Summary

A paired presentation of an odor and electric shock induces aversive odor memory in Drosophila melanogaster [1, 2]. Electric shock reinforcement is mediated by dopaminergic neurons [3–5], and it converges with the odor signal in the mushroom body (MB) [2, 6–8]. Dopamine is synthesized in ~280 neurons that form distinct cell clusters [9–11] and is involved in a variety of brain functions [9, 12–20]. Recently, one of the dopaminergic clusters (PPL1) that includes MB-projecting neurons was shown to signal reinforcement for aversive odor memory [21]. As each dopaminergic cluster contains multiple types of neurons with different projections and physiological characteristics [11, 20], functional understanding of the circuit for aversive memory requires cellular identification. We here show that MB-M3, a specific type of dopaminergic neurons in cluster PAM, is preferentially required for the formation of labile memory. Strikingly, flies formed significant aversive odor memory without electric shock, when MB-M3 was selectively stimulated together with odor presentation. We additionally identified another type of dopaminergic neurons in the PPL1 cluster, MB-MP1, which can induce aversive odor memory. As MB-M3 and MB-MP1 target the distinct subdomains of the MB, these reinforcement circuits might induce different forms of aversive memory in spatially segregated synapses in the MB.

Results and Discussion

Dopaminergic neurons that project to the mushroom body

To functionally manipulate restricted neurons for the induction of aversive odor memory, we searched for GAL4 expression drivers that label specific subsets of the MB-projecting dopaminergic neurons. A recent anatomical study using GAL4 drivers systematically described the neurons connecting the MB and other brain regions [22]. By immunolabeling of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) [23], an enzyme required for dopamine biosynthesis, we found at least five different types of MB-projecting dopaminergic neurons distributed to two clusters: MB-M3 and MB-MVP1 in the PAM cluster, and MB-V1, MB-MV1 and MB-MP1 in the PPL1 cluster (see Table S2 for the summary). Their terminals in the mushroom body (MB) are restricted in distinct subdomains. As different types of the major MB intrinsic neurons Kenyon cells have their own roles in dynamics of short- [24–26] and long-lasting [25, 27] odor memories, these dopaminergic neurons may signal different forms of reinforcement. In contrast, MB-M4, MB-V2, MB-V3, MB-V4, MB-CP1, MB-MV2, and MB-MVP2 were not labeled by the anti-TH antibody (data not shown). Based on the specificity of GAL4 drivers, we started our behavioral analysis with a specific type of dopaminergic neurons: MB-M3 (Figure 1A).

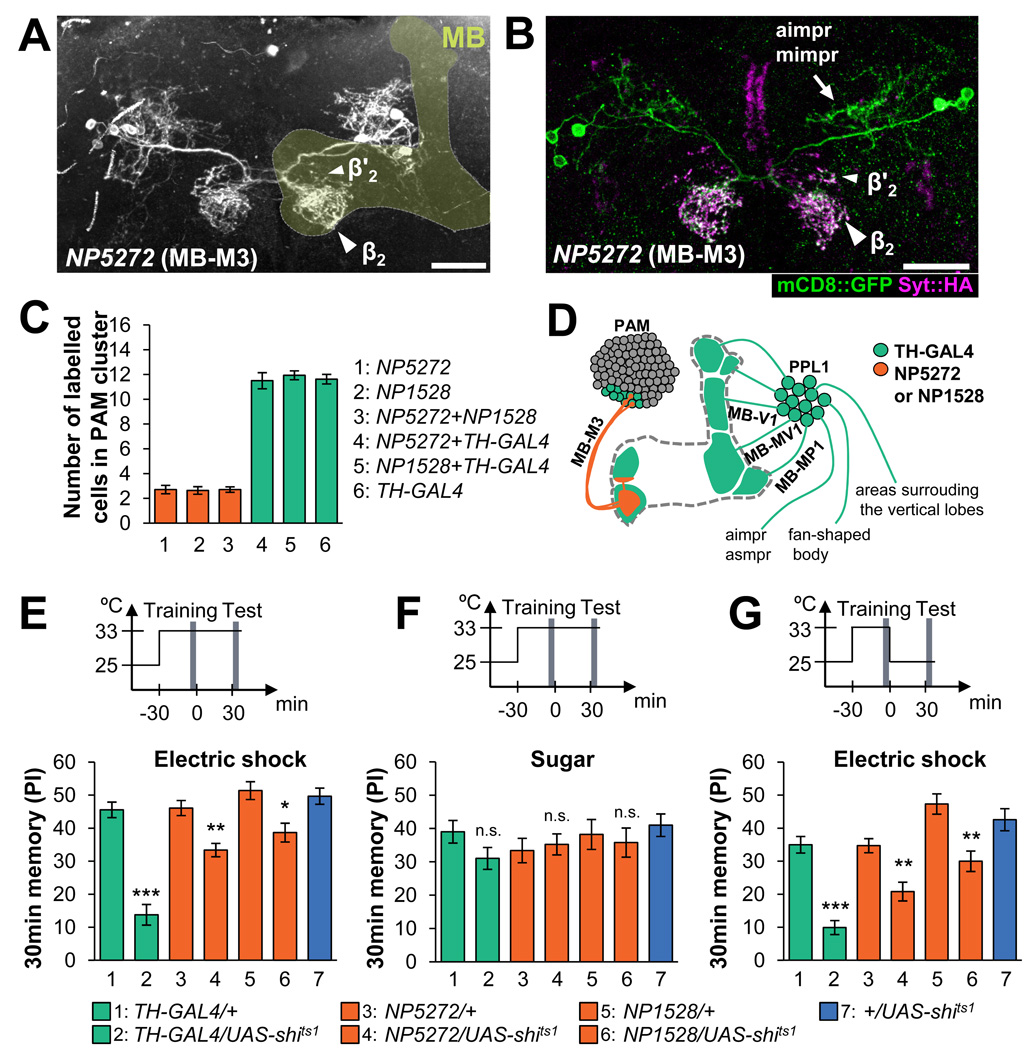

Figure 1. Dopaminergic inputs into the mushroom body via MB-M3 neurons.

