Abstract

Context

Improving the quality of mental health care requires moving clinical interventions from controlled research settings into “real world” practice settings. While such advances have been made for depression, little work has been done for anxiety disorders.

Objective

To determine whether a flexible treatment-delivery model for multiple primary care anxiety disorders (panic, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and/or posttraumatic stress disorders) would be superior to usual care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized controlled effectiveness trial of CALM (“Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management”) compared to usual care (UC) in 17 primary care clinics in 4 US cities. Between June 2006 and April 2008, 1004 patients with anxiety disorders (with or without major depression), age 18–75, English- or Spanish-speaking, enrolled and subsequently received treatment for 3–12 months. Blinded follow-up assessments at 6, 12, and 18 months after baseline were completed in October 2009.

Intervention(s)

CALM allowed choice of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), medication, or both; included real-time web-based outcomes monitoring to optimize treatment decisions and a computer-assisted program to optimize delivery of CBT by non-expert care managers who also assisted primary care providers in promoting adherence and optimizing medications.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

12-item Brief Symptom Inventory (anxiety and somatic symptoms) score. Secondary outcomes: Proportion of responders (≥ 50% reduction from pre-treatment BSI-12 score) and remitters (total BSI-12 score < 6).

Results

Significantly greater improvement for CALM than UC in global anxiety symptoms: BSI-12 group differences of −2.49 (95% CI, −3.59 to −1.40), −2.63 (95% CI, −3.73 to −1.54), and −1.63 (95% CI, −2.73 to −0.53) at 6, 12, and 18 months, respectively. At 12 months, response and remission rates (CALM vs. UC) were 63.66% (58.95–68.37) vs. 44.68% (39.76–49.59), and 51.49% (46.60–56.38) vs. 33.28% (28.62–37.93), with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5.27 (4.18–7.13) for response and 5.5 (4.32–7.55) for remission.

Conclusions

For patients with anxiety disorders treated in primary care clinics, a collaborative care intervention, compared to usual care, resulted in greater improvement in anxiety symptoms, functional disability, and quality of care over 18 months.

Improving the quality of mental health care requires continued efforts to move evidence-based treatments of proven efficacy into “real world” practice settings with wide variability in patient characteristics and provider skill.1 The effectiveness of one approach, “collaborative care”, is well established for primary care depression2–5 but has been infrequently studied for anxiety disorders,6, 7 despite their common occurrence in primary care.8 The multiplicity of anxiety disorders, and the fact that anxious patients are less likely to seek9 and harder to engage10 in treatment, likely are contributing factors. Furthermore, whereas effective treatment for both anxiety and depressive disorders relies in part on pharmacotherapy, psychosocial treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are important for anxious patients. Not only do they strongly prefer psychological treatment over medications,10, 11 but CBT may have advantages over pharmacotherapy in terms of maintaining clinical improvements over time.12, 13

In response to primary care provider preferences for interventions that have the capacity to address a range of common mental disorders rather than just one, we designed a flexible treatment delivery model, CALM (“Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management”),14 and compared its effectiveness to care as usual. CALM addresses the four most common anxiety disorders–panic disorder (PD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)–even when they co-occur with depression. CALM optimizes treatment engagement by allowing choice of treatment modality15 (pharmacotherapy and/or CBT) and provision of additional treatment when needed.2 A web-based outcomes system is used to facilitate measurement-based care16 and a computer-assisted program helps guide non-expert care managers in delivering evidence-based CBT.17 In this way, CALM seeks to accommodate the complexity of real-world clinical settings, while maximizing fidelity to the evidence-base in the context of a broad range of patients, providers, practice settings, and payers.

We hypothesized that CALM would be superior to usual care (UC) in reducing psychic and somatic symptoms of anxiety and in improving global measures of functioning, health-related quality of life, and quality of care delivered. We expected small to moderate effect sizes similar to those found in previous collaborative care studies for depression.

METHODS

Setting, Subjects, and Design

Between June 2006 and April 2008, 1004 primary care patients with PD, GAD, SAD, and/or PTSD were enrolled in the CALM study. A total of 17 clinics in Little Rock, LA County, San Diego and Seattle, serving > 35,000 patients with > 780,000 annual visits, were purposively selected based on a number of considerations, including provider interest, space availability, size and diversity of the patient population, and insurance mix. Primary care providers (120 internists and 28 family physicians) referred all potential subjects, facilitated by an optional five question anxiety screener.18 To determine eligibility, referred subjects met with a specially trained clinician, the Anxiety Clinical Specialist (ACS). The 14 ACS (11 female, 3 male) included 6 social workers, 5 RNs, 2 master’s level psychologists and 1 PHD psychologist. Eight had some mental health experience, 4 were familiar with but had no formal training with CBT, and 7 had some psychopharmacology experience.

Eligible subjects were patients at participating clinics, 18–75 years old, who met DSM-IV criteria for one or more of PD, GAD, SAD, or PTSD (based on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview19 administered by the ACSs after formal training and diagnostic reliability testing), and scored at least 8 (moderate anxiety symptoms on a scale ranging from 0–20) on the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS), validated as clinically significant in a separate analysis.20 Co-occurring major depression was permitted. Persons unlikely to benefit from CALM (ie, unstable medical conditions, marked cognitive impairment, active suicidal intent or plan, psychosis, bipolar I disorder, substance abuse of dependence except for alcohol and marijuana abuse) were excluded. Subjects already receiving ongoing CBT or medication from a psychiatrist (N = 7) were excluded, as were persons who could not speak English or Spanish (N = 2). All subjects gave informed, written consent for the study, which was approved by each institution’s Institutional Review Board.

