Abstract

Context: Hypovitaminosis D and depressive symptoms are common conditions in older adults.

Objective: We examined the relationship between 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and depressive symptoms over a 6-yr follow-up in a sample of older adults.

Design and Setting: This research is part of a population-based cohort study (InCHIANTI Study) in Tuscany, Italy.

Participants: A total of 531 women and 423 men aged 65 yr and older participated.

Main Outcome Measure: Serum 25(OH)D was measured at baseline. Depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline and at 3- and 6-yr follow-ups using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). Depressed mood was defined as CES-D of 16 or higher. Analyses were stratified by sex and adjusted for relevant biomarkers and variables related to sociodemographics, somatic health, and functional status.

Results: Women with 25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/liter compared with those with higher levels experienced increases in CES-D scores of 2.1 (P = 0.02) and 2.2 (P = 0.04) points higher at, respectively, 3- and 6-yr follow-up. Women with low vitamin D (Vit-D) had also significantly higher risk of developing depressive mood over the follow-up (hazard ratio = 2.0; 95% confidence interval = 1.2–3.2; P = 0.005). In parallel models, men with 25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/liter compared with those with higher levels experienced increases in CES-D scores of 1.9 (P = 0.01) and 1.1 (P = 0.20) points higher at 3- and 6-yr follow-up. Men with low Vit- D tended to have higher risk of developing depressed mood (hazard ratio = 1.6; 95% confidence interval = 0.9–2.8; P = 0.1).

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that hypovitaminosis D is a risk factor for the development of depressive symptoms in older persons. The strength of the prospective association is higher in women than in men. Understanding the potential causal pathway between Vit- D deficiency and depression requires further research.

Hypovitaminosis D is a risk factor for the development of depressive symptoms in older persons.

Hypovitaminosis D is highly prevalent in older persons as a result of reduced capacity of the skin to produce vitamin D (Vit-D), reduced sunlight exposure due to decreased outdoor activity, and reduced vitamin dietary intake (1). In older adults, Vit-D deficiency has been linked to poor health outcomes, such as fractures (2), poor physical function (3), frailty (4), sarcopenia (5), pain (6), nursing home admission (7), mortality (8) and chronic diseases such as osteoporosis, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, autoimmune, and infectious diseases (9,10,11).

Chronic depressive syndromes are also very common in older persons, especially in those affected by chronic medical illness, and strongly affect the risk of developing disability and death (12). It has been hypothesized that hypovitaminosis D may contribute to late life depression (13,14,15). However, only a few studies with limited sample size have examined the association between Vit-D and depression, with conflicting findings (15,16,17,18,19). One large population-based cohort study (20) found that the levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] were lower in participants with minor and major depression than in controls. In this study, we examined the longitudinal relationship between Vit-D and depressive symptoms over a 6-yr follow-up in a representative group of older adults. We hypothesized that participants with lower 25(OH)D levels at baseline would experience a steeper increase in severity of depressive symptoms and would be significantly more likely to develop clinically relevant depressed mood than those with higher 25(OH)D. Demonstrating a time sequence between Vit-D deficiency and depression would support further the hypothesis of a causal pathway that can be targeted for intervention.

Subjects and Methods

Study population

Participants were part of the InCHIANTI (Invecchiare in Chianti, aging in the Chianti area) Study, a prospective population-based study of older persons in Tuscany (Italy) designed to investigate factors contributing to decline in mobility in later life. A description of the study rationale, design, and method is given elsewhere (21). Briefly, in 1998–1999, the sample was randomly selected from two sites, Greve in Chianti and Bagno a Ripoli, using a multistage stratified sampling method. Data collection included 1) a home interview concerning demographics, health-related behaviors, functional status, and cognitive function; 2) a medical examination including several performance-based tests of physical function conducted in the study clinic; and 3) 24-h urine collection and blood drawing. Participants were evaluated again at 3-yr (2001–2003) and 6-yr (2004–2006) follow-up visits. All respondents received an extensive description of the study and signed an informed consent. The study protocol complies with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging Ethical Committee.

