Abstract

Background

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a common liver disease associated with obesity and diabetes. NASH is a progressive disorder that can lead to cirrhosis and liver failure. Insulin resistance and oxidative stress are thought to play important roles in its pathogenesis. There is no definitive treatment for NASH.

Objectives

PIVENS is conducted to test the hypotheses that treatment with pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione insulin sensitizer, or vitamin E, a naturally available antioxidant, will lead to improvement in hepatic histology in nondiabetic adults with biopsy proven NASH.

Design

PIVENS is a randomized, multicenter, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate whether 96 weeks of treatment with pioglitazone or vitamin E improves hepatic histology in nondiabetic adults with NASH compared to treatment with placebo. Before and post-treatment liver biopsies are read centrally in a masked fashion for an assessment of steatohepatitis and a NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) consisting of steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning. The primary outcome measure is defined as either an improvement in NAS by 2 or more in at least two NAS features, or a post-treatment NAS of 3 or less, and improvement in hepatocyte ballooning by 1 or more, and no worsening of fibrosis.

Methods

PIVENS enrollment started in January 2005 and ended in January 2007 with 247 patients randomized to receive either pioglitazone (30 mg q.d.), vitamin E (800 IU q.d.), or placebo for 96 weeks. Participants will be followed for an additional 24 weeks after stopping the treatment. The study protocol incorporates the use of several validated questionnaires and specimen banking. This protocol was approved by all participating center Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) which was established for monitoring the accumulated interim data as the trial progresses to ensure patient safety and to review efficacy as well as the quality of data collection and overall study management.

Keywords: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, pioglitazone, thiazolidinedione, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ), vitamin E, RRR-α-tocopherol, randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common condition that histologically resembles alcoholic liver disease but occurs in individuals without excessive alcohol consumption [1–4]. Obesity and type 2 diabetes are the two most common risk factors for NAFLD [4]. Due to the ongoing epidemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes, the incidence of NAFLD is increasing significantly both in children and adults [5–7]. NAFLD is broadly categorized as either simple steatosis (nonalcoholic fatty liver: NAFL) or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [3]. NASH is characterized histologically by the presence of steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, Mallory’s hyaline, scattered inflammation and fibrosis [1,3]. Several studies have shown that simple steatosis and NASH have distinct outcomes: simple steatosis is largely benign and has a minimal risk of cirrhosis, whereas NASH is a progressive liver disorder which can lead to cirrhosis and liver failure in a substantial proportion of patients [2,3,8–13]. Several agents have been found to be promising as therapy of NASH in small clinical trials, but none have been proven to alter its natural history or outcome, and none are approved for general use in this disorder.

Although the pathogenesis of NASH is not well understood, it is believed to be caused by two processes or “hits,” one that causes hepatic steatosis and a second one that causes hepatocellular injury and inflammation which then can lead to fibrosis [14,15]. Steatosis induced by obesity or metabolic syndrome is believed to represent the “first hit,” and overlapping mechanisms such as insulin resistance [15–20], oxidative stress [17,21–23] and abnormal cytokine [24,25] production have been proposed as the “second hits.” Insulin resistance is nearly universal in NASH and is thought to play an important role in its pathogenesis by promoting peripheral lipolysis and de novo lipogenesis. Several recent pilot studies have shown encouraging results using the insulin sensitizing thiazolidinediones (TZD) to treat NASH in nondiabetic individuals [26–29]. These studies enrolled small number of patients and all but one were not placebo-controlled. Furthermore, none of these studies had adequate power or duration of follow-up to assess the long term safety of TZDs in this patient population. Other pilot studies have shown that vitamin E, a naturally occurring antioxidant, improves serum biochemical tests in patients with NASH; but definitive studies evaluating its effect on hepatic histology are lacking [30–33].

The Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) was established by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) in 2002 to assess the natural history, pathogenesis and therapy of this disease in both adult and pediatric populations [34]. As part of these broad objectives, the NASH CRN was also charged with development and validation of a histological scoring system that encompasses the spectrum of NAFLD and that allows for assessment of changes with therapy [35].

To assess whether TZDs and vitamin E are efficacious in NASH, the NASH CRN developed a multicenter, double-masked, placebo-controlled study entitled “Pioglitazone versus Vitamin E versus Placebo for the Treatment of Nondiabetic Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (PIVENS).” PIVENS is being conducted by the 8 Clinical Centers and a central Data Coordinating Center of the NASH CRN (see acknowledgments for roster). Pioglitazone, one of the two TZDs commercially available in the United States, is being used as the insulin sensitizer, and RRR-α-tocopherol is the vitamin E formulation used. The NIDDK appointed Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed and approved the study protocol and an Investigational New Drug application (IND) has been obtained by the NIDDK on behalf of the NASH CRN from the Food and Drug Administration. This manuscript describes the design of the PIVENS trial.

