Abstract

Activating mutations in members of the RAS oncogene family (KRAS, HRAS and NRAS) have been found in a variety of human malignancies, suggesting a dominant role in carcinogenesis. In colon cancers, KRAS mutations are common and clearly contribute to malignant progression. The frequency of NRAS mutations and their relationship to clinical, pathologic, and molecular features remains uncertain. We developed and validated a Pyroseqencing assay to detect NRAS mutations at codons 12, 13 and 61. Utilizing a collection of 225 colorectal cancers from two prospective cohort studies, we examined the relationship between NRAS mutations, clinical outcome, and other molecular features, including mutation of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA, microsatellite instability (MSI), and the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP). Finally, we examined whether NRAS mutation was associated with patient survival or prognosis. NRAS mutations were detected in 5 (2.2%) of the 225 colorectal cancers and tended to occur in left-sided cancers arising in women, but did not appear to be associated with any of the molecular features that were examined.

Keywords: NRAS, colon cancer, clinical outcome, sequencing, signal transduction

Introduction

The RAS proto-oncogenes (HRAS, KRAS and NRAS) encode a family of GDP/GTP-regulated switches that convey extracellular signals to regulate the growth and survival properties of cells.21 The four enzymes encoded by the three RAS genes are highly homologous to one another, sharing a high degree of identity over the first 90% of the proteins. The extreme carboxy-termini of the proteins constitute the hypervariable region, which diverges radically in primary sequence and undergoes post-translational modification that confers important differences in trafficking and intracellular localization.

RAS family members are frequently found in their mutated, oncogenic forms in human tumors. Mutant RAS proteins are constitutively active, owing to reduced intrinsic GTPase activity and insensitivity to GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). In total, activating mutations in the RAS genes occur in approximately 20% of all human cancers, mainly in codons 12, 13 or 61.10, 46 Mutations in KRAS account for about 85% of all RAS mutations in human tumors, NRAS for about 15%, and HRAS for less than 1%.12 Which particular RAS gene is mutated seems to be tumor specific; colonic, pancreatic and lung cancers have high frequencies of KRAS mutations. For example, we reported that KRAS gene mutations were present in 277 (36%) of 772 colorectal cancers analyzed.24, 36 NRAS mutations, by contrast, are common in myeloid leukemias and cutaneous melanomas.4, 39 Nevertheless, the frequency of NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer remains unclear.

GTP-bound RAS transmits its signal through a variety of downstream “effector” pathways, for example the RAF→MEK→ERK and PI3K→AKT cascades. Activating NRAS mutations occur in up to 30% of cutaneous melanoma cases and BRAF mutations also occur at a high frequency in these cancers. Recently, it has been reported that mutations in BRAF or NRAS are associated with decreased survival in patients with metastatic melanoma.16, 47 Interestingly, BRAF mutations are mutually exclusive with NRAS mutations in melanoma and with KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer.1, 9, 38, 44, 45, 50, 52 By contrast, mutations in PIK3CA (which encodes the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K) tend to co-exist with KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer.22, 48 The patterns of mutational co-occurrence suggest that each RAS effector plays a different role in tumor development. In this respect, understanding the genetic context in which NRAS mutations arise is important.

In this study, we used Pyrosequencing to identify NRAS mutations at codons 12, 13 and 61, the mutational hotspots for all of the RAS genes, in a set of 225 colorectal cancers. We examined the relationship between NRAS mutations and other molecular, pathologic, and clinical features, including mutations in KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA, microsatellite instability (MSI), CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) status, and patient survival.

