Abstract

Background

Cholesterol gallstone disease is a complex genetic trait and induced by multiple but as yet unknown genes. A major Lith gene, Lith1 was first identified on chromosome 2 in gallstone-susceptible C57L mice compared with resistant AKR mice. Abcb11, encoding the canalicular bile salt export pump in the hepatocyte, co-localizes with the Lith1 QTL region and its hepatic expression is significantly higher in C57L mice than in AKR mice.

Material and methods

To investigate whether Abcb11 influences cholesterol gallstone formation, we created an Abcb11 transgenic strain on the AKR genetic background and fed these mice with a lithogenic diet for 56 days.

Result

We excluded functionally relevant polymorphisms of the Abcb11 gene and its promoter region between C57L and AKR mice. Overexpression of Abcb11 significantly promoted biliary bile salt secretion and increased circulating bile salt pool size and bile salt-dependent bile flow rate. However, biliary cholesterol and phospholipid secretion, as well as gallbladder size and contractility were comparable in transgenic and wild-type mice. At 56 days on the lithogenic diet, cholesterol saturation indexes of gallbladder biles and gallstone prevalence rates were essentially similar in these two groups of mice.

Conclusion

Overexpression of Abcb11 augments biliary bile salt secretion, but does not affect cholelithogenesis in mice.

Keywords: bile, bile flow, bile salt, biliary secretion, cholesterol saturation index, crystallization, liquid crystals, microscopy, Lith gene

INTRODUCTION

Cholesterol cholelithiasis is one of the most prevalent digestive diseases, resulting in a considerable amount of financial and social burden worldwide [1,2]. Because prevalence of gallstones is rising due to the worldwide obesity epidemic with insulin resistance, a key feature of the metabolic syndrome, it is imperative to investigate cholelithogenesis and find potential ways to prevent the formation of gallstones. Bile formation depends mainly on the sequential action of several membrane lipid transport proteins that are located on the canalicular membrane of the hepatocyte [1–4]. The hepatocyte possesses an ensemble of export pumps belonging to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family of membrane transporters that enable the transport of biliary lipids against their concentration gradients into bile. Alterations in the expression or function of these proteins may affect the lipid compositions of bile and contribute to cholesterol gallstone formation [2–4]. Five major genes encoding ABC transporters involved mainly in bile formation have been cloned and characterized. A major progress in the search for the canalicular lipid transporter comes from the discovery that ABCB4 encodes a phosphatidylcholine transmembrane transporter and there is a lack in hepatic secretion of biliary phosphatidylcholine in Abcb4−/− mice [5,6]. Targeted disruption of Abcb4 induces spontaneous formation of cholesterol gallstones in mice [7], and mutations of ABCB4 result in gallstone formation in humans [8,9]. Moreover, the biochemical and histological characteristics of Abcb4−/− mice closely resemble the corresponding phenotypes of patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC type 3) [10]. Mutations in the genes encoding human ABCG5 and ABCG8 transporters cause sitosterolemia [11,12]. By using transgene techniques, it has been found that overexpression of the human ABCG5/G8 genes in mice markedly alters cholesterol transport in the liver and small intestine: biliary cholesterol secretion and saturation are increased, but fractional absorption of dietary cholesterol is decreased [13]. Furthermore, Abcg5/g8 are mapped to murine chromosome 17 and are candidate genes for the gallstone susceptibility locus Lith9 in the (I/LN×PERA)F2 cross [14]. Furthermore, genome-wide association and family studies have identified the common ABCG8 polymorphism p.D19H as a susceptibility gene for gallstone disease in humans [15,16]. Abcc2 is mapped to chromosome 19 in the mouse and promotes biliary secretion of dianionic xeno- and endobiotics, including glutathione conjugates, bilirubin diglucuronides and bile salts conjugated with sulfate or glucuronide. Thus, ABCC2 may be responsible for the generation of bile salt-independent bile flow, apparently through glutathione secretion. Also, it has been proposed that Abcc2 is a candidate gene for the Lith2 locus [17,18]. The Abcb11 gene encodes a protein called bile salt export pump that transports bile salts from the hepatocyte into bile [19,20] and maps to mouse chromosome 2. In particular, the first quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis of cholesterol gallstones was carried out between inbred strains of gallstone-susceptible C57L and resistant AKR mice [21]. The results from these studies [22,23] showed that Abcb11 co-localized with the Lith1 QTL and its expression in the liver is significantly higher in C57L mice than in AKR mice. Therefore, it has been proposed that Abcb11 is a creedal candidate gene for Lith1 in the C57L strain [22]. In the present study, we created a new Abcb11 transgenic strain (Abcb11.Tg) in the gallstone-resistant AKR genetic background to investigate whether overexpression of the Abcb11 gene in the liver influences cholesterol cholelithogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetically modified mice and diets

Generation of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic mice with overexpression of the Abcb11 gene in a 129S1/SvImJ background has been reported in details in a published paper [24]. Mice were genotyped as described [24], and Southern blot analysis and semiquantitative PCR analysis indicated that these transgenic mice possess two additional intact Abcb11 gene copies. The 129S1 strain shows intermediate susceptibility to gallstone formation in response to the lithogenic diet [25]. It has been suggested that Abcb11 is one of the strongest candidate genes underlying Lith1 in C57L mice, since it co-localizes with the Lith1 QTL [17,22]. To explore whether overexpression of Abcb11 in the liver contributes to gallstone formation, we created a new Abcb11 transgenic strain (Abcb11.Tg) on the gallstone-resistant AKR background by marker-assisted backcrossing [26] of the Abcb11-BAC transgenic strain with the 129S1 background on the AKR background for five generations (N5). These breeding regimen resulted in Abcb11.Tg mice that carry at least 97% AKR genome and ~3% 129S1 genome. Non-transgenic littermates with the same genetic background were used as controls.

Male mice, at 8 to 10 weeks of age, were fed normal mouse chow (Harlan Teklad Laboratory Animal Diets, Madison, WI), or a lithogenic diet containing 1% cholesterol, 0.5% cholic acid and 15% butter fat for 56 days [27]. Mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled room (22±1°C) with a 12-hour day cycle (6 AM-6 PM), and were provided free access to water. All procedures were in accordance with current National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Harvard University.

Microscopic studies of gallbladder biles and gallstones

After cholecystectomy, gallbladder volume was measured by weighing (n=20 per group). Fresh gallbladder bile was examined for mucin gel, solid and liquid crystals, and gallstones, which were defined according to previously established criteria [27]. Pooled gallbladder biles were frozen and stored at −20°C for further lipid analyses.

Hepatic secretion of biliary lipids

After cholecystectomy, the common bile duct was cannulated and hepatic bile was collected by gravity in additional groups of mice (n=5 per group). The first hour collection of hepatic biles was used to study biliary lipid outputs [28]. To determine bile salt-dependent and bile salt-independent bile flow rates, as well as bile salt pool sizes, 8-hour biliary “washout” studies were carried out [28]. During surgery and hepatic bile collection, mouse body temperature was maintained at 37±0.5°C with a heating lamp and monitored with a thermometer.

