Abstract

Background

Circadian rhythm abnormalities are strongly associated with bipolar disorder, however the role of circadian genes in mood regulation is unclear. Previously, we reported that mice with a mutation in the Clock gene (ClockΔ19) display a behavioral profile that is strikingly similar to bipolar patients in the manic state.

Methods

Here, we utilized RNA interference (RNAi) and viral-mediated gene transfer to knock-down Clock expression specifically in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of mice. We then performed a variety of behavioral, molecular and physiological measures.

Results

We found that knock-down of Clock specifically in the VTA results in hyperactivity and a reduction in anxiety-related behavior which is similar to the phenotype of the ClockΔ19 mice. However, VTA specific knock-down also results in a substantial increase in depression-like behavior, creating an overall mixed-manic state. Surprisingly, VTA knock-down of Clock also altered circadian period and amplitude, suggesting a role for Clock in the VTA in the regulation of circadian rhythms. Furthermore, VTA dopaminergic neurons expressing the Clock shRNA have increased activity compared to controls, and this knock-down alters the expression of multiple ion channels and dopamine-related genes in the VTA which could be responsible for the physiological and behavioral changes in these mice.

Conclusions

Taken together, these results suggest an important role for CLOCK in the VTA in the regulation of dopaminergic activity, manic and depressive-like behavior, and circadian rhythms.

Keywords: VTA, Bipolar disorder, Anxiety, Depression, Dopamine, RNAi

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a severe psychiatric illness that is characterized by extreme changes in mood. Several studies have found irregularities in daily rhythms in activity, body temperature, blood pressure, the secretion of different metabolites in urine, and in circulating hormone levels in bipolar patients (1–6). Furthermore, bipolar patients appear to have an unstable and non-adaptive clock, and in fact Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) which maintains patients on a regular sleep and social schedule is very effective in reducing the number of manic and depressive episodes (7). Interestingly, treatment with the mood stabilizer lithium leads to a lengthening of the circadian period that is observed across several species and this effect on rhythms may underlie its therapeutic efficacy (8, 9). In addition, the use of other chronobiological tools such as bright light therapy have proven to be effective for the modulation of both circadian rhythms and mood in bipolar disorder and other affective disorders (4). Thus, it has been hypothesized that abnormalities in the circadian clock contribute to the development and progression of mood disorders, including bipolar disorder.

Circadian rhythms are controlled by a conserved group of core clock genes (10). The proteins, Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Kaput (CLOCK) and Brain and Muscle ARNT-Like Protein 1 (BMAL1) bind to cis-regulatory elements in several genes including the Period genes (Per1, 2 and 3) and the Cryptochrome genes (Cry 1 and 2) (11, 12). The PER and CRY proteins suppress the activity of CLOCK and BMAL1, creating a negative feedback loop which cycles over the course of approximately twenty-four hours (13). The master circadian clock is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), however these genes are widely expressed throughout the brain and in other organs where they can form additional pacemakers which may cycle independently from the SCN.

Previously we found that mice with a mutation in the Clock gene (ClockΔ19) which creates a dominant-negative protein (11, 14), display a complete behavioral profile that is very similar to human mania (15). Furthermore, chronic treatment with lithium restored the majority of their abnormal behaviors to wild type levels. Interestingly, when we recorded from dopamine neurons in the VTA we found that the ClockΔ19 mice have and increase in dopaminergic activity (15, 16). Since the ClockΔ19 animals express the mutant protein throughout the brain and through all stages of development, we wanted to determine the importance of CLOCK in the VTA alone in adult animals. Thus we developed a new strategy to knock-down the expression of CLOCK in the VTA of adult mice using a CLOCK-specific shRNA expressed in adeno-associated virus (AAV).

Materials and Methods

Animals and Housing

8–10 week old male C57BL/6J mice (bred at UT Southwestern) were used for all the studies. Mice were group housed on a 12h light/dark cycle with lights on at 7am and lights off at 7pm with ad lib access to food and water for most studies. For the circadian rhythm studies, mice were singly housed with access to a running wheel and ad lib food and water first in a 12/12 L/D cycle and then they were put into constant darkness to measure free running rhythms. All other behavioral tests were performed at ZT3-6. All mouse experiments were in compliance with protocols approved by our institutional animal care committee.

Construction of the Clock shRNA and AAV purification

Viral production and shRNA design were carried out using a helper-free triple transfection method in HEK 293 cells (ATCC) as described in Hommel et al., 2003 (17) and was purified according to Zolotukhin et al., (18). Sequences and other details are in Supplement 1.

Immunohistochemistry

Staining procedures were carried out as described previously (16). Details on this protocol, antibodies used, and validation of viral infection can be found in Supplement 1.

Behavioral Tests

The locomotor response to novelty, circadian locomotor rhythms, elevated plus maze, open field, dark light, forced swim test and learned helplessness test were all performed as described previously (15,16). Detailed methods can be found in Supplement 1.

Electrophysiology

Recordings were performed as described in Han et. al., 2006 (19). Details can be found in Supplement 1.

Laser Capture microdissection, RNA isolation

Frozen brains from mice infected with AAV scrambled or Clock shRNA were sliced into 7µm sections and placed on slides (Arcturus). Slides were stored at −80°C until further processing on the LCM (Arcturus). LCM slides were dehydrated in 100% ethanol for 20 sec followed by xylene for 20 sec. Slides were then air dried and mounted in the LCM. The transfected regions could be visualized by fluorescent microscopy since all viruses used co-expressed GFP. 3000 transfected cells were laser-captured from the VTA of each mouse. Following sample collection, RNA was purified using the PicoPure RNA extraction kit (MDS Analytical technologies) as described by the manufacturer and processed with the RiboAmp kit (MDS Analytical technologies). One round of RNA amplification was performed before the amplified RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen) and quantified by qPCR (Applied Biosystems).

Quantitative PCR

Real time PCR was performed as described previously (16). Details including primer lists can be found in Supplement 1. The amount of gene expression was quantified using the ΔΔCt method as previously described (20).

Microarray Analysis

Methods and analysis are similar to Wallace et al., 2009 (21). Details can be found in Supplement 1.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Significance for two group comparisons in behavioral assays and qPCR analysis was determined by an independent Student’s T-test. One-way ANOVA was used to determine significance in the period calculation for circadian experiments. Differences in electrophysiology were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. In all experiments P<0.05 is considered significant.

