Abstract

We expressed rat Nav1.6 sodium channels in combination with the rat β1 and β2 auxiliary subunits in Xenopus laevis oocytes and evaluated the effects of the pyrethroid insecticides S-bioallethrin, deltamethrin and tefluthrin on expressed sodium currents using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique. S-Bioallethrin, a Type I structure, produced transient modification evident in the induction of rapidly-decaying sodium tail currents, weak resting modification (5.7% modification at 100 μM), and no further enhancement of modification upon repetitive activation by high-frequency trains of depolarizing pulses. By contrast deltamethrin, a Type II structure, produced sodium tail currents that were ~9-fold more persistent than those caused by S-bioallethrin, barely detectable resting modification (2.5% modification at 100 μM), and 3.7-fold enhancement of modification upon repetitive activation. Tefluthrin, a Type I structure with high mammalian toxicity, exhibited properties intermediate between S-bioallethrin and deltamethrin: intermediate tail current decay kinetics, much greater resting modification (14.1% at 100 μM), and 2.8-fold enhancement of resting modification upon repetitive activation. Comparison of concentration–effect data showed that repetitive depolarization increased the potency of tefluthrin ~15-fold and that tefluthrin was ~10-fold more potent than deltamethrin as a use-dependent modifier of Nav1.6 sodium channels. Concentration–effect data from parallel experiments with the rat Nav1.2 sodium channel co-expressed with the rat β1 and β2 subunits in oocytes showed that the Nav1.6 isoform was at least 15-fold more sensitive to tefluthrin and deltamethrin than the Nav1.2 isoform. These results implicate sodium channels containing the Nav1.6 isoform as potential targets for the central neurotoxic effects of pyrethroids.

Keywords: voltage-gated sodium channel, Nav1.6 isoform, pyrethroid, S-bioallethrin, deltamethrin, tefluthrin

Introduction

Since the discovery and commercial development of photostabilized pyrethroids in the 1970s, these insecticides have been used extensively in agriculture, animal health, home and garden pest control, and the control of insect vectors of human disease (Elliott, 1995). Pyrethroids are commonly regarded as relatively safe insecticides, particularly in comparison with many organophosphorus compounds. However, the acute toxicity of insecticidal pyrethroids to mammals varies widely with structure; the acute oral LD50 values to rats of commercially-used pyrethroids range from 22 mg/kg to >5000 mg/kg (Soderlund et al., 2002). Pyrethroids have been classified into two groups on the basis of their chemical structures and their production of one of two distinct syndromes of acute intoxication. Natural pyrethrins and a structurally heterogeneous group of synthetic pyrethroids (Type I compounds) were characterized by the induction of a whole body tremor (T syndrome), whereas pyrethroids that contain the α-cyano-3-phenoxybenzyl alcohol moiety (Type II compounds) produced sinuous writhing convulsions (choreoathetosis) accompanied by salivation (CS syndrome) (Verschoyle and Aldridge, 1980; Lawrence and Casida, 1982).

Voltage-sensitive sodium channels are the sites of insecticidal action of pyrethroids (Bloomquist, 1993a; Soderlund, 1995) and are also widely regarded as the principal sites of neurotoxic action in mammals (Bloomquist, 1993b; Narahashi, 1996; Soderlund et al., 2002). Sodium channels in the mammalian CNS exist as heterotrimeric complexes of an α subunit and two auxiliary β subunits. The large α subunit forms the ion pore and confers most of the functional and pharmacological properties of voltage-sensitive sodium channels (Catterall, 2000; Goldin, 2001). Mammalian genomes contain nine sodium channel α subunit cDNA sequences (designated Nav1.1 – Nav1.9) that encode sodium-selective, voltage-gated ion channels (Goldin et al., 2000). Four of these α subunit isoforms (Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.3 and Nav1.6) are expressed in the CNS (Goldin, 2001). There are four sodium channel β subunit genes identified from mammalian genomes, all of which are expressed in the CNS (Goldin, 2001; Yu et al., 2003).

Most of the available information on the actions of pyrethroids on mammalian sodium channels was obtained using native neurons. However, the overlapping patterns of sodium channel subunit expression in the CNS (Felts et al., 1997; Whitaker et al., 2001) limit the utility of native neuronal preparations to identify isoform-dependent differences in pharmacology. This limitation can be overcome by the expression of cloned individual sodium channel isoforms or defined combinations of sodium channel subunits in heterologous expression systems. Available information on the sensitivity of individual mammalian sodium channel isoforms to pyrethroids is derived primarily from expression studies using the Xenopus laevis oocyte system. Rat Nav1.2 sodium channels, which are abundantly expressed in the adult CNS, are relatively insensitive to modification by deltamethrin and other pyrethroids (Smith and Soderlund, 1998; Vais et al., 2000a; Meacham et al., 2008). By contrast rat Nav1.8 channels, which are resistant to block by tetrodotoxin and restricted in distribution to the peripheral nervous system, are sensitive to modification by a wide structural variety of pyrethroids (Smith and Soderlund, 2001; Soderlund and Lee, 2001; Choi and Soderlund, 2006). Recent studies show that the rat Nav1.3 isoform is much more sensitive to modification by pyrethroids, especially those of the Type II structural class, than the rat Nav1.2 isoform (Meacham et al., 2008; Tan and Soderlund, 2009).

The difference in pyrethroid sensitivity between the rat Nav1.2 and Nav1.3 isoforms highlights the need for information on the relative pyrethroid sensitivities of other sodium channel isoforms that are expressed in the CNS. The Nav1.6 isoform is the most abundantly-expressed sodium channel α subunit in the adult brain (Auld et al., 1988) where it is preferentially expressed in regions of brain axons associated with action potential initiation (Hu et al., 2009). Nav1.6 is also the predominant isoform at nodes of Ranvier and is expressed in presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes of the neocortex and cerebellum (Caldwell et al., 2000). This pattern of expression implicates an important role for Nav1.6 sodium channels in both electrical and chemical signaling in the brain. The coincident expression of the Nav1.6, β1 and β2 sodium channel subunits in many brain regions (Whitaker et al., 2000; Shah et al., 2001; Schaller and Caldwell, 2003) suggests that Nav1.6 sodium channels exist in the brain predominantly as ternary complexes with the β1 and β2 subunits.

