Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the role of angiotensin II (Ang II) in modulating inhibitory and excitatory synaptic inputs to the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray (dl-PAG). The whole cell voltage-clamp recording was performed to examine inhibitory and excitatory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs and EPSCs) of the dl-PAG neurons. Ang II, at the concentration of 2 µM, decreased the frequency of miniature IPSCs from 0.83 ± 0.02 to 0.45 ± 0.03 Hz (P < 0.05) in 10 tested neurons. This did not significantly affect the amplitude and decay time constant. The effect of Ang II on miniature IPSCs was blocked by the prior application of Ang II AT1 receptor antagonist losartan, but not by AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319. Additionally, Ang II decreased the amplitude of evoked IPSCs from 148 ± 15 to 89 ± 7 pA (P < 0.05), and increased the paired-pulse ratio from 96 ± 5% to 125 ± 7% (P < 0.05) in eight tested neurons. In contrast, Ang II had no distinct effects on the EPSCs. Our data suggest that Ang II inhibits GABAergic synaptic inputs to the dl-PAG through activation of presynaptic AT1 receptors.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, Synaptic transmission, GABA, Midbrain PAG

Angiotensin II (Ang II) plays an important role in the control of balance of hydromineral and fluid volume, as well as sympathetic nerve activity [5,26]. Also, Ang II can regulate arterial blood pressure in the development and maintenance of hypertension [6,30]. Ang II receptor subtypes, called AT1 and AT2, are engaged in action of Ang II [12].

The prior studies have revealed the presence of both AT1 and AT2 throughout the rat brain [13,16]. In particular, AT1 receptors are present within the midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) area [16]. Ang II injected into the PAG of rats increases arterial blood pressure [11]. Ang II was likely injected into the lateral or dorsolateral PAG according to the coordinates presented in this previous study. The blockade of AT1 receptors but not AT2 attenuates the increase in blood pressure induced by injection of Ang II [11]. Thus AT1 receptors are likely to play a role in modulating blood pressure in regions of the PAG. However, the underlying mechanisms by which Ang II affects synaptic signaling to the PAG neurons have not specifically been studied. In this study we used an in vitro whole cell recording technique in the midbrain slice to determine the role of Ang II in modulating inhibitory and excitatory synaptic inputs to the PAG.

The PAG receives abundant afferent inputs from the spinal cord [10,15] and also sends descending neuronal projections to the rostral ventrolateral medulla in regulating autonomic activity [33,34]. Among regions of the PAG, activation of the dorsolateral (dl) region contributes to an increase in arterial blood pressure [2]. Thus we postulated that Ang II would decrease GABAergic synaptic inputs and/or increase glutamatergic synaptic inputs to the dl-PAG through activation of presynaptic AT1 receptors.

All procedures outlined in this study were approved by the institutional Animal Care Committee. Sprague–Dawley rats of either gender (4–6 weeks old) were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane oxygen mixture (5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen), and then were decapitated. Briefly, the brain was quickly removed and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) perfusion solution. A tissue block containing the midbrain PAG was cut from the brain and glued onto the stage of the vibratome (Technical Product International, St. Louis, MO). Coronal slices (300 µm) containing the midbrain PAG were dissected from the tissue block in ice-cold aCSF solution. An equilibrium period of 60 min was required to incubate the slices in the aCSF at 34 °C before they were transferred to the recording chamber. During the procedures described above, aCSF were saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2. The aCSF perfusion solution contained (in mM) 124.0 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.3 MgSO4, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.4 NaH2 PO4, 10.0 glucose, and 26.0 NaHCO3 [18,35].

A whole cell voltage-clamp technique was used to record postsynaptic currents in the dl-PAG neurons. Borosilicate glass capillaries (1.2 mm OD, 0.69 mm ID; Harvard Apparatus) were pulled to make the recording pipettes using a puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA). The resistance of the pipette was 4–6 MΩ when it was filled with the internal solution (contained in mM: 130.0 potassium gluconate, 1.0 MgCl2, 10.0 HEPES, 10.0 EGTA, 1.0 CaCl2, and 4.0 ATP-Mg) [18,35]. The solution was adjusted to pH 7.25 with 1 M of KOH and osmolarity of 280–300 mOsm. The slice was placed in a recording chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) and fixed with a grid of parallel nylon threads supported by a U-shaped stainless steel weight. The aCSF saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2 was perfused into the chamber at 3.0 ml/min. The temperature of the perfusion solution was maintained at 34 °C by an in-line solution heater with a temperature controller (Model TC-324; Warner Instruments). Whole cell recordings from the dl-PAG neurons were performed visually using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics on an upright microscope (BX50WI, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The tissue image was captured and enhanced through a camera and displayed on a video monitor. A tight giga-ohm seal was subsequently obtained in the dl-PAG neuron viewed using DIC optics. An equilibration period of 5–10 min was allowed after whole cell access was established and the recording reached a steady state. The recording was abandoned if the monitored input resistance changed was greater than 15%.