Results

Stereotaxically injected AAV CLOCK shRNA knocks-down the expression levels of Clock in the VTA of mice

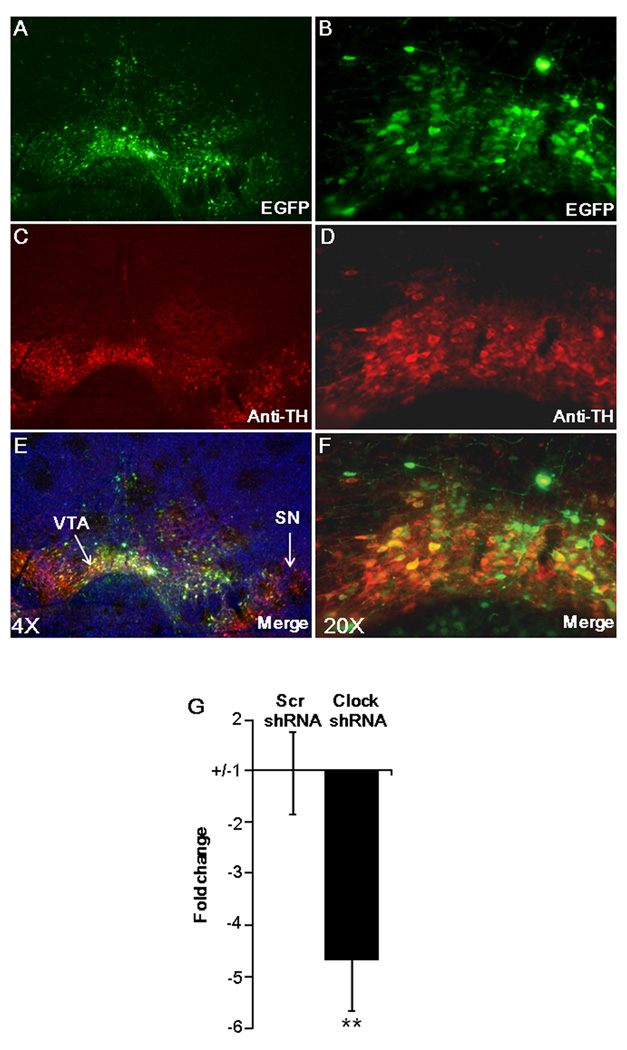

To knock-down the expression of CLOCK in the ventral tegemental area (VTA) of mice, we designed a shRNA sequence that was targeted to a specific region of mouse Clock mRNA (Clock shRNA) and another shRNA containing scrambled sequences (Scr shRNA) with no similarity to any known genes. These shRNAs were cloned into an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector (17) that was designed to express both enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and a U6 promoter-driven shRNA. Use of this vector enabled us to identify only the neurons that express viral-mediated shRNA. To specifically deliver the AAV containing Scr shRNA or Clock shRNA into the VTA of mice, we performed stereotaxic injections. Immunostaining of AAV transfected mouse brain sections with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) showed a clear co-localization of EGFP and TH (Figure 1A–F), demonstrating that we can distinctively target Clock shRNA into the VTA. Two weeks following AAV injection, brains were removed and the cells expressing EGFP were collected using laser capture microscopy (LCM). Quantitative analysis of Clock mRNA levels by real time PCR revealed that Clock shRNA significantly (P< 0.001) reduced the levels of Clock in the VTA of mice when compared to mice injected with the Scr shRNA (Figure 1G). These results demonstrate that the Clock shRNA is able to significantly knock-down the expression of Clock in the VTA of mice. To determine if the knock-down of Clock in the VTA leads to a compensatory increase in expression of Npas2 as is seen in Clock knock-out mice which are missing Clock expression throughout development (22), levels of Npas2 expression were measured in the VTA. In agreement with previous results (23), Npas2 expression was not detectable in either the Scr shRNA injected animals or in the Clock shRNA injected animals in the VTA, while it was readily detectible in striatum and cortical regions, demonstrating that our primer set was functional (data not shown). Thus, there is no measurable compensatory increase in NPAS2 following several weeks of adult knock-down of Clock in VTA.

Figure 1. Adeno-associated viral-mediated expression of Clock shRNA reduces the expression levels of Clock in the VTA of mice.

(A–F) Representative images showing VTA specific targeting of AAV Clock shRNA. AAV-expressing shRNA was injected into the VTA by stereotaxic surgery. Two weeks following surgery, brain sections were immunostained with (A and B) anti-green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and (C–D) anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibodies and images were merged to see colocalization using an epifluorescence microscope. (E–F). (A, C and E) 4× and (B, D and F) are the 20× magnification of the images. (G) Clock shRNA reduces the expression levels of Clock in VTA of mice. Two weeks following AAV-injection, brains were removed and the cells expressing EGFP were collected using laser capture microscopy. Subsequently, RNA was purified from these cells, cDNA was synthesized and subjected to quantitative PCR using Clock-specific primers. RT-PCR showed significant reduction (P< 0.001, n=3, ~3000 cells/mouse) of Clock mRNA levels in Clock shRNA infected VTA.