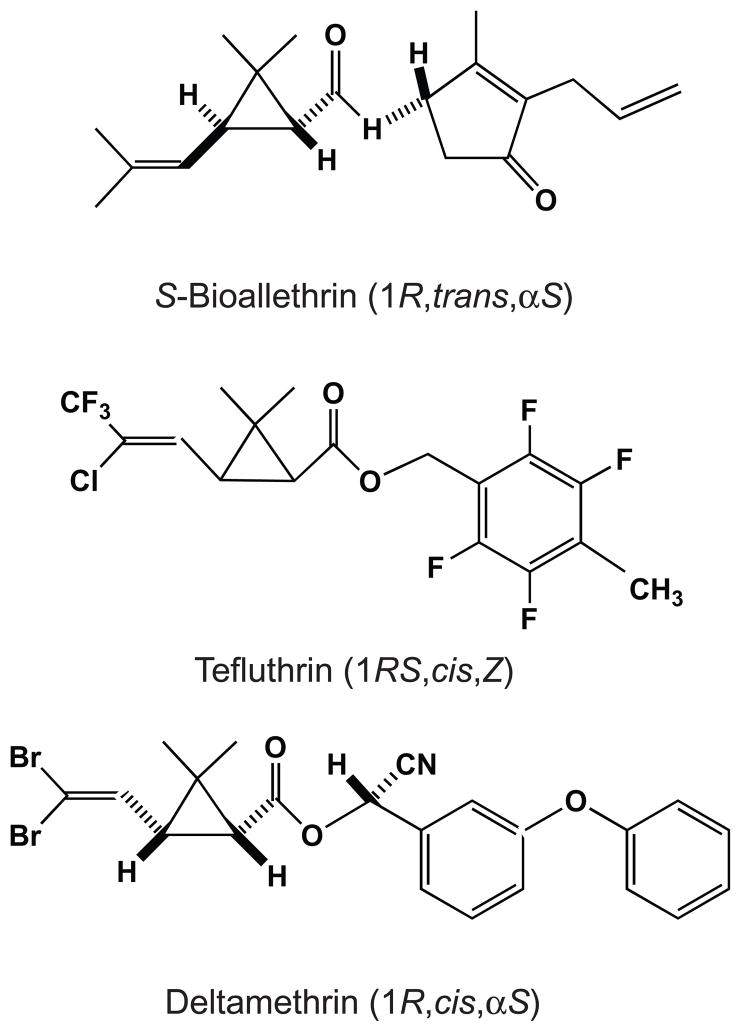

Here we describe the action of three commercial pyrethroid insecticides, S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin and deltamethrin (Fig. 1), on the rat the Nav1.6 sodium channel α subunit isoform coexpressed with the rat β1 and β2 subunits in Xenopus oocytes. We document marked differences between these three compounds in the kinetic properties of pyrethroid-modified channels, the relative importance of resting and use-dependent modification, and overall pyrethroid sensitivity. Direct comparative studies also show that the Nav1.6 isoform is more sensitive to modification by tefluthrin and deltamethrin than the Nav1.2 isoform.

Figure 1.

Structures and isomeric compositions of S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin and deltamethrin.

Materials and Methods

Cloned rat voltage-sensitive sodium channel subunit cDNAs were obtained from the following sources: Nav1.6 from L. Sangameswaran (Roche Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA); and Nav1.2 (adult splice variant), β1 and β2 from W.A. Catterall (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). Plasmid cDNAs were digested with restriction enzymes to provide linear templates for cRNA synthesis in vitro using a commercial kit (mMessage mMachine, Ambion, Austin, TX). The integrity of synthesized cRNA was determined by electrophoresis in 1% w/v agarose – formaldehyde gels.

Stage V–VI oocytes were removed from female X. laevis frogs (Nasco, Ft. Atkinson, WI) as described elsewhere (Smith and Soderlund, 2001). This procedure was performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and followed a protocol that was approved by the Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Each data set was derived from oocytes isolated from at least two different frogs. Oocytes were injected with 1:1:1 (mass ratio) mixtures of α subunit, β1 subunit and β2 subunit cRNAs (0.5 – 5 ng/oocyte); this mixture provided a ~9-fold molar excess of β1 and β2 cRNAs to ensure the preferential expression of α+β1+β2 complexes. Injected oocytes were incubated in ND-96 medium (in mM: 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 5 HEPES; adjusted to pH 7.6 at room temperature with NaOH) supplemented with 5% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% streptomycin/penicillin, and 1% sodium pyruvate (Goldin, 1992) at 19°C for 3–5 days until electrophysiological analysis of sodium currents.

Sodium currents were recorded from oocytes perfused with ND-96 at 19–21°C in the two-electrode voltage clamp configuration using an Axon Geneclamp 500B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Foster City, CA). Microelectrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillary tubes (1.0 mm O.D.; 0.5 mm I.D.; World Precision Instruments Inc., Sarasota, FL) and filled with 3 M KCl. Filled electrodes had resistances of 0.7–1.5 MΩ when immersed in ND-96 medium. Currents were filtered at 2 kHz with a low-pass 4-pole Bessel filter and digitized at 50 kHz (Digidata 1320A; Molecular Devices). To determine the voltage dependence of activation, oocytes were clamped at a membrane potential of −100 mV and currents were measured during a 40-ms depolarizing test pulse to potentials from −60 mV to 35 mV in 5-mV increments. Maximal peak transient currents were obtained upon depolarization to 0 mV (Nav1.6 channels) or −5 mV (Nav1.2 channels). To determine the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation, oocytes were clamped at a membrane potential of −140 mV followed by a 100-ms conditioning prepulse to potentials from −130 mV to 20 mV in 5-mV increments and then a 40-ms test pulse to 0 mV (Nav1.6 channels) or −5 mV (Nav1.2 channels). For determinations of use dependence, oocytes were given trains of 1 to 100 5-ms conditioning prepulses to 10 mV, separated by a 10-ms interpulse interval at the holding potential, followed by a 40-ms test pulse to 0 mV (Nav1.6 channels) or −5 mV (Nav1.2 channels). All experiments employed 10-s intervals between pulses or pulse trains to permit complete recovery from pyrethroid modification. Capacitive transients and leak currents were subtracted using the P/4 method (Bezanilla and Armstrong, 1977).

S-Bioallethrin (92.9 % purity) and deltamethrin (99.5%) were obtained from Bayer CropScience (Research Triangle Park, NC) and tefluthrin (98.8%) was obtained from Syngenta (Bracknell, Berks., UK). Pyrethroids were prepared as stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted with ND-96 immediately before use to final concentrations of 0.01 – 100 μM. The final DMSO concentration in the bath did not exceed 0.1%, a concentration that had no effect on sodium currents. Oocytes were perfused at 0.45 ml/min with pyrethroid in ND-96. All experiments with pyrethroids employed a disposable capillary perfusion system (Tatebayashi and Narahashi, 1994) and custom-fabricated single-use recording chambers (Smith and Soderlund, 2001) to prevent cross-contamination between oocytes. Concentration–effect experiments involved the sequential equilibration of a single oocyte with solutions of increasing pyrethroid concentration for 10 min prior to recording resting and use-dependent modification.

Data were acquired and analyzed using pClamp 8.2 (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA) and Origin 7.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA). The Boltzmann equation [y = (A1 − A2)/(1+e(x−x0)/dx) + A2] was used to fit conductance-voltage and sodium current inactivation data. Time constants for fast sodium channel inactivation were obtained by using the Chebyshev method in Origin 7.0 to fit the falling phase of the peak transient current to a double exponential decay model. Similarily, time constants for pyrethroid-induced sodium tail currents were obtained from fits of post-depolarization currents to a double exponential decay model. The conductance of the pyrethroid-induced sodium tail current, extrapolated to the moment of repolarization and normalized to the conductance of the peak current measured in the same oocyte in the absence of pyrethroid, was employed to calculate the fraction of sodium channels modified by each compound in each experiment as described previously (Tatebayashi and Narahashi, 1994). Fits of concentration–effect data to the Hill equation [(M=Mmax/{1+EC50/[pyrethroid]}n, where [pyrethroid] and EC50 represent the pyrethroid concentration employed and the concentration producing a half-maximal effect, respectively, and M and Mmax represent the effect observed and the maximal effect, respectively, were employed to calculate EC10 values.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Prism software package (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Comparisons of two or more mean values to a common control data set employed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for statistical significance. Comparisons of two means employed either a paired or unpaired Student’s t-test depending on the design of the experiment. Details of statistical analyses and levels of significance are given in footnotes to the Tables and in the Figure legends.

