Abstract

One of the most important physiological roles of brain astrocytes is the maintenance of extracellular K+ concentration by adjusting the K+ influx and K+ efflux. The inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1 has been identified as an important member of K+ channels and is highly concentrated in glial endfeet membranes. Aquaporin (AQP) 4 is another abundantly expressed molecule in astrocyte endfeet membranes. We examined the ultrastructural localization of Kir4.1, AQP4, α1-syntrophin, and β-spectrin molecules to understand the functional role(s) of Kir4.1 and AQP4. Immunogold electron microscopy of these molecules showed that the signals of these molecules were present along the plasma membranes of astrocyte endfeet. Double immunogold electron microscopy showed frequent co-localization in the combination of molecules of Kir4.1 and AQP4, Kir4.1 and α1-syntrophin, and AQP4 and α1-syntrophin, but not those of AQP4 and β-spectrin. Our results support biochemical evidence that both Kir4.1 and AQP4 are associated with α1-syntrophin by way of postsynaptic density-95, Drosophila disc large protein, and the Zona occludens protein I protein-interaction domain. Co-localization of AQP4 and Kir4.1 may indicate that water flux mediated by AQP4 is associated with K+ siphoning.

Keywords: astrocyte endfeet membranes, Kir4.1, aquaporin (AQP) 4, α1-syntrophin, localization

I. Introduction

The gliovascular complex comprises endothelial cells, subendothelial basal laminae, and astroglial cells. Highly polarized astroglial cells are characterized by the presence of perivascular membrane domains. The astroglial endfeet facing the basal lamina contain many molecules, such as water channel protein aquaporin (AQP) 4, dystrophin glycoprotein complex molecules, and the inwardly rectifying potassium channel protein Kir4.1.

The gating of Kir channel subunits plays an important role in polygenic central nervous diseases, such as white matter disease, epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease [15]. The expression of inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1 in perivascular astroglial endfeet has been described for murine brain [8, 12] and human brain samples [20, 23] and is called K+ siphoning [16], a function of potassium spatial buffering. The extracellular potassium rises by the action potential firing of neuronal cells which imparts astroglial cells with an elevated membrane permeability to potassium ion influx. This astroglial cell function mediated by potassium homeostasis is called potassium spatial buffering. The generation of osmotic gradients by K+ siphoning is thought be associated with the concomitant water flux that passes through AQP4 molecules. Kir4.1 is an important K+ channel member, is highly concentrated in glial endfeet membranes [9], and has an important role in spatial K+ buffering [10, 11]. Immunogold experiments using rat retina showed that the expression of Kir4.1 is closely associated with AQP4 in retinal Müller cell endfeet [13], implying that the water flux passing through AQP4 is associated with K+ siphoning [14, 17].

The aim of this study is to investigate the expression of AQP4, Kir4.1, α1-syntrophin, and β-spectrin at the gliovascular structures, and to examine ultrastructurally the spatial relationship of these membrane associated molecules at the astroglial endfeet membranes. In this study, we focused on observing astroglial endfeet membranes on the basal lamina side of brain capillaries. Our results using mouse cerebral samples confirmed the results of Nagelhus et al. [14] who used retinal Müller cells, and we further showed ultrastructural localization of α1-syntrophin, AQP4, and Kir4.1 in astroglial endfeet membranes by using immunogold electron microscopy.

II. Materials and Methods

Animal and tissue preparation

Normal mice (C57BL/10) were killed by cervical dislocation and their brains excised. The right half of the excised brain was fixed in neutral formalin for light microscopy immunohistochemistry, while the left half of the brain (cerebrum) was fixed for 24 hr in chilled 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for electron microscopy. As a rule, brain samples from three mice were embedded in paraffin for light microscopic immunohistochemistry of primary antibodies. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the ethics committee of Showa University (No. 30005).

