Doty et al. in this technical report generate and characterize a helper-free, packaging system composed entirely of feline leukemia virus subgroup C (FeLV-C) components. Using this new packaging system, the authors demonstrate that they can produce higher titer vectors than existing gammaretroviral packaging systems.

Abstract

The subgroup C feline leukemia virus (FeLV-C) receptor FLVCR is a widely expressed 12-transmembrane domain transporter that exports cytoplasmic heme and is a promising target for retrovirus-mediated gene delivery. Previous studies demonstrated that FeLV-C pseudotype vectors were more efficient at targeting human hematopoietic stem cells than those pseudotyped with gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV), and thus we developed an all FeLV-C-based packaging system, termed CatPac. CatPac is helper-virus free and can produce higher titer vectors than existing gammaretroviral packaging systems, including systems mixing Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) Gag-Pol and FeLV-C Env proteins. The vectors can be readily concentrated (>30-fold), refrozen (three to five times), and held on ice (>2 days) with little loss of titer. Furthermore, we demonstrate that CatPac pseudotype vectors efficiently target early CD34+CD38– stem/progenitor cells, monocytic and erythroid progenitors, activated T cells, mature macrophages, and cancer cell lines, suggesting utility for human cell and cell line transduction and possibly gene therapy.

Introduction

The most common gammaretrovirus-based gene therapy vectors are pseudotyped with amphotropic, gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV), vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G (VSV-G), or feline endogenous virus RD114 envelope (Env) proteins. The amphotropic and GALV Env proteins target the phosphate transporters Pit2 and Pit1, respectively, whereas RD114 targets the related amino acid transporters SLC1A4 and SLC1A5 as receptors (Kavanaugh et al., 1994; Rasko et al., 1999; Tailor et al., 1999a). The feline leukemia virus subgroup C (FeLV-C) uses the heme transporter FLVCR as a receptor (Tailor et al., 1999b; Quigley et al., 2000, 2004), thus providing an alternative receptor for delivery of gene therapy vectors.

GALV pseudotype vectors generally result in higher transduction rates in CD34+ cells than do amphotropic pseudotype vectors under similar transduction conditions, and this difference is reflected in the level of mRNA for each viral receptor in the target cell population (Orlic et al., 1996; Sabatino et al., 1997). The receptors for GALV and RD114 virus are relatively low in concentration on human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSCs; lin–CD34+CD38–) and increase during differentiation, resulting in preferential transduction of more mature cells, whereas the expression of FLVCR, the FeLV-C receptor, is more highly concentrated on these immature cells (Lucas et al., 2005). This suggests that an FeLV-C-based packaging system may be more effective in targeting vectors to the more primitive cells. In support of this, FeLV-C pseudotype vectors were more effective in transducing HSCs than GALV pseudotype vectors in the sheep model system, in which unselected transduced human HSCs are transplanted into fetal sheep in utero (Lucas et al., 2005). Although the expression pattern of the receptors likely plays a key role in explaining the effectiveness of the FeLV-C-derived vectors, the structure or stability of the virion may also affect targeting efficiency. This raises the question of whether entirely FeLV-based viral particles might enhance the ability of the FeLV-C pseudotype vectors to target stem cells compared with hybrid vectors that contain Gag and Pol from Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) and Env from GALV. In this report, we have developed an all FeLV-C-based packaging system using FeLV 61E gag-pol (Overbaugh et al., 1988; Burns et al., 1996), FeLV-C (Riedel et al., 1986), and the human embryonic kidney line 293 (Graham et al., 1977).

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and retroviral vectors

The ψ-deleted FeLV-A LTR-Gag-Pol expression vector carrying a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven Zeocin resistance gene, pCZLGP, was kindly provided by J. Overbaugh (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). The FeLV-C envelope expression vector, pCSI-EFSC, uses a CMV promoter and a simian virus 40 (SV40) intron to drive expression of the envelope from the FeLV-C clone FSC (Riedel et al., 1986). pCMV-hygro (CMVhph) was described previously (Quigley et al., 2000). Additional vectors tested were the MoMLV ψ-deleted LTR-Gag-Pol vector pLGPS (Miller et al., 1991), and a ψ-deleted FeLV-C virus 61EC, originally termed 61EΔΨ-Cenv (Quigley et al., 2000). pMCIG was constructed by inserting the FeLV-C envelope into the upstream cloning site of pMXIG (a gift from D. Persons [St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN]; Persons et al., 1999). The murine stem cell virus (MSCV)-based marker vectors pMSCV-neo, pMSCV-hygro, pLGFP (pLIB containing EGFP) (all from Clontech, Mountain View, CA), pMXIG (Persons et al., 1999), and pMGIN (Cheng et al., 1997) were used throughout as described.

Reagents, cytokines, and antibodies

Zeocin and hygromycin B (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used at 400 μg/ml for selection and at 100 μg/ml for maintenance until clonal cell stocks were expanded and frozen. For stable transfections, cells were transfected with 10 μg of each linearized vector according to the instructions included with the CalPhos transfection kit (Clontech). After 24 hr, transfected cells were plated via limiting dilution and stable clones were isolated after 10 days in selection. To screen the clones for FeLV Gag-Pol expression, we used a p27gag ELISA kit (Leukassay; Pitman-Moore, Washington Crossing, NJ) as described previously (Abkowitz, 1991). The cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, stem cell factor (SCF), IL-3, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-SCF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and erythropoietin (a gift from Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) were used as described. Antibodies to CD3 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) and to CD11b, CD14, CD163, and glycophorin A (BD Biosystems, San Jose, CA) were used according to the manufacturers' recommended protocols. FLVCR staining was performed as described (Quigley et al., 2004).

