Abstract

Context: Real-world adherence to bisphosphonate therapy is poor. Consistent data support a relation between medication adherence and fracture reduction, but relatively little attention has been paid to the effect of the method used to measure adherence on this relation or on the relation between adherence and specific fracture types.

Objective: Our objective was to assess the relation between bisphosphonate adherence and the risk of hip, vertebral, distal forearm, and any fracture using different measures of adherence.

Design: We conducted a cohort study using administrative claims data. Adherence was assessed in sequential 60-d periods. In models incorporating time-varying measures of adherence, the adjusted relation between adherence and fracture was examined using several methods for calculating the proportion of days covered (PDC).

Patients: Patients included community-dwelling elderly enrolled in a Pennsylvania pharmaceutical assistance program and Medicare initiating an oral bisphosphonate for osteoporosis.

Main Outcome Measures: Risk of hip, vertebral, distal forearm, and any osteoporotic fracture was assessed.

Results: Fractures occurred at a rate of 43 per 1000 person-years among the 19,987 patients meeting study eligibility criteria. There was an inverse relation between adherence and fracture rate for all adherence measures and fracture types, excluding distal forearm fractures. High (80–100%) cumulative PDC was associated with a 22% reduction in overall fracture rate, a 23% reduction in hip fracture rate, and 26% reduction in vertebral fracture rate.

Conclusions: We found a consistent relation between adherence with osteoporosis treatment and fracture reduction, regardless of method for measuring PDC. The similarity in results across adherence measures is likely due to the high correlation between them.

The relation between bisphosphonate adherence and fracture risk varies by anatomic site but is consistent across adherence measures.

Osteoporotic fractures are common and costly. It has been estimated that more than 2 million fractures occur each year, resulting in direct medical costs of $19 billion (1). Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of bisphosphonate therapy to reduce vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in patients with osteoporosis, with estimated risk reduction of 40–50 and 20–40%, respectively (2). These risk reductions assume the high adherence rates observed in clinical trials. In contrast, real-world adherence to bisphosphonate therapy is poor, with approximately 50% of subjects discontinuing therapy within 1–2 yr (3). Understanding the effect of suboptimal adherence on bisphosphonate effectiveness is crucial for projecting the effect of screening and treatment strategies in terms of fracture reductions (4,5).

Although a number of studies have evaluated the association between bisphosphonate adherence and fracture risk in medical claims databases (6), data regarding the fracture risk reduction obtained at specific adherence levels are limited, especially for individual anatomic sites. Results from a recent paper, which compared fracture rates after nonadherent periods during which patients had less than 50% of days with medication supply available to adherent periods with at least 80% suggest that the effect of nonadherence may vary by fracture type (7). However, the reported data provide no information regarding fracture rates for adherence between 50 and 80%, and the use of the broad under 50% adherence category to define nonadherence may mask difference between 0 and 50% adherence. Furthermore, relatively little attention has been paid to the way in which adherence is measured. This same study evaluated two different approaches to measuring adherence, comparing a time-varying approach where adherence was measured at the beginning of every 90-d interval to a non-time-varying approach where adherence was measured at the end of 2.5 yr, and found that the estimated adherence-effectiveness relation varied considerably by approach. Assuming the time-varying approach is preferable, as the study argues convincingly, questions remain regarding the best method for calculating adherence over time.

In this paper, we present data on the relation between bisphosphonate adherence and hip, vertebral, distal forearm, and overall fracture rates. We used several different adherence measures, ranging from measurement of adherence in the past 60 d only (instantaneous adherence) to a measure of adherence since treatment initiation (cumulative adherence), to explore the impact of adherence definition on estimated associations. These different measures of adherence may capture different biological aspects of the relation between medications and fracture reduction, specifically difference between short-term and long-term effects.

Patients and Methods

Study cohort

The study cohort was drawn from a patient population aged 65 yr or older dually enrolled in Medicare and the Pennsylvania Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly (PACE) program between 1996 and 2005. PACE, a state-run pharmaceutical benefit program for households with incomes less than $17,200, provides coverage for all prescription drugs with a copayment of between $6 and $9. Our cohort consisted of PACE/Medicare enrollees who initiated a bisphosphonate between 1996 and 2005. Initiation was defined as filling a bisphosphonate prescription without having filled one in the past 365 d. To ensure accurate ascertainment of drug and healthcare system use during this 365-d baseline period, we required that subjects were enrolled in PACE and Medicare during the entire period. We excluded subjects with evidence of Paget’s disease of the bone, malignant neoplasms, HIV, or use of nasal calcitonin, raloxifene, or teriparatide during the baseline period. Nursing home residents’ medication use is not consistently reported, and thus, they were also excluded.

