Abstract

Eukaryotic cells require iron for survival and have developed regulatory mechanisms for maintaining appropriate intracellular iron concentrations. The degradation of iron regulatory protein 2 (IRP2) in iron-replete cells is a key event in this pathway, but the E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for its proteolysis has remained elusive. We found that a SKP1-CUL1-FBXL5 ubiquitin ligase protein complex associates with and promotes the iron-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of IRP2. The F-box substrate adaptor protein FBXL5 was degraded upon iron and oxygen depletion in a process that required an iron-binding hemerythrin-like domain in its N terminus. Thus, iron homeostasis is regulated by a proteolytic pathway that couples IRP2 degradation to intracellular iron levels through the stability and activity of FBXL5.

Iron regulatory proteins 1 and 2 (IRP1 and IRP2) function as RNA-binding proteins during iron-limiting conditions in order to regulate the translation and stability of mRNAs encoding proteins required for iron homeostasis (1, 2). In iron-replete cells, IRP RNA binding is reduced because of the assembly of a 4Fe-4S cluster in IRP1 (3) and the proteasomal degradation of IRP2 (4–7). Despite the importance of IRP2 in iron metabolism, the ubiquitin ligase responsible for its degradation remains unclear. Early studies suggested that a unique 73-aminoacid region of IRP2 was a substrate for the haemoxidized IRP2 ubiquitin ligase (HOIL-1) (8, 9). Other studies, however, showed that deletion of the 73-amino-acid region or HOIL-1 silencing did not affect the iron-dependent degradation of IRP2 (10–12).

Human FBXL5 is a member of the F-box family of adaptor proteins that confer substrate specificity to SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box) ubiquitin ligases (13, 14). FBXL5 contains a hemerythrin-like domain, a F-box domain that mediates its association with SKP1, and four leucine-rich repeats that probably function in substrate binding (fig. S1). Affinity purification followed by multidimensional protein identification technolology (MudPIT) (15, 16) was used to identify proteins that interact with a mutant form of FBXL5 lacking the F-box domain, which cannot assemble into an active SCF complex (17). Because this mutant retains the ability to interact with substrates but is unable to catalyze their ubiquitination, it functions as a substrate-trapping reagent. IRP1 and IRP2 were identified as FBXL5-interacting proteins in this analysis (table S1). A reciprocal proteomic analysis showed that FBXL5, SKP1, and CUL1 copurify with IRP2 (table S1).

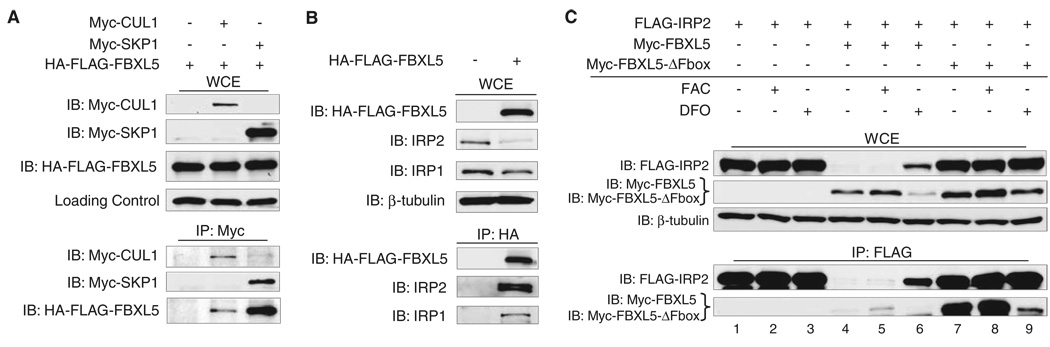

We confirmed the interaction of FBXL5 with SCF components and IRPs using coimmunoprecipitation analyses (17). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells stably expressing hemagglutinin (HA)–FLAG-FBXL5 were transfected withMyc-CUL1 or Myc-SKP1. HA-FLAG-FBXL5 copurified with immunoprecipitated Myc-CUL1 and Myc-SKP1 (Fig. 1A). For the FBXL5-IRP interactions, HA-FLAG-FBXL5 was immunoprecipitated from stable HEK293 cells. Endogenous IRP1 and IRP2 copurified only in extracts containing HA-FLAG-FBXL5 (Fig. 1B). We found that the 73-amino-acid region of IRP2 was not required for the interaction with FBXL5 (fig. S2). Thus, FBXL5 is a component of a bona fide SCF complex that interacts with IRP1 and IRP2.

