data of F340/F380 after 60 min of metabolic inhibition. Data are means ± SE of 5 separate preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between the hypernatremic group and the control cells.

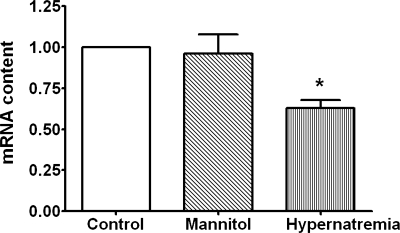

Influx of Ca2+ via the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels is an important contributor to the rise in [Ca2+]i in the energy-deficient cell (16, 17, 20, 31). The most active of these Ca2+ transporters in the fully depolarized cardiomyocyte is the L-type Ca2+ channel. However, the L-type Ca2+ channel mediates Ca2+ entry at a membrane potential that is positive of −30 mV, in contrast to the T-type Ca2+ channel that opens at a voltage positive of −70 mV (26). Thus a slight depolarization of the cell allows Ca2+ influx via the T-type Ca2+ channel to proceed but not flux via the L-type Ca2+ channel. To determine if T-type Ca2+ channel function might contribute to Ca2+ overload in the metabolically inhibited neonatal cardiomyocyte, the effect of hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress on the expression and activity of the T-type Ca2+ channels was measured. As seen in Fig. 6, cardiomyocytes incubated for 3 days with medium containing 167 mM [Na+]o exhibited a decrease in the mRNA content of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel subtype. Hypernatremia also led to a decrease in the activity of the low voltage-activated Ca2+ channel (Tb type) but did not affect the high voltage-activated Ca2+ current (L type; Fig. 7). By comparison, hyperosmotic stress affected neither the mRNA levels of the Cav3.1 variant nor the activity of the low voltage-activated Ca2+ current (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6.

Effect of hypernatremia and osmotic stress on the expression of the T-type Ca2+ channel. Control, hypernatremic, and hyperosmotically stressed cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days as described in Fig. 1. Cells were harvested, and total RNA was isolated with TRIzol. Quantitative real-time PCR of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel variant was performed using the iScript One-Step real-time-PCR kit with SYBR green. Values are means ± SE of 5 preparations. Control value was set to 1.0. *P < 0.05, significant difference between the mRNA content of the hypernatremic cells and that of the other 2 groups.

Fig. 7.

Effect of hypernatremia and hyperosmotic stress on T-type Ca2+ current. Control, hypernatremic and hyperosmotically stressed cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days as described in Fig. 1. Properties of the L-type (IL) and T-type (IT) Ca2+ channels were then evaluated. I-V curves (of peak currents) represent the measurements made at holding potentials of −40 mV (bottom) and the difference between the measurements made at −90 and −40 mV (top) from control (○), hypernatremic (●), or mannitol-treated (□) cardiomyocytes. Vm, membrane potential.