Results

Effects of pyrethroids on Nav1.6 sodium channel kinetics and gating

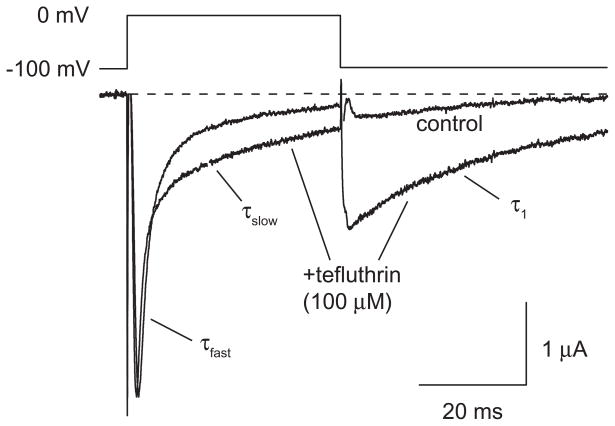

We employed S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin and deltamethrin at 100 μM, the highest concentration achievable in ND-96 perfusion medium, to maximize the extent of the modification of Nav1.6 sodium channels by each pyrethroid. We assessed the modification of channels in the resting state by holding the oocyte at a hyperpolarized membrane potential during equilibration with pyrethroid and measuring the pyrethroid-modified current during and after the first depolarizing pulse. Each compound produced the two characteristic pyrethroid effects on channel kinetics: slowing of inactivation during depolarization, evident as the broadening and incomplete decay of the peak transient current; and slowing of deactivation, evident as a sodium tail current visible following repolarization. These effects are illustrated by the currents recorded from an oocyte before and after tefluthrin exposure shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Representative control and tefluthrin (100 μM)-modified sodium currents recorded from an oocyte expressing rat Nav1.6 sodium channels using the indicated depolarization protocol. The dashed line indicates zero current. Values for the kinetic parameters τfast, τslow, and τ1 are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 compares the kinetics of fast inactivation of control and pyrethroid-modified sodium currents. In each case, the decay of the peak transient current was best fit by two first order processes yielding two time constants, τfast and τslow (see also Fig. 2). For all three pyrethroids, τfast and τslow values were significantly different from those for control currents but there was no consistent pattern among the three insecticides. S-Bioallethrin prolonged τfast whereas tefluthrin and deltamethrin accelerated this component. By contrast S-bioallethrin and deltamethrin accelerated τslow whereas tefluthrin prolonged this component.

Table 1.

Effects of three pyrethroids on the kinetics of fast inactivation and tail current decay of rat Nav1.6 sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

| Conditiona | Peak Current Inactivationb |

Tail Current Decayc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τfast | n | τslow | n | τ1 | n | |

| Control | 1.32 ± 0.03 | 40 | 10.93 ± 2.25 | 40 | ||

| + S-Bioallethrin | 2.11 ± 0.12d | 4 | 7.30 ± 0.35 d | 4 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 3 |

| + Tefluthrin | 1.12 ± 0.04 d | 12 | 19.00 ± 0.64 d | 12 | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 17 |

| + Deltamethrin | 1.02 ± 0.04 d | 12 | 8.33 ± 0.50 d | 12 | 21.3 ± 1.9 | 16 |

All pyrethroids assayed at 100 μM.

Time constants (ms) for the fast (τfast) and slow (τslow) components of sodium current inactivation; values are means ± SE for the indicated number of replicate experiments with different oocytes.

Time constants (ms) for the fast (τ1) component of tail current decay; values are means ± SE for the indicated number of replicate experiments with different oocytes.

Values were significantly different from control values (P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis).

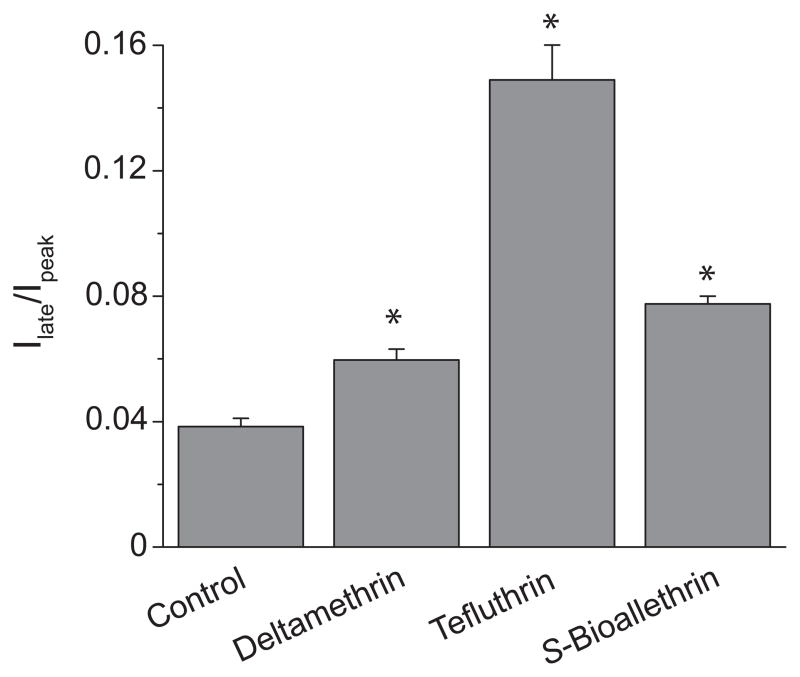

In the absence of insecticide, currents carried by Nav1.6 channels did not completely inactivate, resulting in a small persistent current evident at the end of a depolarizing pulse (see Fig. 2). Fig. 3 illustrates the amplitudes of the persistent currents obtained in the absence or presence of insecticides expressed as a fraction of the peak transient current in the same trace. The prolongation of τslow by tefluthrin resulted in a pronounced enhancement of the persistent current in the presence of this compound (see also Fig. 2) that was less evident with the other two pyrethroids (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Late currents measured in the absence and presence of pyrethroids (100 μM). Currents were recorded at the end of a 40-ms step depolarization from −100 mV to 0 mV. Values are means ± SE of 37 (control), 3 (S-bioallethrin), 11 (tefluthrin) or 12 (deltamethrin) separate experiments with different oocytes. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from control (P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis).

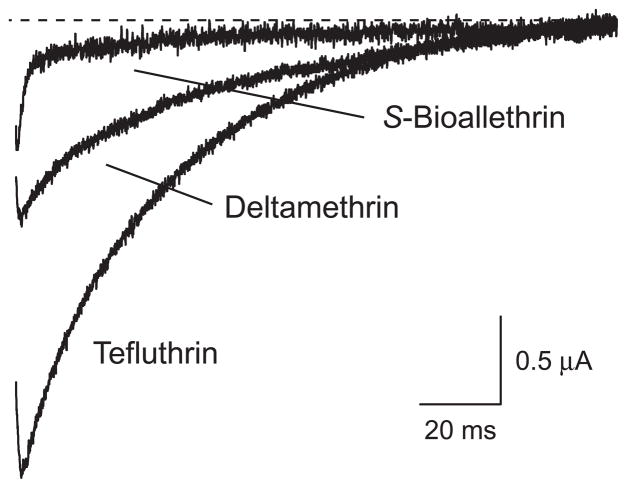

The kinetics of tail current decay differed markedly among the three compounds examined in this study (Fig. 4). The decay of pyrethroid-induced tail currents was best fit by a two-component first-order model. The predominant fast component (τ1; see Table 1) was reproducible and described the distinctive tail current decay observed for each compound. In contrast the minor slow component (τ2; data not shown) was highly variable between oocytes and not related to pyrethroid structure. The slow nonspecific component of tail currents is evident in the S-bioallethrin tail current trace illustrated in Fig. 4. Tail currents induced by S-bioallethrin decayed completely within a few ms and in some experiments were difficult to resolve from unsubtracted elements of the capacitive transients associated with membrane repolarization. The τ1 values for tail currents induced by tefluthrin and deltamethrin were approximately 4-fold and 9-fold more larger, respectively, than that for S-bioallethrin-induced currents (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Representative sodium tail currents recorded from oocyte expressing rat Nav1.6 sodium channels following exposure to S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin or deltamethrin (100 μM). Traces show currents recorded beginning 0.5 ms after repolarization to −100 mV from a step depolarization to 0 mV. The dashed line indicates zero current.

