Abstract

MeCP2 is a methyl-DNA binding transcriptional regulator that contributes to the development and function of CNS synapses; however the requirement for MeCP2 in stimulus-regulated behavioral plasticity is not fully understood. Here we show that acute viral manipulation of MeCP2 expression in the Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) bidirectionally modulates amphetamine (AMPH)-induced conditioned place preference. Hypomorphic Mecp2 mutant mice have an increased number of NAc GABAergic synapses and show deficient AMPH-induced structural plasticity of NAc dendritic spines. Furthermore these mice show deficient plasticity of striatal immediate early gene inducibility following repeated AMPH administration. Intriguingly, psychostimulants induce phosphorylation of MeCP2 at Ser421, a site that regulates MeCP2's function as a repressor. Phosphorylation is selectively induced in GABAergic interneurons of the NAc, and its extent strongly predicts the degree of behavioral sensitization. These data reveal novel roles for MeCP2 in both mesolimbocortical circuit development and in the regulation of psychostimulant-induced behaviors.

Drugs of abuse drive changes in behavior by altering the function and plasticity of reward-related circuits in brain1. The mesolimbocortical dopamine (DA) circuit is comprised of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and their synaptic targets in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), frontal cortex, and associated limbic structures. Repeated psychostimulant exposure produces changes in both functional and structural plasticity of synapses in the striatum2-4, and these alterations are thought to contribute to the expression of behavioral sensitization and conditioned place preference (CPP). Considerable evidence suggests that this process depends upon the regulated transcription of new gene products5,6. Psychostimulant-activated signaling pathways converge in the NAc to regulate the activity and/or expression of a number of transcriptional regulators (i.e. ΔFosB, MEF2, and NF-κB) that subsequently modulate synapses6-10.

Loss-of-function mutations in the methyl-DNA binding transcriptional regulator Methyl CpG-binding Protein 2 (MeCP2) cause the neurodevelopmental disorder Rett Syndrome (RTT)11. The onset of RTT symptoms coincides with the time-period during postnatal development when sensory-driven neuronal activity is required for refinement of cortical circuitry, suggesting that RTT may have a synaptic pathophysiology11. A variety of developmental synaptic abnormalities have been detected in Mecp2 null mice including decreases in the number of hippocampal glutamatergic synapses12, shifts in the balance between excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in somatosensory cortex13, and an extended period of visual cortical plasticity14. However evidence suggests that MeCP2 also contributes to the function and plasticity of mature neurons. For example, Cre-mediated recombination of a conditional Mecp2 allele in cultured neurons after synaptogenesis induces an acute decrease in mini-EPSC frequency that mimics the effects of the Mecp2 null mutation15. Furthermore, conditional re-expression of MeCP2 in Mecp2 null neurons after birth significantly delays neurological symptoms and prolong lifespan, suggesting that these phenotypes arise at least in part from the lack of MeCP2 expression in mature neurons16. Hypomorphic mutations in Mecp2 are associated with limited motor phenotypes17,18, thereby rendering these mice suitable for broader behavioral analyses. Previous studies have demonstrated that mutant alleles of Mecp2 are associated with changes in anxiety, altered social interactions, and certain impairments in learning and memory17-21. However the mechanisms by which MeCP2 influences these behaviors, and whether they arise as a result of developmental abnormalities or functions of MeCP2 in the mature brain, have remained largely unexplored.

MeCP2 is rapidly phosphorylated at Ser421 (pMeCP2) in response to synaptic activity suggesting a stimulus-dependent mechanism of MeCP2 regulation22. In the absence of synaptic activity, MeCP2 binds to and is required for repression of promoter IV in the gene encoding Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), an activity-inducible secreted protein that exerts numerous effects on synaptic function23,24. Overexpression of a nonphosphorylatable Ser421Ala mutant MeCP2 inhibits activity-dependent expression of Bdnf exon IV, indicating that phosphorylation at this site is required for dynamic derepression of Bdnf22. These data are significant because they demonstrate that Ser421 phosphorylation modulates the ability of MeCP2 to act as a transcriptional repressor, suggesting that this phosphorylation event can be used as a surrogate measure of changes in the functional state of MeCP2-dependent transcriptional pathways in vivo.

Here we have investigated whether MeCP2 may contribute to psychostimulant-regulated behaviors. We find that acute viral-mediated knockdown of MeCP2 in adult NAc enhances AMPH-induced CPP whereas MeCP2 overexpression reduces CPP, suggesting that MeCP2 acts to limit the rewarding properties of psychostimulants. In a strain of mice bearing a hypomorphic mutation in Mecp2, we find altered behavioral responses to acute and repeated AMPH treatment and we identify changes in both the development and plasticity of striatal synapses. Finally we show that psychostimulants lead to rapid, DA-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2 in NAc GABAergic interneurons. Together these data define novel roles for MeCP2 in the development and function of the mesolimbocortical DA circuit, and they raise the possibility that AMPH-induced alterations in striatal GABAergic interneuron function may contribute to behavioral adaptations to psychostimulants.

Results

MeCP2 modulates AMPH-induced behaviors

To determine whether MeCP2 in adult brain is required for AMPH-induced behaviors, we injected lentivirus into the NAc to induce shRNA-mediated knockdown or overexpression of MeCP2 in C57BL6/J mice (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). Compared with mice expressing a control scrambled shRNA (SCR), locomotor activities were significantly enhanced in mice expressing the shRNA against MeCP2 following acute administration of 3 mg/kg AMPH (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. 1b). Repeated AMPH injection over 5 consecutive days drove a progressive increase in locomotor activity in both SCR- and MeCP2 shRNA-expressing mice. However on each day the locomotor activities of the MeCP2 shRNA-expressing mice were greater than those of controls (Fig. 1e). In AMPH-induced CPP, control SCR infected mice showed dose-dependence, displaying preference for the chamber paired with 3 mg/kg but not with 1mg/kg AMPH (Fig. 1f). By contrast MeCP2 shRNA-expressing mice showed a significant preference for the AMPH-paired chamber at both doses, suggesting that reducing expression of MeCP2 in the NAc increases the rewarding properties of AMPH (Fig. 1e). Consistent with this interpretation, overexpression of MeCP2 in the NAc (Fig. 1g–j) eliminated preference for the 3mg/kg AMPH-paired chamber (Fig. 1k). Collectively these data suggest that MeCP2 in the NAc may function to limit the rewarding properties of AMPH.

Figure 1. Local lentiviral regulation of MeCP2 in the NAc alters AMPH-induced behaviors.

a–f, Lentiviral shRNA knockdown of MeCP2. a, GFP expression in NAc 20 days post-injection. b–d, enlarged area in panel a. Open arrowheads indicate the absence of MeCP2 expression in GFP-expressing cells. e, 7-9 days after infection with an shRNA targeting MeCP2 (n=12) or a control scrambled shRNA (SCR, n=14), mice were administered 3mg/kg AMPH and placed into the open field for 5 consecutive days. RMANOVA showed a significant effect of treatment (F1,24=8.95, p=0.006) and days (F4,96=23.4, p<0.0001). * - ps<0.05, pair-wise comparisons between groups. f, Seven days after bilateral intra-NAc stereotactic injection of scrambled (SCR) or MeCP2 shRNA virus, C57BL/6 mice (n=7-8/group) received six alternate pairings of AMPH (1mg/kg or 3mg/kg) or Veh in the CPP apparatus as described. ANOVA revealed a significant dose by treatment interaction (F1,28=5.6, p=0.026; * - p=0.018, shRNA-MeCP2 compared to shRNA-SCR at 1mg/kg AMPH). g–k, Lentiviral overexpression of MeCP2 in the NAc. g, GFP expression 20 days post-injection; h–j, enlarged area in panel g. Filled arrowheads indicate the enhanced expression of MeCP2 in GFP-expressing cells. k, 7-9 days after infection with lenti-GFP (n=8) or lenti-MeCP2 (n=8), mice were tested for CPP with 3 pairings of 3mg/kg AMPH as described. RMANOVA revealed a significant chamber-preference by treatment interaction (lenti-GFP compared with lenti-MeCP2) (F1,13=5.47, p=0.036); * - p=0.01, time in AMPH chamber compared to that in Veh chamber within lenti-GFP treated mice. Scale bars indicate 30μm. Results displayed as mean ± s.e.m.

