Abstract

Purposes

Non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is characterized by accumulation of macular drusen, changes in pigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium, and geographic atrophy. The purposes of this study were to (1) measure the rate of progression of non-neovascular AMD and (2) from the rate data, to propose patient selection criteria for testing drugs to prevent progression of non-neovascular AMD.

Methods

Medical charts were searched for all AMD billing codes, consecutively reviewed, and 51 patients with a median age of 76 years were mined for severity of AMD using a standardized worsening scale from 0 to 6, visual acuity (VA, Snellen), medications or procedures to treat eye diseases, date of eye examinations, age, and sex. Individual eyes, excluding those with cataract, were grouped and compared.

Results

Using all grades, VA (logMAR) was positively correlated with AMD scores (P < 0.0001, n = 66). The median length of time to progress from AMD grade 3 or 4 to the next grade was 1.0 (n = 14) and 1.7 years (n = 7), respectively. Statistical analyses predicted that drug-treated and nontreated groups, each containing 409 grade 3 and 4 AMD eyes, could detect 50% drug inhibition (P = 0.05) in a 2-year trial.

Conclusions

VA measurements and structural AMD grades would be useful markers in clinical trials on non-neovascular AMD. Recruiting only grade 3 and 4 patients may be ideal for time- and cost-efficient pilot drug efficacy studies on moderately progressing non-neovascular AMD.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of vision loss in the elderly.1 Early non-neovascular AMD is characterized by accumulation of macular drusen and changes in pigmentation, whereas late AMD progresses to geographic atrophy, neovascularization, and severe loss of central vision.2 Cigarette smoking, heredity, and older age are consistent risk factors for development of AMD.3

The exact biochemical mechanism underlying AMD is unknown, but several hypotheses have been proposed. These include oxidative stress injury to the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choriocapillaris, chronic inflammatory responses in Bruch's membrane and choroid, formation of abnormal extracellular matrix, and altered diffusion of nutrients to the retina and RPE.4 Further, studies in cultured cells suggest that retinal ischemia and altered membrane permeability lead to influx of calcium and activation of cell death mechanisms related to activation of caspases and calpain proteases.5–7 Calpain substrates include rhodopsin, vimentin, and α-spectrin; and calpain inhibitors such as SNJ-1945 have ameliorated several animal and cell models of other types of retinal diseases.8

No generally accepted or effective treatment exists for non-neovascular AMD. Thermal laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, vitreoretinal surgery, and antiangiogenic drugs (such as anti-vascular endothelial growth factor molecules) have been tested against the most advanced form of AMD, exudative or choroidal neovascular AMD, where the most severe loss of visual acuity (VA) occurs.1 Fortunately, this “wet” AMD occurs in only 10% to 20% of patients with AMD. Dietary antioxidant supplementation reduced the risk of severe vision loss in intermediate forms of non-neovascular AMD and severe AMD, but it produced no conclusive effect on primary prevention of early AMD.3,9 Prevention or reduction in the rate of progression of the less severe stages of the more common non-neovascular AMD would be of tremendous benefit for patient quality of life as well in reducing medical costs. Moreover, early rescue of RPE and/or photoreceptor cells by a drug treatment would probably delay progression of non-neovascular AMD. The progression of AMD is generally fairly slow. For example, the massive AREDS study with 3,640 patients found a rate of 4% per year for progression from early to late stage AMD.9 For practical reasons, being able to minimize the number of patients entered into pilot clinical drug trials and to follow them over a reasonable time period (∼ 3 years) would be desirable. Thus, the purposes of the present study were to (1) measure the rate of progression of non-neovascular AMD by data mining from a limited number of patient charts and (2) from the rate data, to propose patient selection criteria for pilot testing of drugs to prevent progression of non-neovascular AMD.

