Abstract

A convergent synthesis of the C31-C52 bis-tetrahydropyran core of the natural product amphidinol 3 is reported. A common intermediate was synthesized from D-tartaric acid utilizing an asymmetric glycolate alkylation/ring-closing metathesis sequence to construct the THP rings. Differential elaboration of the common intermediate allowed the synthesis of two distinct coupling partners which were joined through a modified Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination to provide the bis-tetrahydropyran core.

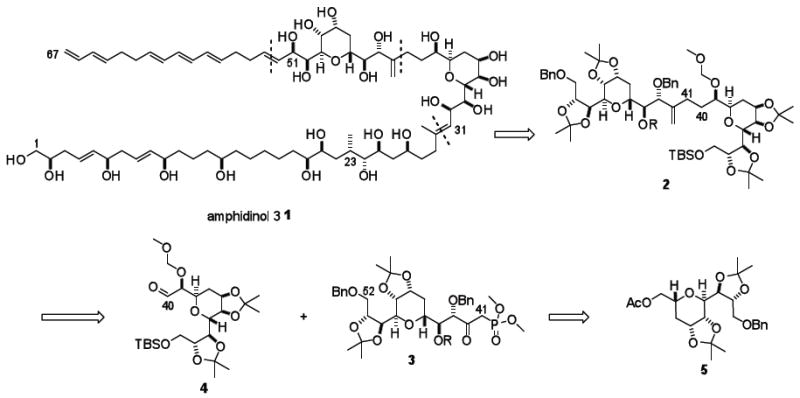

Amphidinol, isolated from Amphidinium klebsii, was discovered in 1991 by Yasumoto and coworkers and determined to be the first member of a new class of polyketide metabolites.1 The amphidinols, unlike polycyclic ethers isolated from other dinoflagellates, are mainly characterized by long carbon chains with multiple hydroxyl groups and polyolefins. Amphidinol 3 (1, Scheme 1) was discovered in 1996 from the same organism and is reported to have the greatest antifungal and hemolytic activity of any of the amphidinols reported to date.2 The 67-carbon backbone contains 25 stereocenters, a highly oxygenated bis-tetrahydropyran core (C31-C51), a heavily unsaturated region featuring a unique (E,E,E)-triene (C52-C67), and a polyol domain consisting of repeating 1,5-diol moieties (C1-C30).3 In 2008, Murata published a revised structure, in which the absolute configuration at C2 had been changed to R.4

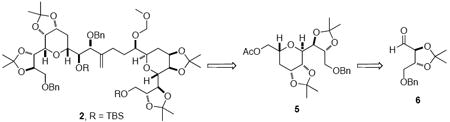

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis

Due to its biological activity and challenging structure, amphidinol 3 has garnered much attention from the synthetic community. While no total syntheses have been reported to date, fragment syntheses have been reported by several laboratories4-10 including contributions from Markó,6 Oishi,7 Paquette,8 Roush,9 and Rychnovsky10 toward the synthesis of the tetrahydropyran core.

Based on the retrosynthetic plan illustrated in Scheme 1, bis-tetrahydropyran core 2 was established as the initial target. Our strategy focused on exploitation of the symmetry of the C31-C39 and C44-C52 tetrahydropyran moieties to access the core bis-tetrahydropyran unit. A Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination would introduce the desired C40-41 bond as an enone which could be further elaborated. Tetrahydropyran 5 would be obtained utilizing the asymmetric glycolate alkylation-ring closing metathesis strategy developed in our laboratories.11