Materials and Methods

Tissue specimens

Experimental samples were identified by searching the databases of two large prospective cohort studies: the Nurses' Health Study (N = 121,700 women followed since 1976) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (N = 51,500 men followed since 1986).14 A subset of the cohort participants developed colorectal cancer during prospective follow-up. Previous studies on the Nurses' Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study have described baseline characteristics of cohort participants and incident colorectal cancer cases and confirmed that our colorectal cancers were a good representative of a population-based sample.7, 14 We collected paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from hospitals where cohort participants with colorectal cancers had undergone resections of primary tumors. On the basis of availability of tissue materials and assay results, a total of 225 colorectal cancers were included in this study. Among our cohort studies, there was no significant difference in demographic features between cases with tissue available and those without available tissue.6 Hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections were examined by a pathologist (S.O.) unaware of clinical or other laboratory data.29 The tumor grade was categorized as low (≥50% gland formation) vs. high (<50% gland formation). The presence and extent of extracellular mucin and signet ring cells were recorded. Although many of the cases have been previously characterized for the status of CIMP, MSI, KRAS, BRAF, and p53,29 we have not examined NRAS mutations in our specimens. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Tissue collection and analyses were approved by the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard School of Public Health Institutional Review Boards.

Genomic DNA extraction and whole genome amplification

Genomic DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections using QIAmp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).28 Normal DNA was obtained from colonic tissue at resection margins. Whole genome amplification (WGA) of genomic DNA was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using random 15-mer primers.11, 28 Previous studies showed that WGA did not significantly affect downstream genetic analysis.3, 13

Pyrosequencing for NRAS

The primers for PCR and Pyrosequencing were purchased from EpigenDx inc. (EpigenDx, Worcester, MA), and PCR was conducted according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Each PCR mix contained 3 pmol of forward primer, 0.3 pmol of reverse primer, 2.7 pmol of Universal primer, 200 μmol each of dNTPs, 3.0 mmol MgCl2, 1xPCR buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), 0.75 U of HotStar Taq polymerase (Qiagen), and 1 μl of template WGA product in a total volume of 30 μl. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturing at 95°C for 15 minutes; 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds; and final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. The PCR products (each 10 μl) were sequenced using the Pyrosequencing PSQ96 HS System (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The nucleotide dispensation orders were: codon 12 - ACT GAC TAC GAC T, codon 13 - CAT GAC TAC TGA CTG, codon 61 - ACG TCT AGC AGT. To increase sensitivity, we designed a different Pyrosequencing primer for codon 13: 5′-GTGGTGGTTGGAGCAGGTG-3′. The use of three sequencing primers served as a quality control measure, because mutations in codon 13 are detected by at least two primers. To confirm the results, we repeated PCR-Pyrosequencing, with laboratory staff unaware of the previous results, using unique nucleotide dispensation orders and at a different facility (EpigenDx): codon 12 and 13 - TCG ATG CTA GTG TGC AGC G, codon 61 - CAT CGA TCA G.

Sanger sequencing analysis for NRAS

The mutational status of NRAS was confirmed by direct sequencing of PCR products generated using the following primer pairs: exon 2, 5′-ACGTTGGATGCAACAGGTTCTTGCTGGTGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACGTTGGATGgagagacaggatcaggtcagc-3′ (reverse); exon 3, 5′-ACGTTGGATGTGGTGAAACCTGTTTGTTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACGTTGGATGcctttcagagaaaataatgctcct-3′ (reverse). PCR was performed in a volume of 20 μl, containing 1 unit of Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 4 nmol of dNTPs (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10 pmol of forward and reverse primers, 40 nmol of MgCl2 and 40 ng of DNA. Thermocycling was performed at 95 °C for 8 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min, and one last cycle of 72 °C for 3 min. The resulting PCR products were treated using 1 unit of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (USB, Cleveland, OH) and 5 units of exonuclease I (USB, Cleveland, OH) at 37°C for 20 minutes followed by 80°C for 15 minutes, and tested for the presence of mutations by bi-directional Sanger sequencing using the original PCR primers and the BigDye Terminator V1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer′s recommendations. Tumor and control human genomic DNA (Promega, Madison, WI) sequences were compared using the AB Sequencing Analysis Software v5.2 (Applied Biosystems).

