Abstract

Background

A proportion of women planning to give birth in a midwifery unit will experience complications during labour that necessitate transfer to an obstetric unit. Local guidelines for the transfer of women in labour have the potential to impact on quality of care and the safety of the transfer process.

Objective

To systematically appraise the quality of local NHS guidelines on the transfer of women from midwifery unit to obstetric unit during labour.

Methods

Guidelines were requested from all 52 NHS hospital trusts in England with midwifery units. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Instrument was used to evaluate the quality of the guidelines received.

Results

Relevant guidelines were received from 34 (65%) trusts. No guidelines scored on the ‘editorial independence’ domain. The mean score on ‘scope and purpose’ (56.2%), concerned with the aims, clinical questions and target patient population of the guideline, was higher than for other domains: ‘clarity and presentation’ (language and format) 45.3%, ‘stakeholder involvement’ (representation of users’ views) 15.3%, ‘rigour of development’ (process used to develop guideline) 15.0%, ‘applicability’ (organisational, behavioural and cost implications of applying guideline) 7.1%. Only three guidelines were recommended for use in clinical practice.

Conclusions

We believe this to be the first systematic appraisal of the quality of local NHS guidelines. Overall these local guidelines were of poor quality. It is not clear whether the quality of these midwifery guidelines is typical of local guidelines in other clinical areas, but this study raises fundamental questions about the appropriate development of high-quality local clinical guidelines.

BACKGROUND

UK government policy since the early 1990s has been designed to give women a choice of settings for labour and birth, including care in a midwifery unit (MU).1 In the UK, NHS MUs can be either ‘freestanding,’ that is not on the same site as any obstetric unit, or ‘alongside,’ that is in the same building or on the same site as an obstetric unit.2 They provide midwife-led care for women who are at low risk of complications at the time of onset of labour and who want, and can safely choose, a low-tech approach to birth.3 Inevitably a proportion of women with straightforward pregnancies who intend to give birth in an MU will experience complications during or immediately after labour that necessitate transfer to a consultant-led obstetric unit. Available data indicate wide variation in estimates of intrapartum transfer rates, both within types of MU and between freestanding and alongside MUs.3

Local clinical guidelines for the transfer of women in labour are a possible factor in variation in transfer rates and have the potential to impact on quality of care and the safety of the transfer process. Guidelines have been defined as ‘system-atically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances’ with the specific purpose to ‘make explicit recommendations with adefinite intent to influence what clinicians do.’4 5 Recently published national guidelines for the care of healthy women and babies during childbirth in England and Wales cover indications for intrapartum transfer, but do not give comprehensive guidance on the process of transfer, including, for example, decision-making and communication.6 A recent report on the minimum standards for the organisation and delivery of care in labour recommended that, ‘There should be written multidisciplinary evidence-based clinical guidelines, which are accessible and reviewed every three years at each birth setting… [and that these] should include… management of transfer of mother and/or baby to obstetric unit.’ (p. 14).7

The proliferation of clinical guidelines over recent years has been accompanied by a growing recognition that the quality of guidelines varies and of the need for recognised criteria against which to judge guideline quality.8 While at present there is little evidence about the safety of the transfer process, good-quality local clinical guidelines have the potential to improve the quality, safety and appropriateness of care for women experiencing complications during labour in an MU. This study aimed to systematically appraise the quality of local NHS guidelines on the transfer of women from MU to obstetric unit during labour and to consider whether the same standards that are applied to the quality of guidelines developed at national level and by professional organisations can be applied to guidelines developed locally.

METHOD

Data collection

Data from the Healthcare Commission’s (HCC) Maternity Services Review were used to identify all NHS hospital trusts in England with at least one MU (some trusts have more than one MU).9 All these trusts indicated that they had at least one guideline relating to the transfer of women in labour and thus formed the sampling frame for this study. In October 2007, each MU was contacted by email and asked to provide any guidelines and/or protocols used in their MU relating to the transfer of women during labour. A further email was sent in December 2007 to units in trusts that had not yet responded.

Quality appraisal

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument, an internationally developed generic tool for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines, was used in this study.10 Using this instrument, each guideline is assessed using 23 items organised into six domains. Each domain relates to a different dimension of guideline quality:

Scope and purpose (three items). This relates to the overall aim of the guideline, the clinical question and the target population it covers.

Stakeholder involvement (four items). This focuses on whether patients and target users of the guideline were involved in its development.

Rigour of development (seven items). This addresses the methods used to search for evidence and formulate recommendations.

Clarity and presentation (four items). This relates to the format and ease of understanding of the guideline.