The spontaneous miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded in the presence of 1 µM of tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 20 µM of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) at a holding potential of 0 mV. The miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) were recorded in the presence of 1 µM of TTX and 20 µM of bicuculline at a holding potential of −70 mV. QX-314 (10 mM) and GDP-β-s (1 mM) were contained in the pipette solution to block sodium current and possible postsynaptic effects mediated through G proteins in this experiment.

In order to examine the evoked IPSCs (eIPSCs) and evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) in the dl-PAG neurons, electrical stimulation (0.1 ms, 0.4–0.8 mA, and 0.2 Hz) was induced using a bipolar tungsten electrode connected to a stimulator (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA). The tip of the stimulating electrode was placed 200–500 µm away from the recorded neuron. The eIPSCs was determined at a holding potential of 0 mV in the presence of CNQX (20 µM), and eEPSCs was determined at a holding potential of −70 mV in the presence of bicuculline (20 µM), respectively. QX-314 and GDP-β-s were contained in the pipette solution in this experiment.

Single stimuli and paired stimuli at short intervals (50 ms for eIPSCs and 40 ms for eEPSCs) were applied. The paired-pulse ratio (PPR) of eIPSCs and eEPSCs was expressed as percentage (%) of amplitude of the second synaptic response/amplitude of the first synaptic response. Ten consecutive responses were averaged for subsequent analysis. If a compound inhibits transmitter release, this can cause a facilitation of the second pulse to paired stimuli due to an increase in the probability of transmitter release, indicative of a presynaptic locus of action [14,36]. Likewise, if a compound augments transmitter release an attenuation of the second pulse to paired stimuli is seen. Thus, facilitation and attenuation of the PPR are generally used to reflect effects of a certain compound on the presynaptic process [17,18,23].

Ang II, PD123319, TTX, CNQX, bicuculline, QX-314, and GDP-β-S were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Losartan was a gift from Merck and Co., Inc. (Rahway, NY). All drugs were dissolved in the aCSF solution immediately before they were used. According to experimental protocol, the drugs were delivered into the recording chamber at final concentrations using syringe pumps during the experiment [35]. Based on prior studies using the same method [19,20], effective concentrations, such as 2 µM of Ang II; 2 µM of losartan and 5 µM of PD123319, were chosen in this experiment. The responses of IPSCs and EPSCs of the dl-PAG to application of drugs were recorded after control data were collected.

Signals were recorded with a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), digitized at 10 kHz with a DigiData 1440A, and filtered at 1–2 kHz and saved in a PC-based computer using pClamp 10.1 software (Axon Instruments). A liquid junction potential of −15.0 mV (for the potassium gluconate pipette solution) was corrected during off-line analysis [17,18]. The mIPSCs and mEPSCs of the PAG neurons were analyzed off-line with a peak detection program (MiniAnalysis, Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ). Detection of events was accomplished by setting a threshold above the noise level. The distribution of cumulative probability of the inter-event interval and amplitude of mIPSCs and mEPSCs was estimated using the Komogorov–Smirnov test [17,18]. The amplitude of eIPSCs and eEPSCs, and PPR were analyzed using Clampfit 10.1 (Axon Instruments). Experimental data (frequency, amplitude and decay time of mIPSCs and mEPSCs of dl-PAG neurons and the PPR of evoked currents) were analyzed with one-way ANOVA. Tukey’s post hoc analyses were utilized to determine differences between groups, as appropriate. Paired t test was used to analyze data of amplitude of the eIPSCs and eEPSCs. All values were expressed mean ± SE. For all analyses, differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for windows version 15.0.

At the end of each experiment, location of the recording pipette in the PAG slice was visualized and identified under a microscope using the DIC (×40 magnification). This allowed us to determine if neurons tested located in the dl-PAG region. We have confirmed that all cells included for data analysis in this experiment located in the dl-PAG on the basis of the identification with a microscopy and according to Swanson’s rat brain maps [32]. Our prior report has illustrated representative locations of recorded neurons with anterior-posterior coordinates of the sections [23] using the same methods. Whole cell patch-clamp experiments were performed and experimental data were collected from 70 dl-PAG neurons.