2. Methods

Design overview

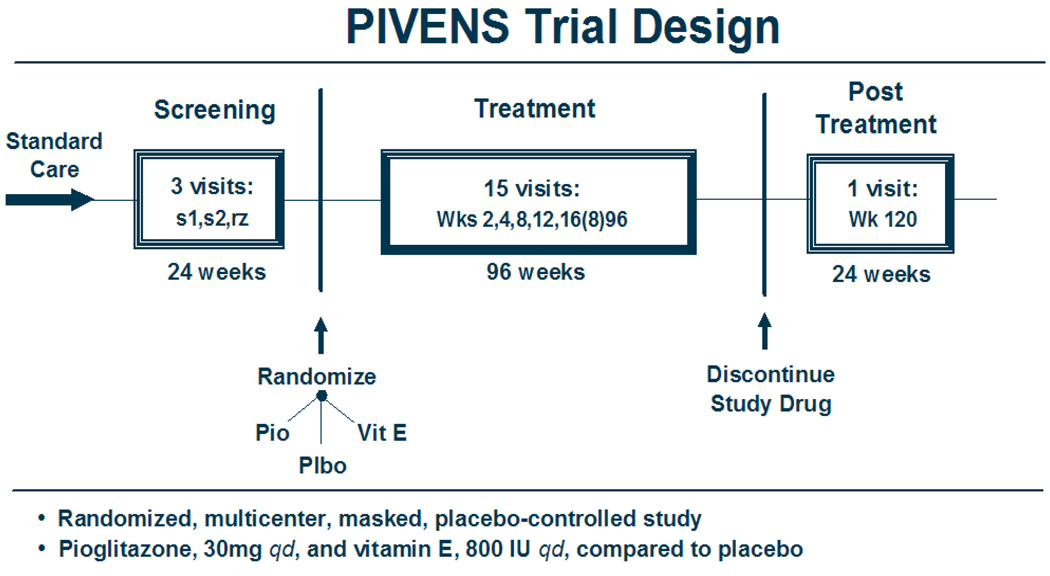

PIVENS is a multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-masked, double-dummy clinical trial of treatment with pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nondiabetic adults with histologically documented NASH. The screening period for evaluating eligibility and collecting baseline data lasted up to 24 weeks before randomization. Eligible patients were randomized to receive either pioglitazone (30 mg q.d.), vitamin E (800 IU q.d.), or placebo for 96 weeks. A 24 week washout period at the end of the treatment phase is planned. The primary comparisons will be made using an intention-to-treat analysis of the change in NAFLD Activity Score (NAS), as determined from standardized histologic scoring of liver biopsies taken at baseline and at week 96. A schematic of the trial design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design schematic

The histological scoring system for NAFLD was developed by the pathology committee as a first step in designing the PIVENS trial so that efficacy could be reproducibly evaluated after 96 weeks of treatment [35]. A semi-quantitative scoring system is applied to the major histological features of NAFLD separating features of active injury that are potentially reversible in the short term including steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning and features that may not be reversible or change only with prolonged therapy such as fibrosis.

Treatment groups

Patients who signed an informed consent statement and who met the eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to one of three groups for 96 weeks of treatment:

Group 1: Pioglitazone (30 mg q.d.) and vitamin E-placebo (q.d)

Group 2: Vitamin E (800 IU, natural form, q.d.) and pioglitazone-placebo (q.d.)

Group 3: Pioglitazone-placebo (q.d.) and vitamin E-placebo (q.d.)

Pioglitazone (Actos®, Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc., Deerfield, IL) is administered as a single tablet of 30 mg per day orally with the morning meal. A similar appearing placebo tablet is taken daily by participants assigned to either the placebo group or the vitamin E group. The rationale for choosing this dosage was based upon earlier pilot studies that examined the safety and efficacy of pioglitazone in patients with NASH [27–29].

The formulation of vitamin E (Nature Made®, Pharmavite, LLC, Mission Hills, CA) used in this study is the natural form of vitamin E (RRR-α-tocopherol, formerly known as d-α-tocopherol) at a daily dosage of 800 IU administered orally via a single softgel. A similar appearing placebo softgel is taken daily by participants assigned to either the pioglitazone group or the placebo group. Double-masked trials and large population studies have shown that oral vitamin E at 800 IU daily dose is safe with no significant side effects [36,37]. The vitamin E dose chosen for this trial (800 IU q.d.) is within the range of vitamin E dosage that has been tested for the treatment of NASH in previous pilot studies [30–33]. As there is no proven pharmacologic therapy for NASH, using a placebo for comparative purposes is justified.