Cells, cell lines, and culture media

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (Graham et al., 1977), feline embryonic fibroblast FEA cells (Jarrett et al., 1973), Phoenix-Ampho (a gift from G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA), Phoenix-GALV (a gift from H.-P. Kiem, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Horn et al., 2002), NRK/FLVCR (Quigley et al., 2004), HT-1080, HeLa, 293T, HepG2, Caco2, and NIH 3T3 (all from the American Type Culture Collection [ATCC, Manassas, VA]) cell lines were cultured in HEPES-buffered high-glucose (4.5 g/liter) Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen), 10 or 20% (Caco2) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), supplemented with nonessential amino acids, l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, penicillin, and streptomycin (Invitrogen). Frozen human peripheral blood CD34+ cells were obtained from S. Heimfeld (Hematopoietic Cell Processing Core, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) and human bone marrow and peripheral blood were collected from healthy donors after informed consent had been obtained, according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles and University of Washington IRB protocols 07-8016-N, 27340, and 29708. Frozen CD34+ cells were thawed and cultured in CCM (Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium [IMDM], 20% FBS, 1% bovine serum albumin [BSA] [Biocell Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA], penicillin, streptomycin, and Fungizone [Invitrogen]) supplemented with SCF (100 ng/ml), IL-3 (30 ng/ml), and IL-6 (50 ng/ml) for 48 hr before use as described (Quigley et al., 2004). Differentiation of erythroid, granulocyte, and monocyte progenitor cells was induced with SCF (100 ng/ml) and erythropoietin (2 U/ml); SCF (100 ng/ml), IL-3 (2 ng/ml), IL-6 (20 ng/ml), GM-CSF (10 ng/ml), and G-CSF (20 ng/ml); and SCF (100 ng/ml), IL-3 (20 ng/ml), and IL-6 (50 ng/ml), respectively. Mononuclear cells were isolated from marrow and blood with lymphocyte separation medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) as described (Abkowitz et al., 1998). Marrow-derived monocytes/macrophages were subsequently isolated by plastic adherence for 18 hr in X-VIVO 10 culture medium (Cambrex Bio Science, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 20% FBS, 1% BSA, M-CSF (10 ng/ml), penicillin, streptomycin, and Fungizone. Peripheral blood T cells were activated as described (Abad et al., 2002) in RPMI 1640 culture medium (Mediatech) with 10% FBS on immobilized anti-CD3 for 72 hr before transduction.

Vector production and quantitation

To produce retroviral vectors, 4.2 × 106 packaging cells were seeded in 10-cm tissue culture dishes the day before transfection. A total of 18 μg of DNA was used for each transfection (as described previously). After 18 hr, the transfection medium was replaced with fresh medium and supernatant collection began 24 hr later (collection day 1). Supernatants were clarified by centrifugation for 5 min at 400 × g and filtered (pore size, 0.22 μm), and then rapidly frozen in a dry ice–isopropanol bath or liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. The different freezing methods did not have any appreciably different effect on titers. For concentration of supernatants, the clarified supernatants were held at 4°C up to 72 hr and then concentrated by centrifugation (4000 × g for 18 hr). Vector pellets were resuspended in fresh medium, aliquoted, and frozen as described previously. Frozen supernatants were rapidly thawed at 37°C and immediately placed on ice until use. Modifications of these methods required for specific experiments are described in text.

Cell lines used for titering vectors were plated at optimal densities (empirically determined) in a 12-well plate for each line (FEA, 105; HT-1080, 2 × 105; HeLa, 105; 293, 2 × 105; HepG2, 2 × 105; Caco2, 105 cells per well) 24 hr before vector exposure. Fresh medium containing Polybrene (8 μg/ml) and vector in several amounts (0.3 to 0.0001 ml) was added to the cells, which were then incubated for 18 hr. For flow cytometry-based assays, the vector-containing medium was then replaced with fresh medium and the cells were cultured for an additional 2–4 days before analysis. Titers, expressed as transducing units per milliliter (TU/ml), were calculated by multiplying the number of cells present at the start of the transduction by the frequency of positive cells at analysis and dividing by the volume (ml) of virus used for transduction. For selection-based assays, the transduced cells were expanded into larger dishes containing G418 (750 μg/ml; Invitrogen) and cultured for 7–10 days before analysis as described (Josephson et al., 2000).

Functional screening for FeLV Gag-Pol and FeLV Cenv expression

293 cells were transfected with the FeLV Gag-Pol construct pCZLGP, and Zeocin-resistant clones were isolated and evaluated for Gag expression by FeLV p27 ELISA. We identified 10 clones expressing high amounts of Gag-Pol and then transiently transfected replicate clones with FeLV-C env and GFP, using the combined vector pMCIG. We screened the resulting supernatant titers on FEA cells to identify clones producing the highest titer supernatants. The two Gag-Pol clones (clones 40 and 84) resulting in the highest transduction frequency were subsequently cotransfected with linearized pCSI-EFSC and pCMV-hygro, selected, cloned, and then screened for production of high-titer vectors. Vector titers from five of these packaging clones were analyzed on FEA and HT-1080 cells to identify the two clones (CatPac6 and CatPac7) that consistently produced the highest titer vectors for these studies. CatPac cells can package MoMLV vectors and all vectors used in this study contain murine retroviral packaging signals.

Helper virus assay

Marker rescue studies were performed essentially as described (Miller and Buttimore, 1986) with the modification that we used FEA cells because mouse NIH 3T3 cells are not infectable with FeLV-C. Briefly, FEA-neo cells were cultured overnight with Polybrene (8 μg/ml) and 1 ml of supernatant from CatPac6, CatPac7, mock, or diluted FeLV-A stock (positive control). The culture was repeated the next day with fresh supernatants and Polybrene, and then the cells were washed and cultured for one more day. These cells were then cocultured with Polybrene (8 μg/ml) and FEA-hygro cells for 3 days and then expanded and selected with G418 (800 μg/ml) and hygromycin B (400 μg/ml) and analyzed as described previously. An alternative helper virus test was also performed by using supernatants from test cell lines (FEA-neo cells generated with CatPac or FEA-neo control cells infected with FeLV-A) to transduce FEA cells. These cells were selected with G418 and then conditioned supernatants were analyzed for the presence of retroviral vectors as described previously.