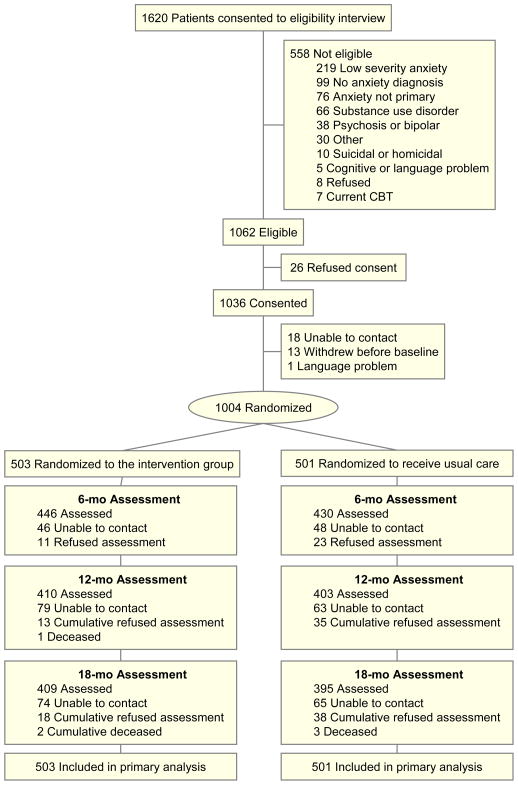

After a baseline interview (see below) subjects were randomized to CALM or UC, using an automated computer program at RAND, where all post-eligibility assessments were conducted by phone. Randomization was stratified by clinic and presence of co-morbid major depression, using a permuted block design. Block size was masked to all clinical site study members. The CONSORT diagram describes patient flow from eligibility screening through consent and randomization (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of Participants.

Non-response was related to younger age, less education, higher BSI-12 and OASIS scores at 6 months; younger age, higher BSI-12, Sheehan Disability and OASIS scores, higher rate of panic, and higher rate among Hispanics at 12 months; and younger age, higher BSI-12 and OASIS scores, lower preference for current health state, higher rate of panic, and higher rate among Hispanics at 18 months.

Intervention (CALM)/Usual Care (UC)

CALM used a web-based monitoring system,16 modeled on the IMPACT intervention,2 with newly developed anxiety content, and a computer-assisted CBT program.17 ACSs received six half days of didactics, which focused on mastering the CBT program, plus motivational interviewing (modified for anxiety concerns) to enhance engagement, outreach strategies for ethno-racial and impoverished minorities, and a medication algorithm for anxiety.21 CBT training also included role-playing, and required successful completion of two training patients over several months.

CALM patients initially received their preferred treatment, either medication, CBT, or both, over 10 to 12 weeks. Since the effects of CBT delivered for one disorder are known to generalize to co-morbid disorders,22 patients with multiple anxiety disorders were asked to choose the most disabling or distressing disorder to focus on with the expectation that their co-morbid disorders would also improve. The CBT program, a “repackaging” based on already validated CBT treatments,23 included 5 generic modules (education, self-monitoring, hierarchy development, breathing training, relapse prevention) and 3 modules (cognitive restructuring, exposure to internal and external stimuli) tailored to the four specific anxiety disorders. CBT was administered by the ACS (typically in 6 to 8 weekly sessions), while medication was prescribed. A local study psychiatrist provided single session medication management training to providers using a simple algorithm, as needed consultation by phone or e-mail, and very rarely, a face to face assessment for complex or treatment refractory patients. The algorithm emphasized first line use of SSRI or SNRI antidepressants, dose optimization, side effect monitoring, followed by second and third step combinations of two antidepressants or an antidepressant and benzodiazepine for refractory patients.21 For medication management, the ACS provided adherence monitoring, counseling to avoid alcohol and optimize sleep hygiene and behavioral activity, and relayed medication suggestions from the supervising psychiatrist to the PCP.

The ACS tracked patient outcomes on a web-based system by entering scores for the OASIS and a 3-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and examining graphical progress over time. The goal was either clinical remission, defined as an OASIS < 5 = “mild”, sufficient improvement such that the patient did not want further treatment, or improvement with residual symptoms or other emergent problems requiring a non-protocol psychotherapy (ie, DBT, family or dynamic psychotherapy). Symptomatic patients thought to benefit from additional treatment with CBT or medication could receive more of the same modality (“stepping up”) or the alternative modality (“stepping over”), for up to three more steps of treatment. After treatment completion, patients were entered into “continued care” and received monthly follow-up phone calls to reinforce CBT skills and/or medication adherence. ACSs interacted regularly with PCPs in person and over the phone. PCPs remained the clinician of record and prescribed all medications. All ACSs received weekly supervision from a psychiatrist and psychologist.

UC patients continued to be treated by their physician in the usual manner with no intervention, ie, with medication, counseling (7 of 17 clinics had limited in-clinic mental health resources, usually a single provider with limited familiarity with evidence based psychotherapy24) or referral to a mental health specialist. After the eligibility diagnostic interview, the only contact UC patients had with study personnel was for assessment by phone.

Assessments

The assessment battery was administered at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months via centralized phone survey by the RAND Survey Research Group who were blinded to treatment assignment. The last subject was assessed in October 2009. Because prior studies indicated outcome differences by ethno-racial groupings,3 race-ethnicity data was obtained by subject self-report using standard classification. The primary outcome was a generic measure of two key components of all anxiety disorders, psychic and somatic anxiety: the Brief Symptom Inventory subscales for anxiety and somatization (total 12 items, BSI-1225). Response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction on the BSI-12, or meeting the definition of remission, and remission was defined as a face-valid per item score of < 0.5 (between “none” and “mild”, total BSI-12 score < 6) consistent with previous analyses using the BSI for depression outcomes.26 Secondary measures included PHQ-8 depression,27 anxiety sensitivity (ASI),28 and functional status (Sheehan Disability29, the CDC Healthy Days Measure of restricted activity days,30 and SF-12v231). Quality of care was measured by patient self-report of psychotropic medication type, dose, and adherence, and number and consistency of CBT elements occurring in reported psychotherapy sessions.32 More detailed information on CALM patients’ number and type (CBT vs. medication/care management) of sessions was extracted from the web-based management system.