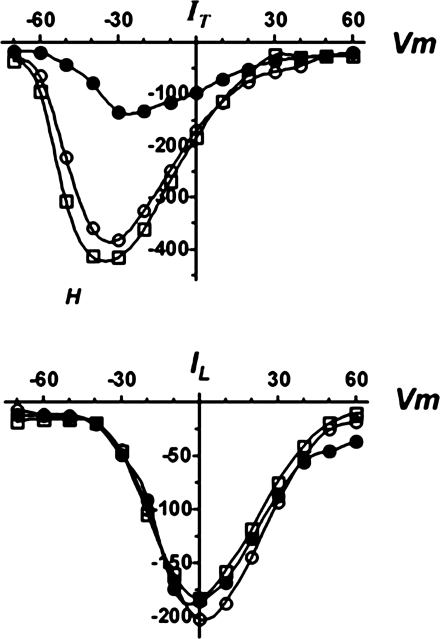

To evaluate the importance of the hypernatremia-mediated change in Cav3.1 content, cellular Cav3.1 levels were also diminished using shRNA. The reason for focusing on the Cav3.1 subtype was the observation that hypoxia significantly decreases the activity of the Cav3.2 subtype (5). Based on Western blot and real-time PCR analyses of cells treated with the shRNA-expressing lentivirus, cellular protein and mRNA levels of the Cav3.1 variant fell ∼40%, a decline similar in magnitude to that seen with hypernatremia (Figs. 6 and 8). However, cells treated with control lentivirus (mismatched shRNA) showed no change in mRNA and protein content of the Cav3.1 variant (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Effect of short hairpin (sh)RNA on the expression of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel. Isolated cardiomyocytes were incubated with medium containing or lacking shRNA for Cav3.1; some cells were incubated with a scrambled shRNA. A: cells were harvested and Western blot analyses of the Cav3.1 variant and β-actin were performed. Top: representative Western blots for Cav3.1 and β-actin. Bottom: protein content of the Cav3.1 variant normalized to β-actin content. The normalized value for the Cav3.1 variant in the control cells was set at 1.0. B: cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated. Real-time PCR was performed as described in Fig. 6. Values are means ± SE of 4–6 preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between the shRNA-treated group and both the untreated control and the mismatched control.

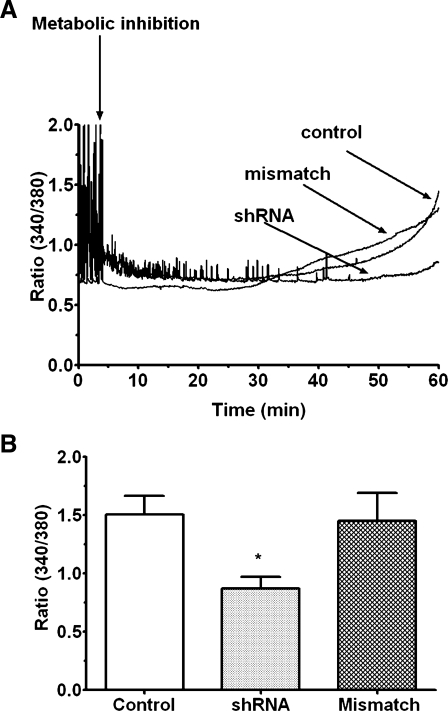

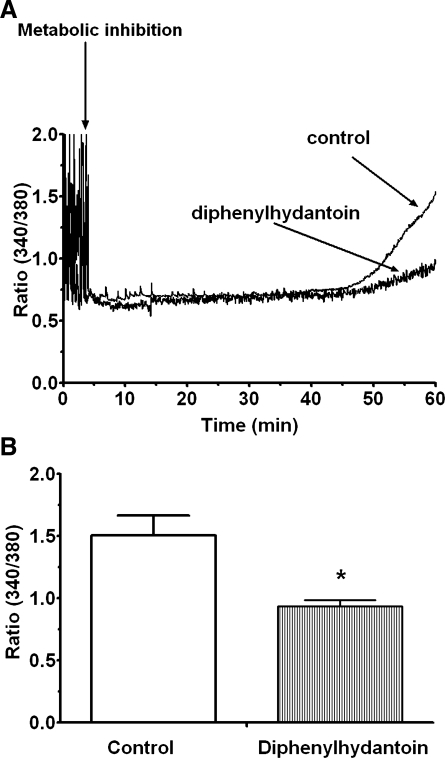

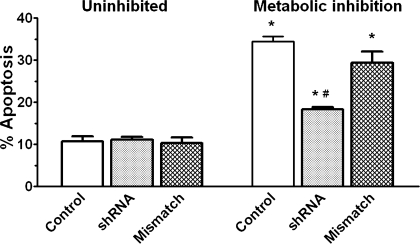

The effect of Cav3.1 deficiency on Ca2+ accumulation by the energy-deficient cell was then determined. Figure 9 reveals that deficiency of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel attenuated the accumulation of Ca2+ in the metabolically inhibited neonatal cardiomyocyte. As seen in Fig. 9, contractile function and the generation of Ca2+ transients of the control and mismatched cells ceased shortly after the initiation of metabolic inhibition. Similarly, both the generation of Ca2+ transients and contractile function of 60% of the Cav3.1-deficient cells ceased shortly after the onset of metabolic inhibition. However, in the remaining 40% of the Cav3.1-deficient cells, metabolic inhibition reduced the frequency of the Ca2+ transients but the cells continued to beat. Approximately 30 min after the cessation of contractile function, [Ca2+]i began to increase exponentially in the metabolically inhibited control and scrambled shRNA-transfected cells. By contrast, virtually all of the Cav3.1-deficient cells exhibited a delay in the exponential increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 9). Accordingly, F340/F380 did not change in the Cav3.1-deficient cells 60 min after the onset of metabolic inhibition, while F340/F380 in the mismatched and untreated control cells increased twofold (Fig. 9). A similar pattern was observed in cells exposed to an inhibitor of the Cav3.1 variant of the T-type Ca2+ channel, diphenylhydantoin (100 μM), throughout the experimental protocol. The rate of [Ca2+]i rise in the diphenylhydantoin-treated cells was diminished during metabolic inhibition, resulting in a significant decrease (35%) in F340/F380 after 60 min of energy deficiency (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