Immunocytochemistry for light and electron microscopy

To examine by light microscopy whether the antibodies against Kir4.1, AQP4 and α1-syntrophin stain the brain capillary walls, the paraffin-embedded mouse brain cerebral samples were cut into thin (5 µm thick) slices with microtome, mounted on glass slides and deparaffinated. Deparaffinated cerebral slice samples were stained with primary antibodies using the immunoperoxidase method.

For immunogold electron microscopy, fixed cerebral samples from three mice for primary antibody or a combination of two primary antibodies experiments were frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and were cut into 5-µm thick slices using a cryostat. The thin sliced samples were collected in a vial and were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To eliminate nonspecific reactions, the sections were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in PBS containing 5% normal goat serum for single immunolabeling with antibody generated in rabbit or 5% normal donkey serum for that with antibody generated in sheep. For double immunolabeling experiments, sections were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in PBS containing 5% normal goat and donkey sera. For double immunolabeling experiments, we used two different polyclonal antibodies generated from the different animal species of rabbit and sheep. Table 1 lists the dilution titers of antibodies. For single immunolabeling, diluted primary rabbit or sheep antibody was applied to sections for 24 hr at 4°C, and 5 nm-gold labeled goat anti-rabbit or donkey anti-sheep secondary antibody was diluted 1:20 in PBS. For double immunolabeling, diluted primary rabbit and sheep antibodies were mixed and were applied together to the sections for 24 hr at 4°C. After thorough rinsing, 5 nm or 10 nm-gold labeled goat anti-rabbit (BB International, UK) and 10 nm or 5 nm-gold-labeled donkey anti-sheep (BB International, UK) secondary antibodies were diluted 1:20 in PBS. Appropriate combinations of the two diluted secondary antibodies of both sizes were prepared. The prepared secondary antibodies were applied either alone or together to the sections for 24 hr at 4°C, and were then washed three times in PBS. Control sections were incubated with the diluted sera of nonimmune rabbit or sheep, or both, instead of the respective primary antibodies.

Table 1.

Primary antibody

| Antigen | Antibody | Concentration of dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Kir 4.1 (Chemicon International Inc., USA) amino acid residues 356–375 of rat, mouse or human Kir4.1 (Accession P49655)-synthetic peptide | Rabbit polyclonal | 4 µg IgG/ml |

| Aquaporin 4 (AQP4) C-EKKGKDSSGEVLSSV (C-terminus) of the rat AQP4-synthetic peptide [7, 22] | Rabbit polyclonalSheep polyclonal | 5 µg IgG/ml5 µg IgG/ml |

| α1-Syntrophin amino acid residues 491–505 (C-terminus) of rabbit α1-syntrophin-synthetic peptide [21, 24] | Rabbit polyclonalSheep polyclonal | 5 µg IgG/ml5 µg IgG/ml |

| β-Spectrin (Transformation Research Inc., USA) extracted from human erythrocytes | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:100 |

To investigate the specificity of antibodies against AQP4 and α1-syntrophin, immunodepleted experiments with excess of the respective antigen as a negative control were done previously [21, 22] and the antibody specificity was verified. The antibody-labeled and control brain samples were additionally fixed in chilled 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 30 min, and were washed thoroughly. These samples were postfixed in chilled 2% OsO4 for 1 hr, were dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol and propylene oxide, and were embedded in Epon. For washing and embedding the samples, thin sliced samples were collected by centrifugation. The unstained ultrathin sections were observed using an electron microscope.

Evaluation methods of the spatial relationship between two different combined molecules among AQP4, Kir4.1, α1-syntrophin and β-spectrin

Electron micrographs of at least ten different sites of gliovascular structure were taken in each antibody combination of anti-AQP4 and Kir4.1, anti-Kir4.1 and α1-syntrophin, anti-AQP4 and α1-syntrophin, and anti-AQP4 and β-spectrin antibodies. As a rule, the original electron micrographs were taken at 40,000× and were printed at 160,000×. From these prints, the spatial relationship of gold particles of two different sizes were analyzed by using more than 100 gold particles in each antibody combination.

