Abstract

Objective:

Adding a craving criterion—presently in the International Classification of Diseases, 1 0th Revision, diagnosis of alcohol dependence—has been under consideration as one possible improvement to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), and was recently proposed for inclusion by the DSM Substance-Related Disorders Work Group in the Fifth Revision of diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders. To inform cross-cultural applicability of this modification, performance of a craving criterion was examined in emergency departments in four countries manifesting distinctly different culturally based drinking patterns (Mexico, Poland, Argentina, United States).

Method:

Exploratory factor analysis and item response theory were used to examine psychometric properties and individual item characteristics of the 11 DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria with and without craving for each country separately. Differential item functioning analysis was performed to examine differences in the difficulty of endorsement (severity) and discrimination of craving across countries.

Results:

Exploratory factor analysis found craving fit well within a one-dimensional solution, and factor loadings were high across all countries. Results from item-response theory analyses indicated that both discrimination and difficulty estimates for the craving item were located in the middle of the corresponding discrimination and difficulty ranges for the other 11 items for each country but did not substantially increase the efficiency (or information) of the overall diagnostic scheme. Across the four countries, no differential item functioning was found for difficulty, but significant differential item functioning was found for discrimination (similar to other DSM-IV criteria).

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that, although craving performed similarly across emergency departments in the four countries, it does not add much in identification of individuals with alcohol use disorders.

Work is currently under way by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) Substance-Related Disorders Work Group to inform the Fifth Revision (DSM-V) of the diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders, with a look to improving the validity and utility of diagnosis (Helzer et al., 2007; Saha et al., 2006). This work has entailed analysis that has examined the inclusion of alcohol dependence and abuse into a single diagnostic category with a quantity/frequency measure (5+ drinks on an occasion for men and 4+ for women at least weekly) to tap the lower end of the severity spectrum (Saha et al., 2007) as well as consideration of the inclusion/exclusion of specific criteria. Of particular interest in this regard is the potential for a closer alignment of the DSM diagnostic classification with that of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10; World Health Organization, 1993).

Although there is substantial overlap of DSM and ICD diagnostic schemes, which have generally shown good agreement, the ICD-10 criteria have been found to (a) cast a wider net than DSM criteria for identifying alcohol dependence in the general population but not necessarily in clinical populations (Rapaport et al., 1993; Rounsaville et al., 1993) and (b) have a slightly higher reliability (Hasin et al., 2006; Rounsaville, 2002). The primary difference between the two sets of diagnostic criteria is that the ICD contains a criterion on alcohol craving (a strong desire or sense of compulsion to take the substance), which may account, in part, for observed differences. Craving—a self-reported characteristic of a state that may promote and maintain substance dependence, serving as a cue immediately before self-administration—is particularly appealing to be considered in the formulation of DSM-V because of a possible neurological or genetic basis (Martin et al., 2006). Although human brain imaging studies have documented a biological cue-induced craving response among alcohol dependent individuals (Weiss, 2005) and craving has been used as an outcome measure in studies of alcohol treatment (O'Brien, 2005), its definition is somewhat controversial, it may be multidimensional in nature, and uncertainty remains as to whether it represents a physiological or a behavioral state (O'Brien et al., 1998).

Much of the work to date on reformulation of the DSM-V has focused on analysis of data from the U.S. general population, including analysis of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; Grant et al., 2004; Keyes et al., 2009; Saha et al., 2006, 2007) and the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES), both of which also measured craving (Keyes et al., in press). Analysis using item response theory (IRT) was conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties of DSM abuse and dependence criteria when the NLAES alcohol craving item, "In your entire life, did you ever want a drink so badly that you couldn't think of anything else?" (and, if yes, the respondent was asked if that had happened in the last 12 months), was introduced as a criterion. The craving item was found to demonstrate relatively high discrimination and produced a model that captured individuals on the more severe end of the alcohol use disorder spectrum. Although the addition of the item produced an overall better fitting IRT model than when this criterion was not included, the authors concluded that craving did not identify individuals who would not have already been identified based on DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria and, therefore, was redundant with existing criteria (Keyes et al., in press). Additionally, the DSM-V Work Group conducted analysis to examine craving on data from the high-risk family study of the Collaborative Studies on the Genetics of Alcoholism (Bucholz and Agrawal, 2009). As in the NLAES analysis, IRT results indicated good fit. Craving demonstrated good discrimination and appeared to be among the more severe items in the adult sample, and the authors concluded that craving appears to warrant serious consideration as an addition to the DSM-V. The DSM-V Work Group subsequently proposed craving as a candidate for inclusion in the revised DSM-V as stipulated in the provisional criteria recently made public (American Psychiatric Association, 2010).

Although this research, based on analyses in the general population, is important, two limitations exist, which suggests that additional research is required for adequately informing the formulation of DSM-V. First, these results need to be replicated using different data sets, especially those across various types of clinical practice in which patients under consultation tend to have more symptoms and more severe symptoms than general population samples. Second, it is not clear what the impact may be of altering diagnostic criteria of the DSM-V alcohol use disorder diagnostic scheme across countries and cultures.