PCR and Pyrosequencing for KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA, and microsatellite analyses

PCR and Pyrosequencing targeted for KRAS codon 12 and 13,28 BRAF codon 600,30 and PIK3CA exons 9 and 20 were performed.24 Microsatellite instability (MSI) status was determined using D2S123, D5S346, D17S250, BAT25, BAT26, BAT40, D18S55, D18S56, D18S67 and D18S487.26 MSI-high was defined as the presence of instability in ≥30% of the markers, MSI-low as instability in 1-29% of the markers, and microsatellite stability (MSS) as the absence of instability. For 18q loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis using microsatellite markers (D18S55, D18S56, D18S67, and D18S487), LOH at each locus was defined as ≥40% reduction of one of two allele peaks in tumor DNA relative to normal DNA.31 Overall 18q LOH positivity was defined as the presence of any marker with LOH, and 18q LOH negativity as the presence of ≥2 informative markers and the absence of LOH.

Real-time PCR to measure CpG island methylation and Pyrosequencing to measure LINE-1 methylation

Bisulfite DNA treatment and real-time PCR (MethyLight) assays were validated and performed.27 We quantified methylation at 8 CIMP-specific CpG islands [CACNA1G, CDKN2A (p16), CRABP1, IGF2, MLH1, NEUROG1, RUNX3 and SOCS1].26, 29 CIMP-high was defined as ≥6/8 methylated promoters using the 8-marker CIMP panel, CIMP-low as 1/8-5/8 methylated promoters and CIMP-0 as 0/8 methylated promoters, according to the previously established criteria.29 We also quantified methylation at 8 other loci (CHFR, HIC1, IGFBP3, MGMT, MINT1, MINT31, p14, and WRN).22, 36 The percentage of methylated reference (PMR) at a specific locus was calculated as previously described.27 LINE-1 methylation level was measured by Pyrosequencing.32

Immunohistochemistry

We constructed tissue microarrays.6 Methods of immunohistochemistry were previously described as follows: cyclin D1,23 β-catenin,18 p21, p27, p53,33 fatty acid synthase (FASN) and COX-2.25 All immunohistochemically-stained slides for each marker were interpreted by one of the investigators (p53, p21, p27, COX-2 and FASN by S.O.; cyclin D1 and β-catenin by K.N.) unaware of other data. A random sample of 108-402 tumors were re-examined by a second observer (p21, p27 and cyclin D1 by K.S.; p53, FASN by K.N.; β-catenin by S.O.; COX-2 by R. Dehari, Kanagawa Cancer Center, Japan) unaware of other data. The concordance between the two observers (all p<0.0001) was: 0.83 (κ=0.64, N=160) for cyclin D1; 0.87 (κ=0.75, N=118) for p53; 0.83 (κ=0.62, N=179) for p21; 0.94 (κ=0.60, N=114) for p27; 0.83 (κ=0.65, N=402) for β-catenin; 0.92 (κ=0.62, N=108) for COX-2; 0.93 (κ=0.57, N=246) for FASN, indicating good to substantial agreement.

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test was performed to assess associations between categorical data, using the SAS program (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All P values were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. A correction of multiple hypothesis testing was not attempted due to a limited power.

Results

NRAS mutation in colorectal cancer

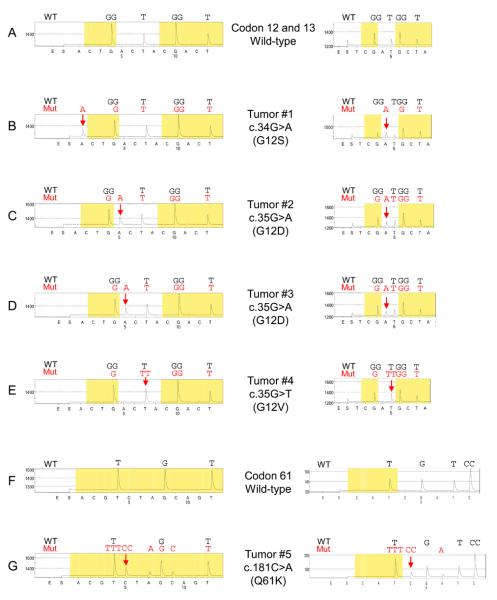

We used Pyrosequencing to determine the frequency of NRAS codon 12, 13 and 61 mutations in sporadic colorectal cancers. The normal amino acid at codons 12 and 13 of the NRAS gene is glycine (GGT) and the normal amino acid at codon 61 is glutamine (CAA). In this study of 225 colorectal cancers, 5 cases (2.2%) harbored NRAS activating mutations (Figure 1). These mutations were confirmed by different nucleotide dispensation orders for Pyrosequencing and by Sanger sequencing. The activating mutations found in the NRAS gene were c.34G>A (p.G12S), c.35G>A (p.G12D) and c.35G>T (p.G12V) in codon 12 and c.181C>A (p.Q61K) in codon 61. No codon 13 mutations were detected. These NRAS mutations have been described in other cancers (the Sanger Institute COSMIC database; www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/).

