Abstract

Background

Nine DSM-IV-TR criterion symptom domains are evaluated to diagnose major depressive disorder (MDD). The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) provides an efficient assessment of these domains and is available as a clinician rating (QIDS-C16), a self-report (QIDS-SR16), and in an automated, interactive voice response (IVR) (QIDS-IVR16) telephone system. This report compares the performance of these three versions of the QIDS and the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17).

Methods

Data were acquired at baseline and exit from the first treatment step (citalopram) in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial. Outpatients with nonpsychotic MDD who completed all four ratings within ±2 days were identified from the first 1500 STAR*D subjects. Both item response theory and classical test theory analyses were conducted.

Results

The three methods for obtaining QIDS data produced consistent findings regarding relationships between the nine symptom domains and overall depression, demonstrating interchangeability among the three methods. The HRSD17, while generally satisfactory, rarely utilized the full range of item scores, and evidence suggested multidimensional measurement properties.

Conclusions

In nonpsychotic MDD outpatients without overt cognitive impairment, clinician assessment of depression severity using either the QIDS-C16 or HRSD17 may be successfully replaced by either the self-report or IVR version of the QIDS.

Keywords: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, item response theory, Samejima graded response model, depressive symptoms

Accurate, time-efficient measurement of depressive symptom severity is of great importance in conducting cost-efficient, clinical trials. Development of a self-report measure that accurately reflects overall symptom severity would be useful to both clinicians and researchers who wish to monitor treatment outcomes. In addition, if automated methods for obtaining such ratings over the telephone using interactive voice response (IVR) technology were available, researchers and clinicians would be able to obtain such measures at virtually any time or place.

The growing importance of symptom remission in managing depression has been recognized for several years (American Psychiatric Association 2000b; Bauer et al 2002a, 2002b; Canadian Psychiatric Association Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments 2001; Crismon et al, 1999; Depression Guideline Panel, 1993; Reesal et al, 2001; Rush and Ryan, 2002). The field has yet to agree on and validate the best definition of remission. The ascertainment of remission or partial remission, however, based on DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000a, page 412), logically recommends that all nine diagnostic criterion symptoms that define the syndrome be assessed. Some would also recommend, however, that an assessment of anxiety, other common symptoms (e.g., irritability, pain), and even day-to-day function could also be important to fully define remission.

The most commonly used clinician ratings of depressive symptom severity, e.g., the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HRSD) (Hamilton. 1960, 1967) and the Montgomery-Äsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and Äsberg, 1979), do not specifically identify and weigh equally each of the diagnostic criterion symptoms specified by DSM-IV-TR. It could be argued that more common criterion symptoms (e.g., sad mood) should contribute to a greater degree to total severity than less common symptoms (e.g., suicidal thinking). The DSM-IV-TR, at least, does not differentially weight the symptoms to define a major depressive episode or to establish the presence of partial remission or remission. Self-report versions of the HRSD (Carroll et al, 1981; Smouse et al, 1981; Reynolds and Kobak, 1995) and of the MADRS (Svanborg and Äsberg 2001) are available. However, the limitations inherent in the original clinician ratings likely apply to these self-reports (e.g., confounded items, missing criterion diagnostic items, etc.) (Rush et al, 1996).

The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) was developed initially as a 28-item clinician rating scale and a matched 28-item self-report that included all nine criterion symptom domains, as well as commonly associated noncriterion symptoms (e.g., anxiety, irritability) (Rush et al, 1986). These 28-item versions were later enlarged to 30 items (Rush et al, 1996) to capture all DSM-IV atypical symptom features (American Psychiatric Association 2000a). The IDS scales were designed to provide a reliable method to measure symptom severity and symptom change, as well as to provide a rapid appraisal of clinically relevant symptom features (e.g., atypical, anxious, melancholic symptoms). The IDS scales have been subjected to numerous psychometric evaluations (Gullion and Rush, 1998; Corruble et al, 1999; Rush et al 2000, 2003, 2004b; Trivedi et al 2004b) and have been administered to patients with major depressive, bipolar, and dysthymic disorders. The 30-item IDS (IDS30) is sensitive to change with various types of treatments (Rush et al 2000, 2003; Trivedi et al 2004a). A recent report (Rush et al 2004b) has shown the performance of the self-report version of the IDS (IDS-SR30) was comparable to the HRSD. Conversion tables allow IDS30 total scores to be converted to equivalent total scores on the 17-item HRSD (HRSD17), 21-item HRSD (HRSD21), and 24-item HRDS (HRSD24) (Rush et al 2003).

To reduce the time needed to appraise depressive symptom severity, the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS16) was developed (Rush et al 2003; Trivedi et al 2004b) in both a clinician-rated (QIDS-C16) and self-report (QIDS-SR16) version. The QIDS can also be administered by computer over the telephone using an IVR system (QIDS-IVR16). All three versions of the QIDS16 scales are based on 16 IDS items and obtain ratings (range 0–3) concerning all nine criterion symptom domains (Rush et al 2003; Trivedi et al 2004b). The questions are identical for the QIDS-C16 and the QIDS-SR16. The QIDS-IVR16 uses slightly different questions to obtain symptom ratings for the nine domains. For all versions of the QIDS, four items are used to assess the sleep domain (initial, middle, and late insomnia, as well as hypersomnia). Two items are used to gauge psychomotor activity (agitation and retardation). Four items assess the appetite/weight domain (i.e., appetite increase and decrease, weight increase and decrease). For each of these three domains, the highest rating on any one relevant item is used to score the domain (range 0 –3). Only one item is used to score the remaining six criterion domains (each rated 0 –3) (sad mood, concentration, energy, interest, guilt, suicidal ideations/intent). The QIDS16 total score ranges from 0 to 27.

The QIDS were designed to measure overall severity of the depressive syndrome (major depressive disorder [MDD]) by assessing each of the nine symptom domains that define the syndrome. The IDS assesses the same nine domains and other commonly associated symptoms (e.g., anxiety, irritability). Neither is intended as a diagnostic tool, though total score thresholds that indicate the presence of MDD have been reported (Rush et al, 1996).