Given these same concerns in adding a quantity/frequency criterion (which has a large variation in prevalence across cultures and which may not necessarily be in the same direction as variation in alcohol abuse and dependence) to the DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria as noted above, Borges and colleagues (Borges et al., 2010) replicated analysis based on the NESARC data (Saha et al., 2006) in emergency department populations in four countries manifesting distinctly different culturally based drinking styles: Mexico, Poland, Argentina, and the United States. Mexico typifies a fiesta-drinking style (infrequent but heavy drinking), Poland typifies much of the central and eastern European heavy drinking of spirits, and Argentina typifies the Mediterranean drinking style (highly integrated but low quantities of alcohol, primarily wine), whereas the drinking style in the U.S. sample (Santa Clara, CA) varies across the three main ethnic groups of Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics.

Findings based on these four emergency department samples were in concordance with general population findings of a unidimensional continuum of alcohol use disorders in each site; however, cross-country variation in the difficulty of endorsing the heavy drinking criterion of 5+ drinks weekly/monthly for males/females was evident, and cross-cultural variation in differential item functioning, although observed among several of the DSM-IV criteria, was largest for this heavy-drinking measure (Borges et al., 2010). Although any modifications to the existing DSM diagnostic criteria must undergo scrutiny to understand the consequences of proposed changes, these findings underscore the importance of sensitivity analyses across countries and cultures.

Although both behavioral (O'Brien et al., 1998) and pharmacological (O'Brien, 2005) underpinnings give support to the possible inclusion of craving as a criterion in the reformulation of DSM alcohol use disorders, and craving may underlie symptoms reflecting an individual's loss of control over drinking, such as unsuccessful efforts to cut down (O'Brien, 2005), a new criterion should be added only if it can be shown to improve diagnosis in terms of reliability/validity and/or case finding (Keyes et al., in press).

Building on this prior research in the general population for reformulation of DSM diagnostic criteria, performance of a craving criterion is examined in seven emergency-department sites in the four countries analyzed above, to inform the cross-cultural applicability of proposed modifications to the DSM diagnostic criteria and consequences in a cross-cultural context. Exploratory factor analysis and IRT were used to examine psychometric properties and individual item characteristics, in terms of difficulty and discrimination, of the 11 DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria with and without craving for each country separately. Differential item functioning analysis was also performed to examine differences in the difficulty of endorsement (severity) as well as discrimination of craving across countries.

Method

Samples and data sets

The sample consists of seven emergency department sites in four countries, compiled as part of the Emergency Room Collaborative Alcohol Analysis Project (ERCAAP; Cherpitel et al., 2003), and includes 5,195 emergency department patients from one site in Santa Clara, CA (1995-1996; n = 1,429); three sites in Pachuca, Mexico (1996-1997; n = 1,417); one site in Mar del Plata, Argentina (2001; n = 978); and one site each in Warsaw and Sosnowiec, Poland (2002-2003; n = 1,501). Data at each site were collected using a similar methodology and instrumentation (Cher-pitel, 1989) in which a probability sampling design was implemented so that each shift was equally represented for each day of the week during the period data were collected in each emergency department. Across all studies, samples of injured and noninjured patients 18 years of age and older were selected from emergency department admission forms, which included walk-in patients as well as those arriving by ambulance, and reflected consecutive arrival at the emergency department. Once selected for the study and as soon as possible after emergency department admission, patients were approached with an informed consent to participate. They then underwent breath alcohol analysis and were administered a questionnaire about 25 minutes in length by trained interviewers while they were in the waiting room or treatment area and/or following treatment. Patients who were too severely injured or ill to be interviewed in the emergency department and who were subsequently hospitalized were interviewed later after their condition had stabilized.

Measures

Diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence and abuse/harmful drinking were obtained from an adaptation of the Alcohol Section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Core (World Health Organization, 1990) for a diagnosis of both DSM-IV and ICD-10 alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse/harmful drinking for the past 12 months. The CIDI diagnostic interview was developed as a joint project by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration and has been tested in 19 countries. The alcohol section of the CIDI has been found to perform well, is easy to use, and is acceptable to subjects in almost all cultures (Wittchen et al., 1991). DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence included the following seven domains: tolerance, withdrawal, drinking more than intended, unsuccessful efforts to control, giving up pleasures or interests to drink, spending a great deal of time in drinking activities, and continued use despite physical or psychological problems, whereas alcohol abuse criteria included consequences related to role performance, hazardous use (injury), legal problems, and social problems. The ICD-10 alcohol dependence criteria included the same domains as DSM-IV with the addition of a craving criterion: "Feel such strong desire to drink that couldn't resist it or think of anything else" (also taken from the Alcohol Section of the CIDI core [World Health Organization, 1990]).

Data analysis

Only current drinkers who reported drinking during the last 12 months were included in the analysis of alcohol use disorder in the past 12 months. Exploratory factor analysis was performed to examine dimensionality of the 11 exist-ing DSM-IV alcohol use disorder criteria, with and without craving, across the four countries. Both one- and two-factor models were estimated using Mplus 5.1 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2008) (Table 3). Dimensionality was examined by factor loadings, eigenvalues, and two-factor model factor correlation after oblique rotation, and model fit was assessed using standard measures such as the comparative fit index, root mean squared error of approximation, and standardized root mean square residual.

Table 3.