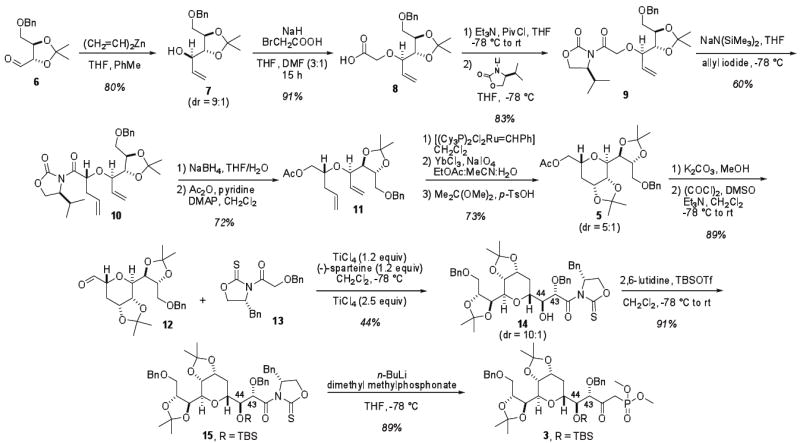

Synthesis of tetrahydropyran 5 is illustrated in Scheme 2. Known aldehyde 6 was accessed via d-tartaric acid, following a four step protocol (Scheme 2).12 Several conditions for the vinyl addition to aldehyde 6 were tested, and ultimately Felkin-Ahn controlled divinyl zinc addition was deteremined to deliver allylic alcohol 7 as a 9:1 ratio of inseparable diastereomers in 80% yield. Alkylation of alcohol 7 with bromoacetic acid afforded acid 8, which could be coupled with a valine-derived oxazolidinone to afford N-glycolyl oxazolidinone 9. At this point the two diastereomers could be readily separated by chromatography.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Tetrahydropyran 5 and Elaboration to β-ketophosphonate 3

Alkylation of the sodium enolate of 9 with allyl iodide introduced a key stereocenter with excellent diastereoselectivity (>95:5).11 Reductive removal of the auxiliary followed by protection of the resultant alcohol afforded diene 11. The alkylation could be performed on 20g scale and carried forward without purification to diene 11. From diene 11, a ring closing metathesis followed by a dihydroxylation would provide the requisite functionality of common intermediate 5.

Thus, direct exposure of the unpurified RCM product to sodium periodate followed by protection of the diol as an acetonide provided tetrahydropyran 5. As shown previously in the literature,13 addition of a Lewis acid decreased the amount of undesired over oxidation during dihydroxylation. Following this procedure, tetrahydropyran 5 could be obtained in up to 73% yield over three steps as a 5:1 mixture of diastereomers in multigram quantities. The selectivity of this sequence is comparable to other conditions explored for dihydroxylation and requires no chromatography between reactions. While the sequence could be performed with the primary alcohol unprotected, it was found that conversion of the primary alcohol to an acetate was required to facilitate separation of the diastereomers.

Having accessed tetrahydropyran 5, NOESY analysis revealed the desired trans ring fusion of the major product. This is in agreement with the expected Felkin addition of the divinyl zinc reagent, as well as the chiral auxiliary directed glycolate alkylation. 2D NMR analysis of the intermediate dihydropyran also supports the assignment of trans ring fusion. NOESY analysis was further employed to determine the structure of the major diastereomer obtained as a result of the dihydroxylation of the dihydropyran.

With common intermediate 5 in hand, our attention turned to the synthesis of the two coupling partners, β-ketophosphonate 3 and aldehyde 4. Synthesis of the C41-C52 tetrahydropyran coupling partner 3 was initiated by methanolysis of the acetate followed by Swern oxidation14 to access aldehyde 12 (Scheme 2). A glycolate anti aldol reaction15 between aldehyde 12 and N-glycolyl oxazolidinethione 13 introduced the C43 and C44 stereocenters as a 10:1 ratio of separable diastereomers in 44% yield. Varying the amount of Lewis acid used in the reaction in an attempt to increase the yield resulted in decomposition or decreased selectivities. Simple conversion of aldol adduct 14 to the desired coupling partner, β-ketophosphonate 3, was effected by protection of the alcohol as the TBS ether and direct displacement of the auxiliary with lithiated dimethyl methylphosphonate16 in 89% yield.

