Abstract

Betaine homocysteine S-methyltransferase (BHMT) catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from betaine to homocysteine forming dimethylglycine and methionine. We previously showed that inhibiting BHMT in mice by intraperitoneal injection of S-(α-carboxybutyl)-DL-homocysteine (CBHcy) results in hyperhomocysteinemia. In the present study, CBHcy was fed to rats to determine whether it could be absorbed and cause hyperhomocysteinemia as observed for the intraperitoneal administration of the compound in mice. We hypothesized that dietary administered CBHcy will be absorbed and will result in the inhibition of BHMT and cause hyperhomocysteinemia. Rats were meal-fed every 8 hours an L-amino acid-defined diet either containing or devoid of CBHcy (5 mg/meal) for 3 days. The treatment decreased liver BHMT activity by 90% and had no effect on methionine synthase, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase and CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase activities. In contrast, cystathionine β-synthase activity and immunodetectable protein decreased (56 and 26%, respectively) and glycine N-methyltransferase activity increased (52%) in CBHcy-treated rats. Liver S-adenosylmethionine levels decreased by 25% in CBHcy-treated rats and S-adenosylhomocysteine levels did not change. Further, plasma choline decreased (22%) and plasma betaine increased (15-fold) in CBHcy-treated rats. The treatment had no effect on global DNA and CpG island methylation, liver histology and plasma markers of liver damage. We conclude that CBHcy mediated BHMT inhibition causes an elevation in total plasma homocysteine that is not normalized by the folate-dependent conversion of homocysteine to methionine. Further, metabolic changes caused by BHMT inhibition affect cystathionine β-synthase and glycine N-methyltransferase activities, which further deteriorate plasma homocysteine levels.

Keywords: BHMT, betaine, rat, homocysteine, sulfur amino acids

1. Introduction

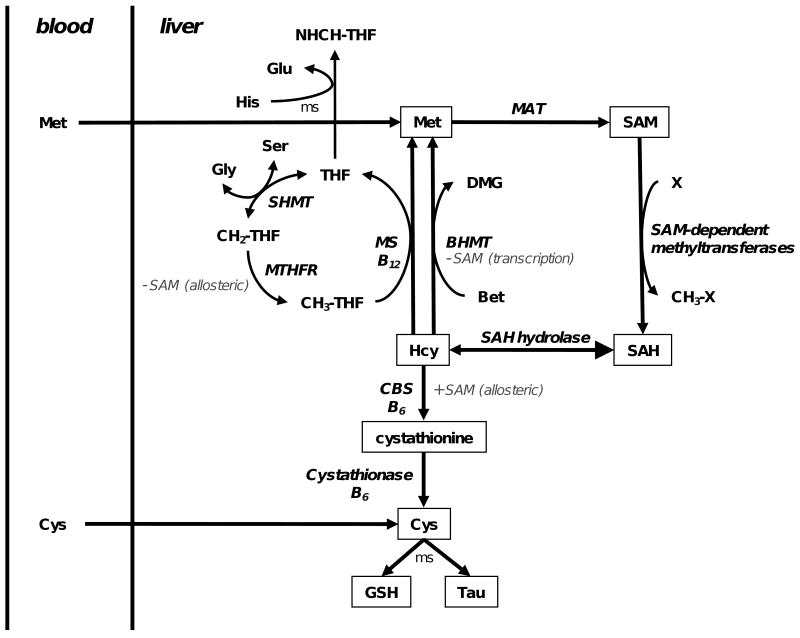

Betaine homocysteine S-methyltransferase (BHMT) is an enzyme of the choline oxidation pathway that catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from betaine to homocysteine (Hcy) forming dimethylglycine and methionine (Figure 1). BHMT is a cytosolic enzyme expressed at very high levels (∼1% total soluble protein) in rat liver, but it is essentially absent in the other organs of the adult rat [1,2]. The expression of BHMT in rat liver is affected by the level of dietary methionine, choline, and betaine [3-6].

Fig. 1.

Homocysteine metabolism in the liver. Homocysteine (Hcy) is methylated to methionine (Met) by cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase (MS) and betaine homocysteine S-methyltransferase (BHMT) using 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (CH3-THF) and betaine (Bet) as the methyl donors, respectively. Methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) adenylates Met to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which is a methyl donor for numerous SAM-dependent methyltransferases in the cell. SAM-dependent methyl transfer yields a methylated product (CH3-X) and S-adenosylhomosysteine (SAH). SAH hydrolase catalyzes the reversible hydrolysis of SAH to Hcy and adenosine. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) catalyzes a one carbon transfer from serine (Ser) to tetrahydrofolate (THF) forming methylene-THF (CH2-THF) and glycine (Gly), and then CH2-THF is reduced to CH3-THF by methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). Transsulfuration pathway. Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) conjugates Ser and Hcy to form cystathionine (CTH), which is hydrolyzed to cysteine (Cys), α-ketobutyrate and ammonium ion by cystathionase. Cys can be utilized for protein, glutathione (GSH) or taurine (Tau) synthesis in a multiply step (ms) reaction. Histidine oxidation. Histidine (His) is sequentially oxidized to glutamate (Glu) and formimino-THF (NHCH-THF). Regulation by SAM. SAM is an allosteric inhibitor of MTHFR (indirectly decreases Hcy methylation) and is a required allosteric activator of CBS (increases Hcy catabolism). SAM also inhibits BHMT transcription.