Item response theory (IRT) analyses of QIDS-SR16 data indicate that a QIDS-SR16 total score of 5 corresponds to an HRSD17 total score of 7, a commonly used definition of remission in clinical trials. Other QIDS16 thresholds recommended to estimate depression severity are mild (6 –10), moderate (11–15), severe (16 –20), and very severe (≥21) depression. Corresponding HRSD17 scores would be 8 to 13, 14 to 17, 18 to 24, and ≥25, respectively (Rush et al 2003).

The IDS and QIDS scales are in the public domain and are available in multiple languages (www.ids-qids.org). To date, evidence suggests that both the QIDS-C16 and the QIDS-SR16 have acceptable psychometric properties (Rush et al 2003; Trivedi et al 2004b).

The present study was conducted using data made available by the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (Fava et al 2003; Rush et al 2004a). This report characterizes and compares the QIDS-C16, QIDS-SR16, QIDSIVR16, and the HRSD17 using classical test theory (CTT) and IRT analyses in a large sample of outpatients with MDD.

Methods and Materials

The STAR*D was designed to define prospectively which of several treatments are most effective for outpatients with nonpsychotic MDD who have an unsatisfactory clinical outcome to initial and, if necessary, subsequent treatments. The STAR*D protocol was reviewed and approved by the 14 Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) governing the 14 regional centers and the IRBs at the National Coordinating Center (UT Southwestern, Dallas) and the Data Coordinating Center (University of Pittsburgh) (see acknowledgments and Rush et al 2004a).

Overall Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Outpatients with nonpsychotic MDD were recruited from 18 primary and 23 specialty care settings across the United States. Eligible STAR*D participants were female and male outpatients (18–75 years of age) with nonpsychotic MDD for whom outpatient treatment with an antidepressant was deemed to be safe and appropriate by the treating clinician. The broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria were used to obtain a highly representative sample of persons with MDD treated in everyday practice. Participants with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or anorexia nervosa were excluded, as were those with primary diagnoses of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or bulimia nervosa. Participants with a history of nonresponse or intolerance (in the current major depressive episode) to protocol treatments and those with medical conditions contraindicating protocol treatments (e.g., seizures) were excluded. Participants taking concomitant nonpsychotropic, anxiolytic, or sedative hypnotic medications could enroll based on clinician judgment, and those with current substance abuse or dependence were eligible if inpatient detoxification was not required.

Assessments

Following written informed consent, participants were evaluated by the Clinical Research Coordinators (CRCs), who worked closely with participants and clinicians, administered some of the clinician-rated instruments, ensured that all self-rated instruments were completed, and functioned as study coordinators. Ratings germane to this report are as follows. Telephone interviews with trained and certified research outcome assessors, who were masked to treatment and located apart from any treatment site, collected the HRSD17 and the 30-item IDS clinician rating scale (IDS-C30) (from which the QIDS-C16 was extracted) following a structured interview (available at www.star-d.org). A telephone-based IVR system collected other research outcomes, including the QIDS-IVR16. The patient completed the QIDS-SR16 at the clinic visit.

Statistical Analyses

This preliminary report is based on data available from the first 1500 consecutive STAR*D participants, obtained at entry into or exit from Level 1 (citalopram) treatment. The decision to include data from both the baseline and exit evaluations, rather than just from the baseline evaluations, was arbitrary. The same conclusions result from analyses of either dataset. For this report, data from the HRSD17 and QIDS-C16 extracted from the IDS-C30 obtained by the ROAs, the QIDS-SR16 obtained by the CRC during the clinic visit, and the QIDS-IVR16 obtained by the computer-automated telephone calls were used. All three QIDS16 measures and the HRSD17 must have been obtained within a time period of 2 days or less to be included in these analyses. Of these 1500 participants available, 1120 met the criterion of being administered the QIDS-C16, QIDS-SR16, QIDS-IVR16, and the HRSD17 within 2 days of their baseline visit; 582 had the four tests administered within 2 days of their final (exit) visit; and 479 met both criteria. However, not all patients answered all items, so some analyses involved a smaller number of observations.

Classical test theory measures of scale consistency, including Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951), item score - total scale correlations (not corrected for measurement error), item/symptom domain mean values, and mean total scale scores were computed for each of the four measures of depression. Item response theory analyses of the discriminative and informational relationships between individual scale items and total scale properties were also computed.

An assumption of IRT analysis is that scale items measuring symptom severity assess only depression (i.e., they are unidimensional). Therefore, a principal components factor analysis was conducted on each measure. Parallel analysis (Horn, 1965; Humphreys and Ilgen,, 1969; Humphreys and Montanelli,, 1975; Montanelli and Humphreys,, 1976) was used to infer the number of “real” dimensions (independent components/factors) present in the data. Like a scree plot, parallel analysis is an alternative to the traditional, Kaiser-Guttman rule (eigenvalues greater than 1) to define dimensionality but, unlike the scree criterion, incorporates an empirical rule to define the cutoff.

Parallel analysis involves 1) generating one or more correlation matrices whose individual elements are sampled from a population of null correlations, using the same number of observations and variables as the actual data; 2) extracting the principal components for each random matrix (which are orthogonal, by definition); and 3) averaging the magnitude of the eigenvalues over replications. The number of components for which the obtained eigenvalue exceeds the simulated eigenvalue defines the dimensionality of the variables.

Samejima (1997) graded IRT model item/domain parameters were estimated for each version of the QIDS16 scale and for the HRSD17. To determine whether the parameter estimates varied across the three versions of the QIDS16, the fit of an IRT model in which parameter estimates of all measures were allowed to vary freely was compared with the fit of an IRT model in which parameter estimates were constrained to be the same for each measure.

Effect sizes for change from first to last session of Level 1 were computed for each measure and each item/domain of each measure. Effect size refers to the mean decrease in each item/ domain for those patients (n 1 479) seen on both occasions divided by the standard deviation of the decrease. We chose .50 as an “acceptable” effect size.

The four scales (three versions of the QIDS16 and the HRSD17) were compared on their ability to identify treatment response and remission at exit from Level 1 treatment. The strength of agreement between measures was assessed by the kappa statistic. Treatment response was defined as a 50% improvement from baseline. Remission was defined as HRSD17 score ≥7 or a QIDS16 score ≥5, based on the clinician ratings or the standard self-report or IVR version of the scale (Rush et al, 2003).

