Abstract

This study examines the relationship between having other-sex versus same-sex best friends and antisocial behavior throughout early adolescence. Participants (N = 955) were recruited in 6th grade and followed longitudinally through 7th, 8th, and 11th grades. Participants were 58% ethnically diverse youth and 48% girls. Results indicate that the frequency of other-sex best friendship remained stable from 6th to 7th grade but significantly increased from 8th to 11th grade. Higher rates of concurrent antisocial behavior were related to having other-sex best friends in 6th grade but not in 7th grade. In 8th grade, there was an interaction between friendship and the sex of friends. Boys with only same-sex best friends and girls with other-sex best friends endorsed higher rates of antisocial behavior. Having other-sex best friends predicted antisocial behavior from 6th to 7th grade and 8th to 11th grade, especially for girls. Implications for the development of early adolescent friendship and antisocial behavior are discussed.

Keywords: Early adolescence, Other-sex friendship, Best friends, Antisocial behavior, Peer relations

Introduction

One of the most important social transitions in early adolescence is the formation of other-sex peer relationships (Connolly et al. 2000; Sippola 1999). Prior to the onset of adolescence, boys and girls become socialized primarily within same-sex contexts (Bukowski et al. 2007; Maccoby 1998). During the transition to adolescence, other-sex relationships are important because they represent the merging of two gender cultures into more meaningful relationships. Previous research has examined other-sex friendships in children (de Guzman et al. 2004; Kovacs et al. 1996) and adults (Bleske-Rechek and Buss 2001; Reeder 2003) as they relate to social and emotional development and adjustment. However, research has just begun to examine other-sex relationships in early adolescence, the point at which mixed friendship groups become more salient (Savin-Williams and Berndt 1990) and more time is spent with other-sex peers (Blyth and Traeger 1988; Darling et al. 1999; Feiring 1999). The literature has clearly demonstrated that children and adolescents do indeed have other-sex friendships and best friendships distinct from romantic relationships, that these types of relationships increase during adolescence, and that these relationships are viewed as distinct from same-sex friendships (McDougall and Hymel 2007).

Although many studies have examined the interaction between peer rejection and antisocial behavior over time, few have closely studied the impact that same-sex versus other-sex friendships have on later problem behavior for boys and girls. This study will examine boys' and girls' friendships with same-sex and other-sex peers as predictors of antisocial behavior in middle school and high school.

Friendship

Same-sex friendship dominates the childhood peer socialization experience from preschool through grade school (Gottman 1986; Howes 1988; Maccoby 1990, 1998). Maccoby (1990, 1998) discusses the influences of gender-segregated socialization in childhood, which is apparent as early as at 2 years old, and observes that boys and girls accomplish social adaptation within same-sex friendships. Although preadolescence continues to be characterized primarily by same-sex friendships (Zarbatany et al. 2000), the occurrence of other-sex friendships begins to increase in early adolescence (Blyth and Traeger 1988; Darling et al. 1999; Feiring 1999; McDougall and Hymel 2007). Some studies have demonstrated that young adolescents continue to prefer same-sex peers to other-sex peers (Bukowski et al. 1993; Bukowski et al. 1999), and others suggest that same-sex peer preference declines over time (Sippola et al. 1997). A study by Bukowski and colleagues (1999) supports both seemingly contradictory findings: other-sex and same-sex friends were equally endorsed in general, but best friends were still predominantly same-sex peers. These findings suggest that the number of other-sex friendships does increase during early adolescence, while close friends continue to be typically those of the same sex. This somewhat sudden shift toward other-sex and mixed-sex socialization in early adolescence is a critical social transition, especially considering that friendship is uniquely important to the social, emotional, and behavioral development of these youth.

Although young adolescents prefer same-sex peers, other-sex peers increase in importance over time. Darling et al. (1999) compared the experiences of sixth graders with those of eighth graders in mixed-sex contexts and found an increase in other-sex peer preference across time. They also observed that norms for other-sex relationships were not consistently established until eighth grade. Boys and girls did not differ in their descriptive experiences in mixed-sex groups; both rated mixed-sex contexts as more enjoyable than same-sex-only contexts in eighth grade. This research confirms the increase in the number of other-sex peer relationships and indicates that these relationships are even preferred by the time early adolescents are transitioning into late adolescence.

Given that the importance of other-sex and same-sex friendships changes over the course of early adolescence, it is pertinent to investigate the effects of other-sex friendships spanning this developmental time period. Sroufe and colleagues (1993) demonstrated that socially competent preadolescents did not have other-sex friends, and those with other-sex friends had lower levels of social competence. If other-sex relationships negatively affect social competence, they may be related to social difficulties in early adolescence, as well. Kovacs and colleagues (1996) clarified that the negative effects of having other-sex friends are only present in the absence of same-sex friends.

The question of the impact of other-sex friendships may be better answered by examining sex differences, given that childhood socialization experiences occur in different contexts for boys and for girls. For example, McDougall and Hymel (2007) found that 64% of their sample of 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 12th graders endorsed differences between same-sex and other-sex friendships. These authors demonstrated that conceptions of other-sex and same-sex friendships diverged. Although children endorsed similarities between these types of friendships, early and late adolescents expressed more similarities among same-sex friends and less among other-sex friends. Early and late adolescent participants agreed that the primary function of boys' friendships is to engage in activities. However, these same girl and boy participants differed in their conceptualizations of girls' friendship: The girls indicated more intimacy in these relationships than in their other-sex friendships, whereas boys did not endorse intimacy as a stronger feature in girls' relationships than in boys'. Friendship in general may serve different functions for boys than for girls, and other-sex relationships are likely characterized by their individual expectations and needs as two friendship cultures are merged.