We previously described the synthesis of S-(α-carboxybutyl)-DL-homocysteine (CBHcy) and showed it to be a potent dual substrate inhibitor of recombinant human BHMT in vitro [7]. We later showed that CBHcy does not inhibit methionine synthase (MS), cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) or cystathionase activities in mouse liver extracts [8]. The latter study also investigated the effect of intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of CBHcy in mice. A single injection of CBHcy (1 mg) to fasted mice caused a transient 2.7-fold elevation of total plasma Hcy (tHcy). When CBHcy was co-administered with methionine (3 mg), tHcy levels were 2.2-fold higher 2 hours after the injection compared to methionine-treated controls. When administered repeatedly every 12 hours (6 doses total), CBHcy-treated mice had a 7-fold elevation of tHcy, a 51% decrease in liver S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and 65% decrease in SAM-to-S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) ratio. This was the first study to show that inhibiting flux through BHMT causes disturbances in sulfur amino acid metabolism, including tHcy levels.

The nutritional and genetic factors that influence tHcy in humans have been the subject of intense research since elevated levels of tHcy have been associated with an increased risk for thrombosis, vascular disease and some psychological disorders [9,10]. The absence of a BHMT knock out mouse makes the use of CBHcy-treated animals a good model to study metabolic changes caused by a potential deficiency of BHMT in humans and to assess whether the pharmacological modulation of this enzyme might be of any clinical interest. However, for conducting long-term inhibition studies in rodents, multiply i.p. injections of the inhibitor are not ideal because of the discomfort it causes to the animals. We designed the present study to address the hypothesis that oral administration of CBHcy to rats will effectively inhibit BHMT activity and cause hyperhomocysteinemia as previously shown for the i.p. administration in mice [8]. To test this hypothesis, we added CBHcy (5 mg/meal) to L-amino acid-defined diet and fed it to rats every 8 hours to simulate the regime that was implemented for the i.p. administration studies. We selected an 8-hour interval between the meals to assure constant inhibition of BHMT, since following a single dose of CBHcy (i.p.) in mice, BHMT activity was strongly inhibited for 8 hours and only returned to normal activity at 24 hours [8]. Following 3 days of this regime (9 meals total), we collected plasma and liver and measured Hcy levels. The reason we switched to rats was driven by the need to secure enough plasma and tissue material for more enzyme and metabolite analyses and the fact that rats are more easily trained than mice. Here we show that CBHcy added to diet is effectively absorbed and delivered to the liver where it inhibits BHMT activity, which results in hyperhomocysteinemia. We conclude that administration of CBHcy in the diet is a good alternative approach to study BHMT's role in the Hcy metabolism, and because we did not find any adverse effects of the treatment, we recommend it for use in long-term studies that seek to determine whether inhibition of BHMT by this compound might have further clinical or experimental utility.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Materials

Ammonium formate, HPLC grade acetonitrile and water, choline chloride, and betaine hydrochloride were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). d9-betaine chloride and d9-choline chloride were from CDN Isotopes (Quebec, Canada). [3H]dCTP was obtained from NEN Life Science Products (Boston, MA, USA). CBHcy was synthesized according to method described by Jiracek et al. [7].

2.2. Animals and treatments

Fisher 344 rats (male, ∼70 g, Harlan) were individually housed in hanging wire cages and trained to meal feed using a L-amino acid-defined purified diet (AIN-93G, Dyets) [11]. Meals (10 g) were given every 8 hours and the animals were allowed to feed for 2 hours (0600 to 0800, 1400 to 1600 and 2200 to 0000). After 3 days of training the animals were randomly assigned a treatment group (control or CBHcy, n = 5/group) so that their mean body weights did not differ. During the treatment period, each rat received either 1 g of AIN-93G (control) or 1 g of AIN-93G containing 5 mg of CBHcy (CBHcy) at the beginning of each meal. After this food was consumed (∼15 min), AIN-93G was provided ad libitum to both groups for the reminder of the 2 hour period. Food intake and weight gain were monitored throughout the study. After 3 days of treatment (9 meals total), rats were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation 6 hours after initiation of their last meal, which consisted of 1 g of control or CBHcy diet. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture into EDTA-coated tubes and livers were excised and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at -80 °C until analysis. A portion of liver was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histological analysis. The animal use described here was approved by the University of Illinois Laboratory and Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3. Clinical chemistry

Plasma glucose, urea nitrogen, albumin, albumin to globulin ratio, chloride, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, bicarbonate, anion gap, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, creatine kinase, sorbitol dehydrogenase and bile acids were determined by the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at the College of Veterinary Medicine in Illinois (Urbana, IL, USA). All parameters were measured on Hitachi 917 chemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) using Roche reagents for all of the analytes except for sorbitol dehydrogenase (Catachem, Bridgeport, CT) and bile acids (Diazyme, Poway, CA).

2.4. Enzyme activities and protein abundance

The preparation of liver extract, the respective assays for BHMT, CBS and MS activities, as well as the abundance of BHMT protein were performed as previously described in detail [8]. The activity of glycine N-methyltransferase (GNMT) was measured as described by Cook and Wagner [12] with minor modifications [13], and the abundance of CBS protein was determined as described by Tange et al. [1]. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferse activity (PEMT) was determined by the method described by Ridgway and Vance [15], and CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase activity (CT) was measured according to the method of Vance et al. [16]. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) activity was measured as described by Chen et al. [17]. A unit of activity (U) for each enzyme is defined as nmol product formed per hour.