Results

Classical Test Theory (CTT) Item Analysis

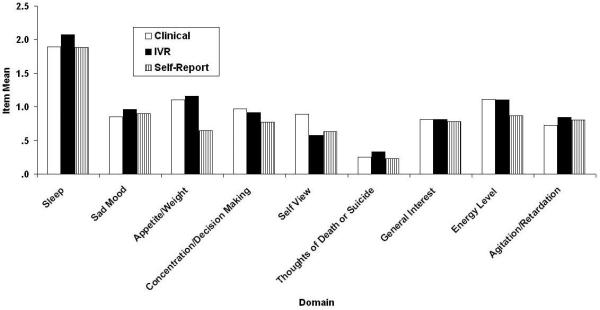

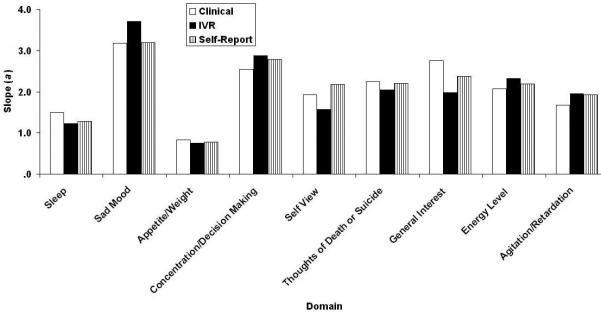

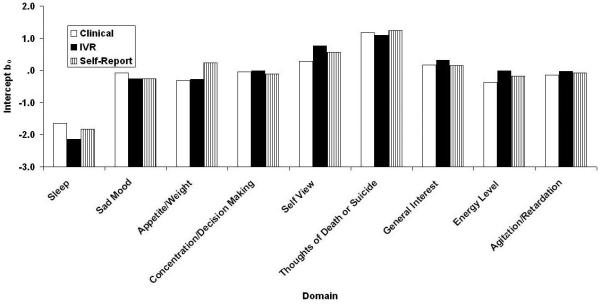

Figures 1 and 2 respectively contain the domain means and the domain item/total correlations (rit) for the three methods of administering the QIDS16 (clinical, self-report, and IVR). One difference not visible in Fig. 2 is that Restlessness/Agitation was never reported at level “3” in the clinical version, whereas it was, albeit rarely in the other two methods.

Figure 1.

QIDS16 domain means as a function of method of administration (clinical, self-report, and IVR). QIDS16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

Figure 2.

QIDS16 domain/total correlations (rit) as a function of method of administration (clinical, self-report, and IVR). QIDS16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

The associated means (standard deviations) were 8.6 (6.3), 7.7 (5.7), and 8.8 (6.4), and the associated values of coefficient alpha were .87, .87, and .86. The mean differences differed significantly, F(2,1162) = 48.13, MSe = 3.99. This is a small effect (η2 = .01), explainable in terms of the lower self-report scores relative to the two others and basically limited to three domains: Appetite, Concentration,/Decision Making, and Energy level, as can be seen in Fig. 1. In general, domains leading to frequent symptom reports in the companion paper (REF??), most specifically Sleep, were also reported frequently here and domains previously reported as correlating highly with the total QIDS16 score also did so here, most specifically Sad Mood and Concentration.

Table 1 contains the item means, item/total correlations (rit), scale mean, scale standard deviation, and coefficient alpha for the HRSD17. Its scale mean (standard deviation) was 11.4 (8.6), and its coefficient alpha reliability was .89. The four measures being considered therefore differ marginally with respect to their internal consistency. Note that although most of the HRSD17 domains correlate acceptably with total score and the reliability is highly similar to the three versions of the QIDS16, Loss of Insight shows virtually no tendency to be reported and the rit for this domain is negative.

Table 1.

QIDS16 Item Means, Scale Means, Scale Standard Deviations, and Coefficients α as a Function of Version (C = Clinical, SR = Self-Report, and IVR = Interactive Voice Relay)

| Domain | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | 1.89 | 1.88 | 2.08 |

| Sad Mood | .85 | .90 | .97 |

| Appetite/Weight | 1.10 | .65 | 1.16 |

| Concentration | .97 | .77 | .91 |

| Self-view | .89 | .63 | .58 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | .25 | .23 | .33 |

| Interest | .81 | .78 | .81 |

| Energy Level | 1.11 | .87 | 1.10 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | .73 | .80 | .84 |

| Scale Mean | 8.8 | 8.6 | 7.5 |

| Scale Standard Deviation | 6.4 | 8.6 | 7.5 |

| Coefficient α | .86 | .87 | .87 |

Intercorrelations among measures

Table 2 contains the intercorrelations among the four measures. Given that the reliabilities were all nearly .9, these correlations essentially become perfect when disattenuated.

Table 2.

QIDS16 Item/Total Correlations as a Function of Version (C = Clinical, SR = Self-Report, and IVR = Interactive Voice Relay)

| Domain | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | .52 | .44 | .47 |

| Sad Mood | .75 | .76 | .74 |

| Appetite/Weight | .39 | .38 | .37 |

| Concentration | .71 | .73 | .74 |

| Self-view | .61 | .51 | .63 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | .52 | .49 | .49 |

| Interest | .74 | .66 | .70 |

| Energy Level | .67 | .70 | .69 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | .57 | .64 | .63 |