Friends and Antisocial Behavior

Peer relationships are highly influential in the development and course of antisocial behavior in adolescence, and close friendships may be especially important (Pedersen et al. 2007). For example, Dishion and colleagues have shown that, in the context of best friend interactions, youth support each other in the development of deviant behavior through deviant talk, laughter, and other nonverbal supports for antisocial behavior (Dishion et al. 2004; Piehler and Dishion 2007). Similarly, Laird et al. (1999) found that positive friendship qualities moderated the antisocial behavior of early adolescent boys and girls who perceived their best friends as engaged in antisocial behavior. They concluded that the same qualities that contribute to successful close friendships are those that provide a support structure for the development and maintenance of antisocial behavior. This finding makes sense given that friendship follows a developmental sequence that allows for more emphasis on abstract features of friendship (e.g., intimacy, loyalty) for boys and girls in adolescence compared with those in childhood (Bigelow and LaGaipa 1980; McDougall and Hymel 2007). Because girls tend to value close relationships characterized by intimacy (Bukowski et al. 1994; McDougall and Hymel 2007), they may be especially influenced by antisocial peers. While fulfilling a need for intimacy, girls could be particularly susceptible to encouragement toward antisocial behavior when it is enacted as part of maintaining a close relationship.

Although there appears to be little difference between boys and girls regarding antisocial behavior prior to kindergarten (Keenan et al. 1999; Keenan and Shaw 1997), apparent sex differences relevant to behavior emerge and are substantiated empirically in adolescence. During adolescence, girls begin to demonstrate antisocial behaviors comparable to those of their male counterparts. It seems that pubertal onset, which occurs in early adolescence, contributes to various forms of psychological maladjustment for girls, including antisocial behavior. Reaching this biological transition earlier than their peers has been found to be particularly challenging for girls. Early menarche has been found to be a risk factor for behavior problems if girls have other-sex peer relationships (Caspi et al. 1993). The mechanism for adolescent development of antisocial behavior for girls in particular has been the subject of debate. Moffitt and colleagues (Moffitt, 2006) asserted that boys and girls exhibit different developmental trajectories and etiological profiles of antisocial behavior. In their model, boys tend toward child-onset antisocial behavior because of certain risk factors, and girls typically begin these behaviors in adolescence. Silverthorn and Frick (1999) contended that onset trajectories for boys and girls have less to do with differential risk factors and more to do with gender differences. Although girls are subject to the same risk factors as their male counterparts, they do not express their maladjustment externally until early adolescence, because of gender socialization.

Regardless of the specific etiology, girls tend to demonstrate increases in antisocial behavior during the time the number of other-sex friendships increases in early adolescence. This may be partially explained by the type of other-sex friends girls are attracted to in early adolescence. Bukowski et al. (2000) found that girls entering middle school were more attracted to boys who demonstrated higher levels of aggression. In other research, boys were also found to be more attracted to more dominant male peers as well as to aggressive female peers. The authors concluded that the transition into early adolescence is characterized by a “maturity gap” in which physical development moves toward adulthood more quickly than does socioemotional development (Moffitt 2006). This desire to move toward adulthood compels boys and girls to be attracted to those who demonstrate more power and adhere most strongly to traditional male sex roles. This study implies that both girls and boys are more likely to engage with more aggressive and deviant boys upon entering early adolescence.

Associating with deviant peers has been related to the onset of antisocial behavior in adolescence, even for those who have not demonstrated childhood antisocial behaviors (Capalidi and Patterson 1994). For boys, deviancy of best friends has been demonstrated to be a predictor of delinquency in early adolescence despite controlling for preadolescent delinquency (Vitaro et al. 2000). Pleydon and Schner (2001) examined delinquent and nondelinquent girls and their relationships with their same-sex best friend and their peer group. The authors found no differences between delinquent and nondelinquent same-sex best friendships in terms of intimacy, companionship, conflict, help, loyalty, security, and closeness. However, there were differences between the two peer groups: delinquent girls reported more peer pressure and a greater number of other-sex peers than did nondelinquent girls. Similarly, recent research found that girls who have more other-sex friends engaged in higher levels of serious violence, and that this effect increased in proportion to the number of other-sex friends in their friendship network (Haynie et al. 2007). This same study demonstrated opposite findings for boys. Rates of serious violence were reduced for boys who had other-sex friends, and the proportion of other-sex friends in their friendship networks did not influence these outcomes.

Rationale for the Current Study and Hypotheses

Our study addresses several gaps in the literature by examining other-sex friendship in early adolescence and the relationship between friends and antisocial behavior. First, we replicate previous findings that the number of other-sex friendships increases throughout early adolescence. We specifically investigate the frequency of other-sex best friendship across sixth, seventh, and eighth grade. Second, we investigate the effects of having other-sex versus same-sex best friends on antisocial behavior in early adolescence, which had not been studied previously. Specifically, this study examines the relationship between the sex of best friends and antisocial behavior concurrently (within each grade) and longitudinally. We predicted that having other-sex best friends would influence the rate of antisocial behavior over time in different ways for boys than for girls. It was expected that girls who have other-sex best friends would show increased rates of antisocial behavior compared with girls who have same-sex-only best friends. Conversely, it was expected that boys who endorsed girls as best friends would show lower rates of both concurrent and subsequent antisocial behavior.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study included 998 ethnically diverse young adolescents enrolled in three public middle schools in a Pacific Northwest metropolitan area. The sample comprised two cohorts recruited and assessed beginning in the 6th grade. Cohort 1 (n = 676) was recruited and initially assessed during the 1996–1997 academic year, and Cohort 2 (n = 323) was recruited and initially assessed during the 1998–1999 academic year. Participants were randomly assigned at the individual level into a treatment or control group as a part of a larger longitudinal study that targeted at-risk and high-risk youth with a family-centered, school-based intervention to reduce substance use (Project Alliance; Dishion and Kavanagh 2003). Data were collected on each youth in the study from 6th to 11th grade, with an approximate 83% retention in the sample by the last wave of data collection. Our study included all intervention (n = 498) and control (n = 500) participants who endorsed having best friends. Data were collected on each youth in the study from 6th to 11th grade, with an approximate 83% (n = 832) retention in the sample by the last wave of data collection. A small percentage (about 12%) of these students were concurrently receiving a selected intervention (n = 115) during the course of this study aimed at reducing substance use and related risk factors. Results of the intervention are published in Connell et al. (2007). Participants were reimbursed $10.00 per hour for participating in any aspect of this research project.

Fifty-two percent of the participants identified as male and 48% identified as female. The participants self-identified as European American (42.5%, n = 385), African American (29%, n = 271), multiethnic (11.1%, n = 69), Latino/Latina (6.9%, n = 59), Asian American (5.3%, n = 43), American Indian (2.1%, n = 19), Pacific Islander (.9%, n = 7), and other (2.2%, n = 18).

