Abstract

Sequence-directed genetic interference pathways control gene expression and preserve genome integrity in all kingdoms of life. The importance of such pathways is highlighted by the extensive study of RNA interference (RNAi) and related processes in eukaryotes. In many bacteria and most archaea, clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) are involved in a more recently discovered interference pathway that protects cells from bacteriophages and conjugative plasmids. CRISPR sequences provide an adaptive, heritable record of past infections and express CRISPR RNAs — small RNAs that target invasive nucleic acids. Here, we review the mechanisms of CRISPR interference and its roles in microbial physiology and evolution. We also discuss potential applications of this novel interference pathway.

The acquisition of new genes that confer a selective advantage is an important factor in genome evolution. Considerable proportions of bacterial and archaeal genomes consist of genes derived from the exchange of genetic material among related or unrelated species1, which is known as horizontal gene transfer (HGT). HGT occurs by uptake of environmental DNA (transformation) or by the incorporation of heterologous DNA carried on mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids (conjugation) and bacteriophages (transduction)2.

However, only a miniscule fraction of acquired genes confers an immediate selective advantage. Therefore bacteria and archaea have developed many mechanisms to prevent HGT, such as DNA restriction and surface exclusion2. Recently, arrays of clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) have been identified as determinants of a novel genetic interference pathway that limits at least two major routes of HGT — conjugation and transduction. Like eukaryotic RNA interference (RNAi) and related pathways (with which CRISPR interference is analogous but not homologous), CRISPR interference provides the host with an efficient antiviral defence mechanism.

In contrast to other gene transfer and phage defence mechanisms, CRISPR interference is an adaptive immune system that can be reprogrammed to reject invading DNA molecules that have not been previously encountered. CRISPRs are separated by short spacer sequences that match bacteriophage or plasmid sequences and specify the targets of interference. Upon phage infection, CRISPR arrays can acquire new repeat-spacer units that match the challenging phage. Cells with this extended CRISPR locus will survive phage infection and thrive. Therefore the spacer content of CRISPR arrays reflects the many different phages and plasmids that have been encountered by the host, and these spacers can be expanded rapidly in response to new invasions. Accordingly, CRISPRs constitute a ‘genetic memory’ that ensures the rejection of new, returning and ever-present invading DNA molecules.

In this Review we provide a perspective on how CRISPR elements were discovered, their classification and their distribution among bacterial and archaeal genomes. We describe the advances that have been made towards understanding the mechanisms of CRISPR function and the important roles that these arrays have in the evolution of bacteria, archaea and their phages. We conclude by discussing current and potential applications of this novel genetic interference pathway.

Discovery of the CRISPR system

In 1987, Ishino et al.3 cloned and sequenced the iap gene, which is responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli. Immediately downstream of iap, the authors noted a set of 29-nucleotide (nt) repeats separated by unrelated, non-repetitive and similarly short sequences (spacers), which they cloned and sequenced in a subsequent study4. This constituted the first report of a CRISPR locus and was followed by similar descriptions of repeats derived from gene5–8 or whole-genome9–14 sequencing projects in bacteria and archaea. The accumulation of available genomic sequences led Mojica et al.15 to recognize CRISPRs as a family of repeats that are present in many such species.

In 2002, Jansen et al.16 coined the term CRISPR to reflect the particular structure of these loci (FIG. 1). Typically, a repeat cluster is preceded by a ‘leader’ sequence, an AT-rich region several hundred base pairs long with intraspecies but not interspecies conservation16. CRISPR-associated (cas) genes, a set of conserved protein-coding genes that are associated with these loci, are usually present on one side of the array. Analysis of spacer sequences in several CRISPR loci revealed that spacers match sequences from foreign, mobile genetic elements, such as bacteriophages and plasmids17–19. Early studies17 also noted a correlation between phage sensitivity and the absence of spacers matching the sequence of that particular phage, which suggests an immune function for CRISPR loci. The comparison of CRISPR loci from a collection of Yersinia pestis strains revealed that acquisition of new spacers occurs in a polarized fashion, with new units being added at one end of the cluster19. These results suggested the existence of a mechanism that exploits the base-pairing potential of nucleic acids to enable sequence-based interference of phage infection, gene expression, or both. This possibility, which was supported by a detailed bioinformatic analysis of the cas genes that revealed a bias towards proteins that are predicted to facilitate transactions among nucleic acids, led to the proposition that CRISPR immunity could function in a manner analogous to eukaryotic RNAi20,21, which also uses nucleic acid sequences to guide a gene-silencing pathway.

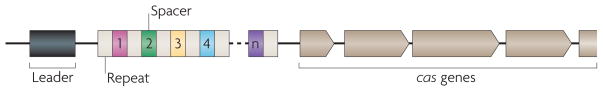

Figure 1. Features of CRISPR loci.

Typically, clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs, white boxes) are preceded by a leader sequence (black box) that is AT-rich but otherwise not conserved. The number of repeats can vary substantially, from a minimum of two to a few hundred. Repeat length, however, is restricted to 23 to 50 nucleotides. Repeats are separated by similarly sized, non-repetitive spacers (coloured boxes) that share sequence identity with fragments of plasmids and bacteriophage genomes and specify the targets of CRISPR interference. A set of CRISPR-associated (cas) genes immediately precedes or follows the repeats. These genes are conserved, can be classified into different families and subtypes, and encode the protein machinery responsible for CRISPR activity.

In 2007, a seminal study by Barrangou et al.22 showed that CRISPR loci specify an adaptive immune pathway that protects Streptococcus thermophilus against phage infection. This study provided the first experimental evidence that sequence identity between the spacer and its match in the phage genome (the protospacer) is required for CRISPR immunity, that new repeat-spacer units are acquired upon phage challenge and that cas genes are necessary for CRISPR function. More recently, we showed that CRISPR interference can limit plasmid conjugation in Staphylococcus epidermidis23, demonstrating a broader role for CRISPRs in the prevention of HGT in bacteria.

Distribution and classification of CRISPR loci

Approximately 40% of sequenced bacterial genomes, and ~90% of those from archaea, contain at least one CRISPR locus24. It is puzzling why more than half of all sequenced bacterial genomes lack CRISPR loci when they are so widespread in archaea; one possible explanation for this apparent inequality may be a genome sequencing bias towards long-established laboratory strains of bacteria, which may have lost CRISPR loci owing to a lack of exposure to bacteriophages for many generations. Regarding the number of loci per genome, the archaean Methanocaldococcus jannaschii9 is the current record holder with 18 clusters. The number of repeat-spacer units per array ranges from just a few to several hundred, but the average is 66. The genome of the thermophilic bacterium Chloroflexus sp. Y-400-fl contains the highest number of repeat-spacer units observed so far, with 374 units in 1 of its 4 CRISPR loci. The repeat sequences vary, even among CRISPR loci in the same genome, and some exhibit limited dyad symmetry. Based on sequence similarity and the potential to form stem–loop structures, CRISPRs can be classified into 12 categories25. Analysis of the current CRISPR database24 reveals that repeats range from 23- to 50-nt long and have an average length of 31 nt, whereas spacer sequences range from 17- to 84-nt long and have an average length of 36 nt. Only ~2% of the total spacer sequences have matches in Genbank18,21, which is probably due to the minuscule proportion of extant bacteriophages and plasmids that have been sequenced, and this percentage increases significantly when community genomic data from bacteria and phages present in a particular microbial niche are analysed26,27.

