Abstract

Current bone tissue engineering strategies aim to grow a tissue similar to native bone by combining cells and biologically active molecules with a scaffold material. In this study, a macroporous scaffold made from the seaweed-derived polymer alginate was synthesized and mineralized for cell-based bone tissue engineering applications. Nucleation of a bone-like hydroxyapatite mineral was achieved by incubating the scaffold in modified simulated body fluids (mSBF) for four weeks. Analysis using scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive x-ray analysis indicated growth of a continuous layer of mineral primarily composed of calcium and phosphorous. X-ray diffraction analysis showed peaks associated with hydroxyapatite, the major inorganic constituent of human bone tissue. In addition to the mineral characterization, the ability to control nucleation on the surface, into the bulk of the material, or on the inner pore surfaces of scaffolds was demonstrated. Finally, human MSCs attached and proliferated on the mineralized scaffolds and cell attachment improved when seeding cells on mineral coated alginate scaffolds. This novel alginate- HAP composite material could be used in bone tissue engineering as a scaffold material to deliver cells, and perhaps also biologically active molecules.

Keywords: Tissue engineering, scaffold, biomineralization

Introduction

A scaffold material is used in many bone tissue engineering applications as a vehicle to deliver cells and biologically active molecules, with the aim to grow a tissue similar to native bone. General properties that are desirable for the design of tissue engineering scaffolds include biocompatibility with the site of implantation, degradability into non toxic byproducts, adequate porosity to allow for cell infiltration and diffusion of nutrients and wastes, and vascularization. Other properties that are more specific for the design of bone tissue engineering scaffolds include integration with the developing tissue at the site of implantation, enhanced “osteoconductivity” and “osteoinductivity”, and mechanical support 1–5. Osteoconductivity refers to the ability of a material to serve as a template for bone-forming cells to attach, migrate, grow and form new tissue. Osteoinductivity typically requires the presence of bioactive molecules and/or cells that actively induce bone regeneration.

Natural bone is a composite material containing primarily type I collagen and carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite (HAP). Due to its osteoconductivity, and similar composition to natural bone, HAP has been used as a coating on metal implants to improve bone bonding 6 and in the fabrication of bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Results of pioneering studies by Kokubo and coworkers indicated that it is possible to grow nanocrystalline, carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite minerals similar to bone mineral on a variety of materials using a process that mimics natural biological mineralization 7. This process involves the use of a solution that approximates the ionic constituents, pH, and temperature of blood plasma - often termed simulated body fluids (SBF) – to nucleate and grow mineral on a template material with negatively charged or polar oxygen functional groups. This biomimetic approach has been successfully used by others to nucleate hydroxyapatite minerals on a variety of template materials, including glasses 8, metals 6, and polymers 9–11. Because the mineral is nucleated from an aqueous solution, this technique can be applied to scaffolds with complex porous geometry, unlike other surface modification methods that are limited to flat surfaces or very thin porous layers, such as plasma spraying 12, pulsed laser deposition 13, and electrophoretic deposition 14. Therefore, this biomimetic process may be particularly advantageous for coating of porous scaffold materials for tissue engineering applications, as demonstrated in recent studies 15,16.

In the current study, a macroporous scaffold made from the seaweed-derived polymer alginate was fabricated and mineral-coated using a biomimetic approach. Alginate was chosen as the base material since it presents a large number of pendant carboxylic acid groups, which provide sites for heterogeneous mineral nucleation, as demonstrated in previous studies with other carboxylic acid-containing materials 9,17,18. In addition, alginate has become an attractive material for tissue engineering due to its degradability under normal physiological conditions, mild processing, and low toxicity when purified. Specifically, in vitro studies have shown that cell types such as adipose tissue stromal cells, and osteoblasts can attach, proliferate and show osteogenic activity19–22. It has also been used as a scaffold material in vivo and has shown the ability to support deposition of a calcified matrix 22.

The morphology and composition of the mineral layer on the surface of alginate scaffolds in this study were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray diffraction. The ability of the mineral to support attachment and proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) was characterized, as hMSCs are capable of differentiating into cells of a diverse range of tissues, including bone, cartilage, and tendon 23, and they therefore represent an attractive cell type for orthopedic tissue engineering applications. Finally, the mineralization process was varied to achieve mineral nucleation on the surface or interior of macroporous scaffolds and in samples containing millimeter-scale channels. Results indicate that mineral-coated alginate scaffolds could be an appropriate carrier material for cell-based bone tissue engineering applications.

Materials and Methods

Alginate scaffold fabrication and incubation in mSBF

Alginic acid sodium salt from brown algae was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Macroporous alginate scaffolds were synthesized as previously reported by Shapiro et al 24. The three step process consisted of gelation of the alginate solution to form a hydrogel, then freezing, and finally drying by lyophilization. The alginate powder was first mixed with double distilled water to achieve a concentration of 3% (w/v) in a homogenizer at 50,000 rpm for 5 minutes. A 30mM CaCl2 solution was added to crosslink the alginate chains. Following the addition of the crosslinker, the alginate solution was mixed again at 50,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The solution was transferred either into a 24 well plate (well dimensions: 16 mm diameter, 20 mm height) or to a 48 well plate (well dimensions: 11.3 mm diameter, 20mm height) and frozen at -20°C. The solution was freeze dried overnight at low temperature (−60 °C) under vacuum (10μm Hg) to sublimate the ice crystals and develop the pore structure. Resulting scaffolds were cut prior to mineralization into disks that were between 3mm-7mm in thickness. To fabricate scaffolds with millimeter-scale channels for some experiments, the alginate solution (3% alginate in double distilled H2O crosslinked with CaCl2) was prepared in the same way described above and transferred to a 48 well plate, which was then covered with a custom made lid containing 19 stainless steel rods (1mm in diameter, 15 mm depth) in each well (Fig. 7A). The plate containing the alginate solution was then frozen at −20 °C and freeze dried overnight.