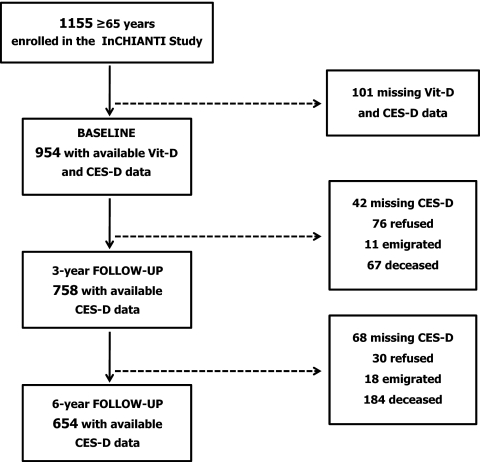

The study population selection is summarized in Fig. 1. Of the 1155 participants aged 65 yr or older enrolled in the study, 1055 (91.3%) donated a blood sample at enrollment. The subjects who did not participate in the blood drawing were generally older and had greater comorbidity than those who participated (22). We additionally excluded 101 participants because of missing data on Vit-D status or depressive symptoms. Among the remaining 954 participants, 758 had available data on depressive symptoms at 3-yr follow-up (42 had missing data, 76 refused to participate in the survey, 11 were emigrated, and 67 were deceased), and 654 had available data on depressive symptoms 6-yr follow-up (68 had missing data, 30 refused, 18 emigrated, and 184 deceased). Overall, 152 participants (15.9%) did not participate at both follow-up sessions. Those lost at both follow-ups, compared with participants who participated at least at one follow-up, were significantly older (80.5 vs. 73.2 yr), more often sedentary (38.2 vs. 14.7%), reported more disabilities in activities of daily living (0.4 vs. 0.1) and more comorbid chronic diseases (1.5 vs. 1.2), and had poorer cognitive function [Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores 23.4 vs. 25.9] and lower extremity performance [Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) scores 8.7 vs. 10.7].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study population selection.

Vit-D status

Vit-D status was measured at baseline by assessing circulating levels of 25(OH)D, which is the combined product of cutaneous synthesis from solar exposure and dietary sources. Morning fasting blood samples were collected after a 15-min rest. Aliquots of serum were stored at −80 C and never thawed before analysis. Serum 25(OH)D was measured by RIA (RIA kit; DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN). Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 8.1 and 10.2%, respectively. The assay consists of a two-step procedure (23). The first step involves a rapid extraction of 25(OH)D and other hydroxylated metabolites with acetonitrile; after extraction, the treated sample is then assayed using an equilibrium RIA procedure that uses a 25(OH)D-specific antibody. Although there is no formal consensus on the optimal levels of 25(OH)D, Vit-D insufficiency is often defined as a 25(OH)D level of less 50 nmol/liter (24). Only 25 participants (2.6%) of the sample, 22 women and two men, were taking vitamin supplements.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline and at the 3- and 6-yr follow-up visits using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (25). The CES-D is a 20-item self-report scale, ranging from 0–60. The CES-D has been shown to have good psychometric properties in assessing depressive symptoms in older adults (26), also in an Italian sample (27). A score of 16 or higher is generally considered to represent clinically relevant depressed mood (25).

Covariates

The following covariates assessed at baseline were selected: age, gender, education (years), smoking habit (current/former/nonsmoker), alcohol use (<30 vs. ≥30 g/d), MMSE score, body mass index (BMI), season of data collection (winter, spring, summer, and fall), number of prescribed and nonprescribed drugs, and use of antidepressants and vitamin D supplements coded according to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system. Level of physical activity in the previous 12 months was classified as sedentary/light/moderate-high (28). Number of activities of daily living (ADL) (0–6) and instrumental ADL (IADL) (0–8) disabilities was defined as self-report of inability or needing personal help in performing any basic ADL or IADL (29). Total number of chronic diseases (heart failure, coronary heart disease including angina and myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive lung disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, dementia, and hip arthritis) was calculated as a global marker of poor physical health; diseases were ascertained according to standardized, preestablished criteria and algorithms based upon those used in the Women’s Health and Aging Study (30) using information on self-reported history, pharmacological treatments, medical exam data, and hospital discharge records. The same method was used to ascertain osteoporosis. The SPPB (0–12; higher scores indicate better performance) was used to assess lower extremity function using a standard protocol as described elsewhere (31). Energy and Vit-D daily dietary intake were collected by the food-frequency questionnaire created for the European Prospective Investigation on Cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study, previously validated in the InCHIANTI population (32). Creatinine clearance was calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula adjusted for 1.73 body surface area calculated according to the DuBois and Dubois formula (33). Serum creatinine for this calculation was measured using a standard Jaffe method (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Serum intact PTH was measured with a two-site immunoradiometric assay kit (N-tact PTHSP; DiaSorin); intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 3.0 and 5.5%, respectively. PTH levels were dichotomized at the median (high vs. low; median = 22.2 pg/ml).

