Abstract

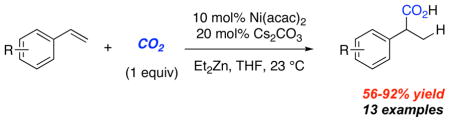

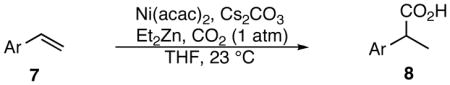

A nickel catalyzed reductive carboxylation of styrenes using CO2 has been developed. The reaction proceeds under mild conditions using diethylzinc as the reductant. Preliminary data suggests the mechanism involves two discrete nickel-mediated catalytic cycles, the first involving a catalyzed hydrozincation of the alkene followed by a second, slower nickel-catalyzed carboxylation of the in situ formed organozinc reagent. Importantly, the catalyst system is very robust and will fixate CO2 in good yield even if exposed to only an equimolar amount introduced into the headspace above the reaction.

Carbon dioxide is an extremely attractive carbon source that is readily available, inexpensive, and inherently renewable. Its utilization as a C1 feedstock in both large-scale fixation processes and small-scale synthesis has seen considerable growth in recent years.1 While transition metals promise a mild and efficient alternative for the incorporation of carbon dioxide into organic molecules, such methodology remains largely undeveloped.2 Current methods for catalyzed carbon-carbon bond formation using CO2 have been largely limited to reactions with extensive π systems (dienes and diynes)3,4 or in carboxylation of preformed organometallics.5 Herein we report a nickel-catalyzed reductive carboxylation of styrenes under an atmosphere of CO2.

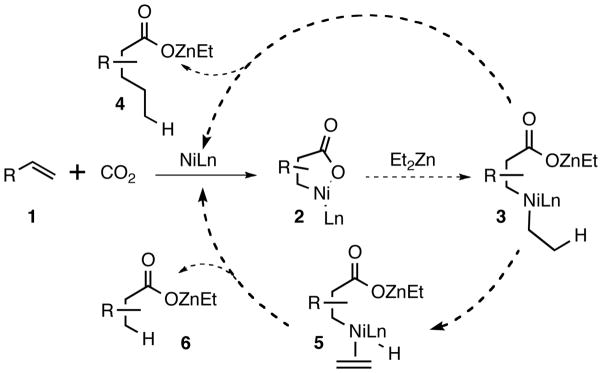

The nickel-mediated stoichiometric fixation of carbon dioxide with alkenes has been known for over 20 years largely due to the work of Hoberg.6 Inspired by this body of work, we have previously demonstrated that metalacycles such as 2, generated from cyclic anhydrides and nickel complexes, could be trapped with Ph2Zn as a nucleophile.7 We speculated that the use of Et2Zn could lead to either alkylative (4) or reductive (6) carboxylation of alkenes if conducted under a CO2 atmosphere (Scheme 1). Although eminently reasonable on paper, potential problems included balancing desired reactivity with the potential catalyzed direct addition of the alkylzinc reagent to CO2, as demonstrated recently by others.5f,5g We were confident, however, that judicious choice of ligand would lead to a favorable outcome.

Scheme 1.

Envisioned Reactivity

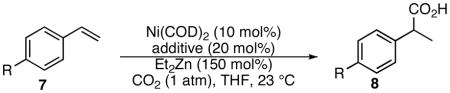

Initial attempts at the reductive carboxylation of activated styrenes began with electron deficient methyl-4-vinylbenzoate (7a). Much to our delight a ligand screen (Table 1, entry 3) revealed that the use of Ni(COD)2, DBU (1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene)6,4 and Et2Zn, under CO2 results in the formation of carboxylic acid 8a as a single regioisomer in 85% yield. Perhaps most importantly, this alpha-carboxylated product is generated under 1 atm of CO2 supplied by a balloon, avoiding specialized gas manipulation.

Table 1.

Initial ligand screen for reductive carboxylation

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | additive | yield (%) |

| 1 | CO2Me (a) | none | <5 |

| 2 | CO2Me (a) | bipy | NR |

| 3 | CO2Me (a) | DBU | 88 |

| 4 | CO2Me (a) | pyridine | 90 |

| 5 | CO2Me (a) | PPh3 | NR |

| 6 | H (b) | DBU | NR |

| 7 | H (b) | KHMDS | 35 |

| 8 | H (b) | Cs2CO3 | 56 |

While the reaction with activated styrene 7a is quite efficient, the use of styrene itself under identical conditions results in no carboxylated product (Table 1, entry 6).