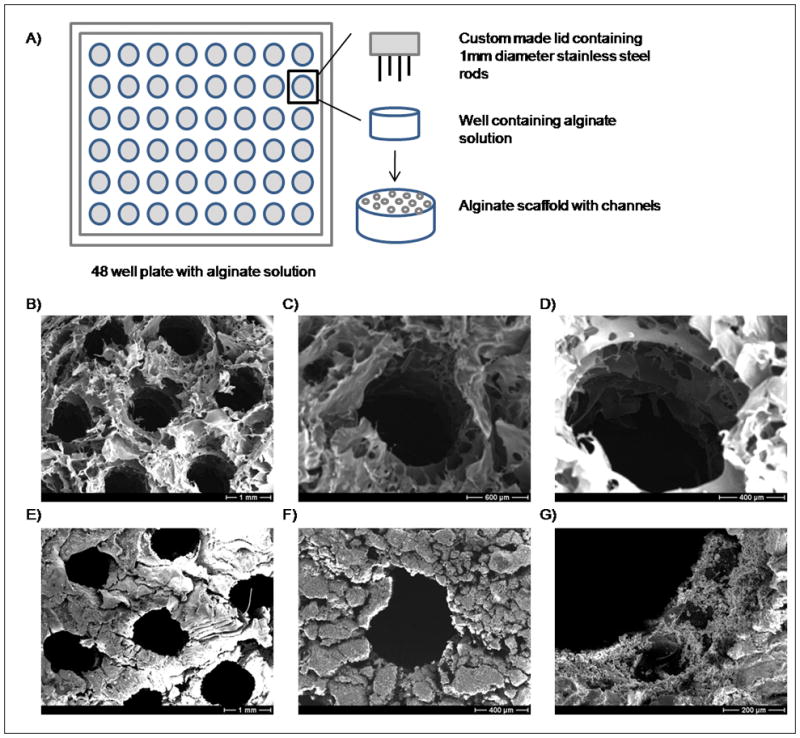

Figure 7.

A) Schematic representation of fabrication of scaffolds with cylindrical channels. B–G) SEM micrographs of the samples containing millimeter scaled channels (B–D) before and (E–G) after incubation in mSBF for 4 weeks.

Following fabrication, the outer surfaces of alginate scaffolds were cut and the resulting samples incubated at 37 °C in modified simulated body fluids (mSBF) for periods of 1, 2, 3, or 4 weeks under continuous rotation. A group of samples that did not have the outer surfaces removed was also incubated in mSBF. The volume of mSBF per outer surface area of the alginate scaffold used was approximately 10 ml/cm2. The mSBF solution had a similar composition to that of human plasma but with double the concentration of calcium and phosphate to enhance mineral growth, and was prepared as previously reported9. Specifically, the following reagents were added to ddH2O heated to 37 °C in the order shown; 141mM NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 20.0 mM Tris, 5.0 mM CaCl2, and 2.0 mM KH2PO4. The solution was then adjusted to a final pH of 6.8. The mSBF solution was renewed daily in order to maintain a consistent ionic strength throughout the experiment. For control experiments, the mSBF solution was prepared in a similar way the only difference being that it did not contain KH2PO4.

Material characterization

In order to assess mineral formation on the material, alginate scaffolds were collected at each time point; day 7, 14, 21, and 28 to determine the change in mass during the course of the experiment. Samples were rinsed at least twice in ddH2O to remove residual salts and then were freeze dried overnight in a lyophilizer at low temperature (−60 °C) under vacuum (10μm Hg). The mass was recorded and compared with the initial mass.

Analysis of mineral growth

The morphology and composition of the biomineral grown on the scaffolds was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Alginate samples mineralized for 4 weeks were mounted on aluminum stubs and sputter coated with a thin layer (600 Å) of carbon. Samples were imaged under high vacuum using a JEOL JSM-6100 scanning electron microscope operating at 15kV. An EDS detector was used together with the SEM for elemental analysis of the mineral. XRD patterns of the alginate surface of samples incubated in mSBF for 4 weeks were recorded using a General Area Detector Diffraction System (GADDS), with a Hi-star 2-D area detector (20° < 2θ < 40°) using Cu Kα radiation. The resulting patterns of the samples were identified by computer matching with an International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) powder diffraction database (ICDD card number for hydroxyapatite: 00-001-1008). Mineral composition was assessed with alginate samples incubated for 4 weeks since the coating appeared to be more continuous and dense at that time point.

Biological characterization

hMSCs culture on mineralized scaffolds

Alginate scaffolds (diameter=10.19 ±0.13 mm, thickness= 3.0 ±0.5 mm) were mineralized for 3 weeks, rinsed to eliminate residual salts, dried and sterilized using ethylene oxide gas which has been shown to have a less significant effect on the chemical composition and strength of other calcium- and phosphorous-based minerals than dry heat and autoclaving 25. Before cell seeding, the scaffolds were soaked in DMEM supplemented with 0.3g/l CaCO3 overnight. Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) purchased from Cambrex (Baltimore, MD) were expanded on tissue culture polystyrene plates according to the protocol provided by the supplier. Before evaluating proliferation of hMSCs on the alginate scaffolds, hMSCs seeded in tissue culture-treated polystyrene were cultured in medium containing 5mM CaCO3 or no CaCO3 supplement for 10 days to evaluate the effect of the calcium supplementation on hMSCs proliferation.

Cells at passage 6 were seeded at a density of 4 × 104 cells/cm2 on alginate scaffolds with or without the mineral coating and cultured using DMEM containing 15% FBS, and 0.3g/l CaCO3. On day one, the scaffolds were transferred into new 48 well plates and incubated for 21 days. The medium was supplemented with CaCO3 to maintain dimensional stability of the ionically crosslinked alginate scaffolds, which are compromised in the presence of calcium chelators (e.g. phosphates) and monovalent ions (e.g. Na, K) present in culture. The resulting concentration of calcium ion in the medium was approximately 5mM, which has been reported to be non-cytotoxic to osteoblasts. The medium was renewed daily to maintain a consistent calcium concentration.

Cell proliferation, viability and morphology

Cell viability was analyzed at various time points by staining cells with Calcein AM, which stains green for esterase activity in live cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and imaged on an Olympus IX51 inverted microscope. Metabolic activity of cells on the mineralized alginate scaffolds was assessed using the Cell Titer Blue (CTB) assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI), which measures cellular metabolic activity by measuring the ability of viable cells to reduce a resazurin dye to fluorescent resorufin. Resazurin was added to the samples and incubated for 4 hours as suggested by the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting solution was analyzed for fluorescence with a 560/20 excitation filter and a 590/35nm emission filter using a BioTek Synergy plate reader. The analytical assays were performed in each of the time points (1, 7, 14, and 21) with a sample number of n=6 and in replicates of 6 wells per sample.

Regulation of mineral nucleation site

Surface mineralization

Alginate scaffolds, fabricated with or without 1mm channels, with and without removing the outer surfaces were incubated at 37 °C in modified simulated body fluids (mSBF) for periods of 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks in continuous rotation using a Thermo Scientific Lab Quake rotator that operates at a speed of 8 rpm.