Statistical analyses

Variables were reported as percentage or means ± sd. All analyses were stratified by sex due to sex differences in 25(OH)D levels. Differences in baseline characteristics were tested according to 25(OH)D tertiles and 25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/liter vs. 50 nmol/liter or higher. Associations of 25(OH)D levels with changes in CES-D scores over time while accounting for correlation of repeated CES-D measures were analyzed by generalized estimating equations with an unstructured covariance (34). In all models, 25(OH)D status was coded as an indicator variable with higher level as the reference group. Appropriate 25(OH)D level-by-time interaction terms were included in the model to compare rates of change in CES-D scores between participants with different baseline serum 25(OH)D at each follow-up point. All models were adjusted for covariates that showed an association with 25(OH)D at baseline with a level of significance of P < 0.1 plus season of data collection. Next, Cox proportional hazards model was fit to compare risk of developing depressed mood over the follow-up period by Vit-D status. In these analyses, among the 954 participants available at enrollment, 298 subjects with prevalent depressed mood at baseline were excluded; in addition, 17 subjects who did not participate at both follow-up sessions and who did not die during the follow-up period were also excluded. Thus, the study sample for time-to-event analyses consisted of 639 subjects. Participants who survived without developing depressed mood were censored at the date of the last follow-up; those who died without developing depressed mood were censored at the time of their death. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to compare rates of depressed mood across 25(OH)D levels. Multivariable analyses were initially adjusted for age and baseline CES-D score and then additionally adjusted for the previously selected covariates that were significantly related to the outcome. The analyses were repeated in a subset of healthy participants with no ADL disabilities and with SPPB of 9 or higher at enrollment. Finally, an adjusted Cox proportional hazards model was fit including a baseline 25(OH)D level-by-sex interaction term to test whether associations were consistent across gender. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 8.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) with a statistical significance level set at P < 0.05.

Results

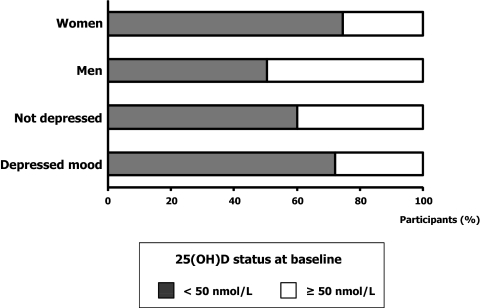

The study sample included 531 women (55.7%) and 423 men (44.3%) with average (±sd) age of 75.0 (±7.1) and 73.6 (±6.5) yr, respectively. Prevalence of depressed mood was 42% in women and 18.0% in men. As shown in Fig. 2, 74.6% of women and 50.4% of men had serum 25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/liter (P < 0.0001). Overall, 72.2% of participants with depressed mood and 60.0% of those without depressed mood at baseline had levels of 25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/liter (P = 0.0003). Table 1 describes the characteristics of participants for the total baseline sample and according to 25(OH)D tertiles (tertile 1, <31.7 nmol/liter; tertile 2, ≥31.7 to <53.9 nmol/liter; tertile 3, ≥53.9 nmol/liter). Participants with low levels of 25(OH)D were older, had a higher number of chronic diseases, were more likely to be disabled and sedentary, had lower SPPB scores, and were more likely to have participated in the data collection during winter. Men with low 25(OH)D also had low-energy dietary intake. Furthermore, women with low 25(OH)D were more likely to take antidepressants, had lower BMI, and tended to have higher PTH, lower MMSE scores, and fewer years of education. At baseline, men and women in the higher 25(OH)D tertiles tended to have fewer depressive symptoms than those in the higher tertiles, although differences across tertiles were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Serum 25(OH)D status at baseline in men and women and in participants with and without depressed mood. Depressed mood is based on CES-D score of 16 or higher.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at baseline

| Characteristics | Total sample (n = 954) | 25(OH)D

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men

|

Women

|

|||||||||

| Tertile 1 (n = 84) | Tertile 2 (n = 136) | Tertile 3 (n = 203) | P* | Tertile 1 (n = 232) | Tertile 2 (n = 184) | Tertile 3 (n = 115) | P | |||

| Age (yr) | 74.4 ± 6.9 | 77.1 ± 7.4 | 73.9 ± 6.0 | 72.0 ± 5.9 | <0.0001 | 77.2 ± 7.5 | 74.1 ± 6.6 | 72.0 ± 5.7 | <0.0001 | |

| Education (yr) | 5.5 ± 3.3 | 5.8 ± 3.7 | 6.2 ± 3.7 | 6.6 ± 3.5 | 0.79 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 5.5 ± 2.8 | 0.08 | |

| Alcohol use (≥3 drinks/d) (%) | 15.2 | 21.4 | 30.9 | 36.5 | 0.68 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 0.59 | |

| Smoking status (%) | 0.77 | 0.87 | ||||||||

| Nonsmoker | 58.7 | 32.1 | 25.0 | 30.5 | 84.1 | 83.2 | 77.4 | |||

| Former smoker | 26.9 | 50.0 | 52.9 | 46.8 | 6.9 | 9.8 | 12.2 | |||

| Current smoker | 14.4 | 17.9 | 22.1 | 22.7 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 10.4 | |||

