Abstract

Most commonly, coronary artery aneurysms are secondary to atherosclerosis, but cases have been reported in patients who have vasculitis or tissue disorders, and in patients who have undergone interventional procedures. However, over the past few years, an increasing number of cases of coronary artery aneurysms after drug-eluting stent implantation have been reported. The exact mechanism is unknown. Experimental animal studies have shown that both the active drug and the polymer coating, under certain circumstances, might cause progressive luminal dilation, positive vascular remodeling, and aneurysmal formation. Complications like rupture, thrombosis, embolization, myocardial infarction, and even sudden death have been reported. Treatment options vary from aggressive surgical ligation of the aneurysm, in union with distal bypass surgery, to percutaneous implantation of a covered stent or conservative medical management with continued antiplatelet therapy. Currently, there is no consensus on an ideal approach to treating coronary artery aneurysm after drug-eluting stent implantation. Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents, easy and rapid to deploy, have emerged as a newer option. We report a case of coronary artery aneurysm at the site of a previous drug-eluting stent. The lesion was successfully treated with a polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent.

Key words: Blood vessel prosthesis; coronary aneurysm/etiology/therapy; coronary disease/therapy; covered stents; dilatation, pathologic; drug delivery systems/adverse effects; drug-eluting stents/adverse effects; polytetrafluoroethylene; postoperative complications; sirolimus/administration & dosage; stents/adverse effects

Aneurysmal dilation of the coronary arteries was first described by Bougon in 1812.1 Most commonly, coronary artery aneurysms are secondary to atherosclerosis,2 but cases have been reported in patients who have vasculitis (Kawasaki syndrome,3 for example) or tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos4 or Marfan syndrome,5 for example), and in patients who have undergone interventional procedures.6,7 Over the past few years, an increasing number of case reports have described a growing incidence of coronary artery aneurysms after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation.8–11 Since 2003, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the 1st such stent, DESs have unequivocally demonstrated their superiority to bare-metal stents in regard to in-stent restenosis.9–12 Nevertheless, safety concerns brought up from time to time—especially regarding the increased risk of late stent thrombosis13—have raised questions about the long-term safety of DES implantations.

The exact mechanism of coronary artery aneurysmal formation after DES placement is unknown. Complications such as rupture,14 thrombosis,15 distal embolization,16 myocardial infarction,17 and even sudden death18 have been reported. Here we report a case of coronary artery aneurysm at the site of DES implantation, which we successfully treated with a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stent. In addition, we present a review of the literature on the use of PTFE-covered stents in the repair of coronary artery aneurysms that have formed at the site of DES implantation.