Procedure

Measurements included a demographic questionnaire, sociometric peer nomination, and adolescent self-report of antisocial behavior. Data were collected in the school setting once per year during the winter in 6th, 7th, and 8th grades for sociometric data and 6th, 7th, 8th, and 11th grades for antisocial behavior.

Measures

Friendship

Participants were asked to complete the Peer Nominations and Ratings survey (Coie et al. 1995b) once per year in sixth, seventh, and eighth grade. This survey includes a list of all student participants in the respondents' same grade in alphabetical order. Participants were instructed to indicate their three best friends for one task (Best Friends). For the purpose of our study, participants who indicated all same-sex best friends are considered the “same-sex-only” group, and those indicating at least one other-sex best friend of three are considered the “other-sex” group.

Antisocial Behavior

The scale measuring antisocial behavior was included in the Community Action for Successful Youth (Biglan et al. 1994), which is a self-report questionnaire administered once per year in 6th, 7th, 8th, and 11th grades. Antisocial behavior was assessed using a scale of six items measuring the frequency of delinquent and antisocial behaviors (e.g., stealing, lying, spending time with gang members). These items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale, which ranged from never to more than 20 times per month. Internal consistency was determined acceptable at all measurement time points: 6th grade, α = .83; 7th grade, α = .84; 8th grade, α = .77; and 11th grade, α = .67. We have used the Antisocial Behavior scale from this measure to predict both later risk and deviant friendship patterns in prior research (Piehler and Dishion 2007; Stormshak et al. 2005).

Results

This study examined the relationship between having other-sex versus same-sex-only best friends and antisocial behavior throughout early adolescence. First, descriptive analyses were used to examine the rates of having other-sex versus same-sex-only best friends, as well as the percent of boys and girls endorsing other-sex and same-sex peers with whom they would most like to spend time. Chi-square analyses were then used to determine significant differences in the number of other-sex versus same-sex-only best friends across grades. Concurrent analyses refer to the relationship between having other-sex versus same-sex-only best friends and antisocial behavior within each grade. Regression analyses and ANOVA were used to examine antisocial behavior for boys and girls endorsing other-sex or same-sex-only best friends in sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. Regression analyses and structural equation modeling were used to analyze predictive outcomes of antisocial behavior based on having other-sex versus same-sex-only best friends.

Friendship (Other-sex versus Same-sex Only)

Best Friendship

Our study examined the frequency of other-sex versus same-sex best friendship throughout early adolescence. Other-sex best friends were endorsed by 14% (n = 136) of the sixth graders, 16% (n = 114) of the seventh graders, and 21% (n = 127) of the eighth graders. Chi-square analyses indicate no significant differences between the proportion of other-sex best friends in sixth grade and seventh grade, χ2 (1, 683) = .157, p = .77. However, significant differences were found between seventh grade and eighth grade, χ2 (1, 548) = 30.413, p = .000. These results support the hypothesis that the frequency of other-sex best friendship increases during the course of early adolescence.

Sex Differences

We compared the percentage of boys and girls who had other-sex best friends across early adolescence. Other-sex best friends were endorsed by 16% (n = 78) of the boys in sixth grade, 15% (n = 55) of the boys in seventh grade, and 21% (n = 65) of the boys in eighth grade. Comparatively, other-sex best friends were endorsed by 13% (n = 58) of the girls in sixth grade, 17% (n = 57) of the girls in seventh grade, and 21% (n = 61) of the girls in eighth grade. Chi-square analyses indicate no significant differences in the percent of other-sex best friends between girls and boys in sixth grade, χ2 (1, 949) = 1.785, p = .181; seventh grade, χ2 (1, 703) = .719, p = .40; or eighth grade, χ2 (1, 599) = .000, p = 1.00.

The percent of other-sex best friendship was also examined relevant to each sex. Chi-square analyses indicate no significant differences in sex of best friends between girls in sixth grade and girls in seventh grade, χ2 (1, 325) = .205, p = .65 or between boys in sixth grade and boys in seventh grade, χ2 (1, 354) = .708, p = .40. However, there were significant differences between girls in seventh and girls in eighth grade, χ2 (1, 263) = 14.617, p = .000 and between boys in seventh and boys in eighth grade, χ2 (1, 276) = 17.835, p = .000. The within-sex results for boys and for girls are similar to their combined results. For each, there appears to be a similar rate of other-sex best friendship in sixth and seventh grades but a marked increase in eighth grade.

Concurrent Analyses

Next, we examined the relationship between best friendship and antisocial behavior in the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. Regression analysis and ANOVA were used to analyze main effects, and independent samples t-tests were used to determine within-sex differences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of sex of best friends on antisocial behavior in 6th, 7th, and 8th grades

| df | F | η2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th Grade | ||||

| Friends | 1 | 5.71** | .006 | .02 |

| Sexa | 1 | 3.44* | .004 | .06 |

| Sex friends* | 1 | 1.23 | .001 | .27 |

| Error | 944 | (.320) | ||

| 7th Grade | ||||

| Friends | 1 | 1.17 | .002 | .28 |

| Sex | 1 | 1.68 | .003 | .20 |

| Sex friends* | 1 | .04 | .000 | .83 |

| Error | 600 | (.360) | ||

| 8th Grade | ||||

| Friends | 1 | .081 | .000 | .78 |

| Sex | 1 | .062 | .000 | .80 |

| Sex friends* | 1 | 4.77* | .010 | .03 |

| Error | 600 | (.360) |

Note: Values enclosed in parentheses represent mean square errors

p ≤ .06

p ≤ .05

An independent samples t-test indicates girls with other-sex best friends scored higher in antisocial behavior than did girls with same-sex-only best friends, t = −2.38, p = .38; no significant differences were found for boys