The complexity of CRISPR loci is multiplied by the presence of different sets of cas genes in the vicinity of the repeats. With only one exception (the bacterium Thermoplasma acidophilum), all CRISPR arrays abut a set of cas genes <1 kb away28 that are absent from genomes devoid of CRISPR loci. More than 40 cas gene families have been identified21,28, and there is an exceptional variability in the cas genes that accompany each repeat cluster. Two groups have made considerable efforts to classify CRISPR systems into different subtypes that share flanking cas genes21,28. Haft et al.28 established 45 gene families associated with CRISPR loci that can be classified into eight CRISPR subtypes that often share gene order as well as content (TABLE 1). Interestingly, there is also a correlation between the characteristics of the repeats and the cas subtype associated with them28,29. Six cas gene families (cas1–cas6) are found in a wide range of CRISPR subtypes and are considered ‘core’ cas genes (TABLE 2). Of these, only cas1 and cas2 are present in all CRISPR loci (although in some cases Cas2 is encoded as a fused domain of a Cas3 protein).

Table 1.

Classification of Cas protein subtypes

| subtype name* | Reference organism | core genes | subtype-specific genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecoli | Escherichia coli | cas1–cas3 | cse1–cse4 and cas5e‡ |

| Ypest | Yersinia pestis | cas1–cas3 | csy1–csy4 |

| Nmeni | Neisseria meningitidis | cas1-cas2 | csn1–csn2 |

| Dvulg | Desulfovibrio vulgaris | cas1-cas4 | csd1–csd2 and cas5d‡ |

| Tneap | Thermotoga neapolitana | cas1–cas4 and cas6 | cst1–cst2 and cas5t‡ |

| Hmari | Haloarcula marismortui | cas1–cas4 and cas6 | csh1–csh2 and cas5h‡ |

| Apern | Aeropyrum pernix | cas1–cas6 | csa1–csa5 |

| Mtube | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | cas1–cas2 and cas6 | csm1–csm5 |

| RAMP module§ | - | None | cmr1–cmr6 |

As described in Haft et al.28 and adopted by the Integrated Microbial Genomes data management system (http://img.jgi.doe.gov). Each CRISPR subtype is named after a reference genome in which there is only one CRISPR locus.

Many members of the Cas5 family contain a conserved amino-terminal domain, but the rest of the sequence seems to be subtype-specific with no conservation across other subtypes. Therefore, cas5 gene names are followed by a letter denoting the subtype to which they belong.

The RAMP superfamily was found to be linked to CRISPR loci by Makarova et al.31. The Cas module RAMP — which contains six genes, cmr1–cmr6 — is present in a range of bacteria and archaea and does not seem to exist as an autonomous functional unit; instead it is always associated with one of the other eight CRISPR subtypes. Cas, CRISPR-associated; CRISPR, clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat; RAMP, repeat-associated mysterious protein.

Table 2.

Cas protein characterization

| Protein | Organism | Gene locus | PDB iD* | Activity | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | PA14_33350 | 3GOD | Metal-dependent, dsDNA-specific endonuclease | 39 |

| Cas1 | Sulpholobus solfataricus | SSO1450 | N.D.‡ | Sequence-nonspecific, multi-site, high-affinity nucleic acid-binding protein | 85 |

| Cas2 | S. solfataricus | SSO1404 | 2I8E | ssRNA-specific endonuclease, preference for U-rich regions | 86 |

| Cas3 | S. solfataricus | SSO2001 | N.D.‡ | dsRNA and dsDNA endonuclease, preference for GC cleavage | 58 |

| Cas4§ | - | - | - | Belongs to the RecB family of exonucleases, suggesting a role in recombination | 21 |

| Cas5§ | - | - | - | Belongs to the RAMP family, no known or predicted activity | 21 |

| Cas6 | Pyrococcus furiosus | PF1131 | 3I4H | Metal-independent, CRISPR-specific endoribonuclease, belongs to the RAMP family | 21, 49 |

| Cse2 | Thermus thermophilus | TTHB189 | 2ZCA | No known or predicted activity | 87 |

| Cse3 | T. thermophilus | TTHB192 | 1WJ9 | Belongs to the RAMP family, no known or predicted activity | 21, 51 |

| Cmr5 | T. thermophilus | TTHB164 | 2ZOP | No known or predicted activity | 88 |

Protein database identification code.

Structure not determined.

No Cas4 or Cas5 orthologues have been characterized. Cas, CRISPR-associated; CRISPR, clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat; RAMP, repeat-associated mysterious protein.

The bioinformatic analysis of CRISPR loci in sequenced genomes has revealed an exceptional degree of genetic variability, perhaps reflecting the enormous diversity of mobile genetic elements to which bacteria and archaea are exposed. For example, it is common to find CRISPR loci belonging to different subtypes in one species, and the same subtypes can be found in phylo-genetically distant genomes. These and other findings suggest that CRISPR loci have themselves been acquired through HGT28,30–32, a hypothesis that is supported by the presence of CRISPR loci in many plasmids26,30.

Acquisition of new spacer sequences

At the molecular level, CRISPR function can be divided into three phases: the incorporation of new spacers into CRISPR arrays, the expression and processing of CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs), and CRISPR interference33. In the first phase, CRISPR loci incorporate additional spacers to programme their activity against invading plasmids and phages. This allows the cell to adapt rapidly to the invaders present in the environment and therefore we refer to it as the ‘adaptation’ phase of CRISPR function (FIG. 2). The information stored in spacers is then used to repel invaders during the ‘defence’ phase of CRISPR interference (described below).

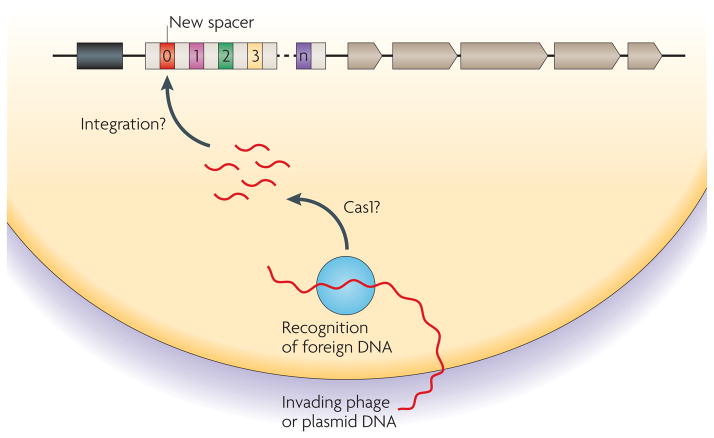

Figure 2. Acquisition of new repeat-spacer units.

During the adaptation phase of clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) immunity, new spacers derived from the invading DNA are incorporated into CRISPR loci. The mechanism of spacer acquisition is unknown but possibly uses the nuclease activity of CRISPR-associated 1 (Cas1) to generate short fragments of invading DNA. How the CRISPR machinery recognizes phage or plasmid DNA as invasive and therefore suitable for CRISPR locus incorporation is also unknown. The addition of new spacers is thought to involve an integration or conversion event and occurs at the leader-proximal end of the cluster. CRISPRs are shown as white boxes, the leader sequence is shown as a black box, non-repetitive spacers are shown as coloured boxes and cas genes are shown as grey arrows.

