Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains one of the most pernicious of human pathogens. Current vaccines are ineffective and drugs, although efficacious, require prolonged treatment with constant medical oversight. Overcoming these problems requires a greater appreciation of M. tuberculosis in the context of its host. Upon infection of either macrophages in culture or animal models, the bacterium re-aligns its metabolism in response to the new environments it encounters. Understanding these environments, and the stresses that they place on M. tuberculosis, should provide insights invaluable for the development of new chemo- and immuno-therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) remains an enduring pathogen of mankind. Despite numerous “eradication” programs over the past century its penetrance remains at approximately 1/3 of the human population of which between 5–15% will develop active disease during the course of their lifetime. The success of this pathogen lies in its ability to maintain the infection throughout the life of the human host, ready to reactivate without apparent cause in immunocompetent individuals, or in response to immune suppression in HIV patients or other immunocompromised individuals. The ability of Mtb to infect many of the individuals in a population yet only cause active disease in a few likely aided the persistence of the pathogen throughout human evolution, where, until recently, mankind existed as isolated groups of individuals. Infectious agents with more acute disease profiles run the risk of eradicating their host population, unless they have animal reservoirs, which Mtb lacks.

As a persistent pathogen, Mtb exhibits many characteristics shared by other infectious agents capable of sustained infections. Firstly, the stable or chronic infection state of such pathogens is usually maintained by a relatively low, and relatively constant, parasite load. Secondly, because of the enduring nature of this infection these pathogens must either avoid the induction of an acquired immune response, or subvert its consequences at the localized level of the infection.

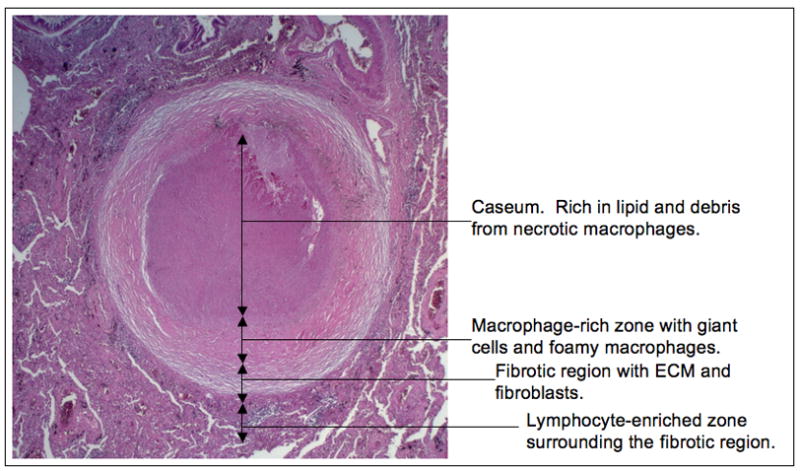

Early in infection tuberculosis follows a relatively reproducible course. It is inferred that the first infected cell is the alveolar macrophage that internalizes the bacilli following inhalation of droplets aerosolized by individuals with active TB (Leemans et al., 2001; Wolf et al., 2007). The infected macrophage invades the subtending epithelium and the resultant proinflammatory response leads to recruitment of monocytes from the bloodstream. This early, innate granulomatous response is sustained primarily by phagocytes such as macrophages, monocytes and neutrophils (Tsai et al., 2006; Wolf et al., 2007). Analysis of murine lungs during this early phase of infection has demonstrated that the bacteria are retained almost exclusively within phagocytes. Once an acquired immune response develops the granuloma becomes a stratified lesion with macrophages, giant cells and foamy macrophages in the center, surrounded by the lymphocyte-rich marginal zone (Flynn and Chan, 2005; Russell, 2007; Russell et al., 2009a; Ulrichs and Kaufmann, 2006). In many lesions these cell populations are separated by a fibrous layer of extracellular matrix, see figure 1. In an infected individual, even one with active disease, granulomas exist in all states of development from sterility, to containment, to cavitation and release of infectious bacilli. This implies that, in immunocompetent individuals at least, the “decisions” that culminate in progression to active disease are determined locally, at the level of each individual granuloma.

Figure 1. The main features of the human TB granuloma.

A fully-formed human TB granuloma is an extremely stratified structure. The center of the granuloma is caseous in nature and rich in lipids, thought to be derived from the lipids present in foamy macrophages. The caseum is surrounded by a macrophage-rich layer that contains foamy macrophages, multi-nucleate giant cells and epithelioid macrophages. Mtb bacilli are observed in many of these cells. This structure is frequently encased in a fibrous capsule of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins. Lymphocytes tend to be restricted to the periphery of the granuloma outside the fibrous outer layer.

Several decades of histological observations from in vivo infections in humans and animal models have documented that the macrophage is the predominant host cell for much of the infection cycle prior to the release of bacteria into the cavitating lesion. Therefore, understanding the basis of survival of Mtb within this phagocyte remains one of the key questions in appreciating why this pathogen has been so successful. The macrophage is known to be the primary defense mechanism against microbial invasion (Deretic et al., 2009; Liu and Modlin, 2008; Nathan and Shiloh, 2000). It has a phagocytic system that delivers the microbe into a compartment that is the site of generation of reactive oxygen intermediate, increasing acidity, hydrolytic activity, and the presence of anti-microbial peptides. All of these killing pathways are impacted by the immune status of the host macrophage, and activation with cytokines such as interferon-γ leads to control of the intracellular infection (Cooper et al., 1993; North and Jung, 2004). It is within the context of this environment that anti-Mtb drugs or vaccines need to function, therefore appreciating the pressure points of macrophage-mediated stress, and the Mtb responses, are critical to both understanding the biochemical basis of Mtb’s survival and the development of novel intervention strategies.