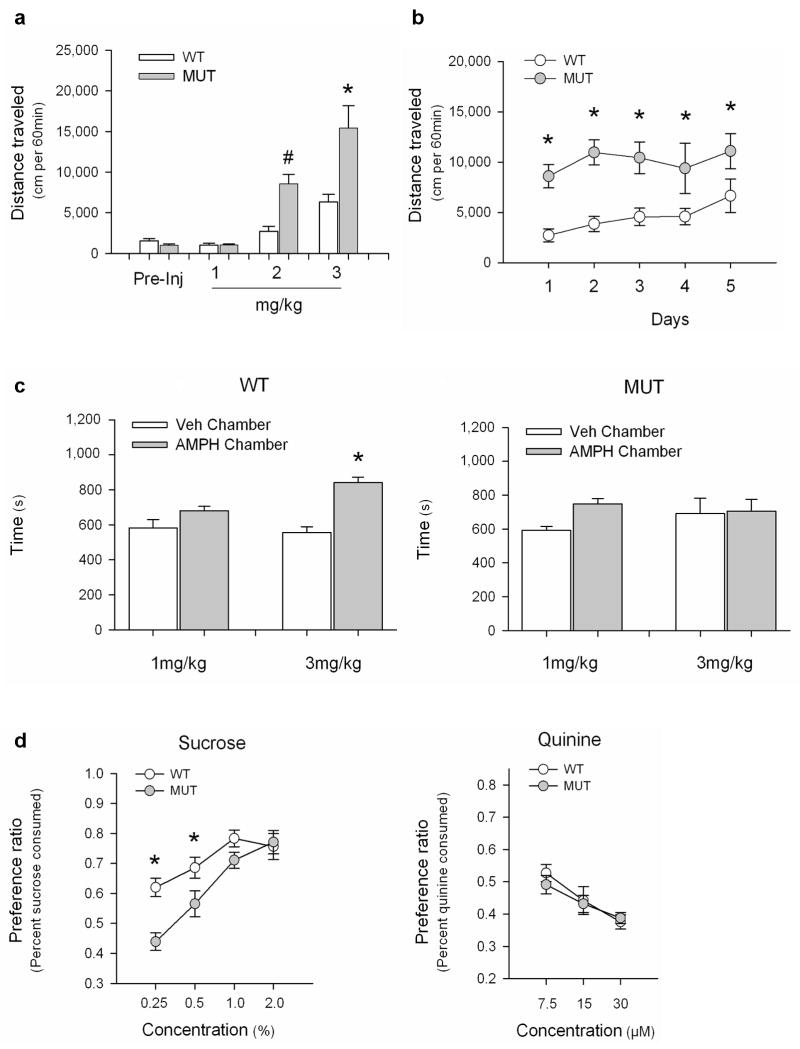

We next examined locomotor responses to AMPH in mice bearing a hypomorphic mutation in Mecp2 (Mecp2308)17. These mice express a C-terminally truncated form of MeCP2 and display a mild version of the neurological phenotypes observed in Mecp2 null mice25. In the open field, there were no significant differences in baseline locomotor activities between the Mecp2308/y mutant (MUT) mice and their Mecp2+/y wildtype (WT) littermates (Fig. 2a). Both MUT and WT mice had enhanced locomotor activities following acute AMPH administration, however the MUT mice responded more robustly than WT mice to 2 and 3 mg/kg AMPH (Fig. 2a). Repeated daily injection of 2mg/kg AMPH over 5 consecutive days drove a progressive increase in locomotion in the WT mice. However no significant enhancement was detected in MUT mice over the same period (Fig. 2b). MUT mice also failed to show enhanced locomotion following repeated AMPH administration when mice were injected with 3mg/kg AMPH for 5 consecutive days in their home cages then challenged with AMPH or vehicle (Veh) in the open field after a 7 day period of withdrawal (Supplementary Fig. 2). It is possible that the elevated acute locomotor activity in the MUT mice precludes further enhancement upon repeated AMPH administration. However locomotor activity of MUT mice following acute administration of 3mg/kg AMPH (Fig. 2a) was significantly greater than activity following repeated exposure to 2mg/kg AMPH (Fig. 2b), raising the alternative possibility that mechanisms of locomotor sensitization may be impaired by the Mecp2308 mutation. Importantly, although local viral knockdown of Mecp2 in the NAc phenocopied the enhanced locomotor response to acute AMPH seen in the MUT mice, the virally injected mice showed normal locomotor sensitization to repeated AMPH injection (Fig. 1e). Since the Mecp2308 mutation is constitutive, differences between these datasets raise the possibility that MeCP2 may contribute to psychostimulant-regulated behaviors not only through its actions in the adult NAc, but also via its actions during development and/or in other adult brain regions.

Figure 2. Mecp2308/y mutant mice show altered AMPH-induced behaviors.

a, AMPH-induced open field locomotion in Mecp2+/y (WT) and Mecp2308/y (MUT) littermates. (F7,53=20.03, p < 0.001; * - p<0.001, WT compared to MUT for 3mg/kg; # - p=0.019, WT compared to MUT for 2mg/kg). b, Open field locomotor activity induced by repeated 2mg/kg AMPH. By RMANOVA the within subject effect of days and the day by genotype interaction were not significant. However, the between subjects effect of genotype was significant (F1, 14 =14.96, p<0.002; * - ps<0.05, MUT compared to WT). By RMANOVA within each genotype, the days effect was significant for WT (F4,28=5.115, p<0.003), but not for MUT (F4,28=0.609; p=0.659). c, CPP in Mecp2308 mice (n=9/genotype for 1mg/kg; n=12/genotype for 3mg/kg). For WT, RMANOVA found a significant preference for the AMPH-paired chamber at 3mg/kg (chamber by dose: F1,18=4.29, p=0.05); * - p < 0.001, Veh- compared to AMPH-paired chamber). In MUT, there was no significant main effect of dose (F1,20=1.45, p=0.24) or chamber preference (F1,20=1.05, p= 0,32) and the chamber by dose interaction was not significant (F1,20=0.50, p=0.49). d, Sucrose preference test in Mecp2+/y (WT) and Mecp2308/y (MUT) littermates (n=9 mice/group). For sucrose, RMANOVA showed significant main effects of concentration (F3,48=19.75, p<0.0001) and genotype (F1,16=12.88, p=0.002), and a significant concentration by genotype interaction (F3,14=2.78, p=0.051). * - ps<0.05, WT compared to MUT at 0.25% and 0.5%. p=0.079, WT compared to MUT at 1.0%. For quinine, RMANOVA revealed a main effect of concentration (F2,34=12.52, p=0.001), but no genotype effect. Results displayed as mean ± s.e.m.

Finally, to determine whether the Mecp2308 mutation affects the rewarding properties of AMPH, we tested Mecp2+/y WT and Mecp2308/y MUT mice in CPP. WT mice showed a dose-dependent increase in CPP, displaying a significant preference for a chamber paired with 3mg/kg AMPH, but not with 1mg/kg AMPH (Fig. 2c). By contrast, MUT mice demonstrated no significant preference for the drug-paired chamber at either dose. Their failure to show CPP could arise either from impaired reward processing or from contextual learning deficits. As a learning-independent measure of reward, we assessed sucrose preference in the Mecp2308 mice. Both WT and MUT mice preferred sucrose over water with increasing sucrose concentrations (Fig 2d). However MUT animals had a significantly lower preference for sucrose than WT mice at low sucrose concentrations. By contrast WT and MUT mice showed similar responses to a series of quinine concentrations. Although sucrose preference is an indirect measure of reward valuation, it does not permit us to exclude the possibility that contextual learning deficits may contribute to impaired CPP in the Mecp2308/y mice. Nonetheless, both the sucrose-preference and CPP results suggest that the Mecp2308 mutation impairs reward processing, whereas local knockdown of Mecp2 in the NAc of adult mice enhances reward. Results from both experiments indicate that MeCP2 makes important functional contributions to reward-related behaviors. However, similar to the sensitization data above, they raise the possibility that MeCP2 may differentially control these behaviors through its actions at different times in development and/or in different regions of the brain.