Samejima IRT Analysis

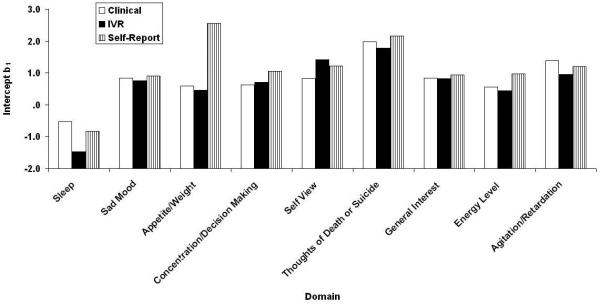

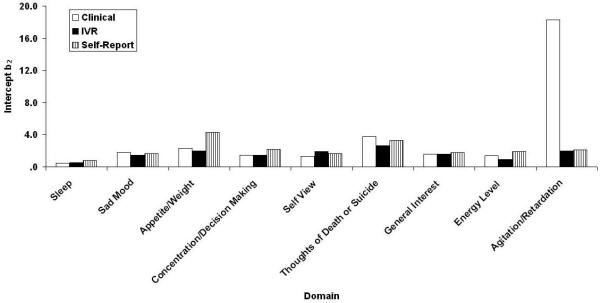

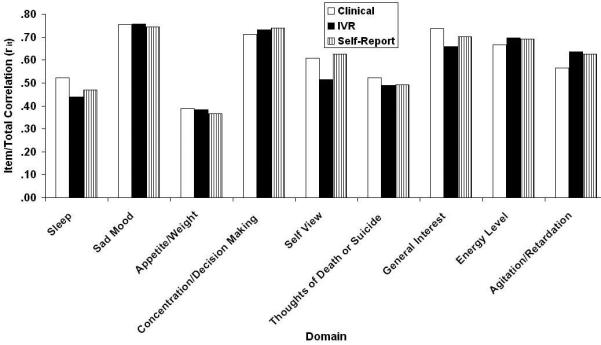

Figs. 3-6 contain the Samejima IRT a, b0, b1, and b2 parameter estimates for the three versions of the QIDS16. It may be recalled from the accompanying paper (REF??) that these represent the slope or relation between the domain and depression in general, the threshold separating category “0” responses from higher category responses, the threshold separating categories “0” or “1” responses from category “2” or “3” responses, and the threshold separating categories “0”, “1”, and “2” responses from category “3”: responses. Like their CTT counterparts, the values are similar across methods of administration with one apparently large exception,: Restlessness/Agitation at b2. In fact, clinicians never used the most extreme response category. Note that the ordinate uses normal-curve scaling—any value outside the range ±3.0 is effectively at asymptote. By this criterion, there were 2, 0, and 2 (7%, 0%, and 7%) extreme b parameter estimates for the clinical, self-report, and IVR results, each of which has a maximum of 27.

Figure 3.

Scree plots for the QIDS-C16, QIDS-SR16, QIDS-IVR16, and HRSD17. QIDS-C16, 16-item Clinician-Rated Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; QIDS-SR16, 16-item Self-Report Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; QIDS-IVR16, 16-item Interactive Voice Response Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; HRSD17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

Figure 6.

QIDS16 b1 location parameter estimates separating 0 and 1 responses from 2 and 3 responses greater than 0 as a function of method of administration (clinical, self-report, and IVR). QIDS16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

Table 3 contains the corresponding Samejima estimates for the HAMD17 (also see REF?? for a similar analysis). Here, a total of 14/51 (27%) parameter estimates were outside the scalable range. Basically, the most extreme response category was never chosen for 12 of 17 items.

Table 3.

HAMD17 Item Means, Item Total Correlations (rit) Scale Means, Scale Standard Deviations, and Coefficients α

| Item | Mean | rit |

|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood | .97 | .76 |

| Guilt feelings and delusions | .91 | .61 |

| Suicide | .30 | .54 |

| Initial insomnia | .73 | .50 |

| Middle insomnia | .94 | .47 |

| Delayed insomnia | .58 | .51 |

| Work and interests | 1.24 | .74 |

| Retardation | .36 | .60 |

| Agitation | .63 | .52 |

| Psychic anxiety | .79 | .68 |

| Somatic anxiety | 1.17 | .58 |

| Appetite | .30 | .43 |

| Somatic energy | .89 | .66 |

| Libido | .73 | .44 |

| Hypochondriasis | .53 | .44 |

| Loss of insight | .03 | −.12 |

| Weight loss | .26 | .24 |

| Scale Mean | 11.4 | |

| Scale Standard Deviation | 8.6 | |

| Coefficient α | .89 |

Inferential tests consist of comparing a model in which all parameters are allowed to vary freely with models containing constraints. The first such constrained model involved equating both the QIDS16 a and b parameters over the three methods of administration. In this case, the fit increased by a significant G2(72) of 779.7 so there are clearly some differences among the three methods of administration. Constraining the b parameters but letting the a parameters vary freely also led to a significant G2(54) of 553.4, so there are clearly large threshold differences. Conversely, constraining the a parameters but letting the b parameters vary freely led to a significant G2(54) of 35.3. Thus, there are some slope differences, but these are of lesser magnitude.

Looking at these differences at the item level indicated that thee slope differences were confined to domains 5 (Self-view) and 7 (General interest), G2(2) o 8.7 and 11.2, ps < .05 and .01. In both cases, IVR was slightly less discriminating than the other two methods. In contrast, only domain 6 (Thoughts of death or suicide) failed to differ across methods at the .05 level or better, and, among the remaining domains, only domain 7 failed to be significant beyond the .01 level.

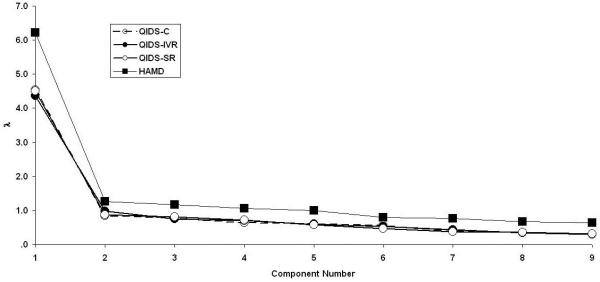

Scale Dimensionalities

Principal component analyses were performed separately upon the three versions of the QIDS16 and the HAMD17. The resulting scree plots (eigenvalue magnitude as a function of its serial position) using the first nine components are presented in Fig. 7. The criterion used to infer how many “real” components were present in the data was parallel analysis (REF??), which has been offered as one alternative to the limitations of the traditional Kaiser-Guttman eigenvalue-greater-than-1 rule. Parallel analysis involves generating a series of correlation matrices sampled from a population of null correlations using the same number of observations and variables as the real data, extracting the principal components for each random matrix, and averaging over replications. The last point where the obtained eigenvalue exceeds the simulated eigenvalue defines the dimensionality. The first four simulated principal components using the 9 variables of the QIDS16 were 1.19, 1.13, 1.08, and 1.03. For each of QIDS16 version, the first obtained eigenvalue for exceeded the first simulated eigenvalue, but all later obtained eigenvalues were smaller than the simulated eigenvalues, which supports the unidimensionality of all three versions. In contrast, the first four simulated principal components using the 17 variables of the HAMD17 were 1.30, 1.24, 1.20, and 1.16. Here, the first two obtained eigenvalues exceeded the simulated eigenvalues, so there is more evidence for multidimensionality of the HAMD17 than the QIDS16.

