Abstract

We described hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence among 2,347 pregnant women having delivered at the Cayenne hospital in 2007 according to ethnicity. With 11.0% HBsAg prevalence, Asian women (Hmong and Chinese) were the group with the highest risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) perinatal transmission compared with other ethnic groups.

An estimated 2 billion people have been infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) worldwide and between 350 and 400 million persons have chronic liver infections with the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).1 Low, intermediate, and high HBV endemicity areas are defined as prevalence of HBsAg in the general population < 2%, between 2% and 8%, and > 8%, respectively. Western Europe and North America have low endemicity, whereas the Middle East and Indian subcontinent have an intermediate endemicity. China and other parts of Asia, Eastern and Central Europe, much of Africa, and the Amazon Basin are high endemicity areas.2 French Guiana is an overseas French region located in the Amazon Basin on the northeast coast of the South American continent between Brazil and Suriname. The HBsAg prevalence is unknown in the population of French Guiana (200,000 inhabitants), which is a melting pot of a large variety of ethnic groups, including Creoles (mixed European and African descent), Amerindians, Maroons (African descent), Caucasians (from metropolitan France), and immigrants from Haiti, Suriname, Brazil, and Asian countries (Hmong and Chinese). In high endemic areas, HBV infection occurs during infancy and early childhood by either horizontal or perinatal transmission by pregnant women carrying HBsAg who act as a reservoir for HBV.3 Nevertheless, more than 90% of perinatal infections can be prevented if HBsAg-positive mothers are identified and their newborns are treated promptly after delivery with hepatitis B (HB) immune globuline and HB vaccine. To improve prevention campaigns in high endemic areas, there is a need to identify groups with high risk of HBV perinatal transmission. Our objective was, therefore, to estimate the prevalence of HBsAg during pregnancy in the various ethnic groups of French Guiana. We conducted a retrospective study of HBsAg prevalence among all pregnancies delivered in the obstetric unit of the Cayenne hospital from January 1 to December 31, 2007. Data on maternal variables (age, ethnicity, cesarean delivery, and residence site) and newborn vaccination status were collected in the registre d'issue des grossesses, which has clearance from the Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertes. All pregnant women were tested for HBsAg (Axsym HBsAg v2.0; Abbott Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany).

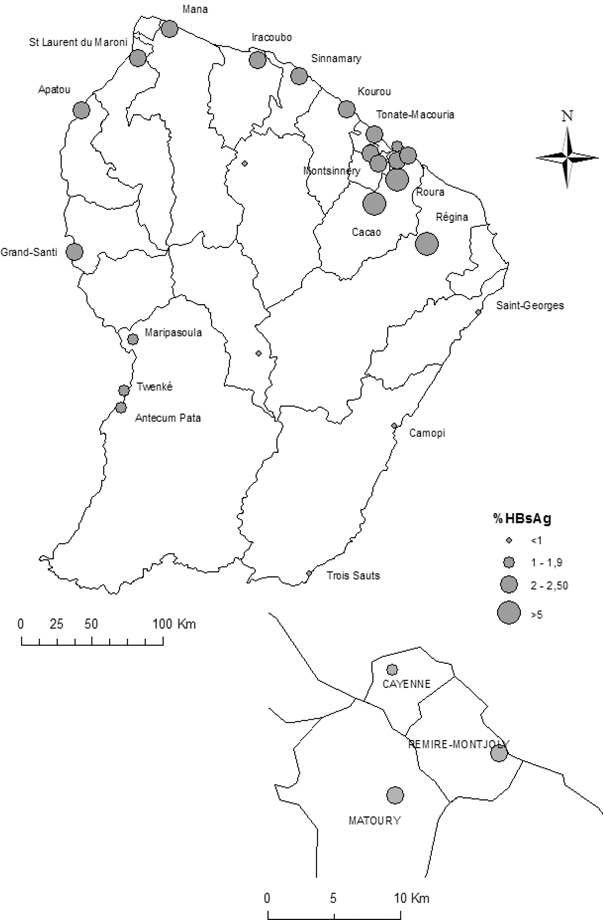

The mean age of the 2,347 women included and screened for HBsAg was 27.4 ± 7 years (range = 11–47 years). There were Asians (2.1%; N = 46), metropolitans (3.3%; N = 76), Amerindians (5.9%; N = 132), Maroons (15.2%; N = 342), Brazilians (15.6%; N = 351), Creoles (19.9%; N = 448), and Haitians (22.9%; N = 517). The ethnicity was undetermined for 14.9% of women. Nearly one-half (49%) of them lived in Cayenne, and the others lived throughout French Guiana. The overall prevalence of HBsAg positivity was 1.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.1–2.1) and varied according to ethnicities. The prevalence was higher in Asian women (Hmong and Chinese) at 11.0% (95% CI = 4.1–22.4) and lower in Amerindians at 0.8% (95% CI = 0.1–3.6) and Brazilians or Caucasians at 0.3% each (95% CI = 0.1–1.4; P < 0.0001). It was 2.3% (95% CI = 1.1–4.4) and 1.9% (95% CI = 1.0–2.7) in Maroon and Creole women, respectively (Table 1). According to the residence site, the prevalence of HBsAg was 5.7% among women living Cacao and Roura and 0.8% among those living along the Oyapock River to the east (Figure 1). There was no association between prevalence of HBsAg and residence or age (P > 0.05). There was no significant difference in HBsAg prevalence among women delivering vaginally (1.6%) and by caesarean (1.1%).