Applicability (three items). This deals with the potential cost, behavioural and organisational barriers to implementing the guideline.

Editorial independence (two items). This is concerned with the independence of the guidelines from the funding body and acknowledgement of possible conflict of interest in the development group.

Each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 4 ‘Strongly Agree’ to 1 ‘Strongly Disagree,’ with two mid points 3 ‘Agree’ and 2 ‘Disagree.’ Finally, an overall assessment of the quality of the guideline is made, taking each of the appraisal criteria into account, using a four-point categorical scale: ‘Strongly recommend,’ ‘Recommend (with provisos or alterations),’ ‘Would not recommend,’ ‘Unsure.’

Each guideline was anonymised and identified with a unique number. The researcher and two colleagues (a consultant in public health with a background in obstetrics and a research midwife) appraised each guideline independently using the AGREE Instrument as described. Following this independent appraisal, the appraisers met to discuss their scores on items where, for any given guideline, appraisers’ scores differed by at least two points. Where errors or inconsistencies in interpretation of items were identified, scores were revised; these revised scores were used for all analyses. Overall assessments for each guideline were discussed and consensus reached on which guidelines could be recommended for use in practice.

Analysis

In order to assess the presence of response bias, data from the HCC Maternity Services Review on configuration of care within trusts in England and the number of births in the year to 31 March 2007 were used to compare trusts that returned relevant guidelines with those that did not using Fisher exact test and the t test respectively.9

Following the instructions for use of the AGREE Instrument, standardised domain scores for each guideline were calculated by summing the three appraisers’ scores and standardising them as a percentage of the possible maximum score a guideline could achieve for that domain, that is ((obtained score–minimum possible score)/(maximum possible score–minimum possible score))×100. This means that the possible range for standardised domain scores is 0–100%. The instructions for the use of the AGREE Instrument state that domain scores are independent and should not be aggregated to form a single quality score.

Intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated for appraisers’ total scores for each domain to assess inter-rater reliability within each domain. The mean and median domain scores with 95% CI and the proportion of guidelines scoring less than 30%, 30–60% and more than 60% were calculated. Scores for the highest scoring and lowest scoring domains were compared with scores for other domains using the Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank sum test for non-parametric data. The number of births in the trusts producing ‘recommended’ guidelines was compared with the number of births in the other trusts using the t test.

RESULTS

Response and configuration of care

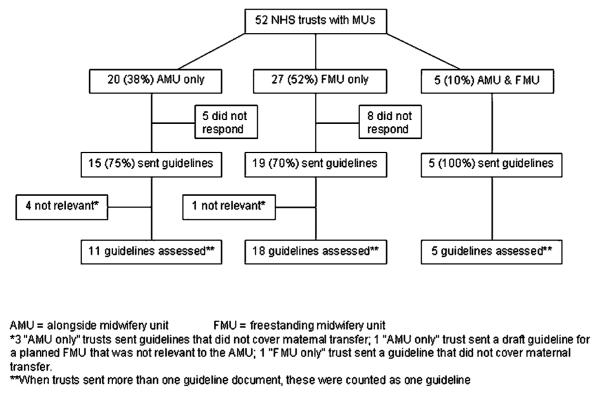

Fifty-two NHS trusts in England were identified as having at least one MU, with 82 MUs identified in all.9 Guidelines were received from 39 (75%) trusts (figure 1). Trusts that had more than one unit all indicated that the same guideline was in use across all units. The guidelines received from five trusts could not be included in the appraisal, as they were not relevant to the topic (see figure 1); guidelines from 34 trusts (65%) were therefore included in the appraisal.

Figure 1.

Configuration of care within NHS trusts with midwifery units (MUs): number of guidelines sent and assessed.

There was no statistically significant difference between responding and non-responding trusts in terms of configuration of care or the number of births (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of responding and non-responding trusts

| Responded n = 34 |

Did not respond n = 18 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration of care n (%) | 0.18* | ||

| AMU only | 11 (55.0) | 9 (45.0) | |

| FMU only | 18 (66.7) | 9 (33.3) | |

| AMU and FMU | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mean (SD) no of births† | 4602 (2251) | 4355 (1710) | 0.69 |

| Range | 282 to 10005 | 2415 to 10140 |

p Value calculated using Fisher exact test as expected cell <5.

No of births in trust in year to 31 March 2007.9

AMU, alongside midwifery unit; FMU, freestanding midwifery unit.

Guideline quality

Intraclass correlation coefficients for the three appraisers showed moderate to good inter-rater reliability for all domains, with best agreement for the ‘stakeholder involvement’ domain (table 2).