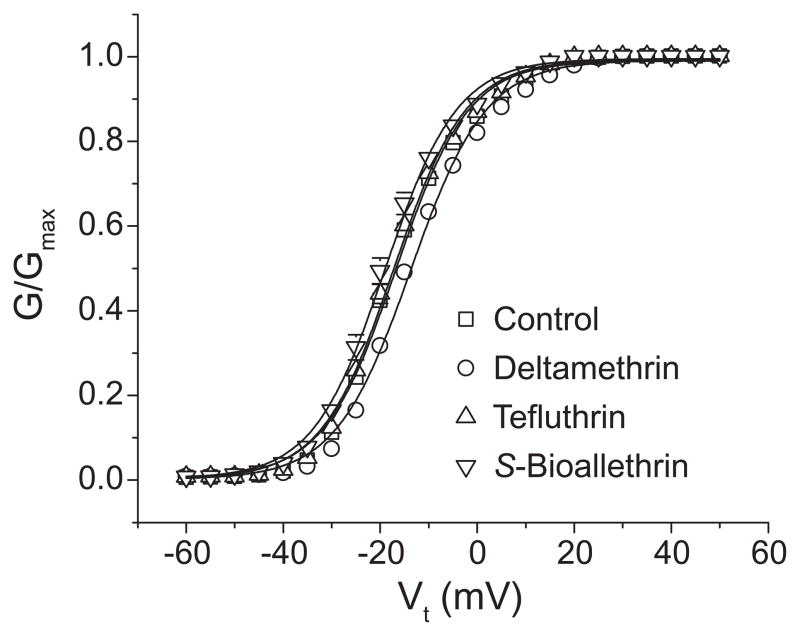

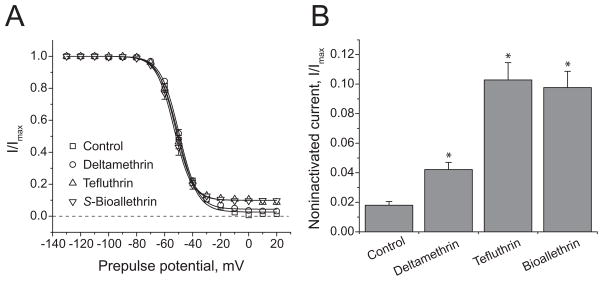

The effects of S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin and deltamethrin on the voltage-dependent activation and inactivation gating of Nav1.6 channels are illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6 and the statistical analyses of these data are summarized in Table 2. The three pyrethroids had minimal effects on the voltage dependence of either activation (Fig. 5) or steady-state inactivation (Fig. 6A). Analyses of multiple replicate experiments identified a small but statistically significant depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation in the presence of deltamethrin. The most notable effect of pyrethroids on channel gating was the enhancement of a small but reproducible component of current that did not inactivate following depolarizing prepulses above 0 mV (Figs. 6A and 6B). This inactivation-resistant current, which represented approximately 2% of the total current in the absence of insecticide, was increased approximately five-fold in the presence of either S-bioallethrin or tefluthrin and approximately two-fold in the presence of deltamethrin. The enhancement of inactivation-resistant current by S-bioallethrin and tefluthrin was correlated with a change in the slope factor (K) of the inactivation curves for these compounds (Table 2), but this effect was statistically significant only for tefluthrin.

Figure 5.

Effects of S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin or deltamethrin (100 μM) on the voltage dependence of activation of rat Nav1.6 sodium channels expressed in oocytes. Conductances of peak transient sodium currents measured upon depolarization from −100 mV to a range of test potentials are plotted as a function of test potential. Values are means; of 19 (control), 4 (S-bioallethrin), 6 (tefluthrin) or 9 (deltamethrin) separate experiments with different oocytes; bars show SE values larger than the data point symbols. Conductance – voltage curves were fitted to mean conductance values using the Boltzmann equation.

Figure 6.

(A) Effects of S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin or deltamethrin (100 μM) on the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation of rat Nav1.6 sodium channels expressed in oocytes. Amplitudes of peak transient currents obtained during a 40-ms test depolarization to 0 mV following 100-msec conditioning prepulses from −140 mV to a range of conditioning potenticals are plotted as a function of prepulse potential. Values are means of 19 (control), 4 (S-bioallethrin), 6 (tefluthrin) or 9 (deltamethrin) separate experiments with different oocytes; bars show SE values larger than the data point symbols. The dashed line indicates zero current (complete inactivation). Current – voltage curves were fitted to mean current amplitude values using the Boltzmann equation. (B) Effects of S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin or deltamethrin (100 μM) on the amplitude of the inactivation-resistant component of sodium current during a 40-ms test depolarization to 0 mV following a 100-ms conditioning prepulse to 20 mV. Values are means ± SE as in Fig. 6A. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from control (P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis).

Table 2.

Effects of three pyrethroids on the activation and inactivation gating parameters of rat Nav1.6 sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytesa.

| Condition | n | Activation | Inactivation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V0.5 | K | V0.5 | K | ||

| Control | 19 | −17.0 ± 0.4 | 8.02 ± 0.23 | −50.3 ± 0.3 | 7.02 ± 0.13 |

| +S-Bioallethrin | 4 | −19.2 ± 1.1 | 7.78 ± 0.52 | −52.8 ± 1.1 | 6.24 ± 0.23 |

| +Tefluthrin | 6 | −17.0 ± 1.0 | 8.06 ± 0.21 | −52.3 ± 1.2 | 6.03 ± 0.10b |

| +Deltamethrin | 9 | −13.7 ± 0.6b | 8.03 ± 0.26 | −50.2 ± 0.9 | 7.01 ± 0.34 |

Values are means ± SE calculated from fits of individual data sets obtained in the absence or presence of 100 μM S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin or deltamethrin to the Boltzmann equation; V0.5, midpoint potential (mV) for voltage-dependent activation or inactivation; K, slope factor; n, number of replicate experiments.

Significantly different from control (P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis).

Resting and use-dependent modification of Nav1.6 sodium channels by pyrethroids

We employed the normalized conductance of the pyrethroid-induced sodium tail current (Tatebayashi and Narahashi, 1994) to calculate the fraction of Nav1.6 sodium channels that were modified following equilibration with 100 μM S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin or deltamethrin. To assess modification in the resting state, we equilibrated oocytes with pyrethroid at a hyperpolarized holding potential and determined the extent of modification from the tail current obtained following the first depolarizing pulse. The tefluthrin-modified current shown in Fig. 2 is typical of such results. The greatest extent of resting modification of Nav1.6 channels under these conditions was observed with tefluthrin (14.2 ± 0.9%; n = 15), whereas S-bioallethrin ( 5.7 ± 1.1%; n = 4) and deltamethrin (2.5 ± 0.3%; n = 12) were less effective as modifiers of resting channels.