Case Report

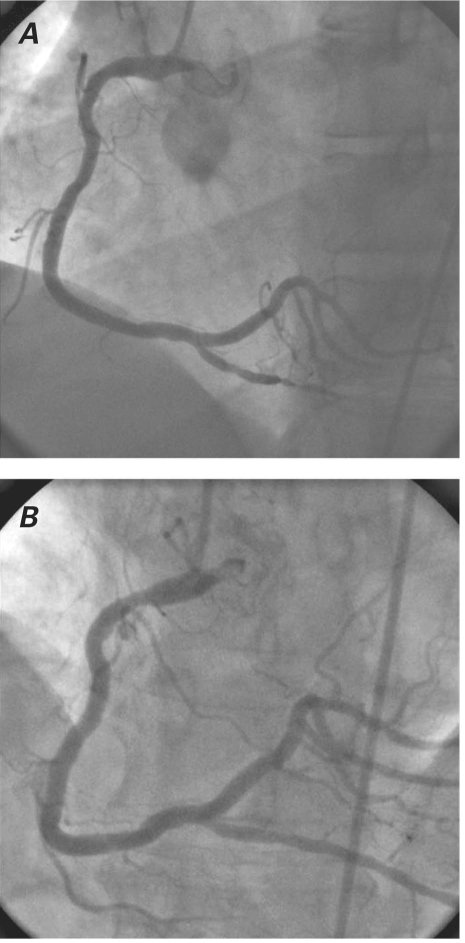

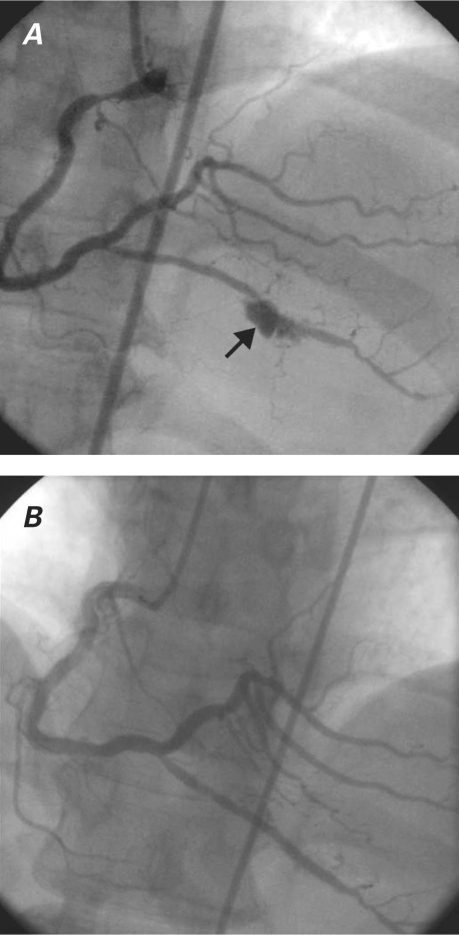

In May 2006, a 47-year-old man with a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking—and a family history positive for coronary artery disease—was referred to our institution for emergent cardiac catheterization due to a diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiac catheterization revealed 90% stenosis of the posterior descending coronary artery (PDCA) (Fig. 1A). The lesion was treated successfully with a sirolimus-eluting stent (Fig. 1B). After 1 year, the patient presented again at the hospital with exertional chest tightness of 1 month's duration, which had gotten worse over that time. An electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with no ST-T changes and with Q waves in leads III and aVF. Cardiac catheterization revealed 80% stenosis in the proximal right coronary artery (RCA) and a large PDCA aneurysm at the previous stent site, with 70% to 80% stenosis distal to the stent (Fig. 2A). In consideration of the aneurysm's size, we decided to repair it with a covered stent.

Fig. 1 Coronary angiograms (both left anterior oblique view) show A) posterior descending coronary artery stenosis and B) resolution of posterior descending coronary artery stenosis after the implantation of a drug-eluting stent.

Fig. 2 Coronary angiography A) in right anterior oblique view shows proximal right coronary artery stenosis and aneurysmal formation after 1 year, at the site of the drug-eluting stent (arrow); and B) in anteroposterior view shows resolution of the coronary artery aneurysm after implantation of a covered stent.

Eptifibatide was given during the procedure. An 8F JR4 guiding catheter was used. A 0.014-in Hi-Torque Balance Middle Weight guidewire (Abbott Vascular, part of Abbott Laboratories; Abbott Park, Ill) was advanced across the lesions in the RCA and the PDCA. A 2.5 × 15-mm VOYAGER™ balloon (Abbott Vascular) was used to dilate the PDCA lesion at 6 atm. A 3 × 19-mm PTFE-covered stent, the JOSTENT® GraftMaster (Abbott Vascular), was deployed at 12 atm across the mid-PDCA lesion. The post-stent angiogram revealed a well-deployed stent in the PDCA with no residual stenosis, no residual aneurysm, and good distal flow (Fig. 2B). A 4 × 15-mm VISION™ stent (Abbott Vascular) was deployed at 14 atm across the proximal RCA lesion. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital on aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, atorvastatin, and enalapril. After 2 years of follow-up, the patient underwent an exercise Cardiolite® stress test (Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc.; N. Billerica, Mass), which revealed an ejection fraction of greater than 0.70 and no evidence of reversible ischemia. The patient has been regularly monitored in our cardiology clinic and has been doing well.