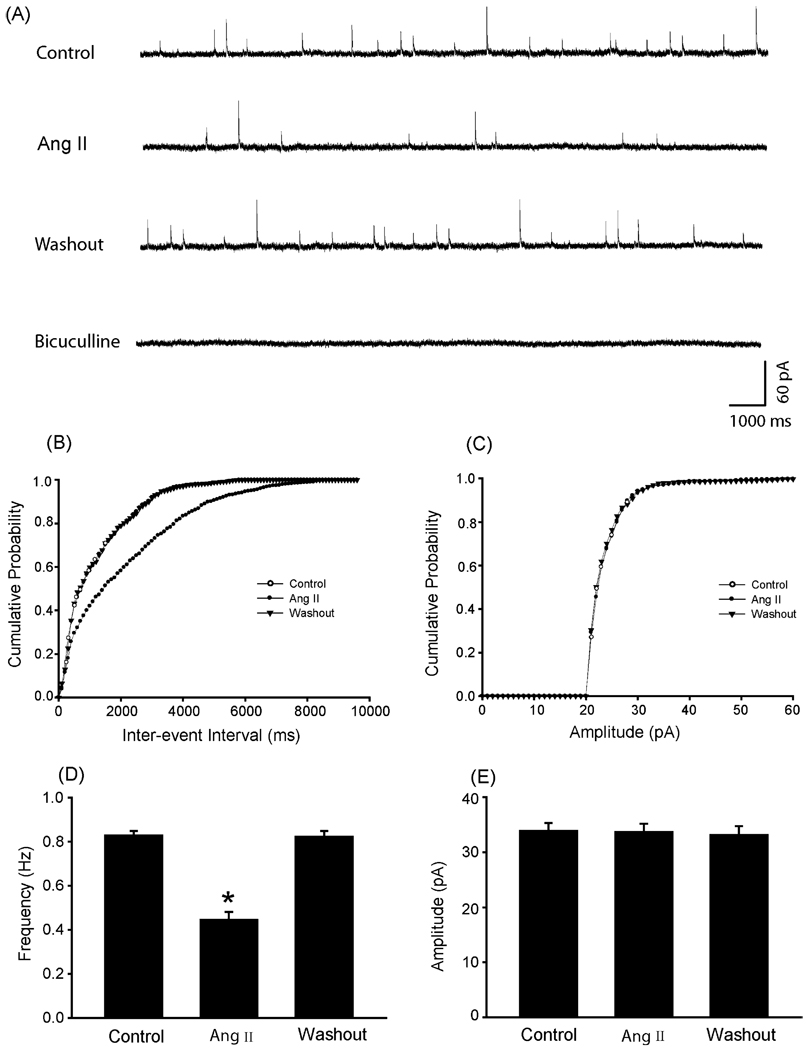

To determine the effects of Ang II on synaptic GABA release onto dl-PAG neurons we recorded the spontaneous mIPSCs obtained from the dl-PAG after application of Ang II (Fig. 1). Ang II, at the concentration of 2 µM, perfused into the recording chamber significantly decreased the frequency of mIPSCs from 0.83 ± 0.02 to 0.45 ± 0.03 Hz (P < 0.05, n = 10), but did not alter the amplitude and the decay time constant of mIPSCs (20.12 ± 0.72 ms in control vs. 20.39 ± 0.83 ms after Ang II, P > 0.05) in all neurons tested. The responses of mIPSCs to Ang II developed at a latency of 7.6 ± 2.2 s. The mIPSCs recovered during washout of the perfusion solution and were completely abolished with bicuculline (Fig. 1A). The cumulative probability analysis of mIPSCs shows that the distribution pattern of the inter-event interval of mIPSCs shifted toward the right but the distribution pattern of the amplitude was not altered as Ang II was applied (Fig. 1B and C). Average data of the Ang II effects on the frequency and amplitude of mIPSC of the dl-PAG neurons are also shown (Fig. 1D and E).

Fig. 1.