Exploratory factor analyses of AUD by Emergency Room Collaborative Alcohol Analysis Project sites

| Base model (DSM-IV 11 criteria) |

Model with craving (DSM-IV 11 criteria + craving) |

|||||||

| Variable | One factor | Two factors | One factor | Two factors | ||||

| Santa Clara, CA, United States | ||||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 0.888 | 0.971 | −0.084 | 0.892 | 0.980 | −0.094 | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 0.911 | 0.911 | 0.005 | 0.912 | 0.912 | 0.004 | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 0.906 | 0.932 | −0.024 | 0.904 | 0.915 | −0.008 | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 0.953 | 0.942 | 0.016 | 0.951 | 0.916 | 0.042 | ||

| Time spent (D) | 0.967 | 0.942 | 0.032 | 0.970 | 0.957 | 0.018 | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 0.958 | 0.966 | −0.005 | 0.959 | 0.959 | 0.003 | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 0.890 | 0.634 | 0.286 | 0.890 | 0.638 | 0.282 | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 0.810 | 0.189 | 0.676 | 0.808 | 0.190 | 0.675 | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 0.795 | 0.589 | 0.231 | 0.800 | 0.622 | 0.200 | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 0.881 | −0.006 | 0.958 | 0.875 | −0.006 | 0.956 | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 0.885 | 0.216 | 0.730 | 0.881 | 0.198 | 0.748 | ||

| Craving | — | — | — | 0.938 | 0.982 | −0.046 | ||

| Factor correlation | — | 0.867 | — | 0.868 | ||||

| Eigenvalue | 8.955 | 9.473 | 9.821 | 10.356 | ||||

| CFI | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | ||||

| TLI | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.000 | ||||

| RMSEA | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.000 | ||||

| Pachuca, Mexico | ||||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 0.888 | 0.743 | 0.163 | 0.895 | 0.806 | 0.150 | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 0.788 | 0.850 | −0.049 | 0.785 | 0.808 | −0.028 | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 0.963 | 0.987 | −0.004 | 0.961 | 0.896 | 0.112 | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 0.790 | 0.023 | 0.797 | 0.788 | 0.796 | −0.002 | ||

| Time spent (D) | 0.924 | 0.562 | 0.387 | 0.920 | 0.824 | 0.162 | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 0.877 | 0.452 | 0.451 | 0.873 | 0.939 | −0.092 | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 0.873 | 0.833 | 0.056 | 0.872 | 0.930 | −0.079 | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 0.901 | 0.174 | 0.763 | 0.899 | 0.805 | 0.157 | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 0.726 | 0.386 | 0.3860 | 0.720 | 0.781 | −0.088 | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 0.796 | 0.002 | 0.820 | 0.851 | 0.002 | 1.270 | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 0.857 | −0.062 | 0.953 | 0.858 | 0.706 | 0.243 | ||

| Craving | — | — | — | 0.866 | 0.636 | 0.349 | ||

| Factor correlation | — | 0.892 | — | 0.546 | ||||

| Eigenvalue | 8.189 | 8.905 | 8.939 | 9.735 | ||||

| CFI | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | ||||

| TLI | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | ||||

| RMSEA | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.000 | ||||

| Base model (DSM-IV 11 criteria) |

Model with craving (DSM-IV 11 criteria) |

|||||||

| Variable | One factor | Two factors | One factor | Two factors | ||||

| Mar del Plata, Argentina | ||||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 0.808 | 0.809 | 0.009 | 0.803 | 0.804 | −0.027 | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 0.778 | 0.783 | 0.243 | 0.783 | 0.772 | 0.298 | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 0.879 | 0.872 | −0.169 | 0.888 | 0.892 | −0.156 | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 0.842 | 0.846 | 0.018 | 0.841 | 0.834 | 0.182 | ||

| Time spent (D) | 0.943 | 0.937 | −0.274 | 0.939 | 0.945 | −0.170 | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 0.978 | 0.975 | −0.060 | 0.981 | 0.981 | −0.004 | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 0.921 | 0.926 | 0.089 | 0.923 | 0.920 | 0.092 | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 0.821 | 0.815 | −0.180 | 0.817 | 0.826 | −0.256 | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 0.818 | 0.820 | 0.086 | 0.812 | 0.807 | 0.118 | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 0.931 | 0.931 | −0.035 | 0.926 | 0.930 | −0.110 | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 0.881 | 0.888 | 0.217 | 0.881 | 0.875 | 0.172 | ||

| Craving | — | — | — | 0.876 | 0.875 | 0.025 | ||

| Factor correlation | — | −0.006 | — | 0.032 | ||||

| Eigenvalue | 8.563 | 9.134 | 9.308 | 9.887 | ||||

| CFI | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.999 | ||||

| TLI | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.999 | ||||

| RMSEA | 0.021 | 0.011 | 0.020 | 0.016 | ||||

| Warsaw and Sosnowiec, Poland | ||||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 0.746 | 0.821 | −0.219 | 0.746 | 0.805 | −0.213 | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 0.824 | 0.840 | −0.026 | 0.823 | 0.839 | −0.040 | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 0.788 | 0.902 | −0.304 | 0.781 | 0.882 | −0.333 | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 0.847 | 0.850 | 0.010 | 0.842 | 0.848 | −0.002 | ||