Lipid analyses

Total and individual bile salt concentrations were measured by reverse-phase HPLC [29]. Biliary phospholipids were determined as inorganic phosphorus by the method of Bartlett [30]. Bile cholesterol, as well as cholesterol content in gallstones and the lithogenic diet were determined by HPLC [27]. Cholesterol saturation indexes (CSI) in pooled gallbladder biles were calculated from the critical tables [31]. Hydrophobicity indexes of bile salts in hepatic biles were calculated according to Heuman’s method [32]. Fecal neutral steroids were saponified, extracted and measured by HPLC [33].

Quantitative real-time PCR assays

Total RNA was extracted from fresh liver tissues (n=4 per group) using RNeasy Midi (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse-transcription reactions were performed using the SuperScript II First-strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 5 μg of total RNA and random hexamers to generate cDNA. Primers and probes for mouse Abca1, Abcb4, Abcg5, Abcg8, Cyp7a1, Hmgcr, Npc1l1, and Srb1 genes have been described elsewhere [34,35]. Real-time PCR assays for all samples were performed in triplicate. To obtain a normalized target level, all values were divided by Gapdh as the invariant control.

Determination of activities of hepatic HMG-CoA reductase and cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase

Fresh liver samples were collected from nonfasted mice (n=5 per group) on chow or fed the lithogenic diet for 56 days. To minimize diurnal variations of hepatic enzyme activities, all procedures were performed between 9:00 and 10:00 AM. Microsomal activities of HMG-CoA reductase were determined by measuring the conversion rate of [14C]HMG-CoA to [14C]mevalonic acid and with [3H]mevalonolactone as internal standard [36]. Hepatic activities of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase were determined by HPLC as described elsewhere [36].

Gallbladder contraction study

To explore whether gallbladder emptying was altered during the lithogenic diet feeding, we measured gallbladder contraction function in response to exogenously administered cholecystokinin (CCK) (17 nmol/kg body weight) or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution as a control in Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice (n=5 per group) on chow (day 0) and at 56 days on the lithogenic diet [35]. Gallbladder contractile function was determined by comparing bile flow rates and bile salt concentrations in the collected hepatic bile samples before and after the IV administration of CCK-8 [35].

Measurement of intestinal cholesterol absorption

(i) Fecal dual-isotope ratio method. Nonfasted and non-anesthetized mice (n=5 per group) were given by gavage an intragastric bolus of 1 μCi of [14C]cholesterol and 2 μCi of [3H]sitostanol mixed with 150 μl of medium-chain triglyceride. To calculate the percent cholesterol absorption, the ratios of the two radiolabels in the fecal extract from the 4-day pooled feces and the dosing mixture were assayed, respectively [33,37]. (ii) Plasma dual-isotope ratio method. Additional groups of chow-fed mice (n=5 per group) were injected intravenously with 100 μl of Intralipid containing 2.5 μCi of [3H]cholesterol. Immediately, each animal was given by gavage an intragastric bolus of 150 μl of medium-chain triglyceride containing 1 μCi of [14C]cholesterol. The ratio of the two radiolabels in the plasma sample taken on the third day was used for calculating the percent cholesterol absorption [33,37].

Cholesterol balance analysis

Mice housed in individual metabolic cages with wire mesh bottoms were allowed to adapt to the environment for 2 weeks. When body weight, food ingestion, and fecal excretion were constant, indicating an apparent metabolic steady state, food intake was measured and feces were collected daily for the balance study. The mice (n=5 per group) were fed the lithogenic diet for 7 days. Then, cholecystectomy was performed and the common bile duct was cannulated and hepatic bile was collected for the first hour of biliary secretion. Percent cholesterol absorption was calculated as described previously [33].

Comparative sequencing of mouse Abcb11 cDNA and promoter sequences

cDNA from strains AKR and C57L was obtained by reverse-transcription-PCR (Superscript, Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) from RNA isolated from liver, using Ultraspec reagent (Biotecx, TX). All Abcb11 exons were amplified with 20 ng DNA, 100 nM primers (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany), 20 mM TRIS/HCl, pH 8.55, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.6 mM (NH4) 2SO4, 50 μM dNTPs, 0.4 U Taq polymerase (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) in 20 μl reaction volume; 95°C/5 min, 95°C/1 min, −55°C/30 sec, −72°C 1 min (35 cycles), and 72°C/7 min).

Promoter sequence (−1,785 bp) from the strain C57L (GenBank Accession No. AF303740) was generated by Genome Walking (Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany), using gene specific primers 5′-ttgaagtgacccttgtgacatcctg-3′ and 5′-cttctgctcagaactctgtgcacac-3′. Additional promoter sequence (−5,485 bp) was obtained by direct sequencing of BAC clone RP23-291P1 [24] (Trans NIH Mouse Initiative). The open reading frame of the Abcb11 cDNA (4,866 bp) and promoter sequences (5,485 bp) were compared between strains AKR and C57L by direct sequencing of PCR products [38]. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Potential transcription factor bindings sites were identified using MatInspector 2.2 based on the Transfac Database 4.0 (Genomatix Software, München, Germany). Dual luciferase reporter gene assays using vectors pGL3b and pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI) and cotransfection with expression vectors hFXR and hRXR (kindly provided by Dr. David Mangelsdorf, Dallas, TX) were carried out as described [39].

Statistical methods

All data are expressed as means±SD. Statistically significant differences among groups of mice were assessed by Student’s t-test or Chi-square test. By linear regression analyses, parameters significantly associated with bile flow rates and bile salt secretion rates were further assessed by a stepwise multiple regression analysis to identify the independence of the association. Analyses were performed with SuperANOVA software. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed probability of less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of Abcb11 overexpression on biliary secretion

As shown in Table 1, mean bile flow rates following acute (first hour) interruption of the enterohepatic circulation are significantly higher in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice on chow or fed the lithogenic diet. On chow, hepatic outputs of biliary cholesterol and phospholipid were essentially similar between Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice. Compared with the chow diet, feeding the lithogenic diet significantly increased secretion rates of biliary cholesterol and phospholipids; however, no significant differences in these secretion rates existed between Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice. In contrast, bile salt outputs were significantly higher in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice, regardless of whether chow or the lithogenic diet was fed. Furthermore, we used biliary “washout” techniques to measure the circulating bile salt pool sizes, which were significantly larger in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice. Moreover, the total bile salt pool sizes, i.e., the circulating bile salt pool size plus the bile salt pool in the gallbladder, were still markedly larger in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice. Furthermore, we found that under basal physiological conditions (on chow, day 0), the relative mRNA levels for the hepatic lipid transporters Abcb4, Abcg5, and Abcg8 were essentially similar in both groups of mice. In the lithogenic state, there was a 4-fold increase (P<0.05) in gene expression levels of all these transporters (data not shown). However, no significant statistical differences in their relative mRNA levels were found between Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice.

Table 1.