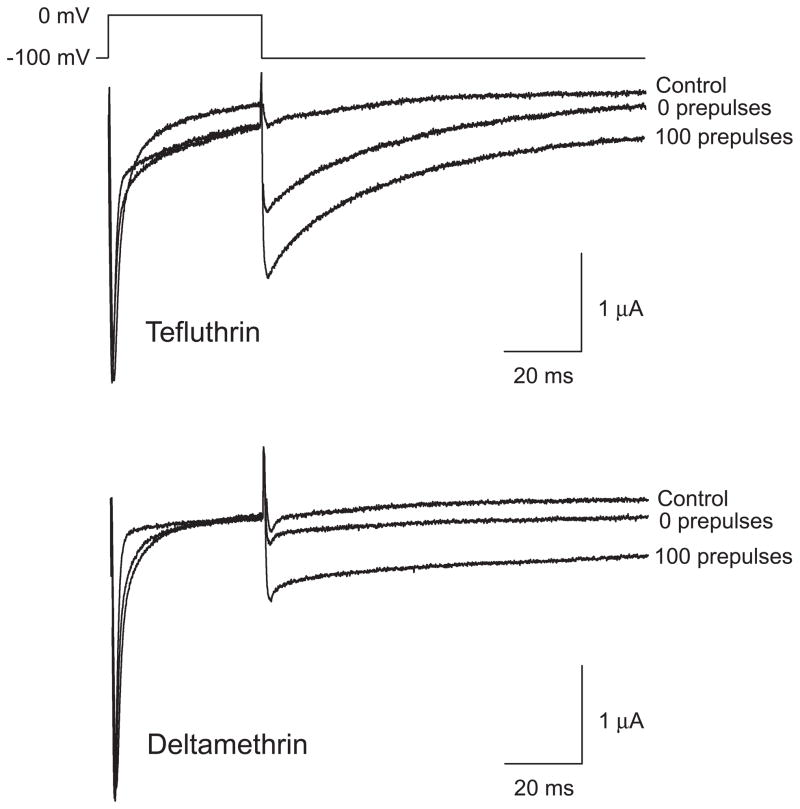

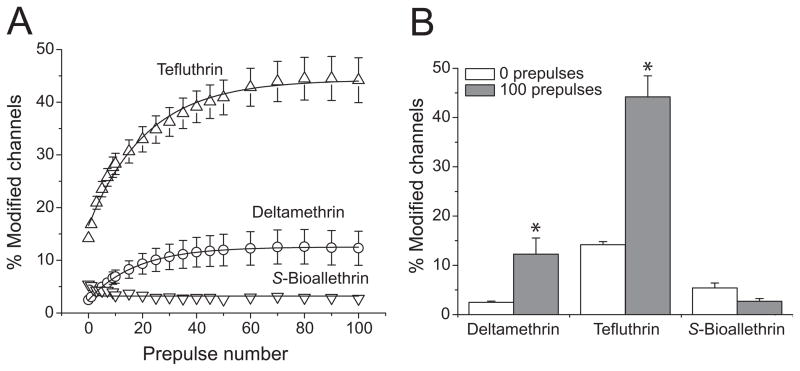

Modification of both insect and mammalian sodium channels by some pyrethroids is enhanced by repeated depolarization (reviewed in Soderlund, 2010a). We therefore determined the effect of trains of high-frequency depolarizing prepulses on the extent of modification of Nav1.6 sodium channels by the three pyrethroids. Modification by tefluthrin and deltamethrin was strongly enhanced by repetitive depolarization (Fig. 7). For deltamethrin, the extent of modification increased with prepulse number up to 50 prepulses and then remained stable; for tefluthrin, the extent of modification increased with prepulse number up to 80 prepulses and then remained stable (Fig. 8A). In contrast to these results, modification by S-bioallethrin decreased slightly upon repetitive depolarization (Fig. 8A). Figure 8B compares the extent of resting (0 prepulses) and maximal use-dependent (100 prepulses) modification by all three pyrethroids. For tefluthrin and deltamethrin, repetitive depolarization increased the extent of channel modification 2.8-fold and 3.7-fold, respectively.

Figure 7.

Representative traces recorded from oocytes expressing Nav1.6 sodium channels exposed to tefluthrin (top) or deltamethrin (bottom) using the indicated pulse protocol. Control traces were recorded prior to insecticide exposure. Following equilibration with insecticide traces were recorded before or after the application of a high-frequency train of 100 depolarizing prepulses.

Figure 8.

(A) Effect of repeated depolarizing prepulses on the extent of modification of rat Nav1.6 sodium channels by S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin and deltamethrin. Values are means ± SE of 4 (S-bioallethrin), 15 (tefluthrin) or 12 (deltamethrin) separate experiments with different oocytes. (B) Comparison of the extent of resting (after 0 prepulses) and maximal use-dependent (after 100 prepulses) modification of rat Nav1.6 sodium channels by S-bioallethrin, tefluthrin and deltamethrin. Values for use-dependent modification marked with asterisks are significantly different from values for the resting modification by the same compound (paired t-tests, P < 0.05).

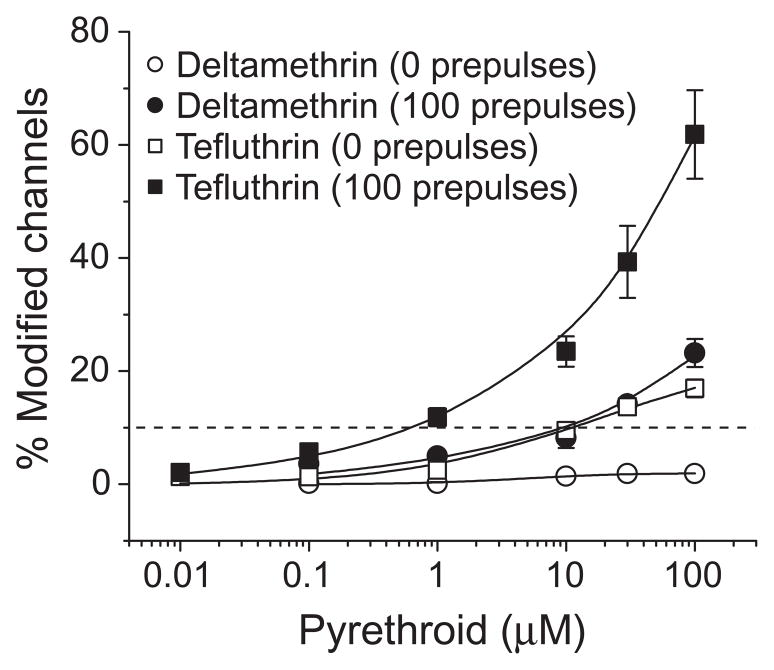

We determined the extent of modification of Nav1.6 channels after either 0 prepulses or 100 prepulses by a range of tefluthrin and deltamethrin concentrations to define the concentration dependence of the resting and maximal use-dependent modification of both channels by these compounds (Fig. 9). Concentration-dependent responses were observed for both resting and use-dependent modification by tefluthrin and for use-dependent modification by deltamethrin, but resting modification by deltamethrin was barely detectable at the highest concentration examined. Comparisons of EC10 values derived from these data (Table 3) indicated that repetitive depolarization increased the sensitivity of Nav1.6 channels to tefluthrin approximately 15-fold. Tefluthrin was approximately 10-fold more potent than deltamethrin as a modifier of Nav1.6 channels using use-dependent modification as a basis for comparison.

Figure 9.

Concentration dependence of resting (0 prepulses) and use-dependent (100 prepulses) modification of Nav1.6 sodium channels by tefluthrin and deltamethrin. Values are means ± SE of 5 separate experiments with each compound. The dashed line indicates 10% channel modification.

Table 3.

Relative sensitivity of rat Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes to resting (0 prepulses) and use-dependent (100 prepulses) modification by tefluthrin and deltamethrin.

| Channel | Compound | EC10, μMa |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Prepulses | 100 Prepulses | ||

| Nav1.6 | Tefluthrin | 14.1 ± 3.7 | 0.95 ± 0.22 |

| Deltamethrin | NDb | 9.8 ± 1.9 | |

| Nav1.2 | Tefluthrin | 222 ± 82 | 16.9 ± 5.5 |

| Deltamethrin | ND | 143 ± 9 | |

EC10 values were calculated as described in the Materials and Methods; values are means ± SE of 5 separate experiments for each channel–compound combination.

Value not determined.

