Abstract

Importance of the field

Osteoporosis has become a worldwide health and social issue due to an aging population. Four major antiresorptive drugs (agents capable of inhibiting osteoclast formation and/or function) are currently available on the market: estrogen, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), bisphosphonates and calcitonin. These drugs either lack satisfactory efficacy or have potential to cause serious side effects. Thus, development of more efficacious and safer drugs is warranted.

Areas covered in this review

The discovery of the receptor activator of NF-κB Ligand (RANKL) and its two receptors, RANK and osteoprotegerin (OPG), has not only established a crucial role for the RANKL/RANK/OPG axis in osteoclast biology but also created a great opportunity to develop new drugs targeting this system for osteoporosis therapy. This review focuses on discussion of therapeutic targeting of RANK signaling.

What the reader will gain

An update on the functions of RANKL and an overview of the known RANK signaling pathways in osteoclasts. A discussion of rationales for exploring RANK signaling pathways as potent and specific therapeutic targets to promote future development of better drugs for osteoporosis.

Take home message

Several RANK signaling components have the potential to serve as potent and specific therapeutic targets for osteoporosis.

Keywords: Antiresorptive Drug, Osteoclast, Osteoporosis, RANKL, RANK, OPG, Therapeutic Target

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of the skeleton, resulting in bone fragility and an increased susceptibility to fractures [1]. Rather than a single entity, osteoporosis refers to a group of distinct pathological conditions that leads to bone fragility and increased risk of fracture. These medical conditions can be categorized into either primary or secondary osteoporosis [1, 2]. Primary osteoporosis further consists of two subtypes: postmenopausal osteoporosis and senile osteoporosis [3, 4]. Postmenopausal osteoporosis is primarily caused by the decline in estrogen levels associated with menopause, whereas senile osteoporosis is mainly associated with aging. Secondary osteoporosis is a distinct group of bone disorders which are the result of a large number of other medical conditions or therapeutic interventions of certain disorders [1, 2].

Regardless of cause, osteoporosis reflects an imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation in favor of bone resorption. Thus, effective inhibition of bone resorption has long been recognized as an important therapeutic strategy for osteoporosis. The osteoclast, the sole bone resorbing cell, normally plays a pivotal role in skeletal development and maintenance [5]. However, when its formation, activity and/or survival is aberrantly elevated, the osteoclast can play a role in the pathogenesis of a variety of bone disorders including osteoporosis [6, 7], bone erosion in inflammatory conditions [8, 9] and tumor-induced osteolysis [10]. Currently, there are four major antiresorptive drugs (agents capable of inhibiting osteoclast formation and/or function) on the market: estrogen [11], selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) [12], bisphosphonates [13], and calcitonin [14, 15]. However, these drugs either lack satisfactory efficacy or have potential to cause serious side effects in clinical management of postmenopausal osteoporosis [15–18]. Moreover, as the population continues to age, osteoporosis is likely to become an even more prevalent and serious health and societal problem. Thus, more efficacious and safer antiresorptive drugs are urgently needed.

The discovery of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system in the late 1990s has not only greatly advanced our understanding of osteoclast biology but has also created enthusiasm for developing therapeutic agents targeting the system for osteoporosis therapy [19]. Initial attempts have been focused on OPG, RANK-Fc and anti-RANKL antibodies [20–22], which all function to block the RANKL-RANK interaction. Encouragingly, these efforts have led to a successful development of a high affinity anti-RANKL antibody (denosumab) by Amgen Inc, which holds great therapeutic potential [23–25] and is currently awaiting the approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

The prospect of denosumab becoming a new drug for treating osteoporosis further shows the great potential of the RANKL/RANK/OPG axis to serve as a therapeutic target for various bone disorders. On the other hand, agents that block the RANKL-RANK interaction all share a potential drawback - lack of specificity due to the involvement of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system in a variety of other biological processes. Thus, it is necessary to continue to searching for better strategies to achieve more specific and effective targeting of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system. This review intends to discuss what is known about RANK signaling pathways involved in osteoclast biology and which components of the known RANK signaling pathways have the potential to serve as therapeutic targets for osteoporosis therapy. We will also briefly describe key future studies needed to further validate these therapeutic targets and potential experimental strategies to identify compounds against these targets. We hope that this discussion will promote more enthusiasm towards exploring RANK signaling pathways in order to better target the RANKL/RANK/OPG axis for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis.

2.0 The RANKL/RANK/OPG System

2.1 Discovery and Known Functions of the RANKL/RANK/OPG System

RANKL, also known as OPGL, ODF and TRANCE, was discovered independently by two bone biology groups [26, 27] and two immunology groups [28, 29] in the late 1990s. RANKL is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily and exerts its functions by binding and activating its receptor RANK, which belongs to the TNF receptor (TNFR) superfamily [28]. OPG is a soluble decoy receptor for RANKL and inhibits RANKL functions by competing with RANK for binding RANKL [30, 31].

Whereas early in vitro studies demonstrated that the RANKL/RANK/OPG axis plays pivotal roles in regulating diverse physiological processes such as osteoclast formation and function [26, 27], dendritic cell (DC) survival and activation [32–34], and T-cell activation [35, 36], RANKL and RANK knockout models later revealed that the RANKL/RANK/OPG system is also critically involved in lymph node organogenesis [35, 37, 38], B-cell differentiation [35, 37], development of medullary thymic epithelial cells [39, 40]and mammary gland development [41]. Recently, this system has been shown to play a role in thermoregulation in females as well as fever response in inflammation [42].

