Abstract

The interplay of neuroendocrine processes and gonadal function is exquisitely expressed during aging. In females, loss of ovarian function results in decreased circulating estradiol. As a result, estrogen dependent endocrine and behavioral responses decline, including impaired cognitive function reflecting the impact of declining estrogen on the hippocampus circuits, and decreased metabolic endocrine function. Concurrently, age-related changes in neuroendocrine response also contribute to the declining reproductive function. Our session considered key mechanisms in reproductive aging including the roles of ovarian function(Finch and Holmes) and the hypothalamic median eminence (Gore and colleagues) with an associated age-related cognitive decline that accompanies estrogen loss (Morrison and colleagues). Effects of smoking, obesity, and insulin resistance (Sowers and colleagues) impact the timing of the peri-menopause transition in women. Animal models provide excellent insights into conserved mechanisms and key overarching events that bring about endocrine and behavioral aging. Environmental factors are key triggers in timing endocrine aging with implications for eventual disease. Session presentations will be considered in the context of the broader topic of indices and predictors of aging-related change.

Keywords: neuroendocrine aging, negligent senescence, peri-menopause transition, healthy aging, insulin resistance, environmental factors

The timing of the age-related decline in reproduction function depends on a complex interplay of interacting changes at all levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonad (HPG) axis. In women, the peri-menopause transition may be relatively short or persist over many years with few clues as to the triggers for the timing of these changes in an individual. Despite vast differences in lifetime reproductive strategies across vertebrates, there are interesting commonalities in aging processes. Comparison of patterns in reproductive aging across vertebrate species reveal that key elements and the underlying mechanisms that bring about age-related changes are conserved; that is, the fundamental sequence and elements of events that occur during aging are common across vertebrates. Comparative animal models and data from non-human primates provide valuable insights into the functional changes that accompany the age-related reproductive decline and how these changes relate to aging of other physiological and endocrine systems. Furthermore, there are interesting examples of species that have surprisingly long lifespan compared with those that are short-lived; for example seabirds and tortoises have an extraordinarily long lifespan, while Japanese quail and mice are relatively short-lived. Early exposure to external environmental factors as well as lifetime habits, such as diet and disease, are likely critical triggers in the timing of reproductive decline and eventual senescence. These environmental factors may be proximate, such as smoking or lifestyle, or they may be inadvertent, such as exposure to contaminants. For example, recent data strongly support the role of environmental chemicals that have the ability to mimic hormones as contributors to age-related demise in physiological function and neural disease.20 Taken together, there are complex interactions directing the progression of aging processes, with the onset and time course of events potentially modified by environmental factors according to the target and mechanisms of effects associated with exposure.

Progression of endocrine events during aging

Age-related changes in the reproductive endocrine axis (HPG axis) follow individually dictated timelines. That is, a population and species have general characteristics in the timing and sequence of age-related decline in endocrine function; an individual may experience earlier, average, or later onset in the aging process. In general, males experience declining reproductive function in a gradual manner with significant eduction in circulating androgen levels relatively late in life. Reduction in libido and other age-related changes in metabolic endocrine and physiology gradually emerge, often preceding loss of spermatogenesis. These outcomes may be exacerbated by the use of pharmaceuticals, especially those that impact neural systems that also regulate endocrine and behavioral components of reproduction. Females experience a sharper decline in reproductive function, due to a combination of progressively erratic ovulations and eventual ovarian failure. The loss of ovarian function is accompanied by the loss of cycles in reproductive hormones. There is remarkable similarity in the pattern of ovarian decline across a variety of species which provides a powerful comparison to understand basic mechanisms in aging processes (see Finch and Holmes, this issue). And although there is controversy regarding the extent and even occurrence of post reproductive lifespan, studies, especially in long lived species, provide supporting data for life following cessation in reproductive function. For example, if there is a social structure that incorporates post-reproductive roles for individuals in caring for young (grandmother hypothesis), then the function and presence of post-reproductive individuals have been well documented. Despite the discussion about post-reproductive lifespan, the events leading to the ultimate cessation of reproduction have been the source of extensive research, especially in rodent models. These studies and comparative data collected from primates and non-mammalian models point to the critical role of ovarian cycling and accompanying ovarian steroidogenesis in the maintenance of female reproduction. However, assessing the status of ovarian function during the aging process has proven difficult. A set of tests terms ovarian reserve tests has proven to be good indicators of ovarian follicular content and response.4 A strong positive response to an ovarian reserve test can serve as a key indicator for continued ovarian cycling, fertility, and potential success with the use of assisted reproductive technologies. The responsiveness of ovarian follicles, especially related to steroid production diminishes during the peri-menopause transition leading to reduced estradiol production and lower circulating estradiol levels, which in turn translate into blunted stimulation of the pre-ovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge. This ‘domino effect’ continues; the consequence of insufficient LH release is failure to ovulate, at least for some cycles. Ovulation becomes increasingly erratic accompanied by loss of progesterone production, which would have been produced post-ovulation. This general sequence of events occurs across females of various species and vertebrate classes13,18. Comparison of ovarian function in short- and long-lived species affords the opportunity to study reproductive aging processes over differing time scales. As such, aging progresses more slowly in long lived organisms and there are coincident differences in lifetime reproductive strategies. These comparisons also provide a compelling case for insights from studies in the comparative biology of aging.