Bile flow rates, biliary lipid outputs, as well as bile salt pool sizes and species

| Parameter | Wild-type | Abcb11.Tg |

|---|---|---|

| Chow diet | ||

| Bile flow (μl/min/kg) | 49.7±2.7 | 72.2±10.8A |

| Biliary output | ||

| Cholesterol (μmol/h/kg) | 6.0±1.3 | 6.1±1.1 |

| Phospholipid (μmol/h/kg) | 17.0±2.4 | 20.5±1.9 |

| Bile salt (μmol/h/kg) | 105.3±13.4 | 134.5±15.1A |

| Circulating bile salt pool size (μmol) | 5.6±0.5 | 6.1±0.7 |

| Total bile salt pool size (μmol) | 9.9 | 10.8 |

| Bile salt species | ||

| Taurocholate | 49.7±6.7 | 51.4±8.0 |

| Tauro-β-muricholate | 42.2±5.6 | 43.6±7.2 |

| Taurochenodeoxycholate | 0.6±0.3 | 0.5±0.2 |

| Tauro-ω-muricholate | 1.4±0.6 | 1.3±0.7 |

| Tauroursodeoxycholate | 2.6±1.6 | 2.1±0.6 |

| Taurodeoxycholate | 3.4±1.3 | 1.1±0.5 |

| Hydrophobicity index | −0.33±0.05 | −0.35±0.06 |

| Lithogenic diet | ||

| Bile flow (μl/min/kg) | 56.9±7.0 | 75.7±12.4B |

| Biliary output | ||

| Cholesterol (μmol/h/kg) | 9.5±1.1A | 10.2±3.3C |

| Phospholipid (μmol/h/kg) | 35.7±11.6A | 45.0±15.6C |

| Bile salt (μmol/h/kg) | 115.0±20.1 | 152.9±28.8B |

| Circulating bile salt pool size (μmol) | 5.3±0.8 | 7.0±1.2B |

| Total bile salt pool size (μmol) | 11.4 | 14.1 |

| Bile salt species | ||

| Taurocholate | 74.3±7.3A | 69.6±4.0C |

| Tauro-β-muricholate | 2.9±0.2A | 3.1±1.5C |

| Taurochenodeoxycholate | 11.1±3.4A | 13.4±0.9C |

| Tauro-ω-muricholate | 1.7±0.4 | 2.6±1.9 |

| Tauroursodeoxycholate | 3.2±1.0 | 2.4±0.7 |

| Taurodeoxycholate | 6.9±3.3A | 9.0±1.3C |

| Hydrophobicity index | 0.04±0.03A | 0.06±0.02C |

Values represent mean±SD of five mice per group. All mice were fed normal rodent chow containing trace (<0.02%) amounts of cholesterol at day 0, or the lithogenic diet containing 1% cholesterol, 0.5% cholic acid and 15% butter fat for 56 days.

P<0.05, compared with wild-type mice on the chow diet;

P<0.05, compared with wild-type mice on the lithogenic diet;

P<0.05, compared with Abcb11.Tg mice on the chow diet.

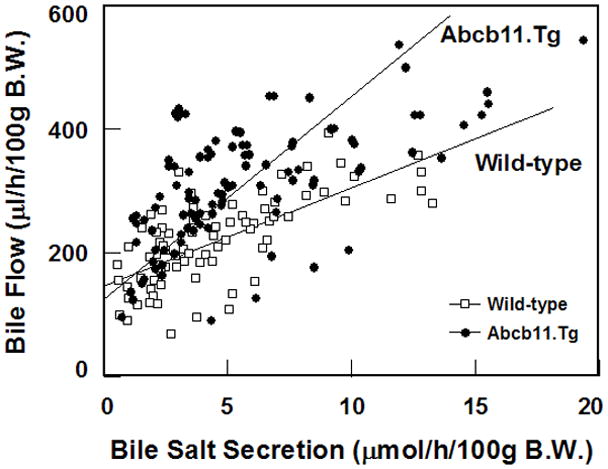

Figure 1 displays the relationships of bile flow to bile salt secretion rates from the “washout” data demonstrating combined hepatic bile data in both strains on chow and fed the lithogenic diet. The slope of the lines represents the relationships between bile flow and bile salt output that defines bile salt-dependent bile flow. Its intercept with the ordinate axis estimates the bile salt-independent bile flow. When the data were analyzed with a conventional regression line, the slopes were significantly different. They were 33±3 μl (bile H2O)/μmol bile salts for Abcb11.Tg mice, being significantly greater (P<0.001) than those (16±2 μl/μmol) for wild-type mice. However, the extrapolated y-intercepts of the regressions displayed similar values between Abcb11.Tg (120±15μl/h/100g) and wild-type mice (146±10μl/h/100g), indicating that the bile salt-independent bile flow was essentially similar in these two groups of mice.

Figure 1.

Bile flow as a function of bile salt output in mice before (on chow, day 0) and at 56 days on the lithogenic diet. Each point represents bile flow and bile salt output measurements in the same sample during 8-hour periods of biliary “washout”. Bile salt-dependent bile flow in Abcb11.Tg mice is significantly (P<0.001) greater than that in wild-type mice. Equations for canalicular bile salt-dependent flow are y=120(±15)+33(±3)x (r=0.66; P<0.001) for Abcb11.Tg mice and y=146(±10)+16(±2)x (r=0.70; P<0.001) for wild-type mice. Upon extrapolation of the regression lines to the ordinate, the y-intercepts are similar in these two groups of mice, suggesting that bile salt-independent flow is similar between Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice.

Consistent with previous studies [27,28], analysis of individual bile salts by HPLC revealed that all were taurine conjugated. On chow, Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice displayed identical distributions of bile salt species in hepatic biles, with taurocholate and tauro-β-muricholate being the predominant bile salts and others being present in smaller concentrations (Table 1). In the lithogenic state, taurocholate was significantly increased, but tauro-β-muricholate was significantly decreased, most contributable to cholic acid in the lithogenic diet. In addition, both taurochenodeoxycholate and taurodeoxycholate were significantly increased. However, tauro-ω-muricholate and tauroursodeoxycholate remained unchanged. Again, no differences in the distributions of bile salt species were found in both strains of mice. Of note, the changes of bile salt compositions in gallbladder biles (data not shown) were similar to those in hepatic biles (Table 1).

Effects of Abcb11 overexpression on gallstone formation

On chow, the gallbladder wall was thin and transparent. Macroscopic and light microscopic examination of gallbladder biles showed no evidence of mucin gel, solid and liquid crystals, or gallstones. At 56 days on the lithogenic diet, gallstone prevalence rates were essentially similar in these two strains of mice, with 25% of Abcb11.Tg mice and 20% of wild-type mice forming gallstones. The cholesterol extracted from these stones constituted >99% of stone weight. Moreover, gallstone diameters were similar between Abcb11.Tg mice (0.32±0.14 mm) and wild-type mice (0.24±0.13 mm). It should be emphasized that 75% of Abcb11.Tg mice and 80% of wild-type mice were gallstone free; however, most of these mice contained a thin layer of mucin gel, as well as some solid and liquid crystals.