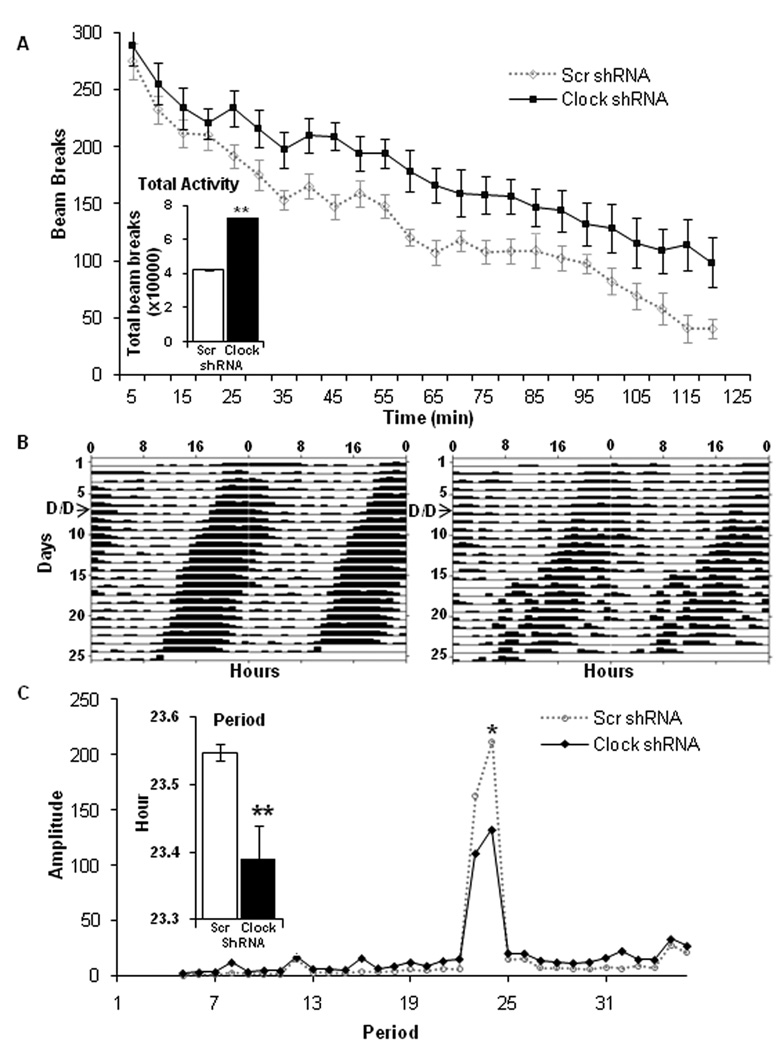

CLOCK knock-down in the VTA leads to a hyperactive response to novelty

After successfully knocking-down Clock expression in the VTA, we wanted to determine how this manipulation would influence behavior. We first determined the effects of Clock knock-down in the VTA on locomotor activity. Clock shRNA injected mice exhibit a significant (P < 0.001) increase in their total locomotor activity in response to a novel environment when compared with Scr shRNA injected mice over a two hour period (Figure 2A and 2A inset). The effect is somewhat delayed, indicating a lack of habituation rather than an immediate hyperactive response to novelty. These results indicate that CLOCK protein expression in the VTA plays a role in regulating locomotor activity over time in response to a novel context.

Figure 2. CLOCK function in the VTA regulates the locomotor response to novelty and circadian locomotor rhythms.

(A) Clock knock-down in the VTA leads to a hyperactive response to novelty. Total locomotor movements of AAV injected mice were continuously measured in a novel environment and the data were collected in 5-min blocks over a period of two hours. The inset shows the total number of beam breaks in a novel environment made by AAV injected mice during a two hour measurement. AAV Clock shRNA injected mice showed significantly greater levels of locomotor activity (p< 0.001, n=15–20). (B) Expression of CLOCK in the VTA plays a critical role in the generation of normal circadian rhythms. Representative actograms showing running wheel activity of Clock (right panel) and Scr (left panel) shRNA infected mice. Mice were maintained under a 12 hr light/dark (L/D) cycle for one week. Subsequently, they were placed in 24 hour constant darkness (D/D) and the wheel running activity data was collected for an additional 15 days. The switch to D/D is noted on the actograms by an arrow. (C) CLOCK knock-down in VTA alters both period and amplitude. Free running period and amplitude were calculated based on wheel running data in the D/D phase. The inset shows the difference in circadian period between the Scr and Clock shRNA injected mice (P<0.01) while the line graph shows the difference in amplitude between Scr and Clock shRNA mice (P<0.01, n=10).

CLOCK knock-down in the VTA leads to abnormal circadian rhythms

To further determine whether suppression of Clock expression in the VTA leads to any alterations in locomotor activity or rhythms in activity, wheel running activity was monitored for an initial seven days under a 12 hour light/dark cycle and then under constant darkness for another 15 days. Amplitude and period were calculated from the dark/dark phase of the wheel running data. Figure 2B shows that the Clock shRNA injected mice display a behavioral rhythmicity throughout the 15 day dark/dark treatment. However, the Clock shRNA injected mice show an increase in their activity levels during the resting phase and less robust activity during the dark phase, indicating a lower rhythm amplitude (P<0.01) (Figure 2C). Interestingly, although Clock shRNA injected mice exhibit an increase in their locomotor activity in a novel environment (Figure 2A), when we examine the total activity in the home cage over 24 hours, the Clock shRNA injected mice display a significant (P<0.05) decrease in total activity (data not shown). Furthermore, Clock shRNA injected mice show a significant decrease (p<0.01) in the circadian period that was on average 15 min shorter (23.4 ± 0.05 hr) than the Scr shRNA injected mice which display a normal circadian period of 23.6 ± 0.01 hr (Figure 2C, inset). Together, these data suggest that expression of CLOCK protein in the VTA might play a critical role in the generation of normal circadian rhythms in locomotor activity.