| Time spent (D) | 0.913 | 0.917 | 0.017 | 0.927 | 0.929 | 0.024 | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 0.868 | 0.907 | −0.089 | 0.873 | 0.903 | −0.083 | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 0.830 | 0.790 | 0.133 | 0.831 | 0.802 | 0.126 | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 0.791 | 0.768 | 0.086 | 0.784 | 0.775 | 0.059 | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 0.755 | 0.763 | −0.003 | 0.752 | 0.763 | −0.019 | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 0.953 | 0.659 | 0.678 | 0.953 | 0.722 | 0.633 | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 0.944 | 0.816 | 0.286 | 0.944 | 0.840 | 0.278 | ||

| Craving | — | — | — | 0.851 | 0.815 | 0.142 | ||

| Factor correlation | — | 0.293 | — | 0.226 | ||||

| Eigenvalue | 7.910 | 8.632 | 8.631 | 9.369 | ||||

| CFI | 0.995 | 0.999 | 0.995 | 0.999 | ||||

| TLI | 0.993 | 0.998 | 0.994 | 0.998 | ||||

| RMSEA | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.030 | 0.017 | ||||

Notes: AUD = alcohol use disorder; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

When unidimensionality was confirmed, a two-parameter logistic IRT model was built that estimated the difficulty of endorsing a criterion at a given latent alcohol use disorder level (severity or difficulty) and the ability of a criterion to discriminate respondents from lower to high levels of the latent alcohol use disorder continuum (discrimination). The specific IRT model estimated here is a two-parameter model (Muthén et al., 1991), which places a probabilistic structure on the set of observed DSM items xj, namely P(xy = 1|s,aj,bj) = exp(aj (s − bj)) / (1 + exp(aj (s − bj)), where s is the latent severity variable and aj and bj are called, respectively, the discrimination and difficulty parameters for variable / The difficulty parameter generally corresponds to the rate of endorsement of the item, whereas the discrimination parameter indicates the degree to which variance in the item aligns with that of the underlying severity factor.

In Mplus, confirmatory factor analysis models were fitted and the model parameter estimates rescaled to IRT metric to derive the estimates of difficulty and discrimination. Also obtained from the logistic IRT model were the maximum likelihood estimates of variances of respondent's underlying alcohol use disorder continuum level, depending on the parameter estimates of the criteria in the IRT model. The reciprocal of the variance at a given alcohol use disorder continuum level is thus a measure of the information one has as to a respondent's unknown alcohol use disorder severity level. The aggregate information curve was generated to visually represent the total amount of information provided by all criteria. The two-parametric IRT model was fitted for the four countries separately.

Finally, differential item functioning (Saha et al., 2006) was performed to test whether, at a given level of latent alcohol use disorder continuum, the difficulty and discrimination vary significantly across the four countries. PARSCALE (du Toit, 2009) was used for its capability to evaluate differential item functioning on both difficulty and discrimination.

Results

Table 1 shows the past-12-month prevalence rates of DSM-IV alcohol use disorder and dependence with and without the addition of the craving criterion. Although the prevalence of current alcohol use disorders among drinkers varied greatly across countries, ranging from 31% in the United States to 14% in Poland, prevalence was minimally increased by the addition of a craving criterion, ranging from a 0.9% increase in the United States to no increase in Mexico. Similarly, little change was found in the prevalence of dependence, alone, when craving was added.

Table 1.

Comparison of past-12-month prevalence rates of DSM-IV AUD and dependence with craving added among current drinkers

| Variable | Santa Clara,CA, United States | Pachuca, Mexico | Mar del Plata, Argentina | Warsaw and Sosnowiec, Poland |

| DSM-IV AUD | ||||

| (≥1 of 4 abuse criteria or ≥3 of 7 dependence criteria) | 31.0% | 21.2% | 17.4% | 13.8% |

| AUD adding craving | ||||

| (≥1 of 4 abuse criteria or ≥3 of 8 dependence criteria) | 31.9% | 21.2% | 17.5% | 14.0% |

| DSM-IV dependence | ||||

| (≥3 of 7 dependence criteria) | 19.8% | 12.6% | 8.8% | 5.7% |

| Dependence adding craving | ||||

| (≥3 of 8 dependence criteria) | 20.8% | 13.0% | 9.2% | 6.5% |

Notes: DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; AUD = alcohol use disorder.

Table 2 shows the proportion of drinkers endorsing each of the 11 existing DSM-IV criteria, as well as craving, among those meeting criteria for alcohol use disorders. The prevalence of the craving criterion also varied greatly across countries, ranging from 44.2% in the United States to 22.5% in Poland, and was located in the middle of the corresponding prevalence range for the other 11 items for each country, similar to rates of tolerance.

Table 2.

Proportion of DSM-IV dependence (D) and abuse (A) criteria and craving among those reporting positive AUD in the past 12 months

| Variable | Santa Clara CA, United States | Pachuca, Mexico | Mar del Plata, Argentina | Warsaw and Sosnowiec, Poland |

| D1: Tolerance | 46.7% | 27.6% | 31.3% | 23.2% |

| D2: Withdrawal | 57.6% | 58.6% | 33.9% | 53.6% |

| D3: Larger/longer | 63.9% | 62.9% | 57.4% | 45.7% |

| D4: Quit/control | 51.7% | 41.4% | 35.7% | 21.2% |

| D5: Time spent | 52.2% | 39.7% | 53.0% | 20.5% |

| D6: Activities given up | 40.6% | 30.2% | 28.7% | 16.6% |

| D7: Physical/psychological problems | 64.0% | 48.3% | 54.8% | 47.0% |

| A1: Neglect roles | 51.5% | 74.1% | 53.0% | 50.3% |

| A2: Hazardous use | 35.9% | 22.4% | 43.5% | 35.1% |

| A3: Legal problems | 30.8% | 8.6% | 10.4% | 15.2% |

| A4: Social/interpersonal problems | 64.0% | 36.2% | 40.9% | 51.7% |

| Craving | 44.2% | 27.6% | 30.4% | 22.5% |

Note: AUD = alcohol use disorder.