Fig. 1.

FBXL5 forms a SCF complex that associates with IRP1 and IRP2. (A) Flp-In TREx-293 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) stably expressing HA-FLAG-FBXL5 were transfected with Myc-CUL1, Myc-SKP1, or empty vector. Myc-CUL1 and Myc-SKP1 were immunoprecipitated with antibody to c-Myc. Whole-cell extracts (WCEs) and immunoprecipitates (IPs) were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG and c-Myc. (B) HA-FLAG-FBXL5 was immunoprecipitated from stable Flp-In TREx-293 cells using antibody to HA. WCEs and IPs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG, IRP1, IRP2, and β-tubulin. (C) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with FLAG-IRP2 and Myc-FBXL5, Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box, or empty vector and treated for 8 hours with FAC or DFO. FLAG-IRP2 was immunoprecipitated using antibodies to FLAG. WCEs and IPs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG, c-Myc, and β-tubulin.

To determine whether the FBXL5-IRP2 interaction is regulated by iron, we immunoprecipitated FLAG-IRP2 from HEK293 cells coexpressing either Myc-FBXL5 orMyc-FBXL5-ΔF-box after treatment with ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) or the iron chelator desferrioxamine (DFO). FLAG-IRP2 interacted withMyc-FBXL5 and Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box more strongly in cells treated with FAC as compared with those treated with DFO, suggesting that the interaction is iron-regulated (Fig. 1C). In addition, we found that expression of Myc-FBXL5 but not Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box strongly reduced the abundance of coexpressed IRP2, which is consistent with a role for FBXL5 in promoting IRP2 degradation and FBXL5-ΔF-box acting as a dominant negative mutant. The interaction ofMyc-FBXL5 and Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box with IRP1 and an IRP1-C3S mutant, which is sensitive to iron-dependent degradation because of its inability to form a 4Fe-4S cluster, was also iron-regulated (fig. S3) (18, 19).