In primates, menopause is the signal of the complete collapse of ovarian function. The demise of ovarian function is accompanied by the loss of circulating estradiol and progesterone, and increased pituitary gonadotropin levels. The peri-menopause transition may be quite extended, with declining fertility as early as the 30s and certainly in the 40s for women. Markers of the peri-menopause transition have become much more precise at giving information about individual status relative to this transition. Decreasing ovarian follicular reserve is particularly revealing because it is associated with decreased steroid synthesis, reduced inhibin β and anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) production.1–6 As discussed above, decreased ovarian function has several ramifications including reduced steroid feedback and signaling to hypothalamic areas that modulate gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) production and release. Concurrently, there is altered hypothalamic signaling to the pituitary gland against a background of reduced ovarian feedback, resulting in elevated follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and a transient increase in luteinizing hormone (LH). As ovarian reserve decreases, ovulation becomes more sporadic with a coincident increase in variability in cycle length. During this transition, circulating steroids shift from cycle associated peak estradiol in the follicular phase and peak progesterone levels in the luteal phase, to unopposed elevated estradiol owing to the absence of ovulation. The unopposed estradiol production associated with stimulation of follicular development is exacerbated by increasing FSH and LH levels in response to diminished negative feedback due to loss of progesterone and inhibin β. This cascade is soon followed by ovarian failure and loss of estradiol as well as progesterone. These changes in the menstrual cycle of primates are shown in Figure 1, which shows cycles in the rhesus macaque. The figures present data from our studies which illustrate these shifting hormone levels during the peri-menopause transition in the rhesus macaque in which regular cycles (Figure 1A) transition to irregular cycles with intermittent ovulation (Figure 1B) and finally to menopause with loss of circulating steroid hormones (Figure 1C).3,4,7,8 It is interesting to note that a phase of unopposed high circulating estrogen prior to ovarian failure also occurs in rodent models, in which females enter a phase of constant estrus associated with high levels of estradiol. However, this phase may persist for a longer period in rodents compared with primates.

Figure 1.

The menstrual cycle in the rhesus macaque female (data from dissertation research by Julie Wu, Ph.D.). Figures 1a, b, and c show the progression of hormone cycles over the reproductive lifespan of the female with a transition from (a) regular cycles to (b) irregular and anovulatory cycles and (c) collapse of ovarian function in the post menopausal female (from reference 3).

Although transient, these changes in circulating steroid hormone levels represent a roller coaster in hormonal background that have unclear consequences for hormone dependent systems, including brain regions responsible for cognition. As discussed by Morrison and colleagues (see this volume), estradiol has neuroprotective actions as well as stimulates hippocampal neuronal spines; whereas, loss of estradiol is accompanied by diminished cognitive function and altered neuroplasticity.9,10 Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) remains controversial for post menopausal women. In some women, HRT effectively blunts the effects of these dramatic changes in circulating steroid hormone levels including diminished cognitive function. Risks associated with the use of HRT have led to additional studies which seek to resolve the controversy about the merits of HRT, including the use of native hormones versus conjugated steroids.10