Methods

Protocol

De-identified data were retrieved from the medical charts of patients at the Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health and Science University, according to a protocol approved by our Institutional Review Board and conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2008). The medical charts were first searched for all AMD billing codes and consecutively reviewed. Ophthalmic technicians then assigned each eye a grade for AMD, ranging from 1 to 6 using defined, written criteria (Fig. 1). Note that drusen were used as the primary indicator for grading early macular degeneration in this study; significant hyper- and hypopigmentation tended to occur later in the disease at stage 4. Assigned grades were reviewed for consistency by the same attending ophthalmologist. Other data obtained from the charts were best corrected Snellen VA10 with some excluded due to cataract bias (Table 1), medications, or procedures to ameliorate eye diseases, date of each eye examination, sex, and age. Although suspected to influence the development of non-neovascular AMD, tobacco use, nutrient intake, and family history were not collected in this study, because such data were inconsistently recorded in the charts accessed.

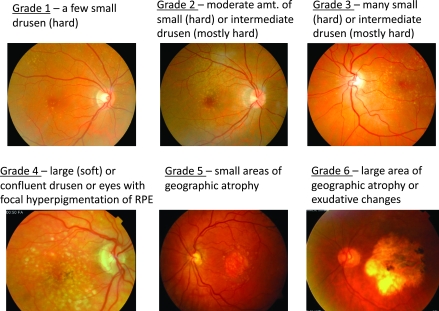

FIG. 1.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) scale used in the present study with representative fundus photographs and observational definitions of grades 1–6. A zero (0) score was assigned to eyes with no observable AMD pathology (not shown).

Table 1.

Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration Subjects (51 Patients and 100 Eyes)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at first diagnosis (years) | |

| Median with range (lowest, highest) | 76 (57, 86) |

| No age data | 8 patients |

| Sex (n) | |

| Male | 19 (37%) |

| Female | 32 (63%) |

| Ethnicity (n) | |

| Caucasian | 40 (78%) |

| Asian | 2 (4%) |

| No data | 9 (18%) |

| Observation period (first diagnosed to latest exam) (years) | |

| Median with range (shortest, longest) | 5.8 (1.5, 12.0) |

| VA excluded/included due to presence/absence of cataract (no. of eyes) | |

| All VA exams used because cataract never present in the eye | 27 (27%) |

| Only exams after cataract surgery | 37 (37%) |

| Only exams before development of cataract | 4 (4%) |

| Only exams before development of cataract and after cataract surgery | 2 (2%) |

| No VA data used, cataract always present | 30 (30%) |

Two eyes from 2 patients were excluded, because the AMD scores were 0 until the final exam.

Abbreviations: AMD, age-related macular degeneration; VA, visual acuity.

Data analysis

The AMD grades in individual eyes from the same patient were different 31% of the time, and each eye was, thus, treated as an independent observation. VA from Snellen chart data was converted to logMAR and correlated to AMD scores using Spearman's rank correlation. Data were grouped based on AMD grades, and the progression of AMD over the observation periods was calculated using JMP Statistical Software, version 8.0.1 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 51 patient charts containing a diagnosis of AMD in at least 1 eye were reviewed in detail, selected from patients who had been followed in our academic, comprehensive eye clinic serving patients mainly from the Northwest United States. The patients had been seen in the clinic for 1.5 to 12 years with a median retrospective observation period of 5.8 years (Table 1). Patient characteristics showed a median age of 76 years when AMD was first diagnosed, ∼2:1 ratio of female to male patients, and predominantly Caucasian ethnicity.

Initial prevalence of AMD

At the first eye exam, 20 eyes were initially scored 0 (normal), whereas the most prevalent AMD grades were mild to moderate grade 1 (38 eyes), grade 2 (21 eyes), and grade 3 (8 eyes) (Fig. 2). Relatively few eyes were scored in the more severe grade 4 (3 eyes), grade 5 (4 eyes), and grade 6 (6 eyes) at the first exam.