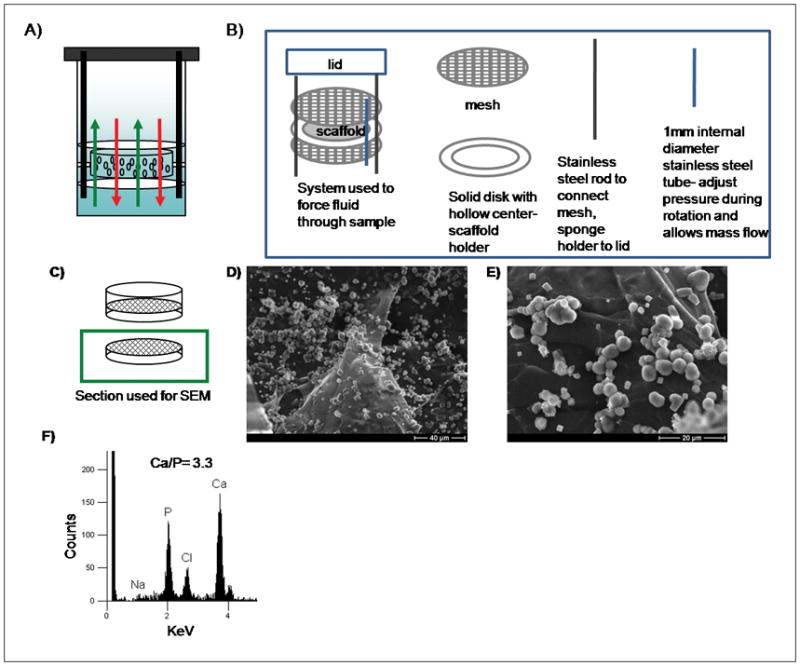

Interior mineralization

A custom made sample holder was prepared to force the mSBF solution through the pores of the scaffolds to promote mineral nucleation and growth on inner pore surfaces of the alginate scaffolds (Fig. 8A–B). The system consisted of two polymer meshes (20mm outer diameter, 1mm × 1mm mesh), a solid disk with a hollow center (20mm outside diameter, 8mm inside diameter), two stainless steel rods (2mm outside diameter) to connect the mesh-disk-mesh system to the lid of the vial, and a stainless steel tube open on both ends (1.75mm inside diameter, 2mm outside diameter) (Fig. 8B). The alginate scaffold was held by the solid disk and secured with the polymer meshes to prevent it from slipping out of the solid disk when wet. The stainless steel tube was used for the adjustment of the pressure in the system during rotation to ensure fluid flow. The samples were incubated in 20ml mSBF for 4 weeks, mSBF solution was renewed daily, and were rotated manually twice a day in order to allow the movement of the fluid through the sample.

Figure 8.

A) Schematic representation of system used to induce mineral formation in the interior of the porous scaffolds. B) Components of the system C–E) Schematic representation and SEM micrographs of mineral nucleated in the interior of the alginate scaffolds, resulting from forcing the mSBF solution to go through the pores of the material. F) Elemental analysis of an inner pore surface, demonstrating growth of a calcium phosphate mineral.

Micro CT Image Acquisition and Analysis

Alginate scaffolds incubated using regular rotation and forced systems were imaged in air using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT; GE Healthcare Explore MS-130 scanner: London, ON, Canada; www.gehealthcare.com). The system settings were 75 kVp and 75 mA with an aluminum filter, and data were acquired with an isotropic voxel size of 16 μm. The scanned images were reconstructed using Houndsfield unit calibration values which were performed with a phantom containing water, air and cortical bone mimic. The reconstructed images were analyzed using Microview 2.1.2 software (www.microview.sourceforge.net).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Differences between data sets were assessed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Mineral growth on alginate scaffolds

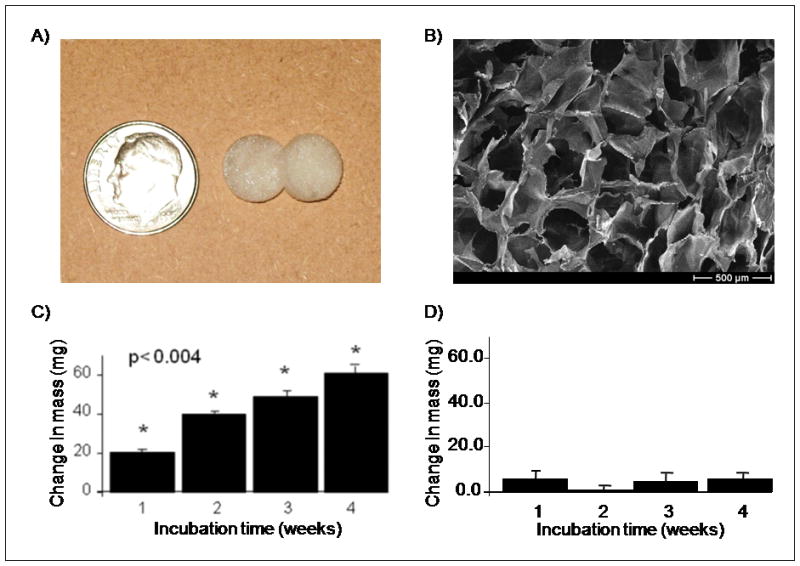

Incubation of alginate scaffolds in mSBF resulted in significant increases in the scaffold mass suggesting the growth of a mineral layer on the material over time (Fig. 1C). The increase in mass was significant among all the time points that were evaluated (p<0.05 for each group). Between the first and fourth week of incubation there is a 3-fold mass increase. In the control group the change in mass was small and remained relatively constant for the 4 week incubation period (Fig. 1D). A qualitative analysis based on SEM micrographs confirmed the continual growth of a mineral layer on the surface of the samples over time (Fig. 2A–D). Additionally, μCT data confirmed the formation of a coating in the outer surface of the scaffold (Fig. 9A).

Figure 1.

A) Macroscopic view of alginate scaffolds. B) SEM micrograph demonstrates that alginate scaffolds had open macropores. C–D) Change in mass of alginate scaffolds after 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks of incubation in C) mSBF and D) mSBF that did not contain KH2PO4 (control group). Increase in mass observed in the group of scaffolds incubated in mSBF showed significant differences in mass (p<0.05 in all groups).

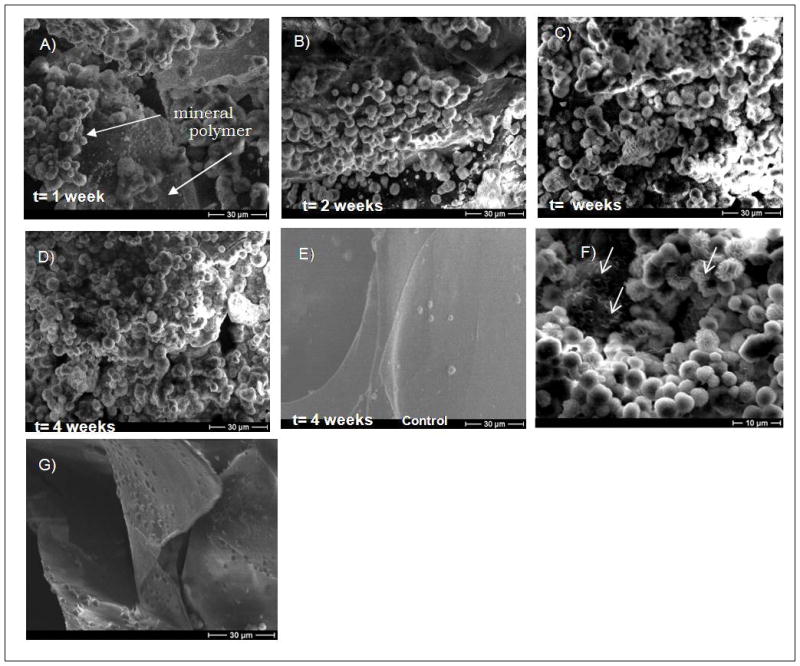

Figure 2.