In an effort to expand the utility of the reaction, a series of nitrogen and phosphorus ligands were examined with nearly uniform failure.8 The success of DBU as a ligand was difficult to rationalize but we speculated that it could be a function of its basicity rather than simply its donor character. That thought led us to investigate bases not typically considered ligands on late transition metals. Basic additives proved moderately successful (Table 1, entry 7), leading us toward examination of a series of inorganic bases as well. The use of Cs2CO3 as a ligand/additive affords 8b in 56% yield (entry 8), and with this result we began exploration of the scope.

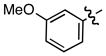

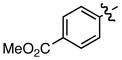

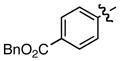

Hammett σm/p and σp+ values have proven useful in the prediction of reactivity.9 With few exceptions, electron deficient styrenes with positive σ values undergo reductive carboxylation very efficiently regardless of substitution pattern (Table 2, 8a, 13a, 14a), while those with negative σ values generally fail to produce the desired product. Furthermore, the reaction is tolerant of a variety of functional groups, including aryl chlorides, esters, ketones, and nitriles.

Table 2.

Reductive carboxylation substrate scope.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entrya | Aryl Group (Ar) | σm/p/σ+b | yield (%)c |

| 1 |

b b

|

0 | 56 |

| 2 |

c c

|

- | 60 |

| 3 |

|

- | 66 |

| 4 |

e e

|

0.12 | 92 |

| 5 |

f f

|

0.37 | 68 |

| 6 |

g g

|

- | 65 |

| 7 |

h h

|

0.43 | 79 |

| 8 |

a a

|

0.45/0.48 | 84 |

| 9 |

i i

|

0.45/0.48 | 81 |

| 10 |

j j

|

0.50/0.51 | 72 |

| 11 |

k k

|

0.54/0.61 | 92 |

| 12 |

l l

|

- | 87 |

| 13 |

m m

|

0.66/0.66 | 61 |

Standard conditions: Ni(acac)2 (10 mol%), CS2CO3 (20 mol%), Et2Zn (250 mol%), 18 h.

See reference 9.

isolated yield.

|

(1) |

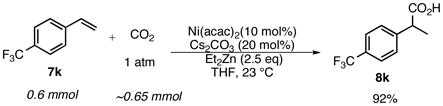

Although our screens involve 10 mol% nickel, we have shown that 1 mol% Ni(acac)2 works equally well.10 Typical reaction conditions utilize a balloon containing approximately 1 L of CO2 (45 mmol). To test consumption efficiency, a reaction was run in a 15 mL flask with only a headspace of CO2: roughly one equivalent of carbon dioxide relative to styrene 7k (eq 1). Complete consumption of styrene was observed and 92% of 8k was isolated indicating that the hydrocarboxylation reaction proceeds under CO2 pressure well below 1 atm.

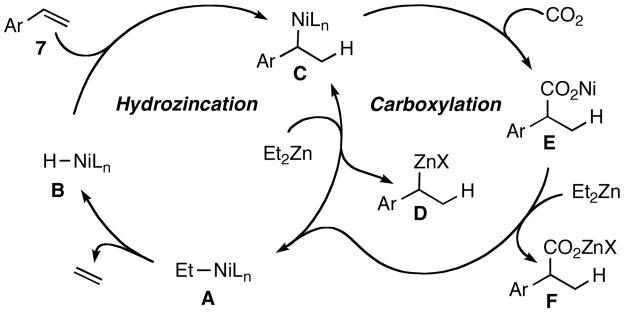

Although Hoberg’s work involving metalacycles provided the intellectual impetus for this research, initial investigations suggest a different mechanism may be operative, one proceeding through a nickel-hydride active catalyst (B, Scheme 2). Insertion of styrene into the nickel-hydride bond provides benzyl nickel species C; a transmetalation generates the benzylic zinc species D, the product of net hydrozincation of the alkene,11 while also regenerating Et-Ni complex A. Beta-hydride elimination and release of ethylene from A generates the presumed active catalyst B.12 A separate catalytic cycle involving transmetalation back to nickel (D to C) generates another benzylic nickel species which undergoes insertion of CO2 prior to transmetalation with Et2Zn, producing the hydrocarboxylation product F and regenerating precatalyst A. In support of this mechanism, we note that a D2O quench after 1 h provides significant amounts of the reduced alkene bearing a deuterium in the benzylic position, suggestive of the presence of D.13,14 Importantly, the direct addition of dialkylzinc reagent to CO2 5f,5g is extremely slow.15

Scheme 2.