Figure 1.

NRAS Pyrosequencing assay. (A) Wild-type codon 12 and 13. (B) The c.34G>A (p.G12S) mutation (arrow). (C) (D) The c.35G>A (p.G12D) mutation (arrow). (E) The c.35G>T (p.G12V) mutation (arrow). (F) Wild-type codon 61. (G) The c.181C>A (p.Q61K) mutation (arrow) causes a shift in reading frame and results in new peaks at A and C (arrowhead), which serves as quality assurance. Mut, mutant; WT, wild-type.

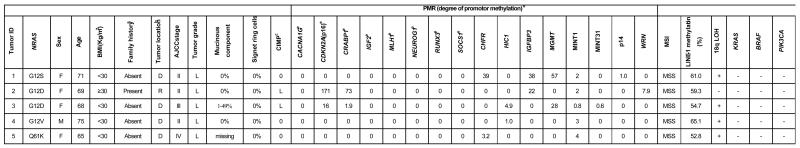

NRAS mutation and clinical, pathologic prognostic and molecular features

We examined genetic and epigenetic features as well as clinical outcome of 225 colorectal cancer cases according to NRAS mutation status (Table 1). A distribution of various molecular features detected in our colorectal cancers was essentially in agreement with the previous studies.2, 19, 22, 34, 35, 37 Table 2 shows clinical, pathologic and molecular features of colorectal cancers with NRAS mutations. NRAS mutations were mutually exclusive with mutations in BRAF, KRAS and PIK3CA, although the sample size was limited. All of the cancers with NRAS mutations were located in the distal (left-side) colon and 4/5 arose in female patients. Nevertheless, due to the low frequency of NRAS mutation, none of those relations was statistically significant. There was no apparent association between the NRAS mutations and any of the other clinical or pathological features examined (Table 1). Likewise, there was no significant association between NRAS mutation and any of the other tumoral markers in Table 1, or to β-catenin, p53, p21, p27, cyclin D1, COX-2 and FASN (data not shown). In addition, no significant effect of NRAS mutation on patient survival was noted (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of colorectal cancer patients according to NRAS mutation status.

| Clinical, pathologic and molecular feature | Total No. | Wild-type NRAS | Mutant NRAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | 225 | 220 | 5 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 108 (48%) | 107 (49%) | 1 (20%) |

| Female | 117 (51%) | 113 (51%) | 4 (80%) |

| Mean age ± SD | 67.4 ± 8.7 | 67.4 ± 8.8 | 69.9 ± 3.6 |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | |||

| <30 | 172 (82%) | 168 (82%) | 4 (80%) |

| ≥30 | 38 (18%) | 37 (18%) | 1 (20%) |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | |||