Qualitative analysis of mineral growth after A) 1 week, B) 2 weeks, C) 3 weeks, D) 4 weeks, and E) 4 weeks, control group (mSBF without KH2PO4). SEM micrographs show that after 3 weeks a continuous mineral layer is formed. In the control group there is no evidence of mineral formation. F) Higher magnification of SEM micrograph of mineral nucleated on alginate scaffolds showed primarily a spherulitic morphology but a plate like morphology can be seen as well in the regions pointed by the arrows. G) SEM micrograph of the interior of a sample that was incubated in mSBF for 4 weeks showed no evidence of mineral nucleation.

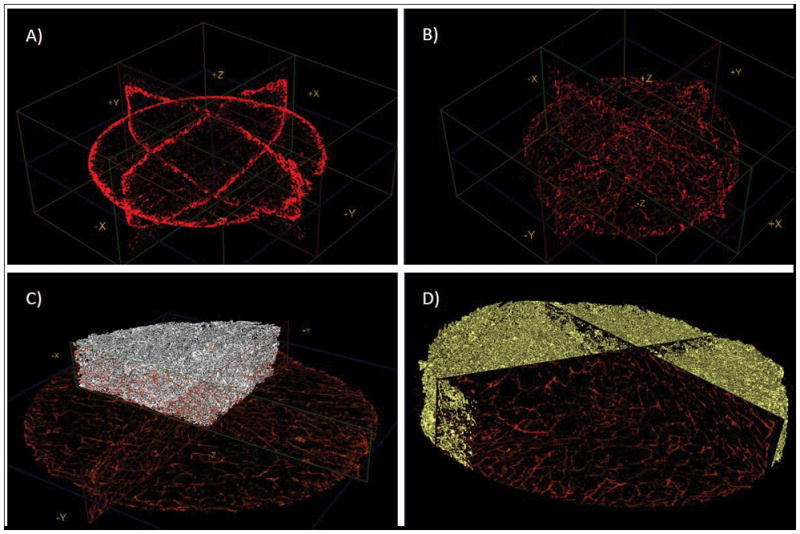

Figure 9.

μ-CT images of samples incubated using A) Regular rotation or B) Forced system. The red shade represents the mineral coating. It can be noted that in (A) only the surface of the scaffold contains a coating, whereas in (B) there is a three-dimensional distribution of the coating. Figures C) and D) show the coating in the forced system but the scan was done after scaffold embedding in PDMS to better demonstrate the distribution of the mineral coating.

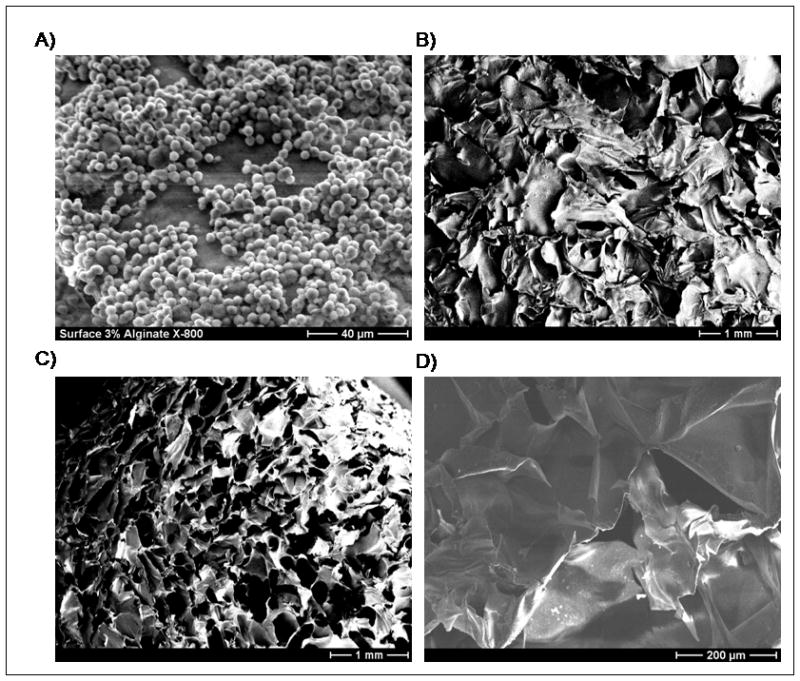

SEM images showed spherical particles on the surface of the scaffolds after 1 week of incubation (Fig. 2A). As the time of incubation increased (t= 2, 3, and 4 weeks) a more continuous layer was formed (Fig. 2B–D), and a fully continuous layer of mineral was observed on the surface of the scaffolds by 3 weeks. The control group showed no evidence of mineral formation (Fig. 2E). The small crystals observed in the control samples correspond to sodium chloride (NaCl), as confirmed by energy dispersive x-ray analysis (data not shown). The mineral nucleated on the alginate scaffolds displayed primarily a spherulitic morphology at the micrometer-scale (Fig. 2A–D), and a plate-like morphology at the nanometer-scale (Fig. 2F). Interestingly, mineral nucleation was observed on the surface of the scaffolds but not in the interior of the macropores (Fig. 2G, Fig. 3A). SEM micrographs of alginate scaffolds after fabrication exhibit lack of surface pores, but when the outer surfaces were removed an open pore structure was observed (Fig. 3B–C). Incubation of alginate scaffolds that did not have the outer surfaces removed showed no evidence of mineral formation on the inner pore walls.

Figure 3.

A) SEM micrograph of a mineral-coated alginate scaffold, suggesting “skin effects” from scaffold fabrication, since open pores are not observed on the mineral-coated surface. B) SEM micrograph of alginate scaffold after fabrication, exhibiting lack of surface pores, consistent with a “skin effect” during scaffold fabrication. C) SEM micrograph of alginate scaffold in which the outer surfaces were removed, showing an open pore structure. D) SEM micrograph of an alginate scaffold that had the outer surfaces cut off and was incubated in mSBF for 4 weeks, showing no evidence of mineral formation on the inner pore walls.