Altered NAc synapses in Mecp2 mutant mice

Synaptic connections in the NAc represent a target of psychostimulant-induced plasticity26,27. To determine whether synapses in the NAc are affected by the Mecp2308 mutation, we immunostained coronal brain sections through the NAc of Mecp2+/y WT and Mecp2308/y MUT mice with antibodies against presynaptic markers for both GABAergic (VGAT, GAD65) and glutamatergic (VGLUT1) synapses. We observed an significant increase in the overall intensities of VGAT and GAD65 immunoreactivities in the NAc of MUT compared with WT mice, and a similar increase in numbers of VGAT or GAD65 positive punctae (Fig. 3a,b,d,e,g,h,j,k). No differences between WT and MUT mice were detected in the intensities of VGLUT1 staining or in the numbers of VGLUT1-positive punctae (Fig. 3c,f,i,l). These data show that MeCP2 is important for establishing the number of GABAergic synapses in the NAc, which may subsequently affect behavioral responses to psychostimulants.

Figure 3. Mecp2308/y MUT mice show altered GABAergic synaptic densities in the NAc.

a-f, Immunofluorescent labeling of presynaptic markers for GABAergic (GAD65 and VGAT) and glutamatergic (VGLUT1) synapses in coronal sections through the NAc from Mecp2+/y WT and Mecp2308/y MUT mice (n=4-5/group). Scale bar indicates 10μm. g–l, Quantitation of overall intensities of synaptic protein expression and numbers of synaptic punctae. g,j, Increased expression of GAD65 in MUT compared with WT littermates: intensity (F1,8=14.18, * - p=0.007), number of punctae (F1,8=10.36, * - p=0.015). h,k, VGAT immunofluorescence shows increased expression in MUT versus WT: intensity (F1,8=8.33, * - p=0.023), number of punctae (F1,8=8.33, * - p=0.023). i,l, VGLUT1 shows no significant change in expression by genotype. Results displayed as mean ± s.e.m.

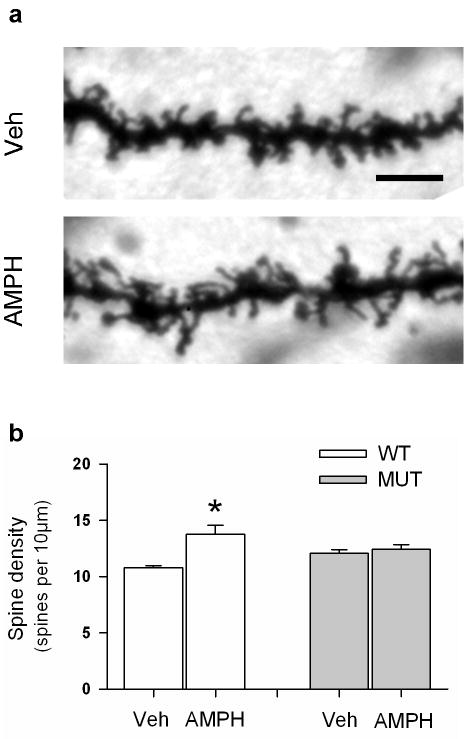

Repeated treatment with AMPH increases the density of dendritic spines on medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in the NAc2. These spines are sites of cortical glutamatergic synaptic contacts, and long-lasting changes in spine number are hypothesized to contribute to persistent behavioral adaptations following chronic psychostimulant treatment7,9. To determine whether the Mecp2308 mutation affects this structural plasticity, we treated WT or MUT mice with Veh or 3mg/kg AMPH for 21 consecutive days, and then processed the brains for Golgi–Cox staining. There were no differences between the dendritic spine densities of Veh-treated WT and MUT mice (Fig.4b), which is consistent with our VGLUT1 staining (Fig. 3c,f,i,j) and further indicates that basal numbers of NAc glutamatergic synapses are not affected by the Mecp2308 mutation. By comparison, chronic AMPH treatment induces an increase in spine densities in WT animals relative to their Veh controls (Fig. 4a,b). By contrast, spine densities were not enhanced in AMPH-treated MUT mice compared with their Veh controls (Fig. 4b), indicating a failure of this form of structural synaptic plasticity in the Mecp2308/y MUT mice.

Figure 4. Chronic treatment with AMPH fails to increase dendritic spine density in Mecp2 MUT mice.

MeCP2 MUT mice and their WT littermates were treated with Veh or AMPH (3mg/kg; i.p.) for 21 days. One day after the last injection, mice were perfused transcardially, and the brains were processed for Golgi-Cox staining. a. Representative images of dendrites from WT littermates treated with Veh or AMPH. Scale bar indicates 5μm. b. Quantitation of overall spine density per 10μm. Two-way ANOVA indicates a significant overall treatment effect (F3,14=8.33, p=0.015) and a significant genotype by treatment interaction (F3,14=4.85, p=0.05); * - p=0.01 WT treated with Veh compared to WT treated with AMPH. Results displayed as mean ± s.e.m.

AMPH-inducible gene expression in Mecp2 mutant mice

To investigate the consequences of the Mecp2 mutation on regulation of gene expression programs, we quantified Immediate Early Gene (IEG) expression in the NAc of Mecp2+/y WT and Mecp2308/y MUT mice following acute or repeated AMPH exposure. Following acute injection, both genotypes showed similar levels of c-Fos expression to Veh and to AMPH treatments (Fig. 5a,b,e; Supplementary Fig. 3). By contrast, AMPH-treated levels of FosB were reduced by more than half in MUT compared to WT mice (Fig. 5f,g,j), whereas AMPH-treated levels of JunB were elevated nearly 2-fold in MUT animals (Fig. 5h,i,k).

Figure 5. Mecp2 mutant mice show altered induction of Fos/Jun family IEGs.

a–d, c-Fos expression in the NAc of Mecp2+/y (WT) and Mecp2308/y (MUT) mice that received repeated Veh (Veh:AMPH) or AMPH (AMPH:AMPH) treatments and AMPH at challenge. Scale bar indicates 50μm. e, Quantitation of c-Fos expression as shown in panels a–d. ANOVA indicated a treatment by genotype effect (F3,26=4.36, p=0.048; * - p=0.006, Veh:AMPH-WT compared to AMPH:AMPH-WT; # - p=0.05, AMPH:AMPH-WT compared to AMPH:AMPH-MUT). c-Fos expression in MUT mice is not different between the Veh:AMPH and AMPH:AMPH conditions (p=0.90). f–i, FosB and JunB following acute AMPH challenge. Scale bar indicates 45 μm. j–k, Quantitations of FosB and JunB expression. j, In WT mice, FosB expression is reduced after repeated AMPH treatment (ANOVA; treatment by genotype: F3,23=11.01, p=0.003; * - p<0.001, Veh:AMPH-WT compared to AMPH:AMPH-WT). In MUT mice, the single injection of AMPH at challenge did not induce FosB expression as compared to WT animals ((x002C6) - p=0.001, Veh:AMPH-WT compared to Veh:AMPH-MUT), and there was no difference between the Veh:AMPH-MUT and AMPH:AMPH-MUT groups (p=0.96). k, Repeated injection of AMPH upregulates JunB expression in WT mice (ANOVA; treatment by genotype: F3,21 = 10.929, p=0.004; * - p=0.01, Veh:AMPH-WT compared to AMPH:AMPH-WT). For MUT animals acute AMPH injection at challenge caused JunB expression to be significantly elevated compared with similarly-treated WT mice (ˆ - p<0.001, Veh:AMPH-WT compared to Veh:AMPH-MUT); however, there was no statistical difference in JunB expression between the Veh:AMPH-MUT and AMPH:AMPH-MUT groups (p=0.47). Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