2.5. Liver and plasma metabolites

Liver SAM and SAH, and plasma total glutathione were determined as recently described in detail [8]. For total glutathione determinations, frozen liver samples were homogenized in 4 volumes (wt/v) of 50 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2 mmol/L EDTA; centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 45 min; and then the supernatants were processed by the same procedures used for plasma. The amino acid pools of liver and plasma were measured using a BioChrom 30 amino acid analyzer using procedures previously described [18,19].

Plasma choline and betaine were determined using a LC/MS procedure. In brief, plasma (30 μl) proteins were precipitated by adding three volumes of acetonitrile containing 10 μmol/L of d9-betaine and 10 μmol/L of d9-choline [20]. Following centrifugation (5800g; 2 min), the supernatants (5 μL) were injected into an Agilent 1100 series LC system (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and metabolites were separated on a ZORBAX Sil (4.6 × 150 mm, 5-micro) column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a 15 mM ammonium formate (mobile phase A) and acetonitrile (mobile phase B) gradient with a 300 μl/min flow rate. The linear gradient was 0-0.5 min, 75% B; 5 min, 20% B; 7-12 min, 100% B; 12.5-17.5 min, 0% B; and 18-25 min, 75% B. A clean run of 100% B followed by 100% A for 5 min, respectively, and then 75% B for 5 min was preformed after every 10 samples followed by a blank run to avoid any carryover and ensure optimum column performance. Positive ion mass spectra were acquired using an Agilent MSD Trap XCT Plus mass spectrometer equipped with an ESI source (Santa Clara, CA, USA). For best sensitivity, positive ESI signals from standard betaine and choline solutions were tuned with the use of a Kd Scientific 789100A model syringe pump (Holliston, MA, USA) connected directly to the ion source via PEEK tubing. Nitrogen was used as both the nebulizer and drying gas and kept at 35 psi and 9 L/min, respectively. The capillary voltage was set to 4.5 kV. The heated capillary of ESI source was kept at 350 °C during the analysis. The quantitation of betaine and choline were performed by multiple reaction monitoring. The following transitions were recorded: betaine, m/z 118 → 59; d9-betaine, 127 → 68; choline, m/z 104 → 60; and d9-choline, m/z 113 → 69. Data collection and analysis was performed by Agilent Software Chemstation for LC 3D system Rev B.01.03 (Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.6. Global DNA and CpG island methylation

Liver genomic DNA was isolated using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and global DNA and CpG island methylation was assessed using the method described by Pogribny et al. [21].

2.7. Histochemistry

Rat livers were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (22 h) and then stored in 70% ethanol until embedded in paraffin. Paraffin slices (3 μm) were mounted onto glass slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and evaluated for presence of fat droplets.

2.8. Statistical analyses

The data are presented as means ± SEM. Student's t-test was performed to test for differences between the means of controls (N=5) and CBHcy-treated (N =5) rats (SigmaStat 3.0). For clinical chemistry data, controls (N=4) and CBHcy-treated rats (N=5) were analyzed and the data are presented as means ± SD. A P value of less or equal to 0.05 was considered significant. Post-hoc analysis using Cohen's effect size (d), sample size (N=5) and α set at 0.05 was performed a posteriori (GPower3.1) to determine the achieved power (1-β) [22]. For measurements that were statistically significant the power ranged from 0.749 to 1.0.

3. Results

3.1. Growth and liver histology

Food intake and weight gain did not differ between CBHcy treated and control rats. The rats consumed an average of 10 ± 1 g of diet/day and had an average weight gain 9.2 ± 1.0 g during the 3 day study period. There were no differences in liver histology observed between the CBHcy-treated and control rats (data not shown).

3.2. Clinical chemistry

Plasma glucose (control 119.0 ± 3.7 vs. CBHcy 130.4 ± 15.2 mg/dl), urea nitrogen (control 5.9 ± 0.6 vs. CBHcy 5.1 ± 0.3 mg/dl), albumin (control 3.8 ± 0.1 vs. CBHcy 3.6 ± 0.1 g/dl), albumin-to-globulin ratio (control 3.2 ± 0.1 vs. CBHcy 3.3 ± 0.1), chloride (control 84.4 ± 0.8 vs. CBHcy 81.8 ± 1.8 mmol/l), phosphorus (control 9.2 ± 0.2 vs. CBHcy 9.5 ± 0.2 mg/dl), potassium (control 4.6 ± 0.1 vs. CBHcy 4.6 ± 0.0 mmol/l), sodium (control 214.4 ± 2.5 vs. CBHcy 220.2 ± 7.1 mmol/l), bicarbonate (control 27.6 ± 0.8 vs. CBHcy 28.4 ± 1.1 mmol/l), anion gap (control 106.1 ± 2.8 vs. CBHcy 114.4 ± 9.1), alanine aminotransferase (control 34.0 ± 1.8 vs. CBHcy 35.6 ± 1.1 U/l), alkaline phosphatase (control 2.0 ± 0.5 vs. CBHcy 3.2 ± 2.0 U/l), creatine kinase (control 380.8 ± 26.1 vs. CBHcy 425.0 ± 103.7 U/l), sorbitol dehydrogenase (control 7.1 ± 0.6 vs. CBHcy 5.5 ± 0.9 U/l), bile acids (control 12.2 ± 1.9 vs. CBHcy 14.6 ± 1.4 μmol/l) were not different between the control and CBHcy treated rats.