| Absent | 170 (76%) | 166 (76%) | 4 (80%) |

| Present | 55 (24%) | 54 (24%) | 1 (20%) |

| Tumor location | |||

| Proximal colon (cecum to transverse) | 98 (46%) | 98 (47%) | 0 |

| Distal colon (splenic flexure to sigmoid) | 71 (33%) | 67 (32%) | 4 (80%) |

| Rectum | 46 (21%) | 45 (21%) | 1 (20%) |

| AJCC stage | |||

| I | 59 (26%) | 59 (26%) | 0 |

| II | 53 (24%) | 50 (24%) | 3 (60%) |

| III | 56 (25%) | 55 (25%) | 1 (20%) |

| IV | 33 (15%) | 32 (15%) | 1 (20%) |

| Unknown | 24 (10%) | 24 (10%) | 0 |

| Tumor grade | |||

| Low | 187 (89%) | 182 (88%) | 5 (100%) |

| High | 24 (11%) | 24 (12%) | 0 |

| Mucinous component | |||

| 0% | 105 (57%) | 102 (57%) | 3 (75%) |

| ≥1% | 47 (43%) | 78 (43%) | 1 (25%) |

| Signet ring cells | |||

| 0% | 152 (92%) | 148 (92%) | 5 (100%) |

| ≥1% | 13 (7.9%) | 13 (8.0%) | 0 |

| CIMP | |||

| CIMP-low/0 | 174 (85%) | 169 (85%) | 5 (100%) |

| CIMP-high | 30 (15%) | 30 (15%) | 0 |

| MSI | |||

| MSI-low/MSS | 184 (83%) | 179 (83%) | 5 (100%) |

| MSI-high | 37 (17%) | 37 (17%) | 0 |

| 18q loss of heterozygosity (LOH) | |||

| (−) | 65 (42%) | 64 (43%) | 1 (20%) |

| (+) | 88 (58%) | 84 (57%) | 4 (80%) |

| Mean LINE-1 methylation (%) ± SD | 61.5 ± 9.3 | 61.6 ± 9.3 | 58.6 ± 5.0 |

| KRAS mutation | |||

| (−) | 132 (59%) | 127 (58%) | 5 (100%) |

| (+) | 92 (41%) | 92 (42%) | 0 |

| BRAF mutation | |||

| (−) | 189 (86%) | 184 (86%) | 5 (100%) |

| (+) | 30 (14%) | 30 (14%) | 0 |

| PIK3CA mutation | |||

| (−) | 184 (89%) | 179 (89%) | 5 (100%) |

| (+) | 23 (11%) | 23 (11%) | 0 |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; SD, standard deviation

Table 2.

Characteristics of colorectal cancers with NRAS mutations

|

Family history is positive when any first-degree relative has been affected with colorectal cancer.

D, distal colon (splenic flexure to sigmoid): R, rectum.

CIMP status; L, CIMP-low; 0, CIMP-0.

PMR (percentage of methylated reference; methylation index).

8 markers in the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)-specific marker panel.

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; LOH loss of heterozygosity

Discussion

We conducted this study to examine the frequency of NRAS mutation in relation to various genetic and epigenetic alterations in colorectal cancer. The RAS pathway plays an important role in the development of various cancers,17, 20, 43 and frequent activating mutations in the KRAS oncogene have been identified in colorectal cancer.28 Nevertheless, there are only a few reports on NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer and none of these studies correlated RAS mutations with other molecular events. 40, 49 We developed a Pyrosequencing assay to detect NRAS mutations because this methodology has been shown to be applicable to paraffin-embedded tumors and is more sensitive than Sanger dideoxy sequencing in KRAS mutation analysis.28 We found that NRAS mutation in colorectal cancer was rare (2.2%). This observation is consistent with publicly available cancer genome sequencing data from the Sanger Institute COSMIC database (www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/), which lists NRAS mutation frequency at approximately 3% in colon cancer.

Our resource of a population-based sample of colorectal cancer (relatively unbiased samples set compared with retrospective or single-hospital-based samples) derived from two prospective cohorts has enabled us to precisely estimate the frequency of specific molecular events (such as KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutations, CIMP etc.) and to correlate mutations with clinical and pathological features of colon cancer. We detected NRAS mutations in only 5 of 225 colon caners using Pyrosequencing (Figure 1). Because of the low frequency, NRAS mutation was not significantly associated with any clinical or pathologic features or with patient survival. Nevertheless, there was a trend towards NRAS mutations in left-sided MSS tumors that arise in females.

Mutational activation of RAS via a point mutation at codon 12, 13 or 61 is well characterized as a marker for progression of normal or benign cells toward malignancy.41, 42 Mutant RAS oncoproteins have decreased GTPase activity, essentially locking them into an activated state, and GTP-bound RAS transmits strong downstream signals that alter normal cellular functions.5 Nevertheless, different cancers select for mutations in different RAS family members, suggesting that the family members exhibit cell type-specific expression patterns or functions. NRAS is, perhaps, best characterized in leukemia and melanoma, where mutations are relatively common; NRAS mutations occur in 30% of melanomas and are mutually exclusive with mutations in BRAF, suggesting that these two events may be functionally equivalent. Unlike colon cancers, KRAS mutations are rare in melanomas.