Chronic psychostimulant treatment has been shown to drive time-dependent changes in IEG inducibility6,28. To assess whether this plasticity is altered by the Mecp2308 mutation, we examined expression of c-Fos, FosB, and JunB in WT or MUT mice that had been given repeated injections of Veh or AMPH, withdrawn, and challenged with AMPH (see Supplementary Fig. 2). As previously reported6,28, we found that repeated AMPH administration (AMPH:AMPH) of Mepc2+/y WT mice led to persistent desensitization of c-Fos and FosB (Fig. 5a,c,e,f,j) but increased JunB induction (Fig. 5h,k) compared to Veh:AMPH treatment. By contrast, although these IEGs in Mecp2308/y MUT mice were induced by both single (Veh:AMPH) and multiple injections of AMPH (AMPH:AMPH), no changes were observed in the inducibility of any of these IEGs when comparing between single and repeated administration of AMPH (Fig. 5b,d,e,j,k). Taken together these data show that although NAc neurons in MUT mice are capable of mounting an IEG response to AMPH, both the magnitude and plasticity of this response are significantly altered.

Psychostimulant-induced phosphorylation of MeCP2

Transcriptional regulators that couple psychostimulant exposure to behavioral responses are targets of modulation by psychostimulant-induced intracellular signaling cascades5. Since phosphorylation of MeCP2 at Ser421 (pMeCP2) alters its ability to act as a transcriptional repressor22, we asked whether AMPH induces pMeCP2 within mesolimbocortical neurons. Adult male C57BL/6 mice received an acute injection of Veh or 3mg/kg AMPH, then were euthanized 0.5-24 hrs later and quantitative MeCP2 and pMeCP2 immunoreactivities were assessed in coronal brain sections with antibodies specific to MeCP2 and phospho-Ser421 MeCP222. MeCP2 is expressed in the majority of neurons within the NAc, VTA, and associated limbic structures (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Fig. 4). Veh-treated animals display baseline levels of pMeCP2 immunoreactivities that vary among different brain regions (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. 4). AMPH stimulates a robust, but transient, induction of pMeCP2 in a small population of neurons diffusely distributed throughout the shell and into the core of the NAc, without increasing overall expression of MeCP2 (Fig. 6a–i). AMPH induces pMeCP2 in a dose-dependent fashion, and pMeCP2 is induced also by administration of 10mg/kg cocaine, another psychostimulant (Fig. 6o).

Figure 6. Psychostimulants induce pMeCP2 in the NAc.

a-g, Double immunofluorescence of the NAc with antibodies against pMeCP2 and total MeCP2, 2 h after Veh or 3 mg/kg AMPH. ac - anterior commissure. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. e–g, High magnification enlargement of box shown in c. e, overlay. Scale bar indicates 15 μm; * - co-immunolabeled cells. h, Timecourse of pMeCP2 immunofluorescence within the NAc following 3 mg/kg AMPH (n=8/group). (F6,48=9.04, p<0.0001); * - p=0.018, Veh compared to 0.5 h, and p<0.0001, compared to 2 h. i, Timecourse of total MeCP2 immunofluorescence in the NAc following 3 mg/kg AMPH (n=4-5 mice/time-point). (F6,22=1.28, p=0.31). j–n, Stimulation of dopamine D1-class receptors induces phosphorylation of MeCP2. J–m, pMeCP2 immunofluorescence after Veh (j; Veh), 3 mg/kg AMPH (k; AMPH), 5 mg/kg SKF81297 (l; SKF), or 0.25 mg/kg of SCH22390 15 min prior to AMPH injection (m; SCH+AMPH). Scale bar indicates 45 μm. n, Quantitation of pMeCP2 immunofluorescence intensity (n=6 for Veh- and AMPH-treated groups, n=9 for other groups). (F3,25=16.0, p<0.001). * - p=0.001, Veh compared to AMPH, and p<0.0001, compared to SKF; # - p=0.026, SCH + AMPH compared to AMPH, and p=0.001, compared to SKF. o, Integrated intensity of pMeCP2 immunofluorescence following Veh, 1 or 3 mg/kg AMPH, or 10 mg/kg cocaine. Open circles represent values for individual animals, and the bar represents the group mean (n=5-6/group). (F3,19=12.45, p<0.0001). * - p<0.0001, Veh compared to 3mg/kg AMPH, and p=0.042, compared to 10 mg/kg cocaine. Results displayed as mean ± s.e.m.

AMPH and cocaine increase extracellular DA levels at the synapse, leading to activation of both D1- (D1 and D5) and D2-class (D2, D3, and D4) receptors. To determine whether DA receptor signaling mediates the induction of pMeCP2 by psychostimulants, mice were first injected with Veh or 0.25 mg/kg SCH22390, a D1-class antagonist, followed 15 min later with 3mg/kg AMPH. The antagonist significantly reduced the AMPH-induced expression of pMeCP2 in the NAc, suggesting that activation of D1-class receptors is required for this process (Fig. 6j,k,m,n). When mice were given SKF81297, a D1-class receptor agonist at doses that stimulate locomotor activity in the open field (data not shown), we found that 5mg/kg SKF81297 was sufficient to drive robust phosphorylation of MeCP2 in the NAc (Fig. 6j,l,n). These data suggest that D1-class DA receptor signaling is both sufficient and necessary for AMPH-mediated induction of pMeCP2.

Interestingly, AMPH-induced pMeCP2 is largely restricted to the NAc, as we observe no significant increase of pMeCP2 in the caudate-putamen, VTA, basolateral amygdala, or hippocampus following AMPH treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4). There is an increase in pMeCP2 immunoreactivity in the prelimbic region of the frontal cortex 2 hrs after AMPH administration, however baseline pMeCP2 levels in Veh-treated animals are significantly elevated in prelimbic cortex compared with striatum (Fig. 6a,c; Supplementary Fig. 4).