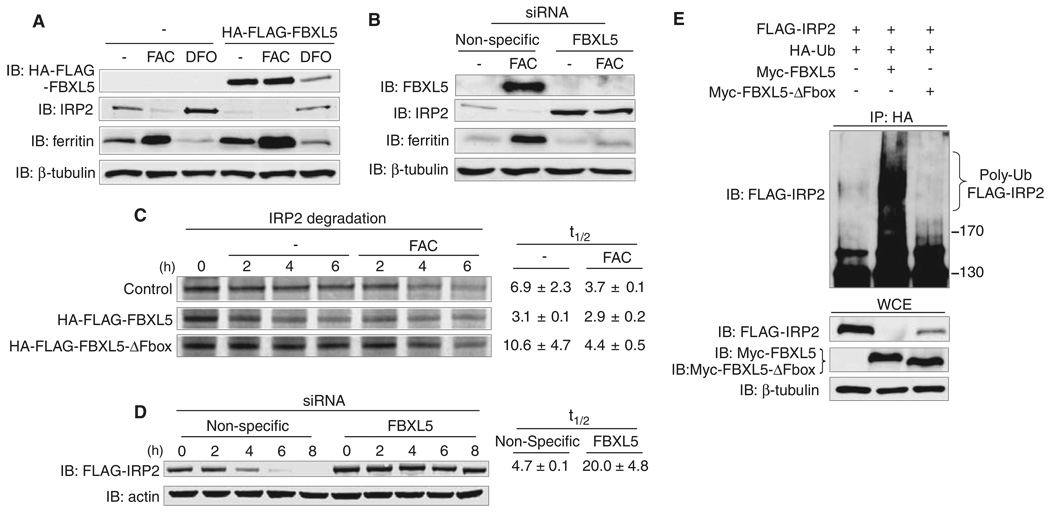

Coimmunoprecipitation analyses showed that FBXL5 overexpression reduced the levels of co-transfected IRP2 in an iron-regulated manner (Fig. 1C). Stable expression of HA-FLAG-FBXL5 in HEK293 cells also reduced endogenous IRP2 levels in an iron-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Reduced IRP2 was associated with an increase in the iron-storage protein ferritin, indicating that ferritin was translationally derepressed (1, 2). FBXL5 depletion by small interfering RNA (siRNA) in HEK293 cells increased IRP2 and decreased ferritin protein levels independently of iron treatment (Fig. 2B). Similar results were found when FBXL5 was depleted from IMR90 human diploid fibroblasts (fig. S4), indicating that IRP2 regulation by FBXL5 is not limited to transformed cells.

Fig. 2.

FBXL5 regulates IRP2 ubiquitination and iron-dependent degradation. (A) Flp-In TREx-293 cells stably expressing HA-FLAG-FBXL5 or control cells were treated for 8 hours with FAC or DFO. WCEs were probed with antibodies to FLAG, IRP2, ferritin, and β-tubulin. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with nonspecific or FBXL5 siRNAs and then treated with or without FAC for 8 hours. WCEs were immunoblotted with the specified antibodies. (C) Flp-In TREx-293 cells stably expressing HA-FLAG-FBXL5 or HA-FLAG-FBXL5-ΔF-box or control cells were pulsed with 35S-met/cys for 1 hour and then chased in medium supplemented with or without additional FAC. 35S-labeled endogenous IRP2 was immunoprecipitated with antibody to IRP2 and half-lives (t 1/2) are shown as average ± SD (n = 2 independent experiments). (D) Flp-In TREx-293 cells stably expressing FLAG-IRP2 were treated with nonspecific or FBXL5 siRNAs, pulsed with doxycycline overnight so as to induce FLAG-IRP2 expression, and then chased in medium supplemented with FAC. WCEs were probed with antibodies to FLAG and actin. FLAG-IRP2 half-lives (t 1/2) are shown as average ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments). (E) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with HA-Ub, FLAG-IRP2 and Myc-FBXL5, Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box, or empty vector and then treated with FAC and MG132 for 4 hours and ubiquitin conjugates immunoprecipitated by using antibodies to HA. HA-immunoprecipitates (IP: HA) and WCEs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG, c-Myc, and β-tubulin.

To determine whether FBXL5 regulates IRP2 iron-dependent degradation, pulse-chase experiments were performed in order to measure the half-life of endogenous IRP2 in control HEK293 cells or cells expressing HA-FLAG-FBXL5 or HA-FLAG-FBXL5-ΔF-box with or without FAC (17). Expression of HA-FLAG-FBXL5 reduced the half-life of IRP2 in both untreated and FAC-treated cells, whereas expression of HA-FLAG-FBXL5-ΔF-box increased IRP2 half-life (Fig. 2C). Depletion of FBXL5 by siRNA inhibited FLAG-IRP2 degradation as compared with that of cells treated with nonspecific siRNA (Fig. 2D). FBXL5 depletion also prevented the iron-dependent degradation of FLAG-IRP1-C3S (fig. S5).

To determine whether FBXL5 catalyzes IRP2 ubiquitination, we analyzed the abundance of IRP2-ubiquitin conjugates after FBXL5 overexpression (17). FLAG-IRP2, HA-ubiquitin (HA-Ub), and Myc-FBXL5 or Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box were coexpressed in HEK293 cells, and Ub-conjugates were immunoprecipitated under denaturing conditions by use of antibodies to HA. Overexpression of Myc-FBXL5, but not Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box, increased FLAG-IRP2 poly-ubiquitination (Fig. 2E). Similarly, Myc-FBXL5, but not Myc-FBXL5-ΔF-box, increased the ubiquitination of FLAG-IRP1 and FLAG-IRP1-C3S (fig. S6).