In addition to study medications, participants receive standardized recommendations concerning life-style modification (dietary modification, weight loss, exercise), use of prescription or non-prescription medicines or herbal remedies or dietary supplements, consumption of alcohol, and management of various co-morbid illnesses. Per PIVENS protocol, participants are not allowed any prescription or over-the-counter medication or herbal remedy to improve NASH during screening and treatment phase of the trial. The antiNASH agents are defined as thiazolidinediones, vitamin E, metformin, UDCA, SAM-e, betaine, milk thistle, gemfibrozil, anti-TNF therapies, and probiotics. The life-style recommendations were prepared by the NASH CRN Standards of Care Committee and were approved by the Steering Committee to help ensure that the participants in all groups receive standard of care treatment in a consistent manner at all 8 clinical centers.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure requires improvement in NAFLD Activity Score (NAS), after 96 weeks of treatment as determined by liver biopsies performed before and at the end of treatment [35]. The NAS ranges from 0 to 8 (highest activity) and is calculated as the sum of scores of the three components of the histologic scoring system [NAS = steatosis (0–3) + lobular inflammation (0–3) + hepatocyte ballooning (0–2)]. The definition of histologic improvement requires all three of the following criteria: (a) either improvement in NAS by at least 2 points spread across at least 2 of the NAS components or post-treatment NAS of 3 points or less, (b) at least 1 point improvement in the score for ballooning degeneration and (c) no worsening of the fibrosis score.

Secondary outcomes include changes in (a) overall NAS, (b) feature scores including fibrosis, ballooning degeneration, inflammation and steatosis, (c) serum aminotransferase levels, (d) anthropometric measures including body weight, waist-to-hip ratio, waist circumference, triceps skin fold thickness and total body fat, (e) insulin resistance, (f) serum vitamin E levels, (g) cytokines, fibrosis markers, and lipid profile; and (f) health-related quality of life (SF-36).

Sample size justification

The planned sample size for the PIVENS trial was 240 patients with equal allocation to each of the three treatment groups (80 per group). The sample size estimates were based upon a two-group, binomial comparison of the proportions of patients satisfying the primary outcome, improvement in NAS over the course of treatment either with pioglitazone or vitamin E. Since PIVENS had three treatment groups and two primary hypotheses, the assumption was made that the two primary comparisons, pioglitazone vs. placebo and vitamin E vs. placebo, required the same sample size requiring that the type I error estimate be reduced from 0.05 to 0.025 (Bonferroni correction). Expected proportions improved were approximated using pilot data from a 48-week pioglitazone study and from the placebo group in a two-year randomized trial of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) vs. placebo [38]. There were no available data at the time of study design to estimate histological response with vitamin E, which was assumed, for purposes of planning the trial, to be the same as for pioglitazone.

The sample size calculations were performed using the nQuery Advisor 5.0 software [39] with an expected proportion improved in placebo group (assumed=0.14), with an expected proportion improved in pioglitazone or vitamin E group (0.40), with an α level of two-sided type I error (0.025, Bonferroni corrected for two comparisons), and with a β level of type II error (0.10; i.e., 90% power). The number per group, using the above assumptions was 71. Inflating this number by the 10% expected missing data rate yielded approximately 80 patients per group, or a total of 240 for the trial.

Interim analysis

An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), membership appointed by the NIDDK, approved the protocol for the PIVENS trial and is responsible for monitoring the accumulated interim data as the trial progresses to ensure patient safety and to review efficacy. In addition, the DSMB is charged with reviewing the quality and timeliness of data collection. The DSMB is a multidisciplinary group with a written charge provided by the NIDDK. All of the summary recommendations by the DSMB and communication from the NIDDK regarding the DSMB are forwarded to all of the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) overseeing the study.

Interim data on safety measures requested by the DSMB are reviewed at each of the scheduled semi-annual meetings. Serious adverse events are reviewed by the DSMB as they occur and the DSMB reviews quarterly reports by masked treatment groups of incident hepatotoxicities, as well as counts of patients who require more frequent liver function testing due to rises in ALT levels of more than 1.5 times baseline ALT or beyond 250 U/L. The DSMB also examines the trends in ALT or AST levels for each patient who experiences a rise in ALT. One interim efficacy analysis of the primary outcome measure is planned to occur when approximately 50% of the data are complete or when approximately 120 of the 240 patients have completed baseline and 96 week biopsies. O’Brien-Fleming statistical stopping guidelines for efficacy apply [40].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses for the two primary hypotheses will follow the intention-to-treat paradigm, which means that all randomized patients with baseline and 96 week liver biopsies will be included in the treatment group to which they were assigned. Any randomized patient who does not have the requisite biopsies will be considered unimproved on the primary outcome measure and compared by assigned treatment group. Patients not able to be included in the intention-to-treat analyses will be compared to those who are included with respect to demographic and other characteristics.