Primary CD34+ cell, macrophage, and T cell transduction

Transduction of CD34+ cells was adapted from Dybing and colleagues (1997). Briefly, RetroNectin-coated dishes were loaded twice with vector-containing medium and then CD34+ cells were resuspended with vector in CCM with SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and protamine (8 μg/ml) and immediately added to the prepared dishes and cultured for 6 hr. Cells were washed and then plated back into the same dishes with fresh medium and cytokines for 18 hr and then the vector exposure was repeated once. After the second vector exposure, cells were cultured for 2–7 days either in CCM with cytokines as before, or with the differentiation medium described previously. Erythroid progenitor cells were defined as glycophorin A+, granulocytes were defined as CD11b+CD14–, and monocytes were defined as CD14+. Bone marrow macrophages were transduced twice in a similar manner on RetroNectin-coated and vector-preloaded dishes in CCM with M-CSF (10 ng/ml). After transduction, macrophages were cultured in CCM/M-CSF for 5 days before analysis. Activated T cells were transduced twice in a similar manner on RetroNectin-coated and vector-preloaded dishes in RPMI 1640–10% FBS with Polybrene (8 μg/ml) and then cultured in RPMI 1640–10% FBS with IL-2 (5 ng/ml) for 5 days before analysis.

Results

Optimization of FeLV pseudotype retroviral vector titers

To identify an optimal combination of components to produce FeLV pseudotype retroviral vectors, we tested whether FeLV-C pseudotype vectors could be produced at higher titer with FeLV-C Gag, Pol, and Env proteins or with a mixture of MoMLV Gag and Pol and FeLV-C Env proteins. Vector production was measured after transient transfection of genes encoding these proteins into 293 cells. In five of five experiments that compared titers of vectors made with all FeLV proteins versus those made with MoMLV Gag and Pol and FeLV-C Env proteins, the vectors made with all FeLV proteins had the higher titers (average, 33-fold higher; range, 1.8- to 90-fold higher).

CatPac pseudotype vectors transduce cell lines with high efficiency

Clonal packaging cell lines were created, using separate expression plasmids containing the FeLV-C Gag-Pol coding region driven by the viral long terminal repeat (LTR) (pCZLGP) and the FeLV-C Env protein coding regions driven by the CMV promoter (pCSI-EFSC) as described in Materials and Methods. Of the five independent packaging clones analyzed, CatPac6 and CatPac7 produced the highest titers of a vector encoding GFP after transient transfection, when assayed with FEA or HT-1080 cells as targets for infection (data not shown).

In initial experiments, the vectors produced by the CatPac6 and CatPac7 packaging cells had similar titers that were routinely higher than those produced by Phoenix-GALV or Phoenix-Ampho packaging cells, suggesting that CatPac pseudotype vectors more efficiently transduce target cells (Table 1). The studies were internally controlled for transfection conditions, including simultaneous transfection from the same DNA transfection mix under the same culture conditions with comparable transfection levels (typically 85–90% GFP+). Vector titers measured on FEA cells were at least as high and often much higher (up to 50-fold higher) than those obtained with the human cell lines for all pseudotypes tested; amphotropic, GALV, and CatPac/FeLV-C. Both the GFP and neomycin resistance vectors used in these studies resulted in comparable titers and showed the same relative transduction rates (data not shown), which rules out the possibility of differential pseudo-transduction with GFP protein as the cause of the higher FEA titers.

Table 1.

Comparison of Vector Production after Transient Transfection of CatPac, 61EC, and Phoenix Packaging Cells

| |

Vector titer (104GFP+TU/ml) on target cells:a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging cells | FEA | HT-1080 | 293T | HeLa | HepG2 | Caco2 |

| CatPac6 | 140 ± 30 | 9.2 ± 5.2 | 38 ± 9 | 46 ± 25 | 99 ± 15 | 2.8 ± 0.8 |

| CatPac7 | 160 ± 30 | 15 ± 5 | 37 ± 14 | 26 ± 6 | 80 ± 13 | 4.0 ± 0.8 |

| Phoenix-Ampho | 18 ± 4 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 21 ± 4 | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| Phoenix-GALV | 15 ± 2 | 4.7 ± 1.8 | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 7.0 ± 3.8 | 13 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.0 |

| 61EC | 38 ± 13 | 7.0 ± 2.2 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 13 ± 8 | ND | ND |

Abbreviations: ND, not determined; TU, transducing unit.

Means ± SEM of five (FEA, HT-1080, 293T, and HeLa cells) or three (HepG2 and Caco2 cells) experiments.

We also evaluated transduction of human cell lines that are difficult to transfect: the Caco2 (small bowel phenotype) cell line and the HepG2 (hepatoma) cell line (Table 1). With HepG2 cells, all pseudotypes gave titers close to those obtained with FEA cells and titers of CatPac pseudotype vectors were 4- to 8-fold higher than those of amphotropic or GALV pseudotypes. All titers were substantially lower with the slow-growing Caco2 cells than observed with the other human cell lines, consistent with Caco2 being generally more difficult to transduce than other cell lines. The amphotropic-pseudotype vectors had the highest titers on Caco2, up to 25% higher than those obtained with CatPac pseudotype vectors in some experiments. The titers of CatPac pseudotype vectors on Caco2 were 2- to 3-fold higher than those of GALV pseudotype vectors.

In addition, we compared the titers of transiently produced CatPac pseudotype vectors with those produced by transient transfection with its components (pCZLGP and pCSI-EFSC) and with the ψ-deleted FeLV-C virus (61EC) used for the in utero sheep transplantation studies (Lucas et al., 2005). In both of these cases, the CatPac packaging lines produced higher titer vectors (Table 1 and data not shown).

In addition to developing the all FeLV-C-based packaging system in 293 cells (CatPac), we created a hybrid FeLV-C pseudotype packaging line in 3T3 cells, using the murine MoMLV Gag-Pol construct pLGPS (Miller et al., 1991) and the same FeLV-C Env construct (pCSI-EFSC). This hybrid system was the best 3T3-based FeLV-C pseudotype packaging system determined in preliminary studies (data not shown). Vector titers from three different hybrid 3T3-based clones were compared with identically produced CatPac vectors. The titers of the CatPac-produced vectors were 10- to 50-fold higher than those obtained with the hybrid 3T3-based system, which uses MoMLV Gag and Pol and FeLV-C Env proteins. Because of this major difference in packaging efficiency the hybrid 3T3-based system was not pursued further.