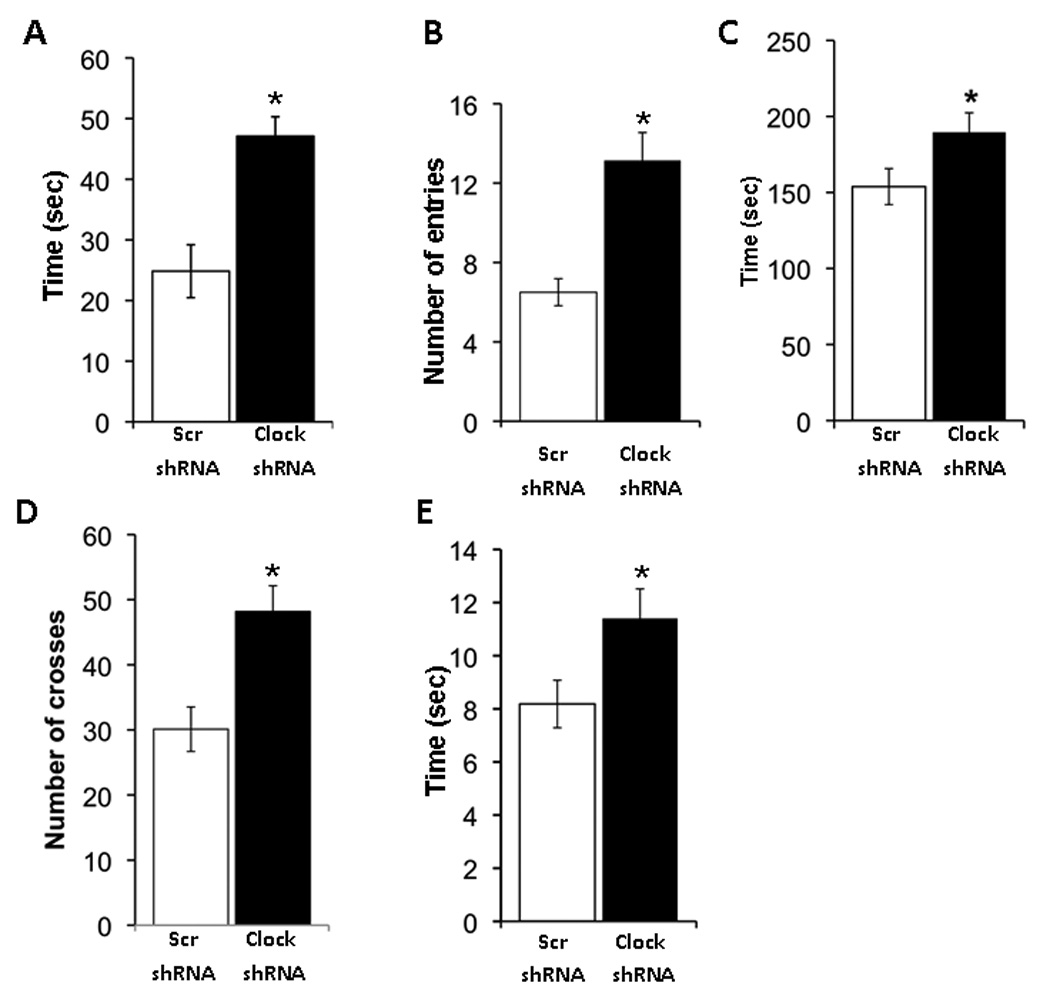

CLOCK knock-down in the VTA leads to less anxiety-related behavior

To examine the contribution of Clock expression in the VTA to anxiety-related behavior, we subjected Clock and Scr shRNA injected mice to three separate measures: the elevated plus maze, light/dark box, and the open-field. Previous studies have validated these tests as measures of anxiety since behavior is significantly altered in wild type mice with the administration of anxiolytic and anxiogenic drugs (24). Furthermore, results from our lab and others show a clear separation of anxiety-related behavior from hyperactivity in these tests (15, 21). Although the Clock shRNA injected mice have an increase in activity over a two hour period in a novel environment, they are similar to control mice in response to this environment for the first 25 minutes (Figure 2A). Since anxiety-related measures are performed over 5–10 minute periods, the failure to habituate to novelty by the Clock shRNA injected mice should not influence these paradigms. In the elevated plus-maze we find that the Clock shRNA injected mice spend significantly more time (47.0 +/− 7.07 sec vs 23.8 +/− 7.16, P<0.05) on the open arm than the Scr shRNA injected mice. In addition, we find that the number of entries made by the Clock shRNA injected mice in the open arm are significantly higher as compared with Scr shRNA injected mice (13.1+/−1.4 vs 6.5 +/− 0.7, p<0.001; Figure 3A–B). Furthermore, in the light/dark test we find that the mice injected with the Clock shRNA not only spend significantly more time (189.6 +/−12.8, P<0.05) in the lighted area of the box (153.8 +/−11.8), but they also made significantly increased number of crosses to the lighted area (48.2+/−4.0 vs 30.1+/−3.4, p<0.001; Figure 3C–D). In the open field Clock shRNA injected mice spend significantly more time (11.4+/−1.1, P<0.05) in the center of the field than the scr shRNA injected mice (8.2+/−0.9 sec; Figure 3E). The results obtained with these three separate measures are consistent with each other and suggest that knock-down of Clock in the VTA leads to an overall reduction in anxiety-related behavior.

Figure 3. CLOCK in the VTA is important for the control of anxiety-related behavior.

(A–B) Clock knock-down in mice leads to less anxiety. AAV infected mice were subjected to the elevated plus maze test. The time spent on the closed and open arms, as well as the number of explorations of open and closed arms were determined by video tracking software. Clock shRNA injected mice spent significantly more time in the open arm and had more entries into the open arm as compared to the Scr shRNA injected mice (n= 10–15, p< 0.05). (C–D) AAV infected mice were subjected to the dark/light test and number of crosses into the light and the time spent on the light side was measured. Clock shRNA injected mice spend more time in the light and had more crosses into the light side as compared with Scr shRNA injected mice (n= 10–20, p< 0.05). (E) AAV infected mice were subjected to the open field test and the time spent at the periphery and in the center was calculated by video tracking software. Clock shRNA injected mice spend more time in the center of the arena than the Scr shRNA injected mice (n=10–20, p<0.05).