Baseline characteristics

We ascertained baseline subject characteristics from several sources: enrollment files, PACE prescription drug claims, and Medicare Part A and B claims during the 365 d before the index date. Characteristics collected include demographic characteristics (age, race, and gender), general measures of comorbidity and health system use [number of hospitalizations, number of physician visits, number of different drugs prescribed (8), and Romano comorbidity score (9)], and risk factors for falls and low bone mineral density (history of falls, syncope, diabetes mellitus, stroke or TIA, gait abnormalities, hyperparathyroidism, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s or other dementia, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), renal disease, kyphosis, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and depression; and prior use of hormone replacement therapy, gastroprotective agents, glucocorticoids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants, β-blockers, thiazide diuretics, and benzodiazepines). Because preventive health service use has been shown to be correlated with medication adherence (10), we also measured baseline receipt of recommended screening tests (bone mineral density, cervical cancer screening, fecal occult blood, and screening mammography) and immunizations (influenza and pneumonia).

Outcomes and study design

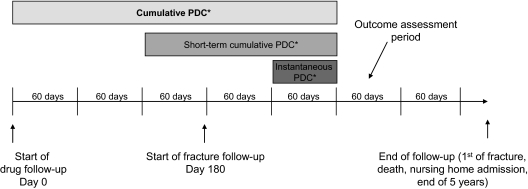

Follow-up began 180 d after the index date and ended at the first of any of the following events: fracture, loss of PACE eligibility, nursing home admission, death, the end of 5 yr, or the end of available data. We chose 5 yr because in an elderly population with high rates of mortality and nursing home admission, the population remaining after 5 yr is likely to be small and not representative of the initial population of bisphosphonate initiators. Follow-up time was divided into a series of 60-d intervals. The outcome of interest was fracture in the current (outcome assessment) interval, and the exposure of interest was adherence during the preceding interval or intervals, depending on the definition of adherence (Fig. 1). The first 180 d after the index date were excluded from the analysis on the grounds that no clinical benefit should be observed this early in therapy (11). Subjects experiencing a fracture during this period were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

Study design. Subjects’ adherence was measured in 60-d periods. Each subject contributed from one to 27 60-d periods to the study follow-up time. The three methods of measuring adherence are described in the figure as cumulative PDC (over entire period from drug initiation to outcome assessment period), short-term cumulative PDC (over 180 d before outcome assessment period), and instantaneous PDC (over 60 d before outcome assessment period) The outcome assessment period represented in the figure is for illustrative purposes only. All 60-d periods starting 180 d after bisphosphonate initiation were included as outcome assessment periods. *, PDC was calculated as days of bisphosphonate therapy available divided by days of cohort membership.

Fractures were defined based on diagnosis and procedure codes easily identified in the study database. These codes have been combined in algorithms that accurately define many fracture types, including hip, pelvis, humerus, and forearm (12,13). We also included other fracture types with algorithms previously defined in the literature. The exact algorithms are given in Supplemental Appendix I (published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). The primary outcome for these analyses was a composite of all fracture types (hip, nonhip femur, humerus, tibia/fibula, proximal forearm, distal forearm, clavicle/scapula, sternum, spine, and pelvis). In addition, we evaluated hip, vertebral, and distal forearm fractures individually. Although the outcome definitions employed do not specifically exclude open fractures, which are unlikely to be due to osteoporosis, 98% of hip and distal forearm fractures observed in this population are closed fractures. Pathological fractures were included, but patients with malignancy at baseline were excluded from the study cohort (14,15).

Medication adherence

Medication adherence was calculated for a series of 60-d intervals. Adherence was measured using the proportion of days covered (PDC), which was computed as the number of days for which the patient has bisphosphonate prescription supply available in an interval divided by the number of days of follow-up time the patient contributed to that interval. This measure of adherence has been widely used in previous studies, and our definition conforms with recommendations (16). Time spent in hospital was subtracted from the denominator on the assumption that the patient would not use his or her pill supply during a hospitalization.

We considered three different adherence measures in analyses, depicted in Fig. 1. Cumulative adherence was defined as the average adherence over all 60-d intervals preceding the outcome assessment interval. Thus, the denominator would be time since initiation. Short-term cumulative adherence was based on the three intervals immediately before the outcome assessment interval, with the denominator fixed at 180 d minus any time spent in hospital. Instantaneous adherence was based on only the one most proximal interval; thus, the denominator was 60 d minus any time spent in hospital. Because instantaneous adherence is likely to be correlated with cumulative adherence, we conducted an additional analysis of the effect of instantaneous adherence adjusted for past cumulative adherence to assess the independent effect of recent adherence.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a conditional logistic regression model in SAS version 9.2. In these analyses, adherence was categorized into 20% bands of PDC (0–19%, 20–39%, etc.), with the 0–19% category serving as the referent group. Because the number of patients contributing to the middle PDC categories was fairly small, we also fit isotonic regression models in the software package R (17). The isotonic regression procedure fits a curve using exact observed PDC values under the constraint that the fracture risk can only increase or remain the same with decreasing PDC (18). This leverages the assumption of a monotone relation between PDC and fracture risk (effectively, procedure borrows information from adjacent PDC categories) to provide more precise estimates of likely fracture risk in the middle PDC categories where data are sparse. We used the isotonic regression procedure because it is unlikely that increasing PDC could be related to increased fracture risk. We report both adjusted hazard ratios and isotonic regression results because the statistical package R doesn’t support covariate adjustment in isotonic regression.