Ang II decreased the frequency of GABAergic mIPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons. The effect was observed in 10 neurons tested. (A) Representative tracings from a dl-PAG neuron show that 2 µM of Ang II attenuated the frequency of mIPSCs, and that the mIPSCs recovered during washout and completely abolished in the presence of 20 µM of bicuculline. (B and C) The cumulative probability analysis shows that Ang II increased the inter-event interval of mIPSCs but did not alter the distribution pattern of the amplitude of the mIPSCs. (D and E) Average data show the effects of Ang II on the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons. *P < 0.05, vs. control and washout.

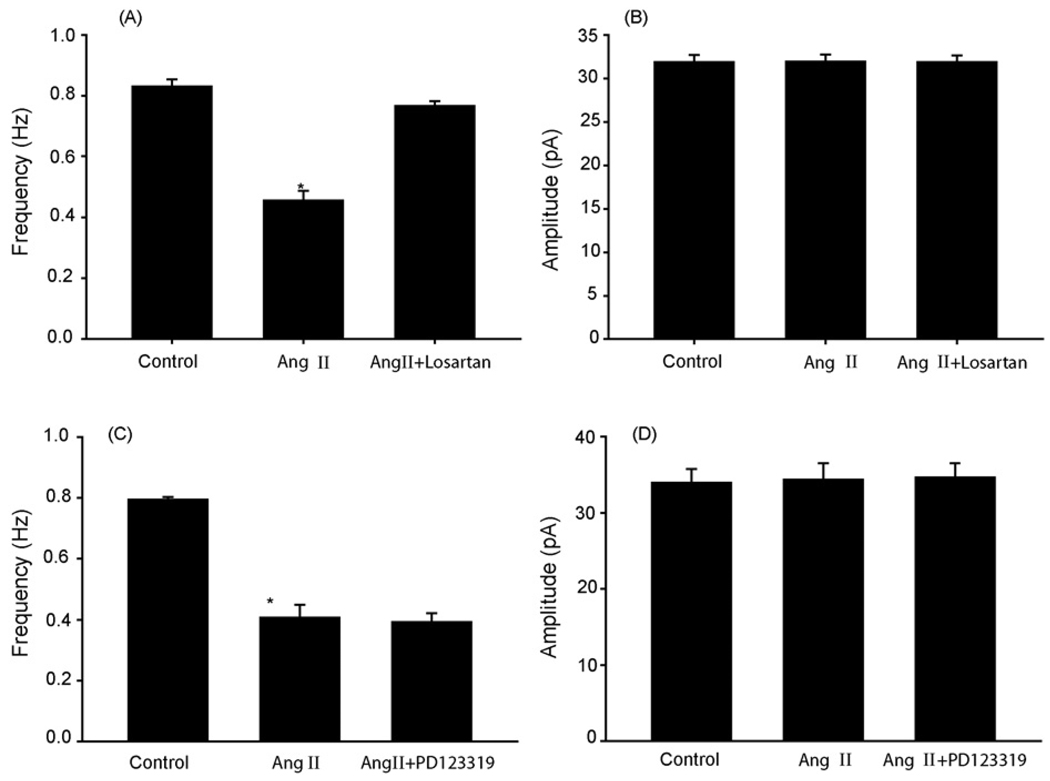

To examine the receptor subtype mediating the inhibitory effect of Ang II on mIPSCs, the specific receptor antagonists to the AT1 (losartan) and AT2 (PD123319) were used. The effective concentrations of these antagonists have been determined previously [20,21]. Ang II (2 µM) failed to decrease the frequency of mIPSCs of eight dl-PAG neurons in the presence of 2 µM of losartan (0.83 ± 0.02 vs. 0.77 ± 0.02 Hz, P > 0.05, Fig. 2A). However, the inhibitory effect of Ang II remained in the presence of 5 µM of PD123319 in eight neurons (Fig. 2C). Fig. 2B and D further show effects of Ang II on the amplitude of mIPSC of the dl-PAG neurons with the prior blockade of AT1 and AT2 receptors.

Fig. 2.

Effects of Ang II on the mIPSCs with the prior application of losartan and PD123319. (A) Summary data showing the antagonizing effect of losartan on Ang II inhibition of the mIPSCs frequency in eight dl-PAG neurons. (B) The mIPSCs amplitude of dl-PAG neurons after Ang II with the prior losartan. (C) Summary data showing that PD123319 had no effect on Ang II attenuation of the mIPSCs frequency in eight dl-PAG neurons. (D) The mIPSCs amplitude of dl-PAG neurons after Ang II with the prior PD123319. *P < 0.05, vs. control and washout.