Analysis

During the proposal phase, we had assumed an attrition rate of 28% at month 18. Therefore, we had anticipated needing a sample size of 1040 to detect effect sizes of 0.3 standard deviations with at least 80% power. Although the enrolled sample size (N = 1004) was marginally smaller than projected, subject attrition was lower (20% at month 18), yielding a larger than anticipated sample size at the follow-up time points.

We compared demographics and baseline anxiety and depression disorders rates by intervention group using t-tests and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables respectively. To estimate the intervention effect over time we jointly modeled the outcomes at the four assessment times (baseline and 3 follow-ups at 6, 12 and 18 months) by time, intervention, the interaction of time and intervention, and site. Time was treated as a categorical variable. To avoid restrictive assumptions, the covariance of the outcomes at the four assessment times was left unstructured. We fitted the proposed model using a restricted maximum likelihood approach, which produces valid estimates under the missing-at-random assumption.33 This approach correctly handles the additional uncertainty arising from missing data and uses all available data to obtain unbiased estimates for model parameters.34 This is an efficient way for conducting an intent-to-treat analysis since it includes all the subjects with a baseline assessment. For cross-sectional analyses (such as those assessing the percentage of responders at the 3 follow-up times), we used attrition weights to correctly account for those subjects that missed one or more follow-up assessments35 The statistical software used was SAS version 9. All P values were 2-tailed and are adjusted using Hochberg’s36 correction method to account for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Sample Selection, Attrition, and Description

Figure 1 depicts study subject flow and reasons for non-eligibility. Two-thirds of referred patients (1062/1620 [66%]) were eligible for the study, a majority of these (1036/1062 [98%]) consented to participate, and a majority (1004/1036 [97%]) were randomized. Over 80% of subjects were assessed at each evaluation window and study retention was high and similar in both study arms. Table 1 shows that the sample was 70% female, ethnically diverse (44% non-white), and broad in age range. It was a fairly ill group with over half having at least two chronic medical conditions and at least two anxiety disorders, and two-thirds with co-morbid major depression. CALM and UC were comparable on all these dimensions.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristicsa

| All (n = 1004) | Interventionb (n = 503) | Usual Careb (n = 501) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43.47 (13.44) | 43.3 (13.2) | 43.7 (13.7) |

| Women | 714 (71.12) | 359 (71.4) | 355 (70.9) |

| Education < High school |

55 (5.49) |

29 (5.77) |

26 (5.21) |

| 12 y | 165 (16.47) | 78 (15.5) | 87 (17.4) |

| > 12 y | 782 (78.04) | 396 (78.7) | 386 (77.4) |

| Ethnicity Hispanic |

196 (19.52) |

104 (20.7) |

92 (18.4) |

| African American | 116 (11.55) | 51 (10.1) | 65 (13.0) |

| White | 568 (56.57) | 279 (55.5) | 289 (57.7) |

| Other | 124 (12.35) | 69 (13.7) | 55 (11.0) |

| No. of chronic medical conditions 0 |

202 (20.14) |

109 (21.7) |

93 (18.6) |

| 1 | 219 (21.83) | 108 (21.5) | 111 (22.2) |

| ≥ 2 | 582 (58.03) | 285 (56.8) | 297 (59.3) |

| Anxiety disorderc Panic |

475 (47.31) |

235 (46.7) |

240 (47.9) |

| Generalized anxiety | 756 (75.30) | 390 (77.5) | 366 (73.1) |

| Social phobia | 405 (40.34) | 210 (41.8) | 195 (38.9) |

| Posttraumatic stress | 181 (18.03) | 92 (18.3) | 89 (17.8) |

| Major depressive disorder | 648 (64.54) | 330 (65.6) | 318 (63.5) |

| Type of health insurancec Medicaid |

101 (10.08) |

47 (9.4) |

54 (10.8) |

| Medicare | 124 (12.38) | 60 (12.0) | 64 (12.8) |

| Other government insuranced | 35 (3.49) | 16 (3.2) | 19 (3.79) |

| Private insurance | 749 (74.75) | 372 (74.3) | 377 (75.3) |

| No insurance | 141 (14.07) | 77 (15.4) | 64 (12.8) |

Data are reported as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

There are no significant differences in any of the baseline characteristics between intervention and usual care patients.

Because patients could have more than one, Ns may total more than 1004.

Includes Veterans’ Administration benefits, TRICARE, county programs, or other government insurance not otherwise specified.

Intervention (CALM) Participation

After the baseline assessment, 482 of 503 (95%) subjects randomized to CALM had at least one intervention contact. Over the course of the year, subjects had 7.0 +/− 4.1 (Median = 8) CBT visits (1% [35/3,386] by phone, < 1% [11/3,386] focused on depression) and 2.24 +/− 3.57 (Median = 1) medication/care management visits (43% [462/1,078] by phone). Of the 482 subjects, 166 (34%) had only CBT visits, 43 (9%) had only medication/care management visits, and 273 (57%) had some of both. Visits for 218 (45%) subjects were confined to the first three months and 424 (88%) subjects had all visits by 6 months. A small proportion of subjects (69/482 [14%]) also had an in-person visit with the study psychiatrist.

Quality of Care

Table 2 depicts self-reported Quality of Care received at baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months for the two groups, using progressively more stringent definitions of care quality. At both 6 (54.83 % [95% CI, 51.00–58.66] vs 9.98 % [95% CI, 6.08–13.88]) and 12 (21.64 % [95% CI, 18.19–25.09] vs 9.31 % [95% CI, 5.83–12.79]) month assessments, significantly more CALM subjects received psychotherapy with at least 3 of 6 CBT elements (eg, exposure, relaxation, cognitive restructuring, homework) usually or always delivered. At 6 months only, significantly more CALM subjects either took medication of appropriate21 type, dose and duration (≥ 2 months) or had an appropriate change in medication (dose increase or medication switch/addition) if they were already on medication: 25.35% (95% CI, 21.28–29.43%) vs. 17.11% (95% CI, 13.51–20.70). Rates of overall psychotropic use did not differ between CALM and UC over time.