Adaptation to plasmids and predatory phages by spacer acquisition has been shown to occur readily in several species. In the course of studies of phage therapy for the prevention of tooth decay, M102 phages were introduced into rats to eliminate Streptococcus mutans, the principal aetiological agent of dental cavities. Bacteriophage-insensitive mutants (BIMs) were isolated that had added an M102-matching spacer sequence to one of the two CRISPR arrays in this species34. Similar adaptation can be induced in laboratory cultures by phage challenge of S. thermophilus22,35,36. These studies have determined that all new spacers are inserted at the leader end of the CRISPR array and that most integrations occur at the first position in the cluster. The loss of one or more repeat-spacer sequences has also been observed, which suggests that CRISPRs do not grow unchecked36,37. The addition of a single repeat-spacer unit is most common, but up to four new units have been detected35. Only two of the three CRISPR loci present in S. thermophilus have been shown to acquire new spacers36.

Active acquisition of new spacer sequences can also be detected by analysis of natural microbial populations. Metagenomic data (involving random sequencing of genomes from a whole community of microbes and phages) obtained from two sites within Richmond Mine (California, USA) over a period of months allowed the sequencing of distinct Leptospirillum sp. populations37. The populations were essentially identical except in the spacer content of the single CRISPR locus found. Spacer diversity was highly polarized: the distal (relative to the leader) half of the cluster was more conserved among both populations and the proximal half was much more divergent. The appearance of unique (new) spacers was accompanied by the loss of more conserved ones, again indicating that CRISPR growth is limited. These observations suggest a common ancestor for populations that diverged in their CRISPR content as they acquired new spacers to adapt to the distinct predatory phage populations in their new environments.

The molecular mechanism of spacer incorporation is unknown. Cas1 and Cas2 are dispensable for the function of pre-existing spacers in E. coli38, despite the apparent universality of these proteins in CRISPR–Cas systems, and therefore they are thought to participate in adaptation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cas1 is a sequence-nonspecific DNase that generates ~80-nt DNA fragments (see above) that have been suggested to reflect the initial sources of new 32-nt spacers39. How Cas1 might distinguish chromosomal from invasive DNA and how its presumed nucleolytic products integrate into CRISPR loci remain mysterious. Finally, a cas2 or csn2 gene that is associated with a CRISPR locus of S. thermophilus seems to be important for the acquisition of spacers in this bacterium, as its disruption prevents the generation of BIMs with novel spacers22.

The alignment of protospacer flanking sequences in phage genomes reveals the presence of short (2–3 nt) conserved regions that have been named ‘CRISPR motifs’ or ‘protospacer-adjacent motifs’ on either side of the protospacer sequence17,29,34,35,40,41. The presence of these motifs indicates that protospacers are not randomly selected and suggests that this conserved sequence may provide a recognition signal for the selection of target sequences that will become new spacers. In addition, phages can evade CRISPR immunity by mutating residues of the CRISPR motif35,41, which suggests a role for flanking sequences during the defence phase as well. Adaptation is one of the most intriguing and under-explored aspects of CRISPR biology.

Mechanisms of CRISPR interference

Once a spacer is established in a CRISPR locus, it provides specificity for the defence phase of the CRISPR pathway. Essential to this process is the generation of small crRNAs that are encoded by the repeats and spacers. To mount a successful defence, the CRISPR machinery must express and process CRISPR transcripts and use them to guide the interference machinery to invasive targets and obstruct the invasion (FIG. 3).

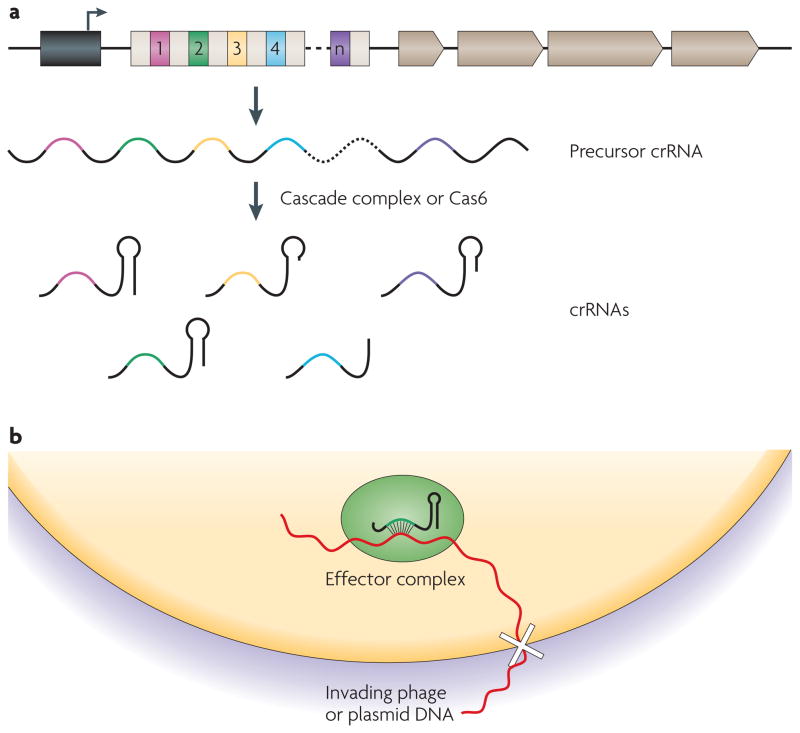

Figure 3. CRISPR interference.

a | In the interference or defence phase of clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) immunity, repeats and spacers are transcribed into a long precursor that is processed by a complex called CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defence (Cascade) in Escherichia coli or CRISPR-associated 6 (Cas6) in Pyrococcus furiosus, which generates small CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs). Processing occurs near the 3′ end of the repeat sequence, leaving a short (~8 nucleotides) repeat sequence 5′ of the crRNA spacer. crRNAs have a more heterogeneous 3′ terminus that sometimes contains the palindromic sequence of the downstream repeat and has the potential to form a stem–loop structure. CRISPR loci transcription seems to be constitutive and the leader sequence may act as a promoter (arrow). CRISPRs are shown as white boxes, the leader sequence is shown as a black box, non-repetitive spacers are shown as coloured boxes and cas genes are shown as grey arrows. b | RNAs serve as guides for an effector complex, presumably composed of Cas proteins, that recognizes invading DNA and blocks infection (white cross) by an unknown mechanism.

CRISPR transcription and processing

CRISPR-derived transcripts were first identified in small-RNA profiling studies of Archaeoglobus fulgidus42 and Sulpholobus solfataricus43. These studies suggested that the repeats and spacers are transcribed as a long precursor that is processed into small crRNAs, a hypothesis that has been confirmed by analysis of CRISPR transcription in E. coli38, Pyrococcus furiosus44, Sulpholobus acidocaldarius45 and Xanthomonas oyrzae41. Transcription is constitutive and unidirectional, but one possible exception to unidirectionality has been reported45. CRISPR transcription initiates at the end of the locus that contains the leader sequence, and the CRISPR promoter might even reside within the leader itself. Experiments in Thermus thermophilus suggest that the cyclic AMP regulator protein upregulates cas genes46,47 and that, at least in this bacterium, the CRISPR response may be governed by cAMP signal transduction. This pathway is activated during carbon source limitation, when the cell may be more susceptible to phage attack. In S. mutans, analysis of the transcriptome of a clpP protease mutant revealed increased expression of cas genes, which suggests the regulation of CRISPR loci48.