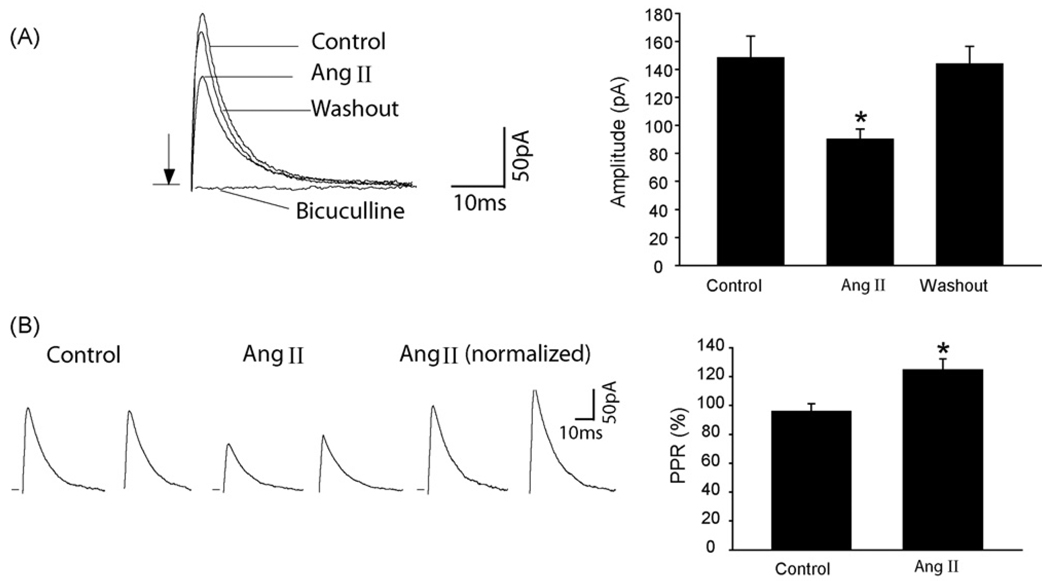

In the next group of experiments, the effect of Ang II on eIPSCs was examined in the dl-PAG neurons (Fig. 3). Ang II significantly inhibited the peak amplitude of eIPSCs in eight tested neurons (Fig. 3A). To further determine whether the effect of Ang II was via presynaptic sites, we examined the PPR of eIPSCs when Ang II was perfused into the recording chamber (Fig. 3B). Ang II significantly augmented the PPR in eight dl-PAG neurons (96 ± 5% in control vs. 125 ± 7% after Ang II, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Ang II attenuated the peak amplitude of eIPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons and increased the PPR of eIPSCs. (A and B) Typical traces from a dl-PAG neuron and average data showing the peak amplitude of eIPSCs during control, Ang II and washout (n = 8); and the PPR of eIPSCs (n = 8). *P < 0.05, vs. control and washout for the amplitude; and vs. control for the PPR. The traces are average of 10 consecutive responses. Stimulation artifacts were removed and indicated by arrows.