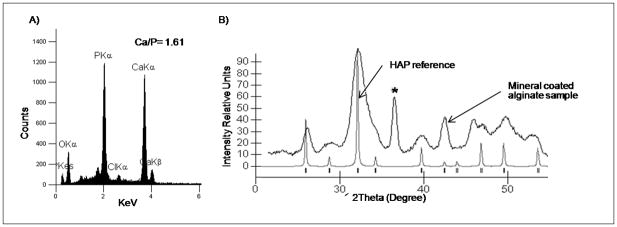

Biomineral composition and phase

The mineral nucleated on the scaffolds had an elemental composition and diffraction pattern consistent with HAP, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, the main inorganic component of natural bone tissue. The EDS profile of the alginate surface after incubation in mSBF for 4 weeks showed Ca and P peaks and a Ca/P ratio of 1.61 (Fig. 4A). The stoichiometric value of the Ca to P ratio associated with pure HAP is 1.67. X-ray diffraction analysis of the 4 week mineral coating on alginate samples revealed characteristic peaks of HAP (Fig. 4B). The XRD patterns of the grown layer exhibit broad peaks, which could indicate a smaller crystal size, a more amorphous mineral and the formation of carbonated HAP, which correlates better to bone apatite which is calcium deficient, poorly crystalline, and not a pure form of HAP.

Figure 4.

Characterization of biomineral grown on the outer surface of alginate scaffolds. A) EDS analysis demonstrates that the mineral nucleated is primarily composed of calcium and phosphorous with a Ca/P ratio of 1.6. B) XRD data confirms the nucleation of hydroxyapatite. * The peak at 35° <2θ< 40° was similar to the peak observed for aluminum which is the material that comprises the sample holder used for SEM analysis.

Biological characterization

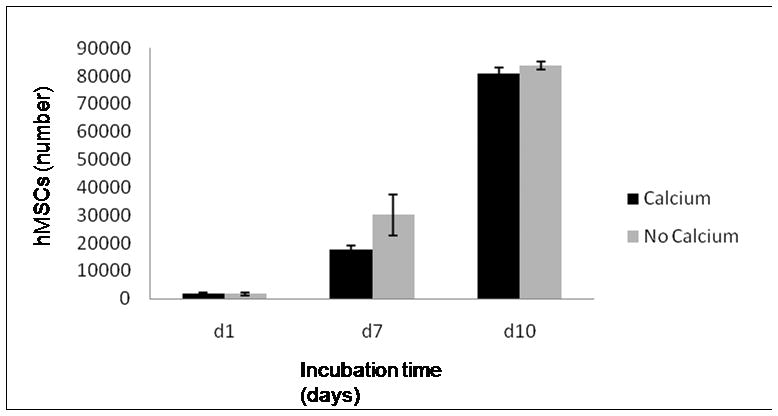

Human MSCs seeded on tissue culture-treated polystyrene in medium containing either 5mM CaCO3 or no CaCO3 supplement exhibited no significant differences in cell number during a 10 day incubation period (Fig. 5). The number of cells at day one was 1.8 × 103 ± 4.4 × 102 cells for the calcium supplemented group and 1.6 × 103 ± 5.4 × 102 for the non supplemented group. At day 7 cell numbers for the calcium supplemented group and the non supplemented group were 1.8 × 104 ± 1.5 × 103 and 3.0 × 104 ± 7.3 × 103 cells, respectively. At day 10, the supplemented and non supplemented groups had 8.1 × 104 ± 2.0 × 103 and 8.4 × 104 ± 1.4 × 103cells, respectively.

Figure 5.

Proliferation of hMSCs seeded in tissue culture-treated polystyrene in medium containing 5mM CaCO3 or no CaCO3 supplement, exhibiting no significant differences in cell number during a 10 day incubation period.

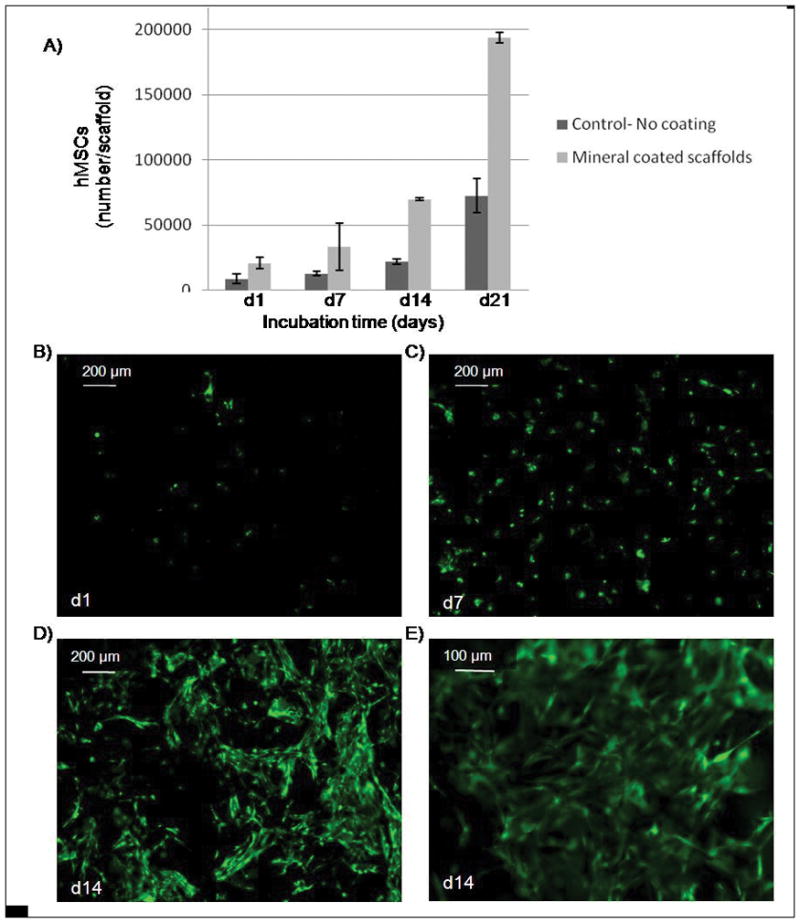

Human MSCs attached and proliferated when seeded either on the surface of the mineral layer grown on alginate scaffolds or on the surface of scaffolds with no mineral coating during the 21 day incubation period evaluated. The number of hMSCs was significantly higher in the mineral-coated group at each time point during the incubation period. In the mineral-coated group, hMSCs showed a well-spread morphology after 14 days of incubation and a rounded morphology at earlier time points (Fig. 4E). The number of hMSCs on mineral-coated scaffolds significantly increased at all time points after day 7 (p <0.05 in all groups). (Fig. 4A–D). There was no significant difference between day 1 and day 7 (p=0.1). However, between day 14 (7×104 ±1.0×103 cells) and day 21 (1.9×105 ±4.2×103 cells) the number of hMSCs showed a pronounced increase compared to earlier time points (Fig. 4A). In the non coated group, the increase in cell number at the earlier time points (d1 and d7) was not significant (p=0.08). As the incubation period increased, cell number significantly increased (p<0.05, for each group), but did not approach the cell number observed on mineral-coated substrates.