Table 2.

Inter-rater reliability for each quality domain* (n=34)

| Domain | Intraclass correlation coefficient† (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Scope and purpose | 0.75 (0.59 to 0.86) |

| Stakeholder involvement | 0.93 (0.86 to 0.96) |

| Rigour of development | 0.84 (0.65 to 0.92) |

| Clarity and presentation | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.78) |

| Applicability | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.79) |

Calculated for only five domains, because all guidelines received minimum possible score from all three raters for domain 6, editorial independence.

Intraclass correlation coefficient calculated using absolute agreement and two-way random effects model.

The mean and median quality scores for the six domains are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Standardised domain scores of all guidelines (n=34)

| Domain | Mean (95% CI) | SD | Median (95% CI) | Range | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope and purpose | 56.2 (48.4 to 64.0) | 22.3 | 59.3 (44.4 to 74.1) | 0–92.6 | 40.7 to 77.8 |

| Stakeholder involvement | 15.3 (9.6 to 20.9) | 16.2 | 9.7 (2.8 to 22.2) | 0–72.2 | 2.8 to 25.0 |

| Rigour of development | 15.0 (9.9 to 20.2) | 14.7 | 9.5 (7.6 to 19.0) | 0–57.1 | 6.3 to 20.6 |

| Clarity and presentation | 45.3 (40.0 to 50.6) | 15.2 | 43.1 (38.9 to 50.0) | 13.9–77.8 | 35.4 to 52.8 |

| Applicability | 7.1 (3.6 to 10.6) | 10.1 | 3.7 (0.0 to 3.7) | 0–37.0 | 0 to 7.4 |

| Editorial independence | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0–0.0 | 0.0 to 0.0 |

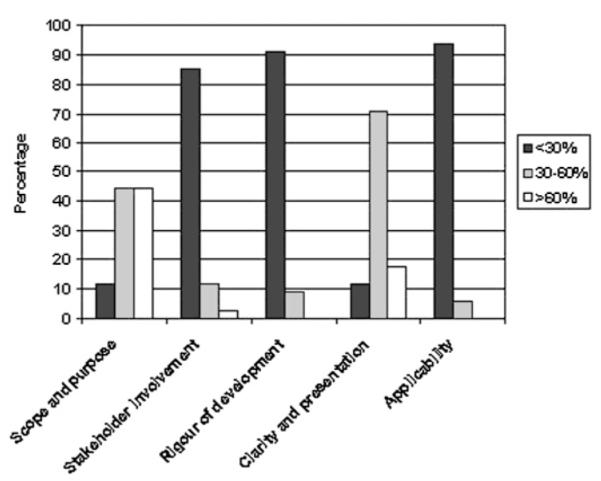

‘Scope and purpose’ scores were statistically significantly higher than scores for the other four domains (p<0.01); 15 of the 34 guidelines (44%) scored more than 60% on this domain (figure 2). In contrast, for the ‘stakeholder involvement’ domain only five guidelines scored more than 30%, and only one scored more than 60%. Two of the guidelines showed evidence that the views of patients had been sought in the development of the guideline, and only one gave any indication of piloting among users. None of the guidelines scored above 60% on ‘rigour of development,’ with all but three scoring less than 30%. For the ‘clarity and presentation’ domain, six of the guidelines scored above 60%, and only four scored less than 30%. ‘Applicability’ scores were significantly lower than for all other domains (p<0.05); none of the guidelines scored above 60% on this domain, and only two scored more than 30%. Only two guidelines gave any indication that the cost implications of applying the recommendations had been considered.

Figure 2.

Percentage of guidelines scoring low, medium and high in five domains of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation instrument.

Overall assessment of quality

Only three of the 34 guidelines assessed were judged by the appraisers to be of sufficient quality to be able to recommend (with provisos or alterations) for use in practice. The three trusts producing these guidelines represented all three types of configuration of care, that is in addition to an obstetric unit one trust had an alongside MU only, one had a freestanding MU only and the third had both types of MU. The trusts producing the recommended guidelines were larger, in terms of number of births per year, than the rest of the sample (mean births/year=7709 vs 4301, p=0.01).