Relative pyrethroid sensitivity of Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 sodium channels

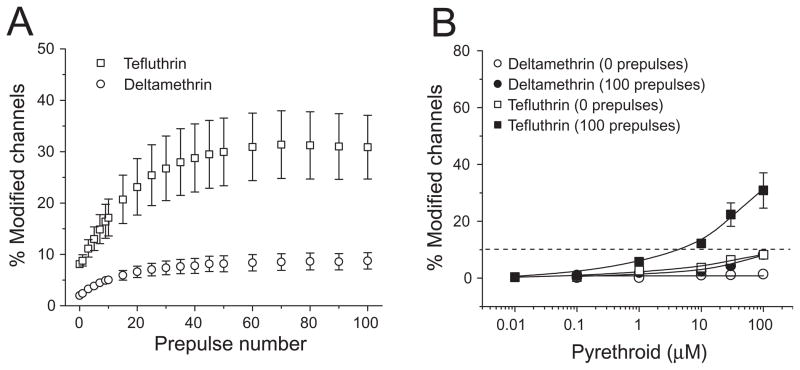

To facilitate comparison of the pyrethroid sensitivity of Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 channels we determined effect of trains of high-frequency depolarizing prepulses on the extent of modification of Nav1.2 sodium channels by 100 μM tefluthrin or deltamethrin. The results obtained in these experiments (Fig. 10A) were qualitatively similar to those obtained with Nav1.6 channels (see Fig. 8A). We determined the extent of modification of Nav1.2 channels by a range of tefluthrin and deltamethrin concentrations after either 0 prepulses or 100 prepulses to define the concentration dependence of the resting and maximal use-dependent modification by these compounds (Fig. 10B). Comparison of EC10 values derived from these data (Table 3) showed that repetitive depolarization increased the sensitivity of Nav1.2 channels to tefluthrin approximately 13-fold. Similarly values obtained with the two isoforms (Table 3) showed that Nav1.6 channels were 16-fold more sensitive to resting modification by tefluthrin, 18-fold more sensitive to use-dependent modification by tefluthrin, and 16-fold more sensitive to use-dependent modification by deltamethrin.

Figure 10.

(A) Effect of repeated depolarizing prepulses on the extent of modification of rat Nav1.2 sodium channels by tefluthrin and deltamethrin. Values are means ± SE of 8 (tefluthrin) or 12 (deltamethrin) separate experiments with different oocytes. (B) Concentration dependence of resting (0 prepulses) and use-dependent (100 prepulses) modification of Nav1.2 sodium channels by tefluthrin and deltamethrin. Values are means ± SE of 5 separate experiments with each compound. The dashed line indicates 10% channel modification.

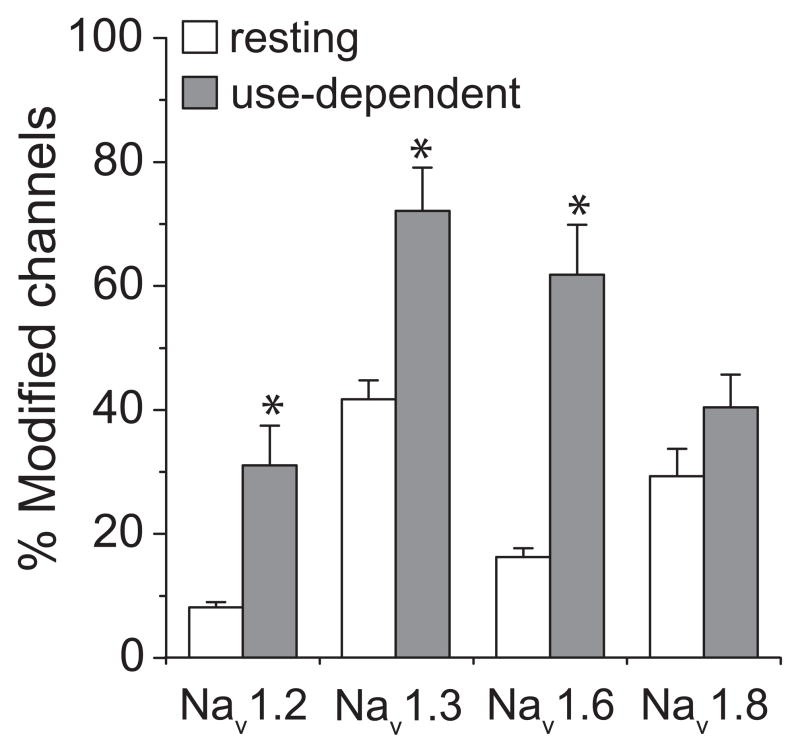

To place the difference in pyrethroid sensitivity between Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 sodium channels in context, we compared the extent of modification of these two channels by tefluthrin to corresponding data obtained with two other rat sodium channel isoforms. Figure 11 compares the extent of both resting and use-dependent (after 100 prepulses) modification by tefluthrin (100 μM) of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels from this study to comparable data from previous studies of rat Nav1.3 (Tan and Soderlund, 2009) and rat Nav1.8 channels (Choi and Soderlund, 2006). Nav1.2 channels were the least sensitive among the four channels examined. Nav1.6 were almost as sensitive as Nav1.3 channels and more sensitive to use-dependent modification than Nav1.8 channels. Of the four isoforms, only Nav1.8 did not exhibit significant use-dependent enhancement of tefluthrin modification.

Figure 11.

Comparison of resting (0 prepulses) and use-dependent (100 prepulses) modification of four rat sodium channel isoforms by 100 μM tefluthrin. The Nav1.2, Nav1.3 and Nav1.6 isoforms were expressed with the rat β1 and β2 subunits whereas the Nav1.8 subunit was expressed without β subunits. Data for Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 channels are from this study (Figs. 8A and 10A); data for Nav1.3 and Nav1.8 channels are from previous studies in this laboratory (Choi and Soderlund, 2006; Tan and Soderlund, 2009) and are means ± SE of 6 (Nav1.3) and 3 (Nav1.8) separate experiments with different oocytes. Values for use-dependent modification marked with asterisks are significantly different from values for the resting modification of the same channel (paired t-tests, P < 0.05).

Discussion

The Nav1.6 sodium channel isoform is one of three isoforms (along with Nav1.1 and Nav1.2) that are abundantly expressed in the adult brain (Goldin, 2001). We expressed the rat Nav1.6 α subunit in Xenopus oocytes in combination with the rat β1 and β2 auxiliary subunits, giving heterotrimeric channel complexes that reflect the presumed structure of native channels in the brain (Catterall, 2000; Goldin, 2001). The gating and kinetic properties of rat, mouse and human Nav1.6 channels have been previously characterized following heterologous expression either in the Xenopus oocyte system (Dietrich et al., 1998; Smith et al., 1998a; Smith and Goldin, 1999; Zhou and Goldin, 2004) or in transfected mammalian cells (Burbidge et al., 2002; Herzog et al., 2003; Rush et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2008). In both systems Nav1.6 channels give sodium currents that activate and inactivate rapidly. Typically inactivation of Nav1.6 channels is incomplete, resulting in a small, persistent component of current visible at the end of a depolarizing pulse that is not commonly seen with other sodium channel isoforms. Persistent sodium currents are also found in Purkinje neurons, in which Nav1.6 is the predominant sodium channel isoform. The properties of rat Nav1.6 sodium channels that we describe here are fully consistent with the properties of these channels determined in previous studies.

This study represents the first characterization of the effects of pyrethroid insecticides on Nav1.6 sodium channels. The three compounds selected for this study exemplify the diversity of acute neurotoxic effects caused by pyrethroids (Soderlund et al., 2002; Soderlund, 2010b). S-Bioallethrin, an analog of the natural insecticide constituent pyrethrin I, is a member of the Type I structural class and produces the T intoxication syndrome in rodents. Deltamethrin, a member of the Type II structural class, produces effects in rodents that first defined the CS syndrome. Tefluthrin is a member of the Type I structural class but is atypical of Type I compounds in exhibiting high acute oral toxicity to rodents. Tefluthrin was not included in the original studies that classified pyrethroids according to intoxication syndromes, but a recent principal component analysis (Breckenridge et al., 2009) of a comparative behavioral neurotoxicity study of 12 pyrethroids (Weiner et al., 2009) grouped tefluthrin with other pyrethroids producing the T syndrome. The three pyrethroids used in this study differed both qualitatively and quantitatively in their modification of Nav1.6 sodium channels.