(A) Projection of MB-M3 neurons visualized in NP5272 UAS-mCD8::GFP. In the MB (light green overlay based on the Synapsin counterstaining), MB-M3 neurons arbors in the medial tip of the β lobe (β2; arrowhead). Sparse terminals are detected also in the β' lobe ((β’2; small arrowhead).

(B) In UAS-Syt::HA; NP5272 UAS-mCD8::GFP, the arborizations in the anterior and middle inferiormedial protocerebrum (aimpr-mimpr; arrows) are only weakly labeled by presynaptic marker Syt::HA (magenta), if any, relative to mCD8::GFP (green), implying their dendritic nature. Scale bar 20 µm.

(C) The GAL4-expressing cells in the PAM cluster are visualized with UAS-Cameleon2.1. and counted. No significant difference is observed between NP5272, NP1528 and the comnbination of them. Also, combining NP5272 and NP1528 does not significantly increase the number of the labeled cells as compared to TH-GAL4 alone. Throughout the paper, bars and error bars represent the mean and s.e.m., respectively. Unless otherwise stated, the most conservative statistical result of multiple pair-wise comparisons is shown throughout the paper. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001; n.s. not significant.

(D) The diagram illustrates the terminal areas of GAL4-expressing cells of TH-GAL4 (green) and NP5272/NP1528 (orange) in the MB lobes, based on cell counting and a single-cell analysis [11]. The MB lobes are shown as an outline. See also Table S2.

(E) Aversive odor memory tested at 30 min after training. The respective dopaminergic neurons are blocked with Shits1 driven by TH-GAL4, NP5272 or NP1528. Block with these drivers significantly impairs aversive memory. n=17–22.

(F)Thirty-min appetitive memory of the same genotypes. Learning indices of all the experimental groups (TH-GAL4/UAS- shits1 and NP5272/UAS-shits1) are not significantly different from corresponding control groups (P>0.05; one-way ANOVA). n=13–16.

(G) Transient block only during aversive training. The results are essentially the same as in (E). n=20–22.

Two independent drivers, NP1528 and NP5272, selectively label three dopaminergic MB-M3 neurons per brain hemisphere on average (Figure 1A–D). They are labeled also in the TH-GAL4 driver (Figure 1C), which covers many more dopaminergic neurons (total ca. 130 cells in the brain) including at least six and two types of neurons projecting to the lobes and calyx of the MB, respectively (Figure 1D) [9, 11]. Presynaptic sites of MB-M3 are preferentially localized in the distal tips of the β lobe (βs2) and sparsely in the limited region of the distal β’ lobe (Figure 1B; see [22] for nomenclature), suggesting that they receive input from the anterior and middle inferior medial protocerebrum and give output in these subdomains of the MB lobes.

Requirement of MB-M3 output for shock-induced memory

To address the roles of the three MB-M3 neurons in aversive reinforcement of electric shock, we blocked output of these neurons by expressing Shits1, a dominant negative temperature sensitive variant of Dynamin that blocks synaptic vesicle endocytosis at high temperature [28]. Blocking not only many types of dopaminergic neurons but also MB-M3 neurons alone impaired aversive memory tested at 30 min after conditioning (Figure 1E). Notably, the effect of blocking MB-M3 on aversive odor memory was significant, but less pronounced than that with TH-GAL4. Consistent with the previous report [3], blocking MB-M3 and other dopaminergic neurons did not significantly affect reflexive avoidance of the electric shock (Table S1). We then contrasted aversive and appetitive memory with the same odorants, because the requirement of the reinforcement circuit should be selective. As expected, appetitive odor memory reinforced by sugar was not disturbed (Figure 1F), suggesting that odor discrimination and locomotion of these flies that are required for the task should not be affected significantly under the blockade of GAL4-expressing cells.

We next asked whether the output of the MB-M3 neurons is required specifically during memory formation by blocking them only transiently during training. We found significant impairment of 30 min-memory by the transient block of MB-M3 (Figure 1G). By contrast, the block after the training period (i.e. during the retention interval and the test period) and the experiment at continuous permissive temperature did not significantly impair odor memory (Figure S1). These results together indicate that the phenotype is attributed to the impairment of memory formation rather than the memory retention, retrieval, or the effect of the genetic background.

Aversive reinforcement for a distinct memory component

Given the partial requirement of MB-M3 for 30 min memory (Figure 1E and 1G), we hypothesized that the output of MB-M3 may be responsible for a specific memory component. We blocked MB-M3 or neurons labeled in TH-GAL4 during training and examined memory retention up to 9 hours. Blocking with TH-GAL4 significantly impaired aversive odor memory at all time points (Figure 2A). Intriguingly, the effect of the MB-M3 block was most pronounced in the middle-term memory (2 h after training); memory tested immediately and 9 h after training was only slightly impaired, if any. The dynamics of memory decay was different from the block with TH-GAL4 and control groups (Figure 2A). This result is consistent with the previous report showing that immediate memory is not affected by blocking many of PAM cluster neurons [21].