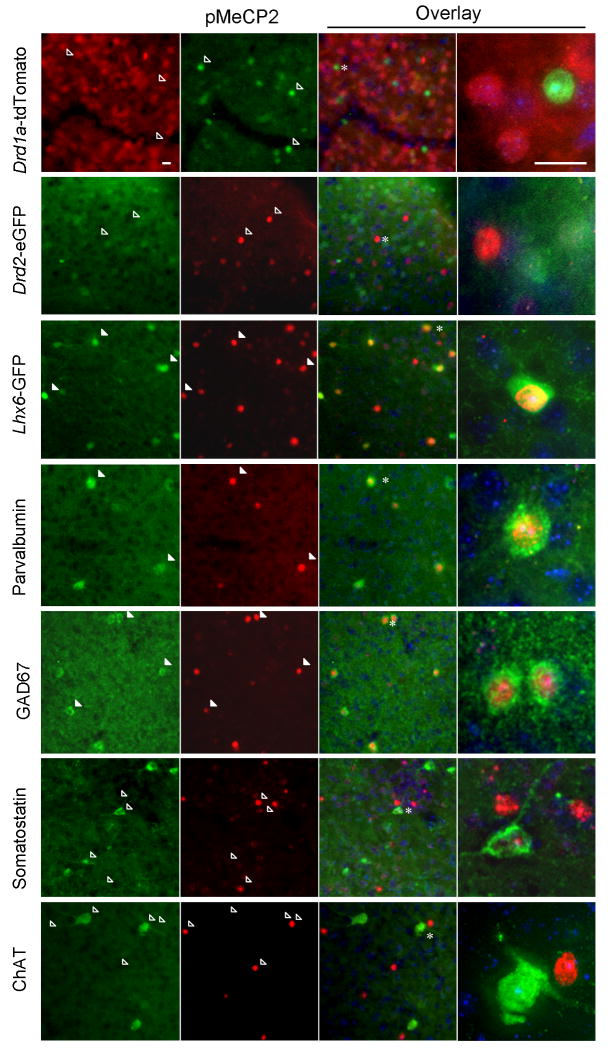

Neurons in the NAc are comprised of two main classes: more than 90% of the cells are MSNs - GABAergic projection neurons that carry efferent signals from the striatum; the remaining neurons are local interneurons that use GABA or acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter29,30. To ascertain which neurons show changes in pMeCP2 levels to AMPH treatment, we first used BAC transgenic mouse lines that express fluorescent proteins in MSNs that express D1 or D2 receptors, respectively31. We were surprised to find no overlap of the D1 or D2 receptor marker proteins with pMeCP2 in either mouse line in the NAc (Fig. 7a,b). Nevertheless, these animals showed a transcriptional response to AMPH in MSNs, because we could detect expression of c-Fos in a subset of fluorescent neurons in both lines of mice (Supplementary Fig. 5). By contrast, following AMPH treatment we observed extensive overlap with pMeCP2 in the Lhx6-GFP BAC transgenic line, which expresses GFP in a subset of GABAergic interneurons in striatum and cortex32 (Fig. 7c; Supplementary Fig. 6). Parvalbumin and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD)-67, two markers of fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons (FSIs)30, show nearly complete colocalization with pMeCP2 in AMPH-treated animals (Fig. 7d,e) suggesting that a large percentage of this population of GABAergic interneurons experience AMPH-induced pMeCP2. No colocalization is seen between pMeCP2 and somatostatin (Fig. 7f), which marks a different class of GABAergic interneurons, or with choline acetyltransferase (Fig. 7g), a marker of cholinergic interneurons. Thus these data demonstrate a striking in vivo selectivity of psychostimulant-mediated induction of pMeCP2, preferentially in FSIs of the NAc.

Figure 7. AMPH selectively induces pMeCP2 in fast spiking GABAergic interneurons in the NAc.

Drd1a-tdTomato (a), Drd2-eGFP (b), Lhx6-GFP (c), or C57BL/6 mice (d–g) were injected with 3 mg/kg AMPH, euthanized 2 h later, brain sections were cut, and immunolabeled for pMeCP2. pMeCP2 staining was compared to tdTomato or eGFP fluorescence in the BAC transgenic mice (a–c), or to immunostaining for parvalbumin (d), glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67)(e), somatostatin (f), or choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (g). Hoechst nuclear dye (blue). Filled arrowheads indicate cells co-immunolabeled with two fluorophores; open arrowheads indicate singly labeled cells; * indicates cells shown at high magnification after 3-D deconvolution. The scale bars indicate 15μM.

pMeCP2 correlates with behavioral sensitization to AMPH

To determine whether regulation of pMeCP2 changes following repeated exposure to psychostimulants, we quantified pMeCP2 in the NAc from mice that had been behaviorally sensitized to AMPH (Fig. 8a,b; Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). All groups that received AMPH on the challenge day (Veh:AMPH; AMPH:AMPH) showed induced pMeCP2 compared to the Veh:Veh and AMPH:Veh groups (Fig. 8c–g), and the extent of induced pMeCP2 was largely confined to the NAc in both groups (data not shown). Mice that were given repeated injections of AMPH but received Veh challenge (AMPH:Veh) showed no enhancement of pMeCP2 above Veh:Veh control (Fig. 8c,d,g), suggesting that pMeCP2 is not persistently elevated by repeated AMPH treatment prior to AMPH challenge.

Figure 8. Increases in pMeCP2 correlate with behavioral sensitization following repeated AMPH administration.

a, Experimental scheme. Arrows represent injections. n=9-10/group. b, Cumulative distance traveled over 1 h following challenge with Veh or AMPH. ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of treatment [F3,35=206.3, p<0.001]. * - ps<0.0001, Veh:Veh or AMPH:Veh compared to Veh:AMPH or AMPH:AMPH groups; # - p=0.025, Veh:AMPH compared to AMPH:AMPH. c-f, pMeCP2 immunofluorescence in the NAc 2 h after challenge injections of Veh (c,d) or AMPH (e,f) from mice that received repeated injections of Veh (c,e) or AMPH (d,f). Scale bar indicates 30 μm. g, Quantitation of pMeCP2 immunofluorescence intensity in the NAc. ANOVA indicated a significant effect of treatment (F3,27=8.3, p<0.001). * - p=0.011, Veh:Veh compared to Veh:AMPH, and p=0.017, Veh:Veh compared to AMPH:AMPH; # - p=0.007, AMPH:Veh compared to Veh:AMPH, and p=0.013, compared to AMPH:AMPH. h–k, Pearson product correlations of pMeCP2 immunofluorescence intensity in the NAc and cumulative locomotor activity from individual animals. h,i, pMeCP2 expression does not correlate with locomotor activity in mice that received Veh injection (Veh:Veh and AMPH:Veh) at challenge, r=0.17, p=0.26 (Veh:Veh) and r=0,55, p=0.096 (AMPH:Veh), n=9 and 10. j, pMeCP2 expression does not correlate with locomotor activity in mice that received a single AMPH injection (Veh:AMPH) at challenge, r= -0.073, p= 0.80, n=15. k, pMeCP2 expression strongly correlates with locomotor activity in animals that received repeated AMPH injections and AMPH at challenge (AMPH:AMPH), r=0.61, p=0.0087, n=17. Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

However, a striking difference between the single AMPH (Veh:AMPH) and repeated AMPH (AMPH:AMPH) treatment groups emerged when a correlational analysis was applied to locomotor activity and NAc pMeCP2 expression in individual animals. No significant relationship between behavior and pMeCP2 induction was observed in individual animals that received a single injection of AMPH (Veh:AMPH) (Fig. 8j; Supplementary Fig. 7c,d) or in either the Veh:Veh or AMPH:Veh groups (Fig. 8h,i). By contrast, we observed a strong correlation of pMeCP2 expression with locomotion in the AMPH-treated animals given AMPH at challenge (AMPH:AMPH) (Fig. 8k; Supplementary Fig. 7e,f). We found a similar correlation in the same animals between pMeCP2 and the expression of behavioral stereotypical activities (Supplementary Fig. 8). These data indicate that for individual animals within the AMPH:AMPH group, the magnitude of pMeCP2 expression in the NAc predicts the degree of behavioral sensitization.

Discussion

Using two different approaches we found that changes in Mecp2 alter both AMPH-induced locomotion and the rewarding properties of this psychostimulant in CPP. First using lentivirus to knockdown or overexpress MeCP2 locally within the NAc, we found that levels of MeCP2 are inversely correlated with AMPH-induced locomotion and CPP. Interestingly, repeated cocaine administration is reported to drive an increase in MeCP2 expression in a subset of neurons in the dorsal caudate-putamen, frontal cortex, and dentate gyrus33. Together with our experimental data, these observations raise the possibility that local alterations in MeCP2 expression within the mesolimbocortical DA circuit may act as a homeostatic compensatory mechanism to limit behavioral responses to AMPH. In our second approach, we found that hypomorphic Mecp2308/y MUT mice have altered behavioral responses to both acute and repeated AMPH administration, further supporting a role for this transcriptional regulator in modulating behavioral responses to psychostimulants. Similar to effects of lentiviral-mediated knockdown, the Mecp2308/y MUT mice displayed enhanced locomotor responses to acute AMPH administration. However unlike the virally-infected mice, the Mecp2308/y mutants failed to show further enhanced locomotor activities to repeated AMPH injection, and they displayed impaired CPP rather than the enhanced CPP we observed with lentiviral-mediated knockdown of Mecp2.