The rapidly-decaying sodium tail currents caused by S-bioallethrin were similar to those produced by this compound, cismethrin and permethrin, all Type I pyrethroids, in assays with the rat Nav1.8 sodium channel isoform in Xenopus oocytes (Choi and Soderlund, 2006). These currents are also typical of the effects of Type I compounds on voltage-clamped sodium currents in neuronal preparations (Soderlund, 1995; Soderlund, 2010b). A high concentration of S-bioallethrin produced only weak resting modification of Nav1.6 channels, and the extent of modification was not enhanced by repeated depolarization. This result implies that open channels or other channel states resulting from activation do not exhibit a higher affinity for this compound than channels in the resting state. The weak effects of S-bioallethrin at 100 μM on Nav1.6 channels prevented us from pursuing additional experiments at lower concentrations.

Deltamethrin produced slowly-decaying sodium tail currents with time constants approximately 10-fold greater than those caused by S-bioallethrin, an effect typical of Type II compounds (Soderlund, 1995; Soderlund, 2010b). Resting modification of Nav1.6 channels by deltamethrin was barely detectable, but the extent of modification was increased substantially by the application of trains of short depolarizing prepulses. Similarly, modification of Nav1.2 channels by deltamethrin was only observed following repetitive depolarization. The use-dependent effects of deltamethrin on both Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 channels in the present study is consistent with the actions of this compound and [1R,cis,αS]-cypermethrin, a close structural relative of deltamethrin, on insect sodium channels in the oocyte expression system (Smith et al., 1998b; Vais et al., 2000b).

The use-dependent effects of deltamethrin and related Type II pyrethroids have been interpreted as evidence for the preferential binding of these compounds to open sodium channels (reviewed in Soderlund, 2010a). This interpretation is the basis of a recently-proposed model of the pyrethroid receptor in which the pyrethroid binding site is associated with specific amino acid residues located in the inner pore of the channel in the open configuration (O’Reilly et al., 2006). Whereas the present studies implicate enhanced deltamethrin binding to a channel conformation that is achieved through activation they do not necessarily imply that this high-affinity conformation is the open state of the channel. Further studies are required to differentiate among the possible mechanisms underlying the use dependence of deltamethrin and other pyrethroids in these assays.

The actions of tefluthrin on Nav1.6 sodium channels included elements characteristic of both Type I (S-bioallethrin) and Type II (deltamethrin) effects. The decay of tefluthrin-induced tail currents exhibited kinetics intermediate between those induced by S-bioallethrin and deltamethrin. Tefluthrin produced readily-detectable resting modification of Nav1.6 channels but repetitive depolarization significantly enhanced its extent of channel modification, increasing the apparent affinity of Nav1.6 channels by approximately 15-fold. This combination of resting and use-dependent modification was also observed in parallel experiments with rat Nav1.2 sodium channels and in our previous studies of rat and human Nav1.3 sodium channels (Tan and Soderlund, 2009). These results suggest that tefluthrin binds to both resting channels and to channel conformations that result from activation. Moreover, activation increases the apparent affinity of channels for this compound. Although the actions of tefluthrin in these assays are similar in many respects to those of deltamethrin, a recent principal component analysis of behavioral neurotoxicity studies grouped tefluthrin with pyrethroids previously characterized as producing the T syndrome of intoxication commonly associated with the Type I structural class (Breckenridge et al., 2009). It is therefore not possible at present to correlate specific features of sodium channel modification in vitro with the production of the T or CS intoxication syndrome in vivo.

Comparison of EC10 values for use-dependent modification revealed tefluthrin to be approximately 10-fold more potent than deltamethrin as a modifier of Nav1.6 sodium channels. The acute oral LD50 of tefluthrin to rats is 22 mg/kg, approximately 5-fold lower than the corresponding value for deltamethrin (95 mg/kg) (Soderlund et al., 2002), making tefluthrin the pyrethroid in current use with the highest acute toxicity to mammals. The greater potency of tefluthrin than deltamethrin as a modifier of Nav1.6 sodium channels is therefore fully consistent with the relative acute toxicities of these two compounds.

The parallel studies reported here of the actions of deltamethrin and tefluthrin on Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 channels permit the unambiguous assessment of the relative pyrethroid sensitivity of these two sodium channel isoforms that are abundantly expressed in the adult brain. Previous studies (Smith and Soderlund, 1998; Vais et al., 2000a; Meacham et al., 2008) have shown that Nav1.2 sodium channels are relatively insensitive to pyrethoids. Our data show that Nav1.6 sodium channels are approximately 15-fold more sensitive than Nav1.2 sodium channels to use-dependent modification by deltamethrin and both resting and use-dependent modification by tefluthrin. The greater sensitivity of Nav1.6 channels strongly implicates their involvement in the neurotoxic actions of pyrethroids in the adult CNS.

Previous studies have shown that the rat Nav1.3 channel, the predominant isoform in the developing CNS, and the rat Nav1.8 channel, expressed in peripheral sensory neurons, are also much more sensitive than the Nav1.2 sodium channel to pyrethroids (Smith and Soderlund, 2001; Choi and Soderlund, 2006; Meacham et al., 2008; Tan and Soderlund, 2009). Using the resting and use-dependent actions tefluthrin as a basis of comparison, our data show that Nav1.6 sodium channels are more sensitive than Nav1.8 sodium channels and nearly as sensitive as Nav1.3 channels. This relationship provides additional evidence of the likely importance of Nav1.6 sodium channels as targets for pyrethroid intoxication.

To date the characterization of pyrethroid effects on sodium channels of defined isoform and subunit composition has relied almost exclusively on the Xenopus oocyte expression system. Whereas the oocyte system readily permits the manipulation of channel structure as a variable, the biophysical and pharmacological properties of channels expressed in the oocyte membrane environment may not fully reproduce those in native neurons or mammalian cell expression systems due to species differences in membrane composition and post-translational modification. Moreover, studies of lipophilic ligands in oocytes are complicated by the extensive partitioning of insecticide into the oocyte membrane during perfusion (Harrill et al., 2005). As a result, relatively high concentrations of pyrethroid are required to achieve extensive channel modification in oocyte assays and concentration – effect curves, such as those shown in Figs. 9 and 10B, and shallow and incomplete. Further studies involving the direct comparison of the actions of pyrethroids on channels of defined subunit structure in oocytes and in mammalian cells are needed to clarify the influence of expression systems on channel properties and pyrethroid action.

To summarize, the present study provides new information on the action of pyrethroid insecticides on sodium channels containing the Nav1.6 α subunit. This isoform is substantially more sensitive to pyrethroid insecticides than is Nav1.2, both of which are expressed abundantly in the adult brain. The sensitivity of Nav1.6 sodium channels, coupled with their expression in regions of the brain whose function is selectively disrupted during pyrethroid intoxication and region of brain neurons involved in action potential generation and synaptic transmission, imply that actions of pyrethroids on Nav1.6-containing channels are likely to be important role in determining the systemic neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant number R01-ES013686 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. We thank P. Adams and S. Kopatz for technical assistance and S. McCavera and R. von Stein for critical reviews of the manuscript.