Regulation of mineral nucleation

Mineral could be nucleated and grown on the surface or in the interior of the alginate scaffolds, depending on the material processing conditions. Outer surface mineralization was observed in all experiments performed as confirmed by SEM and μ-CT analysis (Fig. 2A–D, Fig. 9A). In scaffolds prepared with 1mm channels (Fig. 7B–D), mineral nucleation and growth was also observed on the surface of the inner channels (Fig. 7E–G) but not within the macroporous interior of the scaffolds. Alginate scaffolds incubated in mSBF using the system designed to “force” the mSBF solution into the scaffold interior (Fig. 8A) showed evidence of mineral nucleation and growth on inner pore surfaces as well as outer scaffold surfaces (Fig. 8D–E). Elemental analysis of the mineral via energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) demonstrated the nucleation of a calcium- and phosphorous-based mineral, and SEM fields of view containing non-continuous mineral had an average Ca/P ratio of 3.3 (Fig. 8F). However, it should be noted that SEM and EDS analysis of the mineral formed on the inner pore walls of the scaffolds likely also included calcium-crosslinked alginate, which may contribute to the relatively high Ca/P ratio measured. μ-CT analysis demonstrated that the mineral nucleated in the scaffolds exposed to the forced fluid system appeared to be continuous through the thickness of the scaffold (Fig. 9C–D).

Discussion

Incubation of alginate scaffolds in mSBF resulted in gradual nucleation and growth of a continuous mineral layer with a morphology consistent with hydroxyapatite. The extent of heterogeneous mineral nucleation is enhanced by prolonged incubation periods (Fig. 2A–D), likely resulting from the interaction between the carboxylic acid groups present in alginate and the ionic constituents in mSBF solution. It has been widely reported that carboxylic acid groups are involved in directing nucleation of calcium-based minerals 9,17,18. There was no evidence of mineral nucleation in our control group (Fig. 2E), which consisted of samples incubated in a solution that contained calcium ions but did not contain phosphate ions. An additional control experiment in which scaffolds were incubated in mSBF solution with no calcium or phosphate resulted in almost immediate degradation of the scaffolds (data not shown), which is not surprising since the mechanism of alginate degradation involves solubilization via the loss of calcium ions into solution. The HAP mineral nucleated on the alginate scaffolds displayed primarily a spherulitic morphology on the micrometer-scale and a plate-like morphology on the nanometer scale (Fig. 2F). The micro-scale spheres exhibit varying diameters, consistent with radial crystal growth initiating at a central seed 17. Therefore, smaller spheres likely represent crystals that have recently nucleated and the larger spheres represent crystals that have grown for longer periods of time. The plate-like morphology observed on the nanometer scale is similar to the structure of natural bone apatite 26.

The mineral nucleated on alginate scaffolds had a composition consistent with natural bone apatite. The Ca/P ratio of the mineral nucleated on the alginate scaffolds was 1.61 (Fig. 4A) which is slightly lower than stoichiometric HAP, 1.67. This result is expected, as the approach used for the mineral nucleation is designed to mimic the natural vertebrate biomineralization process. The apatites in vertebrate bone and enamel are not pure hydroxyapatite, they contain other ions, including CO32−, Cl−, Mg2+, Na+, and K+ 27. Small amounts of some of these ions (i.e. magnesium, sodium) can substitute for calcium ions in the crystal lattice resulting in a lower Ca/P ratio 6. Previous studies that have formed HAP coatings via mSBF incubation have similarly shown Ca/P ratios less than 1.679,28,29. X-ray diffraction spectra indicate that the mineral formed on alginate scaffolds has peaks associated with HAP, and the peaks are broad, which is indicative of poor crystallinity. Previous studies indicate that HAP coatings with lower crystallinity have a better potential for resorption in vivo 30 compared to pure, highly crystalline HAP, which resorbs very slowly if at all 31,32. Analysis of the mineral nucleated on the scaffolds was only performed at the longest time of incubation, but we assume the mineral characteristics are similar at all time points. One parameter that could result in a change of mineral characteristics at different time points is the mSBF pH. The pH of the mSBF solution was monitored daily for a period of 4 weeks and even though there were small fluctuations (pH 6.5–6.8) during the process there is no particular trend observed at different times during the process (Fig. S1). In addition, other polymeric materials have been incubated in mSBF in for shorter periods of time and the resulting mineral is a HAP phase consistent with the mineral grown in our current material9,28,29.

Mineral nucleation and growth on the outer surface of alginate scaffolds was more predominant, which can be attributed in part to a transport limitation. During the mSBF incubation process samples were continuously rotating not only to maintain a homogenous ionic distribution but also to promote fluid flow through the pores of the scaffolds, thereby promoting mineral nucleation on the interior pore walls. However, initial experiments demonstrated preferential mineral formation on the outer surface of alginate scaffolds (Fig. 2A–D), with no mineral nucleation observed on the inner pore walls (Fig. 2G). Examination of SEM images of earlier experiments show that while the cross-sections of alginate scaffolds were highly porous (Fig. 1B), the surfaces of the scaffolds were not highly porous (Fig. 3A–B). Therefore, we hypothesized that these “skin effects” resulting from the scaffold processing could be contributing to the preferential mineral nucleation on the outer scaffold surface. To address whether “skin effects” were indeed influencing the preferred nucleation mechanism, alginate samples were prepared with an additional surface treatment – a physical etching process that removed the outermost surfaces of the scaffold to reveal the porous interior (Fig. 3C). Samples with or without this surface treatment were then incubated in mSBF for 4 weeks. No evidence of mineral nucleation was observed in the interior of surface-treated samples (Fig. 3D), indicating that the hypothesized “skin effect” was not the primary reason for poor mineral nucleation on inner pore walls. Detailed characterization of the porosity of the scaffolds was not performed in this work, but Shapiro et al. and Lin et al. have previously characterized porosity of alginate scaffolds fabricated using the same technique 19,24.

We further explored preferential mineral nucleation on the outer surface of alginate scaffolds by creating samples with millimeter-scale channels and incubating these scaffolds in mSBF. Mineral coating was observed on the outer scaffold surface and on the inner surfaces of the millimeter scaled channels (Fig 7E–G). Although preferential mineral formation on the exterior surfaces of a scaffold may not be ideal for creation of a true organic-inorganic composite structure, it could be advantageous for applications that would benefit from mineral nucleation only in particular regions within a scaffold. Examples may include tissue engineering at bone-soft tissue interfaces and templated growth of extended, continuous mineral layers.