Table 1.

Prevalence of HBsAg carriage according to ethnicity

| Ethnicity | N | HBsAg positive | Percent HBsAg positive (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haitians | 517 | 13 | 2.5 (1.4–4.1) |

| Creoles | 448 | 5 | 1.1 (0.4–2.4) |

| Maroons | 429 | 9 | 2.1 (1.0–3.8) |

| Brazilians | 351 | 1 | 0.2 (0.0–1.3) |

| Asians | 46 | 5 | 11.0 (4.1–22.4) |

| Amerindians | 141 | 1 | 0.7 (0.0–3.4) |

| Caucasians | 77 | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–3.8) |

| Others | 338 | 2 | 0.6 (0.1–1.9) |

| Total | 2,347 | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) |

Figure 1.

HBV areas of endemicity in French Guiana according to HBsAg prevalence in pregnant women.

In this study, the prevalence was lower in Amerindians (0.8%) who lived mainly along rivers that serve as natural frontiers (Oyapock to the east with Brazil and Haut-Maroni to the west with Suriname). Creoles and Haitians living in the urban centers (northeast) and the Maroons living along the Bas-Maroni River to the west were in an intermediate endemic area, with prevalence between 2.0% and 2.5%. The percentage of HBsAg carriage was very high (11.0%) for southeast Asian women (Hmong and Chinese). Chinese communities of French Guiana are in Cayenne and its suburbs, and the people are descendants of Hakka settlers and immigrants from Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and continental China who began arriving in 1820. The level of HBsAg carriage in these communities is still the same as in China before mass hepatitis B vaccination.4 Hmong communities lived in Cacao and Javouhey, two villages created in 1977 by the French government for Hmong refugees from Laos and Thailand who resettled in French Guiana. Many studies in Australia and Canada assessing the burden of illness in immigrant populations many years after resettlement have shown that some important infections and hepatitis B are still common in immigrants and refugees from the Mekong region.5–7 Thus, Cacao, Regina, and Roura villages, whose populations are constituted with 80% Hmong, were the highest endemic areas, with 5.7% of pregnant women carrying HBsAg.

To evaluate the representativeness of women delivering at the Cayenne hospital, we compared their characteristics with those of a representative sample of 1,713 women who delivered in the four types of maternity centers in French Guiana (Cayenne Hospital, Saint-Laurent du Maroni Hospital, Center Medico Chirurgical de Kourou, and Clinique Veronique) and were studied by the Regional Observatory of Health (unpublished data). There were no significant differences in age, ethnicity, and caesarian rate. Transmission of HBV during the perinatal period and early childhood is the most important infection mode; the prevention of HBV infection in infants and preschool children through vaccination with the hepatitis B vaccine is the most critical strategy to control HBV infection. This strategy was successfully applied in China, one of the first two countries in the developing world to attempt to control HBV infection by mass immunization with hepatitis B vaccine.7 Hepatitis B vaccination for non-immune individuals is also important, particularly if a family member is known to be infected. People diagnosed with chronic HBV should have access to regular monitoring of complications and antiviral therapy, if necessary. This study should help the French Guiana health authorities to address priorities of prevention, screening, and treatment of HBV in the 2009–2012 national plan against hepatitis viruses B and C.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julien Renner (Cellule Iuter Regionale d'Epidemiologie Antilles Guyane) for the figure design.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Aba Mahamat, Magalie Demar, and Félix Djossou, Unité des Maladies Infectieuses et Hygiène and Groupe d'Etudes sur les Hépatites Virales, Centre Hospitalier Andrée Rosemon, Cayenne, French Guiana, E-mail: aba.mahamat@ch-cayenne.fr. Dominique Louvel, Groupe d'Etudes sur les Hépatites Virales and Service de Médecine Interne B, Centre Hospitalier Andrée Rosemon, Cayenne, French Guiana. Tania Vaz, Groupe d'Etudes sur les Hépatites Virales and Hôpital de Jour Adultes, Service de Gynécologie-Obstétrique, Centre Hospitalier Andrée Rosemon, Cayenne, French Guiana. Mathieu Nacher, Hôpital de Jour Adultes, Service de Gynécologie-Obstétrique, Centre Hospitalier Andrée Rosemon, Cayenne, French Guiana.

References

- 1.McMahon BJ. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25((Suppl 1)):3–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann CJ, Thio CL. Clinical implications of HIV and hepatitis B co-infection in Asia and Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:402–409. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu SC, Chan MH, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Lee CY. Horizontal transmission of HBV in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:66–69. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199301000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou YH, Wu C, Zhuang H. Vaccination against hepatitis B: the Chinese experience. Chin Med J. 2009;122:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyorkos TW, MacLean JD, Viens P, Chheang C, Kokoskin-Nelson E. Intestinal parasite infection in the Kampuchean refugee population 6 years after resettlement in Canada. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:413–417. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Silva S, Saykao P, Kelly H, MacIntyre CR, Ryan N, Leydon J, Biggs BA. Chronic Strongyloides stercoralis infection in Laotian immigrants and refugees 7–20 years after resettlement in Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 2002;128:439–444. doi: 10.1017/s0950268801006677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caruana S, Kelly H, de Silva S, Chea L, Nuon S, Saykao P, Bak N, Biggs BA. Knowledge about hepatitis and previous exposure to hepatitis viruses in immigrants and refugees from Mekong Region. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29:64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2005.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]