Since the primary outcome measure, is a binary indicator of improvement in NAFLD activity score after 96 weeks of treatment compared to baseline and since the randomization is stratified by clinic, P-values will be derived from the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test for stratified 2×2 tables [41]. Two P-values will be derived: one comparing proportions improved in the group assigned to pioglitazone compared to the group assigned to placebo and another comparing the group assigned to vitamin E to the group assigned to placebo. Since two primary comparisons are planned, a P-value of 0.025 will be considered significant, applying a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Given the randomized design and adequate size planned for the PIVENS trial, it is unlikely that confounding of the treatment groups by covariates related to the change in histologic activity score will occur. However, if confounding should occur, logistic regression analyses with histologic improvement as the binary response and treatment group indicator and any suspected confounders as covariates will be carried out to determine the sensitivity of the primary P-value to confounding.

The secondary hypothesis that pioglitazone and vitamin E are equally efficacious in achieving histologic improvement, involves the primary outcome measure. Equivalence will be assessed in two ways: (1) a formal test for equivalence, testing that the difference between proportions improved in the pioglitazone and vitamin E groups does not exceed 10% and (2) 95% confidence intervals on the difference in proportions improved.

In general, analyses for outcomes related to other secondary hypotheses will be conducted in two ways. Improvement will be analyzed both as a binary outcome (improved vs. not improved) and also in terms of the numerical change in the outcome. Binary outcomes will be compared using the uncorrected χ2 test for 2×2 table. Numerical changes will be analyzed by descriptively comparing the between-treatment group differences in mean and median changes; P-values will be derived from Wilcoxon rank sum tests for comparison of the distribution of changes in each group. If concerns about confounding arise, logistic regression models for improvement outcomes and linear regression models for numerical change outcomes will be used to correct for the confounding. Analyses for secondary hypotheses will generally involve three separate analyses, one for each treatment group comparison: pioglitazone vs. placebo, vitamin E vs. placebo, and pioglitazone vs. vitamin E. No adjustments for multiple comparisons will be applied to the secondary hypotheses; however, any significant findings will be interpreted taking into account the strength of the finding and its biologic plausibility.

2. Conduct of the trial

Patient selection

Eligible adults (≥ 18 years of age) were identified and recruited at the participating clinical centers starting in January 2005 and by January 2007, 247 patients were enrolled. Determination of eligibility was based on standard of care tests and procedures that were completed during screening. Each patient signed the consent at the screening visit to obtain any tests and procedures needed to finalize eligibility and had a history and physical examination to identify other illness and contraindications for participation.

Inclusion criterion

The study entry was based on a liver biopsy obtained within 6 months before randomization (patient must not have used medications suspected of having an effect on NASH in the 3 months before the biopsy). The histological evidence of NASH was defined as either (a) NAS ≥ 5 with a minimum score of 1 for all of its three components [steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, and lobular inflammation] plus a finding of possible (defined as suspicious or borderline for steatohepatitis) or definite steatohepatitis as judged by the local study pathologist, or (b) NAS=4 with a minimum score of 1 for all of its three components as judged by the local study pathologist and a finding of definite steatohepatitis as judged by 2 out of 3 study pathologists. In summary, when NAS was read as 4 locally, the diagnosis of steatohepatitis for PIVENS eligibility was based on reviews by 3 pathologists with one being the local study pathologist and two others, including the lead NASH CRN pathologists.

Exclusion criteria

Reasons for exclusion of patients were significant alcohol consumption, history of diabetes, evidence of cirrhosis or other forms of chronic liver disease, and history of heart failure (Table 1). Alcohol consumption was ascertained by a structured interview with the Skinner lifetime drinking history questionnaire and by a self-administered alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) with flash cards to remind study participants of drink equivalents. Use of drugs historically associated with NAFLD such as amiodarone, methotrexate, or other known hepatotoxins was also assessed during screening and their use constituted an exclusion.

Table 1.