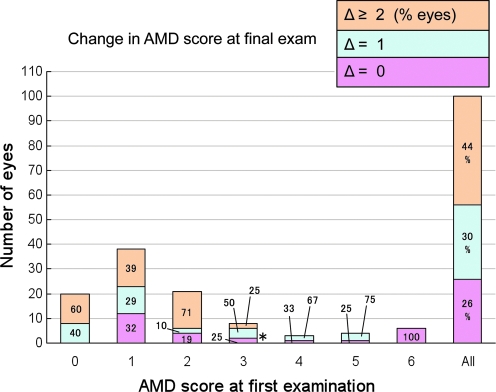

FIG. 2.

Total changes in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) grades occurring during the entire data collection period of this study. One hundred eyes were grouped according to their AMD grade at their first examination (x-axis), with the resulting number of eyes categorized into each group shown on the y-axis. Overall changes in AMD grades after the final recorded eye examination are shown in the bars as pink (no change), blue (1 grade higher), or orange (≥2 grades higher). The % within each segment of the bar indicates the proportion of eyes within a group showing a specified change. For example (*), of 8 eyes with initial AMD grade of 3, 50% (4 eyes) progressed 1 grade to AMD 4 over the entire observation period.

Progression of AMD

In all eyes with AMD scores 0–6, 30% increased 1 AMD grade, and 44% increased 2 or more AMD grades during the variable intervals between their first and last recorded eye examinations (Fig. 2, “All”). Only 26% of the eyes showed no progression of AMD.

Note that mild grade 1 and 2 eyes showed higher percentages with 2 or more grade changes, whereas grade 4 showed a higher percent with only 1 grade change (Fig. 2). Moderately severe grade 3 showed 50% of eyes with 1 grade change. Of course, all eyes showing no change were those with the terminal, most severe grade AMD 6 at their first clinic visit.

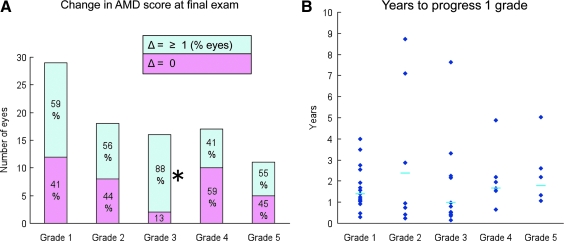

Stabilization of AMD

Pathology in some eyes suggested nonconstant progression. This was evident in eyes with grades 2 and 4 at the initial or intermediate exams, where 44% and 59%, respectively, of the eyes showed no further change in AMD grade (Fig. 3A). In contrast, 88% of the eyes scoring 3 at initial or intermediate exams showed 1 or more AMD grade changes (Fig. 3A). The median length of time to progress from grade 2, 3 or 4 to the next grade was 2.4 (n = 10), 1.0 (n = 14), and 1.7 years (n = 7), respectively (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

(A) Progressive nature of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) grades. Eyes attaining a 1–5 grade at initial or intermediate exams were grouped (x-axis), with the resulting number of eyes shown on the y-axis. By the final exam, changes in AMD are indicated by colors within the bars, as pink (no change) or blue (Δ ≥ 1 AMD score) and as % of total eyes. For example (*), 88% of 16 total eyes progressed from grade 3 to grade 4 or higher. (B) Distribution of the time (years, y-axis) for individual eyes (blue diamonds) to progress 1 grade, with median times shown as blue bars. In eyes where the AMD score increased >1 grade, the data were extrapolated back to the length of time predicted for an increase of 1 grade only.