III. Results

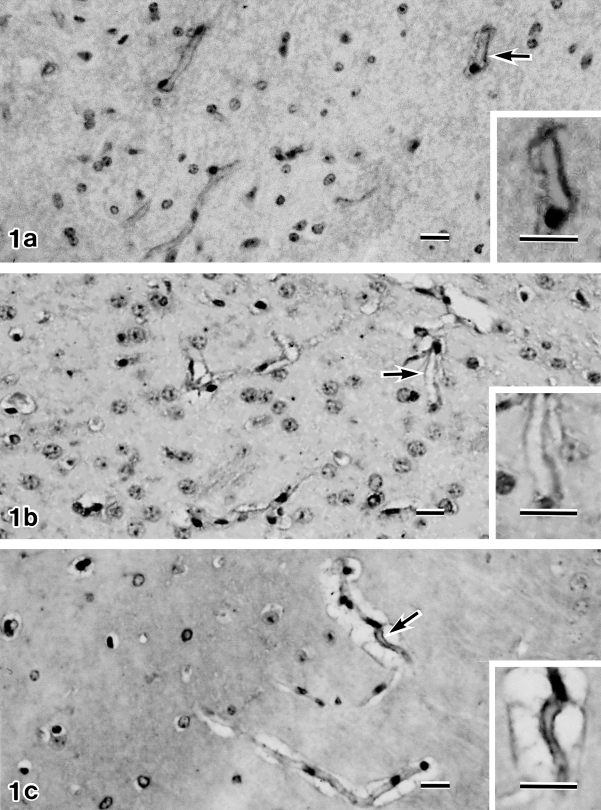

Immunohistochemical study of the capillaries of normal mouse brain showed that the immunoreactivities with antibodies against AQP4, Kir4.1, and α1-syntrophin localized in the capillary walls (Fig. 1a, b, c).

Fig. 1.

Light microscopy immunohistochemistry of normal mouse brain with antibodies against AQP4 (a), Kir4.1 (b) and α1-syntrophin (c). Brain sample immunostained with each antibody clearly shows capillary wall staining (arrow). Insets in lower right corner in a, b, c are higher magnification micrographs of the capillary indicated by arrow in a, b, c. Bars=25 µm (a, b, c), 25 µm (inset of a, b, c). a, b, c: 300×; inset of a, b, c: 600×.