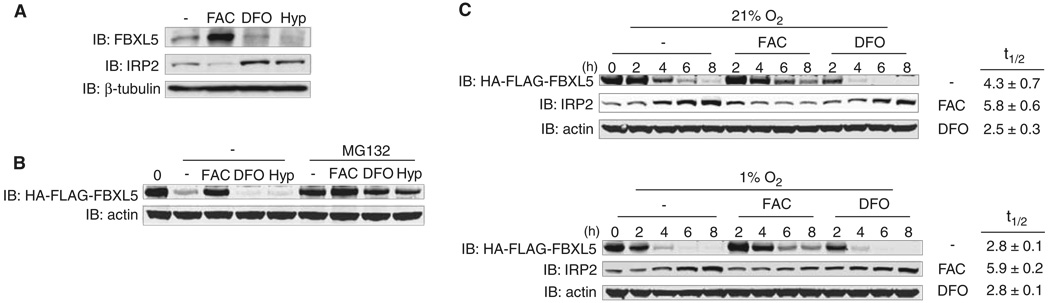

Our data suggest that FBXL5 protein stability may be iron-regulated (Figs. 1C and 3, A and B). We hypothesized that oxygen levels may also affect FBXL5 stability because IRP2 is stabilized during hypoxia (10, 20). We tested these hypotheses by analyzing endogenous FBXL5 levels in cells treated with FAC, DFO, or hypoxia (1% O2). FBXL5 levels increased with FAC and decreased with DFO and hypoxia (Fig. 3A). Reduction of FBXL5 protein by DFO or hypoxia was blocked by treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, suggesting that FBXL5 is targeted for proteasomal degradation under these conditions (Fig. 3B). Pulse-chase experiments at 21% O2 showed that FBXL5 half-lives were increased with FAC treatment (5.8 hours) and decreased by DFO (2.5 hours) as compared with that of untreated cells (4.3 hours) (Fig. 3C). The half-life of HA-FLAG-FBXL5 was also decreased in untreated cells exposed to 1% O2 (Fig. 3C). Thus, FBXL5 stability is dependent on cellular iron and oxygen concentrations.

Fig. 3.

Hypoxia and iron depletion promote the proteasomal degradation of FBXL5. (A) Flp-In TREx-293 control cells were treated with FAC, DFO, or 1% O2 (Hyp) for 8 hours. WCEs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FBXL5, IRP2, and β-tubulin. (B and C) Flp-In TREx-293 cells stably expressing HA-FLAG-FBXL5 were treated overnight with doxycycline so as to induce HA-FLAG-FBXL5 expression and then chased in control medium (−) in 21% O2 or 1% O2 (hypoxia) or in medium supplemented with FAC or DFO. (B) Cells were supplemented with or without MG132 for 6 hours. WCEs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG and actin. (C) WCEs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG, IRP2, and actin. HA-FLAG-FBXL5 half-lives (t 1/2) are shown as average ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments).