CatPac is helper virus free

We used two independent methods to determine whether either CatPac6 or CatPac7 had contaminating replication-competent retrovirus (RCR) created through recombination with endogenous sequences or the introduced retroviral components. CatPac supernatants did not contain any RCR (CatPac6, CatPac7, and mock: ≤0.7 CFU/ml; positive control, 6760 CFU/ml; n = 3) as detected by the marker rescue assay. When FEA cells were used in the marker rescue assay there was a very low level of dual-resistant (G418 and hygromycin) background colonies that grew without exposure to any viral supernatant. These background colonies grew only after coculture of the FEA-neo and FEA-hygro cells with Polybrene and may represent rare fusion events facilitated by Polybrene. As an independent assay for RCR we transduced FEA cells with CatPac-produced MSCVneo at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI) and selected for stable transductants. These FEA-neo cells did not contain any RCR, as conditioned supernatants from these transductants were not capable of transferring neomycin resistance to a secondary cell line (CatPac6 and CatPac7: <0.5 CFU/ml), whereas FEA-neo cells secreted high numbers of RCR (3.4 × 105 CFU/ml) after infection with FeLV-A.

CatPac-produced vectors are relatively stable

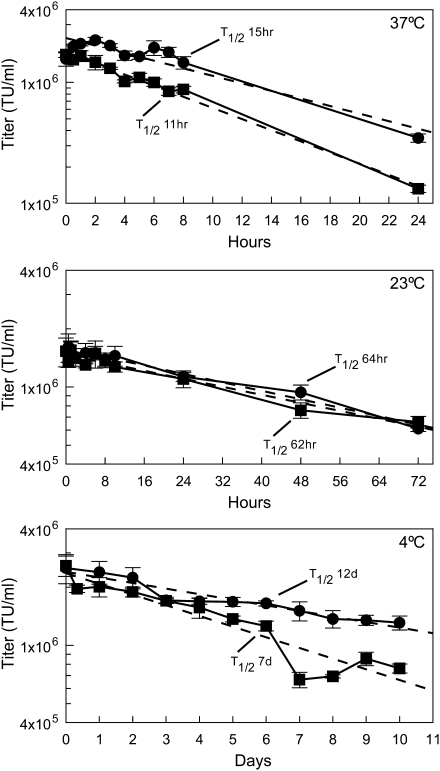

Although the ability to generate high-titer helper-free vector is essential for development of a packaging line, the stability of the virions is also important for it to be useful in producing vectors capable of undergoing the rigorous processes required to prepare clinical-grade vectors. The half-life of CatPac-produced vectors is between 11 and 15 hr (CatPac7 and CatPac6, respectively) at 37°C, 62–64 hr at 23°C, and 7 to 12 days at 4°C (Fig. 1). In addition, we found that long-term storage (4 years) of CatPac pseudotype vectors at −80°C resulted in no reduction in vector titers whereas 61EC pseudotype vector titers were reduced 25 to 70% during 4 to 7 years of storage.

FIG. 1.

CatPac pseudotype vector stability. Fresh conditioned medium from CatPac6 cells (solid circles) and CatPac7 cells (solid squares) transfected with pMGIN were held at 37°C, 23°C, or 4°C as indicated, and then rapidly frozen and stored at −80°C. Vector titers (GFP+ TU/ml) were measured, using FEA cells as targets. Linear regression (dashed) lines were calculated with DeltaGraph 5.6. Half-life was calculated from the linear regression formula and is indicated for each regression line. Data are presented as means ± SEM of triplicate samples, representative of three similar experiments.

The long half-life of CatPac-produced vectors held at 4°C provides the ability to hold supernatants from multiple collections, with negligible loss of activity, so they can be pooled for batch processing. To maximize the utility of this result, we tested how long transiently transfected CatPac packaging lines produce high-titer supernatant (Table 2). The titers peak 72 hr posttransfection (collection day 2), and continue at that level for approximately three more days (collection day 5); then the titer drops as much as 30% on collection day 6. This last drop in titer is likely caused by prolonged culture at confluency. We have not subcultured any of the transient producer lines in these studies to evaluate continued production of high-titer supernatants; however, lines selected as stable producer lines continue to produce high-titer supernatant as expected (data not shown).

Table 2.

CatPac Vector Production Stability

| |

Vector titer (106GFP+TU/ml)a |

Normalized to collection 1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection day | CatPac6b | CatPac7c | CatPac6 | CatPac7 |

| 1 | 1.57 ± 0.00 | 1.22 ± 0.19 | 100% | 100% |

| 2 | 2.06 ± 0.23 | 1.85 ± 0.35 | 132% | 151% |

| 3 | 1.75 ± 0.36 | 1.73 ± 0.10 | 111% | 141% |

| 4 | 1.51 ± 0.14 | 1.35 ± 0.14 | 97% | 110% |

| 5 | 1.71 ± 0.11 | 1.30 ± 0.17 | 109% | 107% |

| 6 | 1.44 ± 0.14 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 92% | 69% |

Abbreviation: TU, transducing unit.

Means ± SEM of titers on FEA cells for vector supernatants collected on six sequential days after transfection with the pMGIN reporter vector.

n = 4.

n = 5.

Freezing vector stocks for long-term storage is common; however, most vector stocks lose substantial activity with each freeze–thaw cycle (Kaptein et al., 1997) and are frequently discarded after one thaw. We tested CatPac-produced vector stocks for stability after multiple freeze–thaw cycles and found that these stocks are remarkably stable. CatPac6-derived stocks retained full activity after three freeze–thaw cycles (from 1.86 ± 0.26 × 106 to 1.92 ± 0.36 × 106 TU/ml, n = 3, representative of three independent experiments) and CatPac7-derived stocks lost 5–10% of their titer with each freeze–thaw cycle (from 1.85 ± 0.27 × 106 to 1.6 ± 0.2 × 106 TU/ml, n = 3, representative of three independent experiments), retaining more than 85% activity after three freeze–thaw cycles. Even after a total of six freeze–thaw cycles CatPac6- and CatPac7-produced vectors retained up to 80 and 70% activity, respectively.

CatPac-produced vectors are readily concentrated

In addition to the desired vector product, supernatants contain metabolites from the packaging line that can alter the phenotype and function of primary cells, and these metabolites are increasingly produced as cell density increases throughout the collection period. Thus successive collections are of limited use unless the medium can be replaced with fresh medium. Concentration of vectors via centrifugation has the added benefit of increasing titers, making storage and usage more facile. We performed small-scale concentrations with a 30-fold reduction in volume and determined the effect on the titers (Table 3). The average yield of functional vectors after concentration was approximately 40% of the starting material. Larger scale concentrations allowing more volume reduction (100-fold volume reduction) resulted in similar percentage recovery.