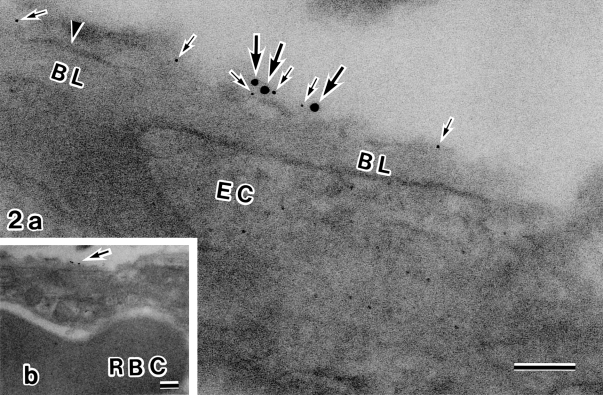

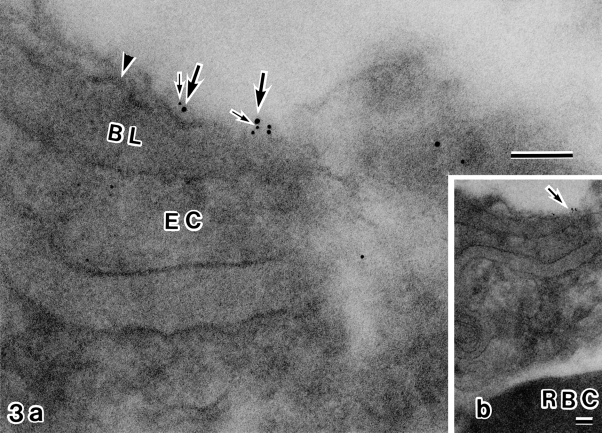

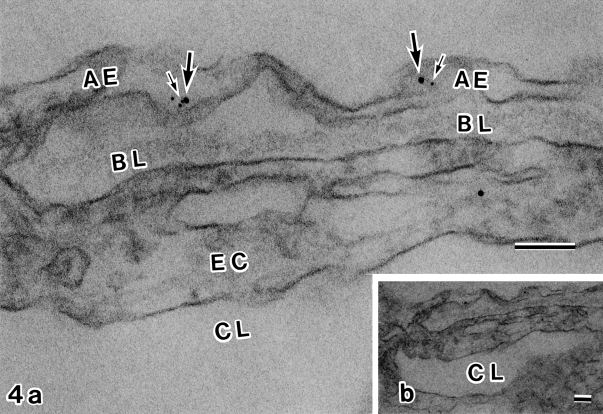

Single immunolabeling electron microscopy with antibodies against AQP4, Kir4.1, α1-syntrophin, and β-spectrin using mouse brain showed that gold particles were localized along the endfeet membranes of astroglial cells. Double immunogold labeling with antibody combinations against AQP4 and Kir4.1, Kir4.1 and α1-syntrophin and AQP4 and α1-syntrophin showed that 5 nm- and 10 nm-gold particles were closely associated frequently as doublets in the endfeet plasma membranes of astroglial cells (Figs. 2, 3, 4), but the association of 5 nm- and 10 nm-gold particles was less frequent for the antibody combination against AQP4 and β-spectrin. Immunoelectron microscopy of control brain samples showed no gold particles along the plasma membranes of astroglial endfeet. These electron microscopic findings were obtained in the astroglial endfeet membranes facing the capillary basal lamina, but not in those facing neuronal cells.

Fig. 2.

Double immunolabeling electron microscopy with antibodies against AQP4 (5 nm gold) and Kir4.1 (10 nm gold). A higher magnification view (a) of the area of (b) indicated by arrow. Part of the astroglial endfeet membrane (arrowhead) is seen on the opposite side of the capillary basal lamina (BL). Along the membrane are 5 nm (small arrows) and 10 nm (large arrows) gold signals which are closely associated. EC, endothelial cell; RBC, red blood cell. Bar=0.1 µm. a: 160,000×; b: 40,000×.

Fig. 3.

Double immunolabeling electron microscopy with antibodies against Kir4.1 (5 nm gold) and α1-syntrophin (10 nm gold). Higher power view (a) of the area of (b) indicated by arrow. Astroglial endfeet membrane (arrowhead) is seen on the opposite side of the capillary basal lamina (BL). Along this domain of astroglial membrane are 5 nm (small arrows) and 10 nm (large arrows) gold signals which are closely associated. EC, endothelial cell; RBC, red blood cell. Bar=0.1 µm. a: 160,000×; b: 40,000×.

Fig. 4.

Double immunolabeling electron microscopy with antibodies against AQP4 (5 nm gold) and α1-syntrophin (10 nm gold). (a) Higher power micrograph of the upper portion of (b). Astroglial endfeet (AE) are seen along the opposite side of capillary basal lamina (BL). Within the astroglial endfeet, 5 nm (small arrows) and 10 nm (large arrows) gold particles are closely associated. EC, endothelial cell; CL, capillary lumen. Bar=0.1 µm. a: 160,000×; b: 40,000×.

IV. Discussion

Light microscopy immunohistochemical studies have shown the expression of Kir4.1 in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes [18]. Later immunocytochemical studies reported that Kir4.1 channels are enriched during the process of astrocytes wrapping blood vessels in the brain and retinal tissues [8, 11]. The potassium channel Kir4.1 was shown to associate with α1-syntrophin in astroglial cells by using biochemical methods [3]. However, to the best of our knowledge we believe that the co-localization of Kir4.1 and α1-syntrophin in the plasma membranes of astroglial endfeet has not been shown before at the immunoelectron microscopic level, although the co-localization of these two proteins was shown at the light microscopic level [6]. So we investigated the ultrastructurally localization of AQP4, Kir4.1, and α1-syntrophin at the gliovascular interface around normal mouse brain capillaries. These molecules and β-spectrin were shown to be present in the plasma membranes of astroglial endfeet by single-immunolabeling. Double immunolabeling electron microscopy with antibody combinations Kir4.1 and α1-syntrophin, as well as AQP4 and α1-syntrophin, showed frequent co-localization of two molecular epitopes. However, double immunogold labeling study with antibodies against AQP4 and β-spectrin showed less frequent doublet formation at the same sites.