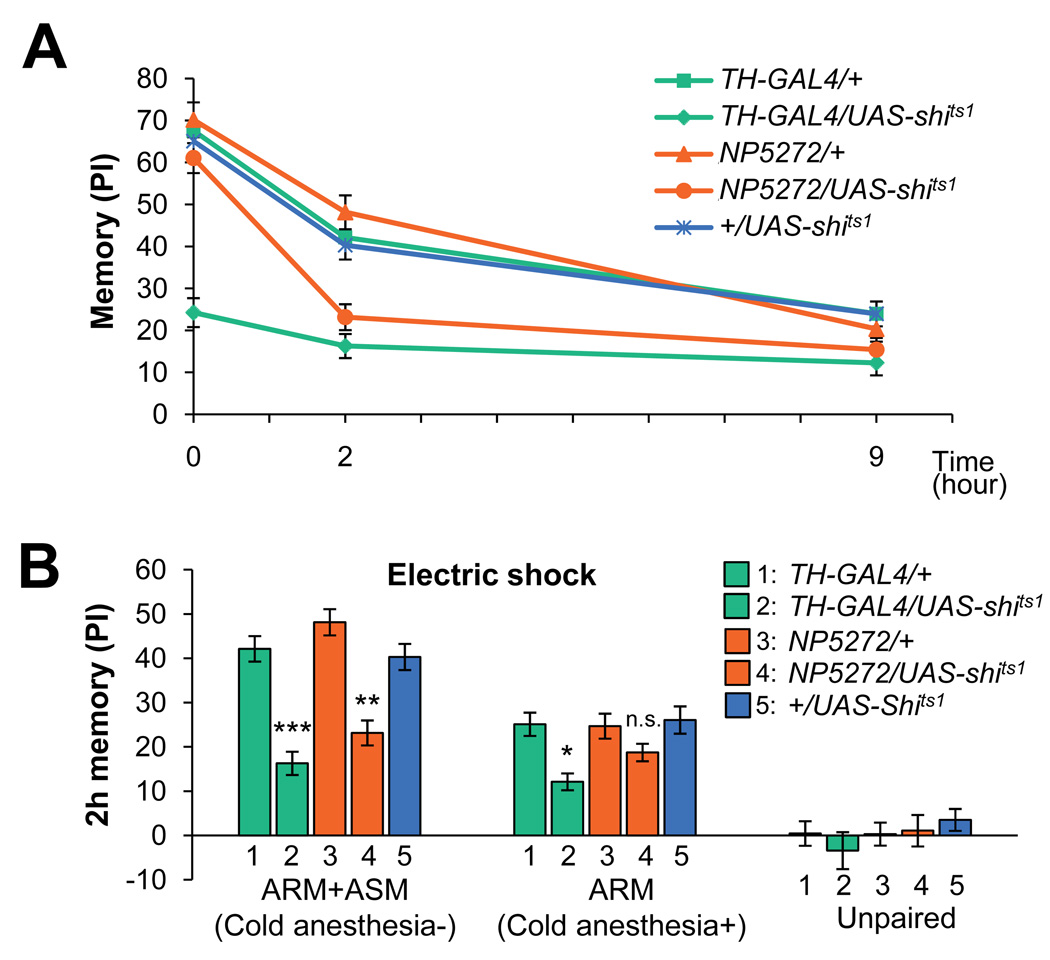

Figure 2. Preferential requirement of MB-M3 for inducing labile middle-term memory.

(A) Requirement of the MB-M3 neurons for different memory phases. Flies were trained and tested immediately at restrictive temperature, or kept for two or nine hours and tested at permissive temperature. Memory is significantly impaired at all three retention intervals by TH-GAL4. Blocking MB-M3 slightly affects immediate and 9-hour memory, but only 2-hour memory is significantly impaired. n=14–20.

(B) Total memory (ASM+ARM; the same data set as in a), a consolidated memory component (ARM), and memory induced by unpaired presentation of odors and electric shock tested at 2 hours after training (n=12–18). Although the block with TH-GAL4 impairs both total memory and ARM, only total memory is significantly impaired when MB-M3 neurons are blocked during training. The requirement of the MB-M3 neurons for the total memory and ARM is differential (P<0.05; significant interaction [genotype X cold shock treatment] in two-way ANOVA).

What type of memory is impaired by blocking the MB-M3? Initially labile odor memory in Drosophila is consolidated gradually and becomes resistant to retrograde amnesia [29, 30]. At two hours after training, labile anesthesia-sensitive memory (ASM) and consolidated anesthesia-resistant memory (ARM) coexist [29, 30]. ARM can be measured by erasing ASM with short cold anesthesia of flies. Manipulation of various signaling molecules, such as Amnesiac, AKAP, DC0, Rac or NMDAR [1, 31–35] (but see [36] for the role of DC0 for ARM), affects ASM and causes memory dynamics similar to that caused by the MB-M3 block (Figure 2A).

To address whether the MB-M3 neurons are required selectively for ASM, we trained flies with their MB-M3 neurons blocked and, two hours later, measured their total memory and ARM. The output of MB-M3 during training was required for the total 2 h memory, whereas ARM was not significantly affected (Figure 2B). This suggests that the MB-M3 neurons preferentially contribute to the formation of ASM. In contrast, the block with TH-GAL4 significantly impaired both total memory and ARM (Figure 2B). Although the scores of ARM were small, subtle differences in ARM were detectable, because unpaired conditioning resulted in the significantly lower memory in every genotype (Figure 2B). Taken together, these results imply that multiple types of reinforcement neurons are recruited for the formation of different forms of memory.

Aversive odor memory formed by the activation of MB-M3

We next examined whether selective stimulation of the MB-M3 neurons can induce aversive odor memory without electric shock. Drosophila heat-activated cation channel dTRPA1 (also known as dANKTM1), allows transient depolarization of targeted neurons by raising temperature [37, 38]. To selectively activate the corresponding dopaminergic neurons, flies that express dTrpA1 by the above-described GAL4 drivers were trained with odor presentation and a concomitant temperature shift instead of electric shock (Figure 3A). To minimize the noxious effect of heat itself, we used moderate temperature (30°C) for activation. When examined immediately (approximately 2 min) after training, robust aversive memory was formed by the activation with TH-GAL4 (Figure 3B). Strikingly, selective activation of MB-M3 also caused significant aversive odor memory (Figure 3B). Unpaired presentation of an odor and dTRPA1-dependent activation did not cause significant associative memory (Figure 3C), indicating the importance of stimulus contingency.