Little is known regarding the impact of NRAS mutation in colorectal cancer. Some studies have shown that NRAS mutations seem to arise at a later stage in the development of malignancy, unlike KRAS mutations, which arise early.8, 49 Recent studies utilizing mouse models have demonstrated clear phenotypic differences between mutant KRAS and NRAS in colon cancer.15 Activated KRAS has a unique ability to promote tumor proliferation and to suppress differentiation, while activated NRAS suppressed apoptosis in a developing tumor. These data suggest that KRAS and NRAS mutations arise in response to unique selective pressures. KRAS mutations have recently been shown to arise under conditions of low glucose availability.51 The data from animal studies suggest that NRAS mutations might arise under conditions of chronic apoptotic stress.

Although the results of our study do not reach statistical significance, the trends in the data may provide insight into NRAS-mutant colorectal cancers. For example, our data indicate that NRAS mutations are found in left-sided MSS cancers. The mutational pattern is similar to that of KRAS, but entirely distinct from BRAF, which is mutated predominantly in right-sided CIMP-high cancers.22, 24 Thus, while NRAS and BRAF may play a similar role in melanoma progression, they appear to play distinct roles in colon cancer progression.

In conclusion, our cohort study shows that the frequency of NRAS activating mutations in colorectal cancers is low. Additional studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the oncogenic properties of the RAS oncogenes in colorectal cancers.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the U.S. National Institute of Health (P01 CA87969 to S. Hankinson, P01 CA55075 to W. Willett, P50 CA127003 to C.S.F., K07 CA122826 to S.O., K01 CA118425 to K.M.H.); the Bennett Family Fund; the Entertainment Industry Foundation National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance. K.N. was supported by a fellowship grant from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCI or NIH. Funding agencies did not have any role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the decision to submit the manuscript for publication; or the writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

NI, YB and KN contributed equally. CSF, KMH and SO are co-senior authors.