| MMSE scores | 25.3 ± 3.2 | 25.1 ± 3.2 | 25.9 ± 2.7 | 26.1 ± 2.8 | 0.86 | 24.1 ± 3.8 | 24.9 ± 3.1 | 25.9 ± 3.0 | 0.10 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 4.1 | 27.2 ± 3.4 | 26.9 ± 3.2 | 27.1 ± 3.3 | 0.54 | 27.8 ± 4.8 | 28.5 ± 4.8 | 27.2 ± 3.8 | 0.03 | |

| Physical activity (%) | <0.0001 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Low | 18.6 | 27.4 | 14.0 | 3.5 | 32.8 | 22.8 | 8.7 | |||

| Medium | 75.7 | 69.1 | 76.5 | 85.7 | 65.5 | 74.5 | 84.4 | |||

| High | 5.8 | 3.6 | 9.6 | 10.8 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 7.0 | |||

| CES-D score | 12.7 ± 8.8 | 11.3 ± 9.2 | 9.2 ± 6.6 | 9.1 ± 6.6 | 0.5 | 15.4 ± 8.9 | 15.5 ± 9.6 | 14.4 ± 8.9 | 0.74 | |

| No. of ADL disabilities | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.04 ± 0.4 | 0:03 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.04 ± 0.3 | 0.01 ± 0.1 | 0.02 | |

| No. of IADL disabilities | 0.6 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 0.4 ± 1.3 | 0.2 ± 0.9 | 0.005 | 1.2 ± 2.1 | 0.4 ± 1.2 | 0.01 ± 0.1 | 0.007 | |

| No. of drugs | 2.2 ± 2.0 | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 2.0 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 2.0 | 0.5 | 2.6 ± 2.1 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 0.65 | |

| Antidepressants use (%) | 4.4 | 6.0 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 0.59 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 1.7 | 0.03 | |

| Vitamin D supplementation (%) | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.38 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 0.25 | |

| No. of chronic diseases | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 0.045 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 0.027 | |

| Osteoporosis (%) | 19.6 | 11.9 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 0.46 | 30.2 | 19.0 | 23.5 | 0.36 | |

| SPPB score | 10.1 ± 2.8 | 9.4 ± 3.3 | 10.8 ± 2.3 | 11.2 ± 1.8 | 0.002 | 8.8 ± 3.5 | 10.2 ± 3.3 | 10.5 ± 2.1 | 0.007 | |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 1929.4 ± 561.6 | 1941.2 ± 526.9 | 2214.7 ± 533.7 | 2262.7 ± 537.1 | 0.006 | 1718.0 ± 451.1 | 1703.7 ± 472.7 | 1778.4 ± 543.9 | 0.51 | |

| Vitamin D intake (μg/d) | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 2.8 | 0.54 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 0.48 | |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/min) | 65.5 ± 18.9 | 64.1 ± 19.1 | 69.6 ± 17.8 | 73.2 ± 17.6 | 0.93 | 58.2 ± 17.9 | 62.8 ± 19.6 | 66.1 ± 17.5 | 0.9 | |

| High PTH (%) | 50.2 | 60.9 | 31.3 | 0.5 | 60.9 | 31.3 | 0.08 | |||

| Season of data collection (%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Winter | 34.6 | 60.8 | 46.9 | 25.7 | 47.7 | 30.6 | 16.3 | |||

| Spring | 16.1 | 9.8 | 18.5 | 14.3 | 12.6 | 25.3 | 5.9 | |||

| Summer | 12.6 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 18.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 28.9 | |||

| Fall | 36.7 | 25.5 | 30.9 | 41.4 | 31.1 | 35.5 | 48.9 | |||

Results are shown as mean ± sd unless indicated as percent. Tertiles for 25(OH)D are as follows: tertile 1 <31.7 nmol/liter; tertile 2, 31.7 to less than 53.9 nmol/liter; and tertile 3, 53.9 nmol/liter or higher. High PTH is over 22.2 pg/ml. P values are based on age-adjusted general linear model or logistic regression as appropriate.