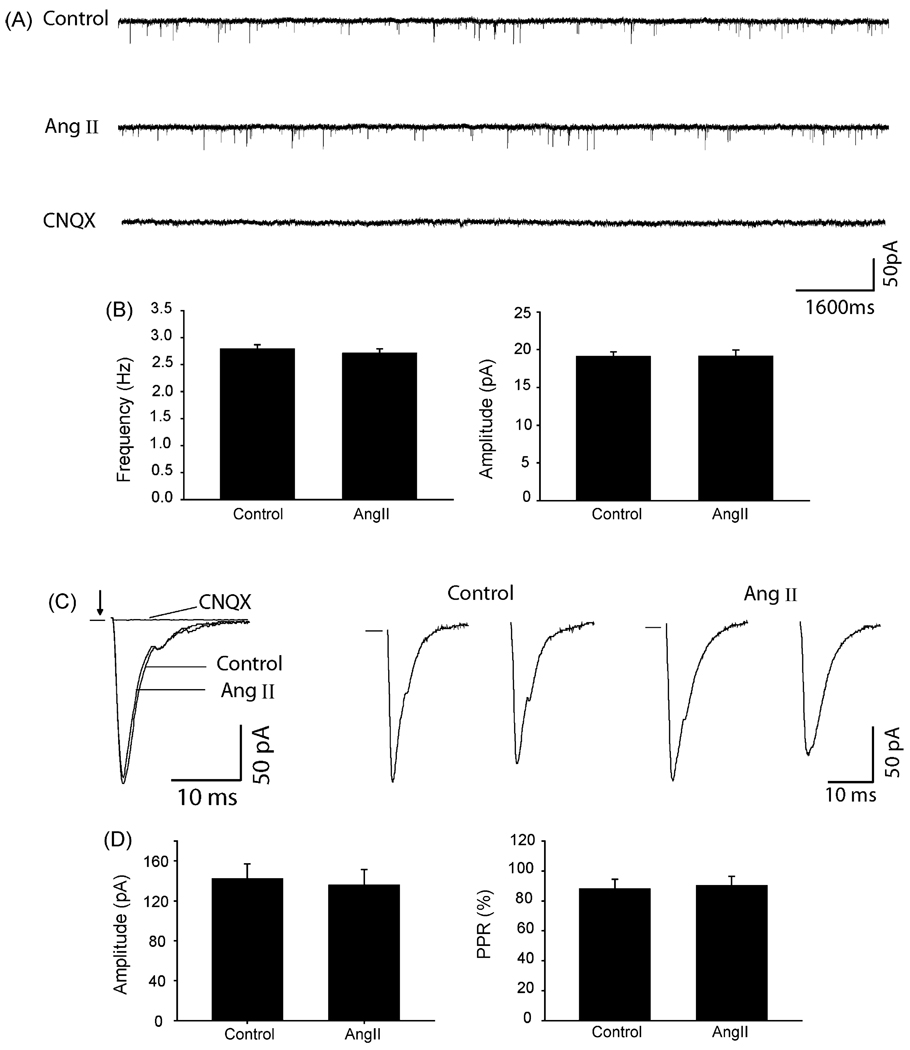

The mEPSCs and eEPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons were also examined to determine the effects of Ang II on synaptic glutamate release onto neurons (Fig. 4). 2 µM of Ang II had no significant effect on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs in seven dl-PAG neurons. The mEPSCs were completely eliminated in the presence of 20 µM of CNQX (Fig. 4A). Average data further show Ang II had no effect on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Ang II had no distinct effects on glutamatergic EPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons. Representative tracings from a dl-PAG neuron (A) and average data (B) show that the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous mEPSCs were not altered by bath application of 2 µM of Ang II. The results were seen in seven neurons tested. Effects of Ang II on eEPSCs were further examined in 19 dl-PAG neurons. Averaged traces of 10 consecutive responses from a dl-PAG neuron (C) and average data (D) show that 2 µM of Ang II did not significantly alter the peak amplitude (n = 10) and PPR (n = 9) of eEPSCs. The mEPSCs and eEPSCs were completely abolished with CNQX.

In another group of experiments, the effect of Ang II on eEPSCs was examined in 19 PAG neurons. Typical traces and average data show that Ang II had no distinct effect on the peak amplitude and PPR of eEPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons (Fig. 4C and D).

In the present study, regulatory effects of Ang II on inhibitory GABAergic and excitatory glutamatergic synaptic activity in the dl-PAG were determined using in vitro PAG slice preparation. Our results have demonstrated that Ang II significantly attenuated the frequency of mIPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons, but had no distinct effect on the amplitude of mIPSCs. These effects were abolished in the presence of AT1 receptor antagonist losartan. Moreover, Ang II significantly decreased the peak amplitude of eIPSCs and increased the PPR. These data suggest that stimulation of AT1 inhibits the synaptic GABA release in the PAG and the site of the action is likely at the presynaptic GABAergic terminals.

GABA-mediated neuronal elements constituting ~50% of the total population of neurons play a crucial role in the intrinsic neuronal circuitry of the PAG [24,28]. The GABA synaptic inputs make up ~50% of the synaptic innervation of the PAG neurons and the majority of GABAergic neurons are tonic active interneurons [31]. The release of GABA from those neurons may play a role in modulation of the synaptic inputs to the PAG neurons. Studies have further shown that GABAA receptors are dense within the PAG [4,8].

The effects of Ang II on the inhibitory GABAergic inputs to the PAG neurons were examined in this experiment. The mIPSCs represent the synaptic quanta release of GABA that plays a role in modulating the activity of the postsynaptic neuron. On the basis of the data showing that Ang II had an inhibitory effect on the IPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons, we have further determined the receptor subtype that mediated the inhibition of Ang II on the IPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons in this study. Our results suggest that Ang II suppresses GABAergic synaptic inputs to the dl-PAG through stimulation of the presynaptic AT1 receptors. Also, the presynaptic disinhibition of Ang II is likely to increase activity of the dl-PAG neurons. A prior study has reported that Ang II attenuates GABAergic synaptic inputs to paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus through activation of presynaptic AT1 receptors thereby exciting the neuronal activity [20].