Table 3.

Efficient Concentration of CatPac Vectors

| |

Vector titer (106GFP+TU/ml)a |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconcentrated | Concentrated | Yield (%) | Range (%) | |

| CatPac6b | 1.47 ± 0.13 | 21.3 ± 3.1 | 37.7 ± 3.1 | 68–20 |

| CatPac7c | 1.31 ± 0.14 | 16.9 ± 2.1 | 44.1 ± 6.6 | 90–9 |

Abbreviation: TU, transducing unit.

Means ± SEM of titers for CatPac-produced vectors and efficiency of 30-fold concentration via centrifugation.

n = 16.

n = 17.

Primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells are efficiently transduced by CatPac vectors

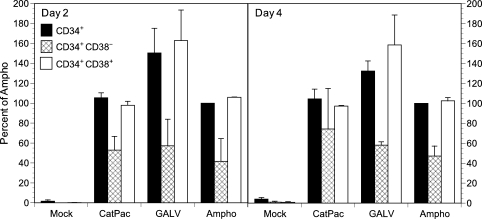

CD34+ hematopoietic cells are effectively targeted by FeLV-C pseudotype vectors, including HSCs capable of reconstituting hematopoiesis in fetal sheep (Lucas et al., 2005). We found that CatPac pseudotype vectors achieve maximal marking frequency of CD34+ cells at an MOI of 5, and therefore our comparisons were performed at an MOI of 5. Transduction of CD34+ cells with CatPac6, Phoenix-GALV, and Phoenix-Ampho pseudotype vectors resulted in average transduction frequencies of 20 ± 1.5% (CatPac, n = 6), 45 ± 8.6% (GALV, n = 4), and 22 ± 8.0% (Ampho, n = 4). To investigate why CatPac vectors marked fewer CD34+ cells when FeLV-C (61EC) pseudotype vectors were more efficient at targeting HSCs than GALV pseudotype vectors (Lucas et al., 2005), we examined the marking frequency in the more primitive CD34+CD38– subset (Fig. 2; and see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 at www.liebertonline.com/hum). The transduction frequency of total CD34+ cells analyzed 2 days posttransduction was comparable to previous experiments, with CatPac and amphotropic pseudotype vectors being comparable and lower than GALV pseudotype vectors. However, when we evaluated the transduction frequency of the more primitive CD34+CD38– cells, the marking frequency obtained with CatPac pseudotype vectors was comparable to that obtained with GALV and amphotropic pseudotype vectors at 2 days posttransduction and higher than that obtained with either GALV or amphotropic pseudotype vectors at 4 days posttransduction, indicating that CatPac pseudotype vectors transduce the more primitive CD34+CD38– cells as well as, or possibly better than, either GALV or amphotropic pseudotype vectors.

FIG. 2.

CD34+ progenitor cell transduction. CD34+ cells were transduced with Mock, CatPac6, GALV, or amphotropic pseudotype MGIN vector and then cultured for an additional 2 or 4 days as indicated. Cells were collected and stained for CD34 and CD38 and analyzed by flow cytometry for the frequency of GFP+ cells in the CD34+ subset (solid columns), the CD34+CD38– subset (cross-hatched columns), or the CD34+CD38+ subset (open columns). The percentage of GFP+ cells in each subset was normalized to the percentage of GFP+CD34+ cells obtained with the amphotropic pseudotype vectors within each experiment. Averages ± SD of two independent experiments are presented; the CD34+ subset analysis is representative of four additional experiments.

In an additional study, we cultured transduced CD34+ cells in medium designed to support the growth of erythroid precursors (GPA+), granulocyte precursors (CD11b+CD14–), or monocyte precursors (CD14+) and evaluated the marking frequency after 7 days (Table 4). These studies reveal that CatPac pseudotype vectors transduce progenitors capable of differentiating into erythroblasts, granulocytes, or monocytes at similar frequencies as CD34+CD38– cells whereas GALV pseudotype vectors preferentially target precursors that differentiate into granulocytes or monocytes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Transduction of CD34+-Derived Progenitor Cells

| |

Percentage of GFP+cellsa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging cells | CD34+ | CD34+CD38− | Erythroid | Granulocytes | Monocytes |

| Mock | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.66 | 0.17 |

| CatPac6 | 27.4 | 18.2 | 19.9 | 24.3 | 24.4 |

| CatPac7 | 26.4 | 17.6 | 20.3 | 23.7 | 21.9 |

| GALV | 47.8 | 22.9 | 23.2 | 50.9 | 44.6 |

Percentage of CD34+-derived cells marked 2 days (CD34+, CD34+CD38–) or 9 days (erythroid, granulocytes, monocytes) after transduction with the MGIN vector.

Mature hematopoietic cells can be transduced with CatPac vectors

Besides transduction of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, transduction of mature T cells and macrophages is also of therapeutic interest because both of these cell types have a relatively long life span and this could be used to treat disease, deficiencies, or some cancers (Hege and Roberts, 1996; Burke et al., 2002). Macrophages recycle senescent red blood cells and thus are exposed to high levels of heme and concomitantly have high levels of FLVCR (Khan et al., 1993; Keel et al., 2008). Primary macrophages are recalcitrant to transduction with simple retroviral vectors because mature macrophages are a nondividing cell type, requiring MOIs greater than 10 to achieve 10% marking frequency (Jarrosson-Wuilleme et al., 2006). Some macrophages isolated from bone marrow do have a limited capacity for cell division (Kennedy and Abkowitz, 1998), suggesting bone marrow-derived macrophages may be more amenable to transduction. We compared CatPac and Phoenix GALV pseudotype vectors with various regimens and found comparable but low transduction frequencies. On the basis of three similar experiments, CatPac pseudotype vectors transduced a maximum of 2.1% of CD14+CD163+ bone marrow-derived macrophages whereas Phoenix-GALV pseudotype vectors transduced a maximum of 1.2% of these cells.