2.2. The Essential Role of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system in Osteoclast Biology

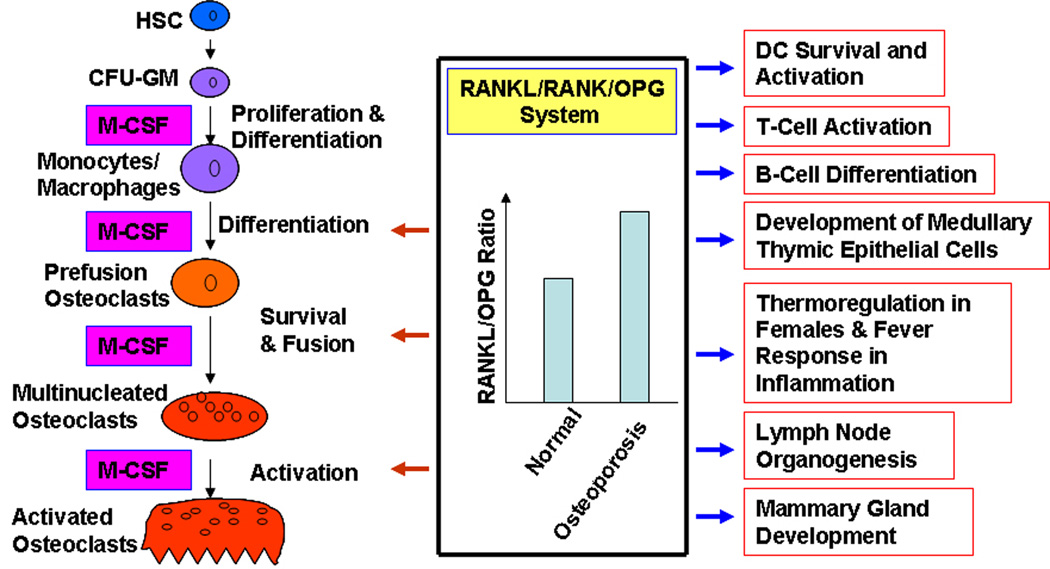

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells that differentiate from mononuclear cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage upon stimulation by two essential factors: RANKL and the monocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) [19, 43]. The key steps of osteoclast differentiation are detailed in Figure 1. Briefly, hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) give rise to colony forming unit-granulocytes/macrophages (CFU-GM), which further differentiate into cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage within the bone marrow. The mononuclear cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage are generally considered to be osteoclast precursors and are attracted to prospective resorption sites by an unknown mechanism (presumably by chemotaxis) where they attach to the bone matrix. Both M-CSF and RANKL are required to promote differentiation of the attached mononuclear precursors into prefusion osteoclasts. M-CSF and RANKL further promote survival and fusion of prefusion cells to become multinucleated mature osteoclasts [19, 44].

Figure 1.

Known Functions of the RANKL/RANK/OPG System. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; CFU-GM, colony-forming unit - granulocyte/macrophage; DC, dendritic cells.

The potential of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system as a promising new therapeutic target for osteoporosis was quickly appreciated shortly after its discovery based on the following observations: 1) Mice lacking the gene for either RANK or RANKL develop osteopetrosis due to a complete failure to form osteoclasts [35, 37, 45]; this indicates that the RANKL/RANK system is essential for osteoclast differentiation (Figure 1). Consistently, mice deficient in OPG develop early onset of osteoporosis due to elevated osteoclast differentiation [30], whereas transgenic mice over-expressing OPG exhibit osteopetrosis resulting from a decrease in late stages of osteoclast differentiation [31]. Moreover, RANKL is also an important modulator of osteoclast function and survival [46–49]. Thus, targeting the RANKL/RANK/OPG system should produce potent effects on osteoclast differentiation and function; 2) It has been shown that RANKL expression is elevated in the bone marrow cells of postmenopausal women [50](Figure 1). Moreover, it has been shown that stromal cells/osteoblasts from aged mice (C57BL/6) express higher levels of RANKL and lower levels of OPG than the cells from young mice [51], and this change in RANKL/OPG expression has been shown to expand the pool of osteoclast precursors [52].

As shown in Figure 1, the RANKL/RANK/OPG axis not only plays a pivotal role in osteoclast formation and function [53], but is also involved in other biological processes such as DC survival and activation [32–34], T-cell activation [35, 36], B-cell differentiation [35, 37], lymph node development [35, 37, 38], development of medullary thymic epithelial cells [39, 40], mammary gland development [41], and thermoregulation in females/fever response in inflammation [42]. It is expected that therapeutics functioning to block RANKL-RANK interaction may not have adverse effects on mammary gland development since this biological process is largely an irrelevant issue in most patients with bone disorders such as postmenopausal women [41]. Moreover, therapeutics targeting the RANKL-RANK interaction is also unlikely to affect lymph node organogenesis since this process is complete in adults [54]. However, use of agents that function to inhibit RANKL-RANK interaction to treat osteoporosis may cause adverse side effects on patient immune responses [55, 56]. Given that RANKL has been recently shown to play a role in thermoregulation in females and fever response during inflammation [42], there is further a concern regarding potential adverse effects on thermoregulation with global blockage of the RANKL-RANK interaction.