Figure 7.

QIDS16 b2 location parameter estimates separating 0, 1, and 2 responses from 3 responses as a function of method of administration (clinical, self-report, and IVR). QIDS16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

The elements of the first principal component were then analyzed. These are the optimally weighted linear combinations using z-score transformations of the responses. However, they were virtually identical to the item/total correlations which are the equally weighted linear combinations of the raw response data.

Basline/Exit Changes

The change in item response from baseline to exit was examined next. This represents the mean decrease among the 479 patients seen on both occasions. Tables 4 and 5 contain the data from the three versions of the QIDS16 and the HAMD17, respectively. As can be seen the dominant change, by a large margin, is one of mood.

Table 4.

QIDS-SR16 Item Effect Sizes

| Domain | NEF (n=196) |

CBASP (n=199) |

COMB (n=207) |

Tx Group Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sad Mood | 1.00 | .94 | 1.73 | .21 |

| Concentration | .65 | .64 | 1.10 | .20 |

| Self-view | .67 | .62 | 1.00 | .15 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | .73 | .53 | .77 | .12 |

| Energy | .74 | .80 | 1.29 | .18 |

| Interest | .59 | .63 | 1.14 | .22 |

| Appetite/Weight | .52 | .54 | .57 | .00 |

| Sleep | .70 | .61 | .91 | .12 |

| Psychomotor | .61 | .59 | 1.00 | .14 |

NEF = Nefazodone; CBASP = Cognitive Behavioral System of Psychotherapy; COMB = Combination of NEF and CBASP; Tx = Treatment

Table 5.

Effect Sizes for Baseline to Exit Change and Treatment Group Effect

| NEF (n=196) |

CBASP (n=199) |

COMB (n=207) |

Tx Group Effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| HRSD24 | .43 (.3) | .44 (.2) | .69 (.4) | −.11 (.1) |

| IDS-SR30 | −.58 (.2) | −.54 (.2) | −.85 (.3) | −.12 (.1) |

| QIDS-SR16 | −.69 (.1) | −.66 (.1) | −1.06 (.3) | .15 (.1) |

NEF = Nefazodone; CBASP = Cognitive Behavioral System of Psychotherapy; COMB = Combination of NEF and CBASP; Tx = Treatment

Another way to examine changes is to consider how well pairs of scales agree as to whether a patients has improved, defined as a 50% reduction from baseline. Table 6 contains these data Perhaps not surprisingly, the greatest agreement is that between the two clinically administered scales (the QIDS16-C and HAMD17), which was over 92%. The agreement between the remaining pairs of scales was in the 85-87% range.

Table 6.

Internal Consistencies (Cronbach’s Alpha) at Exit

| QIDS-IVR | .86 |

| QIDS-C16 | .87 |

| QIDS-SR16 | .87 |

| HRSD17 | .89 |

A second definition of change is whether or not a patient can be considered as remitted, defined as a HAMD17 score < 7, a QIDS16-C or QIDS16-SR score < 5, and a QIDS16-IVR score < 6. Table 7 contains the relevant results. Again, the two clinically administered scales agreed most, over 91% of the time, whereas the remaining pairs of scales was in the 85-88% range.

Table 7.

Mean (SD) Total Scores at Exit

| QIDS-IVR | 8.8 (6.4) |

| QIDS-C16 | 8.6 (6.3) |

| QIDS-SR16 | 7.5 (5.6) |

| HRSD17 | 11.4 (8.6) |

Figure 4.

QIDS16 Samejima slope parameter estimates as a function of method of administration (clinical, self-report, and IVR). QIDS16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

Figure 5.

QIDS16 b0 location parameter estimates separating 0 responses from responses greater than 0 as a function of method of administration (clinical, self-report, and IVR). QIDS16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

Table 8.

Correlations among Ratings

| QIDS-C vs. QIDS-IVR | .91 |

| QIDS-C vs. QIDS-SR | .89 |

| QIDS-C vs. HRSD17 | .93 |

| QIDS-SR vs. QIDS-IVR | .89 |

| QIDS-SR vs. HRSD17 | .86 |

| QIDS-IVR vs. HRSD17 | .87 |

Table 9.

HRSD17 Item Total Correlations at Exit

| Item | r |

|---|---|

| Sad Mood | .76 |

| Guilt | .61 |

| Suicide | .54 |

| Initial Insomnia | .50 |

| Middle Insomnia | .47 |

| Late Insomnia | .51 |

| Work/Interest | .74 |

| Retardation | .60 |

| Agitation | .52 |

| Psychic Anxiety | .68 |

| Somatic Anxiety | .58 |

| Appetite | .43 |

| Somatic Energy | .66 |

| Libido | .44 |

| Hypochondriasis | .44 |

| Insight | −.12 |

| Weight Loss | .24 |

Table 10.

HRSD17 Item/Total Correlations

| QIDS-IVR16 Item | HRSD17 Item | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | .47 | Early Insomnia | .50 |

| Middle Insomnia | .47 | ||

| Late Insomnia | .51 | ||

| Sad Mood | .74 | Sad Mood | .76 |

| Appetite/Weight | .37 | Appetite Loss | .48 |

| Weight Loss | .24 | ||

| Energy | .69 | Somatic Energy | .66 |

| Self-view | .63 | Guilt | .61 |

| Interest | .70 | Work/Interest | .74 |

| Psychomotor | 63 | Agitation | .52 |

| Retardation | .60 | ||

| Suicidal Thoughts | .49 | Suicide | .54 |

| Concentration | .74 | ||

| Psychic Anxiety | .68 | ||

| Somatic Anxiety | .58 | ||

| Libido | .44 | ||

| Hypochondriasis | .44 | ||

| Insight | −.12 |

Table 11.

Percentage Respondents with Rating of “0” on Each QIDS Item

| Item | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | 14 | 11 | 14 |

| Sad Mood | 47 | 41 | 41 |

| Appetite/Weight | 45 | 46 | 54 |

| Concentration | 48 | 49 | 46 |

| Self-view | 57 | 69 | 66 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | 81 | 79 | 82 |

| Interest | 55 | 59 | 54 |

| Energy | 39 | 50 | 44 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | 45 | 48 | 47 |

Table 12.