FeLV-C induces thymic atrophy in infected cats (Rojko et al., 1992) and human lymph nodes express high levels of FLVCR mRNA (Tailor et al., 1999b). Purified and activated T cells express a level of FLVCR more than 2-fold greater than control (data not shown), and thus they are a possible target for CatPac pseudotype vectors. We transduced activated T cells from three separate donors and found that CatPac-produced vectors are capable of transducing 15–19% of activated peripheral blood T cells whereas GALV pseudotype vectors transduced 30–36%.

Discussion

The CatPac packaging system targets a novel, widely expressed cell surface receptor and thus provides an alternative method for vector delivery to diverse cell types. The broad host range of FeLV-C (Jarrett et al., 1973; Riedel et al., 1988) indicates that CatPac-produced vectors are able to transduce cells from many species, including dog, primate, and human, but not mouse or rat. FLVCR is expressed on almost all hematopoietic cells (Abkowitz et al., 1987; Khan et al., 1993; Quigley et al., 2004) and CatPac can effectively target vector delivery to hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro. With CD34+ cells, we found that GALV pseudotype vectors had about 2-fold higher transduction frequencies than CatPac and Phoenix-Ampho pseudotype vectors (Table 4 and Fig. 2; and see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). However, there was no difference in marking frequency on day 4 between the CD34+ and CD34+CD38– subsets with vectors produced by CatPac whereas vectors produced by Phoenix-GALV and Phoenix-Ampho transduced the CD34+CD38– subset at 38 and 42% of the frequency of transduction of total CD34+ cells. This preferential targeting of the more primitive subset of CD34+ cells by CatPac pseudotype vectors compared with GALV pseudotype vectors can explain the discrepancy between lower marking of total CD34+ cells (this study) and the results of Lucas and colleagues (2005). CatPac pseudotype vectors may target HSCs, which are a small fraction of CD34+CD38– cells, at levels comparable to progenitor cells. This is consistent with FeLV-C receptor (FLVCR) mRNA levels being high in more primitive progenitor cells and decreased during later differentiation (Quigley et al., 2004) and the in utero sheep transplantation studies demonstrating that FeLV-C pseudotype vectors targeted human HSCs more effectively than GALV pseudotype vectors (Lucas et al., 2005).

Although CatPac-produced vectors are capable of transducing mature macrophages comparably to GALV, they did so at low frequencies, as expected because macrophages do not divide frequently. Optimization of the transduction protocol to induce proliferation is likely to increase the transduction frequency. Marrow-derived macrophages are capable of homing to peripheral tissues after ex vivo manipulation (Kennedy and Abkowitz, 1998), and thus macrophages transduced via CatPac pseudotype vectors could then be used to treat lysosomal storage disorders, which are largely mediated via tissue macrophages, and respond to macrophage-based therapy (Ohashi et al., 2000).

T cells are difficult to transduce with gammaretroviruses; however, improved methods have increased marking frequency from less than 5% to more than 50% (Bunnell et al., 1995; Abad et al., 2002) and even higher by selection posttransduction (Rettig et al., 2003). Using a straightforward transduction method, CatPac-produced vectors were able to transduce nearly 20% of activated T cells. Optimization of the transduction protocols is likely to increase the transduction frequency. Because FLVCR is directly involved in the regulation of iron/heme homeostasis (Keel et al., 2008), expression levels may be responsive to cellular heme or iron status, comparable to the manner in which Pit1 is responsive to phosphate levels (Kavanaugh et al., 1994; Bunnell et al., 1995). Thus it may be possible to significantly increase the transduction efficiency of T cells or macrophages by modulation of cellular heme/iron status, analogous to the increase in transduction via GALV pseudotype vectors after manipulation of cellular phosphate levels, which led to dramatic increases in transduction frequency (Bunnell et al., 1995).

In addition to hematopoietic cells and cell lines, FLVCR is highly expressed on duodenum, liver, and kidney (Keel et al., 2008), and cell lines representative of these sites (Caco2, HepG2, and 293, respectively) are efficiently transduced by CatPac-produced vectors (Table 1). Only Caco2 was transduced better by a non-CatPac-produced vector, and thus CatPac can effectively target a broad array of cell types beyond hematopoietic cells.

The commonly used retroviral pseudotypes have limitations that make them less than ideal for gene delivery. Amphotropic and GALV pseudotype vectors are not stable under the conditions necessary for concentration. We have demonstrated that CatPac pseudotype vectors are readily concentrated and withstand long-term storage at 4°C to facilitate batch processing and can be refrozen with little loss in titer. The VSV-G pseudotype commonly used for lentiviral vectors can be concentrated; however, during production and during transduction at high MOI it can be cytotoxic (Burns et al., 1993), thus requiring production in an all-transient system and the toxicity can limit its effectiveness. CatPac targets vectors to a broadly expressed receptor and has no identified toxic side effects, making it potentially useful. The drawback of CatPac is that being a gammaretroviral packaging system, it has the same limitation of requiring cell division for efficient gene integration as other, similar viral systems. However, the stability of the FeLV-C Env enabling concentration suggests it is worthwhile to investigate whether it could be engineered to pseudotype lentiviral vectors, circumventing the requirement for cell division, retaining the ability to use FLVCR for vector entry, and enabling the development of stable lentiviral packaging lines that could reduce or eliminate lot variation of vector preparations. This would be useful to target HSCs, macrophages, and other cell types that are mostly quiescent (Jetmore et al., 2002) but express high levels of FLVCR (Quigley et al., 2004; Lucas et al., 2005).

In addition to CatPac being a helper virus-free stable packaging line, the parental virus has never been identified as causing any human disease. FeLV virions appear to be readily inactivated in humans because there are no reported cases of FeLV-infected or seroconverted humans despite being exposed to FeLV, which is endemic in the domesticated cat population (Hardy et al., 1976). Although this is beneficial from the safety standpoint, it may preclude CatPac from being used for in vivo vector delivery. If this in vivo inactivation occurs with CatPac-produced vectors, it may be possible to modify the envelope to eliminate this property, and thus engineering an FeLV-C-based packaging system for safe in vivo vector delivery may be feasible.

