Abstract

Context: Adiponectin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue, has both metabolic and antiinflammatory properties. Although multiple studies have described the relationship between adiponectin and obesity in several human populations, no large studies have evaluated this relationship in Africans.

Objective: We investigated the relationship between adiponectin and measures of obesity, serum lipids, and insulin resistance in a large African cohort.

Design: Participants are from the Africa America Diabetes Mellitus (AADM) Study, a case-control study of genetic and other risk factors associated with development of type 2 diabetes in Africans.

Setting: Patients were recruited from five academic medical centers in Nigeria and Ghana (Accra and Kumasi in Ghana and Enugu, Ibadan, and Lagos in Nigeria) over 10 yr.

Main Outcome Measures: Circulating adiponectin levels were measured in 690 nondiabetic controls using an ELISA. The correlation between log-transformed circulating adiponectin levels and age, gender, measures of obesity (body mass index, waist circumference, and percent fat mass), and serum lipid levels was assessed. Linear regression was used to explore the association between adiponectin levels and measures of obesity, lipids, and insulin resistance as measured by homeostasis model assessment.

Results: Significant negative associations were observed between log-adiponectin levels and measures of obesity after adjusting for age and gender. Similarly, log-adiponectin levels were significantly negatively associated with serum triglycerides and insulin resistance but positively associated with high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and total cholesterol after adjusting for age, gender, and body mass index.

Conclusions: Circulating adiponectin is significantly associated with measures of obesity, serum lipids, and insulin resistance in this study of West African populations.

Adiponectin is negatively associated with body mass index, waist circumference, percent fat mass, triglycerides, and insulin resistance and positively associated with HDL-C in West Africans.

Obesity is a current and growing public health problem. By 2015, obesity is projected to affect 700 million people, a significant proportion of whom will reside in urban settings of developing countries (1). Obesity is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, which are the leading global cause of death for both men and women (1). Furthermore, maternal obesity at birth increases the risk of childhood incidence of metabolic syndrome, perpetuating a cycle of obesity and obesity-related comorbidities (2).

New understanding of adipose tissue has illuminated the development of obesity and its effect on metabolic and inflammatory processes (3). A major paradigm shift in the study of adipose tissue resulted from the discovery that it is more than a reservoir of fat for energy; rather, it functions as an endocrine tissue that secretes several bioactive molecules responsible for regulating metabolism and inflammation (3,4). Adiponectin, one such peptide, is secreted abundantly into plasma. It possesses insulin-sensitizing and antiatherosclerotic properties (5,6). Unlike other adipose-derived hormones such as leptin and resistin, which correlate positively with measures of adiposity, adiponectin inversely associates with obesity in rodents and humans (4,5,7). Furthermore, increased levels of adiponectin have been associated with improved insulin sensitivity, skeletal muscle fatty oxidation, and energy dissipation (6,8). Although it does not correlate with most other cytokines, it is inversely related to levels of TNF-α (8). In addition to having protective metabolic properties, its antiinflammatory properties have antiatherosclerotic effects; in fact, adiponectin suppresses the migration of monocytes and their transformation into foam cells (9,10). Adiponectin may protect against myocardial infarctions and cancer (11,12).

To our knowledge, there are three published epidemiological studies of adiponectin in continental African populations. Ferris et al. (13) studied 111 South Africans and reported that whites had higher levels of adiponectin and were less insulin resistant than Black and Indian subjects. Sobngwi et al. (14) examined 70 Cameroonians and found that although adiponectin levels were inversely correlated with waist circumference (WC), fat mass, and insulin resistance, the former two relationships did not remain significant in women once adjusted for gender. Ntyintyane et al. (15) studied 60 Black South Africans and showed a positive correlation between leptin and body mass index (BMI), WC, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein but did not find a significant association with these measures and adiponectin. We studied the relationship between adiponectin and measures of obesity in a large, well-characterized sample of nondiabetic West Africans. Furthermore, we explored the relationship between adiponectin and serum lipid levels in view of the increasing body of evidence showing a relationship between adiponectin and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglycerides (TG) (3,16).

Patients and Methods

The study included nondiabetic participants from a sample of unrelated West Africans enrolled as controls in the AADM Study (17). After obtaining written informed consent, participants underwent an interview followed by a physical examination during which weight, height, BMI, WC, percent fat mass (PFM), serum lipid levels, and insulin resistance were measured as described elsewhere (17).