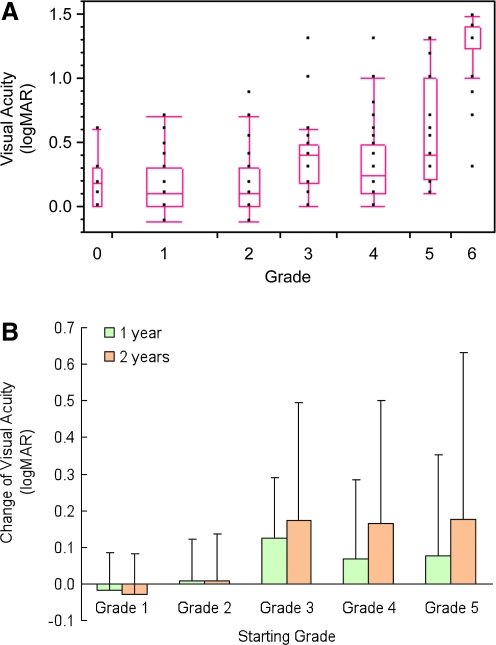

Correlation of pathology with VA

Compared with normal eyes (grade 0), eyes with AMD grades ≤2 did not show major decreases in VA, whereas those with AMD grades >2 showed loss of VA (Fig. 4A). We found a statistically significant positive correlation between increasing AMD scores and decreased VA (Fig. 4A), calculated using all graded eyes and removing confounding VA data due to cataracts. In grades 3 and 4, eye examinations 1 and 2 years later showed major degradation of VA (Fig. 4B). This was not observed in grade 2 eyes.

FIG. 4.

(A) Box and whisker plot for correlation between increasing age-related macular degeneration (AMD) score (x-axis) and decreasing visual acuity (VA) (y-axis). Each point represents an individual eye. The top and bottom lines of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, middle lines in the boxes represent the medians, and the upper and lower ends of the whiskers are at the upper and lower quartiles ± 1.5 × interquartile range, showing outlier data points and indicating a lack of normal distribution of data with advancing AMD. Nonparametric Spearman's coefficient of rank correlation (ρ) between AMD and VA was 0.57 (P < 0.0001, n = 66 using all data points). (B) Degradation of VA (y-axis) occurring in groups of eyes scoring 1–5 (x-axis) after re-testing 1 year (green bars) and 2 years (orange bars) later. At 2 years, changes in logMAR for grades 3 and 4 were 0.17 ± 0.32 (14) (equivalent to loss of ∼8.5 letters on the ETDRS chart) and 0.16 ± 0.34 (11) units, respectively.

Discussion

The major conclusion from this base-line study was that patients with at least 1 eye graded AMD 3 or 4 would be ideal for pilot, inhibitory drug efficacy studies.

Several pieces of data supported the conclusion above. (1) The pathology in grades 3 and 4 was moderate to intermediate with drusen, but without atrophy (Fig. 1). Soft drusen, characteristic of grade 4 eyes, are usual precursors of advanced AMD.11 This means that a drug may be able to intervene before the atrophy characteristic of more severe grades 5 and 6 occurs in the macula. (2) A larger percentage (75%–88%) of grade 3 eyes were likely to show significant progression of AMD, compared with slower progression in eyes with grades 1, 2, and 5 (Figs. 2 and 3A). The slower progression of earlier stages of AMD has been previously noted and could have been responsible for the lack of beneficial effect of dietary antioxidants on early AMD in the 6 year AREDS study.9 (3) In our study, the progression of grade 3 eyes to grade 4 or progression of grade 4 eyes to grade 5 occurred in a fairly short time frame of approximately 1–2 years (Fig. 3B). These observations suggested that grade 3 and 4 patients could be treated with a drug against an active, but not overwhelmingly progressive, disease in a practical time period for a pilot study.

Loss of VA appeared first graphically noticeable in Fig. 4 in grade 3 patients. Further, the statistically significant correlation between AMD severity and decreased VA over all grades was important, because the ultimate goal of drug intervention studies is to preserve VA. VA is also easier to measure in the field without the need for more expensive slit lamp biomicroscopy or optical coherence tomography at each exam.