3.3. Liver SAM, SAH and glutathione

Liver SAM decreased by 25% in CBHcy-treated rats (49.4 ± 3 vs. 36.9 ± 3 nmol/g liver; P < 0.05) while SAH was not affected (17.1 ± 1.1 vs. 17.4 ± 1.9 nmol/g liver), consequently the SAM-to-SAH ratio decreased by 21%. Liver glutathione was unaffected by CBHcy treatment (control 4.76 ± 0.19 vs. CBHcy 3.96 ± 0.36 μmol/g liver).

3.4. Liver enzymes

BHMT activity in liver extracts was 90% lower (Table 1) while liver BHMT protein increased 2-fold in CBHcy treated rats (data not shown). MS, MTHFR, PEMT and CT activities were not affected by the treatment. CBHcy-treated rats had 56% lower CBS activity, which was accompanied by a decrease in CBS protein (26%; data not shown). GNMT activity increased by 52% in CBHcy treated rats (Table 1).

Table 1.

The effect of CBHcy-mediated BHMT inhibition on liver enzyme activities of rats (n = 5) maintained on L-amino acid-defined diet either containing (CBHcy) or devoid (control) of CBHcy (5mg/meal) for 3 days.

| Enzyme Activity [U/mg] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Control | CBHcy |

| BHMT | 62.7 ± 0.7 | 6.1 ± 0.5* |

| MS | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| MTHFR | 11.7 ± 0.8 | 11.5 ± 0.6 |

| PEMT | 20.3 ± 1.2 | 20.3 ± 2.1 |

| CT | 116.2 ± 2.2 | 120.1 ± 4.4 |

| CBS | 115.2 ± 4.8 | 50.6 ± 7.0* |

| GNMT | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 0.7* |

Enzyme activities were determined as described in the Methods and materials section. Differences between control and CBHcy group were tested using Student's t-test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

3.5. Plasma and liver free amino acid pools

Liver methionine and cystathionine did not differ between the two groups, but liver taurine (74%), serine (50%), aspartate (36%) and glutamate (46%) significantly decreased in the CBHcy-treated rats. Liver Hcy was below the limits of detection in our assay system. Plasma methionine (21%), α-aminobutyric acid (38%), alanine (30%) and serine (15%) significantly decreased and there was a significant increase in plasma histidine (37%), Hcy (276%) and glycine (25%) in the CBHcy-treated group compared to controls (Table 2). Plasma cystathionine was unaffected by CBHcy treatment.

Table 2.

The effect of CBHcy-mediated BHMT inhibition on plasma and liver amino acids and ammonia of rats (n = 5) maintained on L-amino acid-defined diet either containing (CBHcy) or devoid (control) of CBHcy (5mg/meal) for 3 days.

| Plasma [μmol/L] | Liver [nmol/mg protein] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CBHcy | Control | CBHcy | |

| α-Aminobutyric acid | 24.5 ± 1.3 | 15.2 ± 1.2* | 1.04 ± 0.20 | 0.77 ± 0.10 |

| Ammonia | 64.9 ± 3.2 | 82.5 ± 5.8* | 20.4 ± 0.7 | 23.0 ± 1.5 |

| Alanine | 444.1 ± 21.6 | 311.2 ± 20.0* | 54.9 ± 7.9 | 44.3 ± 6.4 |

| Asparate | 28.4 ± 0.9 | 32.1 ± 2.8 | 22.0 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.4* |

| Cystathionine | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.042 ± 0.01 | 0.047 ± 0.01 |

| Cysteine (total) | 218.2 ± 15.5 | 195.0 ± 9.7 | ND | ND |

| Glycine | 226.0 ± 11.6 | 283.2 ± 2.1* | 19.7 ± 1.3 | 17.0 ± 1.1 |

| Glutamic acid | 104.2 ± 7.9 | 121.7 ± 15.3 | 17.2 ± 1.3 | 9.3 ± 2.1* |

| Histidine | 43.4 ± 2.1 | 59.5 ± 1.4* | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.3 |

| Homocysteine (total) | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 15.8 ± 2.7* | < 0.16 | < 0.16 |

| Methionine | 31.7 ± 2.3 | 25.0 ± 0.7* | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.13 |

| Serine | 257.5 ± 13.6 | 216.5 ± 5.0* | 9.3 ± 1.3 | 4.6 ± 0.4* |

| Taurine | 190.0 ± 7.4 | 184.8 ± 6.9 | 78.1±7.8 | 20.2 ± 2.2* |

Levels of amino acids and ammonia were determined as described in the Methods and materials section. Differences between control and CBHcy group were tested using Student's t-test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

ND Not detected.

3.6. Plasma choline and betaine

CBHcy-treated animals had lower plasma choline (16.6 ± 0.9 vs. 12.8 ± 0.7 μmol/L; P < 0.05) and a 15-fold increase in plasma betaine (124 ± 4 vs. 1885 ± 178 μmol/L; P < 0.05).

3.7. Global DNA and CpG island methylation

CBHcy treatment did not statistically impact global DNA methylation (5842 ± 589 vs. 4814 ± 365 DPM/μg DNA) nor CpG island methylation (214 ± 36 vs. 175 ± 32 DPM/μg DNA).

4. Discussion

A previous study using mice showed that a single dose of CBHcy (1 mg) administered i.p. significantly reduced BHMT activity for at least 8 hours and concomitantly and reciprocally increased tHcy [8]. In this study, we investigated whether CBHcy elicited changes in sulfur amino acid and one carbon metabolism when delivered orally over a 3 day period. To accomplish this, rats were trained to meal-feed and were given CBHcy (5 mg/meal) at the beginning of meals, which were provided every 8 hours. At the time of death (6 h post-treatment), BHMT activity was 90% lower in the liver extracts of CBHcy-treated animals compared to controls and plasma betaine and tHcy levels were increased 15- and 4-fold, respectively. Since BHMT is the only known enzyme to use betaine, the increase in plasma betaine provides the most direct evidence that dietary intake of CBHcy inhibits BHMT activity in vivo.