The processing of CRISPR precursor RNA (pre-crRNA) into small crRNAs is carried out by Cas proteins. The first analysis of the CRISPR molecular machinery was reported by Brouns et al.38 using the E. coli K12 CRISPR system, which includes the core Cas1–Cas3 and Cas5e proteins, as well as the subtype-specific Cse1–Cse4 proteins. Cse1–Cse4 and Cas5e always co-purify as a multiprotein complex named CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defence (Cascade). Wild-type cells expressed mature ~57-nt crRNAs (each with only a single spacer sequence), whereas cas5e (also known as casD) and cse3 (also known as casE) mutants accumulated pre-crRNA, indicating that Cas5e and Cse3 are required for crRNA processing. Purified Cascade, as well as Cse3 alone, was able to process an E. coli K12 pre-crRNA in vitro, and this analysis proved conclusively that processing occurs endonucleolytically at a specific site in each repeat (8 nt upstream of the spacer). Mature crRNAs were found to be associated with Cascade. Most crRNA 5′ ends coincided with the site of Cse3 processing, whereas the 3′ ends were more heterogeneous. Finally, the biological significance of Cascade was shown by the lack of CRISPR immunity in the absence of the functional complex. This work defined the role of a complex of E. coli Cas and Cse proteins in crRNA maturation and established that mature crRNAs are crucial for CRISPR interference.

Pre-crRNA processing has also been studied in P. furiosus. This archaeon contains seven CRISPR clusters associated with Cas proteins from the Cas module repeat-associated mysterious protein (RAMP), Apern and Tneap subtypes (TABLE 1). Carte et al.49 revealed Cas6 to be an endoribonuclease that requires specific repeat sequences. As in E. coli, cleavage occurs at a specific site 8 nt upstream of the spacer, and the resulting crRNAs are then trimmed in vivo at their 3′ but not 5′ ends44,50. Interestingly, P. furiosus cas6 encodes a protein that is structurally similar to T. thermophilus Cse3 (REFS 33,51). P. furiosus crRNAs encoded by spacers closer to the leader end (that is, those derived from the most recently encountered invaders) seem to accumulate to higher levels than those encoded further downstream. It is not known whether this reflects differences in crRNA transcription, processing, stability, or some combination thereof.

Together, these data support a model for the biogenesis of crRNAs in which Cas proteins cleave pre-crRNA precursors at a specific site in the repeat sequences (FIG. 3a), followed by uncharacterized 3′ trimming events. As a result, crRNAs have a well-defined 5′ end that begins with ~8 nt of the upstream repeat sequence (a pattern that is now known to extend to S. epidermidis crRNAs as well23) and a more heterogeneous 3′ end. Despite these advances, many aspects of crRNA generation remain to be studied. For example, how broadly do these conclusions extend among the different CRISPR–cas subtypes? Is the palindromic structure of repeats important for pre-crRNA processing? If so, are pre-crRNAs that contain non-palindromic repeats processed by a distinct set of Cas proteins? Is the heterogeneity of the 3′ termini functionally significant or is it an artefact of purification or cloning procedures?

Recognition of invading sequences

Once generated, crRNAs use their base-pairing potential to serve as guides for the recognition of the invasive target, presumably in the context of a crRNA–Cas ribonucleoprotein (crRNP) complex. Accumulated evidence shows that even a single spacer/target mismatch compromises CRISPR interference22,23,35. A study that analysed phages that evolved to evade CRISPR immunity in S. thermophilus35 found that out of 19 such phages, 8 contained a single mutation, 3 a double mutation and 1 a single-base deletion in the protospacer sequence. Interestingly, 7 phages carried substitutions in the downstream flanking sequence of the protospacer, within the CRISPR motif. Given the lengths of CRISPR spacers, equilibrium hybridization thermodynamics would seem to be insufficient for discrimination between perfect and singly mismatched targets, suggesting that crRNA/target mispairing may be actively sensed by the CRISPR–Cas machinery.

Several lines of evidence indicate that the CRISPR machinery in numerous species recognizes DNA rather than RNA targets (FIG. 3b). Bioinformatic analysis of the natural target distribution in several phage genomes shows that both the sense and antisense strands contain protospacers. This has been shown in viruses and plasmids of S. solfataricus20,52, several other crenarchaeal acidothermophiles29, S. thermophilus35,36, S. mutans34, Y. pestis53 and X. oyrzae41. In X. oyrzae, a protospacer was even identified in an apparently intergenic region of the phage genome41. Engineered crRNAs complementary to either sense or antisense sequences in the λ phage genome can also confer interference in E. coli38. These observations, combined with the apparent unidirectionality of most CRISPR transcription23,38,44, imply that crRNAs must be able to recognize antisense sequences, which suggests that dsDNAs but not mRNAs are viable candidate targets. In addition, no spacers that match RNA viruses have been found to date39,40, although this could be a consequence of the scarcity of RNA phage genome sequences or an inability of the CRISPR machinery to incorporate spacers from these phages. Finally, the existence of many natural protospacers in phage genes that are expressed late in the lytic cycle29,35,41 (when host viability is already compromised)54 would be difficult to reconcile with an RNA targeting mechanism.

More direct evidence for DNA targeting was obtained in S. epidermidis23. A clinical isolate of this bacterium (S. epidermidis RP62A55) harbours a single CRISPR locus with only three spacers. One cognate protospacer is found in the nickase (nes) gene, which is present in most staphylococcal conjugative plasmids. These plasmids transfer from a donor to a recipient bacterium and carry all of the genes that encode the mobilization machinery. Transfer begins with the essential cleavage of one strand of the oriT locus in the donor cell by the nes protein56, and successful conjugation does not require nes mRNA expression in the recipient. Conjugative transfer was tested using wild-type S. epidermidis RP62A and a ΔCRISPR mutant as recipients, and sequence-dependent interference was observed only in the former. This result strongly supports nes DNA targeting in the recipient, as the essential nes mRNA and the CRISPR machinery are physically separated in donor and recipient cells, respectively. DNA targeting was further corroborated by the interruption of the nes protospacer with a self-splicing intron. In this scenario, the target sequence is permanently disrupted in the plasmid DNA but is then reconstituted only in the spliced nes mRNA. Conjugation efficiencies into and out of wild-type S. epidermidis were similar to those of Δ CRISPR mutants, indicating that CRISPR interference requires an intact target in the nes DNA, but not in the nes mRNA. DNA targeting in S. epidermidis, and probably other species as well, represents a fundamental distinction between CRISPR interference and RNAi (BOX 1).

Box 1. CRISPR interference and eukaryotic RNA silencing: how similar are they?

In eukaryotes, RNA interference (RNAi) and related pathways use 20–30-nucleotide short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) and piwi-interfering RNAs (piRNAs) as guides for gene regulation and genome defence81–84. The nature of clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) interference immediately raises questions about its relationship to RNAi. Although the picture is still evolving, clear similarities and differences are emerging. The similarities are indeed intriguing: both block gene function in a programmable, sequence-directed manner and use RNAs to guide an effector apparatus to the target. The guide RNAs are processed from longer precursors38,49 and incorporate sequences that are ultimately derived from invasive nucleic acids17–19,22. Both sets of pathways have adaptive and heritable components that are used to establish recoverable genomic records of past invasions22,26; the latter similarity is particularly obvious for the piRNA branch of eukaryotic silencing82.