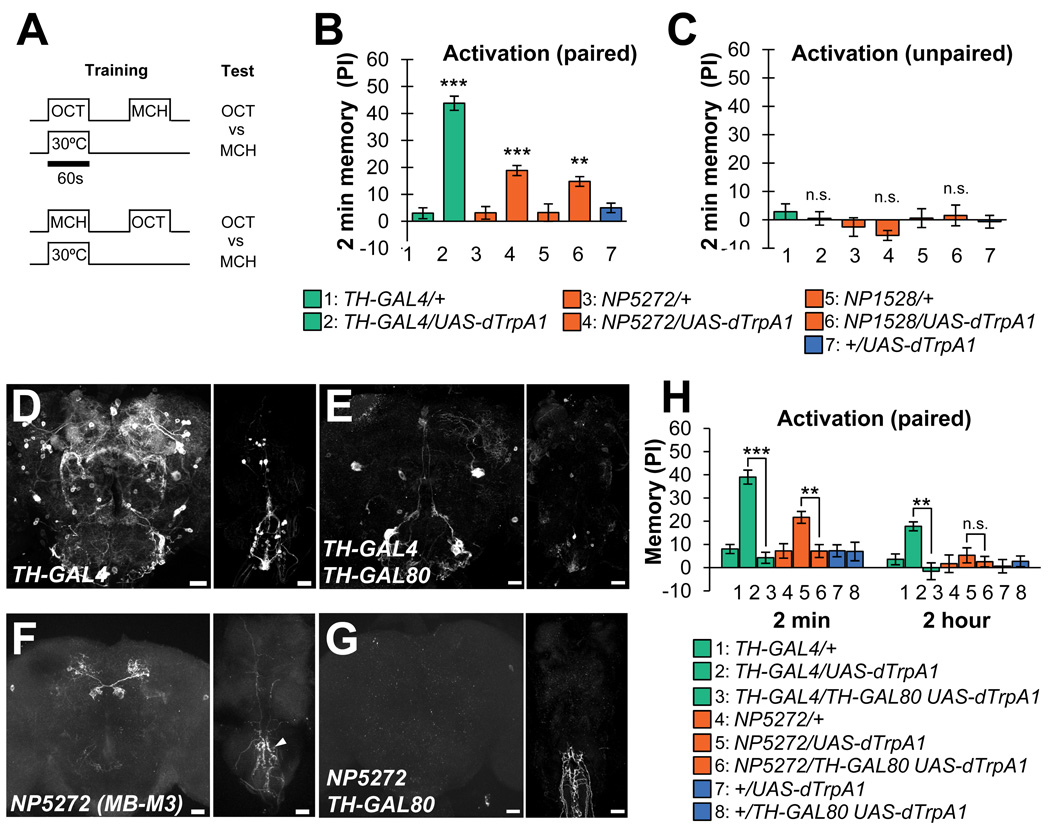

Figure 3. dTrpA1-dependent activation of MB-M3 can induce aversive odor memory.

(A) The conditioning protocol for dTrpA1-induced memory (see Experimental Procedures for detail).

(B) Immediate aversive odor memory formed by odor presentation and simultaneous thermo-activation of the subsets of dopaminergic neurons expressing dTrpA1. n=18–22.

(C) Thermo-activation did not induce aversive odor memory when it is applied 60–120 seconds prior to the presentation of the odor. n=10–12.

(D–G) Expression pattern of TH-GAL4 (D) and NP5272 (F) in the brain (left panels; frontal view, dorsal up) and thoracicoabdominal ganglion (right panels; dorsal view, anterior up). TH-GAL80 silences mCD8::GFP expression in MB-M3 (G) and the most of cells labeled by TH-GAL4 (E). Remaining cells are presumably non-dopaminergic cells judging from their size and position [11]. Scale bars: 20 µm.

(H) Immediate aversive odor memory induced by dTrpA1-dependent activation is significantly suppressed by TH-GAL80, indicating that the corresponding dopaminergic neurons are responsible. n=15–17.

Although the drivers for MB-M3 have a selective expression pattern, NP5272 has additional faint labeling of nerves in the abdominal ganglion and, only occasionally, other neurons in the brain (Figures 3F and S2A). To confirm that the activation of MB-M3 neurons was the cause of dTRPA1-induced odor memory, we expressed a GAL4 inhibitor, GAL80, in dopaminergic neurons using TH-GAL80 [39]. Indeed, TH-GAL80 suppressed reporter expression in dopaminergic neurons in NP5272 and TH-GAL4 (Figure 3D–G) and dTRPA1-induced odor memory to the control level (Figure 3H). These data suggest that selective activation of MB-M3 can induce immediate aversive memory, while blocking MB-M3 had a limited effect on immediate shock-induced memory (Figure 2A). This may suggest that the contribution of MB-M3 is redundant with other dopaminergic neurons in shock-induced immediate memory. Alternatively, the activation of MB-M3 by dTrpA1 might not fully recapitulate that in electric shock conditioning in terms of a temporal pattern and intensity.

We also measured dTRPA1-induced memory at 2 hours after training. With TH-GAL4 aversive memory was still significant, whereas the memory induced with MB-M3 activation diminished by 2 hours, indicating the labile nature of the memory (Figure 3H). Given the selective requirement of MB-M3 (Figure 2A), the contribution of MB-M3 to 2-hour memory might be interdependent with other dopaminerigic neurons. A similar interaction has been shown at the level of different subsets of Kenyon cells [24, 27, 34, 40, 41] and might thus be a potential consequence of the synergistic action of dopaminergic neurons.

Other individual dopaminergic neurons for aversive reinforcement

To explore the function of other types of MB-projecting dopaminergic neurons for aversive memory formation, we individually stimulated 4 different cell types (MB-MP1, MB-V1, MB-MVP1 and unnamed type that project to the β’ lobe) using selective GAL4 driver lines (NP2758, c061; MB-GAL80, MZ840 and NP6510; Figures 4 and S2; see Table S2 for the summary of labeled neurons).