Biology of the phagosome

The macrophage forms a phagosome around any particle that has ligated receptors capable of triggering internalization. Studies on phagosomes containing inert particles such as IgG-opsonized beads have developed a comprehensive understanding of the physiological changes active within the lumen of the phagocytic compartment (Russell et al., 2009b; VanderVen et al., 2009; Yates et al., 2005; Yates et al., 2007; Yates and Russell, 2005). The phagosome acidifies to below pH 5.0 within 10–12 minutes, and reaches equilibrium with lysosomal content within 90 minutes post-internalization. This transition is marked by increasing hydrolytic activities such as proteolysis, lipolysis and nucleotidase activity. In addition, ligation of certain phagocytic receptors, such as the Fc receptor will trigger generation of superoxide in both resting and activated macrophages. The superoxide burst is transient, enduring for 10–15 minutes post-receptor ligation, and is enhanced in intensity, but not duration, through activation by TLR agonists or IFN-γ (VanderVen et al., 2009). The phagosome possesses an impressive armamentarium that has to be avoided, negotiated, or suppressed by any aspiring intra-macrophage pathogen.

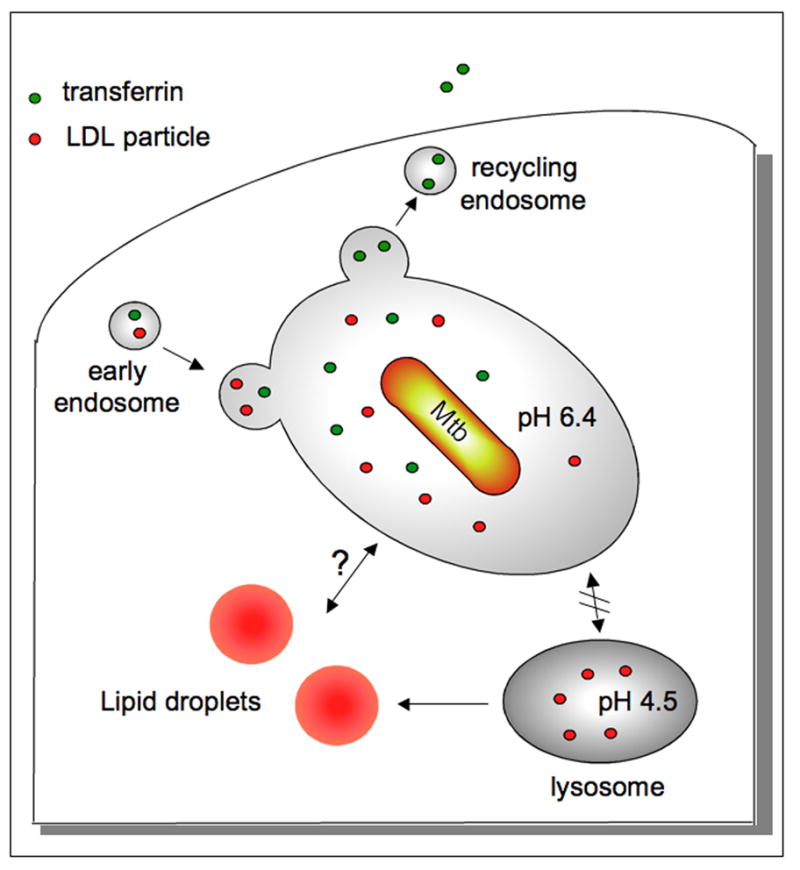

Mtb’s primary mode of operation is one of avoidance. Once inside the phagocytic compartment, the normal progression of the phagosome is arrested prior to the acquisition of bactericidal characteristics, see figure 2. The pH of the Mtb-containing phagosome is pH 6.4 (Sturgill-Koszycki et al., 1994). Certainly this is more acidic than the extracellular milieu, but it is considerably higher than that of a terminal lysosome, pH 4.5–5.0 (Yates et al., 2005). Numerous bacterial moieties have been implicated in this process from cell wall glycolipids (Axelrod et al., 2008; Katti et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2007; Vergne et al., 2003), to secreted proteins (Vergne et al., 2005; Walburger et al., 2004), of which the latter have been proposed to access the host cell cytosol.

Figure 2. Diagram of the Mtb-containing phagosome.

Mtb resides in a phagosome that is arrested at the early endosomal stage of maturation and fails to fuse with mature lysosomes. The pH of the vacuole is pH 6.4 and the compartment remains fusigenic and continues to mix with the recycling endosomal system (Clemens and Horwitz, 1996; Sturgill-Koszycki et al., 1996; Sturgill-Koszycki et al., 1994). Endosomal cargo, such as transferrin, can be visualized passing through the Mtb-containing vacuole.

The trafficking of LDL bound to the LDL receptor mirrors that of transferrin. LDL is likely processed by the lipoprotein lipase in the early endosome (Heeren et al., 2001), which could render the cholesterol core accessible to the bacterium. In the host cell, cholesterol is transported into the cytosol and complexed with cholesterol-binding proteins prior to its esterification and incorporation into lipid droplets within the leaflets of the ER membrane. At later stages in foamy macrophages, Mtb has been observed within the lipid droplets in the cells indicating that there can be direct communication between the Mtb-containing vacuole and the droplets (Peyron et al., 2008). This association is consistent with genetic evidence indicating that Mtb exploits cholesterol as a carbon source during infection (Pandey and Sassetti, 2008).

Comparisons between the Mtb phagosome and inert particle-containing phagosomes allow one to make certain predictions about the physiological status of the phagosome lumen (Russell et al., 2005). In an IgG-bead phagosome at pH 6.4 there is minimal measurable proteolytic activity, and minimal mixing with lysosomal cargo suggesting acquisition of lysosomal antimicrobial peptides will be low. Intriguingly, there is one activity that is high in early phagosomes, that is lipolysis, which presumably is required for the processing of LDL particles that cycle through the early endosomal compartment (Heeren et al., 2001; Sugii et al., 2003). This lipolytic activity is mediated by Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL) and other hepatic lipase family members. Given the shift to lipid catabolism exhibited by intracellular Mtb, this activity might have special significance for the physiology of this compartment. Recent whole cell-based screens for lipase inhibitors have identified novel inhibitors of these activities, and acid lipase activity, which may provide fresh insights into the importance of this host cell-derived activity to bacterial survival (VanderVen et al., 2010).