Effect of shRNA on Ca2+ accumulation by the metabolically inhibited cell. Cardiomyocytes were treated with either shRNA directed against the Cav3.1 variant of the T-type Ca2+ channel or with mismatched shRNA. After cells were loaded with fura-2, F340/F380, which is a measure of intracellular calcium concentration, was measured in uninhibited cells. Cells were then subjected to metabolic inhibition, and F340/F380 was monitored for 60 min. A: representative tracing for shRNA-treated cells, mismatched shRNA-treated cells, and control cells. B: cumulative values for F340/F380. Values are means ± SE of 3–4 preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between the shRNA treated group and the other two control groups.

Fig. 10.

Effect of diphenylhydantoin on Ca2+ accumulation by the metabolically inhibited cell. Cardiomyocytes were incubated for 3 days with control medium as described in Fig. 1. After cells were loaded with fura-2, F340/F380 was determined in the uninhibited cells. Cells were then exposed to 1 h of metabolic inhibition in medium containing or lacking an inhibitor of the Cav3.1 variant of the T-type Ca2+ channel (diphenylhydantoin, 100 μM). The F340/F380 of the cells was monitored throughout the period of metabolic inhibition. A: representative tracing for control and diphenylhydantoin-treated cells. B: cumulative values for F340/F380. Values are means ± SE of 4 different preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between the diphenylhydantoin treated and untreated cells.

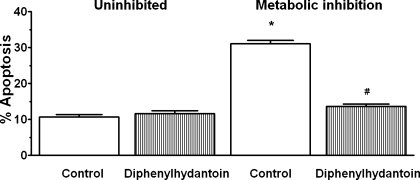

The Cav3.1-deficient cells were also resistant to apoptosis mediated by metabolic inhibition (Fig. 11). While 20–25% of the untreated and mismatched control cells underwent apoptosis during 1 h of metabolic inhibition, only 9% of the Cav3.1-deficient cells became apoptotic in response to severe energy depletion. Diphenylhydantoin is also an effective inhibitor of apoptosis in the metabolically inhibited cell; only ∼2% of the diphenylhydantoin treated cells became apoptotic during the period of metabolic inhibition (Fig. 12).

Fig. 11.

Effect of shRNA on apoptosis mediated by metabolic inhibition. Cardiomyocytes were treated with shRNA or scrambled shRNA. After an overnight incubation with normal medium, cells were incubated with medium containing amobarbital and deoxyglucose for 1 h and then examined for the presence of apoptotic cells (TUNEL staining). Values are means ± SE of 5 different preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between the uninhibited control and the metabolically inhibited control. #P < 0.05, significant difference between the metabolically inhibited shRNA group and the other 2 metabolically inhibited groups.

Fig. 12.

Effect of diphenylhydantoin on apoptosis mediated by metabolic inhibition. After a 3-day incubation with control medium, the cells were transferred to medium containing amobarbital and deoxyglucose supplemented with either 0 or 100 μM diphenylhydantoin. After 1 h the cells were examined for the presence of apoptotic cells (TUNEL staining). Values are means ± SE of 4 different preparations. *P < 0.05, significant difference between the metabolically inhibited and uninhibited control. #P < 0.05, significant difference between the metabolically inhibited, diphenylhydantoin-treated group, and uninhibited, diphenylhydantoin-treated group.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that cells chronically incubated with medium containing elevated sodium undergo phenotypical changes that render them resistant to metabolic inhibition. This finding was initially unanticipated, as the only other study examining the effects of elevated extracellular sodium on infarct size reported an adverse effect of hypertonic saline on focal cerebral ischemic injury (2). However, there are major differences between the two studies, with one of the most important being the design of the experiment. In the study by Bhardwaj et al. (2), the preparation was exposed to hypertonic saline throughout the cerebral ischemic insult, while in the present study isolated cardiomyocytes were only exposed to elevated Na+ during the uninhibited period. This is an important difference because the initial response to high Na+ is cell shrinkage, but during the course of the 3-day incubation, regulatory changes lead to the virtual normalization of cell volume and [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5). By contrast, the presence of elevated [Na+]o during metabolic inhibition retards the efflux of Na+ via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, resulting in a rise in [Na+]i to toxic levels. The accumulation of Na+ and other osmolytes in the energy-deficient cell leads to osmotic imbalances that cause the cell to swell, which often leads to cell membrane damage.