DISCUSSION

This paper reports what we believe to be the first systematic appraisal of the quality of local NHS trust guidelines and focuses on guidelines for the transfer of women from MU to obstetric unit during labour. Most previous studies using the AGREE instrument have focused on the quality of guidelines at national level (eg,11–13), and few have evaluated the quality of local guidelines using this instrument.14 Others evaluating the quality of local guidelines have used methods of documentary analysis15 or have used non-standard quality appraisal tools.16 17

This evaluation was based on guidelines obtained from 34 of the 52 (65%) NHS trusts in England with MUs. Although the initial response rate (75%) was high, the exclusion of some irrelevant guidelines meant that the usable response rate was lower than would be ideal. Data from the HCC Maternity Services Review indicate that all 52 trusts reported having a protocol or guideline covering intrapartum transfer, but we are unable to make any judgements about the quality of guidelines in trusts that did not respond.9 In terms of configuration of care and the number of births in the trust, there was no evidence of systematic differences between trusts that sent relevant guidelines and those that did not, although with the small numbers involved it is difficult to rule out the role of chance with confidence.

Based on their judgements on the overall quality of the guidelines, the three appraisers agreed to recommend (with provisos or alterations) only three of the 34 guidelines evaluated. This is a reflection of the guidelines’ overall poor scoring on four of the six domains. The pattern of scoring across domains, with guidelines scoring reasonably well for ‘scope and purpose’ and ‘clarity and presentation,’ but poorly for ‘stakeholder involvement,’ ‘rigour of development’ and ‘applicability,’ is very similar to that described in another quality appraisal of local guidelines.14 In that study, which evaluated local hospital guidelines for the assessment of suicide attempters in The Netherlands, the ‘editorial independence’ domain, which scores whether conflicts of interest between guideline developers were recorded and whether the guideline was editorially independent from the funding body, was not used, as it was considered irrelevant for the subject. In our study, none of the guidelines scored more than the minimum on this domain, and it could be argued that for an appraisal of guidelines developed at a local level, this domain is not relevant.

Apart from problems with the relevance of the ‘editorial independence’ domain, there were few difficulties with applying the AGREE instrument to these local guidelines. It is a straightforward instrument to use, and comprehensive guidance is provided. All the appraisers were using the instrument for the first time, and while it is not standard practice to revise scores after discussion, this process helped identify and remove scoring errors and inconsistencies in the interpretation of some items, which may not have arisen with appraisers who were more familiar with the instrument. It was apparent that most of the guidelines scored poorly overall. Some guidelines scored well, however, and overall most items were straightforward to apply to the guidelines under scrutiny, suggesting that it is possible and appropriate to use this rigorous instrument on local guidelines.

Overall, the guidelines performed particularly poorly on the two domains that focus most on the methodology of guideline development: ‘rigour of development’ and ‘stakeholder involvement.’ Most contained very little, if any, description of the methodology used for guideline development. Only two of the guidelines showed evidence that the views of patients had been sought in the development of the guideline, and only one gave any indication of piloting among users. Low scores on these domains may, in part, reflect poor reporting of methodology within the guidelines themselves. We were dependent in this appraisal on the information contained within the guidelines and did not explicitly ask for supporting documentation or background information on guideline development, so it is possible that this information was simply missing from the guidelines themselves. However, given the many other differences between low and higher scoring guidelines in terms of style and content, it seems very unlikely that the lower scoring guidelines were developed using a rigorous methodological approach.

This evaluation exposes apparently severe shortcomings in the quality of most of these guidelines evaluated against the stringent criteria set out by the AGREE instrument. It also raises broader questions, however, about the development of clinical guidelines at local level and the approach that the NHS should be taking in the context of limited resources. The better quality guidelines in this study, as judged by the appraisers’ overall recommendations, were developed by larger trusts and broadly in line with the approach advocated by the AGREE collaboration.8 Given their size, these trusts are likely to have more resources to commit to guideline development. In contrast with a mean of over 7000 births per year in these trusts, the smallest trust in this study recorded fewer than 300 births per year.

The development of good-quality guidelines requires specialist skills and significant resources. The perceived benefits of local clinical guidelines include the capacity to reflect local priorities, services and circumstances, and to promote increased local ownership, which may be of importance in terms of effective implementation.18 Some authors have advocated the adaptation of existing guidelines to reflect the local context and circumstances, but this can also be a resource-intensive process.18–20 A framework for a systematic approach for guideline adaptation has been developed by the ADAPTE Collaboration, and work is ongoing to evaluate whether this approach is effective in saving time and resources.21 However, where good-quality national guidelines exist, there is a strong case on the grounds of efficiency and the avoidance of ‘reinventing the wheel’ for resources to be targeted at strategies for the implementation of national guidelines at local level. Within obstetrics, evidence suggests that the most effective strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines involve identifying barriers to change and the use of multifaceted audit and feedback facilitated by local opinion leaders, but it is not clear how widely these strategies are being used within trusts to implement guidelines.22

A challenge remains, however, for those areas where there is little or no national guidance or where national guidelines fall short, such as maternal transfer during labour. In these cases, there may be an argument for a system that could facilitate increased collaboration and sharing of guidelines between trusts. One possible solution could be a central repository for local guidelines, perhaps coordinated by an appropriate royal college or professional body.