Lipid compositions of pooled gallbladder and individual hepatic biles

Table 2 shows biliary lipid compositions of pooled gallbladder biles (n=20 per group). On chow, Abcb11.Tg mice displayed slightly higher mole percent cholesterol (=2.18%) and cholesterol saturation index (CSI=0.45) compared with wild-type mice (mole percent cholesterol=1.73% and CSI=0.35, respectively). However, at 56 days on the lithogenic diet, gallbladder biles became supersaturated with cholesterol, as well as mole percent cholesterol and CSIs reached essentially similar values between two strains of mice. Furthermore, the biles of Abcb11.Tg mice contained identical mole percent phospholipid and bile salts compared with wild-type mice.

Table 2.

Biliary lipid compositions of pooled gallbladder and individual hepatic bilesA

| Mouse | Mole%ChB | Mole%PL | Mole%BS | PL/(PL+BS) | [TL] (g/dl) | CSIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chow diet | ||||||

| Pooled gallbladder biles | ||||||

| Wild-type | 1.73 | 13.28 | 85.00 | 0.14 | 10.14 | 0.35 |

| Abcb11.Tg | 2.18 | 12.77 | 85.04 | 0.13 | 10.76 | 0.45 |

| Individual hepatic biles | ||||||

| Wild-type | 4.75±0.96 | 14.19±3.45 | 81.06±4.38 | 0.15±0.04 | 2.33±0.28 | 1.23±0.10 |

| Abcb11.Tg | 4.05±0.72 | 12.80±2.02 | 83.15±2.43 | 0.13±0.02 | 1.98±0.30 | 1.19±0.16 |

| Lithogenic diet | ||||||

| Pooled gallbladder biles | ||||||

| Wild-type | 9.23 | 22.08 | 68.69 | 0.24 | 13.83 | 1.20 |

| Abcb11.Tg | 9.71 | 21.75 | 68.54 | 0.24 | 14.80 | 1.26 |

| Individual hepatic biles | ||||||

| Wild-type | 6.76±1.05 | 20.94±5.09 | 72.31±5.77 | 0.22±0.06 | 2.55±0.47 | 1.29±0.16 |

| Abcb11.Tg | 7.10±0.68 | 21.35±4.22 | 71.55±4.53 | 0.23±0.05 | 2.57±0.29 | 1.33±0.15 |

Values were measured from pooled gallbladder biles (n=20 per group) and individual hepatic biles (n=5 per group).

Abbreviations: Ch, cholesterol; PL, phospholipid; BS, bile salt; [TL], total lipid concentration; CSI, cholesterol saturation index.

The CSI values of pooled gallbladder and six hepatic biles were calculated from the critical tables [31].

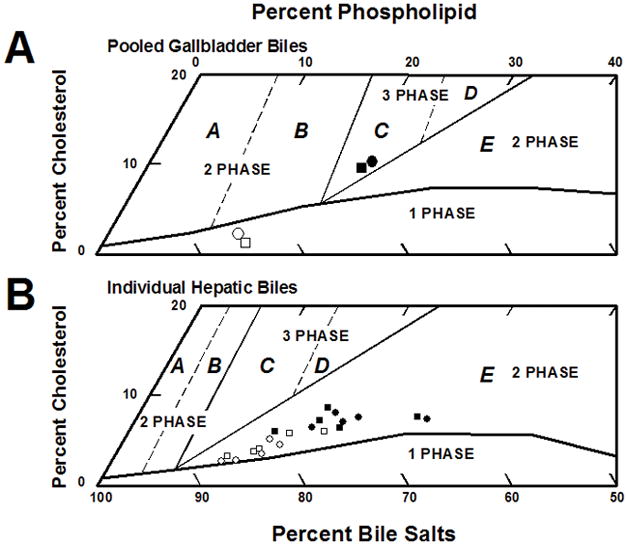

Table 2 also lists the biliary lipid compositions of individual hepatic biles from Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice during the first hour of interrupted enterohepatic circulation while on chow and on the lithogenic diet for 56 days. As discussed elsewhere [40], if these biles were at equilibrium, they would be composed of liquid crystals and saturated micelles but never solid crystals. We occasionally detected sparse numbers of small liquid crystals in fresh hepatic bile samples under microscopic examination (×800 magnification), and when observed over several days, these biles never formed solid cholesterol monohydrate crystals. This is in complete agreement with equilibrium two-phase nature of region E [40], as shown in Figure 2. Moreover, the relative lipid compositions of pooled gallbladder biles in both groups of mice were located in region C of the central three-phase zone in which biles are composed of cholesterol monohydrate crystals, liquid crystals and saturated micelles at equilibrium [40].

Figure 2.

(A) Relative lipid compositions of pooled gallbladder biles (n=20 per group) plotted on a condensed phase diagram according to average total lipid concentration (10.0 g/dl) of biles (see Table 2). One-phase micellar zone is enclosed by solid curved line. Above the micellar zone, two solid and two dashed lines divide the phase diagram into regions A to E with different crystallization sequences [40]. Relative lipid compositions of pooled biles from chow-fed Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice are located in one-phase micellar zone. Upon challenge to the lithogenic diet, lipid compositions of pooled gallbladder biles from these mice plot in central three-phase zone, where at equilibrium biles would be composed of cholesterol-saturated micelles, solid cholesterol crystals, and liquid crystals. (B) Lipid compositions of individual hepatic biles (n=5 per group) are plotted on a condensed phase diagram for average total lipid compositions (2.5 g/dl) of biles (see Table 2). This system exhibits the same physical states at equilibrium as for gallbladder biles, but all crystallization pathways are shifted to the left with decreases in total lipid concentration [40]. These changes generate a new condensed phase diagram with smaller one-phase micellar zone and enlarged region E. Relative lipid compositions of all hepatic biles locate in region E, where at theoretical equilibrium biles would be composed of liquid crystals and saturated micelles but not solid cholesterol crystals. In this work, fresh hepatic biles of all mice are generally clear microscopically, suggesting their nonequilibrium nature. Symbols (white for the chow diet; black for the lithogenic diet): ○/● Abcb11.Tg mice; □/▪ wild-type mice.