Adiponectin was assayed using the ELISA kit Quantikine human adiponectin immunoassay (catalog item DRP300) from R&D Systems Inc., (Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Insulin resistance was estimated using homeostasis model assessment (18) in a subset (n = 371) of the study participants.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 17.0). The distribution of adiponectin levels was log10 transformed to remove positive skew. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were estimated to assess the relationship between log adiponectin and age, BMI, WC, PFM, and serum lipid fractions (total cholesterol, HDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and TG). Multiple linear regression models were used to examine the relationship between adiponectin levels and measures of obesity, lipids, and insulin resistance while adjusting for covariates. Eleven linear regression models were considered. Therefore, to adjust for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni corrected P value threshold of 0.05/11 = 0.005 was used to assess statistical significance in the linear regression analyses. To assess whether a statistically significant difference in adiponectin existed by country of origin (Ghana vs. Nigeria), an analysis of covariance was performed. The data were split by country of origin to identify the amount of variance explained by country of origin while controlling for age, sex, and BMI using multiple linear regression.

Results

Characteristics of study sample

The study sample comprised 690 individuals of whom 59% were women. On average, men were about 3 yr older than women (47.0 ± 14.6 vs. 44.0 ± 12.5 yr, P = 0.004). Descriptive statistics by gender for age, BMI, WC, PFM, and adiponectin are presented in Table 1. On average, women were significantly more obese than men, indicated by an increased (compared with men) mean BMI of approximately 3.5 kg/m2, an increased mean WC of approximately 3 cm, and an increased mean PFM of approximately 17%. Adiponectin levels were significantly lower in men compared with women (geometric mean 5.23 μg/ml vs. 6.94 μg/ml, P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Mean values of demographic variables and differences in measures of adiposity between men and women

| Variable | Men | Women | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 275 | 398 | |

| Age (yr) | 47.0 (14.5) | 43.9 (12.5) | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.70 (4.16) | 27.12 (5.96) | <0.0001 |

| WC (cm) | 86.4 (12.3) | 89.2 (17.2) | 0.008 |

| PFM (%) | 17.62 (13.60) | 34.84 (12.60) | <0.0001 |

| Adiponectin (ng/ml) | |||

| Geometric mean | 5225.1 | 6942.2 | <0.0001 |

| Median | 5373.4 | 7609.2 | |

| Interquartile range | 3451.5–8331.2 | 4385.8–11,806.6 |

Values are means (sd).

Adiponectin correlations with age, gender, and measures of obesity

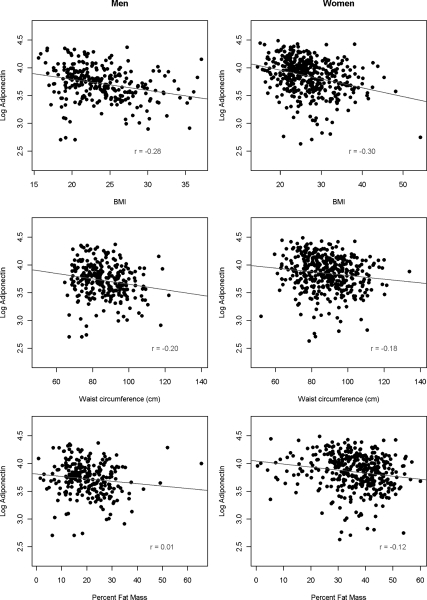

Log adiponectin levels showed a positive correlation with age (r = 0.249; P < 0.0001; Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). BMI (r = −0.2030; P < 0.0001) and WC (r = −0.154; P < 0.0001) were negatively correlated with log adiponectin levels (Fig. 1) in both men and women, whereas PFM was significantly negatively correlated with log adiponectin levels only in women (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1.

Log adiponectin by BMI, WC, and PFM in West Africans.

Adiponectin associations with measures of obesity

In four separate multiple linear regression models, each of the measures of obesity (BMI, WC, and PFM) was independently associated with log adiponectin levels; age, gender, and country remained significant covariates in these models. The model with BMI explained the most variance in log adiponectin levels (adjusted r2 = 0.195), in contrast to those with WC (adjusted r2 = 0.165) and PFM (adjusted r2 = 0.122) (Supplemental Table 2).