One explanation for differences we observe between requirements for MeCP2 in the adult NAc and the behavioral phenotypes in the Mecp2308 mice is that some of the behavioral effects of the constitutive mutation may arise secondary to changes in mesolimbocortical circuit development. In this regard, we have shown that Mecp2308/y MUT mice have a 2-fold increase in the number of NAc GABAergic synapses. Null mutations in Mecp2 are associated with altered GABAergic synapse numbers in thalamic nuclei, although the mechanisms by which MeCP2 regulates GABAergic synapse development remain unknown34. Most inhibitory striatal synapses are of local origin: ∼70% are from MSN collaterals, whereas the remainder arises from GABAergic interneurons35. MeCP2 is expressed in both types of neurons, and the magnitude of the increase in GABAergic synapses we detected is most consistent with the possibility that synapses in both populations of neurons are altered in Mecp2308/y MUT mice. Although the specific behavioral consequences of changing GABAergic synapse connectivity within the NAc are unknown, chronic cocaine administration can increase the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory currents in DA D1-receptor expressing neurons in striatal slices36.

However beyond this evidence for altered NAc circuit development, we also find deficient neuronal plasticity in the NAc of adult Mecp2308/y MUT mice following repeated AMPH administration. Changes in MSN dendritic spine density represent one cellular mechanism that may contribute to the development and/or expression of behavioral sensitization and CPP. Previous studies have demonstrated that repeated psychostimulant treatment induces an increase in the spine densities of MSNs in the NAc that persists for up to 1 month following drug withdrawal2, although whether this structural synaptic plasticity promotes7,10 or limits9,37 behavioral responses to psychostimulants remains unclear. We observe that spine densities are not increased by chronic AMPH treatment in Mecp2308/y MUT mice. Furthermore we find that these mice have deficient regulation of striatal IEG expression following repeated AMPH treatment. Acute treatment with cocaine or AMPH induces Fos, Fosb, Fosl2, and Junb transcription in the striatum42, while repeated psychostimulant exposure changes the inducibility of these IEGs over time through a process that is proposed to involve epigenetic mechanisms of chromatin regulation6,28,43. In the NAc of Mecp2308/y MUT mice, acute AMPH-induced expression of FosB is impaired while that of JunB is enhanced. Furthermore these mice fail to show plasticity of IEG inducibility following repeated AMPH. The Fos and Jun family of transcription factors are functionally important transcriptional targets of psychostimulants38-41. In particular the Fosb splice variant ΔFosB lies near the pinnacle of a transcriptional cascade that increases dendritic spine densities in the NAc and sensitizes behavioral responses to psychostimulants10. Altered Fosb transcription in the Mecp308/y mice could contribute to changes in spine densities and AMPH-induced behavior. However it is important to note that the drug injection schedules utilized in the CPP, spine density, and gene expression paradigms employed here are not identical, so whether these biochemical and cellular deficiencies in the Mecp2308/y mice are occurring concurrent with the behavioral changes remains to be determined. Furthermore although we observe no differences in spine densities between genotypes at baseline, the Mecp2308/y MUT mice are much more sensitive to the locomotor-stimulating effects of psychostimulants than the Mecp2+/y WT controls. Together, these data emphasize the challenges of linking single neural adaptation (e.g., dendritic spine density) with the behavioral output of the mesolimbocortical DA circuit, and they raise the possibility that multiple cellular mechanisms may be capable of generating similar behavioral states.

We find that psychostimulants drive DA-dependent Ser421 phosphorylation of MeCP2 in brain, suggesting a mechanism through which these drugs may regulate MeCP2 function in close temporal association with the reception of rewarding stimuli. Pharmacological activation of D1-class DA receptors in vivo is required for the psychostimulant-dependent induction of pMeCP2 in a subset of GABAergic interneurons within the NAc. By contrast, these same stimuli fail to induce pMeCP2 in striatal MSNs despite their containing high levels of DA receptors. Since DA exerts systems-level effects on network excitability29 and because MeCP2 phosphorylation is regulated by the activation of glutamate receptor-coupled intracellular calcium signaling cascades22, the most parsimonious interpretation of our data is that the selective pattern of MeCP2 phosphorylation following DA receptor activation in vivo is secondary to changes in neuronal firing.

Very little is known about the effects of chronic psychostimulant exposure on the firing properties or plasticity of striatal FSIs. Nonetheless it has been shown that DA excites FSIs in striatal slice preparations through pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms44. A recent study has shown that acute administration of AMPH increases the firing rate of FSIs in the striatum of freely-moving rats in vivo45. Despite their small numbers, each FSI makes numerous inhibitory synapses onto the soma and proximal dendrites of multiple MSNs such that cortical activation of a single FSI is sufficient to delay or block the generation of action potentials in a large number of MSNs46,47. Phosphorylated MeCP2 may act in FSIs to acutely modulate their function or, alternatively, changes in the extent of pMeCP2 following repeated AMPH exposure may reflect plasticity of the synaptic connections and intracellular signaling pathways that drive this phosphorylation event. In either case, our data suggest that future studies addressing DA-dependent plasticity and the role of pMeCP2 in FSIs of the NAc may lead to novel insights into our understanding of behavioral responses to drugs of abuse.

Methods

Mouse Strains

We purchased adult (8-10 week old) male C57BL/6 mice from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Drd1a-tdTomato34 and Drd2-GFP (GENSAT: www.gensat.org) BAC transgenic mice were provided by Dr. Nicole Calakos (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC). Dr. Franck Polleux (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) provided Lhx6-GFP BAC transgenic mice (GENSAT: www.gensat.org). We purchased Mecp2308 mice congenic on a C57BL/6J background from Jackson Laboratories (B6.129S-Mecp2tm1Hzo/J, stock number 005439).

Antibodies

We used following antibodies in this study: mouse anti-MeCP2 1:1000 (ab5005-100; AbCAM, Cambridge, MA), rabbit anti-MeCP2 1:1000 (gift from M.E. Greenberg, Children's Hospital, Boston, MA), rabbit anti-phospho-Ser421 MeCP2 (gift from M.E. Greenberg, Children's Hospital, Boston, MA and raised as described below), mouse anti-parvalbumin 1:1000 (P3088; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), mouse anti-GAD67 1:1,000 (MAB5406; Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica, MA), mouse anti-GAD65 1:1000 (MAB351; Chemicon/Millipore), rabbit anti-VGAT 1:1000 (AB5062P; Chemicon/Millipore), guinea pig anti-VGLUT1 1:250 (AB5905; Chemicon/Millipore), goat anti-choline acetyltransferase 1:1000 (AB144P; Chemicon/Millipore), rabbit anti-DARPP32 1:1000 (AB1656; Chemicon/Millipore), rat anti-somatostatin 1:200 (MAB354; Chemicon/Millipore), rabbit anti-c-Fos 1:15,000 (PC38; Calbiochem), rabbit anti-FosB 1:100 (sc-48, Santa Cruz), mouse anti-JunB 1:100 (sc-8051; Santa Cruz); secondary antibodies conjugated to Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5 1:500 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA and Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Phospho-Ser421 MeCP2 Antibody Generation

We generated a polyclonal phosphor-Ser421-MeCP2 antibody as previously described22. In brief, New Zealand white rabbits (Covance Research Products, Denver, PA) were injected with the MeCP2 Ser421 phosphopeptide CEKMPRGGpSLESD (Tufts Synthesis Facility, Boston, MA). Antiserum pooled from production bleeding was first applied through a subtraction column conjugated with unphosphorylated MeCP2 Ser421 peptide (SulfoLink Gel; Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL). The unbound flow-through was then incubated with an affinity column conjugated to the phosphorylated 421 MeCP2 peptide. We eluted the affinity-purified phospho-Ser421 MeCP2 antibody and microdialysed overnight to remove salt. We tested the antibody for phospho-specificity by dot blot with phospho- and non-phospho-Ser421 peptides (data not shown).