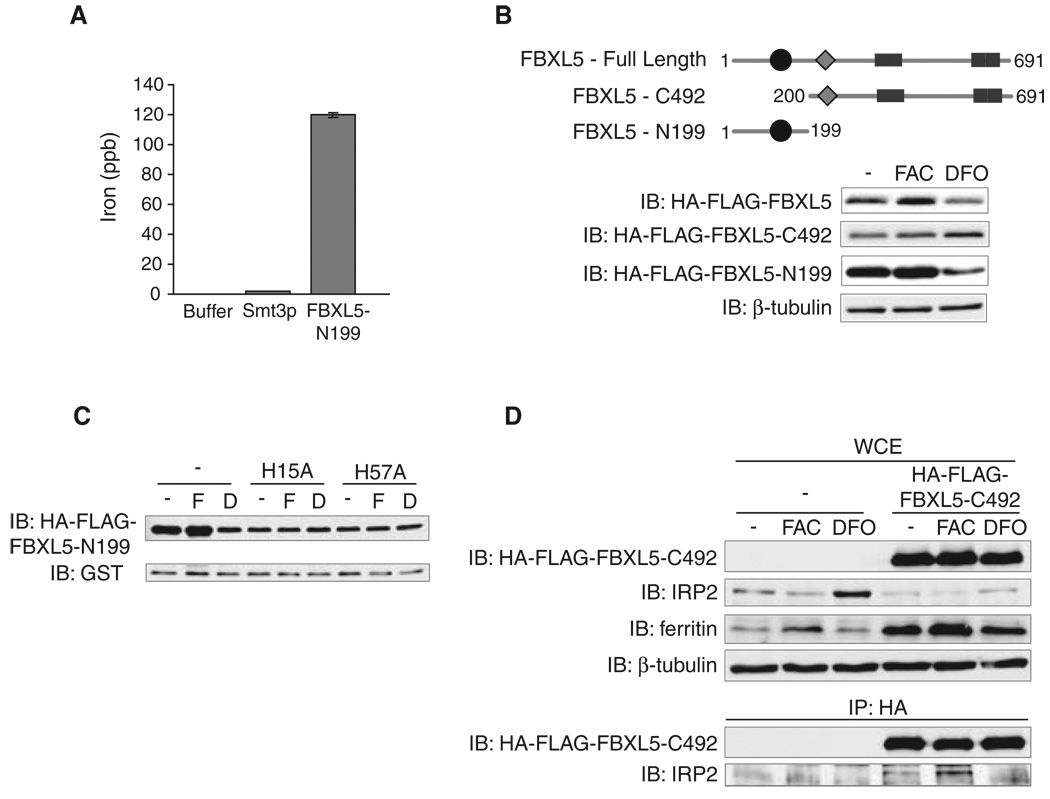

We next examined the role of the putative hemerythrin-like binding domain (PFAM01814) in regulating FBXL5 stability and function. Hemerythrins are oxygen carriers that bind to oxygen through a diiron metal center (21). The hemerythrin-like domain of FBXL5 could therefore function as a cellular iron and oxygen “sensor” by directly binding iron and oxygen. The protein-threading algorithm HHpred (22) revealed that the FBXL5 N terminus is structurally homologous to other hemerythrin family members, with the highest-scoring hit (P = 1.6 × 10−17) belonging to a hemerythrin-like domain protein from Neisseria meningitides (Uniprot, Q9JYL1) (fig. S7). Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis showed that iron copurified with a recombinant fragment of FBXL5 (FBXL5-N199), which encompasses the hemerythrin-like domain, but not buffer alone or His-Smt3p, an unrelated control protein (Fig. 4A) (17). Thus, the N terminus of FBXL5 can function as a hemerythrin domain to coordinate iron and oxygen binding.

Fig. 4.

FBXL5 stability is regulated by an iron-binding hemerythrin-like domain. (A) An N-terminal fragment of FBXL5 encompassing amino acids 1 to 199 (FBXL5-N199) or Smt3p (negative control) was expressed in Escherichia coli, and the amount of copurifying iron was measured by means of ICP-MS. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-FLAG-FBXL5, HA-FLAG-FBXL5-N199, or HA-FLAG-FBXL5-C492 (amino acids 200 to 691) and treated with FAC or DFO for 8 hours. WCEs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG or β-tubulin. (C) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with HA-FLAG-FBXL5-N199, HA-FLAG-FBXL5-N199-H15A, or HA-FLAG-FBXL5-N199-H57A, and a plasmid expressing glutathione S-transferase (GST) as a marker for transfection efficiency, and treated with FAC (F) or DFO (D) for 8 hours. WCEs were immunoblotted with antibodies to FLAG and GST. (D) Flp-In TREx-293 cells stably expressing HA-FLAG-FBXL5-C492 or control cells were treated for 8 hours with FAC or DFO. HA-FLAG-FBXL5-C492 was immunoprecipitated by use of antibodies to HA. WCEs and IPs were probed with antibodies to FLAG, IRP2, ferritin, and β-tubulin.