Low levels of dietary methionine, choline and/or some vitamins (folic acid and B12) are known to cause fatty liver in rodents resulting from decreased VLDL secretion, due to decreased phosphatidylcholine (PC) synthesis [23]. Liver can synthesize PC via two distinct pathways; CDP-choline pathway and PEMT mediated reaction. CT catalyzes the rate limiting step in PC synthesis via CDP-choline pathway, which is present in all nucleated cells and produces approximately 70% of liver PC. PEMT is a liver specific enzyme that requires three SAM-derived methyl groups to form one molecule of PC. Studies in mice have shown that PC synthesis via PEMT is a major draw on the methyl groups derived from SAM [24], and that PEMT-derived PC is important for VLDL biosynthesis and thus normal secretion of triglycerides from liver [25]. In the previous study, i.p. administration of CBHcy in mice [8] resulted in a reduction of liver SAM (51%), and therefore in this follow up study we sought to determine whether CBHcy causes fatty liver. Note that compared to 3 day i.p. injections of CBHcy (51% reduction of liver SAM), for reasons that we do not currently understand, oral administration of CBHcy only decreased liver SAM by 25%.

CBHcy treated rats did not develop fatty liver and had normal plasma triglycerides. Activities of the liver enzymes of PC synthesis did not change and the levels of SAM decreased only slightly in the CBHcy-treated animals. Considering that mice deficient in PEMT do not develop fatty liver and secrete normal levels of triglycerides [26] unless fed a choline deficient [27] or high-fat/high-cholesterol [28] diet, it is not surprising that we did not observe any changes in plasma triglycerides or liver histology. Furthermore, the dietary conditions employed in this study included ample methionine (4.5 g/kg) and choline bitartrate (2.5 g/kg). To determine whether CBHcy-induced decrease in SAM affects PEMT-mediated PC synthesis, different dietary conditions, for example choline deficient or high-fat/high-cholesterol diet, would have to be administered in combination with CBHcy. The decrease in plasma choline in the CBHcy-treated rats may reflect an increased utilization of choline for PC synthesis via the CDP-choline pathway.

It has been proposed that BHMT and folate-dependent MS contribute equally to Hcy methylation in the liver [29]. The reduction in the flux through the BHMT-catalyzed reaction and the concomitant decrease in SAM (25%) caused by CBHcy treatment could elicit a compensatory change in flux through the folate-dependent Hcy methylation cycle. SAM is an allosteric inhibitor of MTHFR activity, and at physiological concentrations of NADPH, the enzyme has an inhibition constant for SAM of 3 μM in the absence of SAH [30]. SAH reverses the inhibitory effect of SAM and its concentration in the liver is estimated to be 50-70 μM. Thus the enzyme is generally believed to be sensitive to the SAM-to-SAH ratio of the liver cell. It is reasonable to suggest, therefore, that MTHFR could be less inhibited in the CBHcy-treated group thereby increasing the supply of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate for the MS-dependent remethylation of Hcy. Increased utilization of 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate by MTHFR would increase demand on its synthesis by serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Indeed, in the CBHcy group liver serine decreased 50% and plasma glycine increased 24%, perhaps denoting increased flux thru serine hydroxymethyltransferase.

Mice consuming CBHcy had increased liver GNMT activity, which is an abundant enzyme in liver that catalyzes the SAM-dependent conversion of glycine to sarcosine (N-methylglycine). GNMT is allosterically inhibited by 5-methyltetrahydrofolate and this enzyme is believed to have a significant role in the regulation of the liver SAM-to-SAH ratio [13]. If CBHcy treatment enhances flux through MTHFR and MS to promote folate-mediated methionine synthesis, as discussed above, it is possible that this treatment also causes a reduction in liver 5-methyltetrahydrofolate. This could explain the enhanced GNMT activity measured in the liver extracts of CBHcy-treated rats. Elevated GNMT activity could also contribute to the reduced levels of hepatic SAM and elevated levels of tHcy observed in these animals.

The effect of CBHcy treatment on histidine is another indication that CBHcy treatment might be affecting folate-dependent one carbon metabolism. An intermediate of histidine oxidation, formiminoglutamate, is converted to glutamate by formiminoglutamate formiminotransferase, a folate-dependent enzyme. Elevated plasma or urinary formiminoglutamate is a marker of folate deficiency. It is interesting to note that histidine levels were increased by 37% in the plasma of CBHcy-treated rats compared to controls. These data suggest that histidine oxidation decreased as a result of tetrahydrofolate coenzymes being preferentially recruited to support methylenetetrahydrofolate and methyltetrahydrofolate synthesis. The effects of CBHcy on liver folate pools are speculative at this juncture and future work will include quantifying the one carbon substitutions on liver folate.