2.3. RANK Signaling Pathways as New Therapeutic Targets for Osteoporosis

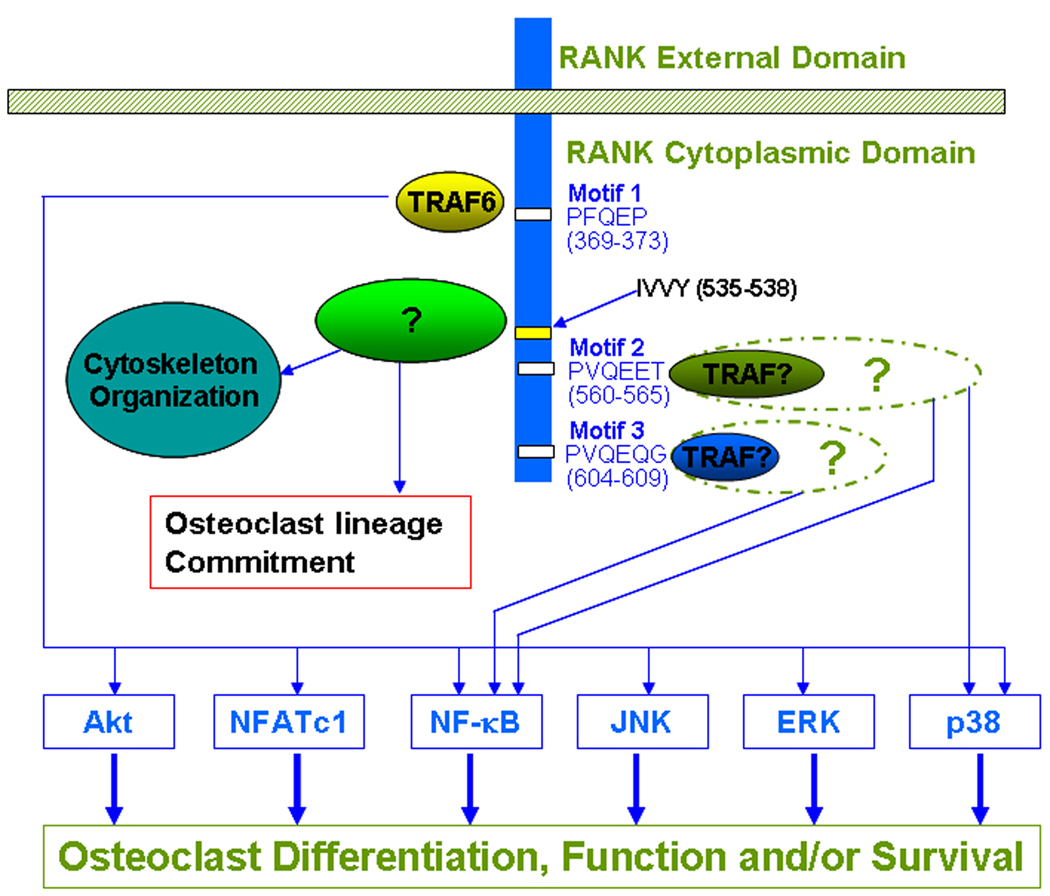

Given concerns about therapeutic targeting of the RANKL-RANK interaction, it is necessary to examine RANK signaling pathways to look for unique targets involved in regulating osteoclast formation, function, and/or survival for specific anti-osteoclast therapy. RANKL and RANK belong to the TNF and TNFR families, respectively [28]. Given that TNFR family members primarily employ TNF receptor associated factors (TRAFs) to transmit downstream signaling [57, 58], most previous studies have been performed to characterize the TRAF-dependent signaling pathways in osteoclasts. These studies have demonstrated using in vitro binding assays and over-expression systems in transformed cells that five TRAF proteins (TRAF 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6) interact with RANK [53, 59–63]. Subsequent functional studies revealed that RANK contains only three functional TRAF-binding motifs: PFQEP369–373 (Motif 1), PVQEET560–565 (Motif 2) and PVQEQG604–609 (Motif 3), which are able to independently mediate osteoclast formation and function [64, 65] (Figure 2). Moreover, Motif 2 and Motif 3 are more potent than Motif 1 in mediating osteoclast formation [65]. Moreover, it has been established that these three functional RANK motifs collectively activate six major signaling pathways (NF-кB, JNK, ERK, p38, NFATc1 and Akt) to regulate osteoclast formation, function and/or survival [19, 66, 67](Figure 2).

Figure 2.

RANK Signaling Pathways in Osteoclast Differentiation, Function and Survival. RANK has three TRAF-binding motifs (Motif 1, Motif 2 and Motif 3), which recruit TRAF proteins to activate six major signaling pathways (Akt, NFATc1, NF-κB, JNK, ERK and p38) which are implicated in osteoclast differentiation, function and/or survival. RANK also contains an IVVY motif which is likely to mediate commitment to the osteoclast lineage by binding a novel signaling protein unrelated to the known TRAFs. It has been also shown that the IVVY motif is involved in cytoskeletal organization in osteoclasts. The sequence and location of these motifs are shown. “?” denotes that the component(s) has not been convincingly identified.

Among the three TRAF binding sites, Motif 1 has been most extensively studied and has been shown to engage TRAF6 to transmit intracellular signaling pathways [68]. Recruitment of TRAF6 to Motif 1 leads to formation of a signaling complex containing c-Src, TAB2, TAK1 and TAB1, which subsequently activates Akt, NF-кB, JNK, p38 and ERK pathways [49, 68–75] (Figure 2). Moreover, the TRAF6-mediated signaling complex is also involved in RANKL-induced activation of NFATc1, which has been shown to be a master regulator of osteoclastogenesis, expression in osteoclast precursors [74] (Figure 2).

Several previous in vitro assays have shown that Motif 2 interacts with TRAF3 while Motif 3 binds TRAF2 or TRAF5 [53, 63], but the functional relevance of TRAF proteins interacting with Motif 2 or Motif 3 have not been functionally validated. In osteoclast precursors, it has been shown that Motif 2 initiates intracellular signaling pathways leading to the activation of NF-кB and p38 pathways while Motif 3 mediates only the activation of the NF-кB pathway [65]. However, the molecular components of the signaling complexes formed upon the recruitment of TRAF proteins at Motif 2 and Motif 3 have not been elucidated.

Largely based on the comparison of the regulatory role of RANKL with that of IL-1 in mediating osteoclastogenesis, it was speculated that RANKL may activate a novel signaling pathway critical for osteoclastogenesis. Specifically, although IL-1R, like RANK, also engages TRAF6, a key downstream signaling molecule that activates most of the signaling pathways known to be activated by RANK such as the NF-κB and MAPK pathways [76, 77], administration of IL-1 to RANK−/− mice fails to induce osteoclastogenesis in vivo [45]. Furthermore, in vitro studies also demonstrated that IL-1 failed to stimulate osteoclastogenesis [78]. These in vivo and in vitro observations suggest that RANK is likely to activate a TRAF6-independent signaling pathway(s) which plays an essential role in osteoclastogenesis. Consistently, a specific 4-a.a. motif (IVVY535–538) in the RANK cytoplasmic domain was identified and shown to play an essential role in osteoclastogenesis by committing macrophages to the osteoclast lineage [79] (Figure 2). Mutation of the IVVY motif does not affect the activation of the known RANK pathways, indicating that this motif employs a novel mechanism to regulate osteoclast lineage commitment. Recently, it has been reported that this motif is also involved in regulating osteoclast function by activating Rac, which in turn mediates cytoskeleton organization [80]. Since Rac has been shown to regulate osteoclastogenesis [81], it is possible that the IVVY-mediated Rac activation may also be involved in osteoclastogenesis. Nonetheless, future studies are needed to address the hypothesis.

2.4. Selective Targeting of Motif 2 (PVQEET560–565) and Motif 3 (PVQEQG604–609) for Osteoporosis

The recent discovery that RANK contains three TRAF-binding motifs that independently mediate osteoclast formation and function has raised the question of whether some of these motifs can be specifically targeted for therapy of bone disorders including osteoporosis [64, 65, 82, 83]. Of the three motifs, however, Motif 2 and Motif 3 are more efficient in stimulating osteoclast formation and function [65, 84]. Notably, the mutation of both Motif 2 and Motif 3 drastically impairs osteoclastogenesis induced by RANKL [65], supporting that these two TRAF-binding motifs can serve as potent therapeutic targets for osteoporosis. Moreover, it has been well established that two proinflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-1 play an important role in the pathogenesis of various bone loss including osteoporosis by stimulating osteoclast formation and function [85, 86]. TNF/IL-1-induced osteoclastogenesis requires priming of BMMs by RANKL [87, 88]. Interestingly, the mutation of Motif 2 and Motif 3 significantly blocked osteoclast formation and function as induced by these two proinflammatory cytokines [89]. These observations together support the promising potential of these two RANK motifs as new therapeutic targets for osteoporosis.