Proposed reductive carboxylation mechanism

A catalyzed hydrocarboxylation has been developed for a variety of electron deficient and neutral ortho- meta- and para-styrene analogues.16 This reaction represents the foundation of a methodology to incorporate carbon dioxide in the preparation of more complex synthetic intermediates. Of additional interest is the efficient uptake of CO2, which occurs under only 1 atm of CO2. Studies to extend the reaction scope17 are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

JBJ thanks the NIH for a postdoctoral fellowship. TR thanks Lilly, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Johnson and Johnson for support, and the Monfort Family Foundation for a Monfort Professorship. We thank Professor Rick Finke for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, ligand screen and spectral data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a) Sakakura T, Choi JC, Yasuda H. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2365. doi: 10.1021/cr068357u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Louie J. Curr Org Chem. 2005;9:605. [Google Scholar]; c) Walther D. Coord Chem Rev. 1987;79:135. [Google Scholar]; d) Gibson DH. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2063. doi: 10.1021/cr940212c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Braunstein P, Matt D, Nobel D. Chem Rev. 1988;88:747. [Google Scholar]; b) Behr A. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1988;27:661. [Google Scholar]; c) Yin X, Moss JR. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;181:27. [Google Scholar]; d) Tsuda T. Gazz Chim Ital. 1995;125:101. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Takimoto M, Mori M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10008. doi: 10.1021/ja026620c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Takimoto M, Nakamura Y, Kimura K, Mori M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5956. doi: 10.1021/ja049506y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Louie J, Gibby JE, Farnworth MV, Tekavec TN. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15188. doi: 10.1021/ja027438e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Tekavec TN, Arif AM, Louie J. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7431. [Google Scholar]; e) Tsuda T, Morikawa S, Sumiya R, Saegusa T. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3140. [Google Scholar]; f) Takimoto M, Kawamura M, Mori M, Sato Y. Synlett. 2005:2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickel-mediated carboxylations: Takimoto M, Mori M. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2895. doi: 10.1021/ja004004f.Takimoto M, Mizuno T, Mori M, Sato Y. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7589.Aoki M, Kaneko M, Izumi S, Ukai K, Iwasawa N. Chem Commun. 2004:2568. doi: 10.1039/b411802b.

- 5.a) Shi M, Nicholas KM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5057. [Google Scholar]; b) Franks RJ, Nicholas KM. Organometalics. 2000;19:1458. [Google Scholar]; c) Ukai K, Aoki M, Takaya J, Iwasawa N. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8706. doi: 10.1021/ja061232m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Takaya J, Tadami S, Ukai K, Iwasawa N. Org Lett. 2008;10:2697. doi: 10.1021/ol800829q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Ohishi T, Nisiura M, Hou Z. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2008;47:5792. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Yeung CS, Dong VM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7826. doi: 10.1021/ja803435w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Ochiai H, Jang M, Hirano K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Org Lett. 2008;10:2681. doi: 10.1021/ol800764u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Eghbali N, Eddy J, Anastas PT. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6932. doi: 10.1021/jo801213m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Greco GE, Gleason BL, Lowery TA, Kier MJ, Hollander LB, Gibbs SA, Worthy AD. Org Lett. 2007;9:3817. doi: 10.1021/ol7017246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Hoberg H, Ballesteros A, Sigan A, Jegat C, Milchereit A. Synthesis. 1991:395. [Google Scholar]; b) Hoberg H, Gross S, Milchereit A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1987;26:571. [Google Scholar]; c) Hoberg H, Peres Y, Krüger C, Tsay YH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1987;26:271. [Google Scholar]; d) Hoberg H, Peres Y, Milchereit A. J Organomet Chem. 1986;307:C38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) O’Brien EM, Bercot EA, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10498. doi: 10.1021/ja036290b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Johnson JB, Rovis T. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:327. doi: 10.1021/ar700176t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.See Supplementary Information.

- 9.Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. Chem Rev. 1991;91:165. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reaction of 7k (0.6 mmol) provides 8k in 89% yield. This also demonstrates Cs2CO3 does not provide appreciable amounts of CO2.

- 11.a) Vettel S, Vaupel A, Knochel P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:1023. [Google Scholar]; b) Klement I, Lütjens H, Knochel P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:3161. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The use of other reductants (i-PrOH, Ph3SiH, H2) provides <10% yield. Me2Zn does not provide alkylated product; Ph2Zn affords benzoic acid.

- 13.Substrate 7c provides >50% ethylnaphthalene with ~10% 8c when quenched after 1 h.

- 14.Heterogeneous catalysis remains a consideration, although a preliminary mercury drop experiment does not support it. See: Widegren JA, Finke RG. J Mol Catal A. 2003;198:317.

- 15.A preformed naphthyl methylzinc reagent does not undergo carboxylation in the absence of nickel (18 h, THF, 23 °C, 1 atm CO2).

- 16.For hydroacylation of styrenes using anhydrides and H2, see: Hong YT, Barchuk A, Krische MJ. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2006;128:6885. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602377.

- 17.Under these conditions, cyclohexadiene, decene and β-methylstyrene give <10% yield of expected product.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.