Activation of the host macrophage by either TLR agonists or IFN-γ leads to alterations in the Mtb-containing phagosome that impact negatively on the bacterium’s capacity to replicate and/or survive (MacMicking et al., 2003; Schaible et al., 1998; Via et al., 1998). The primary killing mechanism in activated macrophages is through the production of reactive nitrogen intermediates generated by the activity of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (MacMicking et al., 1997). NO-mediated killing, however, functions in tandem with other activities such as the increased acidification of the phagosome (to pH 5.2), which halts bacterial replication, and exposure to lysosomal hydrolases and anti-bacterial peptides in the macrophage lysosome (Alonso et al., 2007; Gutierrez et al., 2004). These activation states are not binary and host phagocytes are likely to exist across a broad spectrum of activation states that are linked to their location within granulomas. The heterogeneity in both pathogen and host renders interpretation of data from population-based studies such as transcriptome analysis or genome-wide genetic screens difficult to interpret without extensive underpinning from in vitro infection models.

In addition to intra-phagosomal survival, investigators also report that Mtb, along with other mycobacterial spp., are capable of escaping the phagosome and accessing the cytoplasm (van der Wel et al., 2007). While the data that this occurs in some intracellular infection models are compelling (Hagedorn et al., 2009; van der Wel et al., 2007) the majority of studies on intracellular survival of Mtb in murine macrophages do not observe cytosolic bacteria. It is likely therefore that escape from the vacuole is not a requirement for bacteria survival and growth. However, the possibility that Mtb has an albeit transient cytosolic location during infection has major implications for nutrient utilization, and the possible significance of a cytosolic phase in vivo needs to be examined in greater depth.

Mtb’s response to the intracellular environment

Despite the fact that Mtb arrests maturation of its phagosome prior to fusion with lysosomes the intracellular environment is likely to be extremely different from that encountered by the bacterium in rich culture medium. This environmental transition has been probed by several groups exploiting genome-wide microarray analysis of the bacterial transcriptome. The original study by Schnappinger and colleagues detailed transcriptional responses consistent with the intracellular environment being limited in nutrients and exerting considerable oxidative and nitrosative stress, particularly in activated macrophages (Schnappinger et al., 2003). In addition, they noted up-regulation of genes in the DosR regulon, which can respond to a range of stresses such as nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, low pH and SDS (Rustad et al., 2009). The study also reported the up-regulated expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism, consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that perturbation of carbon flow from lipid metabolism reduces the virulence of intracellular Mtb (McKinney et al., 2000).

A more recent study focusing on the initial response of Mtb to transition into the phagosome identified a smaller set of genes (68 genes) whose expression was up-regulated 2 hr post-infection in murine macrophages (Rohde et al., 2007). When the ability of the macrophage to acidify its phagosome was blocked pharmacologically with the proton ATPase inhibitor Concanamycin A (Cca), a subset of 24 genes was no longer up-regulated. This indicates that, although the Mtb-containing phagosome does not fuse with lysosomes, the pH drop from pH 7.0 in the external medium, to pH 6.4 in the Mtb vacuole constitutes a dominant environmental signal that shapes the transcriptional response of the bacterium. Mtb expresses a PhoP homolog (Buchmeier et al., 2000) and PhoP has been demonstrated to be the major pH sensor in intracellular bacteria such as Salmonella (Martin-Orozco et al., 2006). Interestingly, many of the 24 Cca-sensitive, pH-regulated genes have also been shown to be regulated by PhoP (Walters et al., 2006). Mtb mutants defective in PhoP demonstrate a marked drop in virulence in the murine model. Although this phenotype may be driven by the loss of virulence-associated methyl branched lipids or the absence of ESAT6/CFP10 secretion in the PhoP mutant, it is also consistent with pH-sensing playing an important role in adapting to an intracellular existence (Frigui et al., 2008; Ludwiczak et al., 2002; Perez et al., 2001).

Several groups have now performed array analysis of the Mtb transcriptome in infection models and, while broad themes are conserved and reproduced faithfully, there is considerable variation between the datasets. These variations are likely due to bacterial strains, and culture and experimental conditions; however they do limit the reliability of the datasets for identification of candidate genes key to survival. To address this issue, and to establish a “core” intracellular transcriptome, we examined the transcriptional profile of 15 recent clinical isolates that provide representation across the genetically-distinct strains of the Mtb Complex that span the globe, which includes M. tuberculosis and the closely related African species such as M. africanum (Homolka et al., 2010). Analysis of the transcriptional profiles of these clinical isolates both in broth culture and 24 hours post-infection in murine macrophages demonstrated the following points. First, condition-tree analysis of the transcriptional profiles segregated according to genotype indicating that the genetic variation translated into functional diversity across these strain. This is consistent with the emerging realization that the Mtb Complex is more heterogeneous than appreciated previously. Second, from all of these strains we were able to define a universal, or “core” transcriptome induced by the intracellular environment, figure 3. This transcriptome consists of 280 genes with 168 genes induced and 112 genes repressed in all isolates examined. The transcriptome reflects exposure to host-mediated stress with increased expression of genes connected with hypoxia, radical stress, cell wall remodeling, and lipid metabolism. This response was emphasized further in Mtb from activated macrophages, which also exhibited a strong down-regulation of expression of genes linked to bacterial growth, such as ribosomal subunits. The ubiquitous expression and conserved regulation of these genes across this diverse panel of clinical strains forms a powerful argument for prioritization of drug targets or vaccine candidates. Finally, while all these intramacrophage studies have been extremely informative, the infection of the macrophage in culture does not reflect all of the environments that the bacterium will encounter in the tissues of its human host.

Figure 3. Venn diagram of the universally-expressed transcriptome.

The Venn diagrams illustrate those genes with conserved expression and regulation inside macrophage across the panel of MTC clinical isolates. The gene expression profiles of 17 MTC strains 24h post-infection of resting macrophages and macrophages activated overnight with interferon-γ were determined by microarray. Normalized expression ratios for each strain were determined by comparison of RNA from intracellular bacteria versus control bacteria of the same strain in medium (Homolka et al., 2010). This enabled the delineation of the macrophage-specific response for each individual isolate. The Venn diagrams illustrate the activation-dependent (magenta) and independent (green) genes, together with those genes up or down-regulated independent of macrophage status across clinical isolates (merged). Genes in the core transcriptome were selected based on trending up or down in all strains (up or down >1.2-fold in 15 of 17 strains).