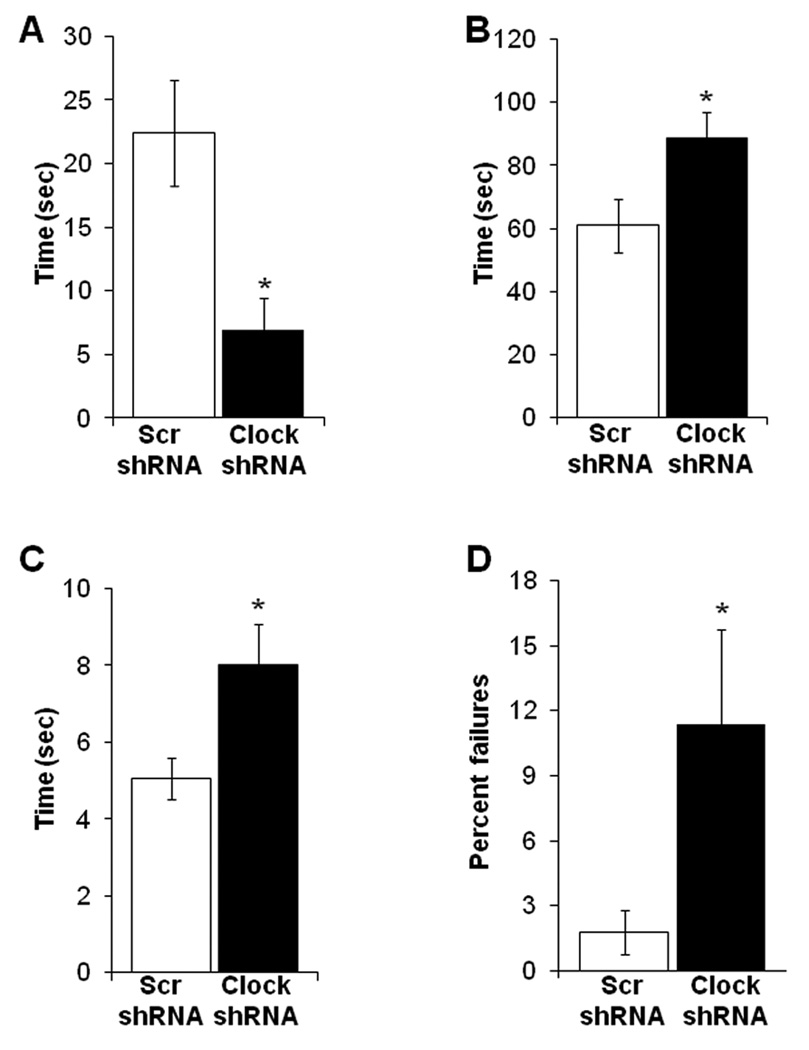

CLOCK knock-down in the VTA leads to increased depression-like behavior

To determine whether knock-down of Clock mRNA expression in the VTA of mice alters depression-like behavior, we carried out forced swim (FST) and learned helplessness tests (LH). These measures have been validated extensively with antidepressant drugs (25, 26). Immobility in the FST and failure to escape in the LH test are indicative of depression-like behavior. Surprisingly, when the latency to immobility is measured in the FST, we find that Clock shRNA injected mice display significantly (P<0.01) shorter latency to immobility compared to Scr shRNA injected mice (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the total immobility period (81 +/− 8.2 sec) is significantly (P<0.05) longer in the Clock shRNA injected mice (Figure 4B). To further substantiate the results obtained with the FST, we carried out the LH test. We find that the Clock shRNA injected mice exhibit greater latency to escape in the LH test (Figure 4C) when compared to the Scr shRNA injected mice (8.0 +/− 1.06 vs 5.0 +/− 0.5 sec, P<0.05). Moreover, the percentage of failures to escape is significantly higher in Clock shRNA injected mice than in Scr shRNA controls (Figure 4C). These results are the opposite of those seen in the ClockΔ19 mice which display a decrease in depression-related behavior in both of these measures (Roybal et al., 2007). Thus, these tests show that CLOCK function in the VTA is necessary for proper mood-related behavior, however different manipulations of this protein lead to opposite effects.

Figure 4. CLOCK in the VTA regulates depression-like behavior.

Clock knock-down results in an increase in depression-like behavior. (A) AAV infected mice were subjected to the forced swim test (FST). Latency to immobility was determined when the first cessation of all movements for 3 seconds occurs. Clock shRNA injected mice displayed significantly less latency to immobility (n=10–20, p<0.05). (B) Total immobility in the FST was measured and AAV infected mice spend significantly more time immobile (n= 10–20, p< 0.05). (C) AAV infected mice were subjected to the learned helplessness paradigm. Clock shRNA injected mice showed significantly longer latency to escape (n= 10–20, p< 0.05). (D) Clock shRNA injected mice showed a significantly greater percentage of failures to escape (n=10–20, p<0.05).

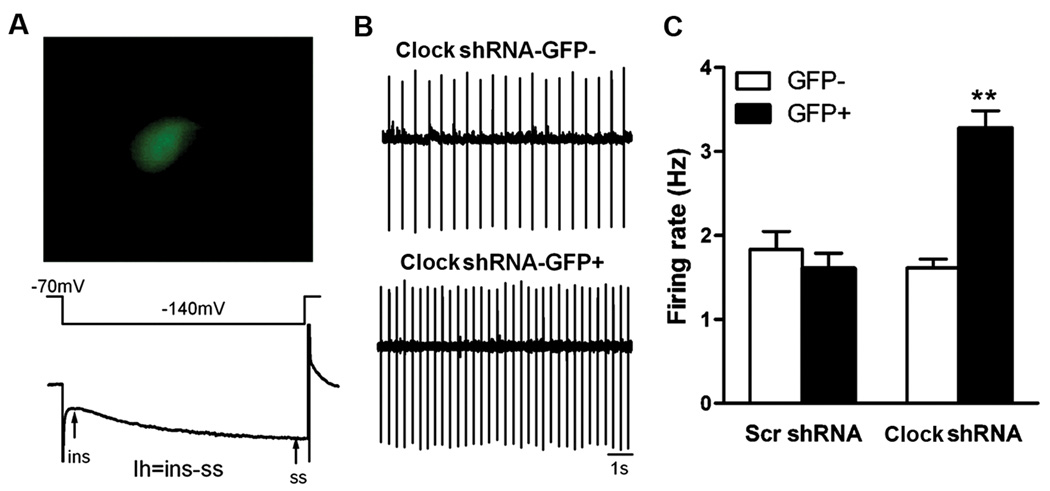

Dopaminergic cell firing is enhanced with CLOCK knock-down

Previously we found that the ClockΔ19 mice have an increase in dopaminergic cell firing which accompanies their overall manic-like phenotype (16). To determine how knock-down of Clock mRNA expression in the VTA of adult animals influences dopaminergic cell firing, we recorded the firing rate of individual dopamine neurons in the VTA from mice that were injected with the Scr or Clock shRNA. In both sets of animals we also recorded from neighboring dopaminergic cells that were not infected with a virus as a control. We find that Clock shRNA infected cells have a significant increase (P<0.01) in the firing rate of dopaminergic cells compared to both non infected cells and the AAV Scr shRNA infected cells (Figure 5). These results, together with the behavioral abnormalities seen in the Clock shRNA injected mice, strongly suggest that CLOCK is involved in modulating dopaminergic activity, and that this modulation is important in regulating mood, activity and anxiety-related behavior.