Importantly, mineral could also be induced to nucleate and grow on inner pore walls of alginate scaffolds in specific experimental conditions. A custom-made system was developed to hold the alginate scaffolds fixed while fluid was forced to flow through the scaffold pores (Fig. 8A–B) This approach resulted in mineral nucleation on inner pore walls; however, based on SEM analysis mineral nucleation was not as extensive as that observed on the outer scaffold surface (Fig. 8D–E). Elemental analysis of the mineral via EDS analysis showed calcium and phosphorous peaks, with a Ca/P ratio of 3.3 (Fig. 8F). Since the mineral layer in the interior was not continuous, the EDS analysis could possibly have detected both the calcium ions from the mineral and also crosslinking calcium ions, which could explain the relatively high Ca/P ratio. Mineral formed on porous materials is often discontinuous through the thickness of the scaffold, but in this study we demonstrate that the mineral nucleation was continuous throughout the thickness of the scaffolds when using the forced fluid system (Fig. 9B–D) Taken together, these data suggest that preferential mineral nucleation observed on the outer surface of alginate scaffolds was caused by differences in ion concentrations in the interior of scaffolds when compared to the exterior solution due to transport limitations, as forcing fluid through the alginate scaffolds resulted in mineral nucleation throughout the macropores of the material. Other systems, have been successfully developed to achieve uniform 3D coatings such as a filtration system by Segvich et al which also forces the fluid through scaffolds with macropores (425–600 μm in diameter)33. Using the system we developed, 3D mineral nucleation is achieved in scaffolds with smaller pores (200μm diameter approximately).

Human MSCs attached and proliferated when cultured on alginate scaffolds coated with a HAP layer. Cells in contact with the mineral surface first attach, adhere and spread. Morphology of hMSCs in our study exhibit a rounded morphology at earlier time points (day 1 and day 7) but gradually they spread out over the HAP-coated alginate samples and displayed well-spread morphology (day 14 and day 21) consistent with previous literature 34. The growth rate of hMSCs in this system was slower compared to hMSCs seeded in monolayer cultured on tissue culture-treated polystyrene (Fig. 5), since by day 7 hMSCS cultured on tissue culture-treated polystyrene underwent 3 doublings compared to 1 doubling in the mineral-coated alginate scaffolds group at the same time point. The decreased growth rate in the scaffolds versus tissue culture-treated polystyrene is consistent with a previous study in which murine-derived adipose tissue stromal cells (ATSCs) were encapsulated in alginate microcapsules and their cell number doubled between day 1 and day 7, which is similar to our findings 20. The difference in hMSCs number on mineral-coated versus non-coated scaffolds can be primarily attributed to an enhanced initial cell attachment. Both coated and non-coated alginate groups were seeded with the same total number of cells, but in the mineral-coated group the cell number at day 1 was twice as high when compared to the non coated group, and hMSCs on both the coated and non-coated scaffolds underwent 3 doublings during the incubation period. The observed increase in hMSCs attachment is an important advantage of the mineral coating, since cell attachment is important for the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of multiple cell types including bone-forming cells.

Although it has been reported that high calcium concentration (≥10mM) can be cytotoxic to osteoblasts 35, we observed no negative effect on the morphology, viability and proliferation of hMSCs on HAP surfaces in medium containing 5mM calcium when compared to typical hMSCs culture (Fig. 5). Slightly elevated Ca 2+ concentrations (2–6mM) have been shown to stimulate osteoblast proliferation, higher concentrations (6–10mM) may stimulate differentiation, and Ca2+ above 10mM may abrogate osteoblast survival 35. Therefore, although this study examined only hMSCs morphology and increases in cell number over time, future studies with these materials may reveal significant effects of calcium on behavior of primary osteoblasts or hMSCs-derived osteoblasts. Other material properties, such as topographical features, may have also influenced the interaction between hMSCs and the mineral layer grown on the alginate scaffold. Surface topography has been shown to influence various activities of osteoblasts and MSCs, such as differentiation, proliferation, and matrix production 36–38.

Although the current study focused on controlling mineral nucleation and characterizing preliminary stem cell attachment and growth, it is possible that HAP-coated alginate scaffolds may be used to promote osteoinductivity as well as osteoconductivity. Recent studies suggest that HAP-based materials may intrinsically promote ectopic bone formation in vivo, even without inclusion of exogenous cells or growth factors 39,40. In addition, our observation that hMSCs attach and proliferate on HAP-coated alginate scaffolds suggests that these materials may serve as appropriate carriers for hMSCs in emerging cell-based bone tissue engineering applications. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that HAP substrates may have a positive influence on osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs in vitro 34 and in vivo 41–43. Furthermore, the HAP coatings created here may be useful as carriers for delivery of proteins or peptides, such as bone growth factors. Calcium phosphate biomaterials have a high affinity for proteins, and we and others have recently used this binding affinity as a mechanism for sustained protein release from biomaterials 28,44. Further studies will be required to demonstrate the ability of these scaffold materials to serve as carriers for cell and protein delivery in osteoinductive bone tissue engineering applications.

Conclusion

In this study we developed macroporous, HAP-coated alginate scaffolds using a biomimetic approach. Mineral growth was observed on the outer surfaces of alginate scaffolds in all processing conditions, and could also be achieved on the inner pore walls of the scaffolds in particular processing conditions. The scaffolds had a mineral phase, composition, and morphology similar to that of vertebrate bone tissue, which suggests that these coatings may interact favorably with bone-forming cells. Preliminary experiments demonstrate that the HAP coatings support attachment and proliferation of hMSCs, which maintain a well-spread morphology similar to their morphology in standard cell culture conditions. Our results suggest that the scaffolds described here may ultimately be used in bone tissue engineering applications as a scaffold material to deliver stem cells, and perhaps also biologically active molecules.

Supplementary Material

Figure 6.

A) hMSCs seeded on mineralized alginate scaffolds showed better initial attachment during the 21 day period of incubation. Cell number was determined using cell titer blue assays, which measures cellular metabolic activity. (B–E) Fluorescent photomicrographs of hMSCs stained with Calcein AM (green, indicates esterase activity in viable cells) after B) 1 day, C) 7 days, D) 14 days. C) hMSCs cultured for 14 day exhibit a well-spread morphology.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge technical assistance from Ron McCabe in the design and fabrication of the sample holders for the “forced” mineralization experiments and the lid for the preparation of the samples with channels. We would also like to acknowledge James Molenda for assistance with the biological characterization work. The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (R03AR052893) and a pre doctoral fellowship from the Harriet Jenkins Pre-Doctoral Fellowship Program (DS).