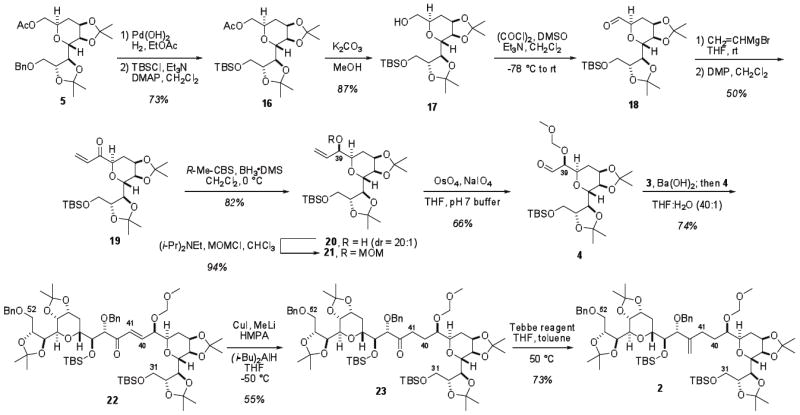

As a consequence of utilizing a common intermediate for the synthesis of both coupling partners, the two primary alcohols at C32 and C52 were both protected as benzyl ethers. However, differential protection of the two primary alcohols is required for the selective introduction of the polyene and polyol domains of amphidinol 3. To this end, before completing aldehyde 4 from common intermediate 5, the benzyl ether was cleaved and the resulting primary alcohol was protected with TBSCl to afford silyl ether 16 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Aldehyde 4 and Fragment Coupling

Removal of the acetate protecting group afforded alcohol 17, which was oxidized under Swern conditions. Various conditions were tested to introduce the C39 stereocenter, however a stereoselective vinyl addition remained elusive. The allylic alcohol was obtained at best in 86% yield as 3.5:1 mixture of diastereomers. Addition of nucleophiles to similar aldehydes has been previously reported with comparable results.8,10

In light of these difficulties, an alternative oxidation/stereoselective reduction sequence was pursued. Oxidation of the mixture of allylic alcohols derived from 18 with Dess-Martin periodinane17 provided enone 19, which upon CBS reduction18 afforded a single diastereomer of allylic alcohol 20. Advanced Mosher ester analysis19 was used to determine that the stereocenter at C39 was indeed the desired R configuration. With the stereochemistry confirmed, the allylic alcohol was then protected as a methoxymethyl ether to afford alkene 21. Several oxidation conditions to access aldehyde 4 were tested, including ozonolysis and oxidative cleavage with ruthenium chloride and sodium periodate. However, it was found that the Johnson-Lemieux oxidation utilized by Paquette8b provided the best yields of aldehyde 4.

With both coupling partners in hand, a modified Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction20 was pursued (Scheme 3). Initial attempts at union of the two fragments were carried out with the C39 hydroxyl group protected as a TBS ether instead of the MOM ether. It was found that the desired enone could be accessed in 52% yield, as an inconsequential mixture of E:Z isomers. Switching to the MOM ether saw an increase in yield and a decrease in reaction times. Treatment of β-ketophosphonate 3 with barium hydroxide followed by addition of aldehyde 4 afforded the desired enone 22 in 74% yield and granted access to the carbon backbone of the C31-C52 domain of amphidinol 3.

To complete the synthesis of the fragment, reduction of the C40-C41 alkene and formation of the 1,1-disubstituted alkene at C42 remained. A conjugate reduction was performed on enone 18 utilizing methyl copper and di-isobutylaluminum hydride21 to provide ketone 23. Subsequent transformation of ketone 23 to the bis- tetrahydropyran core 2 via a methylene Wittig reaction22 proved inconsistent and low yielding on a variety of similar systems. Treatment of ketone 23 with the Tebbe reagent23 at lower temperatures resulted in recovered starting material, even after prolonged reaction, however it was found that heating the reaction mixture for six hours resulted in formation of the 1,1-disubstituted alkene in 73% yield, providing the fully assembled bis-tetrahydropyran core 2 of amphidinol 3 1.