The specificity of Motif 2 and Motif 3 in osteoclast biology has been moderately addressed in vitro. Although the RANKL/RANK system plays crucial roles in immune functions such as DC survival and activation [32–34], T-cell activation [35, 36] and B-cell differentiation [35, 37] (Figure 1), these biological functions are likely to be primarily initiated through Motif 1. For instance, Motif 1 activates intracellular signaling pathways by recruiting TRAF 6, which plays an important role in DC maturation and development [90], T-cell activation [91] and B-cell differentiation [92, 93]. Motif 2 and Motif 3, contrary to Motif 1, do not recruit TRAF 6 and thus should play a minimal role in immune response. As discussed above, agents that act to block the RANKL-RANK interaction are unlikely to affect lymph node organogenesis or mammary gland development. It remains to be determined whether targeting of these TRAF-binding sites will have an impact on thermoregulation and inflammatory fever response. While these observations support that Motif 2-and Motif 3-induced signaling pathways are likely to serve as specific therapeutic targets for osteoporosis, future generation of knock-in mice bearing inactivating mutations in both Motifs 2 and 3 is warranted to further evaluate their potency and specificity as therapeutic targets for osteoporosis. Specifically, the knock-in mice could confirm the specificity of these motifs in osteoclast biology by examining their roles in other biological systems.

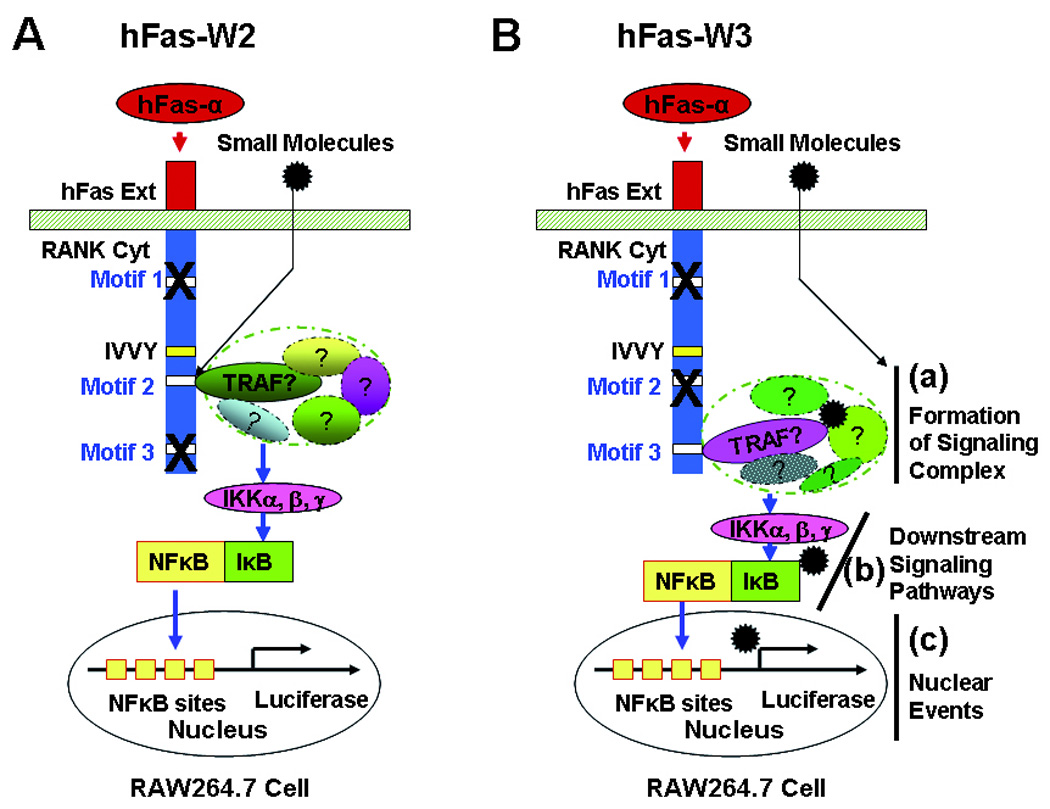

Cell-based assays for identifying small molecules capable of blocking the signaling pathways activated by Motif 2 and Motif 3 have been proposed [83]. The cell-based assay is composed of three principle components [83](Figure 3): the macrophage-like RAW264.7 (RAW) murine line, an NF-κB Luciferase reporter, and a human Fas-mouse RANK chimeric receptor. The RAW cell line was chosen because, as one of the few macrophage-like cell lines that can differentiate into osteoclast-like cells [94, 95], it should retain all signaling capacity required for osteoclastogenesis. The stable NF-κB reporter RAW cell line functions like any other such reporter line in that activation of NF-κB signaling stimulates the expression of firefly Luciferase. This increase in expression can be quantified through the addition of the Luciferase substrate, luciferin, and measurement of subsequent luminescence. The chimeric receptor is the tool that differentiates the cell-based assay from more general NF-κB response assays. Any factor that can activate NF-κB will produce a luminescent signal, but identification of motif-specific inhibitors requires activation of specific RANK intracellular motifs. Because its extracellular domain has been replaced with that of the human Fas receptor, the chimeric RANK’s intracellular signaling is triggered not by RANKL, but by an antibody that specifically activates human (but not mouse) Fas; this specific activation allows interrogation of the signaling of individual intracellular motifs without interference from signaling activated by endogenous RANK [83] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cell-based Assays for Identifying Small Molecules Blocking the TRAF2/3-mediated Pathways. (A) Cell-based assay involving a chimeric receptor named hFas-W2, which consists of the human Fas external domain linked to the mouse RANK transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains containing inactivating mutations in all TRAF motifs except Motif 2. (B) Cell-based assay involving a chimeric receptor named hFas-W3, which consists of the human Fas external domain linked to the mouse RANK transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains containing inactivating mutations in all TRAF motifs except Motif 3. hFas-α, anti-human Fas antibody; hFas Ext, human Fas external domain; RANK Cyt, RANK cytoplasmic domain. “?” denotes that the component(s) has not been convincingly identified.

For the purposes of this particular assay, two different chimeric receptors are needed: hFas-W2 (Figure 3A), in which the signaling of all functional motifs except Motif 2 is attenuated via point mutations within the motif sequences, and hFas-W3 (Figure 3B), which is similar to hFas-W2 except it is Motif 3 that retains its full signaling capacity. These two mutant receptors allow assessment of effects of various compounds on the signaling of either motif, and, since both motifs ultimately activate NF-κB, they can be applied to the NF-κB reporter RAW cell line and assessed following identical protocols. As an example, an NF-κB reporter RAW cell line that expresses hFas-W2 will respond to a treatment with the human Fas activating antibody by initiating full signaling through only Motif 2 with the ultimate downstream consequence of NF-κB translocation to the nucleus, which can then be measured by a standardized luminescent assay (Figure 3A). Any compound treatment that can inhibit Motif 2 signaling upstream of NF-κB will cause a reduction in luminescence as compared to mock treated controls. Any compounds found to inhibit the signaling of Motif 2 and/or 3 can then be tested against another chimeric receptor construct, hFas-P23, in which signaling from all motifs except Motif 2 and 3 is intact. The purpose of this follow-up assay is to determine whether the compound is able to specifically inhibit Motif 2 or 3 – if the compound is found to cause a reduction in luminescence induced by hFas-P23, the interpretation would be that the compound is not specific to Motif 2 and/or 3 as it can inhibit the signaling of other RANK intracellular motifs and should be rejected from future functional assessments.