Discussion

Coronary artery aneurysms have been defined as localized coronary dilations with diameters at least 1.5 times the diameters of adjacent normal coronary segments. Coronary artery aneurysms are relatively uncommon and are usually identified incidentally during angiography. The incidence ranges widely, from 0.3% to 4.5%.3,19 A close review of the available literature makes it apparent that coronary artery aneurysms, increasingly, are being found at DES implantation sites.8,11

In our patient, a sirolimus-eluting stent had been placed. Sirolimus-eluting stents are balloon-expandable, intracoronary, 316L stainless-steel stents that are composed of iron, nickel, chromium, and molybdenum, coated with polymethacrylates and polyolefin copolymers. These polymers elute sirolimus gradually at the local site, causing a sustained suppression of vascular smooth muscle and neointimal proliferation. Sirolimus—the immunosuppressive ingredient—elutes completely over a period of a few months, whereas the other stent components persist in the vascular wall.

The exact mechanism of coronary aneurysmal formation is unknown, but several hypotheses have been proposed. In biopsied aneurysmal segments, hypersensitivity vasculitis—characterized by an extensive inflammatory infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and eosinophils—has been found to involve the intima, media, and adventitia.13 Although the stainless-steel stents and the non-erodible polymers used for drug delivery are considered to be highly biocompatible, these have been known to interact adversely with the anti-proliferative drugs that they carry. Experimental animal studies have shown that the active drug,20,21 as well as the polymer coating,22,23 can under certain circumstances damage the vessel through progressive luminal dilation, positive vascular remodeling, aneurysmal formation, and even, at times, rupture.

Treatment options vary: aggressive surgical ligation of the aneurysm accompanied by distal bypass surgery,10 percutaneous covered stenting,9 and conservative medical management with continued antiplatelet therapy.8 Yet there is no consensus on an ideal approach to use in patients who develop coronary artery aneurysm after DES implantation. Percutaneous treatment is a newer option that involves the placement of a covered stent to obstruct blood flow into the aneurysmal sac. The synthetic membrane of the stent-graft effectively prevents plaque protrusion, successfully sealing the aneurysm—a safer and less invasive alternative in the treatment of coronary aneurysms. These PTFE-covered stents, easy and rapid to deploy, have emerged as a new tool for the treatment of coronary artery aneurysms,24,25 coronary perforations or ruptures,26,27 coronary artery fistulae,28 saphenous vein graft disease,29 carotid artery aneurysms,30 and aortic and peripheral vascular disease.31,32

Polytetrafluoroethylene has ideal characteristics as a single layer, and it can be rolled to form a thin multilayer covering that can be expanded 4 to 5 times its original diameter (when the stent expands) without laceration or shrinkage. Furthermore, the negative charge of the polymer prevents blood-protein coagulation on the tissue surface and limits platelet activation and thrombus formation.33 Chemically composed of carbon chains saturated with fluorine, PTFE for vascular prosthetic applications is known as expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). Expansion is part of the manufacturing process, in which the solid material is modified into a porous lattice. When ePTFE is used to cover a balloon-expandable metal stent, the material dilates simultaneously with the stent, with a resulting decrease in the thickness of the material wall. To avoid disruption of the ePTFE during deployment, the total balloon length, including the tapered ends, should match the length of the ePTFE membrane.34 Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents for coronary and saphenous vein graft use have been developed by Boston Scientific Corporation (the Symbiot® stent, consisting of a double layer of ePTFE surrounding a modified self-expanding RADIUS-like nitinol stent), by Abbott Vascular (the JOSTENT Coronary Stent Graft, consisting of a single ePTFE layer sandwiched between 2 stents), and by CardioVasc Inc. (now Nfocus Neuromedical, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif, maker of the NuVasc® Stent-Graft, a stainless-steel stent surrounded by ePTFE coated with the synthetic peptide P-15, a cell adhesion protein to promote endothelialization).35 However, some multicenter randomized trials, in comparing ePTFE stent-grafts with bare-metal stents, have shown that these stents do not improve clinical outcomes and may be associated with a higher incidence of restenosis and early thrombosis.36