References

- 1.Burg KJ, Porter S, Kellam JF. Biomaterial developments for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2000;21(23):2347–59. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornell CN. Osteoconductive materials and their role as substitutes for autogenous bone grafts. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30(4):591–8. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutmacher DW. Scaffolds in tissue engineering bone and cartilage. Biomaterials. 2000;21(24):2529–43. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Ma PX. Polymeric scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32(3):477–86. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017544.36001.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zapanta LeGeros R. Properties of Osteoconductive Biomaterials: Calcium Phosphates. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2002;(395):81–98. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habibovic P. Biomimetic Hydroxyapatite Coating on Metal Implants. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2002;85(3):517–522. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokubo T, Kushitani H, Sakka S, Kitsugi T, Yamamuro T. Solutions able to reproduce in vivo surface-structure changes in bioactive glass-ceramic A-W. J Biomed Mater Res. 1990;24(6):721–34. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820240607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P, Ohtsuki C, Kokubo T, Nakanishi K, Soga N, Nakamura T, Yamamuro T. Apatite Formation Induced by Silica Gel in a Simulated Body Fluid. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 1992;75(8):2094–2097. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy WL, Mooney DJ. Bioinspired growth of crystalline carbonate apatite on biodegradable polymer substrata. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(9):1910–7. doi: 10.1021/ja012433n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang R, Ma PX. Biomimetic polymer/apatite composite scaffolds for mineralized tissue engineering. Macromol Biosci. 2004;4(2):100–11. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Ni M, Zhang M, Ratner B. Calcium phosphate-chitosan composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2003;9(2):337–45. doi: 10.1089/107632703764664800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsui YC, Doyle C, Clyne TW. Plasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium substrates. Part 1: Mechanical properties and residual stress levels. Biomaterials. 1998;19(22):2015–29. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CK, Lin JH, Ju CP, Ong HC, Chang RP. Structural characterization of pulsed laser-deposited hydroxyapatite film on titanium substrate. Biomaterials. 1997;18(20):1331–8. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhitomirsky I, Gal-Or L. Electrophoretic deposition of hydroxyapatite. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 1997;8(4):213–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1018587623231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy WL, Kohn DH, Mooney DJ. Growth of continuous bonelike mineral within porous poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50(1):50–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<50::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy WL, Simmons CA, Kaigler D, Mooney DJ. Bone regeneration via a mineral substrate and induced angiogenesis. J Dent Res. 2004;83(3):204–10. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grassmann O, Lobmann P. Biomimetic nucleation and growth of CaCO3 in hydrogels incorporating carboxylate groups. Biomaterials. 2004;25(2):277–82. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nancollas GH. Biomineralization mechanisms: a kinetics and interfacial energy approach. Journal of Crystal Growth. 2000;211:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin HR, Yeh YJ. Porous alginate/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: preparation, characterization, and in vitro studies. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;71(1):52–65. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbah SA, Lu WW, Chan D, Cheung KM, Liu WG, Zhao F, Li ZY, Leong JC, Luk KD. In vitro evaluation of alginate encapsulated adipose-tissue stromal cells for use as injectable bone graft substitute. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347(1):185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashton RS, Banerjee A, Punyani S, Schaffer DV, Kane RS. Scaffolds based on degradable alginate hydrogels and poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres for stem cell culture. Biomaterials. 2007;28(36):5518–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Ramay HR, Hauch KD, Xiao D, Zhang M. Chitosan-alginate hybrid scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26(18):3919–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruder SP, Fink DJ, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells in bone development, bone repair, and skeletal regeneration therapy. J Cell Biochem. 1994;56(3):283–94. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240560809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro L, Cohen S. Novel alginate sponges for cell culture and transplantation. Biomaterials. 1997;18(8):583–90. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(96)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morejón-Alonsoa L. Effect of Sterilization on the Properties of CDHA-OCP-β-TCP Biomaterial. Materials Research. 2007;10(1):15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilezikian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan GA. Principles of Bone Biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeGeros RZ. Properties of osteoconductive biomaterials: calcium phosphates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(395):81–98. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jongpaiboonkit L, Franklin-Ford T, Murphy WL. Advanced Materials. 2008. Mineral-coated, biodegradable microspheres for controlled protein binding and release. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weng J, Liu Q, Wolke JG, Zhang X, de Groot K. Formation and characteristics of the apatite layer on plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings in simulated body fluid. Biomaterials. 1997;18(15):1027–35. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ducheyne P, Radin S, King L. The effect of calcium phosphate ceramic composition and structure on in vitro behavior. I. Dissolution. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27(1):25–34. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi K, Hirano T, Yoshida G, Iwasaki K. Degradation-resistant character of synthetic hydroxyapatite blocks filled in bone defects. Biomaterials. 1995;16(13):983–5. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)94905-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahan KT, Carey MJ. Hydroxyapatite as a bone substitute. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89(8):392–7. doi: 10.7547/87507315-89-8-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segvich S, Smith HC, Luong LN, Kohn DH. Uniform deposition of protein incorporated mineral layer on three-dimensional porous polymer scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;84(2):340–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toquet J, Rohanizadeh R, Guicheux J, Couillaud S, Passuti N, Daculsi G, Heymann D. Osteogenic potential in vitro of human bone marrow cells cultured on macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate ceramic. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;44(1):98–108. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199901)44:1<98::aid-jbm11>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maeno S, Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Morioka H, Yatabe T, Funayama A, Toyama Y, Taguchi T, Tanaka J. The effect of calcium ion concentration on osteoblast viability, proliferation and differentiation in monolayer and 3D culture. Biomaterials. 2005;26(23):4847–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kieswetter K, Schwartz Z, Hummert TW, Cochran DL, Simpson J, Dean DD, Boyan BD. Surface roughness modulates the local production of growth factors and cytokines by osteoblast-like MG-63 cells. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;32(1):55–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199609)32:1<55::AID-JBM7>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deligianni DD, Katsala N, Ladas S, Sotiropoulou D, Amedee J, Missirlis YF. Effect of surface roughness of the titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V on human bone marrow cell response and on protein adsorption. Biomaterials. 2001;22(11):1241–51. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Von Recum A, Shannon CE, Cannon CE, Long KJ, Van Kooten TG, Meyle J. Surface Roughness, Porosity, and Texture as Modifiers of Cellular Adhesion. Tissue Eng. 1996;2(4):241–253. doi: 10.1089/ten.1996.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fellah BH, Gauthier O, Weiss P, Chappard D, Layrolle P. Osteogenicity of biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics and bone autograft in a goat model. Biomaterials. 2008;29(9):1177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Habibovic P, Kruyt MC, Juhl MV, Clyens S, Martinetti R, Dolcini L, Theilgaard N, van Blitterswijk CA. Comparative in vivo study of six hydroxyapatite-based bone graft substitutes. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(10):1363–70. doi: 10.1002/jor.20648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruder SP, Kurth AA, Shea M, Hayes WC, Jaiswal N, Kadiyala S. Bone regeneration by implantation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1998;16(2):155–62. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arinzeh TL, Peter SJ, Archambault MP, van den Bos C, Gordon S, Kraus K, Smith A, Kadiyala S. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells regenerate bone in a critical-sized canine segmental defect. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(10):1927–35. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohgushi H, Okumura M, Tamai S, Shors EC, Caplan AI. Marrow cell induced osteogenesis in porous hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate: a comparative histomorphometric study of ectopic bone formation. J Biomed Mater Res. 1990;24(12):1563–70. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820241202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsumoto T, Okazaki M, Inoue M, Yamaguchi S, Kusunose T, Toyonaga T, Hamada Y, Takahashi J. Hydroxyapatite particles as a controlled release carrier of protein. Biomaterials. 2004;25(17):3807–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.