Despite these analogies, it is increasingly clear that CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) and eukaryotic RNA silencing are not homologous. First and foremost, the protein machineries are completely distinct21,28. Unlike siRNAs and miRNAs, crRNAs arise from single-stranded precursors23,38,44,49 and do not seem to be post-transcriptionally amplified. Furthermore, the eukaryotic pathways recognize other RNAs, whereas crRNA targeting of DNA has been demonstrated during CRISPR interference23. (However, in vitrotargeting of RNAs by a Pyrococcus furiosuscrRNA–Cas ribonucleoprotein (crRNP) complex has been documented50, raising the possibility that RNAi may have greater functional analogies with some CRISPR systems than with others.) Whereas eukaryotes use RNAi-related pathways to regulate endogenous genes, functions for crRNAs beyond invader defence are less clear. Finally, in RNAi, the RNA guides can be extracted directly from invasive nucleic acids, so the capacity for mutational evasion by the invader is limited. By contrast, CRISPR sequence determinants must first become encoded in the host genome before they are accessible in defence, and this is a low-frequency event22,26; phages and plasmids therefore have greater potential for mutational evasion ‘on the fly.’

Recognition of RNA targets?

The possibility of RNA targeting by some CRISPR systems has been raised by recent biochemical characterization of crRNP complexes from P. furiosus50. Purified crRNPs were found to contain a set of Cas proteins, Cmr1–Cmr6 (all of which are encoded by the apparently non-autonomous RAMP module subtype genes (TABLE 1)). Nucleolytic assays revealed that the complex has crRNA-guided endoribonuclease activity, but no DNA cleavage was detected. RNA cleavage generated 3′-phosphate and 5′-hydroxyl ends and occurred at a fixed distance (14 nt) from the target nucleotide opposite the 3′-terminal base of the crRNA. This activity was reconstituted with synthetic crRNAs, as well as purified recombinant Cmr proteins. These results indicate that crRNA-directed RNA cleavage can occur in P. furiosus (and perhaps other species expressing the RAMP module proteins). Functional tests of this model during interference in vivo have not yet been possible. The hypothesis that CRISPR interference occurs by RNA targeting in this organism leads to the strong prediction that P. furiosus phage protospacers will differ from those of other characterized CRISPRs in several ways, including orientation dependence (to enable targeting of sense transcripts), insensitivity to protospacer intron disruption, and under-representation in genes expressed late in the lytic cycle. In addition, RAMP subtype CRISPR systems may target RNA bacteriophages. None of the spacer sequences found in the P. furiosus CRISPRs have matches in Genbank, so these predictions cannot yet be assessed.

Discriminating between self and non-self

DNA targeting during CRISPR immunity raises an issue that is faced by all immune systems: how to recognize self from non-self to thwart invasions without triggering autoimmunity. Because the sequence match between the spacer in the crRNA and the target in the invasive DNA also exists between the crRNA and the CRISPR locus that encodes it, there must be a mechanism that enables CRISPR systems to avoid targeting their own DNA. Recently, we showed that CRISPRs provide the means to exclude self DNA from targeting in S. epidermidis. Specifically, compensatory mutagenic analyses of crRNAs and their DNA targets revealed that self and foreign DNA are differentially recognized by the crRNA outside the protospacer57: the ~8 nt of repeat sequence at the crRNA 5′ terminus pairs only with CRISPR DNA. In bona fide targets, the absence of this complementarity licenses interference (FIG. 4). Although this mechanism has only been documented thus far in S. epidermidis, differential base pairing outside the spacer sequence is a built-in capability of all CRISPR systems. It may therefore provide a broadly applicable means of discriminating self from non-self during the CRISPR immune response.

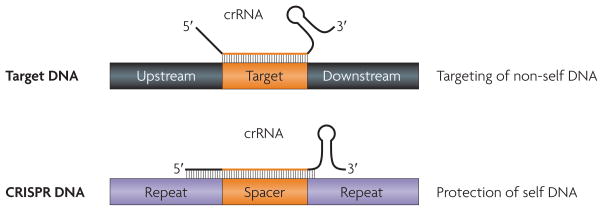

Figure 4. self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR immunity.

The spacer sequences of clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNAs (crRNAs) have perfect complementarity with the CRISPR locus from which they are transcribed, which confers the potential to target CRISPR DNA. In Staphylococcus epidermidis, this autoimmune response is prevented by differential base pairing of spacer/target 5′ flanking sequences57. A similar role for 3′ flanking sequences in other organisms cannot be excluded. Whereas interference requires crRNA/target mismatches outside the spacer sequence, complementarity between crRNA and repeat sequences in the CRISPR DNA prevents autoimmunity. The figure is adapted, with permission, from Nature REF. 57 © (2010) Macmillan Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Obstruction of nucleic acid invasion

The specific molecular events that obstruct invasion during CRISPR interference in vivo are poorly understood. A study in S. thermophilus showed that CRISPR-directed immunity does not prevent phage adsorption or DNA injection, is independent of restriction–modification systems, and is not associated with the high incidence of cell death that would be expected for an abortive infection mechanism35. If RNA targeting by the Cmr1–Cmr2–Cmr3–Cmr4–Cmr5–Cmr6 complex is validated as an in vivo mechanism of interference in P. furiosus, this will point towards mRNA destruction as an inhibitory event in that case. As for DNA targeting in S. epidermidis, E. coli and other systems from the Mtube and Ecoli Cas subtypes (TABLE 1), the simplest scenario would likewise involve the destruction of the invasive DNA, although this has not been observed directly. However, this possibility is consistent with the emergence of the histidine-aspartate nuclease (HD nuclease) domain-containing Cas3 protein as the leading candidate effector protein in E. coli. Cas3 is dispensable for crRNA processing, accumulation or Cascade association but is nonetheless essential for interference38. Cas3 in E. coli also carries an apparent ATP-dependent helicase domain that, if functional, could perhaps act as a target DNA unwindase to enable protospacer hybridization with the crRNA. Intriguingly, biochemical analysis of an S. solfataricus Cas3 orthologue58 revealed nuclease activity that was specific for double-stranded substrates (both RNA and DNA). Not all CRISPR–cas subtypes contain cas3 or are associated with the RAMP module Cmr proteins, which indicates that additional candidate effector proteins must exist.

Our understanding of CRISPR defence mechanisms is in its infancy. Nonetheless, these first molecular analyses have revealed that the exceptional diversity of CRISPRs and associated genes is reflected at the biochemical level: multiple activities have been found for different Cas proteins, distinct Cas proteins participate in crRNA biogenesis and target recognition, and differences may even exist in the nature of the molecular targets of CRISPR interference.

CRISPRs and the evolution of bacterial pathogens

HGT is a major source of genetic variability for bacterial evolution1,2. The ability of CRISPR systems to limit phage infection22 and plasmid conjugation23 has been proven. It remains to be determined whether CRISPRs constitute an effective barrier against natural DNA transformation, although it was shown that CRISPRs can prevent the electroporation of plasmid DNA23. Therefore, CRISPR systems interfere with at least two major routes of HGT and thus have an important role in bacterial evolution.