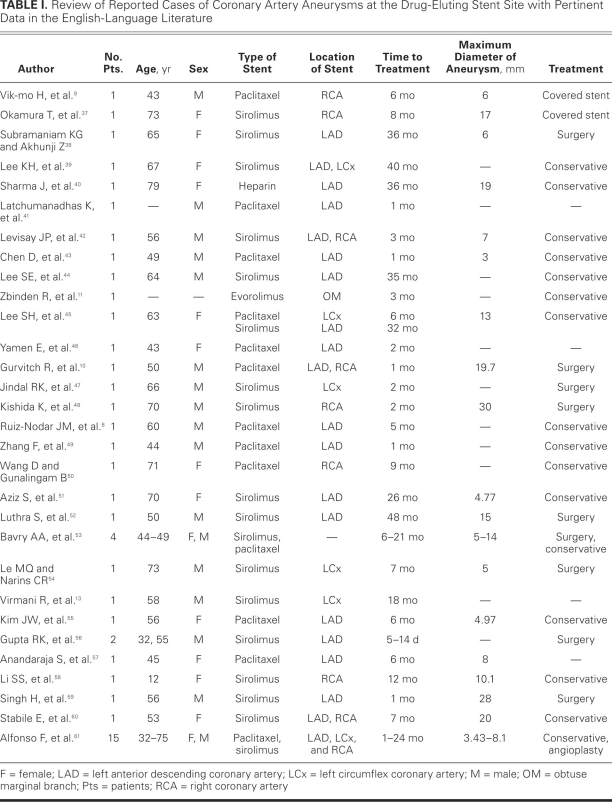

On reviewing the available data in the English-language literature (Table I),8–11,13,37–61 we encountered only 2 previously reported cases in which PTFE-covered stents were used exclusively in the repair of coronary artery aneurysms at the DES site. Vik-Mo and colleagues9 described the case of a 43-year-old man who developed an RCA aneurysm 6 months after receiving a paclitaxel-eluting stent. Angiography and intracoronary ultrasonography revealed a lack of contact between the stent and the vascular wall in a 15-mm-long segment with a maximal aneurysmal diameter of 6 mm. The patient was successfully treated with implantation of a covered stent (JOMED Implantate, Abbott Vascular). Okamura and associates37 described the case of a 73-year-old woman who was found to have a large, eccentric saccular RCA aneurysm (17 × 9 mm) at the site of a sirolimus-eluting stent that had been implanted 8 months before the presentation. The aneurysmal opening was sealed with a PTFE-covered stent.

TABLE I. Review of Reported Cases of Coronary Artery Aneurysms at the Drug-Eluting Stent Site with Pertinent Data in the English-Language Literature

In conclusion, we have presented the case of a 47-year-old man who developed a large aneurysm at the stent site 1 year after receiving a sirolimus-eluting stent in the PDCA branch of the RCA. The aneurysm was successfully treated with a PTFE-covered stent deployed via the percutaneous approach. Although intravascular ultrasonography was not performed in this particular patient, the aneurysm was large enough to prompt our decision to repair it with a covered stent. Had the coronary artery aneurysm been small (with lower risk of rupture), conservative management with dual antiplatelet therapy might have been appropriate. Similarly, if we had encountered a large aneurysm with risk of impending rupture, surgical repair might have been more appropriate. One of the limitations of our case study is that no repeat angiography was done after stent placement, because the patient was doing well clinically and because a noninvasive follow-up, in the form of an exercise Cardiolite stress test, had shown no reversible ischemia and a good ejection fraction.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Sharad Bajaj, MD, 175 Overmount Ave., Apt. D, West Paterson, NJ 07424