Finally, the VA data allowed a rough prediction of how many grade 3 and 4 eyes would be needed in a non-neovascular AMD drug trial. For example, we used the observed degradation of VA for grades 3 and 4 at 2 years (Fig. 4B), and we assumed a 50% reduction in the loss of VA in a drug-treated group compared with the vehicle-only group. Student's t-test predicted the need for 409 grade 3 and 4 eyes in each group to detect a statistically significant difference (P = 0.05) in a 2-year trial. Longer trial periods would probably lower the number of eyes needed. For such an initial trial, patients with grade 2 eyes would be excluded, as the degradation of VA was low (Fig. 4B) and might extend the time required for pilot studies. Of course, the limitations of these calculations are that they are based on a relatively small number of patients, use of each eye from the same patient as a separate data point, and lack of control for relevant patient variables (e.g., cigarette smoking). However, the data do provide practical guidelines derived from readily accessible, retrospective data mining. The guidelines indicated that pilot studies on drugs for treating non-neovascular AMD are feasible within a practical time period (∼3 years) with a reasonable total number of AMD eyes.

An example of the significance and use of the above criteria would be to test our hypothesis that calpain inhibitors could be used to slow the progression of AMD. Calpains are calcium-activated cysteine proteases found in nearly all tissues including retina.8 We speculate that Ca2+ influx due to age-related oxidation at the blood-retinal barrier (retinal epithelial cells) and ischemia from degeneration of the choriocapillaris may activate calpains causing proteolysis of retinal proteins, photoreceptor cell death, and macular degeneration. More than 50 calpain inhibitors are known, and we hope to test a 3rd generation inhibitor (SNJ-1945) that has improved membrane permeability and calpain specificity against AMD using the patient selection criteria proposed in the present study.

Author Disclosure Statement

Drs. Shearer and Chung have significant financial interests (research contract and/or consulting fee) in Senju Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Dr. Azuma and Ms. Fujii are employees of Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., a company that may have commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. These potential conflicts of interest have been reviewed and managed by the OHSU Conflict of Interest in Research Committee.

References

- 1.Gehrs K.M. Anderson D.H. Johnson L.V. Hageman G.S. Age-related macular degeneration—emerging pathogenetic and therapeutic concepts. Ann, Med. 2006;38:50–71. doi: 10.1080/07853890600946724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird A.C. Bressler N.M. Bressler S.B., et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. The International ARM Epidemiological Study Group. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1995;39:367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80092-x. [Review]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong E.W.-T. Wong T.Y. Kreis A.J. Simpson J.A. Guymer R.H. Dietary antioxidants and primary prevention of age related macular degeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39350.500428.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stokkermans T.J. What's new in clinical trials for treatment of dry AMD. Fifth Annual Guide to Retinal Diseases. Suppl. to Review of Optometry. Nov, 2008. www.revoptom.com www.revoptom.com

- 5.Tamada Y. Walkup R.D. Shearer T.R. Azuma M. Contribution of calpain to cellular damage in human retinal pigment epithelial cells cultured with zinc chelator. Curr. Eye Res. 2007;32:565–573. doi: 10.1080/02713680701359633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma H. Tochigi A. Shearer T.R. Azuma M. Calpain inhibitor SNJ-1945 attenuates events prior to angiogenesis in cultured human retinal endothelial cells. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;25:409–414. doi: 10.1089/jop.2009.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanan Y. Moiseyev G. Agarwal N. Ma J.X. Al-Ubaidi M.R. Light induces programmed cell death by activating multiple independent proteases in a cone photoreceptor cell line. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:40–51. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azuma M. Shearer T.R. The role of calcium-activated protease calpain in experimental retinal pathology. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2008;53:150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.12.006. [Review]. Erratum in: Surv. Ophthalmol. 53:308–310, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS Report No. 8. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Csaky K.G. Richman E.A. Ferris F.L., 3rd Report from the NEI/FDA ophthalmic clinical trial design and endpoints symposium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49:479–489. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnusson K.P. Duan S. Sigurdsson H., et al. CFH Y402H confers similar risk of soft drusen and both forms of advanced AMD. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]