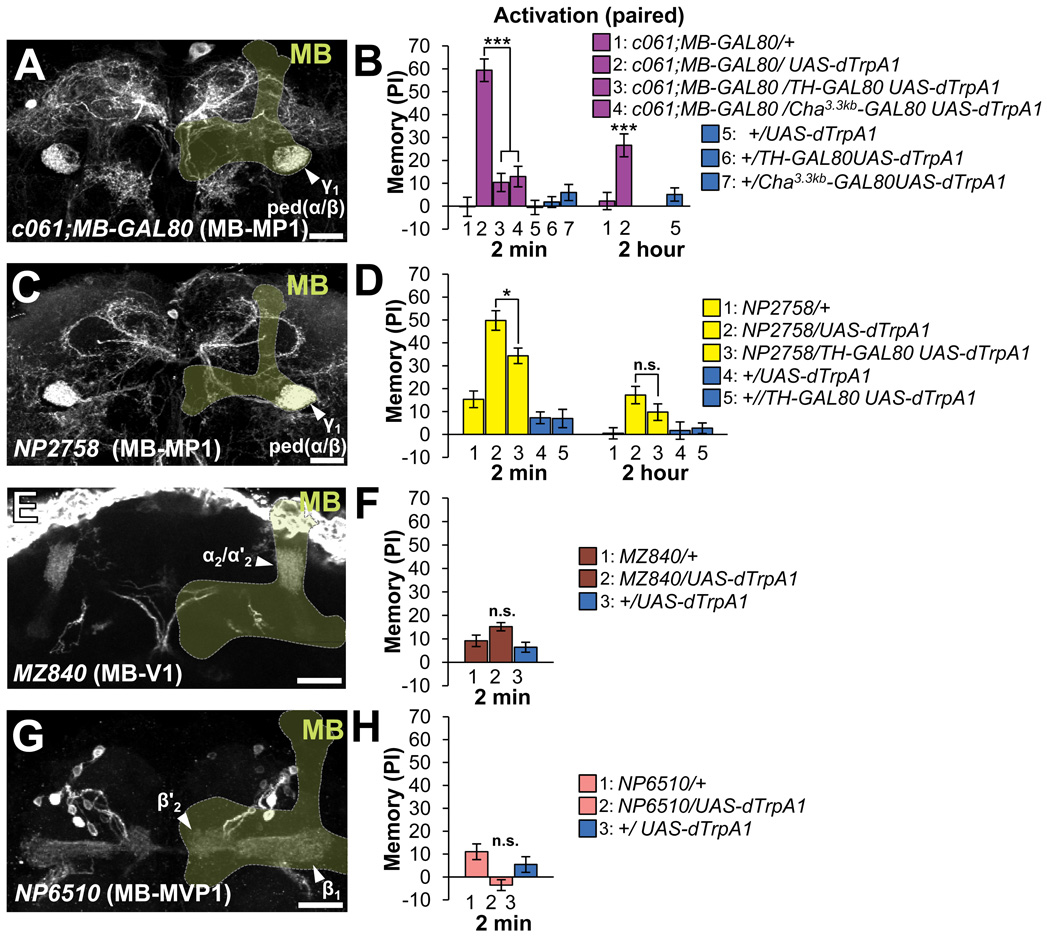

Figure 4. dTrpA1-induced memory by other dopaminergic neurons.

(A, C, E, G) Projection of brain regions including the MB (light green outline; frontal view, dorsal up). Various dopaminergic neurons projecting to the MB are visualized with mCD8::GFP (arrowheads) driven by c061; MB-GAL80 (A), NP2758 (C), MZ840 (E), and NP6510 (G). Scale bar 20 µm. see also Figure S2 and Table S2.

(B, D, F, H) Memory induced by dTrpA1-dependent activation of the various types of dopaminergic neurons.

(E) With c061;MB-GAL80, robust immediate and 2-hour memory are formed and significantly suppressed by TH-GAL80 and Cha3.3kb-GAL80. n=18–22.

(F) Activation of dTrpA1-expressing cells in NP2758 induces robust aversive odor memory, which is significantly suppressed by TH-GAL80. (G) Despite the tendency, no significant memory is formed with MZ840.

(H) With NP6510, the learning index of NP6510/UAS-dTrpA1 is different from NP6510/+ but not from +/UAS-dTrpA1. n=15–18.

c061; MB-GAL80 labels three dopaminergic neurons in the PPL1 cluster, including one MB-MP1 neuron that is labeled also in NP2758 (Figures 4A, 4C, S2B, S2E and Table S2) [20]. Activation with c061; MB-GAL80 induced robust immediate memory (Figures 4B). Furthermore, we found that Cha3.3kb-GAL80 strongly silenced reporter expression in two of three neurons in c061; MB-GAL80 and the effect on aversive memory to the control level (Figure S2B–C, 4B) [42]. As one remaining dopaminergic neuron projects to the anterior inferior medial protocerebrum, but not to the MB (Figure S2C)[11], MB-MP1 is more likely to be responsible for the formation of aversive memory. This suppression of transgene expression in dopaminergic neurons might be due to the incomplete recapitulation of Cha3.3kb enhancer (Figure S2B–C).The addition of TH-GAL80 also suppressed the effect of c061; MB-GAL80 to the control level (Figure 4B). Consistently, significant memory was induced with NP2758 (Figure 4C–D), although the suppression by TH-GAL80 was partial (Figure 4D), presumably through expression in non-dopaminergic neurons in NP2758 or incomplete suppression of dTRPA1 expression (Figure S2E–F). The formed memory with c061; MB-GAL80 decayed significantly but lasted for 2 hours (Figure 4B). Taken together, these results revealed that the specific cell type within the PPL1 cluster, MB-MP1, can mediate aversive reinforcement. Intriguingly, the recent work using the same driver reported that MB-MP1 has another important role for suppressing the retrieval of appetitive memory depending on the feeding states [20]. As the output of MB-MP1 is dispensable for 3-hour memory induced by electric shock [20], MB-MP1 might mainly induce short-lasting odor memory. Alternatively, MB-MP1 neurons might be recruited to mediate aversive reinforcement other than electric shock.