There are several different cell lines commonly used to titer retroviral vectors, and the choice of cell line can have a large influence on the resulting titers. We use the feline embryonic fibroblast cell line FEA for titering FeLV pseudotype vectors. One of the commonly used human cell lines, HT-1080, has a relatively low level of FLVCR and frequently indicates CatPac pseudotype vector titers 5- to 10-fold lower than those obtained with FEA cells. Nonetheless, vector supernatants from either CatPac line consistently have higher titers than those of identically produced Phoenix-Ampho or Phoenix-GALV pseudotypes generated from the same transfection mix on all human cell lines we have tested except for the Caco2 cell line (see Table 1). One contributing factor for the substantially higher titers with CatPac vectors may be the relatively long half-life of these vectors at 37°C. CatPac-produced vectors have half-lives of up to 15 hr at 37°C whereas the half-lives of other pseudotypes are 4 to 9 hr (Kaptein et al., 1997; Higashikawa and Chang, 2001; Segura et al., 2005); thus, during the course of the viral incubation, CatPac-produced virions remain active much longer and are still able to transduce cells during the later times after vectors with other pseudotypes have lost most of their activity.

A single stock of CatPac-produced vectors resulted in titers that varied up to 5-fold among the three human cell lines routinely used for titering, whereas amphotropic and GALV pseudotype vectors varied only up to 2-fold among the human cell lines. This variation in CatPac pseudotype vector titers can be explained by the various amounts of FLVCR expressed by these cells. Interestingly, when we used the feline FEA cell line, all vector preparations, including amphotropic and GALV pseudotypes, resulted in 5- to 10-fold higher titers than when measured on human cell lines. This discrepancy was observed with both GFP and neo vectors, and thus it was not due to pseudo-transduction by GFP. It is either caused by differences in receptor levels or postfusion processing and clearly demonstrates that the choice of line used for titering viral supernatants has a direct impact on the resulting titer and thus the reported MOI. Furthermore, particles thought to be inactive on the basis of titering results from one cell line may be active on another cell line. In this case, using FEA cells reveals there are actually up to 10-fold more active virions in vector stocks than would be reported by titering on HT-1080 cells. Because we use FEA as our preferred titering line, our reported titers may be higher and our MOIs will actually be lower than in other reports that use these human cell lines to determine titer.

We developed CatPac to be a safe, helper-free, packaging system composed entirely of FeLV-C components. We separated gag-pol and env components to develop a stable packaging line with increased safety compared with the 61EC-based construct, which is an intact virus lacking the packaging signal (Quigley et al., 2000; Lucas et al., 2005). CatPac-produced vectors are stable at 4°C, can withstand the high-speed centrifugation required for concentration and medium exchange, and can be refrozen with little loss of titer. These features make CatPac a flexible packaging system that provides unique benefits for human gene therapy. Although the stability of the vectors is primarily a property of the FeLV-C Env, using the structural components from the same species may account for some of the additional stability and high titers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julie Overbaugh (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) and Derek Persons (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital) for providing retroviral vectors. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL31823 (J.L.A.), DK47754 (A.D.M.), and M01-RR-00037 (General Clinical Research Center, University of Washington).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