Sixth Grade

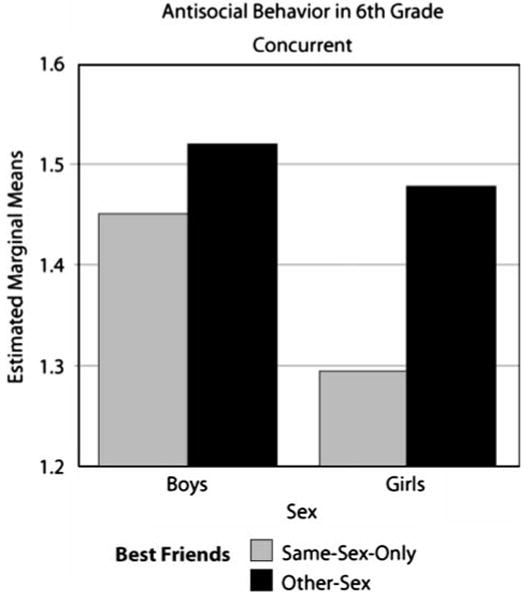

Results presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1 indicate that in sixth grade the extent of antisocial behavior was significantly greater for those with other-sex best friends than for those with same-sex-only best friends for boys and girls overall, F = 5.71, p = .02. A near effect for sex was found, with boys scoring higher than girls in antisocial behavior overall, F = 3.44, p = .06; however, this effect was only moderately significant. An independent samples t-test indicated that girls with other-sex best friends scored higher in antisocial behavior than did girls with same-sex only best friends, t = −2.38, p = .02. Sex of best friends was not significantly related to antisocial behavior for boys, t = −.88, p = .38. These results indicate that having other-sex best friends was related to antisocial behavior in sixth grade for all participants. Among the girls, antisocial behavior was related to having other-sex best friends, whereas sex of best friends was not related to antisocial behavior for boys.

Fig. 1.

Rates of antisocial behavior in 6th grade for boys and for girls endorsing same-sex-only or other-sex best friends

Seventh Grade

In seventh grade, the sex of best friends was not related to antisocial behavior for boys or girls, F = 1.168, p = .28. Significant effects for sex were also not found, F = 1.677, p = .20. Although sex of best friends and sex of study participant did not seem to significantly impact antisocial behavior in seventh grade, the general pattern looked similar to that of sixth grade.

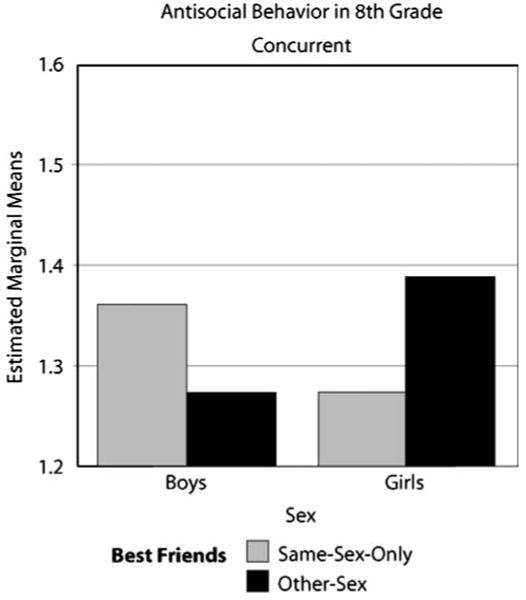

Eighth Grade

Results in eighth grade indicate no significant effects for sex of best friends on antisocial behavior, F = .081, p = .776 or sex of study participant, F = .062, p = .80. However, a significant interaction for sex of best friends and antisocial behavior was found, F = 4.77, p = .03 (see Table 2 and Fig. 2). Boys with same-sex-only best friends scored higher on antisocial behavior than did boys with other-sex best friends. Conversely, girls endorsing other-sex best friends scored higher on antisocial behavior than did girls who indicated same-sex-only best friends. An independent samples t-test was not significant for boys' best friendship, t = 1.22, p = .23 or for girls' best friendship, t = −1.59, p = .12. This interaction demonstrates differential effects of the sex of best friends on antisocial behavior for boys and girls in the eighth grade. Boys endorsing same-sex-only best friends and girls endorsing other-sex best friends indicate higher rates of antisocial behavior.

Table 2.

Antisocial behavior predicted by friendship across grades

| 7th Grade ASB | 8th Grade ASB | 11th Grade ASB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| 6th Grade friendship | 4.98*a | .03 | .014 | .90 | .85 | .47 |

| 7th Grade friendship | – | – | 1.61 | .19 | 1.03 | .38 |

| 8th Grade friendship | – | – | – | – | 3.91* | .05 |

p ≤ .05

A main effect was found for sex, with boys scoring significantly higher than girls, F = 3.82, p = .03

Fig. 2.

Rates of antisocial behavior in 8th grade for boys and for girls endorsing same-sex-only or other-sex best friends

Predictive Analyses

Finally, we examined whether sex of best friends was related to antisocial behavior longitudinally. Regression analysis and ANOVA were used to determine group differences and main effects (see Table 2).

Sixth Grade Predictions

Results indicated that having other-sex best friends in 6th grade is associated with antisocial behavior in 7th grade, F = 4.98, p = .03, but not in 8th grade, F = .014, p = .90 or 11th grade, F = .85, p = .47. In 7th grade, boys scored significantly higher on antisocial behavior than did girls, F = 3.82, p = .03, but no effects were found for 8th grade, F = 2.34, p = .13 or 11th grade, F = .52, p = .47. These results suggest that sex of best friends in 6th grade is only proximally related to antisocial behavior and does not predict later antisocial behavior.

Seventh Grade Predictions

Results indicate that 7th grade other-sex best friendship is not associated with antisocial behavior in 8th grade, F = 1.61, p = .19 or in 11th grade, F = 1.03, p = .38 (Table 2). Main effects for sex on antisocial behavior were not found for 8th grade, F = 1.79, p = .18 or 11th grade, F = 1.17, p = .28. These results are also consistent with the potential developmental shift between 7th and 8th grade.

Eighth Grade Predictions

Results indicate that 8th grade other-sex friendship is associated with antisocial behavior in 11th grade, F = 3.91, p = .05 (Table 2). Main effects for sex were not found, F = .717, p = .40. These results demonstrate that the sex of best friends in 8th grade is related to antisocial behavior in 11th grade.

Taken together, these results indicate similar relationships between sex of friends and antisocial behavior during 6th and 7th grade, and they are not predictive of future behavior. Antisocial behavior in 7th grade was related to having had other-sex best friends in 6th grade, but having had 6th or 7th grade other-sex best friends did not predict antisocial behavior in the 8th or 11th grade. However, other-sex friendship in 8th grade was predictive of 11th grade antisocial behavior, with other-sex friendship predicting antisocial behavior for both girls and boys.