MZ840 and NP6510 that label the single PPL1 neuron (MB-V1) and 15 PAM neurons (MB-MVP1 and unnamed cell type), respectively (Fig. 4E, G, S2G–J). Thermo-activation with these drivers did not cause significant memory (Figures 4E–H and S2G–J). This may indicate PAM and PPL1 cluster contain functionally heterogeneous population in terms of aversive reinforcement signals. Consistently, each type of PPL1 neurons differentially responds to odors and electric shock [11]. It is noteworthy that MB-MVP1 synapse onto the restricted subdomains adjacent to the terminals of MB-M3. Thus, the activation of specific sets of dopaminergic neurons rather than the total amount of dopamine input in the MB may be critical for memory formation. Despite the particular importance of the dopamine signal in the vertical lobes of the MB [11, 43, 44], we could not examine them, except for MB-V1, due to the lack of reasonably specific GAL4 drivers.

Parallel reinforcement input to the mushroom body

In a current circuit model of aversive odor memory, associative plasticity is generated in the output site of the MB (i.e. the presynaptic terminals of Kenyon cells) upon internal convergence of neuronal signals of odor and electric shock [2, 6, 7]. Type I adenylyl cyclase, Rutabaga, is an underlying molecular coincidence detector to form a memory trace [6, 40, 44, 45]. Rutabaga in different types of Kenyon cells (e.g. γ and α/β neurons) together acts to form complete aversive memory [24, 27, 40]. Thus, local, but spatially segregated, Rutabaga stimulation through multiple dopaminergic pathways may induce distinct memory traces [11, 44–46].

We showed the selective requirement of MB-M3 for middle-term ASM, whereas blocking many more dopaminergic neurons impaired all memory phases examined in this study (Figure 2). Therefore, electric shock recruits a set of distinct dopaminergic neurons that forms a parallel reinforcement circuit in the subdomains of the MB. Compartmentalized synaptic organization along the trajectory of Kenyon cell axons may well explain how the MB as a single brain structure can support "pleiotropic" behavioral functions [12, 25, 46].

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly strains

All flies were raised on standard medium. For behavioral assay, F1 progenies of the crosses between females of UAS-shits1 (X, III)[28], UAS-dTrpA1(II) [37], UAS-dTrpA1 TH-GAL80 (II) [39], UAS-dTrpA1; Cha3.3kb-GAL80 (II, III) [42] or white and males of NP5272 (II) [22], NP1528 (II) / CyO [22], NP2758 (X) [22], NP6510 (III) [22], MZ840 (III) or TH-GAL4 (III) [9] were employed. For the experiments with c061;MB-GAL80 (X and III),female of this strain was used for crosses. After measurement, flies without a GAL4 driver (i.e. those with the balancer or male of NP2758 crosses) were excluded from calculation. Accordingly, for experiments with NP2758 (Figure 4D), only the learning indices of females were compared. For experiments with UAS-shits1 and UAS-dTrpA1, flies were raised at 18°C and 25°C, 60% relative humidity and used during 8–14 and 7–12 days after eclosion, respectively to allow sufficient accumulation of effecter genes without age-related memory impairment. For anatomical assay, F1 progenies of the crosses between females of UAS-mCD8::GFP(X, II, III) [47], UAS-Syt::HA(X); UAS-mCD8:GFP(II) [48], UAS-mCD8::GFP(X); UAS-mCD8:: GFP(III), UAS-mCD8::GFP(X); TH-GAL80(II); UAS-mCD8::GFP(III), UAS-Cameleon2.1, or NP5272 UAS-Cameleon2.1 (II) and males of MZ604, MZ840, NP242 (III) NP2150(X), NP2297 (II), NP2492 (X), NP2583 (II), NP3212 (III), NP7251 (X) [22], or lines used for behavioral assays were employed. The progeny of these crosses were all heterozygous for transgenes and homozygous for white in hybrid genetic backgrounds of original strains.

Behavioral assays

Standard protocol for olfactory conditioning with two odors (4-methylcyclohexanol and 3-octanol) was used. Flies were trained by receiving one odor (CS+) for 1 min with 12 pulses of electric shocks (90V DC) or, for appetitive learning, dried filter paper having absorbed with 2 M sucrose solution [1, 3, 49]. Subsequently, they received another odor (CS−) for 1 min, but without electroshock or sugar. After a given retention time, the conditioned response of the trained flies was measured with a choice between CS+ and CS− for 2 min in a T-maze. No or a few percentage of flies was trapped in the middle compartment and did not choose either odor. A learning index (LI) was then calculated by taking the mean preference of two groups, which had been trained reciprocally in terms of the two odors used as CS+ and CS− [1]. To cancel the effect of the order of reinforcement [1, 50], the first odor was paired with reinforcement in a half of experiments and the second odor was paired with reinforcement in another half.

For rigorous comparison of aversive and appetitive memory (Figures 1E–F), flies were starved for 40–68 hours at 18°C (calibrated with 5–10% of the mortality rate) and treated equally with only a difference being the type of reinforcement (sugar or electric shock). Unlike previous reports, flies for appetitive memory were trained only once for one minute instead of twice.