The study investigators have data use agreements in place with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and PACE. This research was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 37,010 subjects who initiated a bisphosphonate between 1996 and 2005. After excluding 5131 with previous use of an osteoporosis medication; 5761 with Paget’s disease, cancer, or HIV; 2539 with nursing home residency; 713 who experienced a fracture during the 180 d immediately after the index date; and 2879 who were censored during the 180 d after the index date, we were left with a population of 19,987. These patients were predominantly white (96%) and female (97%) and had a median age of 79 yr. Based on diagnoses recorded during the year before bisphosphonate initiation, 5.5% of patients had experienced a previous fracture, 8.1% had a history of falls, 5.1% had gait abnormalities, and 6.4% had a syncope diagnosis. Gastroprotective agents were used by 32%, oral corticosteroids by 13%, benzodiazepines by 16.0%, and thiazide diuretics by 14.5%. As shown in Table 1, patients with lower cumulative PDC at 180 d were slightly older, more likely to have been hospitalized, and more likely to have asthma, COPD, or depression. These patients used more medications and had higher rates of benzodiazepine and gastroprotective agent use but were less likely to have received a bone mineral density test or influenza vaccination. However, the observed differences were small.

Table 1.

Baseline covariates by cumulative proportion of days covered at 180 d

| Cumulative PDC

|

P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–19% | 20–39% | 40–59% | 60–79% | 80–100% | ||

| n | 7193 | 564 | 1437 | 1227 | 9566 | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean (sd) | 79.1 (6.4) | 78.5 (6.3) | 78.8 (6.4) | 78.5 (6.3) | 78.9 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 246 (3.4) | 12 (2.1) | 51 (3.6) | 22 (1.8) | 268 (2.8) | 0.005 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 6876 (95.6) | 539 (95.6) | 1355 (94.3) | 1172 (95.5) | 9254 (96.7) | |

| Black | 233 (3.2) | 22 (3.9) | 63 (4.4) | 42 (3.4) | 191 (2) | <0.001 |

| Other | 84 (1.2) | 3 (0.5) | 19 (1.3) | 13 (1.1) | 121 (1.3) | 0.573 |

| General clinical status and service use | ||||||

| Romano score, mean (sd) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.3) | 0.006 |

| Number physician visits, mean (sd) | 9.3 (6.4) | 9.3 (6.9) | 9.2 (6.3) | 9.0 (6.3) | 8.8 (5.9) | <0.0001 |

| Number generics used, mean (sd) | 8.7 (5.3) | 9.0 (5.5) | 8.5 (5.3) | 8.2 (5.2) | 8.1 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hospitalization | 1779 (24.7) | 126 (22.3) | 314 (21.9) | 264 (21.5) | 2070 (21.6) | <0.0001 |

| Bone mineral density test | 2472 (34.4) | 213 (37.8) | 567 (39.5) | 536 (43.7) | 4307 (45) | <0.001 |

| Influenza vaccination | 3918 (54.5) | 300 (53.2) | 819 (57) | 708 (57.7) | 5740 (60) | <0.001 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||

| Fracture | 396 (5.5) | 41 (7.3) | 65 (4.5) | 57 (4.6) | 535 (5.6) | 0.094 |

| Falls | 599 (8.3) | 55 (9.8) | 114 (7.9) | 90 (7.3) | 767 (8) | 0.458 |

| Gait abnormalities | 390 (5.4) | 27 (4.8) | 53 (3.7) | 58 (4.7) | 494 (5.2) | 0.092 |

| Syncope | 450 (6.3) | 37 (6.6) | 109 (7.6) | 76 (6.2) | 612 (6.4) | 0.449 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 338 (4.7) | 36 (6.4) | 65 (4.5) | 66 (5.4) | 523 (5.5) | 0.091 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 146 (2) | 9 (1.6) | 29 (2) | 18 (1.5) | 201 (2.1) | 0.603 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 823 (11.4) | 63 (11.2) | 175 (12.2) | 159 (13) | 1162 (12.1) | 0.449 |

| Asthma or COPD | 1888 (26.2) | 144 (25.5) | 374 (26) | 280 (22.8) | 2181 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 740 (10.3) | 68 (12.1) | 128 (8.9) | 115 (9.4) | 809 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Hyperparathyroidism | 68 (0.9) | 6 (1.1) | 12 (0.8) | 10 (0.8) | 104 (1.1) | 0.774 |

| Diabetes | 517 (7.2) | 42 (7.4) | 122 (8.5) | 87 (7.1) | 597 (6.2) | 0.01 |

| Renal disease | 1658 (23.1) | 144 (25.5) | 330 (23) | 272 (22.2) | 2223 (23.2) | 0.631 |

| Prescription drug use | ||||||

| Corticosteroid use | 1014 (14.1) | 78 (13.8) | 202 (14.1) | 150 (12.2) | 1126 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 514 (7.1) | 47 (8.3) | 97 (6.8) | 136 (11.1) | 811 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| β-Blocker use | 2311 (32.1) | 202 (35.8) | 451 (31.4) | 380 (31) | 3136 (32.8) | 0.223 |

| Benzodiazepine use | 1319 (18.3) | 97 (17.2) | 231 (16.1) | 182 (14.8) | 1371 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Anticonvulsant use | 47 (0.7) | 4 (0.7) | 8 (0.6) | 8 (0.7) | 65 (0.7) | 0.989 |

| Thiazide | 1059 (14.7) | 71 (12.6) | 208 (14.5) | 170 (13.9) | 1383 (14.5) | 0.67 |

| Gastroprotective agent use | 2463 (34.2) | 201 (35.6) | 472 (32.8) | 401 (32.7) | 2857 (29.9) | <0.001 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use | 960 (13.3) | 89 (15.8) | 199 (13.8) | 177 (14.4) | 1167 (12.2) | 0.01 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise noted. P values are based on χ2 test for categorical covariates and ANOVA for continuous covariates. Covariates identified by pharmacy and medical claims within 365 d before treatment initiation.