Percentage Respondents with Rating of “1” on Each QIDS Item

| Item | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | 22 | 9 | 17 |

| Sad Mood | 27 | 32 | 36 |

| Appetite/Weight | 16 | 12 | 32 |

| Concentration | 20 | 22 | 34 |

| Self-view | 14 | 14 | 16 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | 13 | 12 | 13 |

| Interest | 19 | 13 | 22 |

| Energy | 27 | 14 | 32 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | 37 | 27 | 33 |

Table 13.

Percentage Respondents with Rating of “2” on Each QIDS Item

| Item | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | 25 | 43 | 37 |

| Sad Mood | 19 | 16 | 15 |

| Appetite/Weight | 24 | 22 | 10 |

| Concentration | 19 | 17 | 17 |

| Self-view | 11 | 7 | 7 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | 6 | 7 | 4 |

| Interest | 16 | 15 | 16 |

| Energy | 18 | 13 | 17 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | 18 | 18 | 14 |

Table 14.

Percentage Respondents with Rating of “3” on Each QIDS Item

| Item | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | 39 | 38 | 32 |

| Sad Mood | 7 | 11 | 8 |

| Appetite/Weight | 16 | 20 | 4 |

| Concentration | 13 | 12 | 3 |

| Self-view | 18 | 10 | 11 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Interest | 10 | 12 | 8 |

| Energy | 16 | 24 | 7 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | 0 | 7 | 7 |

Table 15.

Effect Sizes by Item for the QIDS (Baseline-Exit) (n=479)

| Item | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | .56 | .65 | .53 |

| Sad Mood | 1.14 | 1.22 | 1.14 |

| Appetite/Weight | .33 | .60 | .32 |

| Concentration | .79 | .87 | .79 |

| Self-view | .76 | .77 | .56 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | .48 | .59 | .49 |

| Interest | .80 | .82 | .60 |

| Energy | .70 | .85 | .60 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | .51 | .67 | .53 |

| Total | 1.09 | 1.32 | 1.03 |

Table 16.

Effect Sizes by Item for the HRSD17 (Baseline-Exit) (n=479)

| Item | Effect Size |

Item | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sad Mood | 1.24 | Psychic Anxiety | .66 |

| Guilt | .78 | Somatic Anxiety | .36 |

| Suicide | .47 | Appetite | .44 |

| Initial Insomnia | .51 | Somatic Energy | .73 |

| Middle Insomnia | .57 | Libido | .40 |

| Late Insomnia | .42 | Hypochondriasis | .20 |

| Work/Interest | .80 | Insight | −.03 |

| Retardation | .48 | Weight Loss | .19 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | .35 | Total | 1.10 |

Table 17.

Pattern Elements for the First Principal Component of Each Version of the QIDS

| Item | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | .62 | .53 | .56 |

| Sad Mood | .84 | .84 | .83 |

| Appetite/Weight | .48 | .47 | .45 |

| Concentration | .80 | .82 | .82 |

| Self-view | .71 | .63 | .73 |

| Suicidal Thoughts | .62 | .60 | .59 |

| Interest | .82 | .76 | .79 |

| Energy | .76 | .79 | .77 |

| Psychomotor | .66 | .73 | .72 |

Table 18.

Eigenvalues 1-4 for the Four Measures

| λ 1 | λ 2 | λ 3 | λ 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIDS-C | 4.53 | .84 | .78 | .63 |

| QIDS-SR | 4.51 | .87 | .82 | .72 |

| QIDS-IVR | 4.37 | .98 | .75 | .70 |

| HRSD17 | 6.22 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.06 |

Table 19.

Conversion of HRSD17 to QIDS16 Scores

| HRSD17 | QIDS-C16 | QIDS-SR16 | QIDS-IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| 14 | 11 | 11 | 9 |

| 20 | 15 | 15 | 13 |

| 25 | 19 | 19 | 17 |

| 30 | 22 (−) | 22 | 20 |

Table 20.

Response/Nonresponse Agreements Among Scales1

| A | B | Agree | A+/B− | A−/B+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSD17 | QIDS-IVR16 | 85.2% | 6.3% | 8.6% |

| HRSD17 | QIDS-C16 | 92.5% | 3.8% | 3.8% |

| HRSD17 | QIDS-SR16 | 85.2% | 9.4% | 5.4% |

| QIDS-IVR16 | QIDS-C16 | 87.2% | 7.5% | 5.2% |

| QIDS-IVR16 | QIDS-SR16 | 86.2% | 10.0% | 3.8% |

| QIDS-C16 | QIDS-SR16 | 87.3% | 8.4% | 4.4% |

Response defined as >50% reduction in baseline total score for each scale.

Table 21.

Remission/Nonremission Agreements Among Scales1

| A | B | Agree | A+/B− | A−/B+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSD17 | QIDS-IVR16 | 88.1% | 6.1% | 5.9% |

| HRSD17 | QIDS-C16 | 91.2% | 4.6% | 4.2% |

| HRSD17 | QIDS-SR16 | 83.5% | 6.7% | 9.8% |

| QIDS-IVR16 | QIDS-C16 | 88.1% | 6.1% | 5.9% |

| QIDS-IVR16 | QIDS-SR16 | 85.0% | 5.9% | 9.2% |

| QIDS-C16 | QIDS-SR16 | 86.0% | 5.2% | 8.8% |

Remission was HRSD17 <7; QIDS-C16 <5; QIDS-SR16 <5; QIDS-IVR16 <6.

Table 22.

QIDS-SR16 and QIDS-C16 to Define Response (TMAP)

| QIDS16 Responder Cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| C vs SR Response Agreement |

SR Responder – CRNonresponder |

CR Nonresponder CR Responder |

|

| All Patients (n=544) | 87.3%, K=.68 | 5.9% | 6.8% |

| Nonpsychotic (n=438) | 88.1%, K=.68 | 5.7% | 6.2% |

| Psychotic (n=106) | 84.0%, K=.68 | 6.6% | 9.4% |

Table 23.

QIDS-SR16 and QIDS-C16 to Define Remission (TMAP)

| QIDS16 Remitter Cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| C vs SR Remission Agreement |

SR Remitter – CR Nonremitter |

SR Nonremitter – CR Remitter |

|

| All Patients (n=544) | 93.8%, K = .79 | 3.5% | 2.8% |

| Nonpsychotic (n=438) | 95.0%, K=.84 | 2.7% | 2.3% |

| Psychotic (n=106) | 88.7%, K = .63 | 6.6% | 4.7% |

Table 24.