This study indicates that further research on the quality of local clinical guidelines is needed in order to evaluate whether the poor methodological quality identified in these midwifery guidelines is replicated in other clinical areas. Initiatives such as the AGREE Collaboration may be seen as having improved the quality of national guidelines. Where appropriate national guidelines exist, there is a strong argument for targeting resources at effective strategies for the implementation of high-quality national guidelines at a local level. In those areas where there may be a continuing need for the development of local clinical guidelines, urgent consideration needs to be given to what is required to ensure that the quality of these guidelines reaches the standards already set, and now widely achieved, for national guidelines.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to M Knight and M Stewart, for their help with appraising the guidelines, C Morris, for advice on calculating intraclass correlation coefficients, F Cluzeau, for information about local guideline development and adaptation, and R Fitzpatrick, J Kurinczuk, R McCandlish and the journal’s reviewers, for their helpful comments on the paper. Thanks are also due to the MUs and hospital trusts, who shared their guidelines with us.

Funding RER is funded by an National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Researcher Development Award. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health, Partnerships for Children, Families and Maternity . Maternity matters: choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service. Department of Health; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit The birthplace in England research programme. Report of component study 1: terms and definitions. [accessed 30 May 2008]. 2007. http://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/birthplace/terms-definitions-report-290307.pdf.

- 3.Stewart M, McCandlish R, Henderson J, et al. Review of evidence about clinical, psychosocial and economic outcomes for women with straightforward pregnancies who plan to give birth in a midwife-led birth centre, and outcomes for their babies. Report of a structured review of birth centre outcomes. Revised 2005. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; Oxford: [accessed 30 May 2008]. 2004. http://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/reports/birth-centre-review.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. National Academy Press; Washington: 1990. p. 38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayward RS, Wilson MC, Tunis SR, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature. VIII. How to use clinical practice guidelines. A. Are the recommendations valid? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;274:570–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.7.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health . Intrapartum care: care of health women and their babies during childbirth. RCOG Press; London: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal College of Midwives, Royal College of Anaesthetists et al. Safer childbirth: minimum standards for the organisation and delivery of care in labour. RCOG Press; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.AGREE Collaboration Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Healthcare Commission Review of maternity services 2007. [accessed 29 April 2008]. 2008. http://www.healthcarecommission.org.uk/healthcareproviders/serviceproviderinformation/reviewsandstudies/servicereviews/ahpmethodolog/maternityservices.cfm.

- 10.The Agree Collaboration . The Appraisal of guidelines for research & evaluation (AGREE) instrument. The Agree Research Trust; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appleyard T, Mann CH, Khan KS. Guidelines for the management of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a systematic appraisal of their quality. BJOG. 2006;113:749–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurdowar A, Graham ID, Bayley M, et al. Quality of stroke rehabilitation clinical practice guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:657–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haagen EC, Hermens RP, Nelen WL, et al. Subfertility guidelines in Europe: the quantity and quality of intrauterine insemination guidelines. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2103–09. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verwey B, van Waarde JA, van Rooij IA, et al. Availability, content and quality of local guidelines for the assessment of suicide attempters in university and general hospitals in the Netherlands. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:336–42. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appleton JV, Cowley S. Analysing clinical practice guidelines. A method of documentary analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:1008–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hindley C, Hinsliff SW, Thomson AM. Developing a tool to appraise fetal monitoring guidelines for women at low obstetric risk. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:307–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hindley C, Hinsliff SW, Thomson AM. English midwives’ views and experiences of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring in women at low obstetric risk: conflicts and compromises. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2006;51:354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchinson A, Feder G. Setting national guidelines in a local context. In: Hutchinson A, Baker R, editors. Making use of guidelines in clinical practice. Radcliffe Medical Press; Abingdon: 1999. pp. 105–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penney G, Foy R. Do clinical guidelines enhance safe practice in obstetrics and gynaecology? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21:657–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voellinger R, Berney A, Baumann P, et al. Major depressive disorder in the general hospital: adaptation of clinical practice guidelines. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:185–93. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ADAPTE, The ADAPTE Collaboration ADAPTE. [accessed 19 August 2008]. 2007. http://www.adapte.org/index.php.

- 22.Chaillet NP, Dube EM, Dugas MM, et al. Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1234–45. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000236434.74160.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]