Based on the FBXL5 domain structure, we hypothesized that the C-terminal 492 amino acids of FBXL5 (FBXL5-C492) containing both the F-box domain and the leucine-rich repeats function in substrate recognition and ubiquitin conjugation, whereas the N-terminal 199 amino acids regulate FBXL5 stability. We expressed the HA-FLAG-FBXL5-N199 and -C492 fragments in HEK293 cells and analyzed their abundance after FAC and DFO treatments (Fig. 4B). HA-FLAG-FBXL5 and HA-FLAG-FBXL5-N199 protein levels were iron-dependent, whereas HA-FLAG-FBXL5-C492 abundance was not iron-regulated. We also found that the mutation of two putative iron-binding residues in the hemerythrin-like domain, H15A and H57A, reduced the abundance and iron-dependent stability of FBXL5 as compared with the wild-type protein (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these data indicate the hemerythrin-like domain regulates FBXL5 stability through iron-coordination.

Because FBXL5-C492 is stable in iron-depleted cells but retains the ability to interact with IRP2, we used this C-terminal fragment to determine whether iron regulates the FBXL5-IRP2 interaction beyond controlling FBXL5 stability. Expression of HA-FLAG-FBXL5-C492 in HEK293 cells reduced endogenous IRP2 levels, indicating that this C-terminal fragment can promote IRP2 degradation (Fig. 4D). IRP2 levels in the HA-FLAG-FBXL5-C492–expressing cells remain partially iron-regulated (stabilized in DFO compared FAC), suggesting that intracellular iron concentrations are still capable of influencing this pathway. Moreover, HA-FLAG-FBXL5-C492 associates with IRP2 more strongly in FAC-treated cells as compared with DFO-treated cells (Fig. 4D). Thus, an iron-dependent mechanism promotes the physical association of FBXL5 with IRP2. By analogy to other F-box proteins in which substrate binding is dependent upon the posttranslational modification of the target, these data could be explained by an iron-regulated modification on IRP2 that stimulates its association with FBXL5.

Our study demonstrates that IRP2 protein levels are controlled by an iron-regulated SKP1-CUL1-FBXL5 complex (fig. S8). In the presence of iron and oxygen, the FBXL5 hemerythrin-like domain binds iron, resulting in the stabilization of a SKP1-CUL1-FBXL5 complex that catalyzes IRP2 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Conversely, loss of iron and/or oxygen binding by the hemerythrin-like domain renders FBXL5 susceptible to proteasomal degradation. These studies identify an iron sensor that functions as a key regulator of iron homeostasis in eukaryotes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1176333/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S8

Table S1

References

References and Notes

- 1.Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Hentze MW. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008;28:197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallander ML, Leibold EA, Eisenstein RS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763:668. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouault TA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:406. doi: 10.1038/nchembio807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo B, Phillips JD, Yu Y, Leibold EA. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:21645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo B, Yu Y, Leibold EA. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:24252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwai K, Klausner RD, Rouault TA. EMBO J. 1995;14:5350. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samaniego F, Chin J, Iwai K, Rouault TA, Klausner RD. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:30904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa H, et al. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamanaka K, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:336. doi: 10.1038/ncb952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson ES, Rawlins ML, Leibold EA. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302798200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:954. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.954-965.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zumbrennen KB, Hanson ES, Leibold EA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardozo T, Pagano M. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:739. doi: 10.1038/nrm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:9. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:242. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolters DA, Washburn MP, Yates JR., 3rd Anal. Chem. 2001;73:5683. doi: 10.1021/ac010617e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 18.Clarke SL, et al. EMBO J. 2006;25:544. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:2423. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01111-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyron-Holtz EG, Ghosh MC, Rouault TA. Science. 2004;306:2087. doi: 10.1126/science.1103786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stenkamp RE. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:715. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.This work was supported by grants from NIH (GM45201 to E.A.L), the Swedish Cancer Society (N.B. and O.S.), the Swedish Children Cancer Foundation (O.S.), the Swedish Research Council (O.S.), the Cancer Society in Stockholm (O.S.), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (A.P. and M.U.), the Stein-Oppenheimer Foundation (J.A.W.), and the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center (J.A.W.). We thank D. Lim for graphic support.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.