Another important factor damaging hypoxic and energy-deficient cells is Ca2+ overload. Besides promoting protease activation, the rise in [Ca2+]i also contributes to the initiation of the MPT (9). In the adult cardiomyocyte, the major cause of elevated [Ca2+]i during hypoxia is enhanced flux through the Na+/H+ and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (13). Influx of Ca2+ via the L-type Ca2+ channel requires greater depolarization of the hypoxic cell to reach a membrane potential that permits L-type Ca2+ channel opening. However, in the neonatal cardiomyocyte, the presence of an abundant supply of two T-type Ca2+ channel variants (Cav3.1 and Cav3.2), which open at a more negative membrane potential than the L-type Ca2+ channel, raises the possibility that increased influx of Ca2+ via the low voltage-activated Ca2+ channels might contribute to the rise in [Ca2+]i in the energy-deficient cell. To test the feasibility of this idea, we examined the effects of the inhibitor of the Cav3.1 variant of the T-type Ca2+ channel, diphenylhydantoin (15), and of cellular Cav3.1 knockdown on accumulation of Ca2+ during metabolic inhibition. Despite the 40% decrease in Cav3.1 levels in cells infected with lentivirus encoding shRNA directed against Cav3.1, the Cav3.1-deficient cells displayed a normal beating pattern, although they accumulated less Ca2+, exhibited a muted exponential rise in [Ca2+]i, and remained more viable when subjected to metabolic inhibition (Figs. 9 and 11). A similar pattern was observed with cells exposed to a T-type Ca2+ channel blocker, such as diphenylhydantoin (100 μM) or kurtoxin (1 μM) (Figs. 10 and 12, kurtoxin data not shown). These findings show for the first time that the T-type Ca2+ channel, when available, serves as an important transporter of Ca2+ in the energy-deficient cell.

Another interesting finding of the present study is that hypernatremia diminishes the activity of the T-type Ca2+ channel. Because hypernatremic cells exhibit a similar decline in the mRNA and protein levels of Cav3.1 as shRNA-treated cells, we anticipated that the Cav3.1-deficient cell would exhibit a muted response to metabolic inhibition. This assumption was confirmed, as evidenced by the reduced rate in [Ca2+]i rise and the decline in cell death of both the hypernatremic and shRNA-treated cells (Figs. 1, 9, and 11). Also supporting a role for Cav3.1 in Ca2+ accumulation of the hypernatremic cardiomyocyte is the observation that hyperosmotic stress, which does not regulate the expression of the Cav3.1 subtype, has a limited ability to reduce the extent of Ca2+ accumulation by the energy-depleted cell (Figs. 5 and 6).

In contrast to the neonatal cell, two findings have raised questions regarding the importance of the T-type Ca2+ channel in the adult heart. First, evidence supporting a role for the T-type Ca2+ channel in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the adult heart is inconclusive because it is based on experiments using the T-type Ca2+ channel blocker mibedfradil whose specificity has been challenged. Second, the activity of the T-type Ca2+ channel is much lower in the healthy adult heart than the healthy neonatal heart (6). Nonetheless, in certain pathological conditions, such as cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, the expression of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel is upregulated (13, 37). Therefore, further experiments examining the contribution of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel toward ischemia-mediated Ca2+ overload in the pathological heart are warranted.