HGT is the major mechanism for the acquisition of antimicrobial resistance genes and genes that encode virulence factors by bacterial pathogens. A crucial health-care issue is the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin- resistant S. aureus (VRSA)59 strains, the genesis of which is directly linked to the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes by plasmid conjugation60. Likewise, sequencing of the highly virulent MRSA strain USA300 indicated that HGT has allowed the acquisition of elements that encode resistance and virulence determinants that enhance fitness and pathogenicity61. S. aureus and S. epidermidis strains are the most common causes of nosocomial infections62–64, and mobile genetic elements can spread from one species to the other61. CRISPR interference has been found to limit conjugation of the pG0400 plasmid from S. aureus to S. epidermidis in the laboratory23 and possibly constitutes a natural barrier to the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

Upon infection of the bacterial host, phages can undergo either lytic or lysogenic replication cycles. In the lysogenic cycle, a temperate phage integrates its genome into the bacterial chromosome, becoming an inheritable prophage. It has been long known that prophage-encoded genes have an important role in the virulence of pathogenic strains65. For example, many bacterial toxins reside in prophages found in the genomes of Corynebacterium diphteriae, Clostridium botulinum, Vibrio cholerae, E. coli, Streptococcus pyogenes and S. aureus. The contribution of prophages to the virulence of S. pyogenes (group A Streptococcus (GAS)) is well studied66. Increases in the frequency and severity of infection, as well as the complex array of GAS clinical presentations, have been suggested to be driven by phage-encoded virulence factors. Of the 13 GAS sequenced strains, 8 harbour CRISPR systems and contain few or no prophages24. Conversely, strains that lack CRISPRs are polylysogens. Moreover, many CRISPR spacers match sequences of prophages that are integrated into other strains — that is, there is a mutually exclusive relationship between CRISPR spacers and prophages — which suggests that CRISPR immunity can prevent not only phage lysis but also lysogenesis17. Therefore, CRISPR immunity against lysogenic bacteriophages may interfere with the spread of virulence factors among pathogens.

Finally, many of the virulence plasmids that are required for establishing a successful infection by a number of bacterial pathogens are believed to have diverged from conjugative plasmids67. Also, pathogenicity islands are flanked by transposable elements and therefore can transfer between different species by ‘hitch-hiking’ on conjugative plasmids and temperate phages68. The prevention of conjugation and phage infection by CRISPRs suggests a capacity for these loci to reduce the acquisition of genetic traits that allow bacteria to become virulent.

CRISPRs and the evolution of bacteriophages

Bacteriophages are the most numerous entities in the biosphere, and bacteria and archaea have developed a number of mechanisms of phage defence69, CRISPRs being the most recently discovered. Each of these defence systems imposes a selective pressure that results in the evolution of new bacteriophage variants that can overcome these barriers, and several different mechanisms for evading CRISPR immunity have been described. Phages can overcome S. thermophilus CRISPR interference by acquiring a single mutation in or around the target sequence22,35. Also, the passage of SIRV1 phages through Sulfolobus islandicus hosts results in the accumulation of 12 nt-long indels throughout the phage genome70, an observation that led to speculation that this could be a strategy adopted by crenarchaeal phages to bypass CRISPR defences71.

In natural environments in which the host cell is challenged by many phage variants at the same time, recombination seems to be selected for to counteract CRISPR immunity. Recently, Anderson and Banfield26 used large metagenomic data sets collected from two acid mine biofilms to assemble partial genomic sequences from five different sets of viral populations. To do this, the authors cleverly exploited the sequence information and diversity contained in the CRISPR spacers to identify other non-CRISPR sequences that matched the spacers and were therefore likely to be of viral origin. Analysis of the different phage population genomes revealed a high level of sequence variation (as a function of both time and locale), which suggests extensive homologous recombination. The reshuffling of polymorphic loci yields sequence blocks no longer than 25 nt shared between individual phages — enough to escape targeting by the 28- to 54-nt Leptospirillum sp. CRISPR spacers. This constitutes a better CRISPR-evading strategy than mutation, as recombination of previously established polymorphisms presents less risk of altering protein function. It is currently unknown whether any phages encode factors that can actively target the CRISPR machinery to prevent immunity. However, it is clear that CRISPR interference contributes to the evolution of bacteria and archaea and also has profound effects on the evolution of bacteriophages.

CRISPR-based technologies

CRISPR-based technological applications exploit the unique structure and function of these loci72. Long before the elucidation of CRISPR function, the variability in the spacer content of the cluster was used to simultaneously detect and identify strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnostic purposes and epidemiological studies73. This genotyping method was named spacer oligotyping or ‘spoligotyping’. It is widely used for the identification of M. tuberculosis strains74 and has been applied to other organisms as well75,76.

The most important current application of CRISPR interference is the generation of phage-resistant strains of domesticated bacteria for the dairy industry22,36,77. Phage infection of dairy starter cultures disrupts normal fermentation cycles, stalls the manufacturing chain and decreases the quality of the finished product78. S. thermophilus is a key starter culture strain involved in the acidification of milk. The natural acquisition of new spacers observed in this bacterium is an exceptional tool for the control of phage infection in the dairy industry, as it allows the isolation of strains that are resistant to multiple bacteriophages but that still retain the same starter culture properties. Because genetic engineering is not used, the resulting products do not require labelling as ‘genetically modified’.

Other potential applications of CRISPRs await further development to determine their plausibility. For example, a crRNP complex in P. furiosus50 can cleave a target RNA at a specific site dictated by the sequence of the crRNA guide. This activity could in principle have applications in molecular biology to specifically cleave RNA molecules in vitro, and could be extended to DNA molecules if other crRNP complexes are proven to have DNA endonuclease activity. Finally, CRISPR interference towards plasmid conjugation23 opens the possibility of manipulating CRISPR systems to limit the dissemination of antibiotic-resistant strains in hospitals. Further research efforts will be required to explore the potential utility of this technology.

Future directions

Despite the progress made in the understanding of CRISPR function, many central aspects remain obscure. An important question is whether CRISPRs have other physiological functions besides the prevention of phage infection and plasmid conjugation. Intriguingly, there are reports of cas genes that are involved in biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa79 and in the development of fruiting bodies in Myxococcus xanthus80; more research will be needed to determine the relationship between these phenomena and CRISPR function.

Mechanistic aspects of CRISPR biology need attention as well. How new spacers are acquired is for the most part unknown. The events that ultimately lead to prevention of phage infection or plasmid transfer also await elucidation; degradation of the invading DNA or RNA during infection in vivo seems to be a likely mechanism, but this remains to be demonstrated. The complexities of CRISPR systems — with their 45 families of Cas proteins — present both challenges and opportunities for CRISPR research, particularly regarding the mechanistic similarities and differences among subtypes. Furthermore, the complex nature of CRISPR immunity raises the question of whether non-Cas host factors function in adaptation or interference, a possibility that so far has not been explored. Over the coming years we anticipate vigorous biochemical, genetic and genomic research into CRISPR biology that will expand the repertoire of experimental systems and clarify many of these issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Terns and M. Terns for communicating results before publication. L.A.M. is a fellow of The Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research. This work was supported by a grant from the US National Institutes of Health to E.J.S.

- Transformation

Genetic alteration of a cell resulting from the acquisition of genes from free DNA molecules in the surrounding environment

- Conjugation

The transfer of genetic information from a donor to a recipient cell by a conjugative or mobile genetic element, often a conjugative plasmid

- Bacteriophage

(Also abbreviated to ‘phage’.) A virus that infects bacteria. Virulent phages kill the host (lytic infection cycle), whereas temperate phages can integrate into the host chromosome (lysogenic cycle), becoming a prophage

- Transduction

The transfer of genetic information from one bacterial or archaeal cell to another by a phage particle containing chromosomal DNA

- DNA restriction

The destruction of foreign dsDNA by a restriction endonuclease. The protection of self DNA from restriction is achieved by DNA methylation

- Surface exclusion

A process that bars conjugative transfer of a plasmid into recipient cells that already harbour a related plasmid

- RNA interference

A set of related pathways in eukaryotic cells that use small (20–30 nucleotides) RNAs to regulate the expression or function of cognate sequences

- Protospacer

Phage or plasmid sequences that match one or more clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) spacer sequences and are targeted during CRISPR interference