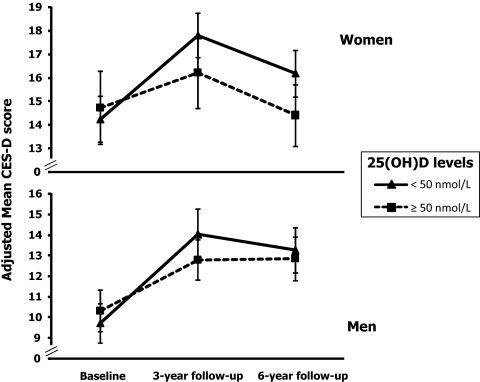

Generalized estimating equation models adjusted for age, education, MMSE score, physical activity, ADL and IADL disabilities, BMI, use of antidepressants, number of chronic diseases, SPPB score, energy intake, high PTH, and season of data collection were fit to compare average changes in depressive symptoms over time across baseline 25(OH)D levels (Table 2). Women in tertiles 1 and 2, compared with those in the highest tertile, experienced increases in CES-D scores of, respectively, 2.2 (se = 1.0; P = 0.03) and 1.1 (se = 1.0; P = 0.26) points higher after 3 yr, and 2.5 (se = 1.3; P = 0.05) and 1.7 (se = 1.2; P = 0.16) points higher after 6 yr. Similarly, men in tertiles 1 and 2, compared with those in the highest tertile, experienced increases in CES-D scores of 2.1 (se = 1.2; P = 0.06) and 1.9 (se = 0.9; P = 0.03) points higher after 3 yr and 0.7 (se = 1.5; P = 0.63) and 1.3 (se = 0.8; P = 0.12) points higher after 6 yr. Analogous results were obtained when 25(OH)D was dichotomized using a cutoff threshold of 50 nmol/liter (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Among women, the 3- and 6-yr average adjusted increases in CES-D scores were, respectively 2.1 (se = 0.9; P = 0.02) and 2.2 (se = 1.1; P = 0.04) points higher for women with 25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/liter compared with those with levels of 50 nmol/liter or higher. Among men, the 3- and 6-yr average increases were, respectively, 1.9 (se = 0.8; P = 0.01) and 1.1 (se = 0.8; P = 0.20) points higher for those with 25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/liter compared with those with levels of 50 nmol/liter or higher, although the differential change in CES-D score according to 25(OH)D level was statistically significant only at 3-yr follow-up.

Table 2.

Adjusted associations between 25(OH)D levels and CES-D scores

| 25(OH)D | Men

|

Women

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline

|

Follow-up 1

|

Follow-up 2

|

Baseline

|

Follow-up 1

|

Follow-up 2

|

|||||||

| β (se) | P | β (se) | P | β (se) | P | β (se) | P | β (se) | P* | β (se) | P | |

| Tertile 3 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Tertile 2 | –1.02 (0.7) | 0.14 | 1.91 (0.9) | 0.03 | 1.32 (0.8) | 0.12 | 0.65 (1.1) | 0.55 | 1.13 (1.0) | 0.26 | 1.73 (1.2) | 0.16 |

| Tertile 1 | 0.04 (1.0) | 0.97 | 2.13 (1.2) | 0.06 | 0.74 (1.5) | 0.63 | −0.53 (1.1) | 0.63 | 2.20 (1.0) | 0.03 | 2.50 (1.3) | 0.05 |

| ≥50 nmol/liter | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| <50 nmol/liter | –0.64 (0.7) | 0.35 | 1.91 (0.8) | 0.01 | 1.07 (0.8) | 0.20 | 0.001 (1.0) | 0.9 | 2.05 (0.9) | 0.02 | 2.19 (1.1) | 0.04 |

All analyses were adjusted for age, education, MMSE score, physical activity, BMI, ADL and IADL disabilities, use of antidepressants, number of chronic diseases, SPPB score, energy intake, high PTH, and season of data collection. Tertiles for 25(OH)D are as follows: tertile 1 <31.7 nmol/liter; tertile 2, 31.7 to less than 53.9 nmol/liter; and tertile 3, 53.9 nmol/liter or higher. Ref, Reference.

Figure 3.

CES-D scores during 6 yr of follow-up according to baseline 25(OH)D levels in women and men. Estimated means and 95% CI are adjusted for age, education, MMSE score, physical activity, BMI, ADL and IADL disabilities, use of antidepressants, number of chronic diseases, SPPB score, energy intake, high PTH, and season of data collection.

Lower baseline serum levels of 25(OH)D were also associated with higher probability of developing depressed mood during the follow-up (Table 3). Of the 298 women and 342 men who were free of the depressed mood at baseline, 130 women (43.6%) and 70 men (20.5%) developed depressed mood. After adjustment for age, baseline CES-D, ADL disabilities, use of antidepressants, number of chronic diseases, SPPB, high PTH, and season of data collection, women in the lowest tertile of 25(OH)D had a higher hazard (HR = 2.6; 95% CI = 1.4–4.6; P = 0.002) of developing depressed mood during 6 yr of follow-up compared with those in the highest tertile. Similarly, men in the lowest tertile, compared with those in the highest tertile, had a higher hazard (HR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.0–4.0; P = 0.07) of developing depressed mood, although the association was not statistically significant. Analogous results were obtained using the cutoff of 50 nmol/liter; HR for new depression for women and men with lower level of 25(OH)D, compared with those with higher levels, were, respectively, 2.0 (95% CI = 1.2–3.2; P = 0.005) and 1.6 (95% CI = 0.9–2.8; P = 0.1). To obtain a picture of the effect of Vit-D status free of the possible confounding effect of disability or poor physical functioning, we performed additional analyses restricted to a subset of 535 healthy participants with no ADL disabilities and SPPB of 9 or higher at baseline. Again, we found that women (HR = 2.1; 95% CI = 1.3–3.5; P = 0.005) and men (HR = 1.5; 95% CI = 0.8–2.7; P = 0.2) with low levels of 25(OH)D had higher risk of developing depressed mood compared with those with higher levels (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted risk of depressed mood according to baseline 25(OH)D levels