E-mail: drsharadbajaj@gmail.com

References

- 1.Jarcho S. Bougon on coronary aneurysm (1812). Am J Cardiol 1969;24(4):551–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Oliveros RA, Falsetti HL, Carroll RJ, Heinle RA, Ryan GF. Atherosclerotic coronary artery aneurysm. Report of five cases and review of literature. Arch Intern Med 1974;134(6):1072–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Burns JC, Shike H, Gordon JB, Malhotra A, Schoenwetter M, Kawasaki T. Sequelae of Kawasaki disease in adolescents and young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28(1):253–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Di Mario C, Zanchetta M, Maiolino P. Coronary aneurysms in a case of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Jpn Heart J 1988;29(4): 491–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Onoda K, Tanaka K, Yuasa U, Shimono T, Shimpo H, Yada I. Coronary artery aneurysm in a patient with Marfan syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72(4):1374–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bell MR, Garratt KN, Bresnahan JF, Edwards WD, Holmes DR Jr. Relation of deep arterial resection and coronary artery aneurysms after directional coronary atherectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20(7):1474–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sabate M, Serruys PW, van der Giessen WJ, Ligthart JM, Coen VL, Kay IP, et al. Geometric vascular remodeling after balloon angioplasty and beta-radiation therapy: a three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 1999; 100(11):1182–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ruiz-Nodar JM, Valencia J, Pineda J. Coronary aneurysms after drug-eluting stents implantation. Eur Heart J 2007;28 (23):2826. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Vik-Mo H, Wiseth R, Hegbom K. Coronary aneurysm after implantation of a paclitaxel-eluting stent. Scand Cardiovasc J 2004;38(6):349–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gurvitch R, Yan BP, Warren R, Marasco S, Black AJ, Ajani AE. Spontaneous resolution of multiple coronary aneurysms complicating drug eluting stent implantation. Int J Cardiol 2008;130(1):e7–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zbinden R, Eshtehardi P, Cook S. Coronary aneurysm formation in a patient early after everolimus-eluting stent implantation. J Invasive Cardiol 2008;20(5):E174–5. [PubMed]

- 12.Ako J, Morino Y, Honda Y, Hassan A, Sonoda S, Yock PG, et al. Late incomplete stent apposition after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: a serial intravascular ultrasound analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46(6):1002–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, Musumeci G, Grieco N, Motta T, et al. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus-eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation 2004;109(6):701–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.van Suylen RJ, Serruys PW, Simpson JB, de Feyter PJ, Strauss BH, Zondervan PE. Delayed rupture of right coronary artery after directional atherectomy for bail-out. Am Heart J 1991; 121(3 Pt 1):914–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Fareh S, Tabib A, Julie C, Loire R. Large coronary artery aneurysms. A study of 20 clinical cases in the elderly [in French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 1997;90(4):431–8. [PubMed]

- 16.Gziut AI, Gil RJ. Coronary aneurysms. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2008;118(12):741–6. [PubMed]

- 17.Sumino H, Kanda T, Sasaki T, Kanazawa N, Takeuchi H. Myocardial infarction secondary to coronary aneurysm in systemic lupus erythematosus. An autopsy case. Angiology 1995;46(6):527–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Walsh J, Siklos P, Al-Rufaie HK. Massive aneurysm of the right coronary artery causing sudden death. Int J Cardiol 1998;64(2):213–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, Vignola PA, Judkins MP, Kemp HG, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation 1983;67(1):134–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Farb A, Heller PF, Shroff S, Cheng L, Kolodgie FD, Carter AJ, et al. Pathological analysis of local delivery of paclitaxel via a polymer-coated stent. Circulation 2001;104(4):473–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Heldman AW, Cheng L, Jenkins GM, Heller PF, Kim DW, Ware M Jr, et al. Paclitaxel stent coating inhibits neointimal hyperplasia at 4 weeks in a porcine model of coronary restenosis. Circulation 2001;103(18):2289–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Serruys PW, Degertekin M, Tanabe K, Abizaid A, Sousa JE, Colombo A, et al. Intravascular ultrasound findings in the multicenter, randomized, double-blind RAVEL (RAndomized study with the sirolimus-eluting VElocity balloon-expandable stent in the treatment of patients with de novo native coronary artery Lesions) trial. Circulation 2002;106(7):798–803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Curcio A, Torella D, Cuda G, Coppola C, Faniello MC, Achille F, et al. Effect of stent coating alone on in vitro vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286(3):H902–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Szalat A, Durst R, Cohen A, Lotan C. Use of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent for treatment of coronary artery aneurysm. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005;66(2):203–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Lee MS, Nero T, Makkar RR, Wilentz JR. Treatment of coronary aneurysm in acute myocardial infarction with AngioJet thrombectomy and JoStent coronary stent graft. J Invasive Cardiol 2004;16(5):294–6. [PubMed]