Glial cells, notably astrocytes, have an important role in maintaining homeostasis in the neuronal environment. Astroglial cells remove excess K+ around active neurons by several means, including spatial K+ buffering named K+ siphoning [16]. The generation of osmotic gradients by K+ siphoning is thought to be associated with the concomitant water flux, which has been confirmed experimentally [4, 19]. The water flux generated by the osmotic gradients due to K+ siphoning has to be mediated through AQP4, because K+ channels do not permit the movement of water to any great extent. Thus AQP4 and the relevant K+ channels, notably the inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1, are thought to cooperate to maintain environmental homeostasis around neuronal cells. Both AQP4 and Kir4.1 molecules interact with postsynaptic density-95, Drosophila disc large protein, and the Zona occludens protein I protein-interaction domain of α-syntrophin [1–3, 5]. Therefore, AQP4, Kir4.1 and α1-syntrophin are assumed to colocalize in astroglial membranes of the gliovascular interface. Colocalization of AQP4 and Kir4.1 has been described for rat retinal Müller cells [13].

In conclusion, this study confirmed the findings of Nagelhus et al. [14] for mouse brain astroglial endfeet membranes, and we further showed colocalization of Kir4.1 and α1-syntrophin, as well as AQP4 and α1-syntrophin, in the same membrane domains of astroglial cells.

V. Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by Intramural Research Grant (20B-13) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP. We wish to thank Professor Seiji Shioda, Department of Anatomy, Showa University School of Medicine for reviewing this paper and valuable suggestions, and Mrs. T. Nagami for her help in manuscript preparation.