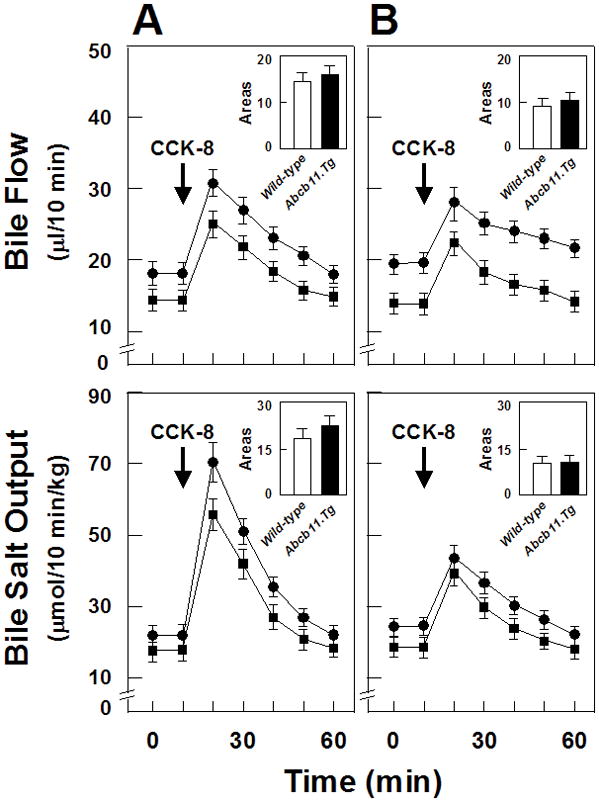

Gallbladder volumes and emptying

On chow, gallbladder volumes were similar between Abcb11.Tg mice (15±7 μl) and wild-type mice (13±6 μl). In the lithogenic state, gallbladder sizes (25±9 μl) were enlarged in these mice while cholesterol crystallization and gallstones were developed. Figure 3 shows gallbladder emptying function as indicated by changes in bile flow rates (top panels) and biliary bile salt outputs (bottom panels) stimulated by IV injection of CCK-8 (as shown by arrows) in mice on chow or fed the lithogenic diet. As shown in Figure 3A (on chow, day 0), because of gallbladder emptying, bile flow rates and biliary bile salt outputs were increased sharply and significantly by exogenously administered CCK-8 and these parameters were comparable in Abcb11.Tg mice vs. wild-type mice. In the lithogenic state (Figure 3B), bile flow rates and biliary bile salt outputs were increased slightly by CCK-8 in both strains of mice. These alterations suggest that gallbladder contractile function is impaired partially in both strains of mice at 56 days on the lithogenic diet compared with those on the chow diet. Again, gallbladder contractility in response to CCK-8 was comparable in Abcb11.Tg mice vs. wild-type mice. As expected, PBS administration (data not shown) did not influence gallbladder sizes in either group.

Figure 3.

Gallbladder emptying function as shown by changes in bile flow rates and biliary bile salt outputs stimulated by IV injection of CCK-8 in Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice (A) on chow or (B) fed the lithogenic diet. Because of gallbladder emptying, bile flow rates and biliary bile salt outputs are increased sharply and significantly by exogenously administered CCK-8 (as indicated by the arrows). Although gallbladder contractility is impaired partially in the lithogenic state compared with the chow diet, no differences in these parameters are found in both groups of mice. Symbol ● represents Abcb11.Tg mice and ▪ wild-type mice.

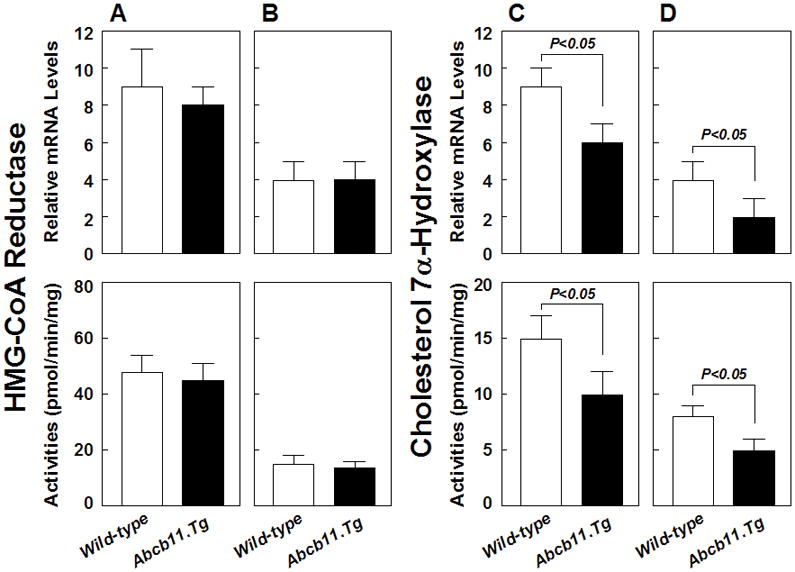

Hepatic cholesterol and bile salt synthesis

Of special note is that mRNA levels and enzymatic activities of hepatic HMG-CoA reductase were comparable in Abcb11.Tg mice vs. wild-type mice, regardless of whether (Figure 4A) chow or (Figure 4B) the lithogenic diet is fed. Noticeably, the lithogenic diet significantly reduced expression levels and activities of hepatic HMG-CoA reductase in these mice. Furthermore, on chow (Figure 4C), expression levels and enzymatic activities of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase in the liver were significantly lower in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice. Feeding the lithogenic diet reduced enzymatic activities and gene expression levels for hepatic bile salt synthesis in both groups of mice (Figure 4D). However, Abcb11.Tg mice still showed significantly lower gene expression levels and enzymatic activities of hepatic cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase compared with those in wild-type mice.

Figure 4.

Gene expression levels and enzymatic activities of HMG-CoA reductase and cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase in livers of Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice (n=5 per group). mRNA levels and activities of HMG-CoA reductase are essentially similar in these mice, regardless of whether (A) the chow or (B) the lithogenic diet is fed. Obviously, mRNA levels and activities of HMG-CoA reductase are significantly (P<0.01) reduced under high dietary cholesterol loads. Compared with (C) the chow diet, (D) feeding the lithogenic diet significantly reduces mRNA levels and enzymatic activities of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase in all mice. Of note is that mRNA levels and enzymatic activities are significantly lower in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice.

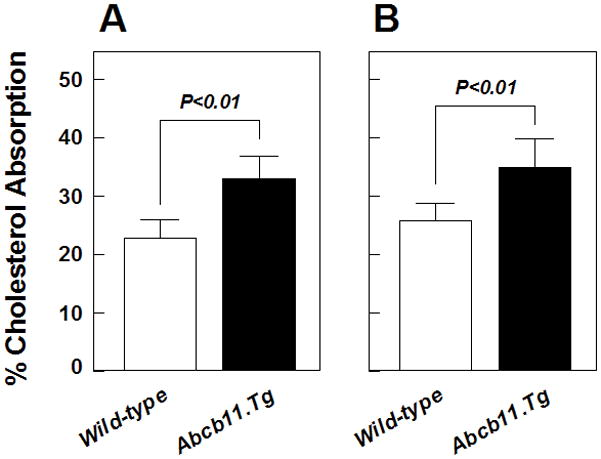

Effects of Abcb11 overexpression on intestinal cholesterol absorption

On chow, cholesterol absorption efficiency was significantly higher in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice as measured by two independent techniques, the plasma (Figure 5A) and the fecal dual-isotope ratio methods (Figure 5B). Because high dietary cholesterol exerts the effect of radioisotope dilution on the specific activity of cholesterol in the upper small intestine, we used cholesterol balance analysis to determine cholesterol absorption efficiency in mice challenged with the lithogenic diet. Cholesterol absorption efficiency measured by the mass balance method was significantly increased to 35±4% in wild-type mice mice and to 47±4% in Abcb11.Tg mice (P<0.01, compared with wild-type mice) in challenge to the lithogenic diet, because of the dietary cholic acid [33]. These results suggest that, regardless of whether chow or the lithogenic diet was fed, increased hepatic outputs of biliary bile salts and larger circulating bile salt pool sizes in Abcb11.Tg mice greatly enhance intestinal cholesterol absorption, mostly because these alterations resulted in more cholesterol dissolved in micelles within the small intestinal lumen.