The mechanism by which CBS protein abundance and activity decreased in the CBHcy treated mice is not known. We have previously shown that CBS activity is not affected by CBHcy in vitro [8]. It is interesting to note that mice deficient in methionine S-adenosyltransferase 1A have elevated CBS activity (4-fold) and methionine levels (776%) [31]. In contrast, methionine restriction was shown to decrease CBS activity [32] and in our study, CBHcy treated mice had a slight decrease in plasma methionine (23%). This suggests that changes in CBS expression may be affected by methionine concentrations. Furthermore, although CBHcy treatment caused changes in CBS activity and SAM levels, SAM is a positive allosteric regulator of CBS activity and its binding stabilizes the protein [33], these changes did not affect plasma and liver cystathionine and plasma cysteine levels. We also measured two downstream metabolites of the transsulfuration pathway, gluthathione and taurine, which are discussed below.

In this study BHMT inhibition did not affect glutathione levels. Cysteine is the rate-limiting factor for glutathione synthesis and is supplied by the diet and produced de novo via the transsulfuration pathway. In the present study, rats were maintained on a diet containing ample cysteine and methionine. Plasma cysteine did not differ between controls and CBHcy-treated rats, and liver cysteine was not detected using the procedure we used to analyze liver extracts. The observation that a modest decrease in CBS activity/abundance does not affect cysteine and glutathione levels is in agreement with the findings of others. In rats, the incorporation of dietary cysteine into liver glutathione is not greatly affected by the methionine content of the diet [34]. Furthermore, although heterozygous CBS deficient mice have 60% lower CBS activity than wild type mice their cysteine and glutathione levels do not significantly differ [35,36]. Combined, these data suggest that the modest reduction of methionine found in the liver and plasma of CBHcy-treated rats did not significantly impact the availability of cysteine for glutathione synthesis.

It is interesting that the large increase in plasma betaine (15-fold) observed in CBHcy-treated rats was accompanied by a significant decrease in liver taurine (74%), a sulphonic amino acid derived from cysteine. Taurine and betaine are compatible organic osmolytes and according to the compatible osmolyte principle, the total osmolality of an organ is maintained by the entire complement of organic osmolytes combined rather than a steadfast maintenance of individual osmolytes within specific ranges [37]. Thus, it is possible that taurine synthesis was specifically down regulated in the CBHcy-treated group because of the reduced rate of betaine catabolism. Similarly, taurine transporter knock out mice, which have liver taurine levels that are 71% lower than wild type mice, have significantly higher levels of betaine, sorbitol and other organic solutes in liver [38]. Besides being an important osmolyte, taurine is used in the synthesis of taurocholic acid in liver and has been shown to mediate anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in in vitro and in animal models [39]. Furthermore, a few epidemiological studies suggest that taurine may be protective against coronary heart diseases [40,41]. It would be interesting to assess cardiovascular function and oxidative stress markers in CBHcy-treated rats and to determine taurine levels in other tissues.

Disturbances in either Hcy methylation to methionine or transsulfuration to cysteine lead to an increase in tHcy, which is associated with an increased risk of all forms of vascular disease [42], neural tube defect [43,44], and Alzheimer's disease [45,46]. The present study confirms the hypotheses stating that CBHcy administered in the diet can be absorbed in the small intestine, delivered to the liver, and inhibit BHMT activity causing hyperhomocysteinemia.

There are several limitations to consider with respect to our model. CBHcy is a relatively new compound and to date no data is available on its toxicity, absorption, degradation and/or excretion. Although, the dose used in this study appears not to have an adverse effect on liver histopathology, enzyme markers of organ damage or DNA methylation, a long-term study is needed to investigate these parameters. For example rats fed a methyl-deficient diet exhibit hypomethylation of DNA and tRNA and increased DNA synthesis in the liver after only one week on the diet [47]. Further, CBHcy is an S-alkyl analog of Hcy and therefore it could interfere with absorption of other amino acids and affect their homeostasis independently of BHMT inhibition. Hcy can use systems L, A and y+L to be transported across the microvillous plasma membrane of human placenta [48]. Thus high concentrations of CBHcy could potentially compete with endogenous amino acids for transport.

A genetic disruption of Bhmt gene could potentially result in an elevation in post-methionine load and/or fasting tHcy in humans. To date however, the reported Bhmt mutations (199G to S, 406Q to H) and a polymorphism (239R to Q) do not show any relevance to hyperhomocysteinemia [49,50,51] nor do their kinetics properties differ from the wild type enzyme (Evans, unpublished data). A significant decrease of dimethylglycine in individuals harboring 239R to Q in one or both alleles is the only known change in metabolite concentration reported associated with a spontaneous Bhmt mutation [52]. In addition, 742G to A mutation has been indentified to be an increased risk factor for abruption [53] and recently a genetic association was identified between premature ischaemic stroke and haplotypes in 7 genes coding for enzymes of methionine metabolism including Bhmt [54]. In summary, altered BHMT expression and/or activity has not been identified to affect tHcy in humans. A model of reduced BHMT activity using CBHcy is an excellent alternative to Bhmt knock out mouse and advances our understanding of Hcy metabolism.

The present study demonstrates that oral administration of CBHcy, a specific and potent inhibitor of BHMT activity, effectively inhibits BHMT in the liver and causes hyperhomocysteinemia. We conclude that BHMT activity is necessary for normal Hcy metabolism, and that MS cannot fully compensate for reduced BHMT activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dennis Vance and Sandra Ungarian for measuring liver phosphatidyl-ethanolamine N-methyltransferase and CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase activities. This work was supported by the NIH (DK52501, T.A.G.), the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (P207/10/1277, J.J.) and the Research Project of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic (Z40550506, J.J.).