Developmental Model

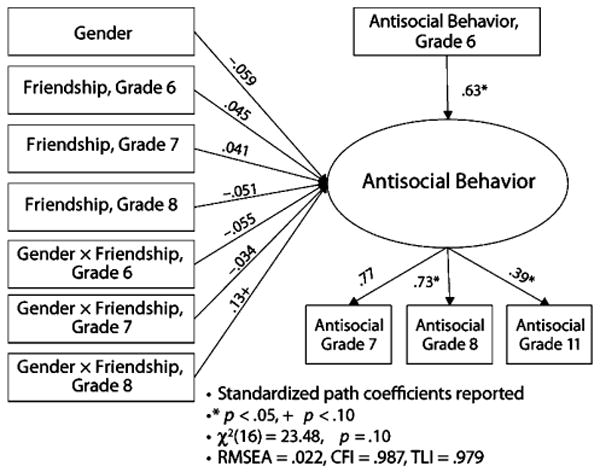

Given the significant pattern of results presented earlier, we examined the interaction between sex and friendship on antisocial behavior within one model that accounted for both gender as well as time, using structural equation modeling. We began by building a latent construct of antisocial behavior using 6th grade antisocial behavior as a covariate to control for prior levels. We tested both the direct effects of same-sex and other-sex friendship as well as the interaction between friendship and gender. Next, we tested the models separately for boys and for girls.

Full Model

We examined the path coefficients for friendship at each grade level on antisocial behavior, as well as the interactions between sex and friendship on antisocial behavior (see Fig. 3). The antisocial behavior latent construct included antisocial behavior measured during 7th, 8th, and 11th grades controlling for 6th grade antisocial behavior. We found that antisocial behavior in 6th grade was significantly related to later antisocial behavior (.63, p < .05); however, gender was not related to antisocial behavior. The overall fit of the model was good, χ2 (16) = 23.48, p = .10, RMSEA = .022, CFI = .987, TLI = .979.

Fig. 3.

Full model: Friendship and gender predicting antisocial behavior

Friendship status (same vs. other-sex friends) in 6th, 7th, and 8th grades was not significantly related to antisocial behavior (.045, p > .05; .041, p > .05; and −.051, p > .05, respectively). Similarly, the interaction between sex of participant and friendship in relation to antisocial behavior was also not significant in any grade; however, there was a trend toward significance in 8th grade (−.055, p > .05; −.034, p > .05; and .13, p < .10).

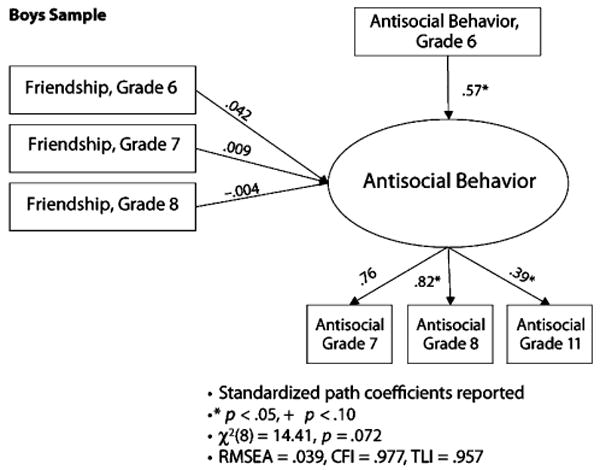

Sex Differences

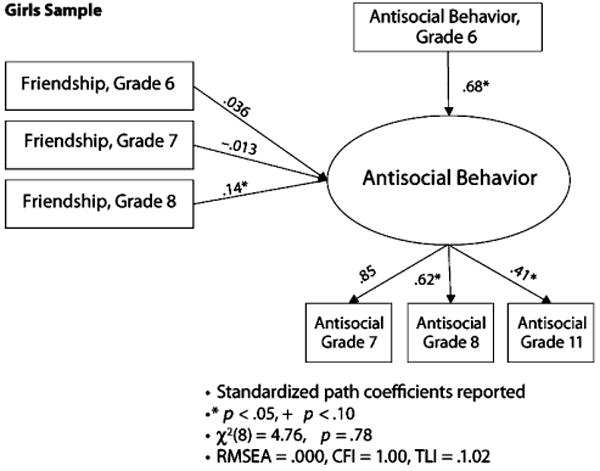

In order to further understand the interaction terms in the full model, we next tested boys and girls separately in two different models. For boys, we found results that paralleled the full model (see Fig. 4). The model for the boys was a good fit, χ2 (8) = 14.41, p = .072, RMSEA = .039, CFI = .977, TLI = .957. Friendship in 6th, 7th, and 8th grades was not related to antisocial behavior (.042, p > .05; .009, p > .05; and −.004, p > .05, respectively). The model for the girls was also a good fit, χ2(8) = 4.76, p = .78, RMSEA = .000, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.02. Friendships in 6th and 7th grades were not significantly related to antisocial behavior (−.036, p > .05 and −.013, p > .05, respectively). However, 8th grade friendship was significantly related to antisocial behavior (.14, p < .05), suggesting that having other-sex best friends in 8th grade was related to antisocial behavior for girls (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Friendship as a predictor of antisocial behavior for boys

Fig. 5.

Friendship as a predictor of antisocial behavior for girls

Discussion

The current findings support the theory that same-sex and other-sex friendships influence developmental outcomes differently for boys and girls. This study sought to examine the relationship between having other-sex versus same-sex best friends and antisocial behavior across early adolescence. We examined the rates of same-sex and other-sex friendships throughout early adolescence. Although the incidence of other-sex best friends did not increase between 6th and 7th grade, adolescents endorsed a significant increase in other-sex best friends in 8th grade compared to in 7th grade. We found that having other-sex best friends was related to concurrent antisocial behavior for boys and girls in 6th grade, but not in 8th grade. In 8th grade, we found an interaction between sex (boys versus girls) and sex of best friends—having other-sex best friends in 8th grade was related to increased antisocial behavior for girls, whereas having same-sex-only best friends was related to increased antisocial behavior for boys. We also found that having other-sex versus same-sex-only best friends predicted only proximal outcomes of antisocial behavior from 6th to 7th grade. However, having other-sex best friends in 8th grade predicted future antisocial behavior in 11th grade, particularly for girls. These findings expand previous research demonstrating that other-sex relationships increase in frequency and change throughout adolescence in different ways for boys than for girls. These data suggest a critical developmental period in early adolescence for the increase in number of other-sex best friendships (i.e., between 7th and 8th grades) as well as the influence these new peers may have on developmental outcomes.