References

- Abad J.L. Serrano F. San Roman A.L. Delgado R. Bernad A. Gonzalez M.A. Single-step, multiple retroviral transduction of human T cells. J. Gene Med. 2002;4:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abkowitz J.L. Retrovirus-induced feline pure red cell aplasia: Pathogenesis and response to suramin. Blood. 1991;77:1442–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abkowitz J.L. Holly R.D. Grant C.K. Retrovirus-induced feline pure red cell aplasia: Hematopoietic progenitors infected with feline leukemia virus and erythroid burst-forming cells are uniquely sensitive to heterologous complement. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;80:1056–1063. doi: 10.1172/JCI113160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abkowitz J.L. Taboada M.R. Sabo K.M. Shelton G.H. The ex vivo expansion of feline marrow cells leads to increased numbers of BFU-E and CFU-GM but a loss of reconstituting ability. Stem Cells. 1998;16:288–293. doi: 10.1002/stem.160288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell B.A. Muul L.M. Donahue R.E. Blaese R.M. Morgan R.A. High-efficiency retroviral-mediated gene transfer into human and nonhuman primate peripheral blood lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:7739–7743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke B. Sumner S. Maitland N. Lewis C.E. Macrophages in gene therapy: Cellular delivery vehicles and in vivo targets. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;72:417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C.C. Moser M. Banks J. Alderete J.P. Overbaugh J. Identification and deletion of sequences required for feline leukemia virus RNA packaging and construction of a high-titer feline leukemia virus packaging cell line. Virology. 1996;222:14–20. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J.C. Friedmann T. Driever W. Burrascano M. Yee J.K. Vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein pseudotyped retroviral vectors: concentration to very high titer and efficient gene transfer into mammalian and nonmammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:8033–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L. Du C. Murray D. Tong X. Zhang Y.A. Chen B.P. Hawley R.G. A GFP reporter system to assess gene transfer and expression in human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Gene Ther. 1997;4:1013–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybing J. Lynch C.M. Hara P. Jurus L. Kiem H.P. Anklesaria P. GaLV pseudotyped vectors and cationic lipids transduce human CD34+ cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 1997;8:1685–1694. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.14-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham F.L. Smiley J. Russell W.C. Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy W.D., Jr. Hess P.W. MacEwen E.G. McClelland A.J. Zuckerman E.E. Essex M. Cotter S.M. Jarrett O. Biology of feline leukemia virus in the natural environment. Cancer Res. 1976;36:582–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hege K.M. Roberts M.R. T-cell gene therapy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1996;7:629–634. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashikawa F. Chang L. Kinetic analyses of stability of simple and complex retroviral vectors. Virology. 2001;280:124–131. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn P.A. Topp M.S. Morris J.C. Riddell S.R. Kiem H.P. Highly efficient gene transfer into baboon marrow repopulating cells using GALV-pseudotype oncoretroviral vectors produced by human packaging cells. Blood. 2002;100:3960–3967. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett O. Laird H.M. Hay D. Determinants of the host range of feline leukaemia viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1973;20:169–175. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-20-2-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrosson-Wuilleme L. Goujon C. Bernaud J. Rigal D. Darlix J.L. Cimarelli A. Transduction of nondividing human macrophages with gammaretrovirus-derived vectors. J. Virol. 2006;80:1152–1159. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1152-1159.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetmore A. Plett P.A. Tong X. Wolber F.M. Breese R. Abonour R. Orschell-Traycoff C.M. Srour E.F. Homing efficiency, cell cycle kinetics, and survival of quiescent and cycling human CD34+ cells transplanted into conditioned NOD/SCID recipients. Blood. 2002;99:1585–1593. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson N.C. Sabo K.M. Abkowitz J.L. Transduction of feline hematopoietic cells by oncoretroviral vectors pseudotyped with the subgroup A feline leukemia virus (FeLV-A) Mol. Ther. 2000;2:56–62. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein L.C. Greijer A.E. Valerio D. van Beusechem V.W. Optimized conditions for the production of recombinant amphotropic retroviral vector preparations. Gene Ther. 1997;4:172–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh M.P. Miller D.G. Zhang W. Law W. Kozak S.L. Kabat D. Miller A.D. Cell-surface receptors for gibbon ape leukemia virus and amphotropic murine retrovirus are inducible sodium-dependent phosphate symporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:7071–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel S.B. Doty R.T. Yang Z. Quigley J.G. Chen J. Knoblaugh S. Kingsley P.D. De Domenico I. Vaughn M.B. Kaplan J. Palis J. Abkowitz J.L. A heme export protein is required for red blood cell differentiation and iron homeostasis. Science. 2008;319:825–828. doi: 10.1126/science.1151133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy D.W. Abkowitz J.L. Mature monocytic cells enter tissues and engraft. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:14944–14949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan K.N. Kociba G.J. Wellman M.L. Macrophage tropism of feline leukemia virus (FeLV) of subgroup-C and increased production of tumor necrosis factor-α by FeLV-infected macrophages. Blood. 1993;81:2585–2590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas M.L. Seidel N.E. Porada C.D. Quigley J.G. Anderson S.M. Malech H.L. Abkowitz J.L. Zanjani E.D. Bodine D.M. Improved transduction of human sheep repopulating cells by retrovirus vectors pseudotyped with feline leukemia virus type C or RD114 envelopes. Blood. 2005;106:51–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.D. Buttimore C. Redesign of retrovirus packaging cell lines to avoid recombination leading to helper virus production. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1986;6:2895–2902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.8.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.D. Garcia J.V. von Suhr N. Lynch C.M. Wilson C. Eiden M.V. Construction and properties of retrovirus packaging cells based on gibbon ape leukemia virus. J. Virol. 1991;65:2220–2224. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2220-2224.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi T. Yokoo T. Iizuka S. Kobayashi H. Sly W.S. Eto Y. Reduction of lysosomal storage in murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII by transplantation of normal and genetically modified macrophages. Blood. 2000;95:3631–3633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlic D. Girard L.J. Jordan C.T. Anderson S.M. Cline A.P. Bodine D.M. The level of mRNA encoding the amphotropic retrovirus receptor in mouse and human hematopoietic stem cells is low and correlates with the efficiency of retrovirus transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:11097–11102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbaugh J. Donahue P.R. Quackenbush S.L. Hoover E.A. Mullins J.I. Molecular cloning of a feline leukemia virus that induces fatal immunodeficiency disease in cats. Science. 1988;239:906–910. doi: 10.1126/science.2893454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons D.A. Allay J.A. Allay E.R. Ashmun R.A. Orlic D. Jane S.M. Cunningham J.M. Nienhuis A.W. Enforced expression of the GATA-2 transcription factor blocks normal hematopoiesis. Blood. 1999;93:488–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley J.G. Burns C.C. Anderson M.M. Lynch E.D. Sabo K.M. Overbaugh J. Abkowitz J.L. Cloning of the cellular receptor for feline leukemia virus subgroup C (FeLV-C), a retrovirus that induces red cell aplasia. Blood. 2000;95:1093–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley J.G. Yang Z. Worthington M.T. Phillips J.D. Sabo K.M. Sabath D.E. Berg C.L. Sassa S. Wood B.L. Abkowitz J.L. Identification of a human heme exporter that is essential for erythropoiesis. Cell. 2004;118:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasko J.E. Battini J.L. Gottschalk R.J. Mazo I. Miller A.D. The RD114/simian type D retrovirus receptor is a neutral amino acid transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:2129–2134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig M.P. Ritchey J.K. Meyerrose T.E. Haug J.S. Dipersio J.F. Transduction and selection of human T cells with novel CD34/thymidine kinase chimeric suicide genes for the treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Mol. Ther. 2003;8:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel N. Hoover E.A. Gasper P.W. Nicolson M.O. Mullins J.I. Molecular analysis and pathogenesis of the feline aplastic anemia retrovirus, feline leukemia virus C-Sarma. J. Virol. 1986;60:242–250. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.242-250.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel N. Hoover E.A. Domsife R.E. Mullins J.I. Pathogenic and host range determinants of the feline aplastic anemia retrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:2758–2762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojko J.L. Fulton R.M. Rezanka L.J. Williams L.L. Copelan E. Cheney C.M. Reichel G.S. Neil J.C. Mathes L.E. Fisher T.G. Lymphocytotoxic strains of feline leukemia virus induce apoptosis in feline T4-thymic lymphoma cells. Lab. Invest. 1992;66:418–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino D.E. Do B.Q. Pyle L.C. Seidel N.E. Girard L.J. Spratt S.K. Orlic D. Bodine D.M. Amphotropic or gibbon ape leukemia virus retrovirus binding and transduction correlates with the level of receptor mRNA in human hematopoietic cell lines. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 1997;23:422–433. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1997.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura M.M. Kamen A. Trudel P. Garnier A. A novel purification strategy for retrovirus gene therapy vectors using heparin affinity chromatography. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005;90:391–404. doi: 10.1002/bit.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailor C.S. Nouri A. Zhao Y. Takeuchi Y. Kabat D. A sodium-dependent neutral-amino-acid transporter mediates infections of feline and baboon endogenous retroviruses and simian type D retroviruses. J. Virol. 1999a;73:4470–4474. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4470-4474.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailor C.S. Willett B.J. Kabat D. A putative cell surface receptor for anemia-inducing feline leukemia virus subgroup C is a member of a transporter superfamily. J. Virol. 1999b;73:6500–6505. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6500-6505.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.