As shown in Table 2, most observation time fell into the lowest and highest adherence categories. Using instantaneous PDC as a measure of adherence, 49% of follow-up time was in the 0–19% PDC range and 38% in the 80–100% PDC range. These percentages were reduced to 32 and 37% using cumulative PDC as a measure, because more person-time was assigned to intermediate PDC categories.

Table 2.

Annual fracture rates (per 1000 person-years) by adherence category

| Person-years | All sites

|

Hip

|

Humerus

|

Vertebral

|

Distal forearm

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Rate (CI) | n | Rate (CI) | n | Rate (CI) | n | Rate (CI) | n | Rate (CI) | ||

| Instantaneous PDC | |||||||||||

| 0–19% | 23,984 | 1149 | 48 (45–51) | 382 | 15 (13–16) | 152 | 6 (5–7) | 430 | 17 (16–19) | 221 | 9 (8–10) |

| 20–39% | 985 | 41 | 42 (30–56) | 11 | 10 (6–18) | 7 | 7 (3–13) | 18 | 18 (11–27) | 6 | 6 (2–12) |

| 40–59% | 2,524 | 98 | 39 (32–47) | 30 | 11 (8–16) | 6 | 2 (1–5) | 39 | 15 (11–20) | 17 | 6 (4–10) |

| 60–79% | 2,494 | 99 | 40 (32–48) | 33 | 12 (9–17) | 13 | 5 (3–8) | 34 | 13 (9–18) | 20 | 8 (5–11) |

| 80–100% | 18,574 | 701 | 38 (35–41) | 220 | 11 (10–13) | 87 | 4 (4–5) | 220 | 11 (10–13) | 151 | 8 (7–9) |

| Short-term cumulative PDC | |||||||||||

| 0–19% | 22,092 | 1070 | 48 (46–51) | 359 | 15 (14–17) | 137 | 6 (5–7) | 401 | 17 (16–19) | 203 | 9 (8–10) |

| 20–39% | 2,142 | 101 | 47 (39–57) | 31 | 14 (9–19) | 15 | 7 (4–11) | 37 | 17 (12–23) | 21 | 9 (6–14) |

| 40–59% | 2,419 | 92 | 38 (31–46) | 27 | 11 (7–15) | 14 | 5 (3–9) | 35 | 14 (10–19) | 15 | 6 (3–9) |

| 60–79% | 3,987 | 139 | 35 (29–41) | 40 | 9 (7–13) | 12 | 3 (2–5) | 53 | 13 (10–17) | 30 | 7 (5–10) |

| 80–100% | 17,920 | 686 | 38 (35–41) | 219 | 12 (10–13) | 87 | 5 (4–6) | 215 | 12 (10–13) | 146 | 8 (7–9) |

| Cumulative PDC | |||||||||||

| 0–19% | 15,446 | 775 | 50 (47–54) | 259 | 16 (14–18) | 116 | 7 (6–8) | 286 | 18 (16–20) | 135 | 8 (7–10) |

| 20–39% | 5,498 | 237 | 43 (38–49) | 76 | 13 (10–16) | 24 | 4 (3–6) | 94 | 16 (13–20) | 58 | 10 (8–13) |

| 40–59% | 4,292 | 176 | 41 (35–47) | 58 | 13 (10–16) | 20 | 4 (3–7) | 62 | 14 (11–18) | 32 | 7 (5–10) |

| 60–79% | 5,588 | 232 | 42 (36–47) | 68 | 11 (9–14) | 29 | 5 (3–7) | 84 | 14 (12–18) | 45 | 8 (6–10) |

| 80–100% | 17,737 | 668 | 38 (35–41) | 215 | 11 (10–13) | 76 | 4 (3–5) | 215 | 12 (10–13) | 145 | 8 (7–9) |