Adiponectin associations with serum lipids, insulin resistance, and country of origin

All three lipid measures, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and TG, were significantly associated with log adiponectin levels while controlling for age, gender, country, and BMI (Supplemental Table 3). Total cholesterol and HDL-C were positively associated with log adiponectin levels, whereas TG was negatively associated with adiponectin levels (Supplemental Table 3). Differences in mean adiponectin and serum lipid levels by BMI are presented in Supplemental Fig. 2. Adiponectin was significantly and negatively associated with insulin resistance (homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance: β = −0.160; se = 0.005; P = 0.001) while controlling for age, gender, country, and BMI. There was a significant difference in the mean adiponectin level by country of origin (Ghanians 5073.4 and Nigerians 6692.7, P = 0.034); this difference may be due, in part, to the imbalance in the number of participants from the two countries (190 from Ghana and 490 from Nigeria) included in this study. We therefore adjusted for country in all multiple linear regression analyses.

Discussion

Increasing evidence points to the protective role of adiponectin in obesity-related complications, including ameliorating insulin resistance, diabetes, and atherosclerosis (4,8,19). Both the association of increased BMI with decreased plasma adiponectin levels and the presence of higher levels of adiponectin in women than men have been demonstrated in previous studeis (3). Furthermore, adiponectin levels have been positively associated with HDL-C and negatively with low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and TG (3), suggesting a role not only in obesity but also in dyslipidemia.

Large epidemiological studies of adiponectin and obesity are few in populations of African ancestry despite the increased prevalence of obesity in these populations. The noted paucity of data in this high-risk group is particularly relevant given that higher adiponectin levels have been reported in European and Asian populations compared with African-ancestry populations (13,16,20). Total immunoreactive adiponectin was shown to be decreased in 75 African Americans compared with 57 European Americans (21). In particular, the low molecular weight hexamer and trimer of adiponectin were reduced. These same multimers also had greater association with body composition and metabolic measures such as visceral adipose tissue, WC, HDL, fasting insulin, and insulin sensitivity, whereas the same traits showed greater association with high molecular weight multimer in European Americans (21). Although we did not evaluate multimeric forms of adiponectin, with nearly 700 subjects, this study is larger than all previous studies of adiponectin in Africans combined and thus provides the first large epidemiological analysis of the relationship between adiponectin levels and obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension in African-ancestry populations.

Both WC (a measure of central adiposity) and BMI (a measure of overall obesity) were negatively correlated with adiponectin levels, but BMI explained more of the variability in adiponectin. Overall, our findings are similar to previous observations of the inverse relationship between adiponectin levels and measures of obesity (3,4). However, unlike the previous finding in Cameroonians that WC correlated negatively with adiponectin in men but not in women (14) and that adiponectin was not significantly negatively associated with measures of obesity in either gender in Black South Africans (15), our study of West Africans shows that adiponectin levels correlate negatively with WC in both sexes. This contrast is likely due to the larger sample size of our study. As in other studies, we found that insulin resistance was significantly negatively associated with adiponectin levels (3). However, we did not have a large enough subset of subjects with metabolic syndrome to evaluate the association between plasma adiponectin and metabolic syndrome.

WC measures visceral adiposity more closely than BMI does, so our finding of BMI having the strongest correlation may be partly explained by the fact that adiponectin is expressed in tissues other than fat, such as muscle, liver, and bone marrow (http://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=ADIPOQ&search=adipoQ). Thus, because BMI takes into account total body mass and not visceral fat alone, it may better capture the relationship between obesity and adiponectin levels. The discordant relationship between PFM and adiponectin levels between men and women may be due to the fact that this study had more women, and the women had 2-fold higher PFM than the men. Adiponectin has also been shown to be decreased by the presence of androgens (22), which may in part explain the male-female differences observed in the present study.

Advances in the understanding of the role of adiponectin and its potential for therapeutic intervention are promising and particularly important in light of the epidemic of obesity, which is a growing problem in both developed and developing countries. This first large-scale epidemiological investigation of the relationship between adiponectin and measures of obesity, serum lipids, and insulin resistance in West Africans provides several interesting findings worthy of further research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health (CRGGH). The CRGGH is supported by National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Center for Information Technology, and the Office of the Director at the National Institutes of Health (Z01HG200362). Support for the Africa America Diabetes Mellitus (AADM) study is provided by National Institutes of Health Grant 3T37TW00041-03S2 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. This project is also supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources.