Figure 5.

Effects of Abcb11 overexpression on intestinal cholesterol absorption. Cholesterol absorption efficiency was determined by (A) the plasma and (B) the fecal dual-isotope ratio methods in chow-fed mice (n=5 per group). As measured by the plasma and the fecal dual-isotope ratio methods, intestinal cholesterol absorption is significantly increased in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice. No differences in percent cholesterol absorption are found by two independent methods.

Of note is that relative mRNA levels of the intestinal Npc1l1 gene in chow-fed Abcb11.Tg mice were 3-fold higher (P<0.05) than those in wild-type mice. In contrast, no significant differences in expression levels of Abca1, Abcg5, Abcg8, and Srb1 in the small intestine were found between two groups of mice (data not shown).

Comparative sequencing of the mouse Abcb11 in strains AKR and C57L and reporter gene assays

Sequencing of cDNAs, representing all 28 Abcb11 exons, and the 5′-flanking regions (see Methods) revealed no differences between strains AKR and C57L, except for a C/T-transition at position −3,757 in the strain C57L. This transition is localized in an Lx8 repeat element, which represents a long interspersed repeat (LINE) 1 fragment that might have regulatory functions [41,42]. Albeit no potential transcription factor binding sites were identified in the Lx8 repeat element, we performed additional luciferase assays. We cloned the sequences of both mouse strains (−4,050/−3,561 bp) in front of the Abcb11 minimal promoter (−376/+64 bp). This led to a significant (P<0.01) reduction of promoter activity from 0.32±0.05 to 0.17±0.01 RLU, but no differences were observed between constructs harboring sequences from strains C57L and AKR.

DISCUSSION

Cholesterol cholelithiasis, similar to most common diseases such as atherosclerosis and obesity, is a complex trait and does not qualify readily to simple Mendelian analysis for single-gene traits [3,4]. A powerful genetic technique, QTL analysis provides a crucial method for identifying, locating and estimating the lithogenic effects of genes that underlie complex traits in inbred mice challenged to the lithogenic diet. The mouse model of cholesterol gallstones is an important experimental system for identifying pathophysiologically relevant Lith QTL as well as finding candidate Lith genes and the biochemical and physiological pathways for this complex disease. A genome-wide search was first applied to the AKR and C57L inbred strains for genetic analysis of cholesterol gallstones [21]. After AKR, C57L and (AKR×C57L)F1 mice were fed with the lithogenic diet for 56 days, it was found that cholesterol gallstone formation is a dominant trait because the F1 mice have gallstones of similar prevalence and weight to the C57L parental strain [27]. The first gallstone QTL locus was mapped to chromosome 2 and named Lith1 [17,21,22]. Subsequently, the second locus Lith2 was localized on chromosome 19 [17,18,21]. Each QTL has been confirmed to have a strong, independentimpact on gallstone risk as shown by two congenic strains: onewith the C57L allele at the Lith1 locus, and the other with the C57L allele at the Lith2 locus introgressed into the AKR background [17].

Since the Lith1 locus was identified, the cholesterol gallstone phenotypes in C57L and AKR strains and their F1 progeny were systematically characterized. Compared with AKR mice, C57L mice display higher hepatic secretion of biliary cholesterol and bile salts, bile salt-dependent bile flow, and CSIs, as well as larger gallbladders, greater accumulationof gallbladder mucin gel, and gallbladder hypomotility [27,28]. Also, C57L mice show significantly higher hepatic HMG-CoA reductase activities for cholesterol biosynthesis and relatively lower activities of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase and sterol 27-hydroxylase for bile salt synthesis than AKR mice [33].

The Lith1 QTL that was identified in previousstudies [21] showed peak linkage to markers D2Mit11 (71.7 Mb) and D2Mit66 (84.7 Mb). Subsequently, Lith1 was confirmed using additional backcrosses with congenic mice and refined to the interval between D2Mit182 (68.8 Mb) and D2Mit11 (71.6 Mb) [17,43]. However, this region still encompasses many genes, some of which are related to lipid metabolism and transport. For example, the Lrp2 gene encoding the LDL-receptor-related protein 2, previously known as megalin (Gp330), a member of the LDL receptor gene family, maps to the Lith1 region. LRP2 is expressed in gallbladder epithelium and regulated by bile acids [44]; however, it is not expressed in the hepatocyte and appears not to have major effects on biliary lipid secretion as well as hepatic lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Another candidate for Lith1 is Abcb11, a gene encoding an ABC transporter, previously known as bile salt export pump (Bsep) or sister to P-glycoprotein (Spgp) [19,20]. This protein is expressed on the canalicular membrane of hepatocytes and transports bile salts into the canalicular bile [19,20,23]. Indeed, compared with AKR mice, C57L mice display significantly higher expression levels of Abcb11 in the hepatocyte as well as hypersecretion of biliary bile salts and cholesterol [22,23,28].

In the present study, we observed that overexpression of Abcb11 promotes hepatic secretion of biliary bile salts and increases circulating bile salt pool sizes as well as bile salt-dependent bile flow rates. However, mice overexpressing the Abcb11 gene show essentially similar secretion rates of biliary cholesterol compared with AKR mice, and the Abcb11 overexpression does not influence cholesterol cholelithogenesis in mice challenged to the lithogenic diet. Henkel et al. [45] developed TTR-Abcb11 transgenic mice in the FVB/NJ genetic background and reported that cholesterol gallstone prevalence was increased in mice overexpressing Abcb11 upon feeding the lithogenic diet. It has been found [24] that overexpression of the Abcb11 gene in TTR-Abcb11 transgenic mice increases biliary secretion of not only bile salts, but also cholesterol and phospholipids. Of note is that TTR-Abcb11 transgenic mice were created in the FVB/NJ background. Since FVB/NJ mice are a gallstone-susceptible inbred strain, it could not be excluded that rapid gallstone formation is conferred by other Lith genes. In the present study, we developed a new Abcb11 transgenic strain in the gallstone-resistant AKR genetic background, demonstrating that the murine strain background markedly influences the phenotype of transgenic mice overexpressing Abcb11. We observed that compared with wild-type mice, Abcb11.Tg mice secrete an essentially similar amount of cholesterol and a larger amount of bile salts in relation to phospholipid, even in the lithogenic state. One possible explanation is that the lack of lithogenic effects in the present study is due to the increased bile flow, which decreases the relative concentration of bile salts in the canalicular space. Apparently, the increased bile salt secretion could just compensate for this effect, resulting in an essentially identical canalicular bile salt concentration in Abcb11.Tg vs. wild-type mice. Therefore, our results indicate that the Abcb11 overexpression does neither induce relative nor absolute biliary cholesterol hypersecretion for the formation of lithogenic hepatic bile. As a result, no differences in gallstone formation are found in these two groups of mice. Since the phenotypes of gallbladder and hepatic biles in Abcb11.Tg mice mimic the gallstone-resistant AKR strain, these observations do not support the notion that the Abcb11 gene underlies Lith1. Furthermore, we found that neither polymorphisms in the Abcb11 gene nor functionally relevant promoter variants exist between strains C57L and AKR. In addition, Schafmayer et al. did not find evidence of association of the ABCB11 gene to gallstone susceptibility in a Caucasian population, suggesting that systematic fine mapping of the Lith1 region is required to identify the causative genetic variants for gallstones [46,47].