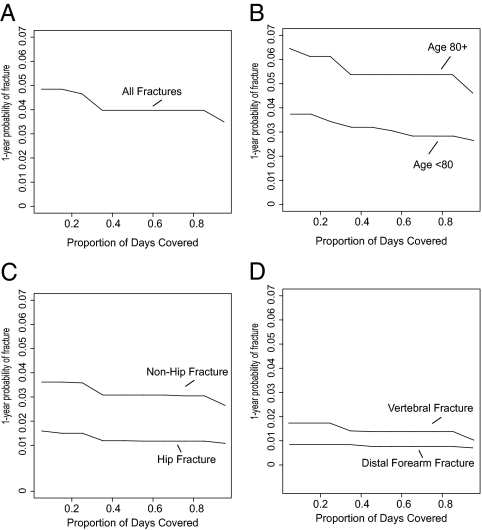

During 48,561 person-years of follow-up, 2088 patients experienced a fracture, at an incidence rate of 43 fractures per 1000 person-years. Hip (n = 676), vertebral (n = 741), and distal forearm (n = 415) fractures predominated. The overall fracture rate was lowest in patient intervals with 80–100% cumulative PDC [38 per 1000 person-years, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 35–41] and highest in intervals with 0–19% cumulative PDC (50 per 1000 person-years, 95% CI = 47–54), with intermediate rates observed in the middle adherence categories. A similar inverse correlation between adherence and overall fracture risk was observed across categories of instantaneous and short-term cumulative PDC. As seen in Table 2 and Fig. 2, this trend appeared to persist within individual fracture types, with the exception of distal forearm fractures.

Figure 2.

Isotonic regression of fracture risk on adherence. A, Risk of the composite all site outcome; B, risk of the composite outcome by age (≥80 vs. <80 yr); C and D, risk by fracture type.

Risk ratios comparing higher adherence levels to 0–19% adherence are presented in Tables 3–5. High cumulative adherence (80–100%) was associated with a 26% reduction (95% CI = 18–33%) in overall fracture risk in unadjusted analysis. This comparison for hip (28% reduction) and vertebral fractures (33% reduction) was consistent with the overall trend, but there was no apparent association between adherence and distal forearm fracture. Apparent risk reductions were attenuated slightly by adjustment for baseline covariates, with reduced fracture risk reduction for overall fractures (22% reduction), hip (23% reduction), and vertebral (26% reduction). Similar results were obtained using instantaneous and short-term cumulative adherence measures, with some variation in point estimates. In an analysis of the effects of instantaneous PDC adjusted for cumulative PDC, estimates of the instantaneous effect were attenuated to the null. For example, the estimated effect of 80–100% instantaneous PDC on all fractures combined was attenuated from a 17% to a 9% reduction. This suggests that instantaneous adherence affects fracture risk primarily as a proxy for cumulative adherence. Although fracture rates were higher among older (age ≥ 80 yr) vs. younger (age 65–79 yr) patients, the relation between adherence and fracture risk was similar (Fig. 2B). Among patient aged 80 yr or older, 80–100% adherence was associated with a significant 21% reduction in overall fracture risk and a 25% reduction in hip fracture risk (results not shown).

Table 3.

Fracture hazard ratios by cumulative PDC

| Fracture type

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All sites | Hip | Nonhip | Humerus | Vertebral | Nonvertebral | Distal forearm | |

| Unadjusted hazard ratios | |||||||

| Cumulative PDC | |||||||

| 0–19% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 20–39% | 0.84 (0.72–0.97) | 0.80 (0.62–1.04) | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 0.52 (0.33–0.82) | 0.94 (0.75–1.19) | 0.80 (0.67–0.95) | 1.22 (0.90–1.67) |

| 40–59% | 0.81 (0.69–0.95) | 0.78 (0.59–1.04) | 0.83 (0.69–1.00) | 0.60 (0.38–0.97) | 0.77 (0.59–1.02) | 0.86 (0.71–1.04) | 0.91 (0.62–1.33) |

| 60–79% | 0.82 (0.71–0.95) | 0.72 (0.55–0.94) | 0.83 (0.71–0.99) | 0.67 (0.45–1.01) | 0.82 (0.64–1.05) | 0.79 (0.67–0.95) | 0.91 (0.64–1.27) |

| 80–100% | 0.74 (0.67–0.82) | 0.72 (0.60–0.87) | 0.76 (0.67–0.85) | 0.56 (0.42–0.75) | 0.67 (0.56–0.80) | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) | 0.94 (0.75–1.20) |

| Multivariate adjusted hazard ratiosa | |||||||

| Cumulative PDC | |||||||

| 0–19% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 20–39% | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | 0.82 (0.63–1.06) | 0.90 (0.76–1.06) | 0.52 (0.33–0.82) | 0.94 (0.75–1.19) | 0.80 (0.67–0.96) | 1.22 (0.89–1.66) |

| 40–59% | 0.83 (0.7–0.98) | 0.81 (0.61–1.08) | 0.85 (0.71–1.03) | 0.61 (0.38–0.98) | 0.81 (0.62–1.07) | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) |

| 60–79% | 0.86 (0.74–1.00) | 0.76 (0.58–0.99) | 0.87 (0.74–1.04) | 0.69 (0.46–1.04) | 0.88 (0.69–1.13) | 0.82 (0.69–0.98) | 0.92 (0.65–1.29) |

| 80–100% | 0.78 (0.7–0.87) | 0.77 (0.64–0.92) | 0.80 (0.71–0.91) | 0.57 (0.42–0.76) | 0.74 (0.62–0.88) | 0.79 (0.70–0.89) | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) |

The composite all-site outcome includes hip, nonhip femur, humerus, tibia/fibula, proximal forearm, distal forearm, clavicle/scapula, sternum, spine, and pelvis fractures. Hip fractures are excluded from the nonhip outcome, and vertebral fractures are excluded from the nonvertebral outcome.