Table 2.

Anxiety Carea

| Intervention | Usual Care | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Psychotropic Medication | |||

| Baseline | 64.4 (60.2–68.6) | 62.1 (57.9–66.3) | 0.94 |

| 6 months | 69.9 (65.7–74.1) | 68.3 (64.1–72.5) | 0.94 |

| 12 months | 66.3 (61.9–70.8) | 64.0 (59.5–68.4) | 0.94 |

| 18 months | 61.4 (56.9–66.0) | 61.2 (56.5–65.8) | 0.94 |

| Any Appropriateb Anti-Anxiety Medication at Appropriate Dose for ≥ 2 Months | |||

| Baseline | 29.0 (25.0–33.0) | 30.6 (26.6–34.7) | 0.94 |

| 6 months | 46.4 (41.9–51.0) | 41.5 (36.9–46.1) | 0.94 |

| 12 months | 42.1 (37.5–46.7) | 36.0 (31.4–40.6) | 0.94 |

| 18 months | 40.8 (36.3–45.4) | 37.5 (32.8–42.1) | 0.94 |

| Medication Change During First 6 Monthsc,e | |||

| 6 months | 25.4 (21.3–29.4) | 17.1 (13.5–20.7) | 0.05 |

| Medication Change During Second 6 Monthsd,e | |||

| 12 months | 13.1 (9.73–16.5) | 12.1 (8.80–15.3) | 0.94 |

| Any Counseling | |||

| Baseline | 45.9 (41.6–50.3) | 46.7 (42.3–51.1) | 0.94 |

| 6 months | 88.1 (84.2–92.0) | 51.0 (47.1–55.0) | <.001 |

| 12 months | 58.4 (53.7–63.2) | 46.3 (41.5–51.1) | 0.01 |

| 18 months | 39.1 (34.4–43.8) | 42.6 (37.8–47.4) | 0.94 |

| Counseling with ≥ 3 CBT Elementsf | |||

| Baseline | 20.5 (16.9–24.1) | 22.0 (18.4–25.5) | 0.94 |

| 6 months | 82.1 (78.2–86.1) | 33.6 (29.6–37.7) | <.001 |

| 12 months | 49.1 (44.5–53.6) | 26.6 (22.1–31.2) | <.001 |

| 18 months | 26.2 (22.0–30.5) | 27.7 (23.4–32.1) | 0.94 |

| Counseling with ≥ 3 CBT Elementsf Delivered Consistentlyg | |||

| Baseline | 4.37 (2.56–6.19) | 4.59 (2.78–6.41) | 0.94 |

| 6 months | 54.8 (51.0–58.7) | 9.98 (6.08–13.9) | <.001 |

| 12 months | 21.6 (18.2–25.1) | 9.31 (5.83–12.8) | <.001 |

| 18 months | 9.91 (7.07–12.8) | 8.91 (6.02–11.8) | 0.94 |

Abbreviation: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

Data are presented as percentage (95% confidence interval). All time effects were significant at P <.001 in all models including four time points. Intervention × time effects based on the WALD test were significant at P <.001 for all three counseling models.

Defined as medication of appropriate type, dose and duration (≥2 months) or had an appropriate change (dose increase or medication switch/addition) if they were already on medication.

Medication change calculated based on 430 control and 446 intervention patients who responded at 6 months, weighted for non-response.

Medication change calculated based on 391 control and 397 intervention patients who responded at 6 and 12 months, weighted for non-response.

The P values for medication change come from a χ2 test on data weighted for attrition. All other P values come from the longitudinal models (eg, given the estimates of the longitudinal model we obtained the predicted means at the four time points by intervention group and tested their difference at every time point using the correct t-test).

Defined as receiving psychotherapy with at least 3 of 6 CBT elements (eg, exposure, relaxation, cognitive restructuring, homework).

Defined as receiving psychotherapy with at least 3 of 6 CBT elements usually or always delivered.

Outcomes

Table 3 examines trajectories of adjusted means over time for the primary BSI-12 outcome, and for all secondary outcomes. BSI-12 scores were significantly lower for CALM subjects at 6 (Δ 2.49 points [95% CI, −3.59 to −1.40], P <.001), 12 (Δ 2.63 points [95% CI, −3.73 to −1.54], P <.001) and 18 months (Δ 1.63 points [95% CI, −2.73 to −0.53], P =.05), with effects sizes of 0.30 (0.43–0.17), 0.31 (0.44–0.18), and 0.18 (−.30–0.06). Outcomes for intervention patients were significantly better for all other measures except physical health and satisfaction with medical care. Effect sizes were small to medium depending on the measure, and were greatest at 12 months. There were no significant differences in intervention effect over time by site, and all four disorders showed significant effects on the main BSI-12 outcome (eTable 1 [http://www.jama.com]).

Table 3.