These assays will identify small molecules which can interfere with any step of the signaling pathway leading to the activation of the reporter gene, including compounds capable of blocking the interaction between Motif 2/3 and TRAF proteins as shown in Figure 3A and those that target subsequent signaling cascades such as a) the formation of signaling complexes, b) downstream signaling pathways and c) the nuclear events as highlighted in Figure 3B. Among these different signaling events, the Motif-TRAF interaction probably represents the best targeting choice for the following reasons: 1) the RANK cytoplasmic motifs are not only more accessible to prospective small molecules since a compound only needs to cross the cell membrane to block the interaction between Motif 2/3 and TRAF proteins without needing to overcome potential barriers such as cytoskeletal networks and/or other intracellular organelles and 2) the disruption of the interaction is more likely to give rise to specificity compared to targeting the further downstream steps shown in Figure 3B. While the precise components of the signaling complexes assembled at Motif 2 and Motif 3 have not been identified, it is possible that these complexes share many common proteins with that at Motif 1/TRAF6 [96] and those used by other TNFR family members. Thus, compounds capable of preventing/disrupting the formation of the signaling compounds may also affect the signaling activated by Motif 1 and other TNFR family members in osteoclast precursors as well as other cell types. Similarly, the downstream signaling pathway (b, Figure 3B) and nuclear events (c, Figure 3B) may also be shared by other members of the TNFR family to regulate distinct biological functions in a variety of cell types. This raises a concern regarding potential adverse effects of targeting these steps on other biological systems. As a result, it is important to functionally identify and characterize the TRAF proteins binding to these two RANK motifs. In particular, identification of the specific domains within the TRAF proteins mediating the interaction with Motif 2 and Motif 3 will allow development of additional assays such as biochemical or fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assays to expedite developments of new drugs with higher specificity and efficacy for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis.

2.5. The Potential of the RANK IVVY535–538 Motif to Serve as an Effective and Specific Therapeutic Target for Osteoporosis

The RANK IVVY motif represents another important drug target for osteoporosis (Figure 2), and targeting this RANK motif, due to its indispensable role in osteoclastogenesis, may provide even greater efficacy [79, 80]. The IVVY motif plays an essential role in osteoclastogenesis by committing BMMs to the osteoclast lineage [79]. Moreover, the IVVY motif, similarly to Motif 2 and Motif 3, has also been shown to play a central role in the TNF- and IL-1-mediated osteoclastogenesis as its mutational inactivation fully inhibits osteoclastogenesis in response to these two factors in vitro [97]. It has been recently shown that a peptide-mimetic inhibitor of this novel RANK motif was able to significantly inhibit osteoclastogenesis in vitro and in a murine ovariectomy-induced bone loss model [80]. Taken together, these findings support the effectiveness of this RANK motif as a potent therapeutic target for osteoporosis.

Mutational inactivation of this RANK motif completely blocked osteoclastogenesis in vitro without impacting the known osteoclastogenic signaling pathways [79], suggesting that this motif activates a unique pathway and thus has the potential to serve as a specific therapeutic target. However, whether this motif plays a role in other biological systems remains unclear. Hence, future generation of knock-in mice bearing inactivating mutations in this RANK IVVY motif will be able to address its role in osteoclastogenesis in vivo but, more importantly, the knock-in model can also be used to determine whether this motif is involved in regulating other RANKL/RANK-mediated cellular functions or biological processes as shown in Figure 1.

The next critical issue regarding targeting this RANK motif is how to identify small molecules that block its function. This endeavor undoubtedly requires a better understanding of the signaling pathway initiated by this motif. Given that mutation of the RANK IVVY motif does not affect the ability of RANK to activate the various known RANK signaling pathways [79], it is likely that this motif exerts its effect on osteoclast lineage commitment by binding an unidentified signaling molecule rather than by establishing or maintaining the functional 3-dimensional structure of the RANK cytoplasmic domain. Thus, the next key step in elucidating the IVVY motif-mediated signaling pathway is to identify the signaling protein recruited by the IVVY motif. Interestingly, two proteins (Vav3 and Gab2) have been shown to be able to interact with the IVVY motif [80] [98]. Future independent validation of the interacting candidate proteins and further elucidation of specific interaction domains within the protein(s) will greatly facilitate development of in vitro screens such as biochemical or FRET-based assays with which compounds capable of blocking the function of this unique RANK motif can be identified.

It is evident that Motif 2, Motif 3 and the IVVY motif represent new therapeutic targets for osteoporosis treatment. However, which of these RANK motifs will emerge as the preferred choice(s) remains to be defined. It is expected that the RANK IVVY motif may represent the best option since the previous in vitro studies have demonstrated that mutational inactivation of this motif alone completely blocked osteoclastogenesis [79]. In contrast, significant inhibition of osteoclast formation and function required the mutation of both Motif 2 and Motif 3 [65]. Nevertheless, since osteoporosis is a heterogeneous disease, Motif 2 and Motif 3 may be preferable therapeutic target for certain types of osteoporosis. Nevertheless, it is important to consider all RANK cytoplasmic motifs as potential targets at this early stage of target validation.

3. Conclusion

In summary, given the crucial role of RANKL in osteoclast formation and function, the RANKL/RANK/OPG regulatory axis represents one of the most promising new therapeutic targets for osteoporosis. The successful development of a high affinity anti-RANKL antibody (denosumab) by Amgen Inc [23–25], which holds a great potential to become a new antiresorptive drug for treating osteoporosis, further supports the notion that the RANKL/RANK/OPG axis can serve as a therapeutic target for various bone disorders. Nonetheless, since RANKL has been shown to regulate a number of other biological processes including the immune response, it has been a concern that therapeutic strategies involving blockade of the RANKL-RANK interaction may cause some side-effects. An analysis of the clinical trial data on denosumab has revealed an increased risk of serious infections in patients treated with denosumab [55, 56], which heightens not only the concern but also a need to search for better strategies to target the RANKL/RANK/OPG regulatory axis for osteoporosis therapy. The intense investigation of RANKL signaling in osteoclast biology over the last decade has identified two TRAF-binding motifs (PVQEET560–565 and PVQEQG604–609) and a TRAF-independent motif (IVVY535–538) in the cytoplasmic domain of RANK which have the potential to serve as potent and specific therapeutic targets for osteoporosis therapy. Future studies involving animal models are needed to further address the potency and specificity of these motifs as therapeutic targets. Moreover, future elucidation of the signaling pathways activated by these motifs can facilitate the development of experimental strategies to identify compounds against these targets.