| 25(OH)D | Men

|

Women

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a

|

Model 2b

|

Model 1a

|

Model 2b

|

|||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| n = 639 | ||||||||||||

| Tertile 3 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Tertile 2 | 1.05 | 0.60–1.85 | 0.87 | 1.03 | 0.55–1.90 | 0.93 | 1.57 | 0.92–2.66 | 0.097 | 1.72 | 0.98–3.00 | 0.06 |

| Tertile 1 | 1.74 | 0.95–3.18 | 0.07 | 1.96 | 0.96–4.00 | 0.07 | 2.15 | 1.30–3.57 | 0.003 | 2.56 | 1.41–4.64 | 0.002 |

| ≥50 nmol/liter | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| <50 nmol/liter | 1.62 | 0.99–2.64 | 0.05 | 1.61 | 0.92–2.82 | 0.10 | 1.87 | 1.22–3.57 | 0.004 | 1.97 | 1.22–3.17 | 0.005 |

| n = 535 participants with no ADL disabilities and SPPB ≥9 at baseline | ||||||||||||

| Tertile 3 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Tertile 2 | 0.96 | 0.53–1.75 | 0.9 | 0.97 | 0.51–1.83 | 0.92 | 1.66 | 0.93–2.97 | 0.09 | 1.75 | 0.96–3.20 | 0.07 |

| Tertile 1 | 1.6 | 0.81–3.16 | 0.17 | 1.67 | 0.76–3.68 | 0.21 | 2.36 | 1.36–4.12 | 0.002 | 2.90 | 1.53–5.50 | 0.001 |

| ≥50 nmol/liter | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| <50 nmol/liter | 1.47 | 0.87–2.48 | 0.15 | 1.46 | 0.81–2.65 | 0.21 | 2.01 | 1.26–3.21 | 0.004 | 2.09 | 1.25–3.49 | 0.005 |

Depressed mood is based on CES-D of 16 or higher. Tertiles for 25(OH)D are as follows: tertile 1 <31.7 nmol/liter; tertile 2, 31.7 to less than 53.9 nmol/liter; and tertile 3, 53.9 nmol/liter or higher. Ref, Reference.

Adjusted for age and baseline CES-D.

Adjusted for age, baseline CES-D, ADL disabilities, use of antidepressants, number of chronic diseases, SPPB, high PTH and season of data collection.

To better interpret the difference in the strength of the association between 25(OH)D level and depression in women and men, we included a 25(OH)D status-by-sex interaction term in a fully adjusted Cox regression model predicting depression in the whole study sample. The interaction term was not statistically significant, suggesting that the nature of association between 25(OH)D and depression is substantially similar in the two sexes.

Discussion

Using data from a population-based study of older persons, we found evidence of a prospective independent association between circulating levels of 25(OH)D and depressive symptoms. Participants with low 25(OH)D serum levels experienced a grater increase in depressive symptoms over 6 yr of follow-up. Moreover, among participants free of clinically relevant depressive symptoms at baseline, a higher risk of developing clinically relevant depressive symptoms over time was found for those with low serum 25(OH)D. In the baseline sex-stratified analysis, men and women with higher 25(OH)D levels tended to have lower depressive symptoms, although the difference was statistically significant only in analyses that included both men and women.

It has been hypothesized (14) the association between Vit-D and depression may be difficult to capture in cross-sectional analyses because clinically detectable mood disorders may take many years to develop.

Relatively few cross-sectional epidemiological studies have evaluated the relationship between Vit-D and depression in older adults, and results have been mixed. In one study (16) comparing 40 individuals with mild Alzheimer’s disease with 40 nondemented persons, all over 60 yr of age, subjects with low 25(OH)D were significantly more likely to have a mood disorder, although the mean depressive features score did not vary by Vit-D status. In the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (20), depression symptoms as measured by CES-D scores was significantly associated with 25(OH)D. Moreover, mean 25(OH)D levels in participants with major depressive disorder and those with minor depression were comparable and 14% lower than those of nondepressed participants. More recently, a large cross-sectional study (19) of older adults in China found no associations between 25(OH)D levels and depressive symptoms as assessed by CES-D.