- 26.Briguori C, Nishida T, Anzuini A, Di Mario C, Grube E, Colombo A. Emergency polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent implantation to treat coronary ruptures. Circulation 2000; 102(25):3028–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ly H, Awaida JP, Lesperance J, Bilodeau L. Angiographic and clinical outcomes of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent use in significant coronary perforations. Am J Cardiol 2005;95 (2):244–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Balanescu S, Sangiorgi G, Medda M, Chen Y, Castelvecchio S, Inglese L. Successful concomitant treatment of a coronary-to-pulmonary artery fistula and a left anterior descending artery stenosis using a single covered stent graft: a case report and literature review. J Interv Cardiol 2002;15(3):209–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ho PC, Leung CY. Treatment of post-stenotic saphenous vein graft aneurysm: special considerations with the polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent. J Invasive Cardiol 2004;16(10):604–5. [PubMed]

- 30.Saatci I, Cekirge HS, Ozturk MH, Arat A, Ergungor F, Sekerci Z, et al. Treatment of internal carotid artery aneurysms with a covered stent: experience in 24 patients with mid-term follow-up results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25(10):1742–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Pershad A, Heuser R. Renal artery aneurysm: successful exclusion with a stent graft. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2004;61 (3):314–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Butera G, Piazza L, Chessa M, Negura DG, Rosti L, Abella R, et al. Covered stents in patients with complex aortic coarctations. Am Heart J 2007;154(4):795–800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Di Mario C, Inglese L, Colombo A. Treatment of a coronary aneurysm with a new polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stent: a case report. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 1999;46(4):463–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Palmaz JC. Review of polymeric graft materials for endovascular applications. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1998;9(1 Pt 1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Jamshidi P, Mahmoody K, Erne P. Covered stents: a review. Int J Cardiol 2008;130(3):310–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Schachinger V, Hamm CW, Munzel T, Haude M, Baldus S, Grube E, et al. A randomized trial of polytetrafluoroethylene-membrane-covered stents compared with conventional stents in aortocoronary saphenous vein grafts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42(8):1360–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Okamura T, Hiro T, Fujii T, Yamada J, Fukumoto Y, Hashimoto G, et al. Late giant coronary aneurysm associated with a fracture of sirolimus eluting stent: a case report. J Cardiol 2008;51(1):74–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Subramaniam KG, Akhunji Z. Drug eluting stent induced coronary artery aneurysm repair by exclusion. Where are we headed? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;36(1):203–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Lee KH, Lee SR, Jin GY, Lee SH, Rhee KS, Chae JK, et al. Double coronary artery stent fracture with coronary artery microaneurysms. Int Heart J 2009;50(1):127–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Sharma J, Kanei Y, Kwan TW. A case of giant coronary artery aneurysm after placement of a heparin-coated stent. J Invasive Cardiol 2009;21(2):E22–3. [PubMed]

- 41.Latchumanadhas K, Venkatesan KG, Juneja S, Mullasari SA. Early coronary aneurysm with paclitaxel-eluting stent. Indian Heart J 2006;58(1):57–60. [PubMed]