Triggers that signal and direct the timing of the peri-menopause transition in an individual are modulated by both internal and external factors. Because these are complex interacting factors, studies in non-human primates provide the most precise insights into the complexities of these interactions for biomedical applications and human populations.6–8,11 Moreover, the applicability of a variety of possible interventions have been a rich source of options for aging populations as we seek to diminish the effects of age-related maladies and disease. Some of the most effective interventions have included dietary paradigms, such as caloric restriction and healthy diets.8,11,13 Conversely, as reviewed by Sowers and colleagues (see this volume), factors such as smoking, obesity, and insulin resistance can have adverse effects on the HPG axis, ultimately resulting in earlier and perhaps premature occurrence of the final cycle. It is also clear that there is a great deal of individual variation in both the response to these factors and the extent to which an individual may be affected. This means that the timing of menopause may be premature if the individual’s ovarian function is severely impaired. However, in the event that ovarian processes are muted by environmental factors, there may be a less dramatic outcome, meaning that there may not be premature menopause but there may be more irregular cycling or prolonged peri-menopause transition. Further, physiological status and disease also contribute to the overall health of the individual, making it difficult to discern clear causal factors; the mechanisms by which this interaction may occur remain complex and multifactor. Although the adrenal axis and stress-related effects are generally suspected as exacerbating symptoms of the peri-menopause transition, much more information is needed. Males also exhibit age-related reproductive decline albeit more gradual than in females.14 Moreover, there is evidence for benefits of dietary interventions including caloric restriction.8,15,16 A key element in the aging process is increasing disruption in biological rhythms; in the case of reproductive endocrine function there are altered circadian rhythms that occur even at the level of the pituitary gland.17 This breakdown in circadian rhythms also appears to be a fundamental aspect of the process of aging for physiological rhythms in general and is expressed in sleep-wake cycles and other behavioral responses.

Neuroendocrine systems and aging

Although declining ovarian reserve and the associated decrease in steroid production are critical triggers in reproductive aging, neural systems also show a concomitant deterioration in functional response. The gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) system is the primary hypothalamic regulator of reproduction. Despite extensive study to understand the role of the GnRH system in age-related reproductive failure, it has been difficult to discern clear changes in cellular morphology or integrity of the function response of neural systems that occur in correlation with diminished ovarian function and the peri-menopause transition.4 Recent data revealed altered functional responses of the GnRH system that contribute to fundamental biological changes that occur in the reproductive axis during aging.6–8 The difficulties in identifying and characterizing these age-related changes are captured eloquently in the manuscript by Gore and colleagues (see this volume). They also describe the background provided by studies that measured GnRH release using push-pull perfusion. These studies documented different patterns in aging female rats and rhesus macaques by characterizing the neural mechanisms that regulate GnRH release at the level of the median eminence. As pointed out by the authors, there are differences in age-related changes which likely reflect different phases in the aging process. These include the transitional phase that occurs during the loss of ovarian function and concomitant decline in ovarian steroids. This phase is followed by the next phase as ovarian steroid feedback to the hypothalamus diminishes; and neural systems attempt to compensate for the loss of estradiol by increasing amplitude and frequency of GnRH release. As Yin and Gore (see this volume) have observed, the glial cells that surround the GnRH axonal terminals have the capacity to modulate release of GnRH. The significance of an age-related change in the interaction of GnRH axonal terminals and the surrounding tanycytes in the median represent a fundamental piece of the puzzle in terms of the functional elements of hypothalamic systems as they become altered in aging female rats. Ultimately, these changing interactions and altered modulation of GnRH combine with changing signals from the ovarian steroids to produce an age-related functional response leading to eventual reproductive failure.

Parallel findings from comparative studies in the quail model

We have conducted studies on reproductive endocrine and behavioral aging in a short-lived avian model, the Japanese quail. Our initial studies revealed that the process of aging follows a chronological pattern similar to that observed in mammals. That is, male Japanese quail undergo a gradual loss in the frequency and intensity of sexual behavior.. The regulation and age-related decline mirror processes observed in mammals, especially those observed in primates that transition from regular cycles to irregular cycling and finally ovarian failure. As pointed out by Finch and Holmes (see this volume), the age-related loss of ovarian reserve parallels that observed in mammals. Similarly, there is a period of unopposed estrogen exposure during which ovulation does not reliably occur followed by collapse of ovarian function and reproductive failure.