Different mechanisms through which Vit-D may potentially influence brain functions have been proposed (10,11,12). First of all, Vit-D may have a direct neuroregulatory activity. Vit-D receptors (VDR) and 25(OH)D3 1α-hydroxylase, the cytochrome P450 that catalyzes the hydroxylation of calcidiol to calcitriol (the bioactive form of Vit-D), are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system (35). VDR gene polymorphisms in humans have been associated with cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms (36). Furthermore, Vit-D regulates the expression of important neurotrophic factors that affect neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity (11). Moreover, Vit-D has been shown to be neuroprotective, notably by inducing the synthesis of calcium-binding proteins or by antioxidant mechanisms (10,11,12). Finally, the immunomodulatory activity of Vit-D has been related to recent evidence that inflammation may play a causal role in depression: Vit-D has been shown to down-regulate inflammatory mediators, such as nuclear factor κB, which have been linked to sickness behavior, psychosocial stress, and depression (11,37).

Sex differences in the relationship between 25(OH)D and depression could be attributable to different factors. One explanation for the weaker association between 25(OH)D and depression in men could be the smaller number of men with low levels of 25(OH)D. Furthermore, in our study sample, women were older, and those with lower 25(OH)D showed specific characteristics (use of antidepressants, low BMI, MMSE, years of education, and high PTH) commonly associated with depression (12,19).

Our study has both strengths and limitations. A major strength of this study is the use of a large population-based sample with measured serum 25(OH)D, which is the best clinical indicator of Vit-D body store levels, and the longitudinal design. An important limitation of our study is the loss of participants to follow-up. Participants lost to follow-up were significantly older and more disabled and had poorer cognitive function and more chronic diseases compared with those available for longitudinal analysis; this could limit the generalization of the findings. Another limitation of this study is that depressive symptoms were evaluated by the CES-D questionnaire, and the diagnosis of depression was not confirmed by a clinical psychiatric diagnosis. However, the CES-D is a commonly used scale to measure depressive symptoms, has been widely used in older population-based studies, and has been shown to substantially converge with physician ratings of depression (26). In addition, because of the long intervals between follow-up visits, we could not detect depressive episodes that started and remitted between subsequent visits. Finally, residual confounding in studies of Vit-D and depression should be considered. A variety of factors are associated with Vit-D, including age, physical activity, disability, and chronic diseases such as osteoporosis, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, autoimmune, and infectious diseases (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). Many of these factors are also associated with depression in older age (12). In the present study, lower levels of 25(OH)D were associated with more disabilities and comorbidities and could have resulted in more incident unfavorable health events, which in turn could have increased depressive symptoms; even though our analysis was adjusted for an extensive array of potential confounders, we cannot exclude the hypothesis that some critical variable was not measured. In other terms, we cannot exclude that the association between Vit-D and depressive symptoms in this study could be still partially explained by residual confounding. However, the association between 25(OH)D and depressed mood remained significant after the selection of a subset of healthy participants with no disabilities and high physical function as measured by SPPB, a strong predictor of nursing home admission, disability in self-care tasks and mobility, and death among older adults (31).

Despite limitations, we believe that our findings provide evidence of a prospective association between low Vit-D levels and the onset of depressive symptoms in older persons over time. Such evidence is not sufficient to conclude with certainty that there is a causal connection. However, our findings in conjunction with recent preclinical studies that confirmed the strong biological activity of Vit-D on brain function (11,12,16) suggests the hypothesis that normalization of Vit-D levels may positively contribute to the successful treatment of depression in older persons.

Hypovitaminosis D is highly prevalent throughout the world in the elderly (1). Potentially modifiable determinants of Vit-D status, such as consumption of Vit-D-rich food, fortification of foods, use of dietary supplements, and habits related to sun exposure, have been identified (9,38). Prevention of Vit-D deficiency in the elderly may become in the future a strategy to prevent the development of depressive mood in the elderly (39) and avoid its deleterious consequences on health (12). In addition, normalization of Vit-D levels may be part of any depression treatment plans in older patients. These hypotheses should be tested in appropriately designed, randomized, controlled trials.

Footnotes

The InCHIANTI study baseline (1998–2000) was supported as a targeted project (ICS110.1/RF97.71) by the Italian Ministry of Health and in part by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts 263 MD 9164 and 263 MD 821336); the InCHIANTI Follow-Up 1 (2001–2003) was funded by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts N.1-AG-1-1 and N.1-AG-1-2111); the InCHIANTI Follow-Ups 2 and 3 studies (2004–2010) were financed by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contract N01-AG-5-0002); this study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 5, 2010

Abbreviations: ADL, Activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IADL, instrumental ADL; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; Vit-D, vitamin D.