Abbreviations

- Bet

betaine

- BHMT

betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase

- CBHcy

S-(α-carboxybutyl)-DL-homocysteine

- CBS

cystathionine β-synthase

- CH2-THF

methylenetetrahydrofolate

- CH3-THF

methyltetrahydrofolate

- CH3-X

methylated product

- CT

CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase

- CTH

cystathionine

- Cys

cysteine

- GSH

glutathione

- Gly

glycine

- GNMT

glycine N-methyltransferase

- Hcy

homocysteine

- His

histidine

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- MAT

methionine adenosyltransferase

- Met

methionine

- MS

methionine synthase

- ms

multiple steps

- MTHFR

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PEMT

phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- Ser

serine

- SHMT

serine hydroxymethyltransferase

- Tau

taurine

- tHcy

total plasma homocysteine

- THF

tetrahydrofolate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McKeever MP, Weir DG, Molloy A, Scott JM. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase: organ distribution in man, pig and rat and subcellular distribution in the rat. Clin Sci. 1991;81:551–6. doi: 10.1042/cs0810551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delgado-Reyes CV, Wallig MA, Garrow TA. Immunohistochemical detection of betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase in human, pig, and rat liver and kidney. Arch Bioch Bioph. 2001;393:184–6. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park EI, Garrow TA. Interaction between dietary methionine and methyl donor intake on rat liver betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase gene expression and organization of the human gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7816–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein JD, Harris BJ, Martin JJ, Kyle WE. Regulation of hepatic betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase by dietary methionine. Bioch Bioph Res Com. 1982;108:344–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91872-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelstein JD, Martin JJ, Haris BJ. Effect of dietary cysteine on methionine metabolism in rat liver. J Nutr. 1986;218:169–73. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelstein JD, Martin JJ, Haris BJ, Kyle WE. Regulation of hepatic betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase by dietary betaine. J Nutr. 1983;113:519–21. doi: 10.1093/jn/113.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiracek J, Collinsova M, Rosenberg I, Budesinsky M, Protivinska E, Netusilova H, Garrow TA. S-alkylated homocysteine derivatives: new inhibitors of human betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3982–9. doi: 10.1021/jm050885v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collinsova M, Strakova J, Jiracek J, Garrow TA. Inhibition of betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase causes hyperhomocysteinemia in mice. J Nutr. 2006;136:1493–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nygard O, Vollset SE, Refsum H, Brattstrom L, Ueland PM. Total homocysteine and cardiovascular disease. J Int Med. 1999;246:425–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selhub J. Homocysteine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:217–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC., Jr AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123:1939–51. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook RJ, Wagner C. Glycine N-methyltransferase is a folate binding protein of rat liver cytosol. Proc Natl Aca Sci USA. 1984;81:3631–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowling MJ, Schalinske KL. Retinoic acid and glucocorticoid treatment induce hepatic glycine N-methyltransferase and lower plasma homocysteine concentrations in rats and rat hepatoma cells. J Nutr. 2003;133:3392–98. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanghe KA, Garrow TA, Schalinske KL. Triiodothyronine treatment attenuates the induction of hepatic glycine N-methyltransferase by retinoic acid and elevates plasma homocysteine concentrations in rats. J Nutr. 2004;134:2913–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridgway ND, Vance DE. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase from rat liver. Met Enzymol. 1992;209:366–374. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)09045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vance DE, Pelech SL, Choy PC. CTP: Phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase from rat liver. Meth Enzymol. 1981;71:576–81. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)71070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Karaplis AC, Ackerman SL, Pogribny IP, Melnyk S, Lussier-Cacan S, Pai A, John S, Smith R, Bottiglieri T, Bagley P, Selhub J, Rudnicki MA, James SJ, Rozen R. Mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase exhibit hyperhomocysteinemia and decreased methylation capacity, with neuropathology and aortic lipid deposition. Hum Molec Genet. 2001;10:433–43. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Jhee KH, Hua X, DiBello PM, Jacobsen DW, Kruger WD. Modulation of cystathionine beta-synthase level regulates total serum homocysteine in mice. Circ Res. 2004;94:1318–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129182.46440.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Chen X, Tang B, Hua X, Klein-Szanto A, Kruger WD. Expression of mutant human cystathionine beta-synthase rescues neonatal lethality but not homocystinuria in a mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2201–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holm PI, Ueland PM, Kvalheim G, Lien EA. Determination of choline, betaine and dimethylglycine in plasma by a high-throughput method based on normal-phase chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2003;49:286–94. doi: 10.1373/49.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pogribny I, Yi P, James SI. A sensitive new method for rapid detection of abnormal methylation patterns in global DNA and within CpG islands. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1999;262:624–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrow TA. Choline. In: Zempeleni J, Rucker RB, McCormick DB, Suttie JW, editors. Handbook of vitamins. 4th. CRC Press; 2007. pp. 459–87. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stead LM, Brosnan JM, Brosnan ME, Vance DE, Jacobs RL. Is it time to reevaluate methyl balance in humans? AJCN. 2006;83:5–10. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noga AA, Stead LM, Zhao Y, Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT, Vance DE. Plasma homocysteine is regulated by phospholipid methylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5952–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walkey CJ, Donohue LR, Bronson R, Agellon LB, Vance DE. Disruption of the murine gene encoding phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12880–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walkey CJ, Yu L, Agellon LB, Vance DE. Biochemical and evolutionary significance of phospholipid methylation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27043–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noga AA, Vance DE. A gender-specific role for phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-derived phosphatidylcholine in the regulation of plasma high density and very low density lipoproteins in mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21851–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelstein JD, Martin JJ. Methionine metabolism in mammals. Distribution of homocysteine between competing pathways. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9508–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jencks DA, Mathews RG. Allosteric inhibition of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase by adenosylmethionine. Effects of adenosylmethionine and NADPH on the equilibrium between active and inactive forms of the enzyme and on the kinetics of approach to equilibrium. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2485–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu SC, Alvarez L, Huang ZZ, Chen L, An W, Corrales FJ, Avila MA, Kanel G, Mato JM. Methionine adenosyltransferase 1A knockout mice are predisposed to liver injury and exhibit increased expression of genes involved in proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(10):5560–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091016398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tateishi N, Hirasawa M, Higashi T, Sakamoto Y. The L-methionine-sparing effect of dietary glutathione in rats. J Nutr. 1982;112(12):2217–26. doi: 10.1093/jn/112.12.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prudova A, Bauman Z, Braun A, Vitvitsky V, Lu SC, Banerjee R. S-adenosylmethionine stabilizes cystathionine beta-synthase and modulates redox capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509531103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tateishi N, Higashi T, Naruse A, Hikita K, Sakamoto Y. Relative contributions of sulfur atoms of dietary cysteine and methionine to rat liver glutathione and proteins. J Biochem. 1981;90:1603–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitvitsky V, Dayal S, Stabler S, Zhou Y, Wang H, Lentz SR, Banerjee R. Perturbations in homocysteine-linked redox homeostasis in a murine model for hyperhomocysteinemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R39–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00036.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe M, Osada J, Aratani Y, Kluckman K, Reddick R, Malinow MR, Maeda N. Mice deficient in cystathionine beta-synthase: animal models for mild and severe homocyst(e)inemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1585–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:101–63. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warskulat U, Heller-Stilb B, Oermann E, Zilles K, Haas H, Lang F, Häussinger D. Phenotype of the taurine transporter knockout mouse. Methods Enzymol. 2007;428:439–58. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)28025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wojcik OP, Koenig KL, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Costa M, Chen Y. The potential protective effect of taurine on coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamori Y, Liu L, Ikeda K, Miura A, Mizushima S, Miki T, Nara Y, WHO-Cardiovascular Disease and Alimentary Comparison (CARDIAC) Study Group Distribution of twenty-four hour urinary taurine excretion and association with ischemic heart disease mortality in 24 populations of 16 countries: results from the WHO-CARDIAC study. Hypertens Res. 2001;4:453–7. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamori Y, Liu L, Mizushima S, Ikeda K, Nara Y, CARDIAC Study Group Male cardiovascular mortality and dietary markers in 25 population samples of 16 countries. J Hypertens. 2006;8:1499–505. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000239284.12691.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasouli ML, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, Park R, Aziz DC, Budoff MJ. Plasma homocysteine predicts progression of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steegers-Theunissen RP, Boers GH, Trijbels FJ, Eskes TK. Neural-tube defect and darangement of homocysteine metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:199–200. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101173240315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills JL, McPartlin JM, Kirke PN, Lee YJ, Conley MR, Weir DG, Scott JM. Homocysteine metabolism in pregnancies complicated by neural-tube defects. Lancet. 1995;345:148–51. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke R, Daly L, Robinson K, Naugheten E, Cahalane S, Fowler B, Graham I. Hyperhomocysteinemia: an independent risk factor for vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1149–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seshadri S, Beiser A, Selhub J, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Wolf PA. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:476–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wainfan E, Dizik M, Stender M, Christman JK. Rapid appearance of hypomethylated DNA in livers of rats fed cancer-promoting, methyl-deficient diets. Cancer Res. 1989;15:4094–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsitsiou E, Sibley CP, D'Souza SW, Catanescu O, Jacobsen DW, Glazier JD. Homocysteine transport by systems L, A and y+L across the microvillous plasma membrane of human placenta. J Physiol. 2009;587:4001–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heil SG, Lievers KJA, Boers GH, Verhoef P, den Heijer M, Trijbels FJM, Blom HJ. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT): Genomic sequencing and relevance to hyperhomocysteinemia and vascular disease in humans. Mol Gen Met. 2000;71:511–9. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morin I, Platt R, Weisberg I, Sabbaghian N, Wu Q, Garrow TA, Rozen R. Common variant in betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) and risk for spina bifida. Am J Med Gen. 2003;119A:172–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisberg IS, Park E, Ballman KV, Berger P, Nunn M, Suh DS, Breksa AP, Garrow TA, Rozen R. Investigations of a common genetic variant in betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) in coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2003;167:205–14. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fredriksen A, Meyer K, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, Grotmol T, Schneede J. Large-scale population-based metabolic phenotyping of thirteen genetic polymorphisms related to one-carbon metabolism. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(9):856–65. doi: 10.1002/humu.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ananth CV, Elsasser DA, Kinzler WL, Peltier MR, Getahun D, Leclerc D, Rozen RR, New Jersey Placental Abruption Study Investigators Polymorphisms in methionine synthase reductase and betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase genes: risk of placental abruption. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;1:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giusti B, Saracini C, Bolli P, Magi A, Martinelli I, Peyvandi F, Rasura M, Volpe M, Lotta LA, Rubattu S, Mannucci PM, Abbate R. Early-onset ischaemic stroke: Analysis of 58 polymorphisms in 17 genes involved in methionine metabolism. Thromb Haemost. 2010;2:104. doi: 10.1160/TH09-11-0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]