- Dyad symmetry

A twofold rotational symmetry relationship (in this case, a DNA arrangement in which a 5′→3′ sequence on one strand is juxtaposed with the same 5′→3′ sequence on the opposite strand). Transcripts from such regions have the capacity to form stem–loop structures

- Crenarchaeal

Referring to members of the Crenarchaeota phylum, which is composed mainly of thermophilic archaeal organisms

- Histidine-aspartate nuclease

A divalent-metal-dependent phosphohydrolase with a conserved histidine-aspartate motif

- Unwindase

Enzyme that uses the free energy of NTP binding and hydrolysis to drive the separation of complementary RNA or DNA strands

- Virulence factor

A gene responsible for the production of a molecule that contributes to the establishment of disease by bacterial pathogens

- Polylysogen

A lysogen is a bacterium that has a prophage integrated into its chromosome. A polylysogen contains many prophage sequences in its genome

- Virulence plasmid

A plasmid that carries virulence factor genes or pathogenicity islands

- Pathogenicity island

Genomic islands that contain genes that are required for virulence. These islands are usually absent from non-pathogenic organisms and are acquired by horizontal gene transfer

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene casD|casE|clpP

Entrez Nucleotide: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore iap|nes

InterPro: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro Cas3

Pfam: http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk Cas1|Cas2

FURTHER INFORMATION

Luciano A. Marraffini’s homepage: http://groups.bmbcb.northwestern.edu/sontheimer/Marraffini.php

Erik J. Sontheimer’s homepage: http://groups.bmbcb.northwestern.edu/sontheimer/index.php

CRISPR database: http://crispr.u-psud.fr/crispr

GenBank: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank

Integrated Microbial Genomes data management system: http://img.jgi.doe.gov

All links ARe Active in the Online PDF

Contributor Information

Luciano A. Marraffini, Email: l-marraffini@northwestern.edu.

Erik J. Sontheimer, Email: erik@northwestern.edu.