Estimates are adjusted for the covariates presented in Table 1.

Table 4.

Fracture hazard ratios by short-term cumulative PDC

| Fracture type

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All sites | Hip | Nonhip | Humerus | Vertebral | Nonvertebral | Distal forearm | |

| Unadjusted hazard ratios | |||||||

| Cumulative PDC | |||||||

| 0–19% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 20–39% | 0.95 (0.78–1.17) | 0.84 (0.58–1.22) | 1.02 (0.81–1.29) | 1.07 (0.50–2.29) | 0.98 (0.7–1.37) | 0.95 (0.74–1.21) | 1.05 (0.67–1.64) |

| 40–59% | 0.76 (0.62–0.95) | 0.67 (0.45–0.99) | 0.83 (0.65–1.05) | 0.36 (0.16–0.81) | 0.80 (0.57–1.13) | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) | 0.66 (0.39–1.12) |

| 60–79% | 0.72 (0.60–0.86) | 0.60 (0.43–0.84) | 0.75 (0.61–0.91) | 0.82 (0.47–1.42) | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | 0.71 (0.57–0.87) | 0.84 (0.57–1.22) |

| 80–100% | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.75 (0.63–0.89) | 0.81 (0.72–0.90) | 0.72 (0.56–0.95) | 0.67 (0.57–0.80) | 0.83 (0.74–0.93) | 0.89 (0.71–1.10) |

| Multivariate adjusted hazard ratiosa | |||||||

| Cumulative PDC | |||||||

| 0–19% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 20–39% | 0.99 (0.80–1.21) | 0.88 (0.60–1.28) | 1.05 (0.83–1.33) | 1.11 (0.65–1.90) | 1.01 (0.72–1.43) | 0.98 (0.77–1.25) | 1.06 (0.68–1.67) |

| 40–59% | 0.80 (0.65–0.99) | 0.71 (0.48–1.05) | 0.86 (0.68–1.10) | 0.93 (0.53–1.61) | 0.85 (0.6–1.2) | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) | 0.67 (0.40–1.14) |

| 60–79% | 0.76 (0.64–0.91) | 0.65 (0.47–0.90) | 0.79 (0.64–0.96) | 0.53 (0.30–0.94) | 0.81 (0.61–1.08) | 0.74 (0.60–0.92) | 0.85 (0.58–1.25) |

| 80–100% | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | 0.80 (0.67–0.95) | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) | 0.79 (0.60–1.05) | 0.74 (0.62–0.88) | 0.86 (0.77–0.97) | 0.90 (0.72–1.12) |

The composite all site outcome includes hip, nonhip femur, humerus, tibia/fibula, proximal forearm, distal forearm, clavicle/scapula, sternum, spine, and pelvis fractures. Hip fractures are excluded from the nonhip outcome and vertebral fractures are excluded from the nonvertebral outcome.

Estimates are adjusted for the covariates presented in Table 1.

Table 5.

Fracture hazard ratios by instantaneous PDC

| Fracture type

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All sites | Hip | Nonhip | Humerus | Vertebral | Nonvertebral | Distal forearm | |

| Unadjusted hazard ratios | |||||||

| Instantaneous PDC | |||||||

| 0–19% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 20–39% | 0.87 (0.64–1.18) | 0.87 (0.51–1.48) | 0.91 (0.64–1.29) | 1.07 (0.50–2.29) | 1.02 (0.64–1.64) | 0.87 (0.60–1.25) | 0.75 (0.35–1.59) |

| 40–59% | 0.80 (0.65–0.98) | 0.68 (0.46–0.99) | 0.83 (0.66–1.05) | 0.36 (0.16–0.81) | 0.90 (0.65–1.24) | 0.73 (0.57–0.94) | 0.76 (0.47–1.22) |

| 60–79% | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 0.78 (0.54–1.11) | 0.87 (0.70–1.09) | 0.82 (0.47–1.42) | 0.80 (0.58–1.12) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.86 (0.55–1.34) |

| 80–100% | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | 0.75 (0.63–0.88) | 0.79 (0.71–0.88) | 0.72 (0.56–0.95) | 0.66 (0.56–0.78) | 0.82 (0.73–0.92) | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) |

| Multivariate adjusted hazard ratiosa | |||||||

| Instantaneous PDC | |||||||

| 0–19% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 20–39% | 0.91 (0.67–1.23) | 0.92 (0.54–1.56) | 0.95 (0.67–1.34) | 1.11 (0.52–2.37) | 1.07 (0.67–1.72) | 0.90 (0.63–1.30) | 0.77 (0.36–1.64) |

| 40–59% | 0.84 (0.69–1.04) | 0.73 (0.50–1.08) | 0.87 (0.69–1.10) | 0.37 (0.16–0.85) | 0.96 (0.70–1.32) | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) | 0.77 (0.48–1.25) |

| 60–79% | 0.87 (0.72–1.07) | 0.83 (0.58–1.19) | 0.92 (0.73–1.15) | 0.86 (0.49–1.48) | 0.87 (0.62–1.21) | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | 0.87 (0.56–1.37) |

| 80–100% | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | 0.80 (0.67–0.94) | 0.84 (0.75–0.94) | 0.75 (0.57–0.98) | 0.72 (0.61–0.85) | 0.85 (0.76–0.96) | 0.90 (0.72–1.11) |

The composite all site outcome includes hip, nonhip femur, humerus, tibia/fibula, proximal forearm, distal forearm, clavicle/scapula, sternum, spine, and pelvis fractures. Hip fractures are excluded from the nonhip outcome and vertebral fractures are excluded from the nonvertebral outcome.