Using biliary “washout” techniques, we measured the circulating bile salt pool sizes and observed that the pool sizes are significantly enlarged in mice overexpressing Abcb11. This is mainly contributed to increased hepatic secretion of biliary bile salts in the transgenic mice. Canalicular bile formation has been traditionally divided into two components: bile salt-dependent flow, defined as the slope of the line relating canalicular bile flow to bile salt output, and bile salt-independent flow, attributed to the active secretion of inorganic electrolytes and other solutes, and defined as the extrapolated y-intercept of this line. Our results reveal that bile salt-dependent flow is significantly greater in Abcb11.Tg mice than in wild-type mice, mainly due to biliary bile salt hypersecretion induced by overexpression of the hepatic Abcb11 gene. In contrast, bile salt-independent flow is similar in these two groups of mice. Moreover, because augmented biliary bile salt outputs enhance micellar cholesterol solubilization, intestinal cholesterol absorption efficiency is significantly increased in mice overexpressing Abcb11. This result is consistent with the striking induction of Npc1l1 expression in the intestine of Abcb11.Tg mice.

In our phenotypic study of the rate-limiting enzymes for bile salt syntheses, we observed that compared with wild-type mice, Abcb11.Tg mice display significantly lower mRNA levels and enzymatic activities of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase. It probably relates to larger circulating bile salt pool size in the transgenic mice, which could result in increased enterohepatic return of bile salts to the liver. Also, intestinal FXR stimulated by enlarged circulating bile salt pool size could increase expression of fibroblast growth factor-19 (FGF-19), a secreted growth factor that signals through the FGFR4 cell-surface receptor tyrosine kinase. In turn, FGF-19 might reduce expression of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase in the liver through c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) or extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2)-dependent pathways in Abcb11.Tg mice [48,49]. Furthermore, mRNA levels and enzymatic activities of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase are reduced in all mice in response to the lithogenic diet, mostly due to the presence of 0.5% cholic acid in the diet. In contrast, no differences in mRNA levels and enzymatic activities of HMG-CoA reductase are found between Abcb11.Tg and wild-type mice, consistent with identical hepatic secretion of biliary cholesterol in these mice.

In summary, the pathophysiological phenotypes of the Abcb11 gene as inferred from comprehensive biliary lipid secretion and gallstone studies in Abcb11.Tg mice suggest that an increased hepatic secretion of biliary bile salts is not a major factor for the development of supersaturated bile and the formation of cholesterol gallstones in mice. The present results support the notion that the Abcb11 overexpression enhances hepatic secretion of biliary bile salts, enlarges the circulating bile salt pool size, and induces higher bile salt-dependent bile flow. Our work offers a critical clue for positional cloning of Lith1, as well as a basic framework for further investigating how individual Lith genes promote biliary cholesterol secretion and enhance cholesterol cholelithogenesis in mice. Furthermore, because of the homology of human and mouse chromosomes, it is possible to identify human Lith genes from mouse studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by research grants DK54012 and DK73917 (to D.Q.-H.W.) from the National Institutes of Health (US Public Health Service), by the Trans-NIH Mouse Initiative (to F.L.), and by a research grant DFG 997/3-1 (to F.L.) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Germany).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette (transporter)