Role of Funding Sources

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences provided sfinancial support but no other input into this project or the manuscript derived from it.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statements for Authors

Neither J. Tan nor D. M. Soderlund have conflicts of interest regarding the research described in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Auld VJ, Goldin AL, Krafte DS, Marshall J, Dunn JM, Catterall WA, Lester HA, Davidson N, Dunn RJ. A rat brain Na+ channel α subunit with novel gating properties. Neuron. 1988;1:449–461. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F, Armstrong CM. Inactivation of the sodium channel. J Gen Physiol. 1977;70:549–566. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.5.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist JR. Neuroreceptor mechanisms in pyrethroid mode of action and resistance. In: Roe M, Kuhr RJ, editors. Reviews in Pesticide Toxicology. Toxicology Communications; Raleigh, NC: 1993a. pp. 181–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist JR. Toxicology, mode of action and target site-mediated resistance to insecticides acting on chloride channels. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1993b;106C:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(93)90138-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge CB, Holden L, Sturgess N, Weiner M, Sheets L, Sargent D, Soderlund DM, Choi JS, Symington S, Clark JM, Burr S, Ray D. Evidence for a separate mechanism of toxicity for the Type I and Type II pyrethroid insecticides. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:S17–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbidge SA, Dale TJ, Powell AJ, Whitaker WRJ, Xie XM, Romanos MA, Clare JJ. Molecular cloning, distribution and functional analysis of the Nav1.6 voltage-gated sodium channel from human brain. Mol Brain Res. 2002;103:80–90. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JH, Schaller KL, Lasher RS, Peles E, Levinson SR. Sodium channel Nav1.6 is localized nodes of Ranvier, dendrites, and synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5616–5620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090034797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yu FH, Sharp EM, Beacham D, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional properties and differential modulation of Nav1.6 sodium channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Soderlund DM. Structure-activity relationships for the action of 11 pyrethroid insecticides on rat Nav1.8 sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;211:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich PS, McGivern JG, Delgado SG, Koch BD, Eglen RM, Hunter JC, Sangameswaran L. Functional analysis of a voltage-gated sodium channel and its splice variant from rat dorsal root ganglia. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2262–2272. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M. Chemicals in insect control. In: Casida JE, Quistad GB, editors. Pyrethrum flowers: production, chemistry, toxicology, and uses. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Felts PA, Yokoyama S, Dib-Hajj S, Black JA, Waxman SG. Sodium channel α-subunit mRNAs I, II, III, NaG, Na6 and hNE (PN1): different expression patters in developing rat nervous system. Mol Brain Res. 1997;45:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin AL. Maintenance of Xenopus laevis and oocyte injection. Meth Enzymol. 1992;207:266–297. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07017-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin AL. Resurgence of sodium channel research. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:871–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin AL, Barchi RL, Caldwell JH, Hofmann F, Howe JR, Hunter JC, Kallen RC, Mandel G, Meisler MH, Netter YB, Noda N, Tamkun MM, Waxman SG, Wood JN, Catterall WA. Nomenclature of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;28:365–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrill JA, Meacham CA, Shafer TJ, Hughes MF, Crofton KM. Time and concentration dependent accumulation of [3H]-deltamethrin in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Toxicol Lett. 2005;157:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog RI, Cummins TR, Ghassemi F, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Distinct repriming and closed-state inactivation kinetics of Nav1.6 and Nav1.7 sodium channels in mouse spinal sensory neurons. J Physiol. 2003;551:741–750. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Tian C, Yang M, Hou H, Shu Y. Distinct contributions of Nav1.6 and Nav1.2 in action potential initiation and backpropagation. Nature Neurosci. 2009;12:996–1002. doi: 10.1038/nn.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence LJ, Casida JE. Pyrethroid toxicology: mouse intracerebral structure-toxicity relationships. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1982;18:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Meacham CA, Brodfuehrer PD, Watkins JA, Shafer TJ. Developmentally-regulated sodium channel subunits are differentially sensitive to α-cyano containing pyrethroids. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narahashi T. Neuronal ion channels as the target sites of insecticides. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;78:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1996.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly AO, Khambay BPS, Williamson MS, Field LM, Wallace BA, Davies TGE. Modelling insecticide binding sites at the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biochem J. 2006;396:255–263. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AM, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Electrophysiological properties of two axonal sodium channels, Nav1.2 and Nav1.6, expressed in mouse spinal sensory neurons. J Physiol. 2005;564:803–815. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.083089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller KL, Caldwell JH. Expression and distribution of voltage-gated sodium channels in the cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2003;2:2–9. doi: 10.1080/14734220309424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BS, Stevens EB, Pinnock RD, Dixon AK, Lee K. Developmental expression of the novel voltage-gated sodium channel auxiliary subunit β3, in rat CNS. J Physiol. 2001;534:763–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MR, Goldin AL. A mutation that causes ataxia shifts the voltage-dependence of the Scn8a sodium channel. NeuroReport. 1999;10:3027–3031. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199909290-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MR, Smith RD, Plummer NW, Meisler MH, Goldin AL. Functional analysis of the mouse Scn8a sodium channel. J Neurosci. 1998a;18:6093–6102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06093.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Ingles PJ, Soderlund DM. Actions of the pyrethroid insecticides cismethrin and cypermethrin on house fly Vssc1 sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1998b;38:126–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(1998)38:3<126::AID-ARCH3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Soderlund DM. Action of the pyrethroid insecticide cypermethrin on rat brain IIa sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. NeuroToxicology. 1998;19:823–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Soderlund DM. Potent actions of the pyrethroid insecticides cismethrin and cypermethrin on rat tetrodotoxin-resistant peripheral nerve (SNS/PN3) sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2001;70:52–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(1998)38:3<126::AID-ARCH3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM. Mode of action of pyrethrins and pyrethroids. In: Casida JE, Quistad GB, editors. Pyrethrum Flowers: Production, Chemistry, Toxicology, and Uses. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM. State-dependent modification of voltage-gated sodium channels by pyrethroids. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2010a;97:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM. Toxicology and mode of action of pyrethroid insecticides. In: Krieger RI, editor. Hayes’ Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology. Elsevier; New York: 2010b. pp. 1665–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM, Clark JM, Sheets LP, Mullin LS, Piccirillo VJ, Sargent D, Stevens JT, Weiner ML. Mechanisms of pyrethroid toxicity: implications for cumulative risk assessment. Toxicology. 2002;171:3–59. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM, Lee SH. Point mutations in homology domain II modify the sensitivity of rat Nav1.8 sodium channels to the pyrethroid cismethrin. Neurotoxicology. 2001;22:755–765. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(01)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Soderlund DM. Human and rat Nav1.3 voltage-gated sodium channels differ in inactivation properties and sensitivity to the pyrethroid insecticide tefluthrin. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatebayashi H, Narahashi T. Differential mechanism of action of the pyrethroid tetramethrin on tetrodotoxin-sensitive and tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:595–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vais H, Atkinson S, Eldursi N, Devonshire AL, Williamson MS, Usherwood PNR. A single amino acid change makes a rat neuronal sodium channel highly sensitive to pyrethroid insecticides. FEBS Lett. 2000a;470:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vais H, Williamson MS, Goodson SJ, Devonshire AL, Warmke JW, Usherwood PNR, Cohen CJ. Activation of Drosophila sodium channels promotes modification by deltamethrin: reductions in affinity caused by knock-down resistance mutations. J Gen Physiol. 2000b;115:305–318. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschoyle RD, Aldridge WN. Structure-activity relationships of some pyrethroids in rats. Arch Toxicol. 1980;45:325–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00293813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner ML, Nemec M, Sheets L, Sargent D, Breckenridge C. Comparative functional observational battery of twelve commercial pyrethroid insecticides in male rats following acute oral exposure. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:S1–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker WRJ, Clare JJ, Powell AJ, Chen YH, Faull RLM, Emson PC. Distribution of voltage-gated sodium channel α-subunit and β-subunit mRNAs in human hippocampal formation, cortex, and cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:123–139. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000619)422:1<123::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker WRJ, Faull RLM, Waldvogel HJ, Plumpton CJ, Emson PC, Clare JJ. Comparative distribution of voltage-gated sodium channel proteins in human brain. Mol Brain Res. 2001;88:37–53. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Westenbroek RE, Silos-Santiago I, McCormick KA, Lawson D, Ge P, Ferriera H, Lilly J, DiStefano P, Catterall WA, Scheuer T, Curtis R. Sodium channel β4, a new disulfide-linked auxiliary subunit with similarity to β2. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7577–7585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Goldin AL. Use-dependent potentiation of the Nav1.6 sodium channel. Biophys J. 2004;87:3862–3872. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]