PIVENS exclusion criteria

|

Run-in period

Patients were not allowed to use any prescription or over-the-counter medication or herbal remedy taken with an intent to improve or treat NASH or liver disease or obesity or diabetes for the 3 months before liver biopsy as well as the 3 months before randomization. Such agents included: TZDs, vitamin E, metformin, ursodiol, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM-e), betaine, milk thistle (silymarin), gemfibrozil, anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies, and probiotics. Prohibited antidiabetic agents included: insulin, biguanides, sulfonylureas, metformin and TZDs. These agents were not to be used during screening nor for the duration of the trial (except in the form of assigned study treatment or treatment for new onset diabetes). If a participant was using a statin or fibrate medication to improve hyperlipidemia during screening, he/she was required to be on a stable dose in the 3 months before liver biopsy and randomization. However, participants were allowed to continue on prescription anti-hyperlipidemic agents, if they were on a stable dose during screening. Any over-the-counter medication or herbal remedy that was being taken with an intent to improve hyperlipidemia was not allowed for at least 3 months before randomization and are discouraged after randomization. Participants were interviewed in a detailed fashion at screening, randomization, and at every clinic visit to document the absence of such use.

Study visit overview

The patient-related activities of the PIVENS trial is divided into 4 phases: (1) screening for eligibility for enrollment (2 visits over a maximum of 24 weeks), (2) randomization (one visit), (3) treatment (15 visits over 96 weeks), and (4) post-treatment observation (one visit 24 weeks after stopping study drugs).

The visit and data collection schedule is summarized in Table 2. Anthropomorphic assessments include body weight and height, body mass index, waist and hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, triceps skin fold thickness, mid-upper arm circumference.

Table 2.

Data collection schedule

| Screening visits |

Follow-up visits Weeks from randomization |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment/Procedure | S1 | S2 | RZ | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 24 | 32 | 40 | 48 | 56 | 64 | 72 | 80 | 88 | 96 | 120 |

| Consent | X | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Baseline medical history | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Followup medical history | . | . | . | . | X | X | . | X | X | X | . | X | . | X | X | X | . | X | X |

| AUDIT, Skinner alcohol question |

. | A | S | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Review of concomitant drugs | X | . | X | . | X | X | . | X | X | X | . | X | . | X | X | X | . | X | X |

| Review for adverse effects | . | . | . | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Drug dispensing | . | . | X | . | X | X | . | X | X | X | . | X | . | X | X | X | . | . | . |

| Review of study drug adherence |

. | . | . | . | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | . |

| Physical exam (Detailed/Focused) |

D | . | . | . | F | F | . | F | D | F | . | D | . | F | F | F | . | D | F |

| DEXA scan for body fat | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| Liver biopsy | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . |

| Block 98 nutrition questionnaire |

. | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| Functional activity questionnaire |

. | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| HR-QOL (SF-36) | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| Liver symptom questionnaire | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| OGTT with insulin and C-peptide |

. | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| Labs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fasting glucose | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . |

| Fasting lipid profile | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| CBC | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| Metabolic panel | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | . |

| Hepatic panel | . | X | . | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| GGT and prothrombin time |

. | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | . |

| HbA1c | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | . |

| Pregnancy test (females) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Microalbuminuria | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | X |

| Serum, plasma for banking | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | X | . | X | . | X | . | X | . | X | X |

| Serum vitamin E (banked serum) |

. | X | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X | . | . | . | . | . | X | . |

| Closeout form | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | X |

Note: Detailed (D) physica includes measurement of height, weight, waist, and hips; vital signs (temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure); triceps skin fold thickness, mid upper arm circumference; examination for scleral icterus and pedal edema and auscultation of the heart and lungs; general physical findings (hepatosplenomegaly, peripheral manifestations of liver disease, ascites, wasting, fetor).

Focused (F) physical includes measurement of height, weight, waist, and hips; vital signs (temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure); examination for scleral icterus and pedal edema and auscultation of heart and lungs.

Metabolic panel: sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphate, BUN, creatinine, uric acid, albumin, total protein.

Hepatic panel: total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase.

Lipid profile: total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL, HDL.

Fasting visits:S1, S2, 16, 24, 32, 48, 64, 72, 80, 96, and 120.

Safety visits:2, 12, 40, 56, and 88.

Randomization

The NASH CRN web-based data management system includes software to check patient eligibility based on keyed case report forms. The web-based eligibility check task was run to list the eligibility checks that the patient has failed and a summary finding that the patient was eligible or ineligible for the trial. The randomization visit could not take place until the eligibility check indicated that the patient was eligible in all items except those that could be completed only at the randomization visit.

The randomization plan was prepared and administered centrally by the Data Coordinating Center (DCC). Requests for randomizations were made by the clinical staff using a web-based application. A study drug assignment was issued only if the PIVENS database showed that the patient was eligible, had signed the consent statement, and had all required baseline data keyed to the database. The randomization scheme assigned patients in permuted blocks of treatments stratified by Clinical Center to minimize local effects of differences in patient populations and management.