- BAC

bacterial artificial chromosome

- CCK-8

sulfated cholecystokinin octapeptide

- CSI

cholesterol saturation index

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A

- QTL

quantitativetrait locus

References

- 1.Wang DQ-H, Cohen DE, Carey MC. Biliary lipids and cholesterol gallstone disease. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 (Suppl):S406–411. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800075-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet. 2006;368:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammert F, Carey MC, Paigen B. Chromosomal organization of candidate genes involved in cholesterol gallstone formation: a murine gallstone map. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:221–238. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang DQ-H, Afdhal NH. Genetic analysis of cholesterol gallstone formation: searching for Lith (gallstone) genes. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:140–150. doi: 10.1007/s11894-004-0042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, Oude Elferink RP, Groen AK, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, et al. Homozygous disruption of the murine mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene leads to a complete absence of phospholipid from bile and to liver disease. Cell. 1993;75:451–462. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oude Elferink RP, Ottenhoff R, van Wijland M, Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, Groen AK. Regulation of biliary lipid secretion by mdr2 P-glycoprotein in the mouse. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:31–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI117658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lammert F, Wang DQ-H, Hillebrandt S, Geier A, Fickert P, Trauner M, et al. Spontaneous cholecysto- and hepatolithiasis in Mdr2−/− mice: a model for low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis. Hepatology. 2004;39:117–128. doi: 10.1002/hep.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosmorduc O, Hermelin B, Boelle PY, Parc R, Taboury J, Poupon R. ABCB4 gene mutation-associated cholelithiasis in adults. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:452–459. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00898-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosmorduc O, Hermelin B, Poupon R. MDR3 gene defect in adults with symptomatic intrahepatic and gallbladder cholesterol cholelithiasis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1459–1467. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strautnieks SS, Bull LN, Knisely AS, Kocoshis SA, Dahl N, Arnell H, et al. A gene encoding a liver-specific ABC transporter is mutated in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Nat Genet. 1998;20:233–238. doi: 10.1038/3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, Schultz J, et al. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290:1771–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MH, Lu K, Hazard S, Yu H, Shulenin S, Hidaka H, et al. Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nat Genet. 2001;27:79–83. doi: 10.1038/83799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu L, Li-Hawkins J, Hammer RE, Berge KE, Horton JD, Cohen JC, et al. Overexpression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 promotes biliary cholesterol secretion and reduces fractional absorption of dietary cholesterol. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:671–680. doi: 10.1172/JCI16001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wittenburg H, Lyons MA, Li R, Churchill GA, Carey MC, Paigen B. FXR and ABCG5/ABCG8 as determinants of cholesterol gallstone formation from quantitative trait locus mapping in mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:868–881. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buch S, Schafmayer C, Volzke H, Becker C, Franke A, von Eller-Eberstein H, et al. A genome-wide association scan identifies the hepatic cholesterol transporter ABCG8 as a susceptibility factor for human gallstone disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:995–999. doi: 10.1038/ng2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunhage F, Acalovschi M, Tirziu S, Walier M, Wienker TF, Ciocan A, et al. Increased gallstone risk in humans conferred by common variant of hepatic ATP-binding cassette transporter for cholesterol. Hepatology. 2007;46:793–801. doi: 10.1002/hep.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paigen B, Schork NJ, Svenson KL, Cheah YC, Mu JL, Lammert F, et al. Quantitative trait loci mapping for cholesterol gallstones in AKR/J and C57L/J strains of mice. Physiol Genomics. 2000;4:59–65. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.4.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bouchard G, Johnson D, Carver T, Paigen B, Carey MC. Cholesterol gallstone formation in overweight mice establishes that obesity per se is not linked directly to cholelithiasis risk. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1105–1113. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200102-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerloff T, Stieger B, Hagenbuch B, Madon J, Landmann L, Roth J, et al. The sister of P-glycoprotein represents the canalicular bile salt export pump of mammalian liver. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10046–10050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang R, Salem M, Yousef IM, Tuchweber B, Lam P, Childs SJ, et al. Targeted inactivation of sister of P-glycoprotein gene (spgp) in mice results in nonprogressive but persistent intrahepatic cholestasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031465498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khanuja B, Cheah YC, Hunt M, Nishina PM, Wang DQ-H, Chen HW, et al. Lith1, a major gene affecting cholesterol gallstone formation among inbred strains of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7729–7733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lammert F, Wang DQ-H, Cohen DE, Paigen B, Carey MC. Functional and genetic studies of biliary cholesterol secretion in inbred mice: evidence for a primary role of sister to P-glycoprotein, the canalicular bile salt export pump, in cholesterol gallstone pathogenesis. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 224–228. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green RM, Hoda F, Ward KL. Molecular cloning and characterization of the murine bile salt export pump. Gene. 2000;241:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figge A, Lammert F, Paigen B, Henkel A, Matern S, Korstanje R, et al. Hepatic overexpression of murine Abcb11 increases hepatobiliary lipid secretion and reduces hepatic steatosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2790–2799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang DQ-H, Zhang L, Wang HH. High cholesterol absorption efficiency and rapid biliary secretion of chylomicron remnant cholesterol enhance cholelithogenesis in gallstone-susceptible mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1733:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markel P, Shu P, Ebeling C, Carlson GA, Nagle DL, Smutko JS, et al. Theoretical and empirical issues for marker-assisted breeding of congenic mouse strains. Nat Genet. 1997;17:280–284. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang DQ-H, Paigen B, Carey MC. Phenotypic characterization of Lith genes that determine susceptibility to cholesterol cholelithiasis in inbred mice: physical-chemistry of gallbladder bile. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:1395–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang DQ-H, Lammert F, Paigen B, Carey MC. Phenotypic characterization of Lith genes that determine susceptibility to cholesterol cholelithiasis in inbred mice. Pathophysiology of biliary lipid secretion. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:2066–2079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossi SS, Converse JL, Hofmann AF. High pressure liquid chromatographic analysis of conjugated bile acids in human bile: simultaneous resolution of sulfated and unsulfated lithocholyl amidates and the common conjugated bile acids. J Lipid Res. 1987;28:589–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartlett GR. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey MC. Critical tables for calculating the cholesterol saturation of native bile. J Lipid Res. 1978;19:945–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heuman DM. Quantitative estimation of the hydrophilic-hydrophobic balance of mixed bile salt solutions. J Lipid Res. 1989;30:719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang DQ-H, Carey MC. Measurement of intestinal cholesterol absorption by plasma and fecal dual-isotope ratio, mass balance, and lymph fistula methods in the mouse: an analysis of direct versus indirect methodologies. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1042–1059. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D200041-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang HH, Wang DQ-H. Reduced susceptibility to cholesterol gallstone formation in mice that do not produce apolipoprotein B48 in the intestine. Hepatology. 2005;42:894–904. doi: 10.1002/hep.20867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang HH, Afdhal NH, Gendler SJ, Wang DQ-H. Evidence that gallbladder epithelial mucin enhances cholesterol cholelithogenesis in MUC1 transgenic mice. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:210–222. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lammert F, Wang DQ-H, Paigen B, Carey MC. Phenotypic characterization of Lith genes that determine susceptibility to cholesterol cholelithiasis in inbred mice: integrated activities of hepatic lipid regulatory enzymes. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:2080–2090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang DQ-H, Paigen B, Carey MC. Genetic factors at the enterocyte level account for variations in intestinal cholesterol absorption efficiency among inbred strains of mice. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1820–1830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hillebrandt S, Wasmuth HE, Weiskirchen R, Hellerbrand C, Keppeler H, Werth A, et al. Complement factor 5 is a quantitative trait gene that modifies liver fibrogenesis in mice and humans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:835–843. doi: 10.1038/ng1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geier A, Dietrich CG, Voigt S, Ananthanarayanan M, Lammert F, Schmitz A, et al. Cytokine-dependent regulation of hepatic organic anion transporter gene transactivators in mouse liver. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:G831–841. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00307.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang DQ-H, Carey MC. Complete mapping of crystallization pathways during cholesterol precipitation from model bile: influence of physical-chemical variables of pathophysiologic relevance and identification of a stable liquid crystalline state in cold, dilute and hydrophilic bile salt-containing systems. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:606–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen D, Higman SM, Hsu SI, Horwitz SB. The involvement of a LINE-1 element in a DNA rearrangement upstream of the mdr1a gene in a taxol multidrug-resistant murine cell line. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20248–20254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothbarth K, Hunziker A, Stammer H, Werner D. Promoter of the gene encoding the 16 kDa DNA-binding and apoptosis-inducing C1D protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1518:271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyons MA, Wittenburg H. Cholesterol gallstone susceptibility loci: a mouse map, candidate gene evaluation, and guide to human LITH genes. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1943–1970. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erranz B, Miquel JF, Argraves WS, Barth JL, Pimentel F, Marzolo MP. Megalin and cubilin expression in gallbladder epithelium and regulation by bile acids. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:2185–2198. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400235-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henkel A, Wei Z, Cohen DE, Green RM. Mice overexpressing hepatic Abcb11 rapidly develop cholesterol gallstones. Mamm Genome. 2005;16:903–908. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schafmayer C, Tepel J, Franke A, Buch S, Lieb S, Seeger M, et al. Investigation of the Lith1 candidate genes ABCB11 and LXRA in human gallstone disease. Hepatology. 2006;44:650–657. doi: 10.1002/hep.21289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Acalovschi M, Tirziu S, Chiorean E, Krawczyk M, Grünhage F, Lammert F. Common variants of ABCB4 and ABCB11 and plasma lipid levels: a study in sib pairs with gallstones, and controls. Lipids. 2009;44:521–526. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holt JA, Luo G, Billin AN, Bisi J, McNeill YY, Kozarsky KF, et al. Definition of a novel growth factor-dependent signal cascade for the suppression of bile acid biosynthesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1581–1591. doi: 10.1101/gad.1083503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wooton-Kee CR, Coy DJ, Athippozhy AT, Zhao T, Jones BR, Vore M. Mechanisms for increased expression of cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase (Cyp7a1) in lactating rats. Hepatology. 2010;51:277–285. doi: 10.1002/hep.23289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]