4. Expert Opinion

With over 2 million fractures attributable to osteoporosis per year in the US alone, this disease is and will continue to present public health challenges as the population ages [99]. At present, however, we still lack efficacious and safe drugs for this prevalent bone disorder. For instance, the available anti-resorptive drugs are able to reduce vertebral fractures ranging from 44% to 75% in patents with no preexisting fractures, and from 30% to 47% in patients with preexisting fractures [15–18, 100–103]. Hence, there will remain nearly a million osteoporotic factures per year even with widespread adoption of these treatments. In the absence of new therapeutics, this number can only rise. In response to this need, great strides have been made in both academia and industry towards new drugs and new methods of calculating fracture risk, and these accomplishments can and must be expanded upon.

As with most traumatic medical events, the best approach for dealing with fractures from not only a cost and public health standpoint but also in terms of individual well-being is prevention. Of course, the ideal bone-protecting factor would be safe enough to put in the drinking water as fluoride was done to prevent tooth decay. Osteoporotic fractures, however, are not a cross-sectional problem like tooth decay; only a segment of the population would benefit from such a drastic intervention. While antiresorptives in the water supply is not tenable, safety in antiresorptives is a worthy goal. Safety is one of the three pillars of an ideal drug. The other two components are efficacy and cost. Efficacy and safety need little explanation – clearly an ideal drug will target excessive bone resorption without causing side-effects. Cost, however, is a more problematic issue. Denosumab, which stands poised to enter the market, has shown tremendous promise in effectively reducing osteoclast function with few overt side-effects. This antibody may, indeed, achieve desired reductions in bone resorption for many patients, but, as an antibody, the lifelong cost of regular treatments will be prohibitively expensive for a large section of the population. For this reason, the search for safe, effective, and inexpensive antiresorptive drugs must continue. Nonetheless, there may be a limit to what antiresorptive therapy can deliver for osteoporosis. Thus, antiresorptive drugs may be used in combination of anabolic agents (bone-building) to further improve efficacy.

Ultimately, patients may find themselves in a situation analogous to the jocular restaurant patron who is offered fast, good, and cheap food but is only permitted to choose two of the three aspects. This should not deter research efforts. With growing knowledge of RANK signaling, the medical research community stands on the verge of finding perhaps not the ideal antiresorptive, but certainly new options from which patients can choose to prevent osteoporosis and manage existing cases. Over a decade of research into the RANKL/RANK/OPG system has provided the tools; all that remains is the will to move forward.

Article Highlights Box.

While osteoporosis has become a worldwide health and social issue due to an aging population, we still lack efficacious and safe drugs for this disease

The RANKL/RANK/OPG system was discovered in the late 1990s and has been shown to play an important role in osteoclast formation/function as well as a number of other biological processes

Although the RANKL/RANK/OPG System represents one of the most promising new therapeutic targets for Osteoporosis, therapeutic blocking of RANKL-RANK interaction may have adverse effects on immune response

Selective targeting of RANK signaling pathways has the potential to improve efficacy and achieve specificity

Two TRAF-binding motifs (PVQEET560–565 and PVQEQG604–609) in the cytoplasmic domain of RANK have the potential to serve as potent and specific therapeutic targets for Osteoporosis

A TRAF-independent RANK cytoplasmic motif (IVVY535–538) represents another effective and specific therapeutic target for osteoporosis

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMMs

bone marrow macrophages

- CFU-GM

colony forming unit-granulocytes/macrophage

- DC

dendritic cell

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cells

- IL-1

interleukin 1

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- M-CSF

monocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- NFATc1

nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- ODF

osteoclast differentiation factor

- OPG

osteoprotegerin

- OPGL

OPG ligand

- RANK

receptor activator of NF-κB

- RANKL

RANK ligand

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TNFR

TNF receptor

- TRAF

TNFR-associated factor

- TRANCE

TNF-related activation-induced cytokine

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

X Feng has received grants from the NIH and the American College of Rheumatology. J Jules and J Ashley have received fellowships from the NIH.

Contributor Information

Joel Jules, Graduate Students, Molecular and Cellular Pathology Graduate Program, Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA.

Jason W. Ashley, Graduate Students, Molecular and Cellular Pathology Graduate Program, Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA

Xu Feng, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA.

References

- 1.NIH Consensus Development Panel. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–795. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcus R, Bouxsein M. The nature of osteoporosis. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Nelson DA, et al., editors. Osteoporosis. Third Edition ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riggs BL, Wahner HW, Seeman E, et al. Changes in bone mineral density of the proximal femur and spine with aging. Differences between the postmenopausal and senile osteoporosis syndromes. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:716–723. doi: 10.1172/JCI110667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ. The type I/type II model for involutional osteoporosis. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kesley J, et al., editors. Osteoporosis. Second Edition ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. [Review] [126 refs] Nature Reviews Genetics. 2003;4:638–649. doi: 10.1038/nrg1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol. 2007;170:427–435. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3318–3325. doi: 10.1172/JCI27071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts; culprits in inflammatory osteolysis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2006;8:1–8. doi: 10.1186/ar1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldring SR. Pathogenesis of bone and cartilage destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. [Review] [48 refs] Rheumatology. 2003;42 Suppl 2:ii11–ii16. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mundy GR. Metastasis to bone: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. [Review] [76 refs] Nature Reviews. 2002;2:584–593. doi: 10.1038/nrc867. Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefanick ML. Estrogens and progestins: background and history, trends in use, and guidelines and regimens approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Am J Med. 2005;118 Suppl 12B:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prince R, Muchmore DB, Siris ES. Estrogen analogues: selective estrogen receptor modulators and phytoestrogens. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Nelson DA, et al., editors. Osteoporosis. 3rd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 1705–1723. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller P. Bisphosphonates: pharmacology and use in the treatment of osteoporosis. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Nelson DA, et al., editors. Osteoporosis. 3rd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 1725–1742. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruber HE, Ivey JL, Baylink DJ, et al. Long-term calcitonin therapy in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Metabolism. 1984;33:295–303. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller PD, Derman RJ. What is the best balance of benefits and risks among anti-resorptive therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis? Osteoporos Int. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1208-3. * An updated and concise review on the efficacy and safety of current antiresorptive drugs on market