Results from exploratory factor analysis are shown in Table 3. Across the four countries, both one-factor and two-factor models exhibited acceptable model fit (comparative fit index and Tucker-Lewis index > .95, root mean squared error of approximation < .05), with and without craving, although slightly better fit was seen for the two-factor model. For the United States, three abuse criteria were heavily loaded on the second factor in the two-factor model without craving and did not change when craving was added, with a high correlation between the two factors (r = .87). For Mexico, one dependence criterion and the same three abuse criteria were also heavily loaded on the second factor, without craving (r = .89 between the two factors), but with the addition of craving, only legal problems continued to load on the second factor. For both Argentina and Poland, a single factor was prominently observed, with and without the craving criterion. (However, legal problems was cross loaded between the first and second factor in Poland, regardless of craving.) For the four countries, with and without craving, the first eigenvalue was much larger than the second, which was never larger than one. Taken together these findings show that across the four countries, unidimensionality (with and without craving) is a reasonable assumption with one latent alcohol use disorder continuum.

Table 4 shows the discrimination and difficulty estimates from the two-parameter logistic IRT models as well as the model fit index for the four countries, with and without craving. Adding craving did not substantially change the parameter estimates of the 11 existing DSM-IV criteria. The difficulty estimates for the craving criterion were located in the middle of the corresponding difficulty ranges compared with the other 11 criteria for each country, and discrimination estimates also fell into the middle range. A formal differential item functioning test (not shown) across country showed no significant difference in difficulty for craving, χ2(3) = 2.2, in contrast to such criteria as withdrawal, χ2(3) = 29.5, quit/control, χ2(3) = 22.7, and neglect role, χ2(3) = 23.8. Although a significant cross-country difference in discrimination was observed for craving, χ2(3) = 30.7, similar differences were found for all but two of the 12 test criteria, with quit/control exhibiting the largest differential item functioning on discrimination, χ2(3) = 78.9.

Table 4.

Item response theory analyses of AUD by Emergency Room Collaborative Alcohol Analysis Project sites

| Variable | Base model (DSM-IV 11 criteria) | Model with craving (DSM-IV 11 criteria +craving) | ||||

| Discrimination Severity (SE) | Severity (SE) | Discrimination Severity (SE) | Severity (SE) | |||

| Santa Clara, CA, United States | ||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 1.97(0.2) | 1.10(0.07) | 2.00 (0.2) | 1.09(0.07) | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 2.15(0.2) | 0.86(0.06) | 2.17(0.2) | 0.86 (0.06) | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 2.19(0.3) | 0.73(0.06) | 2.18(0.3) | 0.73 (0.06) | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 2.99(0.4) | 1.00(0.06) | 2.96 (0.4) | 1.00(0.06) | ||

| Time spent (D) | 3.52 (0.5) | 0.98 (0.06) | 3.69 (0.6) | 0.97 (0.06) | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 3.03(0.5) | 1.19(0.07) | 3.08 (0.5) | 1.18(0.07) | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 1.89(0.2) | 0.80(0.06) | 1.93(0.2) | 0.79 (0.06) | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 1.38(0.1) | 1.24(0.09) | 1.37(0.1) | 1.24(0.09) | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 1.39(0.2) | 1.52(0.11) | 1.41 (0.2) | 1.51 (0.10) | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 1.79 (0.2) | 1.52 (0.09) | 1.75(0.2) | 1.53(0.09) | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 1.73 (0.2) | 0.98 (0.07) | 1.70(0.2) | 0.98 (0.07) | ||

| Craving | — | — | 2.62(0.3) | 1.10(0.07) | ||

| BIC | 5,602.446 | 5,933.384 | ||||

| Sample-size adjusted BIC | 5,532.578 | 5,857.165 | ||||

| AIC | 5,497.188 | 5,818.557 | ||||

| Pachuca, Mexico | ||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 2.32(0.4) | 1.69(0.11) | 2.43 (0.4) | 1.69(0.11) | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 1.38(0.2) | 1.14(0.10) | 1.36(0.2) | 1.15(0.10) | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 3.41(0.6) | 1.11(0.07) | 3.38 (0.6) | 1.11 (0.07) | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 1.33(0.2) | 1.44(0.12) | 1.34(0.2) | 1.44(0.11) | ||

| Time spent (D) | 2.88(0.5) | 1.46(0.09) | 2.75 (0.4) | 1.47(0.09) | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 2.14(0.4) | 1.67(0.11) | 2.08 (0.4) | 1.69(0.12) | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 1.88(0.3) | 1.30(0.09) | 1.85(0.3) | 1.30(0.09) | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 2.13(0.3) | 1.13(0.08) | 2.11(0.3) | 1.13(0.08) | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 1.23(0.2) | 2.18(0.23) | 1.21(0.2) | 2.20 (0.23) | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 1.76(0.4) | 2.39(0.25) | 1.95(0.5) | 2.32 (0.22) | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 1.91(0.3) | 1.62(0.11) | 1.94(0.3) | 1.62(0.11) | ||

