Abstract

Single molecule force spectroscopy is a powerful method that uses the mechanical properties of DNA to explore DNA interactions. Here we describe how DNA stretching experiments quantitatively characterize the DNA binding of small molecules and proteins. Small molecules exhibit diverse DNA binding modes, including binding into the major and minor grooves and intercalation between base pairs of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). Histones bind and package dsDNA, while other nuclear proteins such as high mobility group proteins bind to the backbone and bend dsDNA. Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding proteins slide along dsDNA to locate and stabilize ssDNA during replication. Other proteins exhibit binding to both dsDNA and ssDNA. Nucleic acid chaperone proteins can switch rapidly between dsDNA and ssDNA binding modes, while DNA polymerases bind both forms of DNA with high affinity at distinct binding sites at the replication fork. Single molecule force measurements quantitatively characterize these DNA binding mechanisms, elucidating small molecule interactions and protein function.

Keywords: force spectroscopy, DNA binding, DNA melting, DNA replication, nucleic acid chaperones

1 INTRODUCTION

Single molecule methods have provided a clearer understanding of a wide range of fundamental biological processes, including DNA replication, transcription, and repair. Single molecule force spectroscopy began with the capture and manipulation of single DNA molecules. Techniques such as optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers, and atomic force microscopy (AFM) apply forces to single molecules, probing conformational changes and structural dynamics in a variety of conditions. Such measurements explore the interactions of DNA with molecules ranging from small ligands to complex proteins. Quantifying the thermodynamics and kinetics of these interactions leads to substantial insights into DNA binding mechanisms in important biological systems.

1.1 Single molecule force spectroscopy techniques

Optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers, and AFM are the predominant force spectroscopy techniques used to trap and manipulate single DNA molecules. Single-beam optical tweezers instruments focus a high power laser through a high numerical aperture microscope objective to form an optical trap. Dual-beam optical tweezers instruments use microscope objectives to bring two counter-propagating laser beams to an overlapping focus to form an optical trap. The trap captures one typically streptavidin-coated polystyrene bead, while a second bead is attached to a micropipette tip fixed to a flow cell or is held in another optical trap. A single biotin-labeled DNA molecule is tethered to the beads through a biotin-streptavidin linkage or some other attachment method that can withstand the forces to be applied. Translation of the flow cell or optical trap pulls the bead affixed to the pipette tip or held in the trap, resulting in extension of the captured DNA molecule. This displaces the bead in the optical trap, which provides a measurement of the force on the DNA molecule with piconewton (pN) accuracy [1].

Magnetic tweezers use a glass slide and magnetic bead, both coated with streptavidin or another attachment ligand, in order to capture a biotin-labeled DNA molecule. Translation of the glass slide through a magnetic field gradient results in a force on the DNA molecule, measured as three-dimensional motion of the magnetic bead in video acquisition. Advantages of this technique include single molecule manipulation in three dimensions and detection of forces as low as 0.05 pN [2].

Although AFM is predominantly used in imaging applications, the technique may be used for single molecule force spectroscopy. A single DNA molecule is immobilized between the surface and the AFM tip, and force is measured as a function of extension and relaxation. A typical DNA attachment technique functionalizes opposite ends of the molecule with thiol and biotin. The thiolated end binds covalently to a gold surface, while the streptavidin-coated AFM tip captures the biotin-labeled end of a single DNA molecule [3]. Resolution of the DNA stretching curves is on the order of 5-10 pN [4-5].