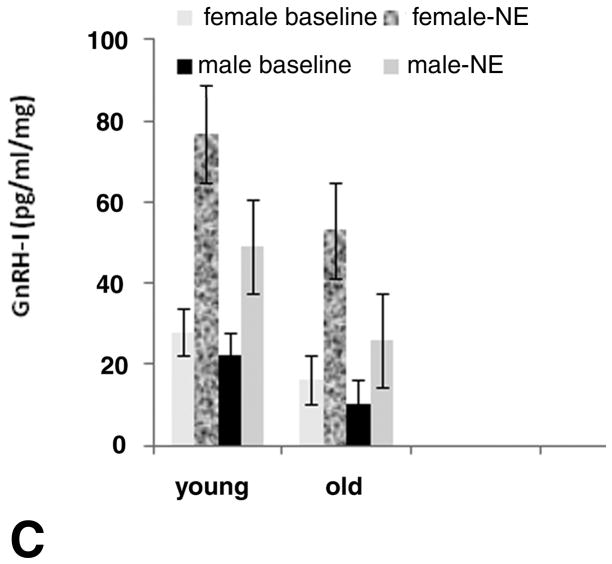

A number of molecular forms of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) have been identified in other species and classes of vertebrates. In quail, of the two forms of GnRH, GnRH-I is the reproductively active form secreted under the modulation of the neural system that regulates reproductive endocrine function. Neurons containing GnRH-I originate from the preoptic-septal region with release at the median eminence, similar to mammals.7 In addition to conserved anatomical location of the GnRH system, we have shown an age-related decrease in GnRH-I release in vitro from hypothalamic slices taken from young and from reproductively senescent male and female quail (Figure 2).18 As shown in Figure 2a and b, young females and males show strong response to norepinephrine (NE) release (denoted by the bars on the figures); whereas reproductively senescent females and males show reduced response to NE stimulation and a more erratic release response. When averaged over males and females, both baseline and NE induced GnRH-I release diminish with age (Figure 2c). These data show similar GnRH-I release patterns to those reported in reproductively senescent mammals, reinforcing the contention that many of the age-related changes are conserved across vertebrate classes.13–16

Figure 2.

In vitro release of gonadotropin releasing hormone-I (GnRH-I) from parasaggital slices of hypothalamus. Slices were taken from young reproductive and old senescent males and females. An age-related diminution in pulse height occurred in response to norepinephrine (NE) stimulation, which was administered as a single injection made at 3–4 time points (denoted by bars) in both females (A) and males (B). Both baseline and NE induced GnRH-I differed with aging in males and females as shown in the bar graph (based on references 18 and 20).

A remarkable attribute observed in some non-mammalian species is the plasticity of neural systems throughout the life cycle and the ability to regenerate select tissues.. The latter has been demonstrated in phylogenetically lower species such as lizards that regenerate appendages and of course invertebrates that can regenerate major portions of their bodies. The neural plasticity observed in a number of species has been of great interest, especially when comparing reproductive aging in short or long lived species. Although not entirely surprising, given extensive studies on birth of new cells in the central nervous system throughout life, neural plasticity enables the individual to continue to reproduce during aging. A specific example is the Japanese quail, which is a short lived bird that undergoes age-related reproductive decline. As noted earlier, in males, similar to mammals, plasma androgen levels decline gradually accompanied by loss of reproductive behavior, including courtship and mating behaviors. Albeit the loss of behavior is not directly correlated to declining circulating androgen levels in aging mammals or birds, testosterone replacement restores male sexual behavior and the associated neural systems that modulate these behaviors.14,18,19 Study of these resilient neural systems and the mechanisms by which they are restored in aging individuals will augment our understanding of age-related alterations leading to reproductive senescence.