Figure 5. CLOCK in the VTA regulates dopaminergic cell firing.

Knock-down of Clock expression with AAV Clock shRNA increases the excitability of VTA dopamine neurons in mice. (A) An example of a VTA neuron expressing virally encoded GFP (top). Dopamine neurons elicit a slowly developing inward current (Ih) by a hyperpolarizing voltage step from −70 mV to −140 mV. Ih was calculated by subtracting the instantaneous current (ins) from the steady-state current (ss) (bottom). (B,C) A significant increase of firing rate in dopamine neurons is observed in the Clock shRNA-GFP+ group (n=43 cells), but not in the Clock shRNA-GFP− (n=33 cells) or the Scr shRNA-GFP+ group (n=22 cells) (representative traces shown in B). **P<0.01 compared to Clock shRNA-GFP− or Scr shRNA-GFP+.

Knock-down of CLOCK in the VTA leads to changes in gene expression

Since CLOCK is a transcription factor, we wanted to know what gene expression changes would occur following Clock knock-down in the VTA. We performed microarray analysis on RNA isolated from VTA tissue of Clock shRNA infected mice and scrambled controls. We find a number of changes that occur with Clock knock-down in the VTA (see Table S1 and Figure S1 in Supplement 1). 90% of the selected genes that we chose for RT/PCR confirmation (total of 12 genes selected) showed similar changes in expression, giving us great confidence in our microarray data (see Table S2 in Supplement 1 for genes). Interestingly, we noticed that the expression levels of a number of ion channels are altered following Clock shRNA infection (Table 1). Most of the channels were upregulated and there are a number of cholinergic channels and glutamatergic channels that show this regulation. An upregulation of these channels could lead to increased dopaminergic activity in the VTA. Fewer channels were downregulated and they included some potassium channels. We also found changes in a number of genes that are known to regulate dopaminergic activity (Table 2).

Table1.

Channels and associated proteins regulated in the VTA with Clock knock-down via shRNA

| Fold | change | Symbol | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.57 | Up | Chrna3 | cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 3 |

| 2.33 | Up | Gabra4 | gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA-A) receptor, subunit alpha 4 |

| 2.31 | Up | Trpc6 | transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 6 |

| 2.05 | Up | Chrna6 | cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 6 |

| 1.84 | Up | Cacng5 | calcium channel, voltage-dependent, gamma subunit 5 |

| 1.79 | Up | Grm2 | glutamate receptor, metabotropic 2 |

| 1.71 | Up | Chrnb4 | cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, beta polypeptide 4 |

| 1.64 | Up | Grik3 | glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 3 |

| 1.62 | Up | Scn3a | sodium channel, voltage-gated, type III, alpha |

| 1.62 | Up | Kcnip2 | Kv channel-interacting protein 2 |

| 1.61 | Up | Homer2 | homer homolog 2 (Drosophila) |

| 1.58 | Up | Ryr1 | ryanodine receptor 1, skeletal muscle |

| 1.56 | Up | Glra2 | glycine receptor, alpha 2 subunit |

| 1.54 | Up | Gabra2 | gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA-A) receptor, subunit alpha 2 |

| 1.52 | Up | Kcnd3 | potassium voltage-gated channel, Shal- related family, member 3 |

| 1.52 | Up | Kcnip4 | Kv channel interacting protein 4 |

| 1.50 | Up | Kcnk2 | potassium channel, subfamily K, member 2 |

| 1.44 | Up | Trpv1 | transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 1 |

| 1.43 | Up | Kcna5 | potassium voltage-gated channel, shaker- related subfamily, member 5 |

| 1.42 | Up | Gria2 | glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA2 alpha 2) |

| 1.41 | Up | Grip2 | glutamate receptor interacting protein 2 |

| 1.38 | Up | Scn2a1 | sodium channel, voltage-gated, type II, alpha 1 |

| 1.37 | Up | Cacnb3 | calcium channel, voltage-dependent, beta 3 subunit |

| 1.36 | Up | Kcnmb4 | potassium large conductance calcium- activated channel, subfamily M, beta member 4 |

| 1.67 | Down | Grin2b | glutamate receptor,ionotropic, NMDA2B (epsilon 2) |

| 1.60 | Down | Hcn1 | hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated K+ 1 |

| 1.46 | Down | Kcng1 | potassium voltage-gated channel,subfamily G, member 1 |

| 1.43 | Down | Kcnc1 | potassium voltage gated channel, Shaw- related subfamily, member 1 |

| 1.39 | Down | Kcnj5 | potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 5 |

Table2.

Genes involved in dopamine synthesis, regulation or metabolism that are regulated following Clock knock-down in the VTA

| Fold | Change | Symbol | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.44 | Up | Nos1 | nitric oxide synthase 1, neuronal |

| 2.36 | Up | Ntrk1 | neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 1 |

| 2.13 | Up | Tacr3 | tachykinin receptor 3 |

| 2.04 | Up | Drd2 | dopamine receptor 2 |

| 2.03 | Up | Th | tyrosine hydroxylase |

| 2.04 | Up | Ntf3 | neurotrophin 3 |

| 1.77 | Up | Snca | synuclein, alpha |

| 1.77 | Up | Slc1a3 | solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 |

| 1.73 | Up | Cckar | cholecystokinin A receptor |

| 1.66 | Up | Ddc | dopa decarboxylase |

| 1.36 | Up | Sncaip | synuclein, alpha interacting protein (synphilin) |

| 8.88 | Down | Cartpt | CART prepropeptide |

| 8.30 | Down | Dbh | dopamine beta hydroxylase |

| 1.59 | Down | Penk1 | preproenkephalin 1 |

| 1.38 | Down | Adcy9 | adenylate cyclase 9 |

| 1.37 | Down | Htr4 | 5 hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 4 |

Discussion

These studies indicate that expression of CLOCK in the adult ventral tegmental area (VTA) is involved in the modulation of mood, anxiety and locomotor behavior in mice. The adeno-associated virus (AAV) Clock short hairpin RNA (shRNA) infected animals show a prolonged hyperactive response to novelty and decrease in anxiety-related behavior that is similar to the ClockΔ19 animals. Furthermore, our previous studies found that restoration of a functional CLOCK protein specifically in the VTA of ClockΔ19 mice is sufficient to rescue their hyperactivity and anxiety-related behavior (15). Therefore, it seems clear that the response to novelty and anxiety-related behaviors are largely VTA driven, and that less activity of CLOCK in this region, regardless of the method used or duration of knock-down, results in an increased response to novelty and lowered levels of anxiety-related behavior.