Drugs

All injections were given i.p. We injected mice in their home cages except on days when behavior was analyzed. We habituated the mice to the open field for 1 hr to establish baseline locomotor activity, administered vehicle or drug, and immediately returned mice to the open field. We used the following drugs: AMPH (Sigma), cocaine (Sigma), SKF81297 (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO), SCH23390 (Tocris), and quinpirole (Tocris). All drugs were dissolved in H2O as vehicle except SKF81297 which was dissolved in 5% DMSO and diluted to 0.5%. We performed all procedures under an approved protocol from the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Stereotactic Surgery

Lentiviruses expressing an shRNA targeting MeCP222, a control shRNA containing a scrambled shRNA sequence (5′-AAACAAGCCCATTCGCGGATT-3′), and overexpression lentiviruses expressing either GFP48 or MeCP2-IRES-GFP were cloned under control of the ubiquitin promoter in the vector pFUIGW22 and packaged following standard procedures22. We performed stereotactic surgery following previously established procedures9. Mice were deeply anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400mg/kg) for stereotactic surgery. With the T-vertical bar set at 10° angle, and using coordinates of AP+1.8 ML+1.5 DV-4.4, we infused 0.5μl of virus into the NAc bilaterally at a rate of 0.1μl/min. 7-9 days later we conducted behavioral experiments then sectioned brains to confirm trajectory of the needle track and the extent of viral infection as determined by expression of GFP.

Behavioral Sensitization

Mice were injected with vehicle or 3mg/kg AMPH once a day for 5 consecutive days, either in their home cage or the open field as indicated in the text, withdrawn from drug for 7 days, and challenged with vehicle or 3mg/kg AMPH while activity was measured in the open field (Accuscan Instruments, Columbus, OH). We monitored horizontal (distance traveled in cm) or stereotypical activity (repeated beam-breaks <1 sec) under 340 lux illumination.

Conditioned Place Preference

We conducted CPP testing in a three-chambered apparatus equipped with infrared diodes (Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT). Two equal sized chambers (16.8 × 12.7 × 12.7 cm) differ in color and floor texture and are joined by a smaller start box (7.2 × 12.7 ×12.7 cm) with manually operated doors. We conducted testing over 11 or 17 days, as specified. On the first three days, we acclimatized MUT and WT littermates to the CPP apparatus by placing them into the center chamber, and allowing them free access to the entire apparatus for 30mins. After day 3, we evaluated preferences for the two test chambers and designated the least-preferred chamber as the conditioning chamber where the animal would receive AMPH. Note, this is a commonly used experimental design that controls for pre-existing chamber bias; however this paradigm does not unequivocally distinguish the contribution of eliminating an avoidance response to the drug-paired chamber from the overall development of preference for the drug-paired chamber. Conditioning began on day 4 and consisted of 3 or 6 two-day pairing cycles. On the first day (day 4) of conditioning and on every other day (4, 6, 8 for 3 pairing, continuing onto 10, 12, and 14 for 6 pairing) we administered AMPH (1 or 3mg/kg, i.p.) and confined the mice to one chamber for 30 min. On alternate days (5, 7, 9 for 3 pairing, or continuing onto 11, 13 and 15 for 6 pairing), we administered Veh and confined the mice to the opposite chamber. Forty-eight hours following conditioning (test day 11 for 3 pairing, or day 17 for 6 pairing), we returned mice to the center chamber and allowed free access to the entire apparatus for 30mins. For data analyses, we compared times in the Veh and AMPH chambers or we calculated preferences scores as the amount of time the animal spent in the AMPH relative to the Veh chamber.

Sucrose Preference

We assessed sucrose preference using a two bottle choice test. We housed Mice individually for 7 days prior to and throughout the study, and performed testing in the home cage. We removed water bottles 0.5 hrs before the beginning of the dark cycle, and fluid deprived the mice for 1 hour to enhance drinking. During the 2 hrs test period, we permitted mice to drink freely from two bottles. We paired water day with either 0.25% sucrose, 0.5% sucrose, 1% sucrose, or, 2% sucrose in that order, with each pairing separated by a day in which we presented water in both bottles. Following the series of sucrose solutions we repeated the choice test by pairing water with 0.0075mM, 0.015mM, or 0.03mM quinine. We determined preference for the sucrose or quinine solutions by dividing the volume of sucrose or quinine solution consumed by the total liquid consumption during testing on each day.

Golgi-Cox Staining for Spine Density

We injected Mecp2308/YMUT and WT mice daily in their home cages with either 3mg/kg AMPH or Veh for 21 days. Twenty-four hours after the final drug treatment, we anesthetized mice with Nembutal and sacrificed them by transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Golgi-Cox staining procedures were performed following the manufacturer's instructions (FD NeuroTechnologies, Ellicott City, MD) with minor modifications. We postfixed brains for 2 weeks with Solution A and B of the FD Rapid GolgiStain™ Kit, and then treated with Solution C for 7 days. We cut coronal sections (100 mm thick) by Cryostat and transferred sections to Solution C. After brief rinsing with distilled water, we stained floating sections with Solution D and E for 30 min and then transferred to gelatin solution. We mounted sections on glass slides, dehydrated them through a graded series of ethanol concentrations, then mounted them with Permount. For quantification, we collected z-stack images of neurons in the NAc using a Retiga-4000DC camera on a Leica DMI4000 microscope under 63× oil. Using the Average module in the Stack Arithmetic Process of Metamorph 7.0, stack representations of each dendrite were compressed into a single image. We used a previously described protocol to quantitate spine density9. We identified labeled MSNs in the shell of the NAc for which we could detect secondary and tertiary dendrites (30-100μm from the soma). An investigator blind to genotype and treatment randomly selected 6-8 such dendritic segments of 30-70μm in length for each brain and manually counted spine number.

Immunofluorescent Staining of Brain Sections

At the indicated times (or 2 hrs after drug administration if not specified), we transcardially perfused mice with PBS then 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M PBS, postfixed brains in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS overnight, then sunk them in 30% sucrose/PBS overnight. We cut forty μm coronal sections on a freezing microtome and identified brain regions by anatomical landmarks. To minimize variation in immunostaining across treatment groups, we first spread sections from different individual mice into a Petri dish filled with PBS and photographed them with a high-resolution digital camera (Sony DSC-H1). We then mixed all sections for immunolabeling within a single chamber. We used the images collected before the staining to recover the identity of each section after staining. For immunolabeling, tissue sections were first permeabilized with either 1% (the pMeCP2 antibody) or 0.3% (all other experiments) Triton X-100 for 1 hr at room temperature, then blocked with 16% goat serum in PBS. We incubated sections with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Whenever possible, we performed double immunostaining with primary antibodies raised in two species for co-localization on single sections. We applied species-specific fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature, and nuclei were labeled with Hoechst dye (Sigma) to facilitate anatomical localization of structures.

Image Analyses

For quantitative immunofluorescence, we captured images on a Leica DMI4000 inverted fluorescence microscope using a Cascade 512B camera. We quantified digital images using MetaMorph 7 Image Analysis software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All images within one experiment were taken with a constant exposure time and aperture, and quantified using a single threshold value. We determined the threshold value as the average background immunofluorescence of vehicle control sections in each experiment. To reduce variation between animals, we counted pMeCP2 and total MeCP2 cell numbers and integrated intensity from a constant-sized region across the shell of the NAc. We used the Count Nuclei module in MetaMorph 7.0 to evaluate both cell numbers and integrated intensities of the pMeCP2 or MeCP2 immunoreactivities. Quantitation of representative images from key experiments was independently verified by an investigator blind to the treatment conditions. For high resolution co-localization, we captured images in a z-stack in MetaMorph 7.0 and subjected them to 3-D deconvolution processing using AutoQuant X2.1.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Bethesda, MD). For synaptic protein quantitation, we captured three separate images from each section in z-stacks with a 63× oil lens. After 3D-deconvolution processing, a four consecutive image stack (equivalent to 2μm thickness) was merged using the Average Stack Arithmetic module in MetaMorph 7.0. We then quantitated the merged images using the Count Nuclei module in MetaMorph as described above. We eliminated the image farthest from the mean and the remainder were averaged to obtain a value for each animal.