- 16.Stepan JJ, Alenfeld F, Boivin G, et al. Mechanisms of action of antiresorptive therapies of postmenopausal osteoporosis [Review] [59 refs] Source Endocrine Regulations. 2003 Dec;37(4):225–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lufkin EG, Sarkar S, Kulkarni PM, et al. Antiresorptive treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: review of randomized clinical studies and rationale for the Evista alendronate comparison (EVA) trial. [Review] [48 refs] Current Medical Research & Opinion. 2004;20:351–357. doi: 10.1185/030079904125003071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcus R, Wong M, Heath H, III, et al. Antiresorptive treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: comparison of study designs and outcomes in large clinical trials with fracture as an endpoint [Review] [149 refs] Endocr Revs. 2002;23:16–37. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. [Review] [77 refs] Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. ** This paper provides a comprehensive review of osteoclast biology with a focus on the role of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system in osteoclast differentiation and function

- 20.Wittrant Y, Theoleyre S, Chipoy C, et al. RANKL/RANK/OPG: new therapeutic targets in bone tumours and associated osteolysis. [Review] [67 refs] Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1704:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClung MR, Lewiecki EM, Cohen SB, et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:821–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044459. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClung MR. Inhibition of RANKL as a treatment for osteoporosis: preclinical and early clinical studies. [Review] [47 refs] Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2006;4:28–33. doi: 10.1007/s11914-006-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewiecki EM. Current and emerging pharmacologic therapies for the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1615–1626. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller PD. Denosumab: anti-RANKL antibody. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009;7:18–22. doi: 10.1007/s11914-009-0004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756–765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. ** This paper reports the results of a recent large clinical trial on denosumab

- 26. Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. * The original paper on the discovery of RANKL and its role in osteoclast differentiation and function

- 27.Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anderson DM, Maraskovsky E, Billingsley WL, et al. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature. 1997;390:175–179. doi: 10.1038/36593. * The original paper on the discovery of RANK and its role in T-cell and dendritic cells

- 29.Wong BR, Rho J, Arron J, et al. TRANCE is a novel ligand of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family that activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase in T cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25190–25194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, et al. osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1260–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong BR, Josien R, Lee SY, et al. TRANCE (tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-related activation-induced cytokine), a new TNF family member predominantly expressed in T cells, is a dendritic cell-specific survival factor. J Exp Med. 1997;186:2075–2080. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Josien R, Wong BR, Li HL, et al. TRANCE, a TNF family member, is differentially expressed on T cell subsets and induces cytokine production in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:2562–2568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Josien R, Li HL, Ingulli E, et al. TRANCE, a tumor necrosis factor family member, enhances the longevity and adjuvant properties of dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;191:495–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, et al. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397:315–323. doi: 10.1038/16852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bachmann MF, Wong BR, Josien R, et al. TRANCE, a tumor necrosis factor family member critical for CD40 ligand-independent T helper cell activation. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1025–1031. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dougall WC, Glaccum M, Charrier K, et al. RANK is essential for osteoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2412–2424. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim D, Mebius RE, MacMicking JD, et al. Regulation of peripheral lymph node genesis by the tumor necrosis factor family member TRANCE. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1467–1478. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akiyama T, Shimo Y, Yanai H, et al. The tumor necrosis factor family receptors RANK and CD40 cooperatively establish the thymic medullary microenvironment and self-tolerance. Immunity. 2008;29:423–437. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hikosaka Y, Nitta T, Ohigashi I, et al. The cytokine RANKL produced by positively selected thymocytes fosters medullary thymic epithelial cells that express autoimmune regulator. Immunity. 2008;29:438–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fata JE, Kong YY, Li J, et al. The osteoclast differentiation factor osteoprotegerin-ligand is essential for mammary gland development. Cell. 2000;103:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanada R, Leibbrandt A, Hanada T, et al. Central control of fever and female body temperature by RANKL/RANK. Nature. 2009;462:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature08596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suda T, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, et al. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocr Revs. 1999;20:345–357. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclast Biology. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J, editors. Osteoporosis. 2nd Edition ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 73–106. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Sarosi I, Yan X-Q, et al. RANK is the intrinsic hematopoietic cell surface receptor that controls osteoclastogenesis and regulation of bone mass and calcium metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1566–1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burgess TL, Qian Y, Kaufman S, et al. The ligand for osteoprotegerin (OPGL) directly activates mature osteoclasts. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:527–538. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuller K, Wong B, Fox S, et al. TRANCE is necessary and sufficient for osteoblast-mediated activation of bone resorption in osteoclasts. J Exp Med. 1998;188:997–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lum L, Wong BR, Josien R, et al. Evidence for a role of a tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha)-converting enzyme-like protease in shedding of TRANCE, a TNF family member involved in osteoclastogenesis and dendritic cell survival. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13613–13618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong BR, Besser D, Kim N, et al. TRANCE, a TNF family member, activates Akt/PKB through a signaling complex involving TRAF6 and c-Src. Molecular Cell. 1999;4:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eghbali-Fatourechi G, Khosla S, Sanyal A, et al. Role of RANK ligand in mediating increased bone resorption in early postmenopausal women. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1221–1230. doi: 10.1172/JCI17215. [see comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao J, Venton L, Sakata T, et al. Expression of RANKL and OPG correlates with age-related bone loss in male C57BL/6 mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:270–277. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao JJ, Wronski TJ, Iwaniec U, et al. Aging increases stromal/osteoblastic cell-induced osteoclastogenesis and alters the osteoclast precursor pool in the mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1659–1668. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsu H, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor family member RANK mediates osteoclast differentiation and activation induced by osteoprotegerin ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3540–3545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoorweg K, Cupedo T. Development of human lymph nodes and Peyer's patches. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Anastasilakis AD, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, et al. Efficacy and safety of denosumab in postmenopausal women with osteopenia or osteoporosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41:721–729. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224109. ** This paper reports the potential side effect of denosumab on the immune function based on the analysis of the clinical trial data reported in Ref 26

- 56.Toulis KA, Anastasilakis AD. Erratum to: Increased risk of serious infections in women with osteopenia or osteoporosis treated with denosumab. Osteoporos Int. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. [Review] [115 refs] Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Tschopp J. The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. [Review] [53 refs] Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2002;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darnay BG, Haridas V, Ni J, et al. Interaction with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors and activation of NF-kappab and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20551–20555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong BR, Josien R, Lee SY, et al. The TRAF family of signal transducers mediates NF-KAPPA-B activation by the TRANCE receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28355–28359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim HH, Lee DE, Shin JN, et al. Receptor activator of NF-kappaB recruits multiple TRAF family adaptors and activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase. FEBS Letters. 1999;443:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Darnay BG, Ni J, Moore PA, et al. Activation of NF-kappaB by RANK requires tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 6 and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. Identification of a novel TRAF6 interaction motif. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7724–7731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galibert L, Tometsko ME, Anderson DM, et al. The involvement of multiple tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factors in the signaling mechanisms of receptor activator of NF-kappaB, a member of the TNFR superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34120–34127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Armstrong AP, Tometsko ME, Glaccum M, et al. A RANK/TRAF6-dependent signal transduction pathway is essential for osteoclast cytoskeletal organization and resorptive function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44347–44356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202009200. * This paper reports the identifiation of functional RANK motifs involved in regulaing osteoclast formation and fucntion