References

- 1.Banerji U, Affolter A, Judson I, et al. BRAF and NRAS mutations in melanoma: potential relationships to clinical response to HSP90 inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:737–739. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barault L, Veyrie N, Jooste V, et al. Mutations in the RAS-MAPK, PI(3)K (phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase) signaling network correlate with poor survival in a population-based series of colon cancers. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2255–2259. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell SL, Khosravi-Far R, Rossman KL, et al. Increasing complexity of Ras signaling. Oncogene. 1998;17:1395–1413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of COX-2. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2131–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses' Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:388–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demunter A, Stas M, Degreef H, et al. Analysis of N- and K-ras mutations in the distinctive tumor progression phases of melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1483–1489. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhomen N, Marais R. New insight into BRAF mutations in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz-Flores E, Shannon K. Targeting oncogenic Ras. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1989–1992. doi: 10.1101/gad.1587907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietmaier W, Hartmann A, Wallinger S, et al. Multiple mutation analyses in single tumor cells with improved whole genome amplification. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:83–95. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, et al. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E32. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:451–459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haigis KM, Kendall KR, Wang Y, et al. Differential effects of oncogenic K-Ras and N-Ras on proliferation, differentiation and tumor progression in the colon. Nat Genet. 2008;40:600–608. doi: 10.1038/ngXXXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaiswal BS, Janakiraman V, Kljavin NM, et al. Combined targeting of BRAF and CRAF or BRAF and PI3K effector pathways is required for efficacy in NRAS mutant tumors. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki T, Nosho K, Ohnishi M, et al. Correlation of beta-catenin localization with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer. Neoplasia. 2007;9:569–577. doi: 10.1593/neo.07334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearney KE, Pretlow TG, Pretlow TP. Increased expression of fatty acid synthase in human aberrant crypt foci: possible target for colorectal cancer prevention. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:249–252. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lea IA, Jackson MA, Dunnick JK. Genetic Pathways to Colorectal Cancer. Mutat Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nosho K, Irahara N, Shima K, et al. Comprehensive biostatistical analysis of CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer using a large population-based sample. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nosho K, Kawasaki T, Chan AT, et al. Cyclin D1 is frequently overexpressed in microsatellite unstable colorectal cancer, independent of CpG island methylator phenotype. Histopathology. 2008;53:588–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nosho K, Kawasaki T, Ohnishi M, et al. PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer: relationship with genetic and epigenetic alterations. Neoplasia. 2008;10:534–541. doi: 10.1593/neo.08336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogino S, Brahmandam M, Cantor M, et al. Distinct molecular features of colorectal carcinoma with signet ring cell component and colorectal carcinoma with mucinous component. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:59–68. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogino S, Cantor M, Kawasaki T, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) of colorectal cancer is best characterised by quantitative DNA methylation analysis and prospective cohort studies. Gut. 2006;55:1000–1006. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, et al. Precision and performance characteristics of bisulfite conversion and real-time PCR (MethyLight) for quantitative DNA methylation analysis. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:209–217. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, et al. Sensitive sequencing method for KRAS mutation detection by Pyrosequencing. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:413–421. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60571-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, et al. Evaluation of markers for CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer by a large population-based sample. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:305–314. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) in colorectal cancer: possible associations with male sex and KRAS mutations. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:582–588. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, et al. 18q loss of heterozygosity in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer is correlated with CpG island methylator phenotype-negative (CIMP-0) and inversely with CIMP-low and CIMP-high. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Nosho K, et al. LINE-1 hypomethylation is inversely associated with microsatellite instability and CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2767–2773. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogino S, Meyerhardt JA, Cantor M, et al. Molecular alterations in tumors and response to combination chemotherapy with gefitinib for advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6650–6656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, et al. A cohort study of cyclin d1 expression and prognosis in 602 colon cancer cases. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4431–4438. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut. 2009;58:90–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.155473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, et al. PIK3CA mutation is associated with poor prognosis among patients with curatively resected colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1477–1484. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogino S, Shima K, Nosho K, et al. A cohort study of p27 localization in colon cancer, body mass index, and patient survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1849–1858. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ollikainen M, Gylling A, Puputti M, et al. Patterns of PIK3CA alterations in familial colorectal and endometrial carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:915–920. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omholt K, Platz A, Kanter L, et al. NRAS and BRAF mutations arise early during melanoma pathogenesis and are preserved throughout tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6483–6488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oudejans JJ, Slebos RJ, Zoetmulder FA, et al. Differential activation of ras genes by point mutation in human colon cancer with metastases to either lung or liver. Int J Cancer. 1991;49:875–879. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parikh C, Ren R. Mouse model for NRAS-induced leukemogenesis. Methods Enzymol. 2008;439:15–24. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)00402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parikh C, Subrahmanyam R, Ren R. Oncogenic NRAS, KRAS, and HRAS exhibit different leukemogenic potentials in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7139–7146. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinlan MP, Settleman J. Isoform-specific ras functions in development and cancer. Future Oncol. 2009;5:105–116. doi: 10.2217/14796694.5.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossi DJ, Weissman IL. Pten, tumorigenesis, and stem cell self-renewal. Cell. 2006;125:229–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samuels Y, Diaz LA, Jr., Schmidt-Kittler O, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ugurel S, Thirumaran RK, Bloethner S, et al. B-RAF and N-RAS mutations are preserved during short time in vitro propagation and differentially impact prognosis. PLoS One. 2007;2:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Velho S, Oliveira C, Ferreira A, et al. The prevalence of PIK3CA mutations in gastric and colon cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1649–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004;116:855–867. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yun J, Rago C, Cheong I, et al. Glucose Deprivation Contributes to the Development of KRAS Pathway Mutations in Tumor Cells. Science. 2009 doi: 10.1126/science.1174229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Helical domain and kinase domain mutations in p110alpha of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induce gain of function by different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2652–2657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712169105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]