Friendship

Participants endorsed having other-sex best friends at a similar rate during both sixth and seventh grades. However, an increase in the number of other-sex best friends was statistically significant during eighth grade. This trend was similar for boys and girls across grades, and no significant differences were found between the sexes in any grade. These results support previous findings that although early adolescents initially prefer same-sex best friendships, the number of other-sex best friendships increases over time (Bukowski et al. 1999). Our study expands this line of research by demonstrating that having other-sex best friends becomes more important and frequent over time, especially during the transition between seventh and eighth grades. The meaning of these relationships, however, differs for boys and for girls.

Antisocial Behavior

Examination of the influence of having other-sex versus same-sex best friends on antisocial behavior in each grade (concurrently) and on subsequent antisocial behavior (predictively) revealed that having other-sex best friends was significantly associated with higher rates of antisocial behavior for both boys and girls during sixth grade. It was interesting and unexpected to find that having other-sex best friends influenced antisocial behavior similarly for both boys and girls in this grade. Perhaps this finding is reflective of previous research demonstrating that girls are attracted to more aggressive boys and boys are attracted to both aggressive boys and girls upon entry to middle school (Bukowski et al. 2000).

A different pattern of antisocial behavior emerged in eighth grade, however, where we found a significant interaction: boys with same-sex-only best friends and girls with other-sex best friends demonstrated higher rates of antisocial behavior. This interaction supported the hypothesis that having other-sex best friends would affect antisocial behavior differentially for boys and for girls, although this influence was not present until eighth grade. These results were supported in the subsequent structural model, which suggested that girls who had other-sex best friends in eighth grade also demonstrated higher rates of antisocial behavior. The results suggest a developmental shift that occurs between the seventh and eighth grades that affects boys and girls differently. Contrary to previous research showing that boys demonstrate higher rates of antisocial behavior than do girls overall, we found one only moderately significant difference, based on sex, between boys and girls in sixth grade. Our study demonstrates that the sex of best friends is more influential on antisocial behavior outcomes than is sex alone, although this influence of friends on later behavior is stronger for girls than for boys.

This study demonstrates that other-sex relationships and extent of antisocial behavior change over the course of early adolescence, and these trajectories are related to different outcomes for boys than for girls. In sixth grade, girls with other-sex best friends endorsed statistically significant higher rates of antisocial behavior than did girls with same-sex-only best friends. Meanwhile, having other-sex versus same-sex-only best friends did not affect the rate of antisocial behavior for boys. Girls also endorsed higher rates of antisocial behavior in eighth grade if they had other-sex best friends, compared with girls indicating same-sex-only best friends. Conversely, boys endorsed lower rates of antisocial behavior if they had other-sex best friends, compared with boys who indicated same-sex-only best friends. These results support the hypothesis that having other-sex best friends may be a protective factor for boys and a risk factor for girls. However, this differentiation does not seem to emerge until eighth grade. Our study findings are consistent with previous literature, suggesting differential outcomes of other-sex friendship on violent behavior and aggression (Haynie et al. 2007).

It is also important to consider the peer socialization processes in which children who are exposed to same-sex relationships tend to exhibit greater sex-typed behaviors (Martin and Fabes 2001). It follows that boys who spend most of their time with close male friends may be more likely to exhibit competition, dominance, and antisocial behaviors, a premise that has been suggested by recent reviews of research regarding sex differences in peer processes (Rose and Rudolph 2006). A similar pattern may exist for girls, with less aggression in the context of same-sex relationships. These findings are consistent with the research on dyadic interaction patterns of girls and boys with same-sex peers, which suggests that antisocial boys engage in high levels of deviant talk with their peers, and girls engage in less deviant talk than do boys (Piehler and Dishion 2007). Taken together, these findings suggest that antisocial boys negatively influence the behavior of both other boys and girls.

It also might be useful to consider sex differences in these trajectories and to identify sensitive periods of risk and resilience during this dynamic period of development. For example, early-maturing girls have been found to be more susceptible to peer pressure from older peers and boys (Caspi et al. 1993). Our study demonstrates that the effects of other-sex best friendship are not purely differentiated by sex, but also function within a developmental continuum throughout early adolescence, with a marked change in 8th grade. Because during adolescence boys tend to exhibit antisocial behavior earlier than do girls, it is possible that as girls begin to engage in more antisocial behavior in 8th grade, they either become close friends with more antisocial boys or that by having more close relationships with boys, they are exposed to more opportunities to engage in antisocial behavior. In addition, because relationships with boys tend to focus on engaging in activities, and relationships with girls tend to incorporate more aspects of emotional support and intimacy (McDougall and Hymel 2007), it is possible that having female best friends is protective for boys in that they gain emotional support and may be less likely to engage in externalizing behaviors. Clearly, boys and girls follow different trajectories that may be a function of both antisocial behavior development and different reasons for seeking out close other-sex friends.

Perhaps the most important conclusion drawn from our longitudinal findings is that there is a critical period in adolescent social and antisocial development that occurs at around 8th grade that seems to be distinct from that of the previous 2 years in early adolescence. Antisocial behavior outcomes were shown to be proximally influenced by the sex of best friends and seem to indicate a developmental shift sometime between 7th and 8th grades. This is evidenced by the similar patterns of antisocial behavior found in 6th and 7th grades that are not evident in 8th grade. In 6th grade, having other-sex best friends was predictive of 7th grade antisocial behavior but not 8th or 11th grade antisocial behavior. These findings illustrate developmental similarity among 6th and 7th graders in terms of how the sex of best friends influences antisocial behavior. Meanwhile, the sex of best friends in 8th grade was predictive of longer lasting future outcomes of antisocial behavior. This is evidenced by our findings that the sex of best friends in 8th grade predicted outcomes of antisocial behavior in 11th grade. In aggregate, these results seem to demonstrate that 8th grade may be a critical transitional period in social relationships, specifically in terms of the long-term influence of other-sex and same-sex friendships on antisocial behavior. Relationships in early adolescence tend to be highly mutable (Bukowski et al. 1994; Savin-Williams and Berndt 1990), which might be related to our findings that predict only concurrent and proximal antisocial outcomes based on friendship. In addition, the level of stability in friendships may be associated with the level of antisocial behavior in that higher instability could be related to increased antisocial behavior.

Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of this study is the lack of qualitative information about the relationships. For example, it is not possible to distinguish between platonic friendship, romantic relationship, or a combination of these types of relationships. It could be informative to investigate the type of relationships endorsed and to explore factors in those relationships, because having had other-sex friendships in early adolescence has been linked to having more stable and more intimate other-sex romantic relationships in middle and late adolescence (Feiring 1999) and in midlife (Möller and Stattin 2001). It would be important to understand the type, quality, and course of other-sex relationships. In terms of risk factors, perhaps those in close other-sex friendships during early adolescence are more likely to become involved in other-sex romantic relationships earlier and to potentially engage in risky sexual behaviors earlier. Brendgen et al. (2002) found that having a romantic other-sex partner in early adolescence was related to poorer behavioral adjustment if those participants were also unpopular with their same-sex peers. Pubertal status may also impact the development of same-sex versus other-sex friendships at this age, and a measure of puberty would have strengthened this study. In addition to examining risk factors, future directions in research could further investigate the positive aspects of other-sex relationships. For example, comfort in mixed-sex contexts has been related to positive self-perceptions for girls, and time spent with those of the other sex has been related to positive self-perceptions for boys (Darling et al. 1999).

Another potential future research consideration not addressed in this study is the popularity and rejection status of the participants, which so far has produced mixed results in the literature. Previous research has demonstrated the relationship between antisocial behavior and rejection by peers (Coie and Dodge 1998; Laird et al. 2001), but there is no information about the interactions among other-sex relationships, popularity status, and antisocial behavior. In addition, our study included sociometric ratings of other students in their same grade only who were also participating in the study. Therefore, the methodology of our study did not allow for investigation of older peer influence on younger friends, which might indicate sex differences. Previous research has indicated that older boys influence the extent of antisocial behavior of younger girls (Caspi et al. 1993).

In addition, our study did not address friendship stability, which may be related to antisocial behaviors in various ways. For example, rejection by peers has been shown to be related to association with deviant peers and to antisocial behavior. Rejection by peers in childhood contributes to the development of antisocial behavior in adolescence, even when controlling for baseline levels of aggressive behavior (Coie et al. 1995a). Girls who have close other-sex friends may be particularly vulnerable to developing antisocial behaviors if they have been rejected by same-sex friends, and are thus potentially influenced by male friends who have been engaging in antisocial behavior longer. In addition, girls who engage in relational aggression tend to be rejected by their peers (Crick and Bigbee 1998). Laird and colleagues (2001) demonstrated that childhood rejection by peers and greater involvement with antisocial peers were predictive of antisocial behavior in early adolescence, although effects of sex differences were not detected in the study. Their study indicated that rejection by peers, but not association with deviant peers, was related to later antisocial behavior when controlling for externalizing behaviors. Yet another study demonstrated that developmental trajectories differed for male and for female children. Boys with high trajectories for antisocial behavior were rejected by peers and had more deviant peer associations, and girls had fewer deviant peer associations but were equally likely to be rejected at a moderate antisocial behavior trajectory (van Lier et Al. 2005). Given these findings, it is possible that rejection by peers could influence boys and girls differently in terms of antisocial behavior independent from deviant peer affiliation. Furthermore, it would be important to examine the specific effects of same-sex peer rejection as it relates to both having close other-sex friends and demonstrating antisocial behavior. Future research could integrate the stability, popularity status, rejection by peers, and course of other-sex peer relationship factors as they relate to antisocial behavior into a more comprehensive investigation of peer networks.

The antisocial construct in this study was a composite of both covert and overt antisocial behaviors, which did not allow for differences in antisocial presentation to be examined. Related to this concern is the lack of information about antisocial behavior prior to sixth grade. Another limitation is that antisocial behavior was measured by means of adolescent self-report, which doesn't provide the rigor of multimethod measurement or allow for comparison across contexts. Furthermore, it would be important while examining friendship to also consider relational or social aggression, which was not measured in our study but consistently remains an important social process for female relationships and could contribute to aforementioned factors of rejection and one unique reason for forming other-sex close friendships.

As with all longitudinal research, attrition is one of the most salient threats to validity. In our study, approximately 83% of the sample was retained over the 5-year data collection period. Although this is a high retention rate for longitudinal research, the reasons for attrition in our study are not known. When investigating antisocial behavior, attrition can impact predictive results, because adolescents who move in and out of schools may be those who demonstrate higher rates of antisocial behavior. When a research project similar to our study was conducted in another school district in the Northwest more than half of those who moved continued to seek services, indicating that these individuals experienced greater difficulties, perhaps as a function of changing schools (Stormshak et al. 2005). Future longitudinal research of this nature should investigate attrition characteristics.

In summary, same-sex and other-sex friendships are important predictors of antisocial behavior in early adolescence. Girls are particularly susceptible to negative outcomes associated with other-sex friendships during the transition from early to late adolescence. Future research should continue to explore the longitudinal relationships between same-sex and other-sex friendships, problem behavior, and adolescent development. Further examination of other-sex versus same-sex friendships and their relationship to later problem behavior will inform specific prevention and intervention strategies, including specific strategies for boys and for girls, with the goal of reducing adolescent problem behavior and promoting adolescent success.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a larger project directed by principle investigator Thomas Dishion, Ph.D., and supported by grant DA 07031 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Author Biographies

Cara Arndorfer is a doctoral candidate in counseling psychology at the University of Oregon. Her research interests include adolescent development and peer relationships. Clinical interests include the transition to early adulthood, eating disorders, and trauma.

Elizabeth Stormshak is an associate professor in the College of Education and the co-director of the Child and Family Center, both at the University of Oregon. Her research interests include prevention of antisocial behavior with at-risk youth, and peer and sibling relationships.