Environmental factors: endocrine disruption and potential effects on aging

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) that have endocrine activity in wildlife, domestic species, and humans. Because we all carry a body burden of environmental chemicals and EDCs, it is important to determine the potential impact of lifelong exposure and discern differences in vulnerability to exposure. There is also an issue of variable sensitivity according to the phase of the life cycle. Although EDCs are generally not lethal at field relevant concentrations, it has become clear that there are both species differences in sensitivity to EDCs as well as individual differences in response to EDC exposure.20 The question of early exposure to EDCs and effects on later reproductive lifespan may be a critical aspect of aging processes, especially if exposure attenuates reproductive function prematurely. In addition, it is important to consider lifetime exposure leading to a body burden of resident EDCs, especially in lipids stored in fat cells or liver. In birds and other wildlife, EDCs may alter sexual differentiation and impair reproductive success in adults.20 This is shown schematically for a species of migratory bird in Figure 3, in which optimal conditions foster maximal breeding success and higher exposure is predicted to result in reduced reproductive success in breeding pairs and potentially fewer birds reproducing over their lifespan. There are also compelling data showing that EDCs can directly impact the GnRH system as well as reproductive behavior, including courtship, mating, and parental behavior.20–22 EDC effects are likely to impact the sexual differentiation of neuroendocrine systems that modulate reproductive behavior during embryonic and early post hatch development. It is important to note that this relative exposure to estradiol and androgen is permuted by additional steroid or EDCs that interact with endogenous systems during this critical organizational period. Rather, it is a precise balance in exposure to steroids that dictate the organizational processes, making the avian system vulnerable to added steroid-like effects from EDCs. It is also becoming increasingly clear that precocial birds are more vulnerable to these organizational effects of EDCs during embryonic development; whereas, altricial species may suffer less effect from embryonic EDC exposure but greater lifetime impacts from EDCs.20 Therefore, there is evidence for neural effects of EDCs in both mammals and birds, which are likely to impact reproductive function in adults.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram showing the potential effects of exposure to EDCs over the lifespan of short lived (SL) or over part of the lifespan for long lived (LL) birds. The schematic is hypothetical and is based on information about longevity data from birds and the impact of EDCs on birds, both in field observations and from laboratory studies. In birds, reproduction peaks quickly in short lived birds and declines quickly with the short lifespan. In these species, intermittent exposure to EDCs would be predicted to impair reproduction, which may impact short lived species more drastically than long lived birds depending on the timing of exposure during the life cycle. High exposure would be deleterious for both short and long lived birds resulting in reduced fitness and possibly shortened reproductive lifespan (based on references 20 and 21).

Conclusions

In summary, there is evidence for conserved mechanisms in the process of age-related reproductive decline. Ovarian follicular reserve declines across species resulting in decreasing steroid production. As ovarian function declines, there is a period of elevated estrogen levels unopposed by ovarian progesterone owing to intermittent ovulation. This is followed by loss of circulating estradiol with the collapse of ovarian function and associated impacts on cognitive function. Coincidently, the hypothalamic GnRH system shows functional alterations attributable in part to the glial cells that modulate GnRH release from the axonal terminals. Studies in comparative models of aging support the contention that many of these processes are common among vertebrate species. Finally, environmental factors including smoking, diet, and EDCs are likely to alter reproductive function and the timing of reproductive senescence in individuals.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was prepared as a contribution to the Workshop on Reproductive Aging sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and Georgetown University and hosted by the Center for Population and Health at Georgetown University. The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Patricia Goldman, who encouraged me to enter into the world of aging research and Dr. Caleb Finch, who enabled many to pursue studies in the comparative biology of aging. I thank many other wonderful collaborators, especially at the NIA and ONPRC, who continue to travel with me in studies on aging and whose work is also cited in this manuscript. Special thanks to Dr. Julie Wu, who persisted in understanding the endocrine changes in aging non-human primates and to Dr. Mary Zelinski, a premier researcher and wonderful collaborator for all the studies on aging in primates. Research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH; NIH #U01-AG21380-03 (MZ and MAO); USEPA STAR grant (MAO); and NIH #1 R21-AG031387 (MAO).