Adjusted Means for Anxiety Outcomesa

| Interventionb | Usual Careb | Difference (95% CI) | P Value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-12) Score | |||||

| Baseline | 16.38 (15.60 to 17.17) | 16.24 (15.46 to 17.03) | 0.14 (−0.97 to 1.25) | 0.90 | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.18) |

| 6 months | 9.19 (8.42 to 9.95) | 11.68 (10.90 to 12.46) | −2.49 (−3.59 to −1.40) | <0.001 | −0.30 (−0.43 to −0.17) |

| 12 months | 8.22 (7.45 to 8.99) | 10.85 (10.07 to 11.63) | −2.63 (−3.73 to −1.54) | <0.001 | −0.31 (−0.44 to −0.18) |

| 18 months | 8.21 (7.43 to 8.98) | 9.84 (9.05 to 10.62) | −1.63 (−2.73 to −0.53) | 0.05 | −0.18 (−0.30 to −0.06) |

| Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI) Score | |||||

| Baseline | 29.57 (28.37 to 30.78) | 29.89 (28.68 to 31.10) | −0.32 (−2.03 to 1.39) | 0.90 | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.08) |

| 6 months | 19.69 (18.41 to 20.96) | 24.00 (22.71 to 25.29) | −4.31 (−6.13 to −2.50) | <0.001 | −0.31 (−0.44 to −0.18) |

| 12 months | 17.37 (16.10 to 18.64) | 22.11 (20.83 to 23.40) | −4.74 (−6.55 to −2.93) | <0.001 | −0.34 (−0.47 to −0.21) |

| 18 months | 16.80 (15.52 to 18.08) | 20.37 (19.08 to 21.67) | −3.57 (−5.39 to −1.76) | 0.002 | −0.26 (−0.39 to −0.13) |

| Depression (PHQ-8) Score | |||||

| Baseline | 12.60 (12.07 to 13.12) | 12.47 (11.94 to 12.99) | 0.13 (−0.61 to 0.87) | 0.90 | 0.02 (−0.09 to 0.13) |

| 6 months | 7.48 (6.93 to 8.02) | 9.05 (8.49 to 9.60) | −1.57 (−2.35 to −0.79) | 0.002 | −0.25 (−0.37 to −0.12) |

| 12 months | 6.64 (6.07 to 7.22) | 8.87 (8.28 to 9.45) | −2.22 (−3.05 to −1.40) | <0.001 | −0.37 (−0.51 to −0.23) |

| 18 months | 6.47 (5.92 to 7.03) | 7.92 (7.36 to 8.49) | −1.45 (−2.24 to −0.66) | 0.006 | −0.24 (−0.37 to −0.11) |

| Sheehan Disability Score | |||||

| Baseline | 16.77 (16.14 to 17.40) | 17.15 (16.51 to 17.78) | −0.38 (−1.27 to 0.52) | 0.90 | −0.05 (−0.17 to 0.07) |

| 6 months | 9.14 (8.42 to 9.86) | 11.63 (10.89 to 12.36) | −2.49 (−3.52 to −1.46) | <0.001 | −0.32 (−0.46 to −0.19) |

| 12 months | 8.24 (7.50 to 8.97) | 11.69 (10.94 to 12.43) | −3.45 (−4.49 to −2.40) | <0.001 | −0.44 (−0.59 to −0.32) |

| 18 months | 8.37 (7.62 to 9.12) | 10.89 (10.13 to 11.65) | −2.52 (−3.59 to −1.45) | <0.001 | −0.35 (−0.47 to −0.19) |

| Physical Health Composite Score (SF-12v2) | |||||

| Baseline | 49.02 (48.02 to 50.02) | 49.32 (48.32 to 50.32) | −0.30 (−1.71 to 1.11) | 0.90 | −0.03 (−0.17 to 0.11) |

| 6 months | 47.81 (46.79 to 48.83) | 47.23 (46.20 to 48.25) | 0.59 (−0.86 to 2.03) | 0.90 | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.17) |

| 12 months | 47.72 (46.68 to 48.77) | 47.82 (46.77 to 48.87) | −0.10 (−1.58 to 1.38) | 0.90 | −0.01 (−0.16 to 0.14) |

| 18 months | 48.22 (47.18 to 49.26) | 47.35 (46.30 to 48.40) | 0.87 (−0.61 to 2.35) | 0.90 | 0.08 (−0.05 to 0.22) |

| Mental Health Composite Score (SF-12v2) | |||||

| Baseline | 31.64 (30.76 to 32.51) | 32.06 (31.19 to 32.94) | −0.43 (−1.66 to 0.81) | 0.90 | −0.04 (−0.15 to 0.07) |

| 6 months | 43.98 (42.94 to 45.01) | 39.99 (38.93 to 41.04) | 3.99 (2.52 to 5.47) | <0.001 | 0.34 (0.21 to 0.47) |

| 12 months | 45.65 (44.54 to 46.76) | 40.29 (39.17 to 41.41) | 5.36 (3.78 to 6.93) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.33 to 0.61) |

| 18 months | 45.64 (44.57 to 46.71) | 41.75 (40.67 to 42.84) | 3.89 (2.37 to 5.42) | <0.001 | 0.39 (0.24 to 0.54) |

| Healthy Days Score | |||||

| Baseline | 11.46 (10.60 to 12.32) | 11.16 (10.30 to 12.03) | 0.30 (−0.92 to 1.52) | 0.90 | 0.04 (−0.12 to 0.20) |

| 6 months | 5.74 (4.96 to 6.51) | 7.81 (7.02 to 8.60) | −2.07 (−3.18 to −0.97) | 0.005 | −0.24 (−0.37 to −0.11) |

| 12 months | 5.77 (4.95 to 6.58) | 7.51 (6.68 to 8.33) | −1.74 (−2.90 to −0.58) | 0.05 | −0.21 (−0.35 to −0.07) |

| 18 months | 5.06 (4.28 to 5.84) | 6.94 (6.15 to 7.73) | −1.88 (−3.00 to −0.77) | 0.02 | −0.19 (−0.30 to −0.08) |

| Satisfaction with Overall Health Care Score | |||||

| Baseline | 3.68 (3.59 to 3.77) | 3.75 (3.66 to 3.84) | −0.07 (−0.20 to 0.06) | 0.90 | −0.06 (−0.17 to 0.05) |

| 6 months | 4.17 (4.07 to 4.26) | 3.75 (3.66 to 3.85) | 0.41 (0.28 to 0.55) | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.27 to 0.54) |