Contributor Information

Cara Lee Arndorfer, Email: carndorf@uoregon.edu.

Elizabeth A. Stormshak, Email: bstorm@uoregon.edu.

References

- Bigelow BJ, LaGaipa JJ. The development of friendship values and choice. In: Foot H, Chapman A, Smith J, editors. Friendship and social relations in children. New York: Wiley; 1980. pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Metzler CW, Ary DV. Increasing the prevalence of successful children: The case for community intervention research. The Behavior Analyst. 1994;17:335–351. doi: 10.1007/BF03392680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleske-Rechek AL, Buss DM. Opposite-sex friendship: Sex differences and similarities in initiation, selection, and dissolution. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(10):1310–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Traeger C. Adolescent self-esteem and perceived relationships with parents and peers. In: Salzinger S, Antrobus J, Hammer M, editors. Social networks of children, adolescents, and college students. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D, Bukowski WM. Same-sex peer relations and romantic relationships during early adolescence: Interactive links to emotional, behavioral, and academic adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48(1):77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Brendgen M, Vitaro F. Peers and socialization: Effects on externalizing and internalizing problems. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 355–381. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Gauze C, Hoza B, Newcomb AF. Differences and consistency in relations with same-sex and other-sex peers during early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:255–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, Boivin M. Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:471–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Sippola LK, Hoza B. Same and other: Interdependency between participation in same- and other-sex friendships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28(4):439–459. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Sippola LK, Newcomb AF. Variations in patterns of attraction of same- and other-sex peers during early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(2):147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capalidi DM, Patterson GR. Interrelated influences of contextual factors on antisocial behavior in childhood and adolescence for males. In: Fowles DC, Sutker P, Goodman SH, editors. Progress in experimental personality and psychopathology research. New York: Springer; 1994. pp. 165–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Lyman D, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Unraveling girls' delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Damon W, editor; Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 779–862. Series Ed. Vol. Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Terry R, Lenox KF, Lochman JE, Hyman C. Childhood peer rejection and aggression as predictors of stable patterns of adolescent disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1995a;7:697–713. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Terry R, Zakrisky A, Lochman J. Early adolescent social influence on delinquent behavior (SONOM) In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995b. pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Dishion TJ, Yasui M, Kavanagh K. An adaptive approach to family intervention: Linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(4):568–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Furman W, Konarski R. The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development. 2000;71(5):1395–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(2):337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Dowdy BB, Van Horn ML, Caldwell LL. Mixed-sex settings and the perception of competence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28(4):461–480. [Google Scholar]

- de Guzman MRT, Carlo G, Ontai LL, Koller SH, Knight GP. Gender and age differences in Brazilian children's friendship nominations and peer sociometric ratings. Sex Roles. 2004;51(3/4):217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Winter CE, Bullock BM. Adolescent friendship as a dynamic system: Entropy and deviance in the etiology and course of male antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(6):651–663. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047213.31812.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C. Other-sex friendship networks and the development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28(4):495–512. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. The world of coordinated play: Same- and cross-sex friendship in young children. In: Gottman JM, Parker JG, editors. Conversations of friends: Speculations on affective development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1986. pp. 139–191. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, Steffensmeier D, Bell KE. Gender and serious violence: Untangling the role of friendship sex composition and peer violence. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2007;5(3):235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Same- and cross-sex friends: Implications for interactions and social skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1988;3:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Loeber R, Green S. Conduct disorder in girls: A review of the literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:3–19. doi: 10.1023/a:1021811307364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw DS. Developmental and social influences on young girls' early problem behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:95–113. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs DM, Parker JG, Hoffman LW. Behavioral, affective, and social correlates of involvement in cross-sex friendship in elementary school. Child Development. 1996;67:2269–2286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Jordan KY, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Peer rejection in childhood, involvement with antisocial peers in early adolescence, and the development of externalizing behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(2):337–354. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Best friendships, group relationships, and antisocial behavior in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19(4):413–437. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019004001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45(4):513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CL, Fabes RA. The stability and consequences of young children's same-sex peer interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:431–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall P, Hymel S. Same-gender versus cross-gender friendship conceptions: Similar or different? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53(3):347–380. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Life-course-persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 570–598. [Google Scholar]

- Möller K, Stattin H. Are close relationships in adolescence linked with partner relationships in midlife? A longitudinal, prospective study. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25(1):69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Borge AI. The timing of middle-childhood peer rejection and friendship: Linking early behavior to early-adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 2007;78(4):1037–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehler TF, Dishion TJ. Interpersonal dynamics within adolescent friendships: Dyadic mutuality, deviant talk, and patterns of antisocial behavior. Child Development. 2007;78(5):1611–1624. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleydon AP, Schner JG. Female adolescent friendship and delinquent behavior. Adolescence. 2001;36(142):189–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder HM. The effect of gender role orientation and same- and cross-sex friendship formation. Sex Roles. 2003;49(3/4):143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(1):98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Berndt TJ. Friendship and peer relations. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Silverthorn P, Frick PJ. Developmental pathways to antisocial behavior: The delayed-onset pathway in girls. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:101–126. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippola LK. Getting to know the “other”: The characteristics and developmental significance of other-sex relationships in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28(4):407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Sippola LK, Bukowski WM, Noll RB. Age differences in children's and early adolescents' liking for same-sex and other-sex peers. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1997;43:547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Bennett C, Englund M, Urban J, Shulman S. The significance of gender boundaries in preadolescence: Contemporary correlates and antecedents of boundary violation and maintenance. Child Development. 1993;64:455–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Dishion TJ, Light J, Yasui M. Implementing family-centered interventions within the public middle school: Linking service delivery to change in student problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33(6):723–733. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lier PAC, Vitaro F, Wanner B, Vuijk P, Crijnen AAM. Gender differences in developmental links among antisocial behavior, friends' antisocial behavior, and peer rejection in childhood: Results from two cultures. Child Development. 2005;76(4):841–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Tremblay RE. Influence of deviant friends on delinquency: Searching for moderator variables. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(4):313–325. doi: 10.1023/a:1005188108461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbatany L, McDougall P, Hymel S. Gender-differentiated experience in the peer culture: Links to intimacy in preadolescence. Social Development. 2000;9(1):62–79. [Google Scholar]