In conclusion, we report the convergent synthesis of the C31-C52 bis- tetrahydropyran core 2 of amphidinol 3 utilizing our asymmetric glycolate alkylation/ring-closing metathesis strategy. This approach allows for the synthesis of the C31-C40 and C41-C52 tetrahydropyrans from a common intermediate (5) that is accessible on multi-gram scale. Future work will focus on the synthesis of the polyol and polyene domains and their union with the bisTHP core.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM60567)) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental details and spectral data for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Satake M, Murata M, Yasumoto T, Fujita T, Naoki H. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9859–9861. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul GK, Matsumori N, Konoki K, Sasaki M, Murata M, Tachibana K. Harmful and Toxic Algal Blooms [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murata M, Matsuoka S, Matsumori N, Paul GK, Tachibana K. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:870. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oishi T, Kanemoto M, Swasono R, Matsumori N, Murata M. Org Lett. 2008;10:5203–5206. doi: 10.1021/ol802168r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) BouzBouz S, Cossy J. Org Lett. 2001;3:1451–1454. doi: 10.1021/ol0157095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cossy J, Tsuchiya T, Ferrie L, Reymond S, Kreuzer T, Colobert F, Jourdain P, Marko IE. Synlett. 2007:2286–2288. [Google Scholar]; (c) Colobert F, Kreuzer T, Cossy J, Reymond S, Tsuchiya T, Ferrie L, Marko IE, Jourdain P. Synlett. 2007:2351–2354. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubost C, Markó IE, Bryans J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:4005–4009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanemoto M, Murata M, Oishi T. J Org Chem. 2009;74:8810–8813. doi: 10.1021/jo901793f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Chang SK, Paquette LA. Org Lett. 2005;7:3111–3114. doi: 10.1021/ol0511833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bedore MW, Chang SK, Paquette LA. Org Lett. 2007;9:513–516. doi: 10.1021/ol062875+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Flamme EM, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2005;7:1411–1414. doi: 10.1021/ol050250q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hicks JD, Flamme EM, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2005;7:5509–5512. doi: 10.1021/ol052322j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hicks JD, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2008;10:681–684. doi: 10.1021/ol703042q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Huckins JR, de Vicente J, Rychnovsky SD. Org Lett. 2007;9:4757–4760. doi: 10.1021/ol7020934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huckins JR, de Vicente J, Rychnovsky SD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:7258–7262. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) de Vicente J, Betzemeier B, Rychnovsky SD. Org Lett. 2005;7:1853–1856. doi: 10.1021/ol050477l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crimmins MT, Emmitte KA. Org Lett. 1999;1:2029–2032. doi: 10.1021/ol991201e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukaiyama T, Suzuki K, Yamada T, Tabusa F. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:265. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beligny S, Eibauer S, Maechling S, Blechert S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1900–1903. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang SL, Swern D. J Org Chem. 1978;43:4537–4538. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crimmins MT, McDougall PJ. Org Lett. 2003;5:591–594. doi: 10.1021/ol034001i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delamarche I, Mosset P. J Org Chem. 1994;59:5453–5457. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dess DB, Martin JC. J Org Chem. 1983;48:4155–4156. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Corey EJ, Bakshi K, Shibata S. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5551–5553. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1986–2012. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<1986::AID-ANIE1986>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Dale JA, Mosher HS. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:512–519. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoye TR, Jefferson CS, Feng S. Nature Protocols. 2007;10:2451–2458. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarezibarra C, Arias S, Banon G, Fernandez MJ, Rodriguez M, Sinisterra VJ. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1987:1509–1511. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuda T, Hayashi T, Satomi H, Kawamoto T, Saegusea T. J Org Chem. 1986;51:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittig G, Haag W. Chem Ber. 1955;88:1654–1666. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tebbe FN, Parshall GW, Reddy GS. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:3611–3613. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.