| 12 months | 4.03 (3.93 to 4.13) | 3.80 (3.70 to 3.90) | 0.22 (0.08 to 0.37) | 0.03 | 0.22 (0.08 to 0.37) |

| 18 months | 3.88 (3.77 to 3.98) | 3.79 (3.68 to 3.89) | 0.09 (−0.06 to 0.24) | 0.90 | 0.09 (−0.06 to 0.24) |

| Satisfaction with Mental Health Care Score | |||||

| Baseline | 3.23 (3.14 to 3.33) | 3.27 (3.17 to 3.36) | −0.03 (−0.17 to 0.10) | 0.90 | −0.03 (−0.17 to 0.10) |

| 6 months | 4.16 (4.06 to 4.26) | 3.38 (3.28 to 3.49) | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.72 (0.59 to 0.86) |

| 12 months | 3.88 (3.78 to 3.99) | 3.36 (3.26 to 3.47) | 0.52 (0.37 to 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.34 to 0.62) |

| 18 months | 3.66 (3.55 to 3.77) | 3.40 (3.29 to 3.51) | 0.26 (0.10 to 0.41) | 0.02 | 0.24 (0.09 to 0.38) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PHQ-8, Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-12v2, SF-12v2 Health Survey.

All time effects were significant at P <.001 in all models. Intervention × time effects based on the WALD test were significant at P <.001 in all models for all outcomes except for the Physical Health Composite Score. All P values come from the longitudinal models (eg, given the estimates of the longitudinal model we obtained the predicted means at the four time points by intervention group and tested their difference at every time point using the correct t-test).

Data are presented as adjusted mean (95% confidence interval).

Table 4 shows that a significantly (P < .001) higher proportion of CALM subjects responded and remitted, respectively. Response (including remission) rates at 6, 12, and 18 months were 57.46% (52.84–62.08), 63.66% (58.95–68.37), 64.64% (59.95–69.32) vs. 36.80% (32.21–41.39), 44.68% (39.76–49.59), 51.47% (46.49–56.45) (CALM vs. UC); remission rates 45.40% (38.78–48.03), 51.49% (46.60–56.38), 51.06% (46.16–55.96) vs. 27.49% (23.25–31.72), 33.28% (28.62–37.93), 36.77% (31.99–41.55). The number needed to treat (defined as 1/difference between intervention and control response or remission) at 12 months was 5.27 (4.18–7.13) for response and 5.5 (4.32–7.55) for remission.

Table 4.

Proportion Achieving Response and Remission From Baseline BSI-12 Scorea

| Intervention | Usual Care | NNT (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responseb | ||||

| 6 months | 289/503 (57.46) | 185/501 (36.80) | 4.84 (3.93–6.29) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 320/503 (63.66) | 224/501 (44.68) | 5.27 (4.18–5.27) | <0.001 |

| 18 months | 325/503 (64.64) | 258/501 (51.47) | 7.59 (5.51–12.22) | <0.001 |

| Remissionc | ||||

| 6 months | 218/503 (43.40) | 138/501 (27.49) | 6.28 (4.83–9.98) | <0.001 |

| 12 months | 259/503 (51.49) | 167/501 (33.28) | 5.5 (4.32–7.55) | <0.001 |

| 18 months | 257/503 (51.06) | 184/501 (36.77) | 7.0 (5.19–10.75) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BSI-12, Brief Symptom Inventory; CI, confidence interval; NNT, number needed to treat.

Data presented as proportion (percentage) weighted for non-response at each follow-up.

Response defined as ≥ 50% reduction on the BSI-12, with all those in remission considered to have responded.

Remission defined as a per item BSI-12 score of <0.5 (total score <6).

COMMENT

These findings document the feasibility, acceptability (or satisfaction), and clinical effectiveness of a care delivery model designed to treat persons with any of four common anxiety disorders across 17 primary care clinics varying in patient characteristics, payer types, and organization. The model utilized both real time outcomes monitoring and a computer-guided, modular CBT program which assured a high degree of fidelity in CBT application. Even though different anxiety disorders (with or without depression) were targeted with this single intervention, effect sizes were similar to those obtained in previous anxiety effectiveness studies that had focused solely on panic disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder.6, 7 Importantly, the number needed to treat (NNT) was well within the range for treatments in medicine that are generally considered to be efficacious,37, 38 and beneficial effects of the intervention persisted for at least one year after clinical visits had ceased, suggesting a longer term effect.

This study has a number of limitations. It was designed to test delivery of a blended package of treatments known to be evidence-based and we cannot determine which components of the blended intervention (eg, preference, CBT, medication, web-outcomes monitoring) accounted for the results. Subjects, a third of whom had failed at least one course of pharmacotherapy, were relatively well-educated and were referred to the study, all of which may have enhanced CBT engagement and response. We relied on self-report, rather than review of medical records, to assess amount and quality of treatment and used a relatively lean assessment battery intended to cover more domains while minimizing subject burden. The participating clinics had a higher than usual amount of in-house mental health resources in usual care, though this may have led to an underestimate of the benefit of CALM vs UC.

The positive outcomes as a whole may have been mediated by higher rates of quality CBT at 6 and 12 months and higher quality medication treatment at 6 months. This improved quality of care was facilitated by real-time outcomes monitoring, which allowed for adjustment of type and amount of delivered treatment, and a computer-guided modular CBT program, which assured high fidelity when delivered by non-experts, though the relative contribution of each to improved outcomes cannot be determined. The high rate of selection of CBT treatment by patients confirms previous findings11, 39 that anxious patients prefer psychosocial treatment approaches. Also the persistence of anxiety despite pharmacologic treatment in over half the sample at baseline may have further reinforced this preference. Because the intervention devoted most of its training resources to the CBT program, it is possible that the medication management component could be further improved with more focus on this modality.