Surprisingly, we find that shRNA-mediated knock-down of CLOCK in the VTA leads to increased levels of depression-like behavior, while the ClockΔ19 animals have a decrease in depression-like behavior (15). Interestingly, when we attempt to rescue the lowered depression-like behavior in ClockΔ19 mice by expressing a functional CLOCK protein in the VTA, we find that it is not sufficient to reverse the behavior (unpublished observations) while it does reverse the anxiety-related phenotypes (15). Depression and anxiety are often co-morbid, however studies are beginning to differentiate specific molecular mechanisms that control each state. For example, a recent study by Wallace et al., (2009) found that rats kept in social isolation developed both increased anxiety and increased depression-like behavior, and both were reversed by chronic antidepressant treatment (21). However, the anxiety-related behaviors and their reversal by antidepressants, were dependent upon expression of the transcription factor, CREB, in the nucleus accumbens shell, while the depression-like behavior was not controlled by a CREB-dependent mechanism (21). Furthermore, anxiety-related behavioral measures in mice may be a reflection of “risk taking” behavior, rather than feelings of anxiety. Patients with bipolar disorder, for example, can feel anxious about certain social or other situations while at the same time they engage in extremely risky behavior without concern about the consequences. Thus, there is a complex interaction between anxiety-related behavior and depression that warrants future study.

These differences in depression-like behavior observed in the ClockΔ19 mice and the Clock shRNA injected mice could come from the fact that the ClockΔ19 animals have the mutation throughout the brain while the Clock shRNA is injected locally in the VTA. It is possible that CLOCK function in another brain region is involved in regulating depression-like behavior. Some possibilities might include the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex since both have been implicated in mood regulation in previous studies (27, 28). There is also the possibility that CLOCK expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is involved in this modulation of behavior.

There are other important differences between this local knock-down and the ClockΔ19 animals that might contribute to the opposing results in measures of depression-like behavior. First, the ClockΔ19 mice have a mutation in the protein which leads to dominant-negative activity while the shRNA affects Clock mRNA expression only. The dominant-negative protein not only affects CLOCK activity, but also likely alters the activity of any protein that interacts with BMAL1. Indeed there are behavioral differences in mice with the ClockΔ19 mutation versus mice which are null for the Clock gene. Clock knock-out animals have essentially normal circadian locomotor rhythms with only a slight alteration in their response to light while the ClockΔ19 animals have extremely long periods or are totally arrhythmic (11, 29). It will be interesting to determine in future studies how overexpression of the CLOCKΔ19 protein specifically in the VTA of adult animals affects depression-related behavior.

The other major difference between the two systems is that the ClockΔ19 mutation is expressed throughout development while the Clock shRNA is injected into adult animals. It is plausible that having this mutation throughout development leads to compensatory effects that alter the adult animal’s behavioral response. Indeed when CLOCK is absent throughout development, NPAS2 expression in the SCN becomes elevated and it can compensate for the loss of CLOCK to control circadian rhythms (22).

Dopaminergic Activity and the Regulation by CLOCK

Interestingly, CLOCK knockdown in the VTA leads to an increase in the firing rate of dopaminergic neurons. These results are similar to the increased dopaminergic cell firing rate observed in ClockΔ19 mice (16). Increased dopaminergic cell firing has long been associated with hyperactive behavior and the reward value for pleasurable stimuli, however other studies find that stress also leads to increased dopamine release (30). Furthermore, a study by Krishnan et al., (2007) found that mice which developed depression-like behavior following chronic social defeat have an increase in dopamine cell firing while mice that are resistant have no change in dopaminergic activity (31). These studies, along with our current study, show that both manic-like and depressive-like behavior is associated with an increase in VTA dopamine cell firing. This could be an important mechanism that underlies bipolar disorder since patients show both mood states, however future studies are needed to determine how this increased firing is involved in mood regulation.

Since CLOCK is a transcription factor, any change in CLOCK expression or activity will influence the expression of many other genes. Using microarray analysis, our previous studies found that there are many differences in gene expression in the VTA of ClockΔ19 mice versus wild type controls including a number of genes that are known to regulate dopaminergic activity (16). We find a similar increase in levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (Th) in the Clock shRNA expressing cells as seen in the ClockΔ19 mice, as well as other interesting changes in genes involved in dopamine synthesis, metabolism and release. Some of these changes may be involved in a common mechanism leading to increased dopaminergic activity in both models, while some of the changes point to different mechanisms that may underlie the differences in depression-related behavior (32). Interestingly, we find differences in expression in a number of ion channels and receptors following VTA specific knock-down of Clock, specifically increases in cholinergic and glutamatergic receptors. The nicotinic acetylcholine (nACh) receptors expressed on cell bodies of dopamine neurons modulate the rate of action potential firing and subsequently levels of dopamine release at synapses (33). Stronger nACh receptor responses make VTA dopaminergic neurons more excitable (34, 35). Interestingly, there was an upregulation of certain GABAergic receptors in the VTA which could be compensatory. Future studies will determine the importance of these changes in receptor and ion channel expression in the increased dopaminergic activity and behavioral changes in these mice.

Circadian Rhythms

Another intriguing finding of this study is that CLOCK knock-down in the VTA alters circadian locomotor rhythms. VTA knock-down leads to a slightly shorter period and a decrease in amplitude. Consistent with our findings, the circadian period of homozygous Clock null mice are on average ~20 min shorter than the wild type mice (29). In contrast, the ClockΔ19 mice also have a decrease in rhythm amplitude but they often display a long period in constant darkness or completely arrhythmic behavior (14). It is uncertain as to how changes in the VTA modulate circadian period. It is also currently unclear as to how changes in circadian rhythms per se contribute to mood related phenotypes, but it is interesting that Clock knock-down in the VTA and ClockΔ19 mice have opposite changes in period length. Interestingly, chronic social defeat is also associated with a reduction in circadian amplitude of body temperature rhythms only in mice that show a depression-like phenotype, suggesting that these rhythm changes may be important in mood regulation (31).