To measure ARM, trained flies were anesthetized by transferring them into pre-cooled tubes (on ice) for 60 seconds at 100 min after training (Figure 2B; Quinn and Dudai, 1976). For conditioning with thermo-activation by dTRPA1 (Figures 3B–C, 3H, 4B, 4D, 4F and 4H), we trained flies in the same way as electric shock conditioning except that flies were transferred to the pre-warmed T-maze in the climate box (30–31°C) only during the presentation of one of the two odorants (60 seconds). To minimize the noxious effect of heat itself, we used moderate temperature (30–31°C) for activation. This temperature shift by itself only occasionally induced small aversive odor memory that is significantly higher than the chance level (see the control groups in Figures 3 and 4). MZ604/UAS-dTrpA1 was not tested for olfactory learning because of obvious motor dysfunction at high temperature.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software). Because all groups tested did not violate the assumption of the normal distribution and the homogeneity of variance, mean performance indices were compared with one-way ANOVA followed by planned multiple pair-wise comparisons (Bonferroni correction). Bars and error bars represent the mean and s.e.m., respectively. Asterisk denotes; * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001; n.s. not significant. When comparisons with multiple control groups give distinct significance levels, only the most conservative result is shown in the graph.

Immunohistochemistry

Female F1 progenies (5–10 days after eclosion at 25°C) from the crosses described above were examined. The brain and thoracicoabdominal ganglion were prepared for immunolabeling and analyzed as previously described [49, 51]. The brains were dissected in Ringer's solution, fixed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% formaldehyde and 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBT; Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature, and subsequently rinsed with PBT three times (3× 10min). After being blocked with PBT containing 3% normal goat serum (Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature, the brains were incubated with the primary antibodies in PBT at 4°C overnight. The employed primary antibodies were the rabbit polyclonal antibody to GFP (1:1000; Molecular Probes), GFP (1:1000; Sigma), presynaptic protein Synapsin (1:20; 3C11) [52], HA (1:200; 16B12; Covance; MMS-101P).The brains were washed with PBT for 20min three times and incubated with secondary antibodies in the blocking solution at 4°C overnight. The employed secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:1000 or 1:500; Molecular Probes) or anti-mouse IgG (1000; Molecular Probes) and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:250; Jackson ImmunoResearch) or anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Molecular Probes). Finally, the brains were rinsed with PBT (3× 20 min + 1× 1h) and mounted in Vectashield (Vector), and frontal optical sections of whole-mount brains were taken with a confocal microscopy, Olympus FV1000, Leica SP1 or SP2. For the quantitative analysis, brains were scanned with comparable intensity and offset. Images of the confocal stacks were analyzed with the open-source software Image-J (NIH).

Research highlights

Thermo-genetic stimulation/suppression of specific sets of dopaminergic neurons

MB-M3 is preferentially required for labile olfactory memory

Local stimulation in the mushroom body is sufficient for aversive memory formation