References

- 1.Nakamura Y, Itoh T, Matsuda H, Gojobori T. Biased biological functions of horizontally transferred genes in prokaryotic genomes. Nature Genet. 2004;36:760–766. doi: 10.1038/ng1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas CM, Nielsen KM. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:711–721. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5429–5433. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5429-5433.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakata A, Amemura M, Makino K. Unusual nucleotide arrangement with repeated sequences in the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3553–3556. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3553-3556.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermans PW, et al. Insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot-spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2695–2705. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2695-2705.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mojica FJ, Ferrer C, Juez G, Rodriguez-Valera F. Long stretches of short tandem repeats are present in the largest replicons of the Archaea Haloferax mediterranei and Haloferax volcanii and could be involved in replicon partitioning. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masepohl B, Gorlitz K, Bohme H. Long tandemly repeated repetitive (LTRR) sequences in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp PCC 7120. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1307:26–30. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(96)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoe N, et al. Rapid molecular genetic subtyping of serotype M1 group A Streptococcus strains. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:254–263. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bult CJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klenk HP, et al. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson KE, et al. Evidence for lateral gene transfer between Archaea and Bacteria from genome sequence of Thermotoga maritima. Nature. 1999;399:323–329. doi: 10.1038/20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sensen CW, et al. Completing the sequence of the Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 genome. Extremophiles. 1998;2:305–312. doi: 10.1007/s007920050073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawarabayasi Y, et al. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic hyper-thermophilic crenarchaeon, Aeropyrum pernix K1. DNA Res. 1999;6:83–101. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawarabayasi Y, et al. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyper-thermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. DNA Res. 1998;5:55–76. doi: 10.1093/dnares/5.2.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Soria E, Juez G. Biological significance of a family of regularly spaced repeats in the genomes of Archaea, Bacteria and mitochondria. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:244–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansen R, Embden JD, Gaastra W, Schouls LM. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1565–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. This paper noted the existence of cas protein-coding genes associated with CRISPR loci. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology. 2005;151:2551–2561. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. This paper, along with references 18 and 19, documented the sequence matches between CRISPR spacers and phage or plasmid sequences, thereby suggesting a role for CRISPR loci in defence against invasive DNA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Garcia-Martinez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pourcel C, Salvignol G, Vergnaud G. CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies. Microbiology. 2005;151:653–663. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lillestøl RK, Redder P, Garrett RA, Brugger K. A putative viral defence mechanism in archaeal cells. Archaea. 2006;2:59–72. doi: 10.1155/2006/542818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makarova KS, Grishin NV, Shabalina SA, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. A putative RNA-interference-based immune system in prokaryotes: computational analysis of the predicted enzymatic machinery, functional analogies with eukaryotic RNAi, and hypothetical mechanisms of action. Biol Direct. 2006;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrangou R, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. This study provided the first experimental demonstration of CRISPR interference, documented the acquisition of novel spacers in response to phage infection and showed that cas gene function is essential for CRISPR function in defence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science. 2008;322:1843–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.1165771. This paper showed that CRISPR interference also blocks conjugation, and demonstrated that DNA rather than RNA is the molecular target of the pathway in S. epidermidis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C. The CRISPRdb database and tools to display CRISPRs and to generate dictionaries of spacers and repeats. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunin V, Sorek R, Hugenholtz P. Evolutionary conservation of sequence and secondary structures in CRISPR repeats. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R61. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson AF, Banfield JF. Virus population dynamics and acquired virus resistance in natural microbial communities. Science. 2008;320:1047–1050. doi: 10.1126/science.1157358. This study used metagenomics to profile CRISPR spacer composition and phage sequences in a spatially and temporally resolved fashion to analyse host–pathogen interactions in a natural microbial population. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heidelberg JF, Nelson WC, Schoenfeld T, Bhaya D. Germ warfare in a microbial mat community: CRISPRs provide insights into the co-evolution of host and viral genomes. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haft DH, Selengut J, Mongodin EF, Nelson KE. A guild of 45 CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein families and multiple CRISPR/Cas subtypes exist in prokaryotic genomes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010060. This work, along with reference 21, examined CRISPR and cas phylogenetics and established the existence of distinct subtypes of CRISPR–cas loci and multiple families of Cas proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah SA, Hansen NR, Garrett RA. Distribution of CRISPR spacer matches in viruses and plasmids of crenarchaeal acidothermophiles and implications for their inhibitory mechanism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:23–28. doi: 10.1042/BST0370023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godde JS, Bickerton A. The repetitive DNA elements called CRISPRs and their associated genes: evidence of horizontal transfer among prokaryotes. J Mol Evol. 2006;62:718–729. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makarova KS, Aravind L, Grishin NV, Rogozin IB, Koonin EV. A DNA repair system specific for thermophilic Archaea and Bacteria predicted by genomic context analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:482–496. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.2.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portillo MC, Gonzalez JM. CRISPR elements in the Thermococcales: evidence for associated horizontal gene transfer in Pyrococcus furiosus. J Appl Genet. 2009;50:421–430. doi: 10.1007/BF03195703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Oost J, Jore MM, Westra ER, Lundgren M, Brouns SJ. CRISPR-based adaptive and heritable immunity in prokaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Ploeg JR. Analysis of CRISPR in Streptococcus mutans suggests frequent occurrence of acquired immunity against infection by M102-like bacteriophages. Microbiology. 2009;155:1966–1976. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.027508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deveau H, et al. Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1390–1400. doi: 10.1128/JB.01412-07. This paper, along with reference 40, reported the existence of short, conserved ‘CRISPR motifs’ or ‘protospacer-adjacent motifs’ that flank target protospacers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horvath P, et al. Diversity, activity, and evolution of CRISPR loci in Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1401–1412. doi: 10.1128/JB.01415-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyson GW, Banfield JF. Rapidly evolving CRISPRs implicated in acquired resistance of microorganisms to viruses. Environ Microbiol. 2007;10:200–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brouns SJ, et al. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008;321:960–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1159689. This report, along with reference 49, documented and characterized the crRNA processing pathway; Brouns et al. also proved that crRNAs are essential for CRISPR interference in E. coli, implicated Cas3 as an effector protein in this process and pointed towards DNA as a likely target. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiedenheft B, et al. Structural basis for DNase activity of a conserved protein implicated in CRISPR-mediated genome defense. Structure. 2009;17:904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.019. This study reported the first crystal structure of a protein (Cas1) that is universal among CRISPR–cas loci and documented its nuclease activity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Garcia-Martinez J, Almendros C. Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system. Microbiology. 2009;155:733–740. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.023960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Semenova E, Nagornykh M, Pyatnitskiy M, Artamonova II, Severinov K. Analysis of CRISPR system function in plant pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;296:110–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang TH, et al. Identification of 86 candidates for small non-messenger RNAs from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7536–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112047299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang TH, et al. Identification of novel non-coding RNAs as potential antisense regulators in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:469–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hale C, Kleppe K, Terns RM, Terns MP. Prokaryotic silencing (psi)RNAs in Pyrococcus furiosus. RNA. 2008;14:2572–2579. doi: 10.1261/rna.1246808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lillestøl RK, et al. CRISPR families of the crenarchaeal genus Sulfolobus: bidirectional transcription and dynamic properties. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:259–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agari Y, et al. Transcription profile of Thermus thermophilus CRISPR systems after phage infection. J Mol Biol. 2010;395:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shinkai A, et al. Transcription activation mediated by a cyclic AMP receptor protein from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3891–3901. doi: 10.1128/JB.01739-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chattoraj P, Banerjee A, Biswas S, Biswas I. ClpP of Streptococcus mutans differentially regulates expression of genomic islands, mutacin production and antibiotics tolerance. J Bacteriol. 2009 Dec 28; doi: 10.1128/JB.01350-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carte J, Wang R, Li H, Terns RM, Terns MP. Cas6 is an endoribonuclease that generates guide RNAs for invader defense in prokaryotes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3489–3496. doi: 10.1101/gad.1742908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hale CR, et al. RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA–Cas protein complex. Cell. 2009;139:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.040. This paper characterized P. furiosus crRNP components, reported the first high-throughput profiling of a crRNA population and demonstrated crRNA-directed RNA cleavage by a crRNP complex in vitro. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ebihara A, et al. Crystal structure of hypothetical protein TTHB192 from Thermus thermophilus HB8 reveals a new protein family with an RNA recognition motif-like domain. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1494–1499. doi: 10.1110/ps.062131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Redder P, et al. Four newly isolated fuselloviruses from extreme geothermal environments reveal unusual morphologies and a possible interviral recombination mechanism. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2849–2862. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cui Y, et al. Insight into microevolution of Yersinia pestis by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller ES, et al. Bacteriophage T4 genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:86–156. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.86-156.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gill SR, et al. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2426–2438. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2426-2438.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Climo MW, Sharma VK, Archer GL. Identification and characterization of the origin of conjugative transfer (oriT) and a gene (nes) encoding a single-stranded endonuclease on the staphylococcal plasmid pGO1. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4975–4983. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4975-4983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity. Nature. 2010 Jan 13; doi: 10.1038/nature08703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han D, Krauss G. Characterization of the endonuclease SSO2001 from Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furuya EY, Lowy FD. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in the community setting. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weigel LM, et al. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;302:1569–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diep BA, et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367:731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lim SM, Webb SA. Nosocomial bacterial infections in intensive care units. I: Organisms and mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:887–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.von Eiff C, Peters G, Heilmann C. Pathogenesis of infections due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:677–685. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brussow H, Canchaya C, Hardt WD. Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:560–602. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Banks DJ, Beres SB, Musser JM. The fundamental contribution of phages to GAS evolution, genome diversification and strain emergence. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:515–521. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu X, Van der Auwera G, Timmery S, Zhu L, Mahillon J. Distribution, diversity, and potential mobility of extrachromosomal elements related to the Bacillus anthracis pXO1 and pXO2 virulence plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:3016–3028. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02709-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hacker J, Kaper JB. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:641–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sturino JM, Klaenhammer TR. Bacteriophage defense systems and strategies for lactic acid bacteria. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2004;56:331–378. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(04)56011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng X, Kessler A, Phan H, Garrett RA, Prangishvili D. Multiple variants of the archaeal DNA rudivirus SIRV1 in a single host and a novel mechanism of genomic variation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:366–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vestergaard G, et al. Stygiolobus rod-shaped virus and the interplay of crenarchaeal rudiviruses with the CRISPR antiviral system. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6837–6845. doi: 10.1128/JB.00795-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sorek R, Kunin V, Hugenholtz P. CRISPR — a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kamerbeek J, et al. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:907–914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.907-914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Driscoll JR. Spoligotyping for molecular epidemiology of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;551:117–128. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-999-4_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mokrousov I, Limeschenko E, Vyazovaya A, Narvskaya O. Corynebacterium diphtheriae spoligotyping based on combined use of two CRISPR loci. Biotechnol J. 2007;2:901–906. doi: 10.1002/biot.200700035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vergnaud G, et al. Analysis of the three Yersinia pestis CRISPR loci provides new tools for phylogenetic studies and possibly for the investigation of ancient DNA. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;603:327–338. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72124-8_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mills S, et al. CRISPR analysis of bacteriophage-insensitive mutants (BIMs) of industrial Streptococcus thermophilus — implications for starter design. J Appl Microbiol. 2009 Jul 20; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mc Grath S, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. Bacteriophages in dairy products: pros and cons. Biotechnol J. 2007;2:450–455. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zegans ME, et al. Interaction between bacteriophage DMS3 and host CRISPR region inhibits group behaviors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:210–219. doi: 10.1128/JB.00797-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Viswanathan P, Murphy K, Julien B, Garza AG, Kroos L. Regulation of dev, an operon that includes genes essential for Myxococcus xanthus development and CRISPR-associated genes and repeats. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3738–3750. doi: 10.1128/JB.00187-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Malone CD, Hannon GJ. Small RNAs as guardians of the genome. Cell. 2009;136:656–668. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moazed D. Small RNAs in transcriptional gene silencing and genome defence. Nature. 2009;457:413–420. doi: 10.1038/nature07756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siomi H, Siomi MC. On the road to reading the RNA-interference code. Nature. 2009;457:396–404. doi: 10.1038/nature07754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Han D, Lehmann K, Krauss G. SSO1450 — a CAS1 protein from Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 with high affinity for RNA and DNA. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1928–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beloglazova N, et al. A novel family of sequence-specific endoribonucleases associated with the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20361–20371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803225200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Agari Y, Yokoyama S, Kuramitsu S, Shinkai A. X-ray crystal structure of a CRISPR-associated protein, Cse2, from Thermus thermophilus HB8. Proteins. 2008;73:1063–1067. doi: 10.1002/prot.22224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sakamoto K, et al. X-ray crystal structure of a CRISPR-associated RAMP superfamily protein, Cmr5, from Thermus thermophilus HB8. Proteins. 2009;75:528–532. doi: 10.1002/prot.22358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]