| Craving | — | — | 1.91 (0.3) | 1.70(0.12) | ||

| BIC | 2,680.439 | 2,846.414 | ||||

| Sample-size adjusted BIC | 2,610.602 | 2,770.228 | ||||

| AIC | 2,585.741 | 2,743.107 | ||||

| Mar del Plata, Argentina | ||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 1.43(0.2) | 1.74(0.14) | 1.39(0.2) | 1.76(0.14) | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 1.26(0.2) | 1.72(0.14) | 1.29(0.2) | 1.71 (0.14) | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 1.99 (0.3) | 1.23 (0.09) | 2.06 (0.3) | 1.21 (0.08) | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 1.60(0.2) | 1.68(0.13) | 1.60(0.2) | 1.68(0.13) | ||

| Time spent (D) | 2.88(0.5) | 1.30(0.08) | 2.81 (0.5) | 1.30(0.08) | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 3.45(0.9) | 1.69(0.11) | 3.59 (0.9) | 1.68(0.10) | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 2.57 (0.4) | 1.25 (0.08) | 2.63 (0.4) | 1.25(0.08) | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 1.57 (0.2) | 1.58 (0.12) | 1.55(0.2) | 1.59(0.12) | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 1.49(0.2) | 1.74(0.14) | 1.45(0.2) | 1.76(0.14) | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 2.35 (0.7) | 2.32 (0.19) | 2.22 (0.6) | 2.35 (0.19) | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 1.87 (0.3) | 1.67 (0.12) | 1.86(0.3) | 1.67(0.12) | ||

| Craving | — | — | 1.84(0.3) | 1.73(0.13) | ||

| BIC | 2,907.884 | 3,097.797 | ||||

| Sample-size adjusted BIC | 2,838.033 | 3,021.596 | ||||

| AIC | 2,808.988 | 2,989.911 | ||||

| Warsaw and Sosnowiec, Poland | ||||||

| Tolerance (D) | 1.33(0.2) | 2.18(0.14) | 1.30(0.2) | 2.21 (0.15) | ||

| Withdrawal (D) | 1.58(0.2) | 1.44(0.08) | 1.58(0.2) | 1.44(0.08) | ||

| Larger/longer (D) | 1.28(0.1) | 1.61(0.10) | 1.26(0.1) | 1.62(0.10) | ||

| Quit/control (D) | 1.78(0.3) | 2.11(0.13) | 1.71(0.3) | 2.14(0.14) | ||

| Time spent (D) | 2.76(0.5) | 2.02(0.10) | 2.75 (0.5) | 2.03 (0.10) | ||

| Activities given up (D) | 2.13(0.3) | 2.21(0.12) | 2.07 (0.3) | 2.23 (0.13) | ||

| Physical/psychological problems (D) | 1.58(0.2) | 1.54(0.09) | 1.57(0.2) | 1.54(0.09) | ||

| Neglect roles (A) | 1.48(0.2) | 1.82(0.11) | 1.42(0.2) | 1.85(0.11) | ||

| Hazardous use (A) | 1.34(0.2) | 2.12(0.14) | 1.30(0.2) | 2.15(0.15) | ||

| Legal problems (A) | 2.38 (0.4) | 2.22 (0.13) | 2.33 (0.4) | 2.24(0.13) | ||

| Social/interpersonal problems (A) | 2.44(0.4) | 1.61(0.08) | 2.44 (0.4) | 1.61 (0.08) | ||

| Craving | — | — | 1.64(0.3) | 2.01 (0.13) | ||

| BIC | 4,054.591 | 4,327.394 | ||||

| Sample-size adjusted BIC | 3,984.713 | 4,251.164 | ||||

| AIC | 3,944.563 | 4,207.364 | ||||

Notes: AUD = alcohol use disorder; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; AIC = Akaike information criterion.