Latency, dormancy and the state of non-replication

Once the infection has established itself in its host, the growth pattern across the bacterial population appears relatively conserved in animal models. There is a period of rapid replication until the host develops an acquired immune response and at that time the granuloma adopts a more stratified structure with a lymphocytic cuff. At this stage in the infection the bacterial population stabilizes and remains constant within the lung (North and Jung, 2004). At this point there are no overt signs of disease and the infection is under immune-mediated control. When analyzed at the gross level, the constant bacterial load implies reduced growth, however, attempts to determine whether or not this represents a static population or overlapping curves of replication and death have produced mixed results. Earlier experiments attempting to detect accumulation of cell wall debris by electron microscopy (Rees and Hart, 1961), or the rigorous quantitation of genome equivalents (Munoz-Elias et al., 2005) indicated that the bulk of the bacterial population was non-replicating. However, more recent use of an unstable “clock” plasmid, which is lost at a predictable rate during bacterial division, has generated some intriguing new insights into the bacteria population in vivo (Gill et al., 2009). Data from this latter study indicate that colony-forming unit counts underestimate the bacterial population by approximately one log and that the bacteria continue to replicate throughout the duration of the experimental infection (111 days). The authors argue that the population remains dynamic and that altered rates of killing rather than replication are the primary factor that determines the overall bacterial burden. However, all three studies were performed in mice, which do not generate the structured granulomas observed in human infection, therefore, while this is an important observation we still need to determine the metabolic state of Mtb required to sustain a chronic infection in the real host, humans.

Hypoxia has long been considered as the dominant environmental condition that regulates bacterial growth during the chronic phase of infection (Deb et al., 2009; Wayne and Sohaskey, 2001). Models involving controlled reduction of oxygen in in vitro culture conditions establish a non-replicative state from which Mtb recovers vigorously. The use of the hypoxia indicator Pimonidazole in humans, coupled to the direct measurements of oxygen tension in granulomas from primates and rabbits, have confirmed the belief that advanced granulomas, with the loss of vasculature, represent a microaerophilic environment (Via et al., 2008). When Mtb is exposed to a low O2 environment it up-regulates genes that are controlled, at least initially, by the dosS, dosT and dosR encoded regulator complex (Boon and Dick, 2002; Park et al., 2003). The DosR regulon comprises approximately 48 early response genes that support survival of the bacilli in an anaerobically-induced state of “dormancy”, shift the bacteria’s metabolism from aerobic to anaerobic, and support exit of Mtb from dormant the state into one of active replication (Leistikow et al., 2009; Rustad et al., 2009). However, in infection studies performed on mice, guinea pigs and rabbits, mutants of Mtb that were defective in dosR revealed only a minimal phenotype (Converse et al., 2009). This calls into question either the hypoxic state in the in vivo infection, or the suitability of these animal models for reproducing the low oxygen environment found in the TB granulomas of higher primates.

Re-alignment of Mtb metabolism inside the host

The shift in metabolism exhibited by Mtb in the host has been revealed by the loss of virulence of bacteria defective in different genes important for lipid metabolism (Brzostek et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2009; McKinney et al., 2000; Movahedzadeh et al., 2004; Nesbitt et al.), and by alterations in the cell wall lipids that the bacterium expresses in liquid culture versus in infection models (Gonzalo Asensio et al., 2006; Reed et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2009; Walters et al., 2006). This is likely preserved in in vivo infections where it has been reported that Mtb lose their acid-fastness and become difficult to detect (Ulrichs and Kaufmann, 2006). The full significance of these alterations in lipid metabolism has yet to be revealed, however, there are several observations that are coming together to identify the issues facing Mtb when exploiting lipids as an accessible carbon source within the host.

In an early observation, isocitrate lyase (icl1) was shown to be required for survival in macrophages and mice where the host exhibited an intact immune response and was capable of activating the host cell (McKinney et al., 2000). ICL is the gating enzyme into the glyoxylate cycle, which shunts carbon from the Kreb’s Cycle through to pyruvate and possibly, into gluconeogenesis. The glyoxylate cycle is required to retain carbon when growing on fatty acids as the limiting carbon source. Recently, however, a significant role for ICL1 and ICL2 during in vitro culture and in vivo infection was shown to be the completion of the 2-methyl citric acid cycle (Munoz-Elias et al., 2006), figure 4. The metabolism of cholesterol, methyl-branched fatty acids and amino acids, and odd-chain-length fatty acids all lead to the generation of the C3 product propionyl-CoA, which is toxic to Mtb unless metabolized (Savvi et al., 2008). The 2-methyl citric acid cycle condenses propionyl-CoA with oxaloacetate to produce pyruvate and the Kreb’s cycle intermediate, succinate. In the context of 2-methyl citric acid cycle, ICL1 and ICL2 operate as 2-methylisocitrate lyases (Munoz-Elias et al., 2006). Therefore an important function of ICL1/2 appears to be relieving the toxicity caused by propionyl-CoA build up.

Figure 4. Outline of the pathways relevant to C3 metabolism.

The metabolism of cholesterol, methyl-branched fatty acids and odd-chain length lipids will raise the intracellular levels of the C3 compounds propionate or propionyl-CoA, which Mtb finds highly toxic. The bacterium has developed three different strategies to detoxify propionyl-CoA. Isocitrate lyase activity has been suborned to fulfill the function of methylcitrate lyase in the last step of the methyl citrate cycle to generate the TCA cycle intermediate succinate. The methylmalonyl pathway has also been mobilized to metabolize propionyl-CoA to produce succinyl-CoA via the VitB12-dependent activity of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. Finally, intermediates from the methylmalonyl pathway can be incorporated directly into the abundant, methyl-branched lipids of the bacterial cell wall, such as PDIM and SL-1.