- 65. Liu W, Xu D, Yang H, et al. Functional identification of three RANK cytoplasmic motifs mediating osteoclast differentiation and function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54759–54769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404687200. * Another study on the identifiation of functional RANK motifs involved in regulaing osteoclast formation and fucntion

- 66.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Matsuo K, et al. RANKL maintains bone homeostasis through c-Fos-dependent induction of interferon-beta.[see comment] Nature. 2002;416:744–749. doi: 10.1038/416744a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feng X. Regulatory roles and molecular signaling of TNF family members in osteoclasts. [Review] [133 refs] Gene. 2005;350:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye H, Arron JR, Lamothe B, et al. Distinct molecular mechanism for initiating TRAF6 signalling. Nature. 2002;418:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature00888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mizukami J, Takaesu G, Akatsuka H, et al. Receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) activates TAK1 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase through a signaling complex containing RANK, TAB2, and TRAF6. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:992–1000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.992-1000.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, et al. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-I kappaB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;398:252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shirakabe K, Yamaguchi K, Shibuya H, et al. TAK1 mediates the ceramide signaling to stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8141–8144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee SW, Han SI, Kim HH, et al. TAK1-dependent activation of AP-1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase by receptor activator of NF-kappaB. Journal of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 2002;35:371–376. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ge B, Gram H, Di Padova F, et al. MAPKK-independent activation of p38alpha mediated by TAB1-dependent autophosphorylation of p38alpha. Science. 2002;295:1291–1294. doi: 10.1126/science.1067289. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Koga T, et al. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Developmental Cell. 2002;3:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ishida N, Hayashi K, Hoshijima M, et al. Large scale gene expression analysis of osteoclastogenesis in vitro and elucidation of NFAT2 as a key regulator. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41147–41156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu H, Arron JR. TRAF6, a molecular bridge spanning adaptive immunity, innate immunity and osteoimmunology. BioEssays. 2003;25:1096–1105. doi: 10.1002/bies.10352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Walsh MC, Kim GK, Maurizio PL, et al. TRAF6 autoubiquitination-independent activation of the NFkappaB and MAPK pathways in response to IL-1 and RANKL. PLoS One. 2008;3:e4064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Azuma Y, Kaji K, Katogi R, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces differentiation of and bone resorption by osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4858–4864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Xu D, Wang S, Liu W, et al. A novel RANK cytoplasmic motif plays an essential role in osteoclastogenesis by committing macrophages to the osteoclast lineage. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4678–4690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510383200. * This paper reports the work on the identifiation of the TRAF-independent motif (IVVY motf) involved in regulaing osteoclast formation

- 80. Kim H, Choi HK, Shin JH, et al. Selective inhibition of RANK blocks osteoclast maturation and function and prevents bone loss in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:813–825. doi: 10.1172/JCI36809. * This paper reports that the IVVY motf plays a crtical role in regulaing osteoclast formation in animal models

- 81.Wang Y, Lebowitz D, Sun C, et al. Identifying the relative contributions of Rac1 and Rac2 to osteoclastogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:260–270. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Feng X. RANK signaling pathways as potent and specific therapeutic targets for bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Future Rheumatology. 2006;1:567–578. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen T, Feng X. Cell-based assay strategy for identification of motif-specific RANK signaling pathway inhibitors. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2006;4:473–482. doi: 10.1089/adt.2006.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu W, Wang S, Wei S, et al. RANK cytoplasmic motif, PFQEP369–373, plays a predominant role in osteoclast survival in part by activating Akt/PKB and its downstream effector AFX/FOXO4. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43064–43072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pacifici R. Cytokines, estrogen, and postmenopausal osteoporosis - the second decade. Endocrinol. 1998;139:2659–2661. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jilka RL. Cytokines, bone remodeling, and estrogen deficiency - a 1998 update. Bone. 1998;23:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lam J, Takeshita S, Barker JE, et al. TNF-alpha induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1481–1488. doi: 10.1172/JCI11176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim JH, Jin HM, Kim K, et al. The mechanism of osteoclast differentiation induced by IL-1. J Immunol. 2009;183:1862–1870. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jules J, Shi Z, Feng X. Three RANK cytoplasmic motifs, IVVY535–538, PVQEET559–564, and PVQEQG604–609, play a critical role in TNF/IL-1-mediated osteoclastogenesis. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 2008;23 Supplement:S34. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kobayashi T, Walsh PT, Walsh MC, et al. TRAF6 is a critical factor for dendritic cell maturation and development. Immunity. 2003;19:353–363. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sun L, Deng L, Ea CK, et al. The TRAF6 ubiquitin ligase and TAK1 kinase mediate IKK activation by BCL10 and MALT1 in T lymphocytes. Mol Cell. 2004;14:289–301. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Qin J, Konno H, Ohshima D, et al. Developmental stage-dependent collaboration between the TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and lymphotoxin pathways for B cell follicle organization in secondary lymphoid organs. J Immunol. 2007;179:6799–6807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kobayashi T, Kim TS, Jacob A, et al. TRAF6 is required for generation of the B-1a B cell compartment as well as T cell-dependent and -independent humoral immune responses. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shui C, Riggs BL, Khosla S. The immunosuppressant rapamycin, alone or with transforming growth factor-beta, enhances osteoclast differentiation of RAW264.7 monocyte-macrophage cells in the presence of RANK-ligand. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;71:437–446. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Battaglino R, Kim D, Fu B, et al. c-Myc is required for osteoclast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:763–773. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Feng X. RANKing intracelluar cellular signaling in osteoclasts. IUBMB Life. 2005;57:389–395. doi: 10.1080/15216540500137669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jules J, Shi Z, Liu W, et al. The RANKL cytoplasmic motif, IVVY535–538, plays an essential role in TNF-á- and LI-1-induced osteoclastogenesis. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 2007;22 Supplement:S96. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Taguchi Y, Gohda J, Koga T, et al. A unique domain in RANK is required for Gab2 and PLCgamma2 binding to establish osteoclastogenic signals. Genes Cells. 2009;14:1331–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1998;280:2077–2082. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chesnut CH, III, Silverman S, Andriano K, et al. A randomized trial of nasal spray salmon calcitonin in postmenopausal women with established osteoporosis: the prevent recurrence of osteoporotic fractures study. PROOF Study Group. Am J Med. 2000;109:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Heaney RP, Zizic TM, Fogelman I, et al. Risedronate reduces the risk of first vertebral fracture in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:501–505. doi: 10.1007/s001980200061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]