Statistical Analyses

We performed all statistical analyses using SPSS v11.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The data are depicted as means and standard errors of the mean. We analyzed comparisons of protein expression (e.g. pMeCP2 or total MeCP2) or spine density data with one-way or two-way univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) as necessary. We analyzed locomotor activity in the open field using multivariate repeated measures of ANOVA (RMANOVA) for activities at baseline and at 1 to 2-hrs post-injection over 5 min intervals, using time as the within-subjects effect, and genotype and treatment as the between-subjects effects. In some experiments, we aggregated these data over the 1 to 2-hrs following injection as noted and differences between treatments were analyzed with an independent measures t-test. We analyzed CPP and sucrose preference test data within each genotype or treatment using RMANOVA, with preference scores as the within-subjects effect and treatment (e.g. AMPH dose, sucrose and quinine concentration) as the between-subjects effect. In all cases, we conducted post-hoc analyses using Bonferroni corrected pair-wise comparisons. We assessed the correlation between pMeCP2 immunoreactivity and locomotor activity with Pearson correlation coefficients. In all cases, we considered p<0.05 statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to M.E. Greenberg, Z. Zhou, and S. Cohen for sharing unpublished data and reagents. We thank N. Calakos and F. Polleux for providing transgenic mice; K. Vaishnav, J. Zhou, L. Du, M. Fukui, M. Cools, N. Negbenebor, P. Pattabiraman, W.-H. Qian, R. Chereau, and M. Presby for technical assistance; and D. Fitzpatrick, G. Feng, J.O. McNamara, A. Brunet and M. Caron for critical reading of the manuscript. Support for this work was provided by National Institute of Drug Abuse grants R01-DA022202 (A.E.W.) and F32-DA025447 (J.V.D.); Grant #1-FY07-482 from the March of Dimes Foundation (A.E.W.); along with the Duke University postdoctoral training program in Fundamental and Translational Neuroscience, and the predoctoral Pharmacological Sciences Training Program.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: J.V.D. conducted the behavioral and biochemical experiments, performed the stereotactic surgery, ran statistical analyses, and wrote the paper. R.M.R. assisted with design and execution of the behavioral experiments and oversaw the statistical analyses. A.N.H. assisted with the behavioral and biochemical experiments and performed the sucrose preference test. I.-H. K. did the Golgi staining. W.C.W. helped to design the study, supervised all of the behavioral experiments, and wrote the paper. A.E.W. designed the study, supervised the project, and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural Mechanisms of Addiction: The Role of Reward-Related Learning and Memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson TE, Kolb B. Persistent structural modifications in nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex neurons produced by previous experience with amphetamine. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8491–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08491.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YH, et al. In vivo cocaine experience generates silent synapses. Neuron. 2009;63:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas MJ, Beurrier C, Bonci A, Malenka RC. Long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens: a neural correlate of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1217–23. doi: 10.1038/nn757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moratalla R, Elibol B, Vallejo M, Graybiel AM. Network-level changes in expression of inducible Fos-Jun proteins in the striatum during chronic cocaine treatment and withdrawal. Neuron. 1996;17:147–56. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo SJ, et al. Nuclear factor kappa B signaling regulates neuronal morphology and cocaine reward. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3529–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6173-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlezon WA, Jr, et al. Regulation of cocaine reward by CREB. Science. 1998;282:2272–5. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulipparacharuvil S, et al. Cocaine regulates MEF2 to control synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:621–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maze I, et al. Essential role of the histone methyltransferase G9a in cocaine-induced plasticity. Science. 2010;327:213–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1179438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao HT, Zoghbi HY, Rosenmund C. MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron. 2007;56:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dani VS, et al. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12560–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tropea D, et al. Partial reversal of Rett Syndrome-like symptoms in MeCP2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2029–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812394106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson ED, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. MeCP2-dependent transcriptional repression regulates excitatory neurotransmission. Current Biology. 2006;16:710–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giacometti E, Luikenhuis S, Beard C, Jaenisch R. Partial rescue of MeCP2 deficiency by postnatal activation of MeCP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610593104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahbazian MD, et al. Mice with truncated MeCP2 recapitulate many Rett Syndrome features and display hyperacetylation of histone H3. Neuron. 2002;35:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samaco RC, et al. A partial loss of function allele of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 predicts a human neurodevelopmental syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1718–27. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moretti P, et al. Learning and memory and synaptic plasticity are impaired in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J Neurosci. 2006;26:319–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2623-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGill BE, et al. Enhanced anxiety and stress-induced corticosterone release are associated with increased Crh expression in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18267–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608702103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moretti P, Bouwknecht JA, Teague R, Paylor R, Zoghbi HY. Abnormalities of social interactions and home-cage behavior in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:205–20. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Z, et al. Brain-specific phosphorylation of MeCP2 regulates activity-dependent Bdnf transcription, dendritic growth, and spine maturation. Neuron. 2006;52:255–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen WG, et al. Upstream stimulatory factors are mediators of calcium-responsive transcription in neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:2572–2581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02572.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poo Mm. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:1–9. doi: 10.1038/35049004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stearns NA, et al. Behavioral and anatomical abnormalities in Mecp2 mutant mice: a model for Rett syndrome. Neuroscience. 2007;146:907–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ. Glutamatergic mechanisms in addiction. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:373–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kauer JA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:844–58. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renthal W, et al. Delta FosB mediates epigenetic desensitization of the c-fos gene after chronic amphetamine exposure. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7344–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1043-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicola SM, Surmeier J, Malenka RC. Dopaminergic modulation of neuronal excitability in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:185–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Augood SJ, Emson PC. Striatal interneurones: chemical, physiological and morphological characterization. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:527–35. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)98374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shuen JA, Chen M, Gloss B, Calakos N. Drd1a-tdTomato BAC transgenic mice for simultaneous visualization of medium spiny neurons in the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2681–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5492-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cobos I, Long JE, Thwin MT, Rubenstein JL. Cellular patterns of transcription factor expression in developing cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(1):i82–8. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassel S, et al. Fluoxetine and cocaine induce the epigenetic factors MeCP2 and MBD1 in adult rat brain. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;70:487–92. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang ZW, Zak JD, Liu H. MeCP2 is required for normal development of GABAergic circuits in the thalamus. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2010;103:2470–81. doi: 10.1152/jn.00601.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guzman JN, et al. Dopaminergic modulation of axon collaterals interconnecting spiny neurons of the rat striatum. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8931–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08931.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heiman M, et al. A translational profiling approach for the molecular characterization of CNS cell types. Cell. 2008;135:738–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norrholm SD, et al. Cocaine-induced proliferation of dendritic spines in nucleus accumbens is dependent on the activity of cyclin-dependent kinase-5. Neuroscience. 2003;116:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00560-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, et al. c-Fos facilitates the acquisition and extinction of cocaine-induced persistent changes. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13287–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3795-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiroi N, et al. FosB mutant mice: loss of chronic cocaine induction of Fos-related proteins and heightened sensitivity to cocaine's psychomotor and rewarding effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:10397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelz MB, et al. Expression of the transcription factor deltaFosB in the brain controls sensitivity to cocaine. Nature. 1999;401:272–6. doi: 10.1038/45790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bibb JA, et al. Effects of chronic exposure to cocaine are regulated by the neuronal protein Cdk5. Nature. 2001;410:376–80. doi: 10.1038/35066591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang D, et al. The dopamine D1 receptor is a critical mediator for cocaine-induced gene expression. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1453–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hope B, Kosofsky B, Hyman SE, Nestler EJ. Regulation of immediate early gene expression and AP-1 binding in the rat nucleus accumbens by chronic cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5764–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bracci E, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Dopamine excites fast-spiking interneurons in the striatum. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2190–4. doi: 10.1152/jn.00754.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiltschko AB, Pettibone JR, Berke JD. Opposite effects of stimulant and antipsychotic drugs on striatal fast-spiking interneurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1261–70. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koos T, Tepper JM. Inhibitory control of neostriatal projection neurons by GABAergic interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:467–72. doi: 10.1038/8138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gruber AJ, Powell EM, O'Donnell P. Cortically activated interneurons shape spatial aspects of cortico-accumbens processing. J Neurophysiol. 2009 doi: 10.1152/jn.91002.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lois C, Hong EJ, Pease S, Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science. 2002;295:868–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1067081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.