The detoxification of propionyl-CoA pools seems absolutely critical to Mtb and the bacterium has also evolved to utilize methylmalonyl-CoA intermediates to fulfill a similar function, figure 4. In Mtb, propionyl-CoA can be converted to methylmalonyl-CoA. The final step of the methylmalonyl pathway is the conversion of methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, which is performed by the VitB12-dependent enzyme methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MutAB) (Savvi et al., 2008). The methylmalonyl pathway enables Mtb to grow on propionate in the presence of inhibitors of ICL activity, but requires supplementation of the medium with VitB12 because methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, the final enzyme of the methylmalonyl pathway, is a VitB12-dependent enzyme. Additionally, methyl-branched fatty acids can be synthesized directly from methylmalonyl-CoA precursors thus, propionyl-CoA products can be incorporated into cell wall lipids and detoxified. Mtb produces many complex lipids containing methyl-branched fatty acid side chains that are integral to the Mtb cell wall (Jackson et al., 2007). Recently, it was shown that Mtb grown on propionate as the limiting carbon source exhibit enhanced synthesis of the virulence-associated methyl-branched lipids sulfolipid (SL-1) and phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIM) (Jain et al., 2007). In addition, when Mtb was grown on propionate or odd chain fatty acids the mycocerosic acids in PDIM were extended by 3-carbons implying direct incorporation of the methylmalonyl-CoA intermediate. Lastly, PDIM isolated from mouse lung tissue displayed the same lengthened mycocerosic acids suggesting that during the infection Mtb experiences comparable build-up of propionyl-CoA (Jain et al., 2007). These data argue strongly that Mtb needs to be able to process propionyl-CoA in vivo, where the carbon source(s) remain to be defined.

While we do not have a full appreciation of the carbon sources utilized by Mtb during infection, there is genetic evidence that Mtb mobilizes and metabolizes cholesterol from the host (Pandey and Sassetti, 2008). Mtb deficient in the cholesterol transporter encoded by mce4 (Mohn et al., 2008; Pandey and Sassetti, 2008) are able to infect macrophages in vitro and mice in vivo, however the ability to express Mce4 is required to sustain the persistent phase of the in vivo infection, and for survival in IFN-γ-activated macrophages. These data are extremely similar to those observed in icl1-deficient Mtb suggesting that cholesterol is metabolized by Mtb at certain phases during infection. It has already been demonstrated that metabolism of cholesterol contributes to the increase in the propionyl-CoA pool (Yang et al., 2009).

A recent paper details a novel switching mechanism under which Mtb can respond to redox fluctuations in the bacterial cytosol by selectively incorporating propionate into the cell wall lipids polyacyltrehalose (PAT), SL-1, PDIM, and triacylglycerol (TAG) (Singh et al., 2009). This regulated utilization of propionate was observed in murine macrophage infections in vitro, and was dictated by the transcriptional regulator WhiB3, which functions by virtue of a thiol-disulfide redox switch. The WhiB3 mutant is resistant to propionate toxicity, which may be due to the increased levels of PDIM produced by this mutant in broth culture and within resting macrophages. Microarray analysis of Mtb in macrophages shows upregulation in expression of WhiB3, as well as genes involved in the synthesis of PAT, SL-1 and TAG (Rohde et al., 2007). Additionally, the generation of energy from fatty acids through βoxidation results in production of NADH, which has the potential to disrupt redox homeostasis. The authors went on to propose that in addition to relieving propionate toxicity by direct incorporation of methylmalonyl-CoA precursers into lipids, any resulting redox imbalance may also be remediated through the use of cell wall lipid synthesis as a sink for reductants generated during lipid breakdown (Singh et al., 2009).

Lipid overload at the site of infection

The link between alterations in lipid metabolism of Mtb during infection is also consistent with the physiological changes observed in the host, both at the level of the macrophage and the granuloma.

Infection of macrophages with Mtb or BCG in vitro causes the induction of foam cell formation (D'Avila et al., 2006; Peyron et al., 2008). Foam cells are the product of dysregulated lipid metabolism whereby cholesterol is esterified and sequestered in intracellular droplets that form in the ER and accumulate within the cell cytosol. The induction of foam cell formation in Mtb-infected macrophages is dependent on stimulation of TLR receptors by Mtb cell wall lipids, predominantly oxygenated mycolic acids present in trehalose dimycolate (TDM) (Bowdish et al., 2009; D'Avila et al., 2006; Peyron et al., 2008).

Recently, we performed microarray analysis on human TB granulomas following isolation by laser-capture microdissection (Kim et al., 2010). Amongst the genes most highly upregulated were several encoding proteins involved in lipid processing and sequestration, most notably the lipid droplet protein adipophilin, ADFP. Immunohistology with antibodies against these proteins demonstrated that they were highly expressed in macrophages subtending the caseous center of the granuloma. Foamy macrophages can be extremely abundant within TB granulomas and are thought to be the source of the caseous debris that accumulates in the granuloma center. We isolated the lipids of the caseum and employed thin-layer chromatography and mass spectrometry to identify the major lipid species as triacylglycerol, cholesterol, cholesterol ester, and lactosylceramide. This lipid profile is consistent with the lipids of the caseum being of host origin, and coming from low-denisty lipoprotein-derived lipids that had been sequestered in foamy macrophages (Kim et al., 2010; Russell et al., 2009a). These data suggest that the generation of foam cells by Mtb could represent a mechanism by which the pathogen could drive the progression of the granuloma towards cavitation and transmission.

Electron-microscopical analysis indicates that Mtb can gain physical access to the lipid droplets within the cell and it has been postulated that this might be a privileged site that would support growth of persistent bacteria within the granuloma through the provision of nutrients and a host cell that is anergic to activating cytokines (Peyron et al., 2008). Modeling this stage of the progression has been problematic because fibrocaseous granulomas are a feature of the human disease that is not generated effectively in mice. However, a recent report describes that mice infected with Mtb and treated sub-optimally with antibiotics to kill replicating bacteria will reactivate and generate granulomas more reminiscent of human caseous granulomas (Hunter et al., 2007). Histopathology revealed focal lesions resembling lipid pneumonia typified by alveoli filled with foamy macrophages. Acid-fast stain demonstrated that these foamy macrophages were the predominant cell type that harbored Mtb bacilli. In the central foci of necrosis Mtb were observed associated with lipid droplets. While these are only preliminary observations, this study may provide a route for generating a murine granuloma that more faithfully reproduces the physiological characteristics of the human TB granuloma. Experimentally, this would be an invaluable tool for understanding both the physiology of granuloma progression and bacterial metabolism within this lipid-laden tissue.