VI. References

- 1.Adams M. E., Mueller H. A., Froehner S. C. In vivo requirement of the α-syntrophin PDZ domain for the sarcolemmal localization of nNOS and aquaporin-4. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:113–122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amiry-Moghaddam M., Otsuka T., Hurn P. D., Traystman R. J., Haug F. M., Froehner S. C., Adams M. E., Neely J. D., Agre P., Ottersen O. P., Bhardwaj A. An α-syntrophin-dependent pool of AQP4 in astroglial end-feet confers bidirectional water flow between blood and brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:2106–2111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437946100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connors N. C., Adams M. E., Froehner S. C., Kofuji P. The potassium channel Kir4.1 associates with the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex via α-syntrophin in glia. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:28387–28392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietzel I., Heinemann U., Hofmeier G., Lux H. D. Transient changes in the size of the extracellular space in the sensorimotor cortex of cats in relation to stimulus-induced changes in potassium concentration. Exp. Brain Res. 1980;40:432–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00236151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanning A. S., Anderson J. M. PDZ domains: fundamental building blocks in the organization of protein complexes at the plasma membrane. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:767–772. doi: 10.1172/JCI6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guadagno E., Moukhles H. Laminin-induced aggregation of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel, Kir4.1, and the water-permeable channel, AQP4, via a dystroglycan-containing complex in astrocytes. Glia. 2004;47:138–149. doi: 10.1002/glia.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa H., Ma T., Skach W., Matthay M. A., Verkman A. S. Molecular cloning of a mercurial-insensitive water channel expressed in selected water-transporting tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:5497–5500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higashi K., Fujita A., Inanobe A., Tanemoto M., Doi K., Kubo T., Kurachi Y. An inwardly rectifying K+ channel, Kir4.1, expressed in astrocytes surrounds synapses and blood vessels in brain. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C922–C931. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.3.C922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishii M., Horio Y., Tada Y., Hibino H., Inanobe A., Ito M., Yamada M., Gotow T., Uchiyama Y., Kurachi Y. Expression and clustered distribution of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel, KAB-2/Kir4.1, on mammalian retinal Müller cell membrane: their regulation by insulin and laminin signals. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:7725–7735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07725.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kofuji P., Ceelen P., Zahs K. R., Surbeck L. W., Lester H. A., Newman E. A. Genetic inactivation of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir4.1 subunit) in mice: phenotypic impact in retina. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:5733–5740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05733.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kofuji P., Biedermann B., Siddharthan V., Raap M., Iandiev I., Milenkovic I., Thomzig A., Veh R. W., Bringmann A., Reichenbach A. Kir potassium channel subunit expression in retinal glial cells: implications for spatial potassium buffering. Glia. 2002;39:292–303. doi: 10.1002/glia.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L., Head V., Timpe L. C. Identification of an inward rectifier potassium channel gene expressed in mouse cortical astrocytes. Glia. 2001;33:57–71. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(20010101)33:1<57::aid-glia1006>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagelhus E. A., Horio Y., Inanobe A., Fujita A., Haug F. M., Nielsen S., Kurachi Y., Ottersen O. P. Immunogold evidence suggests that coupling of K+ siphoning and water transport in rat retinal Müller cells is mediated by a coenrichment of Kir4.1 and AQP4 in specific membrane domains. Glia. 1999;26:47–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199903)26:1<47::aid-glia5>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagelhus E. A., Mathiisen T. M., Ottersen O. P. Aquapoprin-4 in the central nervous system: cellular and subcellular distribution and coexpression with Kir4.1. Neuroscience. 2004;129:905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neusch C., Weishaupt J. H., Bähr M. Kir channels in the CNS: emerging new roles and implications for neurological diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman E. A., Frambach D. A., Odette L. L. Control of extracellular potassium levels by retinal glial cell K+ siphoning. Science. 1984;225:1174–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.6474173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen S., Nagelhus E. A., Amiry-Moghaddam M., Bourque C., Agre P., Ottersen O. P. Specialized membrane domains for water transport in glial cells: high-resolution immunogold cytochemistry of aquaporin-4 in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:171–180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poopalasundaram S., Knott C., Shamotienko O. G., Foran P. G., Dolly J. O., Ghiani C. A., Gallo V., Wilkin G. P. Glial heterogeneity in expression of the inwardly rectifying K(+) channel, Kir4.1, in adult rat CNS. Glia. 2000;30:362–372. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(200006)30:4<362::aid-glia50>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ransom B. R., Yamate C. L., Connors B. W. Activity-dependent shrinkage of extracellular space in rat optic nerve: a developmental study. J. Neurosci. 1985;5:532–535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-02-00532.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saadoun S., Papadopoulos M. C., Davies D. C., Krishna S., Bell B. A. Aquaporin-4 expression is increased in oedematous human brain tumours. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2002;72:262–265. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakayama Y., Inoue M., Murahashi M., Shibuya S., Jimi T., Kojima H., Oniki H. Ultrastructural localization of α1-syntrophin and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in normal skeletal myofiber, and their relation to each other and to dystrophin. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:455–464. doi: 10.1007/s004010050733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakayama Y., Jimi T., Inoue M., Kojima H., Murahashi M., Kumagai T., Yamashita S., Hara H., Shibuya S. Reduced aquaporin 4 expression in the muscle plasma membrane of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch. Neurol. 2002;59:431–437. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warth A., Mittelbronn M., Wolburg H. Redistribution of the water channel protein aquaporin-4 and the K+ channel protein Kir4.1 differs in low- and high-grade human brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109:418–426. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0984-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang B., Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O., Moomaw C. R., Slaughter C. A., Campbell K. P. Heterogeneity of the 59-kDa dystrophin-associated protein revealed by cDNA cloning and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6040–6044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]