The flexibility of treatment (eg, variation in number and type of sessions, and in criteria for continuing further treatment, use of both phone and in person contact), the targeting of multiple disorders, and the clinical effectiveness across a range of patients and clinics, suggest that the CALM treatment delivery model should be broadly applicable in primary care. However, implementation of this model will require reimbursement mechanisms for care management that are not currently available. In this vein, forthcoming analyses about the cost of CALM will be needed to help payers decide whether to support its uptake in clinical settings. Furthermore, the in-house model used by CALM would be less feasible for small or rurally-located practices, which might require a more centrally located care manager and perhaps internet or telephone delivery in order to serve multiple small and/or remote practices. Nonetheless, the success of the model tested here demonstrates that addressing multiple common mental disorders in the context of one delivery model is feasible and effective and could serve as a template for the development of unified approaches to management of the multiple psychiatric co-morbidities that are the rule, rather than the exception, in both the general population40 and in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the following grants from the National Institute of Mental Health: U01 MH057858 and K24 MH065324 (Dr Roy-Byrne), U01 MH058915 (Dr Craske), U01 MH070022 (Dr Sullivan), U01 MH070018 (Dr Sherbourne), U01MH057835 and K24 MH64122 (Dr Stein).

Role of the Sponsor: The CALM study’s oversight was managed by the National Institute of Mental Health DSMB which has a rotating panel of members. The National Institute of Mental Health had no other involvement with the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Scientific Advisory Board: Frank Verlain deGruy, III, MD, MSFM (Department of Family Medicine, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine, Aurora); Wayne Katon, MD, and Jürgen Unützer, MD, MPH, MA (Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle); Lisa V. Rubenstein, MD, MSPH, FACP (Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine and VA Greater Los Angeles Center of Excellence for the Study of Healthcare Provider Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles; and RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California); Kenneth Wells, MD, MPH (Jane and Terry Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior and Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles; Department of Health Services, UCLA School of Public Health; and RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California). These board members received compensation for their consultation.

Ethnic Advisory Board: Peter J. Guarnaccia, PhD (Department of Human Ecology and the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey); Maga Jackson-Triche, MD, MSHS (VA Northern California Health Care System and University of California Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento); Jeanne Miranda, PhD (Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles); David T. Takeuchi, PhD (School of Social Work and Department of Sociology, University of Washington, Seattle). These board members received compensation for their consultation.

Additional Contributions:

Anxiety Clinical Specialists: Skye M. Adams, LMSW, and Sandy Sanders, MSW, LCSW (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock); Michelle Behrooznia, MA, Shadha Hami Cissell, MSW, and Michele S. Smith, PhD (University of California, San Diego); Cindy Chumley (High Desert Medical Group, Lancaster, California); Laura Constantinides, RN (Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego County) Margie Fort, MSW, LICSW, Alice S. Friedman, MSN, ARNP, Kelly H. Koo, MS, Molly Roston, MSW, and Jodi Rubinstein, LICSW (University of Washington, Seattle); James W. Miller, MA, CRC (Desert Medical Group, Palm Springs, California); Angelica Ruiz, CCRC (Desert Oasis Healthcare, Palm Desert, California). These individuals were compensated for their work on the project.

Supervising Psychiatrists: C. Winston Brown, MD, Mohit Chopra, MD, and Dan-Vy Mui, MD (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock); James W. Gaudet, MD (Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego County); Stuart Levine, MD, MHA (University of California, Los Angeles, and HealthCare Partners, Torrance, California); R. Christopher Searles, MD, FAAFP (University of California, San Diego); Jason P. Veitengruber, MD (University of Washington at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle). These individuals were compensated for their work on the project.

Primary Care Clinic Champions: Lee C. Abel, MD (Little Rock Diagnostic Clinic, Little Rock, Arkansas); Basil Abramowitz, MD, and Stacey Coleman, DO (Sharp Rees Stealy, San Diego County, California); Lisa D. Chew, MD, MPH, and Robert Crittendon, MD (Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Washington); Matthew G. Deneke, MD (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock); Anne M. Eacker, MD (University of Washington Medical Center Roosevelt, Seattle); Erwin Guzman, MD (Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego County); Ralph Joseph, MD (St. Vincent’s Family Clinic, Little Rock, Arkansas); Gene A. Kallenberg, MD (University of California, San Diego); Richard Kovar, MD, FAAFP, and Carrie Rubenstein, MD (Country Doctor Community Health Centers, Seattle, Washington); T. Putnam “Putter” Scott, MD (Neighborcare Health, Seattle, Washington); Ivan Womboldt, CRCC (Desert Medical Group, Palm Springs, California). These individuals were compensated for work on this project either directly or via administrative fee payments to their clinics.

RAND Survey Research Group: Barbara Levitan, BA (RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California. Ms. Levitan was compensated for work on this project.

Translators: Velma Barrios, MA (University of California, Los Angeles); Avelina Martinez, MAT, ATA-Certified Translator from English into Spanish (Austin, TX). These individuals were compensated for their work on this project.

Proficiency Raters: Laura B. Allen, PhD, and Ancy E. Cherian, PhD (University of California, Los Angeles). These individuals were compensated for their work on this project.

Analysis: Bernadette Benjamin, MS (RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California); Jutta M. Joesch, PhD, and Imara I. West, MPH (University of Washington, Seattle). These individuals were compensated for their work on the project.

Programming of web-based outcomes system: Youlim Choi, MS (University of Washington, Seattle). Mr. Choi was compensated for his work on this project.

Programming of computer CBT program: Vivid Concept LLC (www.vividconcept.com).

Study Coordinators: Kristin Bumgardner, BS (University of Washington, Seattle and central coordination of overall study); Daniel Dickson, BA, Daniel Glenn, BA, and Michael E.J. Reding, MA (University of California, Los Angeles); Christina Reaves, MPH (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock). These individuals were compensated for their work on the project.