Effect Size for Baseline to Exit Change and Treatment Group Effect in HRSD24

| Item | NEF (n=196) |

CBASP (n=199) |

COMB (n=207) |

Tx Group Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 – Depressed Mood | −.83 | −.89 | −1.56 | .24 |

| 2 – Guilt Feelings | −.76 | −.74 | −1.23 | .17 |

| 3 – Suicide | −.52 | −.42 | −.75 | .10 |

| 4 – Insomnia (Early) | −.49 | −.29 | −.65 | .14 |

| 5 – Insomnia (Middle) | −.52 | −.50 | −.82 | .10 |

| 6 – Insomnia (Late) | −.42 | −.26 | −.68 | .15 |

| 7 – Work and Activities | −.96 | −.84 | −1.44 | .18 |

| 8 – Retardation | −.26 | −.42 | −.53 | .10 |

| 9 – Agitation | −.23 | −.28 | −.30 | .00 |

| 10 – Anxiety (Psychic) | −.66 | −.73 | −1.09 | .16 |

| 11 – Anxiety (Somatic) | −.48 | −.52 | −.67 | .04 |

| 12 – Somatic Symptoms (Gastrointestinal) | −.05 | −.34 | −.28 | .11 |

| 13 – Somatic Symptoms (General) | −.70 | −.69 | −1.10 | .14 |

| 14 – Genital Symptoms | −.28 | −.27 | −.62 | .16 |

| 15 – Hypochondriasis | −.32 | −.34 | −.43 | .00 |

| 16 – Weight Loss | .13 | −.02 | −.06 | .06 |

| 17 – Insight | −.04 | −.16 | .00 | .06 |

| 18 – Diurnal Variation (Intensity) | −.40 | −.36 | −.69 | .10 |

| 19 – Depersonalization and Derealization | −.16 | −.14 | −.23 | .00 |

| 20 – Paranoid Symptoms | −.15 | −.25 | −.09 | .07 |

| 21 – Obsessional and Compulsive Symptoms | −.07 | −.20 | −.16 | .00 |

| 22 – Helplessness | −.80 | −.55 | −1.11 | .16 |

| 23 – Hopelessness | −.72 | −.52 | −1.09 | .18 |

| 24 – Worthlessness | −.52 | −.72 | −.98 | .12 |

Table 25.

QIDS16 Samejima Slope (a) Parameters as a Function of Version (C = Clinical, SR = Self-Report, and IVR = Interactive Voice Relay)

| Domain | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | 1.49 | 1.28 | 1.23 |

| Sad Mood | 3.18 | 3.19 | 3.71 |

| Appetite/Weight | .83 | .77 | .76 |

| Concentration/Decision Making | 2.55 | 2.79 | 2.88 |

| Self View | 1.93 | 2.17 | 1.57 |

| Thoughts of Death or Suicide | 2.25 | 2.21 | 2.04 |

| General Interest | 2.75 | 2.37 | 1.98 |

| Energy Level | 2.08 | 2.19 | 2.33 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | 1.67 | 1.93 | 1.95 |

Table 26.

Intercepts Separating Responses of 0 from Responses greater than zero as a Function of Version (C = Clinical, SR = Self-Report, and IVR = Interactive Voice Relay)

| Domain | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | −1.65 | −1.84 | −2.14 |

| Sad Mood | −.08 | −.27 | −.26 |

| Appetite | −.31 | .23 | −.27 |

| Concentration/Decision Making | −.04 | −.12 | −.01 |

| Self View | .28 | .57 | .75 |

| Thoughts of Death or Suicide | 1.17 | 1.25 | 1.10 |

| General Interest | .16 | .15 | .31 |

| Energy Level | −.38 | −.17 | −.01 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | −.14 | −.07 | −.02 |

Table 27.

Intercepts Separating Responses of 0 or 1 from Responses greater than 1 as a Function of Version (C = Clinical, SR = Self-Report, and IVR = Interactive Voice Relay)

| Domain | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | −.53 | −.83 | −1.46 |

| Sad Mood | .83 | .91 | .75 |

| Appetite | .59 | 2.55 | .45 |

| Concentration/Decision Making | .63 | 1.06 | .70 |

| Self View | .83 | 1.22 | 1.41 |

| Thoughts of Death or Suicide | 1.98 | 2.16 | 1.79 |

| General Interest | .84 | .94 | .82 |

| Energy Level | .56 | .97 | .45 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | 1.38 | 1.20 | .96 |

Table 28.

Intercepts Separating Responses of 0, 1, or 2 from Responses of 3 as a Function of Version (C = Clinical, SR = Self-Report, and IVR = Interactive Voice Relay)

| Domain | C | SR | IVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | .44 | .78 | .54 |

| Sad Mood | 1.77 | 1.65 | 1.42 |

| Appetite | 2.30 | 4.31 | 2.01 |

| Concentration/Decision Making | 1.42 | 2.18 | 1.45 |

| Self View | 1.29 | 1.65 | 1.90 |

| Thoughts of Death or Suicide | 3.76 | 3.31 | 2.63 |

| General Interest | 1.58 | 1.76 | 1.59 |

| Energy Level | 1.36 | 1.94 | .94 |

| Restlessness/Agitation | 18.28 | 2.08 | 1.96 |

Table 29.

HAMD17 Samejima IRT Parameters

| Domain | a | b0 | b1 | b2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood | 2.84 | −.10 | .72 | 1.31 |

| Guilt feelings and delusions | 1.91 | .17 | .66 | 1.41 |

| Suicide | 2.34 | 1.10 | 1.66 | 2.67 |

| Initial insomnia | 1.26 | .27 | .84 | 21.20 |

| Middle insomnia | 1.05 | −.79 | 1.03 | 25.84 |

| Delayed insomnia | 1.33 | .62 | 1.15 | 18.87 |

| Work and interests | 2.88 | −.17 | .24 | .89 |

| Retardation | 2.25 | .68 | 2.08 | 3.28 |

| Agitation | 1.46 | .23 | 1.43 | 3.33 |

| *Psychic anxiety | 2.22 | .09 | .96 | 1.79 |

| Somatic anxiety | 1.46 | −.97 | .68 | 1.96 |

| Appetite | 1.20 | 1.36 | 2.23 | 20.93 |

| Somatic energy | 2.24 | −.32 | .68 | 13.73 |

| Libido | 1.20 | .27 | .90 | 22.93 |

| Hypochondriasis | 1.18 | .52 | 2.08 | 3.76 |

| Loss of insight | .24 | 17.09 | 19.20 | 31.93 |

| Weight loss | .59 | 2.44 | 5.07 | 40.69 |

Table 30.