In addition, glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter, appears in the dl-PAG region [3]. The PAG also has the high density of excitatory amino acid binding sites (glutamate receptor subtypes) including a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA)/kainate, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and metabotropic receptors [1,9]. Thus the effects of Ang II on the excitatory glutamatergic inputs to the dl-PAG neurons were also examined in this experiment. In contrast, Ang II had no distinct effects on the frequency and amplitude of glutamatergic mEPSCs, and amplitude of eEPSC recorded from the dl-PAG neurons. This suggests the lack of Ang II effects on the synaptic glutamatergic terminals in the dl-PAG. However, it is interesting to note that Ang II can potentiate glutamatergic synaptic inputs in the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus [25].

AT1 receptors have been shown to appear within the midbrain PAG area [16]. A previous study has further shown that stimulation of AT1 but not AT2 receptors in the PAG induces an increase in blood pressure [11]. This result suggests that the central actions of Ang II in the regulation of blood pressure are predominantly mediated by AT1 receptors. Data from our current experiments provide electro-physiological evidence that Ang II receptor AT1 is likely to appear on presynaptic nerve terminals in the dl-PAG and that activation of AT1 receptors decreases GABA release from presynaptic sites. It is anticipated that a decrease in inhibitory activities to the dl-PAG neurons is likely engaged in the blood pressure regulation of Ang II.

Besides the autonomic regulation, Ang II has been reported to play a role in modulating autonomic, nociceptive and behavioral (i.e. thirst) responses in the PAG [27,29]. The effects of Ang II may be through presynaptic AT1 inhibition of GABAergic inputs on the basis of the data provided in our present experiment. Although Ang II acts as a neurotransmitter or modulator in several regions of the brain including the PAG [11,27,29], the specific sources of Ang II in the PAG are not completely clear. We postulate that a major source of the angiotensinergic inputs to the PAG is circumventricular organs like the source of Ang II to other brain regions [22]. There is likely a neuronal connection between the subfornical organ and regions of the PAG because the pressor response induced by microinjection of Ang II into the subfornical organ is attenuated by Ang II antagonists injected bilaterally into the PAG [7].

In summary, Ang II significantly decreases the frequency of GABAergic mIPSCs as well as the amplitude of eIPSCs but not glutamatergic EPSCs of the dl-PAG neurons. The effect is mediated via stimulation of the presynaptic AT1 receptors. Our results provide new information for understanding the role played by Ang II in modulating activities of the dl-PAG neurons.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH R01 HL075533 and R01 HL078866.