- 42.Levisay JP, Roth RM, Schatz RA. Coronary artery aneurysm formation after drug-eluting stent implantation. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2008;9(4):284–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Chen D, Chang R, Ho AT, Frivold G, Foster G. Spontaneous resolution of coronary artery pseudoaneurysm consequent to percutaneous intervention with paclitaxel-eluting stent. Tex Heart Inst J 2008;35(2):189–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Lee SE, John SH, Lim JH, Rhew JY. Very late stent thrombosis associated with multiple stent fractures and peri-stent aneurysm formation after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circ J 2008;72(7):1201–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Lee SH, Chae JK, Ko JK. Consecutively developed late stent malappositions following the implantation of two different kinds of drug-eluting stents associated with spontaneous healing. Int J Cardiol 2009;134(1):e7–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Yamen E, Brieger D, Kritharides L, Saw W, Lowe HC. Late incomplete apposition and coronary artery aneurysm formation following paclitaxel-eluting stent deployment: does size matter? J Invasive Cardiol 2007;19(10):449–50. [PubMed]

- 47.Jindal RK, George R, Singh B. Giant coronary aneurysm following drug-eluting stent implantation presenting as fever of unknown origin. J Invasive Cardiol 2007;19(7):313–4. [PubMed]

- 48.Kishida K, Nakaoka H, Sumitsuji S, Nakatsuji H, Ihara M, Nojima Y, et al. Successful surgical treatment of an infected right coronary artery aneurysm-to-right ventricle fistula after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Intern Med 2007;46 (12):865–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Zhang F, Qian JY, Ge JB. Rapid development of late stent malappositon and coronary aneurysm following implantation of a paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120(7):614–6. [PubMed]

- 50.Wang D, Gunalingam B. Coronary artery aneurysms associated with a paclitaxel coated stent. Heart Lung Circ 2008;17 (1):66–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Aziz S, Morris JL, Perry RA. Late stent thrombosis associated with coronary aneurysm formation after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. J Invasive Cardiol 2007;19(4):E96–8. [PubMed]

- 52.Luthra S, Tatoulis J, Warren RJ. Drug-eluting stent-induced left anterior descending coronary artery aneurysm: repair by pericardial patch–where are we headed? Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83(4):1530–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Bavry AA, Chiu JH, Jefferson BK, Karha J, Bhatt DL, Ellis SG, Whitlow PL. Development of coronary aneurysm after drug-eluting stent implantation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146 (3):230–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Le MQ, Narins CR. Mycotic pseudoaneurysm of the left circumflex coronary artery: a fatal complication following drug-eluting stent implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007; 69(4):508–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Kim JW, Seo HS, Suh SY, Rha SW, Park CG, Oh DJ. Spontaneous resolution of neoaneurysm following implantation of a paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent. Int J Cardiol 2006;112(2): e12–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Gupta RK, Sapra R, Kaul U. Early aneurysm formation after drug-eluting stent implantation: an unusual life-threatening complication. J Invasive Cardiol 2006;18(4):E140–2. [PubMed]

- 57.Anandaraja S, Naik N, Talwar K. Coronary artery aneurysm following drug-eluting stent implantation. J Invasive Cardiol 2006;18(1):E66–7. [PubMed]

- 58.Li SS, Cheng BC, Lee SH. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Giant coronary aneurysm formation after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation in Kawasaki disease. Circulation 2005; 112(8):e105–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Singh H, Singh C, Aggarwal N, Dugal JS, Kumar A, Luthra M. Mycotic aneurysm of left anterior descending artery after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: a case report. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005;65(2):282–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Stabile E, Escolar E, Weigold G, Weissman NJ, Satler LF, Pichard AD, et al. Marked malapposition and aneurysm formation after sirolimus-eluting coronary stent implantation. Circulation 2004;110(5):e47–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Alfonso F, Perez-Vizcayno MJ, Ruiz M, Suarez A, Cazares M, Hernandez R, et al. Coronary aneurysms after drug-eluting stent implantation: clinical, angiographic, and intravascular ultrasound findings. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53(22):2053–60. [DOI] [PubMed]