References

- 1.Klein NA, Houmard BS, Hansen KR, Woodruff TK, Sluss PM, Bremner WJ, Soules MR. Age-related analysis of inhibin A, inhibin B, and activin a relative to the intercycle monotropic follicle-stimulating hormone rise in normal ovulatory women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2977–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, te Velde ER, Fauser BC, Bancsi LF, de Jong FH, Themmen AP. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels: a novel measure of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(12):3065–71. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.12.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JM, Zelinski-Wooten M, Ingram DK, Ottinger MA. Ovarian aging and menopause: Current theories and models. Exper Biol Med. 2005;230:818–828. doi: 10.1177/153537020523001106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JM, Takahashi DL, Ingram DK, Mattison JA, Roth G, Ottinger MA, Zelinski MB. Ovarian reserve tests and their utility in predicting response to controlled ovarian stimulation in rhesus monkeys. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20823. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremellen KP, Kolo M, Gilmore A, Lekamge DN. Anti-mullerian hormone as a marker of ovarian reserve. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45(1):20–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Downs JL, Urbanski HF. Neuroendocrine changes in the aging reproductive axis of female rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Biol Reprod. 2006;75:539–546. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.051839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottinger MA, Mattison JA, Zelinski MB, Wu JM, Kohama S, Roth GS, Lane MA, Ingram DK. The rhesus macaque: A biomedical model for human health issues, aging, and cognition. In: Michael Conn P, editor. Handbook of Models for Human Aging. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 457–468. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth GS, Mattison JA, Ottinger MA, Chachich ME, Lane MA, Ingram DK. Rhesus monkeys: Relevance to human health interventions. Science. 2004;305:1423–1426. doi: 10.1126/science.1102541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wise PM, Dubal DB, Wilson ME, Rau SW, Bottner M, Rosewell KL. Estradiol is a protective factor in the adult and aging brain: understanding of mechanisms derived from in vivo and in vitro studies. Brain Res Reviews. 2001;37:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, Gass ML, Stefanick ML, Lane DS, Hays J, Johnson KC, Coker LH, Dailey M, Bowen D. WHIMS Investigators. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:2663–2672. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downs JL, Mattison JA, Ingram DK, Urbanski HF. Effect of age and caloric restriction on circadian adrenal steroid rhythms in rhesus macaques. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:14412–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McShane TM, Wise PM. Life-long moderate caloric restriction prolongs reproductive life span in rats without interrupting estrous cyclicity: effects on the gonadotropin-releasing hormone/luteinizing hormone axis. Biol Reprod. 1996;54:70–75. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod54.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ottinger MA, Mobarak M, Abdelnabi MA, Roth GS, Proudman JA, Ingram Effects of caloric restriction on reproductive and adrenal systems in Japanese quail: Are responses similar to mammals, particularly primates? Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:967–975. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ottinger MA. Male reproduction: Testosterone, gonadotropins, and aging. In: Mobbs CV, Hof PR, editors. Functional Endocrinology of Aging. Vol. 29. Karger Press; 1998. pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sitzmann BD, Urbanski HF, Ottinger MA. Aging in male primates: reproductive decline, effects of calorie restriction and future research potential. AGE. 2008;30:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sitzmann BD, Mattison JA, Ingram DK, Roth G, Ottinger MA, Urbanski HF. Impact of moderate calorie restriction on the reproductive neuroendocrine axis of male rhesus macaques. Open Longevity Science. 2009;3:38–47. doi: 10.2174/1876326X00903010038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sitzmann BD, Mattison JA, Ingram DK, Roth GS, Ottinger MA, Urbanski HF. Effect of moderate calorie restriction on pituitary gland gene expression in the male rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) Neurobiol Aging. 2009 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottinger MA. Neuroendocrine aging in birds: Comparing lifespan differences and conserved mechanisms. Special issue of Aging Research Reviews entitled: Genetics of Aging in Vertebrates. 2007;6(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ottinger MA, I, Nisbet CT, Finch CE. Aging and reproduction: Comparative endocrinology of the common tern and Japanese quail. Amer Zoologist. 1995;35:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottinger MA, Lavoie E, Dean K, Sitzmann B, Quinn MJ., Jr . Endocrine disruption and senescence: Consequences for reproductive endocrine and neuroendocrine systems, behavioral responses and immune function. In: Tilson H, Harry J, editors. Neurotoxicology. 3. Informa Healthcare; New York, NY: 2008. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gore AC. Neuroendocrine systems as targets for environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(2 suppl):e103–e108. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottinger MA, Lavoie ET, Thompson N, Bohannon M, Dean K, Quinn MJ., Jr Is the gonadotropin releasing hormone vulnerable to endocrine disruption in birds? Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;163:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]