References

- 1.Albin RL, Makowiec RL, Hollingsworth Z, Dure LS, Penney JB, Young AB. Excitatory amino acid receptors in the periaqueductal gray of the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1990;118:112–115. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandler R, Carrive P, Zhang SP. Integration of somatic and autonomic reactions within the midbrain periaqueductal gray: viscerotopic, somatotopic and functional organization. Prog. Brain Res. 1991;87:269–305. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beitz AJ, Williams FG. In: Localization of putative amino acid transmitters in the PAG and their relationship to the PAG–raphe magnus pathway. Depaulis A, Bandler R, editors. Plenum, NewYork: The Midbrain Periaqueductal Gray Matter; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowery NG, Hudson AL, Price GW. GABAA and GABAB receptor site distribution in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1987;20:365–383. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks VL. Interactions between angiotensin II and the sympathetic nervous system in the long-term control of arterial pressure. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1997;24:83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruner CA, Kuslikis BI, Fink GD. Effect of inhibition of central angiotensin pressor mechanisms on blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1987;9:298–304. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang YZ, Gu YH. Role of brain angiotensin II system in subfornical organ-pressor responses. Acta Physiol. Sinica. 1999;51:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu CDM, Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. Distribution and kinetics of GABAB binding sites in rat central nervous system: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 1990;34:341–357. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90144-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotman CW, Monaghan DT, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Anatomical organization of excitatory amino acid receptors and their pathways. Trends Neurosci. 1987;10:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig AD. Distribution of brainstem projections from spinal lamina I neurons in the cat and the monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;361:225–248. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Amico M, Di Filippo C, Berrino L, Rossi F. AT1 receptors mediate pressor responses induced by angiotensin II in the periaqueductal gray area of rats. Life Sci. 1997;61:PL17–PL20. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ian Phillips M, Shen L, Richards EM, Raizada MK. Immunohistochemical mapping of angiotensin AT1 receptors in the brain. Regul. Pept. 1993;44:95–107. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(93)90233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Counting quanta: direct measurements of transmitter release at a central synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keay KA, Feil K, Gordon BD, Herbert H, Bandler R. Spinal afferents to functionally distinct periaqueductal gray columns in the rat – an anterograde and retrograde tracing study. J. Compd. Neurol. 1997;385:207–229. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970825)385:2<207::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenkei Z, Palkovits M, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortès C. Expression of angiotensin type-1 (AT1) and type-2 (AT2) receptor mRNAs in the adult rat brain: a functional neuroanatomical review. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 1997;18:383–439. doi: 10.1006/frne.1997.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li D-P, Chen S-R, Pan H-L. Nitric oxide inhibits spinally projecting paraventricular neurons through potentiation of presynaptic GABA release. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2664–2674. doi: 10.1152/jn.00540.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D-P, Chen S-R, Pan H-L. VR1 receptor activation induces glutamate release and postsynaptic firing in the paraventricular nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1807–1816. doi: 10.1152/jn.00171.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li D-P, Pan H-L. Angiotensin II attenuates synaptic GABA release and excites paraventricular-rostral ventrolateral medulla output neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;313:1035–1045. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li DP, Chen SR, Pan HL. Angiotensin II stimulates spinally projecting paraventricular neurons through presynaptic disinhibition. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5041–5049. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05041.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Ferguson AV. Angiotensin II responsiveness of rat paraventricular and subfornical organ neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 1993;55:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90466-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Ferguson AV. Subfornical organ efferents to paraventricular nucleus utilize angiotensin as a neurotransmitter. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:R302–R309. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.2.R302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J, Xing J, Li J. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) inhibits glutamatergic synaptic transmission in dorsolateral periaqueductal gray (dl-PAG) Brain Res. 2007;1162:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mugnaini E, Oertel WH. An atlas of the distribution of GABAergic neurons and terminals in the rat CNS as revealed by GAD immunohistochemistry. In: Bjorklund A, Hokfelt T, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy 4: GABA and Neuropeptides in the CNS. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozaki Y, Soya A, Nakamura J, Matsumoto T, Ueta Y. Potentiation by angiotensin II of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents in rat supraoptic magnocellular neurones. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:871–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peach MJ. Renin-angiotensin system: biochemistry and mechanisms of action. Physiol. Rev. 1977;57:313–370. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1977.57.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prado WA, Pelegrini-da-Silva A, Martins AR. Microinjection of rennin-angiotensin system peptides in discrete sites within the rat periaqueductal gray matter elicits antinociception. Brain Res. 2003;972:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02541-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichling DB. GABAergic neuronal circuitry in the periaqueductal gray matter. In: Depaulis A, Bandler R, editors. The Midbrain Periaqueductal Gray Matter. New York: Plenum; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sewards TV, Sewards MA. The awareness of thirst: proposed neural correlates. Conscious. Cogn. 2000;9:463–487. doi: 10.1006/ccog.2000.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steckelings UM, Obermuller N, Bottari SP, Qadri F, Veltmar A, Unger T. Brain angiotensin: receptors, actions and possible role in hypertension. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1992;70:S23–S27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1992.tb01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strack AM, Sawyer WB, Hughes JH, Platt KB, Loewy AD. A general pattern of CNS innervation in the sympathetic outflow demonstrated by transneuronal pseudorabbits viral infection. Brain Res. 1989;491:156–162. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swanson LW. Brain Maps: Structure of the Rat Brain. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tjen-A-Looi SC, Li P, Longhurst JC. Midbrain vlPAG inhibits rVLM cardiovascular sympathoexcitatory responses during electroacupuncture. Am. J. Physiol. 2006;290:H2543–H2553. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01329.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verberne AJM, Guyenet PG. Midbrain central gray: influence on medullary sympathoexcitatory neurons and the baroreflex in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:R24–R33. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.1.R24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing J, Li J. TRPV1 receptor mediates glutamatergic synaptic input to dorsolateral periaqueductal gray (dl-PAG) neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;97:503–511. doi: 10.1152/jn.01023.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]