Estimates are adjusted for the covariates presented in Table 1.

Isotonic regression was used to predict 1-yr fracture risk as a function of cumulative adherence. These predicted values for the total population are presented in Fig. 2A. Although absolute fracture risks are higher in subjects age 80 yr and over compared with subjects aged 65–80 yr, the shape of the adherence-effectiveness curve in these age groups is similar (Fig. 2B). One-year hip fracture incidence is inversely associated with PDC (Fig. 2C), but there is no association between 1-yr wrist fracture incidence and PDC (Fig. 2D).

Discussion

Among a cohort of 19,987 elderly Pennsylvania Medicare beneficiaries followed for up to 5 yr, we observed an inverse relation between bisphosphonate adherence and overall fracture risk. The association was similar across the three different definitions of adherence, which ranged from an instantaneous measure based on only the past 60 d to a cumulative measure based on the entire period since bisphosphonate initiation. This similarity across measures likely results from a fairly high correlation between the three adherence measures we tested. This is supported by the finding that the apparent effect of instantaneous PDC on fracture risk is attenuated by adjustment for cumulative PDC. A similar relation was observed across different age groups. However, the association appeared to differ across anatomic sites, with evidence for a relation between adherence and hip fracture risk, but no evidence between adherence and distal forearm fracture risk.

Our results regarding the relation between adherence and risk of any osteoporotic fracture are generally consistent with previously published data. In our study, high adherence (≥80% PDC) was associated with a 17–33% reduction in fracture risk relative to low adherence (0–19% PDC), depending on the adherence measure used, consistent with the findings of studies using similar adherence categories (19,20). The roughly monotonic negative association that we observed between adherence and fracture risk is also consistent with the literature, although several studies treated adherence levels less than 50% as a single category, preventing an assessment of whether risks are differential between 0 and 49% adherence (7,21,22,23,24). Data regarding fracture risks by anatomic site are more limited. One recently published study compared site-specific fracture risks between nonadherent (<50% medication possession ratio) vs. adherent (≥80%) periods and found that nonadherence was associated with an increased risk of hip, clinical vertebral, and nonvertebral fractures among patients 78 yr or younger but was not increased with an increased risk of distal forearm fracture among any age group. Nonadherence did not increase the risk of hip fracture among patients older than 78 yr (7). Using narrower adherence categories, we found similar patterns of association between adherence and the risk of hip, clinical vertebral, and nonvertebral fractures and no association between adherence and the risk of distal forearm fracture. We did find a significant 25% hip fracture risk reduction in our oldest age group (age ≥ 80 yr). Our point estimate and confidence interval overlap those of this recent study, suggesting that our results are not inconsistent. Because our study population is enriched with the very old, we observed more events in this age group, affording us greater power to detect a difference.

Our study benefits from several strengths. We were able to include multiple years of data for a large population of nearly 20,000 elderly bisphosphonate initiators. Due to low turnover rates, the average follow-up time in our study was 3 yr, even with follow-up capped at 5 yr. Prescriptions in our database are typically 30 d or shorter, which likely increases our ability to accurately assess adherence, relative to a database with longer prescription durations.

Despite these strengths, several limitation should be noted. First, our ability to assess adherence effects by fracture type and patient subgroup is limited by small numbers of outcomes. Second, some misclassification of both bisphosphonate exposure and fracture outcomes is possible. Adherence could be overestimated if patients fill prescriptions but do not take them as prescribed and underestimated if some apparently nonadherent patients receive free samples. Fracture outcomes could also be misclassified. However, the combinations of diagnosis and procedure codes used in our study had positive predictive values ranging from 94% (all fractures) to 98% (hip fracture) relative to medical chart review in a validation study (13). Furthermore, there is little reason to believe that outcome misclassification would be differential across adherence levels. Lastly, our study may suffer from confounding by factors that are unmeasured in our dataset including frailty, baseline bone mineral density, calcium and vitamin D use, and cognitive function. If patients who are at higher risk of fracture are more adherent, then our results may underestimate the association between adherence and fracture risk reduction from oral bisphosphonates. Alternatively, if patients who adhere to bisphosphonates are less frail and/or more likely to engage in other behaviors that improve bone mineral density or reduce the risk of falls, the relation between adherence and fracture reduction would be overstated in our findings. Selection bias related to unmeasured characteristics of patients who tend to adhere to therapy, the healthy adherer effect, is a well described phenomenon (10). However, this phenomenon has not been well studied in the osteoporosis field. An analysis of the placebo arm of the Women’s Health Initiative found that adherence to placebo in this study was associated with a 50% reduction in hip fracture (25). However, it is likely that elderly patients receiving bisphosphonates are more homogeneous in their fracture risk than the younger and more diverse population represented in Women’s Health Initiative, making a study in this population less susceptible to healthy adherer bias (26).