In summary, our results find a significant role for CLOCK in the VTA in the regulation of depression-like and manic-like behavior. Both of these phenotypes are associated with increased dopaminergic activity in this region. While the hyperactivity and anxiety-related behaviors are mostly controlled through CLOCK expression in the VTA, it is likely that other brain regions contribute to the regulation of depression-like behavior. CLOCK in the VTA also regulates some aspects of circadian locomotor activity. These results are important in developing our understanding of the complexities of bipolar disorder, and how multiple mood states might develop with mutation in a single gene.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Mary Kay Lobo for help with the LCM and Scott Russo for the help with viral surgeries. We would also like to thank Drs. Caroline H. Ko and Ming-hu Han for valuable discussion. This work is supported by grants from NIDA the NIMH, NINDS, NARSAD, The McKnight Foundation, and the Blue Gator Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Dr. McClung is a consultant for Orphagen Pharmaceuticals, has received honorarium from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, and has research funding from GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Goetze U, Tolle R. Circadian rhythm of free urinary cortisol, temperature and heart rate in endogenous depressives and under antidepressant therapy. Neuropsychobiology. 1987;18:175–184. doi: 10.1159/000118414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshauer D, Grof E, Alda M, Grof P. Patterns of DST positivity in remitted affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvatore P, Tohen M, Khalsa HM, Baethge C, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ. Longitudinal research on bipolar disorders. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2007;16:109–117. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00004711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClung CA. Circadian genes, rhythms and the biology of mood disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;114:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souetre E, Salvati E, Wehr TA, Sack DA, Krebs B, Darcourt G. Twenty-four-hour profiles of body temperature and plasma TSH in bipolar patients during depression and during remission and in normal control subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1133–1137. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunney JN, Potkin SG. Circadian abnormalities, molecular clock genes and chronobiological treatments in depression. Br Med Bull. 2008;86:23–32. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank E, Swartz HA, Kupfer DJ. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: managing the chaos of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:593–604. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klemfuss H. Rhythms and the pharmacology of lithium. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;56:53–78. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kripke DF, Mullaney DJ, Atkinson M, Wolf S. Circadian rhythm disorders in manic-depressives. Biol Psychiatry. 1978;13:335–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko CH, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 2):R271–R277. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King DP, Zhao Y, Sangoram AM, Wilsbacher LD, Tanaka M, Antoch MP, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian clock gene. Cell. 1997;89:641–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gekakis N, Staknis D, Nguyen HB, Davis FC, Wilsbacher LD, King DP, et al. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science. 1998;280:1564–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siepka SM, Yoo SH, Park J, Lee C, Takahashi JS. Genetics and neurobiology of circadian clocks in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007;72:251–259. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitaterna MH, King DP, Chang AM, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, McDonald JD, et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719–725. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roybal K, Theobold D, Graham A, DiNieri JA, Russo SJ, Krishnan V, et al. Mania-like behavior induced by disruption of CLOCK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6406–6411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClung CA, Sidiropoulou K, Vitaterna M, Takahashi JS, White FJ, Cooper DC, et al. Regulation of dopaminergic transmission and cocaine reward by the Clock gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9377–9381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503584102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hommel JD, Sears RM, Georgescu D, Simmons DL, DiLeone RJ. Local gene knockdown in the brain using viral-mediated RNA interference. Nat Med. 2003;9:1539–1544. doi: 10.1038/nm964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zolotukhin S, Byrne BJ, Mason E, Zolotukhin I, Potter M, Chesnut K, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 1999;6:973–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han MH, Bolanos CA, Green TA, Olson VG, Neve RL, Liu RJ, et al. Role of cAMP response element-binding protein in the rat locus ceruleus: regulation of neuronal activity and opiate withdrawal behaviors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4624–4629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4701-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaPlant Q, Chakravarty S, Vialou V, Mukherjee S, Koo JW, Kalahasti G, et al. Role of nuclear factor kappaB in ovarian hormone-mediated stress hypersensitivity in female mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:874–880. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace DL, Han MH, Graham DL, Green TA, Vialou V, Iniguez SD, et al. CREB regulation of nucleus accumbens excitability mediates social isolation-induced behavioral deficits. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:200–209. doi: 10.1038/nn.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeBruyne JP, Weaver DR, Reppert SM. CLOCK and NPAS2 have overlapping roles in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:543–545. doi: 10.1038/nn1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia JA, Zhang D, Estill SJ, Michnoff C, Rutter J, Reick M, et al. Impaired cued and contextual memory in NPAS2-deficient mice. Science. 2000;288:2226–2230. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilfoil T, Michel A, Montgomery D, Whiting RL. Effects of anxiolytic and anxiogenic drugs on exploratory activity in a simple model of anxiety in mice. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28:901–905. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petit-Demouliere B, Chenu F, Bourin M. Forced swimming test in mice: a review of antidepressant activity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;177:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin P, Massol J, Scalbert E, Puech AJ. Involvement of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in reversal of helpless behavior evoked by perindopril in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;187:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90003-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dranovsky A, Hen R. Hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation by stress and antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1136–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debruyne JP, Noton E, Lambert CM, Maywood ES, Weaver DR, Reppert SM. A clock shock: mouse CLOCK is not required for circadian oscillator function. Neuron. 2006;50:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasar E, Harro J, Lang A, Pold A, Soosaar A. Differential involvement of CCK-A and CCK-B receptors in the regulation of locomotor activity in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;105:393–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02244435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mameli-Engvall M, Evrard A, Pons S, Maskos U, Svensson TH, Changeux JP, et al. Hierarchical control of dopamine neuron-firing patterns by nicotinic receptors. Neuron. 2006;50:911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Laterodorsal tegmental projections to identified cell populations in the rat ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:217–235. doi: 10.1002/cne.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omelchenko N, Sesack SR. Cholinergic axons in the rat ventral tegmental area synapse preferentially onto mesoaccumbens dopamine neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:863–875. doi: 10.1002/cne.20852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.