Heterogeneity across the infection

Histological examination of lung tissue from an individual with active TB brings home an extremely significant problem to understanding progression of disease from a persistent infection to active TB. While an immunocompetent individual with active disease will contain cavitated granulomas that spill infectious bacteria into the airways, they are also likely to harbor granulomas in all stages of “development” from containment through to sterilized infection sites, as indicated from studies on higher primates (Lin et al., 2009). It is unclear if there is any difference between the systemic immune response in an individual harboring a controlled, persistent infection, versus one with active disease. Certainly programs attempting to identify systemic biomarkers of disease state have met with extremely limited success (Doherty et al., 2009; Wallis et al., 2009). While this has serious implications for monitoring disease progress, or understanding why one granuloma becomes active while others resolve, it has even greater significance for vaccine development because it implies that the best immune response leads to nothing better than containment. To improve upon this the vaccine would have to exceed the effectiveness of the immune response generated by a natural infection. To date, in animal models, this has not been possible.

In addition to heterogeneity between different granulomas in the same individual, there is also considerable heterogeneity within the granuloma, which offers many different microenvironments for Mtb. While it is proposed that Mtb replicates rapidly and extracellularly upon cavitation of an active granuloma (Kaplan et al., 2003) this has not been confirmed experimentally. Because Mtb is distributed in different sites within the granuloma structure (Ulrichs and Kaufmann, 2006) it remains to be determined which regions are more permissive to bacteria growth and which regions place the bacilli under greatest immune pressure. These data are critical for both understanding drug action, as well as the identification of new, more effective drug targets. Existing drugs show preferential activity against replicating bacteria so if Mtb slows its replication rate or becomes “dormant” it will display an innate resistance to drug activity. The presence of bacteria in different metabolic states likely plays a major role in the need for prolonged treatment (6–9 months) to effectively clear infection. New drugs that exploit targets relevant to bacterial metabolism within the host are required, one such example are the new ATP synthase inhibitors that impact both growing and vegetative bacteria (Andries et al., 2005).

Concluding remarks

Tuberculosis represents a protracted discourse between both host and pathogen that leads to extensive metabolic remodeling in both organisms. The atherosclerotic-like host response within the granuloma leads to lipid sequestration, which likely contributes to the pathology that culminates in cavitation and transmission. In turn, this re-alignment in host metabolism appears to require alterations in Mtb that switches to the utilization of lipids as alternate carbon sources. The metabolic interplay that is emerging in the current literature seems to afford new insights into the pressure points in the life cycle of Mtb, which, hopefully, will lead to new chemotherapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health AI067027, AI057086, AI080651, HL055936, HL100928 (DGR).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature

- Alonso S, Pethe K, Russell DG, Purdy GE. Lysosomal killing of Mycobacterium mediated by ubiquitin-derived peptides is enhanced by autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6031–6036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700036104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andries K, Verhasselt P, Guillemont J, Gohlmann HW, Neefs JM, Winkler H, Van Gestel J, Timmerman P, Zhu M, Lee E, et al. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2005;307:223–227. doi: 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod S, Oschkinat H, Enders J, Schlegel B, Brinkmann V, Kaufmann SH, Haas A, Schaible UE. Delay of phagosome maturation by a mycobacterial lipid is reversed by nitric oxide. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1530–1545. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon C, Dick T. Mycobacterium bovis BCG response regulator essential for hypoxic dormancy. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6760–6767. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.6760-6767.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdish DM, Sakamoto K, Kim MJ, Kroos M, Mukhopadhyay S, Leifer CA, Tryggvason K, Gordon S, Russell DG. MARCO, TLR2, and CD14 are required for macrophage cytokine responses to mycobacterial trehalose dimycolate and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000474. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzostek A, Dziadek B, Rumijowska-Galewicz A, Pawelczyk J, Dziadek J. Cholesterol oxidase is required for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;275:106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier N, Blanc-Potard A, Ehrt S, Piddington D, Riley L, Groisman EA. A parallel intraphagosomal survival strategy shared by mycobacterium tuberculosis and Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1375–1382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Miner MD, Pandey AK, Gill WP, Harik NS, Sassetti CM, Sherman DR. igr Genes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis cholesterol metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5232–5239. doi: 10.1128/JB.00452-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens DL, Horwitz MA. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome interacts with early endosomes and is accessible to exogenously administered transferrin. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1349–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Converse PJ, Karakousis PC, Klinkenberg LG, Kesavan AK, Ly LH, Allen SS, Grosset JH, Jain SK, Lamichhane G, Manabe YC, et al. Role of the dosR-dosS two-component regulatory system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence in three animal models. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1230–1237. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01117-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Avila H, Melo RC, Parreira GG, Werneck-Barroso E, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Bozza PT. Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin induces TLR2-mediated formation of lipid bodies: intracellular domains for eicosanoid synthesis in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;176:3087–3097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb C, Lee CM, Dubey VS, Daniel J, Abomoelak B, Sirakova TD, Pawar S, Rogers L, Kolattukudy PE. A novel in vitro multiple-stress dormancy model for Mycobacterium tuberculosis generates a lipid-loaded, drug-tolerant, dormant pathogen. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V, Delgado M, Vergne I, Master S, De Haro S, Ponpuak M, Singh S. Autophagy in immunity against mycobacterium tuberculosis: a model system to dissect immunological roles of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;335:169–188. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TM, Wallis RS, Zumla A. Biomarkers of disease activity, cure, and relapse in tuberculosis. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30:783–796. x. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JL, Chan J. What's good for the host is good for the bug. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigui W, Bottai D, Majlessi L, Monot M, Josselin E, Brodin P, Garnier T, Gicquel B, Martin C, Leclerc C, et al. Control of M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 secretion and specific T cell recognition by PhoP. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill WP, Harik NS, Whiddon MR, Liao RP, Mittler JE, Sherman DR. A replication clock for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2009;15:211–214. doi: 10.1038/nm.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo Asensio J, Maia C, Ferrer NL, Barilone N, Laval F, Soto CY, Winter N, Daffe M, Gicquel B, Martin C, et al. The virulence-associated two-component PhoP-PhoR system controls the biosynthesis of polyketide-derived lipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1313–1316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn M, Rohde KH, Russell DG, Soldati T. Infection by tubercular mycobacteria is spread by nonlytic ejection from their amoeba hosts. Science. 2009;323:1729–1733. doi: 10.1126/science.1169381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren J, Grewal T, Jackle S, Beisiegel U. Recycling of apolipoprotein E and lipoprotein lipase through endosomal compartments in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42333–42338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homolka S, Niemann S, Russell DG, Rohde KH. Functional genetic diversity among M. tuberculosis clinical isolates: Delineation of conserved core and lineage-specific transcriptomes during intracellular survival. PLoS Pathogens. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000988. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter RL, Jagannath C, Actor JK. Pathology of postprimary tuberculosis in humans and mice: contradiction of long-held beliefs. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Stadthagen G, Gicquel B. Long-chain multiple methyl-branched fatty acid-containing lipids of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: biosynthesis, transport, regulation and biological activities. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Petzold CJ, Schelle MW, Leavell MD, Mougous JD, Bertozzi CR, Leary JA, Cox JS. Lipidomics reveals control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence lipids via metabolic coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5133–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610634104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G, Post FA, Moreira AL, Wainwright H, Kreiswirth BN, Tanverdi M, Mathema B, Ramaswamy SV, Walther G, Steyn LM, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth at the cavity surface: a microenvironment with failed immunity. Infect Immun. 2003;71:7099–7108. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7099-7108.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katti MK, Dai G, Armitige LY, Rivera Marrero C, Daniel S, Singh CR, Lindsey DR, Dhandayuthapani S, Hunter RL, Jagannath C. The Delta fbpA mutant derived from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv has an enhanced susceptibility to intracellular antimicrobial oxidative mechanisms, undergoes limited phagosome maturation and activates macrophages and dendritic cells. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1286–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M-J, Wainwright HC, Locketz M, Bekker L-G, Walther GB, Dittrich C, Visser A, Wang W, Hsu F-F, Wiehart U, et al. Caseation of human tuberculosis granulomas correlates with elevated host lipid metabolism. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000079. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemans JC, Juffermans NP, Florquin S, van Rooijen N, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Verbon A, van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. Depletion of alveolar macrophages exerts protective effects in pulmonary tuberculosis in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:4604–4611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistikow RL, Morton RA, Bartek IL, Frimpong I, Wagner K, Voskuil MI. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosR regulon assists in metabolic homeostasis and enables rapid recovery from nonrespiring dormancy. J Bacteriol. 192:1662–1670. doi: 10.1128/JB.00926-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistikow RL, Morton RA, Bartek IL, Frimpong I, Wagner K, Voskuil MI. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosR regulon assists in metabolic homeostasis and enables rapid recovery from nonrespiring dormancy. J Bacteriol. 2009;192:1662–1670. doi: 10.1128/JB.00926-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PL, Rodgers M, Smith L, Bigbee M, Myers A, Bigbee C, Chiosea I, Capuano SV, Fuhrman C, Klein E, et al. Quantitative comparison of active and latent tuberculosis in the cynomolgus macaque model. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4631–4642. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00592-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PT, Modlin RL. Human macrophage host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwiczak P, Gilleron M, Bordat Y, Martin C, Gicquel B, Puzo G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis phoP mutant: lipoarabinomannan molecular structure. Microbiology. 2002;148:3029–3037. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking JD, North RJ, LaCourse R, Mudgett JS, Shah SK, Nathan CF. Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5243–5248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking JD, Taylor GA, McKinney JD. Immune control of tuberculosis by IFN-gamma-inducible LRG-47. Science. 2003;302:654–659. doi: 10.1126/science.1088063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Orozco N, Touret N, Zaharik ML, Park E, Kopelman R, Miller S, Finlay BB, Gros P, Grinstein S. Visualization of vacuolar acidification-induced transcription of genes of pathogens inside macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:498–510. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney JD, Honer zu Bentrup K, Munoz-Elias EJ, Miczak A, Chen B, Chan WT, Swenson D, Sacchettini JC, Jacobs WR, Jr, Russell DG. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature. 2000;406:735–738. doi: 10.1038/35021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn WW, van der Geize R, Stewart GR, Okamoto S, Liu J, Dijkhuizen L, Eltis LD. The actinobacterial mce4 locus encodes a steroid transporter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35368–35374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805496200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahedzadeh F, Smith DA, Norman RA, Dinadayala P, Murray-Rust J, Russell DG, Kendall SL, Rison SC, McAlister MS, Bancroft GJ, et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ino1 gene is essential for growth and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1003–1014. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Elias EJ, Timm J, Botha T, Chan WT, Gomez JE, McKinney JD. Replication dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in chronically infected mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73:546–551. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.546-551.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Elias EJ, Upton AM, Cherian J, McKinney JD. Role of the methylcitrate cycle in Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism, intracellular growth, and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1109–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C, Shiloh MU. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8841–8848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt NM, Yang X, Fontan P, Kolesnikova I, Smith I, Sampson NS, Dubnau E. A thiolase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for virulence and production of androstenedione and androstadienedione from cholesterol. Infect Immun. 78:275–282. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00893-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RJ, Jung YJ. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey AK, Sassetti CM. Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4376–4380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711159105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HD, Guinn KM, Harrell MI, Liao R, Voskuil MI, Tompa M, Schoolnik GK, Sherman DR. Rv3133c/dosR is a transcription factor that mediates the hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:833–843. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez E, Samper S, Bordas Y, Guilhot C, Gicquel B, Martin C. An essential role for phoP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:179–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron P, Vaubourgeix J, Poquet Y, Levillain F, Botanch C, Bardou F, Daffe M, Emile JF, Marchou B, Cardona PJ, et al. Foamy macrophages from tuberculous patients' granulomas constitute a nutrient-rich reservoir for M. tuberculosis persistence. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000204. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Gagneux S, Deriemer K, Small PM, Barry CE., 3rd The W-Beijing lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis overproduces triglycerides and has the DosR dormancy regulon constitutively upregulated. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2583–2589. doi: 10.1128/JB.01670-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees RJ, Hart PD. Analysis of the host-parasite equilibrium in chronic murine tuberculosis by total and viable bacillary counts. Br J Exp Pathol. 1961;42:83–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson N, Wolke M, Ernestus K, Plum G. A mycobacterial gene involved in synthesis of an outer cell envelope lipid is a key factor in prevention of phagosome maturation. Infect Immun. 2007;75:581–591. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00997-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde KH, Abramovitch RB, Russell DG. Mycobacterium tuberculosis invasion of macrophages: linking bacterial gene expression to environmental cues. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:352–364. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG. Who puts the tubercle in tuberculosis? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:39–47. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG, Cardona PJ, Kim MJ, Allain S, Altare F. Foamy macrophages and the progression of the human tuberculosis granuloma. Nat Immunol. 2009a;10:943–948. doi: 10.1038/ni.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG, Purdy GE, Owens RM, Rohde KH, Yates RM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the four minute phagosome. ASM News. 2005;71:459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG, Vanderven BC, Glennie S, Mwandumba H, Heyderman RS. The macrophage marches on its phagosome: dynamic assays of phagosome function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009b;9:594–600. doi: 10.1038/nri2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad TR, Sherrid AM, Minch KJ, Sherman DR. Hypoxia: a window into Mycobacterium tuberculosis latency. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1151–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvi S, Warner DF, Kana BD, McKinney JD, Mizrahi V, Dawes SS. Functional characterization of a vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonyl pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for propionate metabolism during growth on fatty acids. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:3886–3895. doi: 10.1128/JB.01767-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible UE, Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger PH, Russell DG. Cytokine activation leads to acidification and increases maturation of Mycobacterium avium-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1998;160:1290–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Voskuil MI, Liu Y, Mangan JA, Monahan IM, Dolganov G, Efron B, Butcher PD, Nathan C, et al. Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within Macrophages: Insights into the Phagosomal Environment. J Exp Med. 2003;198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Crossman DK, Mai D, Guidry L, Voskuil MI, Renfrow MB, Steyn AJ. Mycobacterium tuberculosis WhiB3 maintains redox homeostasis by regulating virulence lipid anabolism to modulate macrophage response. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000545. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schaible UE, Russell DG. Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes are accessible to early endosomes and reflect a transitional state in normal phagosome biogenesis. Embo J. 1996;15:6960–6968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger PH, Chakraborty P, Haddix PL, Collins HL, Fok AK, Allen RD, Gluck SL, Heuser J, Russell DG. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263:678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugii S, Reid PC, Ohgami N, Du H, Chang TY. Distinct endosomal compartments in early trafficking of low density lipoprotein-derived cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27180–27189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MC, Chakravarty S, Zhu G, Xu J, Tanaka K, Koch C, Tufariello J, Flynn J, Chan J. Characterization of the tuberculous granuloma in murine and human lungs: cellular composition and relative tissue oxygen tension. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:218–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrichs T, Kaufmann SH. New insights into the function of granulomas in human tuberculosis. J Pathol. 2006;208:261–269. doi: 10.1002/path.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wel N, Hava D, Houben D, Fluitsma D, van Zon M, Pierson J, Brenner M, Peters PJ. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell. 2007;129:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderVen BC, Hermetter A, Huang AY, Maxfield FR, Russell DG, Yates RM. Development of a novel, cell-based chemical screen to identify inhibitors of intraphagosomal lipolysis in macrophages. Cytometry A. 2010 doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20911. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderVen BC, Yates RM, Russell DG. Intraphagosomal measurement of the magnitude and duration of the oxidative burst. Traffic. 2009;10:372–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergne I, Chua J, Deretic V. Tuberculosis toxin blocking phagosome maturation inhibits a novel Ca2+/calmodulin-PI3K hVPS34 cascade. J Exp Med. 2003;198:653–659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergne I, Chua J, Lee HH, Lucas M, Belisle J, Deretic V. Mechanism of phagolysosome biogenesis block by viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4033–4038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409716102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Via LE, Fratti RA, McFalone M, Pagan-Ramos E, Deretic D, Deretic V. Effects of cytokines on mycobacterial phagosome maturation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111 ( Pt 7):897–905. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.7.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Via LE, Lin PL, Ray SM, Carrillo J, Allen SS, Eum SY, Taylor K, Klein E, Manjunatha U, Gonzales J, et al. Tuberculous granulomas are hypoxic in guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2333–2340. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01515-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walburger A, Koul A, Ferrari G, Nguyen L, Prescianotto-Baschong C, Huygen K, Klebl B, Thompson C, Bacher G, Pieters J. Protein kinase G from pathogenic mycobacteria promotes survival within macrophages. Science. 2004;304:1800–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1099384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis RS, Doherty TM, Onyebujoh P, Vahedi M, Laang H, Olesen O, Parida S, Zumla A. Biomarkers for tuberculosis disease activity, cure, and relapse. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:162–172. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters SB, Dubnau E, Kolesnikova I, Laval F, Daffe M, Smith I. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis PhoPR two-component system regulates genes essential for virulence and complex lipid biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:312–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne LG, Sohaskey CD. Nonreplicating persistence of mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:139–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AJ, Linas B, Trevejo-Nunez GJ, Kincaid E, Tamura T, Takatsu K, Ernst JD. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects dendritic cells with high frequency and impairs their function in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:2509–2519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Nesbitt NM, Dubnau E, Smith I, Sampson NS. Cholesterol metabolism increases the metabolic pool of propionate in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3819–3821. doi: 10.1021/bi9005418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates RM, Hermetter A, Russell DG. The kinetics of phagosome maturation as a function of phagosome/lysosome fusion and acquisition of hydrolytic activity. Traffic. 2005;6:413–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates RM, Hermetter A, Taylor GA, Russell DG. Macrophage activation downregulates the degradative capacity of the phagosome. Traffic. 2007;8:241–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates RM, Russell DG. Phagosome maturation proceeds independently of stimulation of toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Immunity. 2005;23:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]