Follow-up visits

Participants return for follow-up visits at 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 72, 80, 88, 96, and 120 weeks after randomization. Thus, starting at 16 weeks after randomization, participants are seen at 8 week (2 month) intervals through 96 weeks. The details of various data obtained at each of these follow-up visits are shown in Table 2.

A follow-up liver biopsy is scheduled to be obtained at the week 96 visit. Predefined general guidelines for obtaining the biopsy specimen were provided to each site. Wherever possible, a 16 gauge biopsy needle and a specimen length of at least 1.5 cm was preferred. The slides must be of adequate size (1.5 cm or more) and adequate quality for interpretation. The liver tissue is prepared locally for light microscopy interpretation with stains including hematoxylin and eosin, Masson’s trichrome and iron stain; additionally, a piece of liver tissue is snap frozen and stored at −70 degrees C and set aside for banking and future study.

Standardized questionnaires

Several standardized questionnaires are administered to participants enrolled in the PIVENS trial. Questionnaires were administered at baseline (before randomization) and during follow-up at specified intervals (Table 2). The focus of the individual questionnaires is to obtain information regarding alcohol intake, nutrition, functional activity, health-related quality of life, and liver-related symptoms. The questionnaires selected for use in the PIVENS trial were determined by the NASH CRN Measures and Assessments Committee during development of the trial and included AUDIT and Skinner questionnaires for capturing alcohol consumption, Block 98 nutrition questionnaire for estimating food frequency and quantity over the preceding 12-month period, NHANES III Activity Questionnaire as a measure of functional activity, SF-36 to measure health related quality of life and a liver symptom questionnaire developed by the NASH CRN to capture liver related symptoms during the trial.

Case report forms include baseline and follow-up physical exam and medical history to capture co-morbidities and co-medications in the trial database. Other case report forms constituting the PIVENS trial database include laboratory tests results for eligibility checks at baseline and safety monitoring during follow-up, local and central histology reviews of liver biopsy slides, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan for body fat and bone mineral density, and study drug dispensing form for study drug adherence and accountability.

Specimen banking

Specimens are collected and stored in a central repository for use as approved by the Steering Committee of the NASH CRN. Specimens include serum, plasma, DNA, and liver tissue. The blood samples collected at screening visit 2, and at 16, 32, 48, 64, 80, 96 and 120 week visits are divided into 0.5 mL aliquots and stored frozen at −70 degrees C. Additional blood was collected at the screening visit for extraction of DNA which is stored at −20 degrees C. When possible, a portion of the liver biopsy specimen is collected and stored. The biosamples collected throughout the PIVENS trial are available for investigational use with an ancillary study proposal mechanism as outlined on the NASH CRN web page [42].

3. Results

Enrollment in PIVENS started in January 2005 and ended in January 2007 with 247 patients randomized which was 7 more than planned, so as to allow all registered participants to join the trial, if found to be eligible. A total of 339 patients were registered and screened for the PIVENS trial, 92 of whom (27%) were found ineligible. The failure to meet histological entry criteria and fasting blood glucose >125 mg/dL were the most frequent reasons for ineligibility.

Baseline liver biopsies were scored by the local study pathologist for histological eligibility for trial entry according to the NASH CRN histological scoring system [35]. In addition, all baseline biopsies were reviewed centrally and all follow-up biopsies are scheduled to be reviewed centrally at a multihead microscope using consensus scoring by the NASH CRN Pathology Committee for efficacy assessments. At central review, the pathologists are masked to patient information and to which NASH CRN study protocol produced the biopsy. Although the local pathologist determines the histological eligibility for trial entry, the NAS as determined by the pathology committee at central reviews will be used in efficacy analyses.

The follow-up of PIVENS participants is currently ongoing and data collection including histological findings obtained after 96 weeks of treatment with study medications will be completed in early 2009.

4. Challenges

Clinical trials usually take several years from start to completion. Although the recruitment into PIVENS was completed in a timely manner, the study is still ongoing as it involves approximately two years of treatment and 6 months of further follow-up evaluation. Over this period (2004–2009), external developments are likely, including a growing body of knowledge about the therapies tested, to take into consideration as a trial moves forward. During the conduct of the PIVENS trial, as more post-marketing safety data are gathered on thiazolidinedione effects, adjustments will be needed to the PIVENS procedures, protocol, and consent statement. Two recent examples were the safety concerns associated with the use of thiazolidinediones including pioglitazone with regard to (1) accelerated bone loss and an increased bone fracture risk in older, post-menopausal diabetic women [43–46], and (2) a raised level of warning for congestive heart failure risk [46–48]. In both cases, the NASH CRN Steering Committee responded to these external developments to address the safety concerns and to inform the PIVENS participants in collaboration with the NIDDK, DSMB, and the participating center IRBs. Appropriate changes to the informed consent documents were also made.