Another important finding of the present study is that hypernatremia reduces the generation of the superoxide anion by the metabolically inhibited cardiomyocyte (Fig. 4). In contrast to the effect of chronic hypernatremia on cellular cation content, the change in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels is seemingly unrelated to the cationic imbalance caused by the increase in [Na+]o. Rather, the change in ROS levels is more closely associated with the elevation in extracellular osmolarity, which prompts the osmotically stressed cell to trigger a series of events that minimize the consequences of the hyperosmotic stress. One of the effectors activated in response to hyperosmotic stress is protein kinase C-ε (PKC-ε; Refs. 11, 22). In the cardiomyocyte, PKC-ε is recognized as a key component of the reperfusion injury salvage kinase pathway, the cytoprotective pathway initiated by ischemic preconditioning (10). PKC, which lies downstream from PI3-kinase and Akt in the reperfusion injury salvage kinase pathway, mediates the cytoprotective actions of ischemic preconditioning by preventing MPT pore opening (10). In this regard, it is significant that both hypernatremia stress and hyperosmotic stress also activate Akt (Fig. 3). These observations are in accordance with previous studies (1, 22, 34) that have demonstrated that hyperosmotic stress arising from the depletion of the cellular osmolyte taurine also leads to a preconditioned state, characterized by reductions in infarct size, hypoxia-mediated Ca2+ accumulation, and apoptosis. Similarly, chronic exposure of cardiomyocytes to medium containing 25 mM glucose (as opposed to 5 mM glucose) renders the cells resistant to cell death mediated by metabolic inhibition (33), an effect also associated with a decrease in Ca2+ accumulation, an upregulation of Bcl-2, an inactivation of BAD, and an activation of PI3-kinase, Akt and PKC-ε (28, 33). Thus hypernatremia stress and hyperosmotic stress activate some of the same cytoprotective pathways that reduce ischemia-linked Ca2+ accumulation and ROS generation in the adult heart (10, 25).