National Institute of Mental Health: Matthew V. Rudorfer, MD (Adult Treatment and Preventive Interventions Research Branch, Division of Services and Intervention Research (DSIR), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and Elizabeth Zachariah, MS (Clinical Trials Operations and Biostatistics Unit (CTOB), Division of Services and Intervention Research (DSIR), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Previous Presentations: Parts of this article were presented at the annual meeting of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America, Baltimore, Maryland, March 5, 2010.

Additional Information: eTable 1 is available at http://www.jama.com.

Author Contributions: Dr Sherbourne had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund, Lang, Bystritsky, Welch, Chavira, Golinelli, Campbell-Sills, Sherbourne, Stein.

Acquisition of data: Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund, Lang, Bystritsky, Welch, Chavira, Golinelli, Campbell-Sills, Sherbourne, Stein.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Golinelli, Sherbourne, Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Stein.

Drafting of the manuscript: Roy-Byrne.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund, Lang, Bystritsky, Welch, Chavira, Golinelli, Campbell-Sills, Sherbourne, Stein.

Statistical analysis: Golinelli, Sherbourne.

Obtaining funding: Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Sherbourne, Stein.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund, Lang, Bystritsky, Welch, Chavira, Golinelli, Campbell-Sills, Sherbourne, Stein.

Supervision: Roy-Byrne, Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund, Lang, Bystritsky, Welch, Chavira, Campbell-Sills, Sherbourne, Stein.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00347269

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Financial Disclosures: Dr Roy-Byrne reported receiving research grant support from the National Institutes of Health; having served as a paid member of advisory boards for Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Solvay Pharmaceuticals (one meeting for each); having received honoraria for CME-sponsored speaking from the American Psychiatric Association, Anxiety Disorders Association of America, CME LLC, CMP Media, Current Medical Directions, Imedex, Massachusetts General Hospital Academy, and PRIMEDIA Healthcare; and serving as Editor-in-Chief for Journal Watch Psychiatry (Massachusetts Medical Society) and Depression and Anxiety (Wiley-Liss Inc). Dr Roy-Byrne has also served as an expert witness on multiple legal cases related to anxiety; none involving pharmaceutical companies or specific psychopharmacology issues. Dr Bystritsky reported having served as a paid consultant for Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr Stein reported receiving or having received research support from the US Department of Defense, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, National Institutes of Health, and the US Veterans Affairs Research Program. Dr Stein is currently or has been a paid consultant for AstraZeneca, Avera Pharmaceuticals, BrainCells Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Comprehensive NeuroScience; Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche Pharmaceuticals, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, Mindsite, Pfizer, Sepracor, and Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc. Drs. Craske, Sullivan, Rose, Edlund, Lang, Welch, Chavira, Golinelli, Campbell-sills and Sherbourne all report no financial interests or relationships.

References

- 1.Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research--“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. Randomized trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):550–554. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(10):924–932. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication for primary care panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):290–298. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, Mazumdar S, et al. A randomized trial to improve the quality of treatment for panic and generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(12):1332–1341. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein MB, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, et al. Quality of care for primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2230–2237. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(1):77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grilo CM, Money R, Barlow DH, et al. Pretreatment patient factors predicting attrition from a multicenter randomized controlled treatment study for panic disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(6):323–332. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazlett-Stevens H, Craske MG, Roy-Byrne PP, Sherbourne CD, Stein MB, Bystritsky A. Predictors of willingness to consider medication and psychosocial treatment of panic disorder in a primary care sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(5):316–321. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadiga DN, Hensley PL, Uhlenhuth EH. Review of the long-term effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy compared to medications in panic disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17(2):58–64. doi: 10.1002/da.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuzenroeder L, Donnelly M, Haby MM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological interventions for generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(8):602–612. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan G, Craske MG, Sherbourne C, et al. Design of the Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM) study: innovations in collaborative care for anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ. 2001;322(7289):772–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unutzer J, Choi Y, Cook IA, Oishi S. A web-based data management system to improve care for depression in a multicenter clinical trial. Psyc Services. 2002;53(6):671–673. 678. doi: 10.1176/ps.53.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craske MG, Rose RD, Lang A, et al. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in primary-care settings. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(3):235–242. doi: 10.1002/da.20542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Means-Christensen A, CDS, Roy-Byrne P, MGC, MBS Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: the anxiety and depression detector (ADD) Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-IV adn ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(supp 20):22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell-Sills L, Norman SB, Craske MG, et al. Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1–3):92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy-Byrne P, Veitengruber JP, Bystritsky A, et al. Brief intervention for anxiety in primary care patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(2):175–186. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.02.080078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsao JCI, Mystkowski J, Zucker B, Craske MG. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder on comorbid conditions: Replication and extension. Behav Ther. 2002;33:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev Jan. 2006;26(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, et al. National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):925–934. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derogatis L. BSI-18: Brief Symptom Inventory 18 administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry Oct. 2001;158(10):1638–1644. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the predictions of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11 (Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CDC. Measuring Healthy Days. Atlanta, Georgia: CDC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bowker D, Gandek B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 health survey (with a Supplement Documenting Version 1) Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steketee G, Perry JC, Goisman RM, et al. The psychosocial treatments interview for anxiety disorders. A method for assessing psychotherapeutic procedures in anxiety disorders. J Psychother Pract Res. 1997;6(3):194–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Joh Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brick JM, Kalton G. Handling missing data in survey research. Stat Methods Med Res Sep. 1996;5(3):215–238. doi: 10.1177/096228029600500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochberg Y. A sharper bonferroni procedure for multiple significance testing. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–803. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Chang D. Reporting number needed to treat and absolute risk reduction in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2002;287(21):2813–2814. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.21.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore A. What is Number Needed to Treat. Evidence-Based Thinking about Health Care. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feeny NC, Zoellner LA, Mavissakalian MR, Roy-Byrne PP. What would you choose? Sertraline or prolonged exposure in community and PTSD treatment seeking women. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(8):724–731. doi: 10.1002/da.20588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.