5. Summary

PIVENS is a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled therapeutic study of NASH in adult nondiabetics. Three treatment groups include pioglitazone 30 mg per day, vitamin E 800 IU per day and placebo administered for 96 weeks. The primary outcome measure is a change in hepatic histology at week 96 liver biopsy as compared to baseline liver histology using a strict histological scoring system. Compliance with trial protocol and safety of therapeutic interventions are followed closely by a separate DSMB. The enrollment of the required sample size was completed by January 2007 and this ongoing study is expected to be completed by early 2009. The full PIVENS protocol can be requested from the NASH CRN DCC via the Internet [49].

Writing Committee

Members consist of Naga P. Chalasani, Arun J. Sanyal, Kris V. Kowdley, Patricia R. Robuck, Jay Hoofnagle, David E. Kleiner, Aynur Ünalp, James Tonascia, and these authors take full responsibility for the contents of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

PIVENS trial is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. Additional funding to conduct PIVENS trial is provided by the Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc. through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) with the National Institutes of Health.

Grant support: The Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants U01DK061718, U01DK061728, U01DK061731, U01DK061732, U01DK061734, U01DK061737, U01DK061738, U01DK061730, U01DK061713, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This study is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute. Other grant support include following National Institutes of Health General Clinical Research Centers or Clinical and Translational Science Awards: UL1RR024989, M01RR000750, RR02413101, M01RR000827, UL1RR02501401, M01RR000065.

Appendix

The following members of the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network have been instrumental in the design and conduct of PIVENS trial.

Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH: Diane Bringman, RN, BSN; Srinivasan Dasarathy, MD; Kevin Edwards, NP; Carol Hawkins, RN; Yao-Chang Liu, MD; Arthur McCullough, MD (Principal Investigator); Nicholette Rogers, PhD, PA-C; Ruth Sargent, LPN

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Manal Abdelmalek, MD; Anna Mae Diehl, MD (Principal Investigator); Marcia Gottfried, MD (2005–2006); Cynthia Guy, MD; Paul Killenberg, MD; Samantha Kwan, Dawn Piercy, FNP; Melissa Smith

Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN: Prajakta Bhimalli, Naga Chalasani, MD (Principal Investigator); Oscar W. Cummings, MD; Lydia Lee, Linda Ragozzino, Raj Vuppalanchi, MD

Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO: Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD; Joyce Hoffmann, Debra King, RN; Joan Siegner, RN; Susan Stewart, RN; Brent A. Neuschwander-Tetri, MD (Principal Investigator); Judy Thompson, RN

University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA: Cynthia Behling, MD; Lisa Clark, PhD; Tarek Hassanein, MD; Joel E. Lavine, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Deanna Oliver, Heather Patton, MD; Lita Petcharaporn

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA: Kiran Bambha, MD, Nathan M. Bass, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Linda D. Ferrell, MD; Raphael Merriman, MD (2002–2007); Mark Pabst, Monique Rosenthal, Tessa Steel

University of Washington (2002–2007), Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA: Kris V. Kowdley, MD (Principal Investigator); Jody Mooney, MS; James Nelson, PhD; Cheryl Saunders, MPH; Alice Stead, Matthew Yeh, MD, PhD

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA: Sherry Boyett, RN, Melissa J. Contos, MD; Michael Fuchs, MD; Velimir AC Luketic, MD; Bimalijit Sandhu, MD; Arun J. Sanyal, MD (Principal Investigator); Carol Sargeant, RN, MPH; Melanie White, RN

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD: David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD

National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD: Edward Doo, MD; Jay Everhart, MD, MPH; Jay Hoofnagle, MD; Patricia R. Robuck, PhD; Leonard Seeff, MD

Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health (Data Coordinating Center), Baltimore, MD: Pat Belt, BS; Fred Brancati, MD, MHS; Jeanne Clark, MD, MPH; Ryan Colvin, MPH; Michele Donithan, MHS; Mika Green, MA; Rosemary Hollick (2004–2005); Milana Isaacson, Alison Lydecker, Laura Miriel, Alice Sternberg, ScM; James Tonascia, PhD (Principal Investigator); Aynur Ünalp-Arida, MD, PhD; Mark Van Natta, MHS; Laura Wilson, ScM; Kathie Yates, ScM