Perspectives

The present study reveals a potential role for the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Neonatal cardiomyocytes, which contain abundant levels of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel, accumulate large amounts of Ca2+ when subjected to a metabolic inhibitory insult that is accompanied by a decrease in Na+-K+-ATPase activity. This effect is abolished in cardiomyocytes containing reduced levels of the Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel or in cells treated with an inhibitor of the Cav3.1 variant of the T-type Ca2+ channel, diphenylhydantoin. Because preconditioning of the cell with medium containing elevated Na+ attenuates intracellular Ca2+ accumulation, the cytoprotection associated with hypernatremic preconditioning appears to be linked to an improvement in Ca2+ homeostasis. Therefore, the possibility that preconditioning protects the adult heart against ischemia in part by improving Ca2+ homeostasis deserves further consideration. Also of interest is the effect of diphenylhydantoin on Ca2+ homeostasis in the ischemic adult heart. The possibility that diphenylhydantoin might serve as an important therapeutic modality in the treatment of ischemic heart disease is worthy of consideration.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-66299 (to S. Wu) and American Heart Association Grant 0755288B (to S. W. Schaffer).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allo SN, Bagby L, Schaffer SW. Taurine depletion, a novel mechanism for cardioprotection from regional ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H1956–H1961, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhardwaj A, Harukuni I, Murphy SJ, Alkayed NJ, Crain BJ, Koehler RC, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ. Hypertonic saline worsens infarct volume after transient focal ischemia in rats. Stroke 31: 1694–1701, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan PM, Lim L, Manser E. PAK is regulated by PI3K, PIX, CDC42 and PP2alpha and mediates focal adhesion turnover in the hyperosmotic stress-induced p38 pathway. J Biol Chem 283: 24949–61, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa ADT, Pierre SV, Cohen MV, Downey JM, Garlid KD. cGMP signalling in pre- and post-conditioning: the role of mitochondria. Cardiovasc Res 77: 344–352, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fearon IM, Randall AD, Perez-Reyes E, Peers C. Modulation of recombinant T-type Ca2+ channels by hypoxia and glutathione. Pflügers Arch 441: 181–188, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferron L, Capuano V, Deroubaix E, Coulombe A, Renaud JF. Functional and molecular characterization of a T-type Ca2+ channel during fetal and postnatal rat heart development. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 533–546, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Dorado D, Oliveras J. Myocardial Oedema: a preventable cause of reperfusion injury? Cardiovasc Res 27: 1555–1563, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths EJ, Bell CJ, Balaska D, Rutter GA. Mitochondial calcium: role in the normal and ischaemic/reperfused myocardium. In: Mitochondria: the Dynamic Organelle, edited by Schaffer SW, Suleiman MS. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2007, p. 197–220 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halestrap AP. What is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore? J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 821–831, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Preconditioning and postconditioning: united at reperfusion. Pharmacol Ther 116: 173–191, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinzinger H, van den Boom F, Tinel H, Wehner F. In rat hepatocytes, the hypertonic activation of the Na+ conductance and Na+-K+-2Cl- symport-but not Na+-H+ antiport is mediated by protein kinase C. J Physiol 536: 703–715, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol Rev 89: 193–277, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang B, Qin D, Deng L, Boutjdir M, El-Sherif N. Reexpression of T-type Ca2+ channel gene and current in post-infarction remodeled rat left ventricle. Cardiovasc Res 46: 442–449, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karmazyn M, Gan XT, Humphreys RA, Yoshida H, Kusumoto K. The myocardial Na+-H+ exchange: structure, regulation and its role in heart disease. Circ Res 85: 777–786, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacinova L. Pharmacology of recombinant low-voltage activated calcium channels. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 3: 105–11, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DS, Goodman S, Dean DM, Lenis J, Ma P, Gervais PB, Langer A. Randomized comparisonof T-type versus L-type calcium channel blockade on exercise duration in stable angina: results of the Posicor reduction of ischemia during exercise (PRIDE) trial. Am Heart J 144: 60–67, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Tsang S, Wong TM. Testosterone is required for delayed cardioprotection and enhanced heart shock protein 70 expression induced by preconditioning. Endocrinology 147: 4569–4577, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo HM, Kloner RA, Braunwald E. Effect of intracoronary verapamil on infarct size in the ischemic, reperfused canine heart: critical importance of the timing of treatment. Am J Cardiol 56: 672–677, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lory P, Chemin J. Towards the discovery of novel T-type calcium channel blockers. Expert Opin Ther Targets 11: 717–22, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller CA, Opie LH, McCarthy J, Hofmann D, Pineda CA, Peisach M. Effects of mibefradil, a novel calcium channel blocking agent with T-type activity, in acute experimental myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 32: 268–274, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev 88: 581–609, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pastukh V, Ricci V, Solodushko V, Mozaffari M, Schaffer SW. Contribution of the PI 3-kinase/Akt survival pathway toward osmotic preconditioning. Mol Cell Biochem 269: 59–67, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastukh V, Shokolenko IN, Wilson GL, Alexeyev MF. Mutations in the passenger polypeptide can affect its partitioning between mitochondria and cytoplasm: mutations can impair the mitochondrial import of DsRed. Mol Biol Rep 35: 215–223, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastukh V, Wu S, Ricci C, Mozaffari M, Schaffer S. Reversal of hyperglycemic preconditioning by angiotensin II: role of calcium transport. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1965–H1975, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penna C, Mancardi D, Rastaldo R, Pagliaro P. Cardioprotection: a radical view; free radicals in pre and postconditioning. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787: 781–793, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage activated T-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev 83: 117–161, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piper HM, Garcia-Dorado D, Ovize M. A fresh look at reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 38: 291–300, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricci C, Jong CJ, Schaffer SW. Proapoptotic and antiapoptotic effects of hyperglycemia: role of insulin signaling. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 86: 166–172, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ricci C, Pastukh V, Leonard J, Turrens J, Wilson G, Schaffer D, Schaffer SW. Mitochondrial DNA damage triggers mitochondrial superoxide generation and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C413–C422, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigo GC, Samani NJ. Ischemic preconditioning of the whole heart confers protection on subsequently isolated ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H524–H531, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roux S, Buhler M, Clozel JP. Mechanism of the antiischemic effect of mibefradil, a selective T calcium channel blocker in dogs; comparison with amlodipine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 27: 132–139, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satoh H, Sugiyama S, Nomura N, Terada h Hayashi H. Importance of glycolytically derived ATP for Na+ loading via Na+/Na+ exchange during metabolic inhibition in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Clin Sci 101: 243–251, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaffer SW, Ballard Croft C, Solodushko V. Cardioprotective effect of chronic hyperglycemia: effect of hypoxia-induced apoptosis and necrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1948–H1954, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaffer SW, Solodushko V, Kakhniashvili D. Beneficial effect of taurine depletion on osmotic sodium and calcium loading during chemical hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C1113–C1120, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steenbergen C, Hill ML, Jennings RB. Volume regulation and plasma membrane injury in aerobic, anaerobic, and ischemic myocardium in vitro. Circ Res 57: 864–875, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tashiro M, Inoue H, Konishi M. Metabolic inhibition strongly inhibits Na+-dependent Mg2+ efflux in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J 96: 4941–4950, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhuang S, Hirai SI, Ohno S. Hyperosmolality induces activation of cPKC and nPKC, a requirement for ERK1/2 activation in NIH/3T3 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C102–C109, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]