In addition to the possible limitations noted above, our results may be limited in generalizability. Our cohort was restricted to subjects age 65 yr and over enrolled in a state-run drug benefit plan for lower-income patients. To the extent that bisphosphonate effectiveness varies by age, our results may not generalize to younger populations. Although the restriction by income seems likely to improve the internal validity of our findings by reducing the possibility of variation in adherence by socioeconomic status, it is possible that this restriction resulted in the selection of patients who are older than the average age 65 plus population.

Our results suggest that adherence to bisphosphonates is associated with a reduced risk of fracture, with the possible exception of distal forearm fracture. These findings were not influenced by the length of the adherence assessment period, likely because of the correlation between instantaneous and cumulative adherence measures. However, due to potential confounding by unmeasured patient characteristics such as frailty and fracture risk, there remains uncertainty about the interpretation of observational data on the relation between bisphosphonate adherence and fracture reduction.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (P60 AR 047782 and K24 AR055989). S.M.C. holds a New Investigator Award in the Area of Aging and Osteoporosis from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Disclosure Summary: A.R.P., E.L., J.T.S., S.M.C., H.M., and D.H.S. have nothing to declare. M.A.B. sat on advisory boards for Amgen, received investigator-initiated grant support from Amgen, and receives research support from the GlaxoSmithKline SK Center for Excellence in Pharmacoepidemiology at University of North Carolina.

First Published Online May 5, 2010

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PACE, Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly; PDC, proportion of days covered.

References

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A 2007 Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22:465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranney A, Guyatt G, Griffith L, Wells G, Tugwell P, Rosen C 2002 Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. IX. Summary of meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev 23:570–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ 2007 Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ström O, Borgström F, Kanis JA, Jönsson B 2009 Incorporating adherence into health economic modelling of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 20:23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DA, Bagust A, Haycox A, Walley T 2001 The impact of non-compliance on the cost-effectiveness of pharmaceuticals: a review of the literature. Health Econ 10:601–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi J, Lynch N, Middelhoven H, Hunjan M, Cowell W 2007 The association between compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy and fracture risk: a review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 8:97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E 2008 Benefit of adherence with bisphosphonates depends on age and fracture type: results from an analysis of 101,038 new bisphosphonate users. J Bone Miner Res 23:1435–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ 2003 Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in Medicare populations. Health Serv Res 38:1103–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA 1992 Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Dormuth C, Avorn J, Shrank W, Cadarette SM, Solomon DH 2007 Adherence to lipid-lowering therapy and the use of preventive health services: an investigation of the healthy user effect. Am J Epidemiol 166:348–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, Palermo L, Prineas R, Rubin SM, Scott JC, Vogt T, Wallace R, Yates AJ, LaCroix AZ 1998 Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 280:2077–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron JA, Lu-Yao G, Barrett J, McLerran D, Fisher ES 1994 Internal validation of Medicare claims data. Epidemiology 5:541–544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML 1992 Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. J Clin Epidemiol 45:703–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Mudano AS, Solomon DH, Xi J, Melton ME, Saag KG 2009 Identification and validation of vertebral compression fractures using administrative claims data. Med Care 47:69–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Taylor AJ, Matthews RS, Ray MN, Becker DJ, Gary LC, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Saag KG, Warriner A, Delzell E 2009 “Pathologic” fractures: should these be included in epidemiologic studies of osteoporotic fractures? Osteoporos Int 20:1969–1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK 2008 Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 11:44–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team 2005 R: A language and environment for statistical computing, reference index version 2.2.1. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- Robertson T, Wright FT and Dykstra RL 1988 Order restricted statistical inference. New York: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Yood RA, Kahler KH 2007 Consequences of poor compliance with bisphosphonates. Bone 41:882–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weycker D, Macarios D, Edelsberg J, Oster G 2007 Compliance with osteoporosis drug therapy and risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int 18:271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin J, Dragomir A, Moride Y, Ste-Marie LG, Fernandes JC, Perreault S 2008 Impact of noncompliance with alendronate and risedronate on the incidence of nonvertebral osteoporotic fractures in elderly women. Br J Clin Pharmacol 66:117–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ 2006 Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 38:922–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning-van Beest FJ, Erkens JA, Olson M, Herings RM 2008 Loss of treatment benefit due to low compliance with bisphosphonate therapy. Osteoporos Int 19:511–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA, Silverman S 2006 Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis J, Larson J, Delzell E, Judd S, Safford MM, LaCroix A, Chlebowski R 2009 Does the benefit of medication adherence relate more to a drug effect or the behavior itself? Quantifying the effect of adherence behavior using data from the placebo arm of the WHI. Arthritis Rheum 60:613 [Google Scholar]

- Cadarette S, Solomon D, Katz J, Patrick A, Brookhart M 2010 Adherence to osteoporosis drugs and fracture prevention: no evidence of healthy adherer bias in a frail cohort of seniors. Can J Clin Pharmacol 17:e92 (Abstract) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]