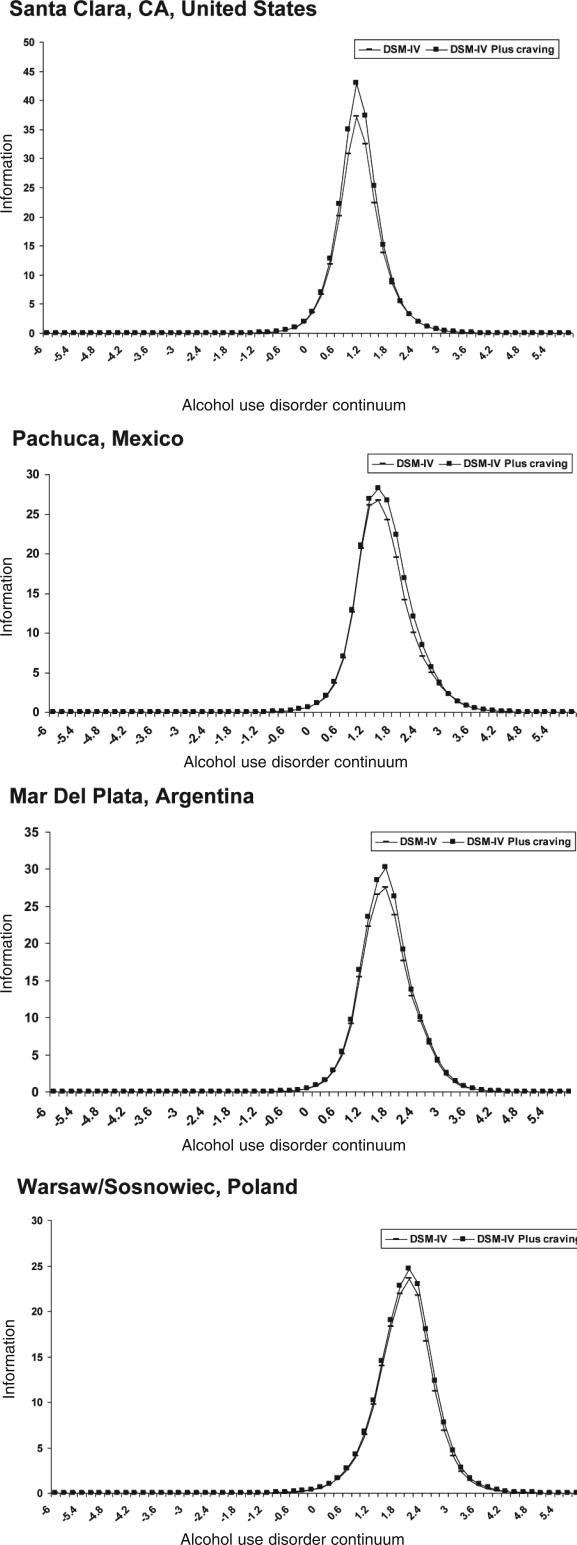

Figure 1 plots the aggregate information curve for each country for the 11 DSM-IV existing criteria and for the 12 criteria including craving. Although adding craving provides slightly more information, as reflected by a higher information curve peak, adding craving did not capture a substan-tially larger or different range of the underlying alcohol use disorder continuum.

Figure 1.

Aggregate information curves along latent alcohol use disorder continuum (x axis) for 11 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), existing criteria and 12 criteria with craving added Aggregate information curves along latent alcohol use disorder continuum (x axis) for 11 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), existing criteria and 12 criteria with craving added

Discussion

The prevalence of current alcohol use disorders among drinkers varied greatly across emergency department samples in these four countries, from 31% in the United States to 14% in Poland. However, prevalence was minimally increased by the addition of a craving criterion, ranging from a .9% increase in the United States to no increase in Mexico. Among those meeting criteria for alcohol use disorders, the prevalence of craving was located in the middle of the corresponding prevalence range for the other 11 items for each country, similar to rates of tolerance, and ranged from 44% in the United States to 23% in Poland.

Exploratory factor analysis found craving fit well within a one-dimensional solution, and factor loadings were high across all countries. Results from IRT analyses indicated that both the discrimination and the difficulty estimates for the craving criterion were located in the middle of the corresponding discrimination and difficulty ranges for the other 11 items for each country but did not substantially increase the efficiency (or information) of the overall diagnostic scheme. Across the four countries, no differential item functioning was found for difficulty, but significant differential item functioning was found for discrimination (similar to other DSM-IV criteria).

The operational definition of craving used in the ER-CAAP studies was similar—but not identical—to that used in NLAES ("In your entire life, did you ever want a drink so badly that you couldn't think of anything else?"), and similar findings here to those from NLAES (Keyes et al., in press) strengthen the generalizability of findings from the general population. Because of the rarity of endorsing craving (1.3%) in NLAES and the lack of additional cases identified, the authors suggest that a craving criterion is largely redundant in the context of the existing DSM-IV criteria and raises doubts about the utility of adding a craving criterion. Findings here support this conclusion, especially given that IRT analysis of the ERCAAP data did not find an increase in the total information provided when craving was added (as also found in the NLAES data). It should be noted that the craving criterion used in this study may represent a more severe form of craving (and in this regard may not encompass the broad range of craving), which may account for its relative lack of providing additional information. It is also important to note that this conclusion is based on the empirical findings reported here, and there may be other bases for considering the addition of a new criterion to an alcohol use disorder diagnosis. For example, a criterion that may be more fundamental to the neurophysiology of addiction (although this has been a subject of debate in relation to craving) and that may reflect pathophysiology, treatment, or outcomes could have added value in an alcohol use disorder diagnosis in relation to clinical decisions regarding treatment of dependence. Additionally, because craving is relatively rare among those not meeting existing criteria for alcohol dependence, if it is not included as a diagnostic criterion, it would be useful, clinically, to be described in the accompanying narrative for the disorder.

Prior research related to the current nosological classifications for alcohol dependence (Room et al., 1996; Üstün et al., 1997) has warned that not all criteria are similarly understood across different societies. Considerable crosscountry variation in these same samples was reported earlier in the difficulty of endorsing a heavy drinking criterion (5+ weekly/monthly for men/women) when added to DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorder (Borges et al., 2010), with similar variation also reported among several other DSM-IV criteria (but to a smaller extent than that exhibited by the heavy-drinking criterion). Although cultural factors may influence interpretation of or willingness to endorse specific dependence criteria (possibly reflected in the varying rates of prevalences of alcohol use disorder, regardless of craving, found here), variation in endorsement of the craving item across countries was not found in these clinical samples of emergency department patients (previously characterized as heavy chronic and acute drinkers; Cherpitel, 2007) from four countries demonstrating heterogeneous per capita consumption, drinking patterns, and drinking cultures. Homogeneity of results here within the cross-national nature of the samples widens the applicability of these findings.