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

First Published Online April 9, 2010

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; PFM, percent fat mass; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference.

References

- World Health Organization 2006 Obesity and overweight. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Boney CM, Verma A, Tucker R, Vohr BR 2005 Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 115:e290–e296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LC, Huang KC, Wu YW, Kao HL, Chen CL, Lai LP, Hwang JJ, Yang WS 2009 The clinical implications of blood adiponectin in cardiometabolic disorders. J Formos Med Assoc 108:353–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juge-Aubry CE, Henrichot E, Meier CA 2005 Adipose tissue: a regulator of inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 19:547–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K 2006 Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 116:1784–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Imai Y, Shimozawa N, Hioki K, Uchida S, Ito Y, Takakuwa K, Matsui J, Takata M, Eto K, Terauchi Y, Komeda K, Tsunoda M, Murakami K, Ohnishi Y, Naitoh T, Yamamura K, Ueyama Y, Froguel P, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kadowaki T 2003 Globular adiponectin protected ob/ob mice from diabetes and ApoE-deficient mice from atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem 278:2461–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM 1996 AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J Biol Chem 271:10697–10703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern PA, Di Gregorio GB, Lu T, Rassouli N, Ranganathan G 2003 Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor-α expression. Diabetes 52:1779–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Luo N, Klein RL, Chung BH, Garvey WT, Fu Y 2009 Adiponectin reduces lipid accumulation in macrophage foam cells. Atherosclerosis 202:152–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Hori M, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Miyazaki A, Nakayama H, Horiuchi S 2004 Adiponectin down-regulates acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase-1 in cultured human monocyte-derived macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 317:831–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelesidis I, Kelesidis T, Mantzoros CS 2006 Adiponectin and cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer 94:1221–1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pischon T, Girman CJ, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Hu FB, Rimm EB 2004 Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA 291:1730–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris WF, Naran NH, Crowther NJ, Rheeder P, van der Merwe L, Chetty N 2005 The relationship between insulin sensitivity and serum adiponectin levels in three population groups. Horm Metab Res 37:695–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobngwi E, Effoe V, Boudou P, Njamen D, Gautier JF, Mbanya JC 2007 Waist circumference does not predict circulating adiponectin levels in sub-Saharan women. Cardiovasc Diabetol 6:31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntyintyane L, Panz V, Raal FJ, Gill G 2009 Leptin, adiponectin, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in relation to the metabolic syndrome in urban South African blacks with and without coronary artery disease. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 7:243–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Freedman BI, Arnett DK, Leiendecker-Foster C, Jones TL, Redden DT, Oberman A 2007 Plasma adiponectin concentrations and correlates in African Americans in the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network (HyperGEN) study. Metabolism 56:1011–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotimi CN, Dunston GM, Berg K, Akinsete O, Amoah A, Owusu S, Acheampong J, Boateng K, Oli J, Okafor G, Onyenekwe B, Osotimehin B, Abbiyesuku F, Johnson T, Fasanmade O, Furbert-Harris P, Kittles R, Vekich M, Adegoke O, Bonney G, Collins F 2001 In search of susceptibility genes for type 2 diabetes in West Africa: the design and results of the first phase of the AADM study. Ann Epidemiol 11:51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC 1985 Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Pankow JS, Bang H, Couper D, Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Heiss G 2004 Adiponectin and the development of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes 53:2473–2478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsamakis G, Chetty R, McTernan PG, Al-Daghri NM, Barnett AH, Kumar S 2003 Fasting serum adiponectin concentration is reduced in Indo-Asian subjects and is related to HDL cholesterol. Diabetes Obes Metab 5:131–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Castro C, Doud EC, Tapia PC, Munoz AJ, Fernandez JR, Hunter GR, Gower BA, Garvey WT 2008 Adiponectin multimers and metabolic syndrome traits: relative adiponectin resistance in African Americans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16:2616–2623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa H, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Maeda N, Kuriyama H, Nagaretani H, Matsuda M, Kondo H, Furuyama N, Kihara S, Nakamura T, Tochino Y, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y 2002 Androgens decrease plasma adiponectin, an insulin-sensitizing adipocyte-derived protein. Diabetes 51:2734–2741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.