Intercorrelations among measures

| QIDS-C | QIDS-IVR | QIDS-SR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QIDS-IVR | .91 | ||

| QIDS-SR | .89 | .89 | |

| HAMD | .93 | .87 | .86 |

Acknowledgements

From the Department of Psychiatry (AJR, MHT, TJC, KS-W, MMB), The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, Texas; Department of Psychology (IHB, AW), The University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, Texas; Epidemiology Data Center (SW), Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Healthcare Technology Systems (JCM), Madison, Wisconsin; and Clinical Psychopharmacology Unit (AAN, MF), Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manualof Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000a. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision) Am J Psychiatry. 2000b;157:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2163–2177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Whybrow PC, Angst F, Versiani M, Moller HJ. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, part 1: Acute and continuation treatment of major depressive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2002a;3:5–43. doi: 10.3109/15622970209150599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Whybrow PC, Angst F, Versiani M, Moller HJ. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, part 2: Maintenance treatment of major depressive disorder and treatment of chronic depressive disorders and subthreshold depressions. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2002b;3:69–86. doi: 10.3109/15622970209150605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P, Allerup P, Gram LF, Reisby N, Rosenberg R, Jacobsen O, et al. The Hamilton Depression Scale. Evaluation of objectivity using logistic models. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63:290–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1981.tb00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Hansen J, Lunde M, Klysner R, Andersen M, Tanghoj P, Solstad K, et al. The validity of the depression rating scales in discriminating between citalopram and placebo in depression recurrence in the maintenance therapy of elderly unipolar patients with major depression. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36:313–316. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Psychiatric Association Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments Clinical Guidelines for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(suppl 1):5S–90S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ, Feinberg M, Smouse PE, Rawson SG, Greden JF. The Carroll Rating Scale for Depression. I. Development, reliability and validation. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;138:194–200. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary P, Guy W. Factor analysis of the Hamilton Depression Scale. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1977;1:115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Corruble E, Legrand JM, Duret C, Charles G, Guelfi JD. IDS-C and IDS-SR: Psychometric properties in depressed in-patients. J Affect Disord. 1999;56:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, Rush AJ, Hirschfeld RM, Kahn DA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: Report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:142–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Depression Guideline Panel . Clinical Practice Guideline, Number 5: Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2. Treatment of Major Depression. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; Rockville, MD: 1993. AHCPR Publication No. 93-0551. [Google Scholar]

- Evans KR, Sills T, DeBrota DJ, Gelwicks S, Engelhardt N, Santor D. An item response analysis of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale using shared data from two pharmaceutical companies. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli C, Albanesi G, Poli E. Assessment of depression: A comparison of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 1986;11:245–253. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faries D, Herrera J, Rayamajhi J, DeBrota D, Demitrack M, Potter WZ. The responsiveness of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J PsychiatrRes. 2000;34:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(99)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26:457–494. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Clark DC, Kupfer DJ. Exactly what does the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale measure? J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27:259–273. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullion CM, Rush AJ. Toward a generalizable model of symptoms in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:959–972. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi E, Amin Y, Abou-Saleh MT. Performance of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in depressed patients in the United Arab Emirates. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96:416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL. An empirical comparison of various methods for estimating common factor scores. Educ Psychol Meas. 1965;25:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys LG, Ilgen D. Note on a criterion for the number of common factors. Educ Psychol Meas. 1969;29:571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys LG, Montanelli RG., Jr An investigation of the parallel analysis criterion for determining the number of common factors. Multivariate Behav Res. 1975;10:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL. Effect size as a measure of symptom-specific drug change in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos T, Salamero M. Factor study of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and the Bech Melancholia Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82:178–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller HJ. Methodological aspects in the assessment of severity of depression by the Hamilton Depression Scale. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251(suppl 2):II13–I120. doi: 10.1007/BF03035121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanelli RG, Jr, Humphreys LG. Latent roots of random data correlation matrices with squared multiple correlations on the diagonal: A Monte Carlo Study. Psychometrika. 1976;41:341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Ä sberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pancheri P, Picardi A, Pasquini M, Gaetano P, Biondi M. Psychopathological dimensions of depression: A factor study of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in unipolar depressed outpatients. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reesal RT, Lam RW, CANMAT Depression Work Group Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. II. Principles of management. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(suppl 1):21S–28S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, Kobak KA. Reliability and validity of the Hamilton Depression Inventory: A paper and pencil version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale clinical interview. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:472–483. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Carmody TJ, Reimitz PE. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Clinician (IDS-C) and self-report (IDS-SR) ratings of depressive symptoms. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2000;9:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi MH, Sackeim HA, et al. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): Rationale and design. Control Clin Trials. 2004a;25:119–142. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C. The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 1986;18:65–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Ryan ND. Current and emerging therapeutics for depression. In: Davis KL, Charney D, Coyle JT, Nemeroff C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology. The Fifth Generation of Progress. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2002. pp. 1081–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Carmody TJ, Ibrahim H, Markowitz JC, Keitner GI, et al. Self-reported depressive symptom measures: Sensitivity to detecting change in a randomized, controlled trial of chronically depressed, nonpsychotic outpatients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004b;30(2):405–416. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. Graded response model. In: van Linden W, Hambleton RK, editors. Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1997. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Smouse PE, Feinberg M, Carroll BJ, Park MH, Rawson SG. The Carroll Rating Scale for Depression. II. Factor analyses of the feature profiles. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;138:201–204. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanborg, sberg M. A comparison between the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the Montgomery Ä sberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) J Affect Disord. 2001;64:203–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Crismon ML, Kashner TM, Toprac MG, Carmody TJ, et al. Clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004a;61:669–680. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: A psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004b;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]