References

- van der Wielen RP, Löwik MR, van den Berg H, de Groot LC, Haller J, Moreiras O, van Staveren WA 1995 Serum vitamin D concentrations among elderly people in Europe. Lancet 346:207–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, Giovannucci E, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B 2005 Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 293:2257–2264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston DK, Cesari M, Ferrucci L, Cherubini A, Maggio D, Bartali B, Johnson MA, Schwartz GG, Kritchevsky SB 2007 Association between vitamin D status and physical performance: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62:440–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shardell M, Hicks GE, Miller RR, Kritchevsky S, Andersen D, Bandinelli S, Cherubini A, Ferrucci L 2009 Association of low vitamin D levels with the frailty syndrome in men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64:69–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P; Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam 2003 Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:5766–5772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks GE, Shardell M, Miller RR, Bandinelli S, Guralnik J, Cherubini A, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L 2008 Associations between vitamin D status and pain in older adults: the Invecchiare in Chianti study. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:785–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Deeg DJ, Puts MT, Seidell JC, Lips P 2006 Low serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in older persons and the risk of nursing home admission. Am J Clin Nutr 84:616–622; quiz 671–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autier P, Gandini S 2007 Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 167:1730–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF 2004 Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 80(Suppl):1678S–88S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes de Abreu DA, Eyles D, Féron F 2009 Vitamin D, a neuro-immunomodulator: Implications for neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34(Suppl 1):S265–S277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann JC, Ames BN 2008 Is there convincing biological or behavioral evidence linking vitamin D deficiency to brain dysfunction? FASEB J 22:982–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS 2005 Depression in the elderly. Lancet 365:1961–1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniak EP, Florez H, Roos BA, Troen BR, Levis S 2008 Hypovitaminosis D in the elderly: from bone to brain. J Nutr Health Aging 12:366–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniack EP, Troen BR, Florez HJ, Roos BA, Levis S 2009 Some new food for thought: the role of vitamin D in the mental health of older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep 11:12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertone-Johnson ER 2009 Vitamin D and the occurrence of depression: causal association or circumstantial evidence? Nutr Rev 67:481–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM, Birge SJ, Morris JC 2006 Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14:1032–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DJ, Meenagh GK, Bickle I, Lee AS, Curran ES, Finch MB 2007 Vitamin D deficiency is associated with anxiety and depression in fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol 26:551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorde R, Sneve M, Figenschau Y, Svartberg J, Waterloo K 2008 Effects of vitamin D supplementation on symptoms of depression in overweight and obese subjects: randomized double blind trial. J Intern Med 264:599–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan A, Lu L, Franco OH, Yu Z, Li H, Lin X 2009 Association between depressive symptoms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J Affect Disord 118:240–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendijk WJ, Lips P, Dik MG, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, Penninx BW 2008 Depression is associated with decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D and increased parathyroid hormone levels in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65:508–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, Di Iorio A, Macchi C, Harris TB, Guralnik JM 2000 Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc 48:1618–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrager MA, Metter EJ, Simonsick E, Ble A, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Ferrucci L 2007 Sarcopenic obesity and inflammation in the InCHIANTI study. J Appl Physiol 102:919–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis BW, Kamerud JQ, Selvaag SR, Lorenz JD, Napoli JL 1993 Determination of vitamin D status by radioimmunoassay with an 125I-labeled tracer. Clin Chem 39:529–533 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips P 2001 Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev 22:477–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS 1977 The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure 1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W 1997 Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med 27:231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA 1983 Assessing depressive symptoms across cultures: Italian validation of the CES-D self-rating scale. J Clin Psychol 39:249–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs Jr DR, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, Paffenbarger Jr RS 1993 Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 25:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendal FP, McCreary EK 1983 Muscle testing and function. Baltimore: Williams, Wilkins [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Kasper D, Lafferty ME 1995 The Women’s Health and Aging Study: health and social characteristics of older women with disability. NIH Pub. No. 95-4009. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB 1994 A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 49:M85–M94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani P, Faggiano F, Krogh V, Palli D, Vineis P, Berrino F 1997 Relative validity and reproducibility of a food frequency dietary questionnaire for use in the Italian EPIC centres. Int J Epidemiol 26(Suppl 1):S152–S160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzarelli F, Lauretani F, Bandinelli S, Windham GB, Corsi AM, Giannelli SV, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM 2009 Predictivity of survival according to different equations for estimating renal function in community-dwelling elderly subjects. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24:1197–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twisk JW 2004 Longitudinal data analysis. A comparison between generalized estimating equations and random coefficient analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 19:769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, Hewison M, McGrath JJ 2005 Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1α-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat 29:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuningas M, Mooijaart SP, Jolles J, Slagboom PE, Westendorp RG, van Heemst D 2009 VDR gene variants associate with cognitive function and depressive symptoms in old age. Neurobiol Aging 30:466–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL 2009 Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 65:732–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam RM, Snijder MB, Dekker JM, Stehouwer CD, Bouter LM, Heine RJ, Lips P 2007 Potentially modifiable determinants of vitamin D status in an older population in The Netherlands: the Hoorn Study. Am J Clin Nutr 85:755–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SN 2009 Has the time come for clinical trials on the antidepressant effect of vitamin D? J Psychiatry Neurosci 34:3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]