Multiple types of dopaminergic neurons mediate aversive reinforcement

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. B. Friedrich, K. Grübel, A. Gruschka and B. Mühlbauer for excellent technical assistance; W. Neckameyer for anti-TH antibody; P. A. Garrity, S. Waddel, J. D. Armstrong, NP consortium/Kyoto Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, and Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks. We are also grateful to M. Heisenberg, M. Hübener, I. Kadow, T. Suzuki, N. K. Tanaka, and A. Yarali, for discussion and/or critical reading of the manuscript. Y.A. received doctoral fellowship from Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K.I.), the National Institute of Health (to T.K.), Emmy-Noether Program from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to H.T.) and Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (to H.T.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tully T, Quinn WG. Classical conditioning and retention in normal and mutant Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Physiol [A] 1985;157:263–277. doi: 10.1007/BF01350033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGuire SE, Deshazer M, Davis RL. Thirty years of olfactory learning and memory research in Drosophila melanogaster. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:328–347. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwaerzel M, Monastirioti M, Scholz H, Friggi-Grelin F, Birman S, Heisenberg M. Dopamine and octopamine differentiate between aversive and appetitive olfactory memories in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10495–10502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10495.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroll C, Riemensperger T, Bucher D, Ehmer J, Völler T, Erbguth K, Gerber B, Hendel T, Nagel G, Buchner E, et al. Light-induced activation of distinct modulatory neurons triggers appetitive or aversive learning in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1741–1747. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vergoz V, Roussel E, Sandoz JC, Giurfa M. Aversive learning in honeybees revealed by the olfactory conditioning of the sting extension reflex. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber B, Tanimoto H, Heisenberg M. An engram found? Evaluating the evidence from fruit flies. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heisenberg M. Mushroom body memoir: from maps to models. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:266–275. doi: 10.1038/nrn1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keene AC, Waddell S. Drosophila olfactory memory: single genes to complex neural circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrn2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friggi-Grelin F, Coulom H, Meller M, Gomez D, Hirsh J, Birman S. Targeted gene expression in Drosophila dopaminergic cells using regulatory sequences from tyrosine hydroxylase. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:618–627. doi: 10.1002/neu.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nässel DR, Elekes K. Aminergic neurons in the brain of blowflies and Drosophila: dopamine- and tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons and their relationship with putative histaminergic neurons. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;267:147–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00318701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao Z, Davis RL. Eight different types of dopaminergic neurons innervate the Drosophila mushroom body neuropil: anatomical and physiological heterogeneity. Front Neural Circuits. 2009;3:5. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.005.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riemensperger T, Völler T, Stock P, Buchner E, Fiala A. Punishment prediction by dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1953–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang K, Guo JZ, Peng Y, Xi W, Guo A. Dopamine-mushroom body circuit regulates saliency-based decision-making in Drosophila. Science. 2007;316:1901–1904. doi: 10.1126/science.1137357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seugnet L, Suzuki Y, Vine L, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. D1 receptor activation in the mushroom bodies rescues sleep-loss-induced learning impairments in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1110–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Yin Y, Lu H, Guo A. Increased dopaminergic signaling impairs aversive olfactory memory retention in Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andretic R, Kim YC, Jones FS, Han KA, Greenspan RJ. Drosophila D1 dopamine receptor mediates caffeine-induced arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20392–20397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806776105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selcho M, Pauls D, Han KA, Stocker RF, Thum AS. The role of dopamine in Drosophila larval classical olfactory conditioning. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lebestky T, Chang JS, Dankert H, Zelnik L, Kim YC, Han KA, Wolf FW, Perona P, Anderson DJ. Two different forms of arousal in drosophila are oppositely regulated by the dopamine D1 receptor ortholog DopR via distinct neural circuits. Neuron. 2009;64:522–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu T, Dartevelle L, Yuan C, Wei H, Wang Y, Ferveur JF, Guo A. Reduction of dopamine level enhances the attractiveness of male Drosophila to other males. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krashes MJ, DasGupta S, Vreede A, White B, Armstrong JD, Waddell S. A neural circuit mechanism integrating motivational state with memory expression in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;139:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claridge-Chang A, Roorda RD, Vrontou E, Sjulson L, Li H, Hirsh J, Miesenböck G. Writing memories with light-addressable reinforcement circuitry. Cell. 2009;139:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka NK, Tanimoto H, Ito K. Neuronal assemblies of the Drosophila mushroom body. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:711–755. doi: 10.1002/cne.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neckameyer WS, Woodrome S, Holt B, Mayer A. Dopamine and senescence in Drosophila melanogaster. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akalal DB, Wilson CF, Zong L, Tanaka NK, Ito K, Davis RL. Roles for Drosophila mushroom body neurons in olfactory learning and memory. Learn Mem. 2006;13:659–668. doi: 10.1101/lm.221206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isabel G, Pascual A, Preat T. Exclusive consolidated memory phases in Drosophila. Science. 2004;304:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.1094932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zars T. Behavioral functions of the insect mushroom bodies. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:790–795. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blum AL, Li W, Cressy M, Dubnau J. Short- and long-term memory in Drosophila require cAMP signaling in distinct neuron types. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1341–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamoto T. Conditional modification of behavior in Drosophila by targeted expression of a temperature-sensitive shibire allele in defined neurons. J Neurobiol. 2001;47:81–92. doi: 10.1002/neu.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folkers E, Drain P, Quinn WG. Radish, a Drosophila mutant deficient in consolidated memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8123–8127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinn WG, Dudai Y. Memory phases in Drosophila. Nature. 1976;262:576–577. doi: 10.1038/262576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubnau J, Tully T. Gene discovery in Drosophila: new insights for learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:407–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwaerzel M, Jaeckel A, Mueller U. Signaling at A-kinase anchoring proteins organizes anesthesia-sensitive memory in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1229–1233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4622-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu CL, Xia S, Fu TF, Wang H, Chen YH, Leong D, Chiang AS, Tully T. Specific requirement of NMDA receptors for long-term memory consolidation in Drosophila ellipsoid body. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1578–1586. doi: 10.1038/nn2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuai Y, Lu B, Hu Y, Wang L, Sun K, Zhong Y. Forgetting is regulated through Rac activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2010;140:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, Tully T, Kalderon D. Effects of a conditional Drosophila PKA mutant on olfactory learning and memory. Learn Mem. 1996;2:320–333. doi: 10.1101/lm.2.6.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horiuchi J, Yamazaki D, Naganos S, Aigaki T, Saitoe M. Protein kinase A inhibits a consolidated form of memory in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20976–20981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810119105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamada FN, Rosenzweig M, Kang K, Pulver SR, Ghezzi A, Jegla TJ, Garrity PA. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454:217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viswanath V, Story GM, Peier AM, Petrus MJ, Lee VM, Hwang SW, Patapoutian A, Jegla T. Opposite thermosensor in fruitfly and mouse. Nature. 2003;423:822–823. doi: 10.1038/423822a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sitaraman D, Zars M, Laferriere H, Chen YC, Sable-Smith A, Kitamoto T, Rottinghaus GE, Zars T. Serotonin is necessary for place memory in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5579–5584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zars T, Fischer M, Schulz R, Heisenberg M. Localization of a short-term memory in Drosophila. Science. 2000;288:672–675. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krashes MJ, Keene AC, Leung B, Armstrong JD, Waddell S. Sequential use of mushroom body neuron subsets during drosophila odor memory processing. Neuron. 2007;53:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitamoto T. Conditional disruption of synaptic transmission induces male-male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13232–13237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202489099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomchik SM, Davis RL. Dynamics of learning-related cAMP signaling and stimulus integration in the Drosophila olfactory pathway. 2009;64:510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gervasi N, Tchenio P, Préat T. PKA dynamics in a Drosophila learning center: coincidence detection by rutabaga adenylyl cyclase and spatial regulation by dunce phosphodiesterase. Neuron. 2010;65:516–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomchik SM, Davis RL. Dynamics of learning-related cAMP signaling and stimulus integration in the Drosophila olfactory pathway. Neuron. 2009;64:510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu D, Akalal DB, Davis RL. Drosophila alpha/beta mushroom body neurons form a branch-specific, long-term cellular memory trace after spaced olfactory conditioning. Neuron. 2006;52:845–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson IM, Ranjan R, Schwarz TL. Synaptotagmins I and IV promote transmitter release independently of Ca(2+) binding in the C(2)A domain. Nature. 2002;418:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature00915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thum AS, Jenett A, Ito K, Heisenberg M, Tanimoto H. Multiple memory traces for olfactory reward learning in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11132–11138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2712-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim YC, Lee HG, Han KA. D1 dopamine receptor dDA1 is required in the mushroom body neurons for aversive and appetitive learning in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7640–7647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1167-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aso Y, Grubel K, Busch S, Friedrich AB, Siwanowicz I, Tanimoto H. The mushroom body of adult Drosophila characterized by GAL4 drivers. J Neurogenet. 2009;23:156–172. doi: 10.1080/01677060802471718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klagges BR, Heimbeck G, Godenschwege TA, Hofbauer A, Pflugfelder GO, Reifegerste R, Reisch D, Schaupp M, Buchner S, Buchner E. Invertebrate synapsins: a single gene codes for several isoforms in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3154–3165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03154.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.