Some limitations apply to this study. The present article was restricted to an examination of the performance and utility of adding a craving criterion to the existing DSM diagnostic classification scheme, with an eye to bringing it in closer alignment with that of the ICD. Within this context we have not examined other DSM alcohol use disorder criteria, and if scrutinized to this same level, it is possible that similar differences may be found.

Our aim was to determine cross-cultural differences in the performance of a craving criterion added to the proposed DSM-V alcohol use disorder nomenclature in a clinical sample of heavier drinkers; however, the four countries examined here, although exhibiting distinctly different drinking cultures and associated drinking patterns, are clearly not representative of all drinking cultures and certainly not all encompassing. Additionally, the emergency department samples analyzed here, although representative of patients treated in the particular emergency department facility, may be representative neither of other emergency department facilities in the region or country nor of their respective general population. It is also important to note that the type of emergency department and the system of emergency services delivery also varied across countries, which likely affected which individuals were available for inclusion in the sample in each of the countries. These differences across emergency departments and countries, coupled with possible variation in interpretation of items, may have resulted in some of the cross-cultural differences reported here—for example, the large variation in prevalence of alcohol use disorder found across the four country samples.

Nevertheless, findings here—based on epidemiological research in clinical populations where alcohol use disorders are likely more prevalent than in the general population as well as in countries with distinctly different drinking cultures and styles—inform the cross-cultural applicability of proposed modifications to the DSM diagnostic criteria in relation to adding a craving criterion. Taken together, these findings suggest that—although craving performed similarly across countries in the context of the analysis conducted here and does not appear to be a culturally sensitive criterion—craving does not increase the identification of individuals with alcohol use disorders and may not be a useful addition to proposed DSM-V alcohol use disorder nomenclature in this regard.

Footnotes

This research was supported by a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism supplement to grant 2 RO1 AA013750-04.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.) Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 development: Substance-related disorders. Arlington, VA: Author; 2010. Retrieved from http://wwwdsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/Substance-RelatedDisorders.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Cherpitel CJ, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Rubio-Stipec M. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption in a cross-national perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:240–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Agrawal A. Should craving be added as a criterion for alcohol use disorders in DSM-V? (abstract) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(Supplement):268A. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. A study of alcohol use and injuries among emergency room patients. In: Giesbrecht N, Gonzales R, Grant M, Öster-berg E, Room R, Rootman I, Towle L, editors. Drinking and casualties: Accidents, poisonings and violence in an international perspective. New York: Tavistock/Routledge; 1989. pp. 288–299. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. Alcohol and injuries: A review of international emergency room studies since 1995. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2007;26:201–214. doi: 10.1080/09595230601146686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Bond J, Ye Y, Borges G, Macdonald S, Giesbrecht NA. A cross-national meta-analysis of alcohol and injury: Data from the Emergency Room Collaborative Alcohol Analysis Project (ERCAAP) Addiction. 2003;98:1277–1286. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Toit M. SSI 2: Item response theory (IRT) from SSI. Lincoln-wood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International classification of diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl. 1):59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Bucholz KK, Gossop M. A dimensional option for the diagnosis of substance dependence in DSM-V. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16(Suppl. 1):S24–S33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Geier T, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Influence of a drinking quantity and frequency measure on the prevalence and demographic correlates of DSM-IV alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and the dimensionality of alcohol disorders. Psychological Medicine. in press doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Fillmore MT, Chung T, Easdon CM, Miczek KA. Multidisciplinary perspectives on impaired control over substance use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:265–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Kao C-F, Burstein L. Instructional sensitivity in mathematics achievement test items: Applications of a new IRT-based detection technique. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1991;28:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Mplus (Version 5.1.) Los Angeles, CA: Author; 1998-2008. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP. Anticraving medications for relapse prevention: A possible new class of psychoactive medications. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1423–1431. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: Can they explain compulsion? Journal ofPsychopharmacology. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport MH, Tipp JE, Schuckit MA. A comparison of ICD-10 and DSM-III-R criteria for substance abuse and dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1993;19:143–151. doi: 10.3109/00952999309002675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Janca A, Bennett LA, Schmidt L, Sartorius N. WHO cross-cultural applicability research on diagnosis and assessment of substance use disorders: An overview of methods and elected results. Addiction. 1996;91:199–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9121993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ. Experience with ICD-10/DSM-IV substance abuse disorders. Psychopathology. 2002;35:82–88. doi: 10.1159/000065124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Bryant K, Babor TF, Kranzler H, Kadden R. Cross system agreement for substance use disorders: DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and ICD-10. Addiction. 1993;88:337–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. The role of alcohol consumption in future classifications of alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün B, Compton W, Mager D, Babor T, Baiyewu O, Chatterji S, Sartorius N. WHO study on the reliability and validity of the alcohol and drug use disorder instruments: Overview of methods and results. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Current Opinion of Pharmacology. 2005;5:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U, Robins LN, Cottler L, Sartorius N. Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): Results of the multicentre WHO/ADAMHA field trials (wave I) British Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;151:645–653. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview: Authorized Core Version 1.0. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 1993. [Google Scholar]