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:434–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falck-Ytter Y, Younossi ZM, Marchesini G, McCullough AJ. Clinical features and natural history of nonalcoholic steatosis syndromes. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:17–26. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCullough AJ. Update on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:255–262. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Relation of elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity with iron and antioxidant levels in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1821–1829. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. The prevalence and etiology of elevated aminotransferase levels in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:960–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser A, Longnecker MP, Lawlor DA. Prevalence of elevated alanine transaminase among US adolescents and associated factors: NHANES 1999–2004. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1814–1820. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacon BR, Farahvash MJ, Janney CG. Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an expanded clinical entity. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee RG. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a study of 49 patients. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:594–598. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell EE, Cooksley WG, Hanson R, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a follow-up study of forty-two patients for up to 21 years. Hepatology. 1990;11:74–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St, Sauver J, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:113–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teli MR, James OF, Burt AD, Bennett MK, Day CP. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver: a follow-up study. Hepatology. 1995;22:1714–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dam-Larsen S, Franzmann M, Andersen IB, et al. Long term prognosis of fatty liver: risk of chronic liver disease and death. Gut. 2004;53:750–755. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.019984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chitturi S, Farrell GC. Etiopathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:27–41. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1999;107:450–455. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanyal AJ, Campbell-Sargeant C, Mirshahi F, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: association of insulin resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1183–1192. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willner IR, Waters B, Patil SR, et al. Ninety patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: insulin resistance, familial tendency, and severity of disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2957–2961. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chitturi S, Abeygunasekera S, Farrell GC, et al. NASH and insulin resistance: Insulin hypersecretion and specific association with the insulin resistance syndrome. Hepatology. 2002;35:373–379. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagano G, Pacini G, Musso G, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome: further evidence for an etiologic association. Hepatology. 2002;35:367–372. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weltman MD, Farrell GC, Hall P, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Liddle C. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 is increased in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 1998;27:128–133. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalasani N, Gorski JC, Asghar MS, et al. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 activity in non-diabetic patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;37:544–550. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalasani N, Deeg MA, Crabb DW. Systemic levels of lipid peroxidation and its metabolic and dietary correlates in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1497–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilg H, Diehl AM. Cytokines in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. New Engl J Med. 2000;343:1467–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wigg AJ, Robert-Thompson IC, Dymock RB, et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, intestinal permeability, endotoxaemia, and tumor necrosis factor α in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:206–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Wehmeier KK, Oliver D, Bacon BR. Improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis after 48 weeks of treatment with the PPAR-gamma ligand rosiglitazone. Hepatology. 2003;38:1008–1017. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanyal AJ, Mofrad PS, Contos MJ, et al. A pilot study of vitamin E and pioglitazone for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Promrat K, Luchman G, Uwaifo GI, et al. A pilot study of pioglitazone treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2004;39:188–196. doi: 10.1002/hep.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2297–2307. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavine JE. Vitamin E treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children: a pilot study. J Pediatr. 2000;136:734–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasegawa T, Yoneda M, Nakamura K, Makino I, Terano A. Plasma transforming growth factor-beta1 level and efficacy of alpha- tocopherol in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1667–1672. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrison SA, Torgerson S, Hayashi P, Ward J, Schenker S. Vitamin E and vitamin C treatment improves fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2485–2490. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kugelmas M, Hill DB, Vivian B, Marsano L, McClain CJ. Cytokines and NASH: a pilot study of the effects of lifestyle modification and vitamin E. Hepatology. 2003;38:413–419. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Hepatology. 2003;35:244. doi: 10.1002/hep.510370203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bendich A, Machlin LJ. Safety of oral intake of vitamin E. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:612–619. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.3.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Machlin LJ. Use and safety of elevated dosages of vitamin E in adults. Int J Vitam Nutr Res Suppl. 1989;30:56–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Heathcote EJ, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:770–778. doi: 10.1002/hep.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elashoff, et al. nQuery Advisor Version 5.0 User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleming TR, Harrington DP, O’Brien PC. Designs for group sequential test. Control Clin Trials. 1984;5:348–361. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(84)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42. NASH CRN Ancillary Studies Policy can be accessed at http://www.jhucct.com/nash/open/ancillary/ancstudies.htm.

- 43.Schwartz AV, Sellmeyer DE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Thiazolidinedione use and bone loss in older diabetic adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3349–3354. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grey A, Bolland M, Gamble G, et al. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist rosiglitazone decreases bone formation and bone mineral density in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1305–1310. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.for the Adopt Study Group. Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2427–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.for the PROactive Investigators. Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJA, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lago RM, Singh PP, Nesto RW. Congestive Heart Failure and Cardiovascular Death in Patients with Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Given Thiazolidinediones: a Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Lancet. 2007;370:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lincoff AM, Wolski K, Nicholls SJ, Nissen SE. Pioglitazone and Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Metaanalysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2007;298:1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. PIVENS Trial Protocol can be accessed at http://www.jhucct.com/nash/open/studies.htm.