1.2 Stretching single DNA molecules

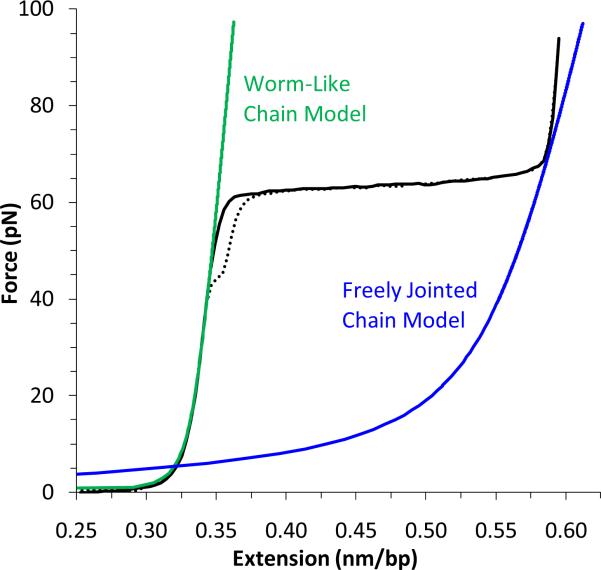

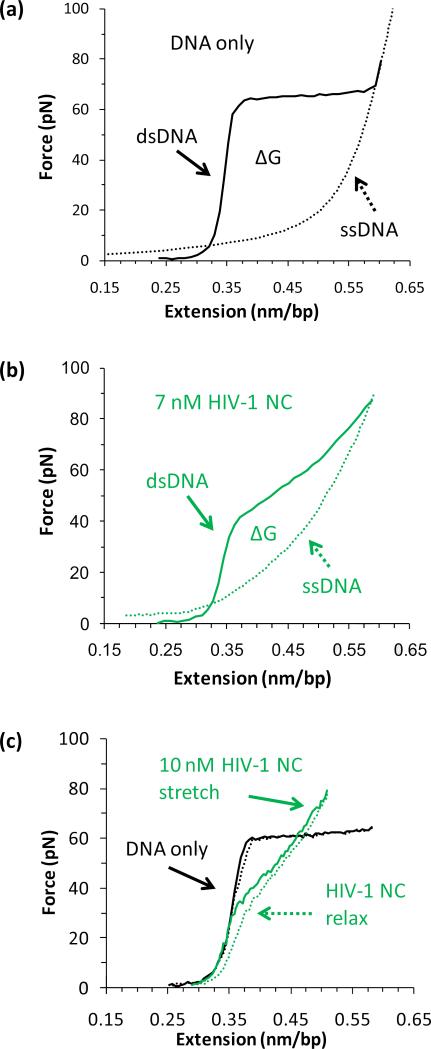

Single molecule DNA stretching experiments determine force as a function of extension (Figure 1). At low extensions, the measured tension increases gradually as the duplex uncoils in what is known as the entropic regime. As extension approaches the dsDNA contour length, the backbone resists further extension and the force increases dramatically in an elastic response. At ~65 pN, dsDNA undergoes an overstretching transition, increasing to ~1.7 times its contour length at nearly constant force. There is a second transition at the end of this overstretching plateau, near the contour length of ssDNA. If the extension is reduced at this point, the relaxation curve will match the stretching curve. Some hysteresis, where the relaxation curve does not match the stretching curve may occur, depending upon solution conditions. DNA stretching and relaxation cycles exhibit similar force-extension curves on the timescale of the experiment in typical solution conditions, indicating that the process is reversible.

Figure 1.

DNA stretching experiments measure the force on a dsDNA molecule as a function of extension. The extension data for a typical λ-DNA molecule is shown as a solid black line, and a dotted line represents the relaxation data. The Worm-Like Chain (WLC) model (green line) describes dsDNA. Near the dsDNA contour length, the molecule undergoes a force-induced melting transition, from dsDNA to ssDNA. The Freely-Jointed Chain (FJC) model describes ssDNA (blue line). Minimal hysteresis is evident in these solution conditions (100 mM Na+, 10 mM Hepes, pH = 7.5, T = 20 °C).

1.2.1 Models of polymer elasticity

Polymer models of dsDNA and ssDNA effectively characterize DNA force-extension curves. The Worm-Like Chain (WLC) model assumes a smooth distribution of bending angles, and describes dsDNA in terms of observed length bds of an elastic polymer under the influence of tension F [6-10]. Though no exact solutions to this model are known, an approximate solution is appropriate for high forces:

| (1) |

where Pds is the persistence length, Bds is the end-to-end or contour length, and a stretch modulus Sds is added to account for backbone extensibility. Here kB is Boltzmann's constant and T is temperature. The Freely Jointed Chain (FJC) model describes the polymer elasticity of ssDNA as a collection of independent monomers with varying bond angles [11]:

| (2) |

Figure 1 shows the WLC (green) and FJC (blue) polymer models with typical values for the parameters B, P, and S [1, 12].

1.3 Force-induced structural transitions

A thermodynamic model quantitatively describes the overstretching transition at 65 pN in terms of force-induced melting. The force exerted on the dsDNA molecule does work to increase the length of the DNA, converting dsDNA to ssDNA and disrupting both base pairing and base stacking interactions. In this model, the second transition at the end of the melting plateau is a non-equilibrium process involving the remaining base pairs of dsDNA which must break for strand separation. Force-induced melting is analogous to thermal melting, and the model predicts that solution conditions which influence thermal melting, such as salt, pH, and temperature, also affect the force-induced melting transition. DNA stretching experiments quantitatively confirmed these predictions [10, 13-14], and recent modeling studies also support a force-induced melting model [15-17]. Furthermore, experiments demonstrated that solution conditions [18] and DNA binding ligands [19-26] known to inhibit DNA reannealing induce strong hysteresis in the force-extension curves, providing additional evidence for melting of the DNA strands.

In an alternate model of the overstretching plateau, B-form duplex DNA lengthens in response to the applied force, undergoing a structural transition to a new form of DNA referred to as “S-DNA” [4, 27-29]. This form of DNA is predicted to preserve base pairing but not base stacking, a distinction based upon the observation that strand separation occurs at high forces [30-32]. An early modeling study predicted a transition to this form of DNA at a significantly larger force than experiments observed. Recent studies use the proposed existence of S-DNA as a means to generate new parameters to fit stretching curves and other experimental results. However, it is not clear that additional fitting parameters are needed to explain DNA stretching experiments. In addition, these models do not make predictions that can be tested with other experiments, making it difficult to test proposed S-DNA models [33-35]. Magnetic tweezers experiments with both strands of a dsDNA molecule tethered to beads did not observe the transition at 65 pN, but instead measured a transition at 110 pN over a similar extension attributed to a combination of S-DNA and P-DNA, a form of melted DNA which is overwound [36]. Although this particular transition of torsionally constrained DNA is consistent with force-induced melting, it was suggested that some features of DNA stretching curves were incompatible with force-induced melting [37-38] and that the structure of DNA in the overstretching transition remains unclear [39-40]. It is essential to establish the nature of the overstretching transition in order to use single molecule force spectroscopy techniques to characterize DNA binding. Recent experiments use glyoxal, intercalating dyes, and single-stranded binding proteins (SSBs) to establish that this conformational transition involves base pair disruption, and therefore DNA overstretching is force-induced melting of dsDNA into ssDNA.

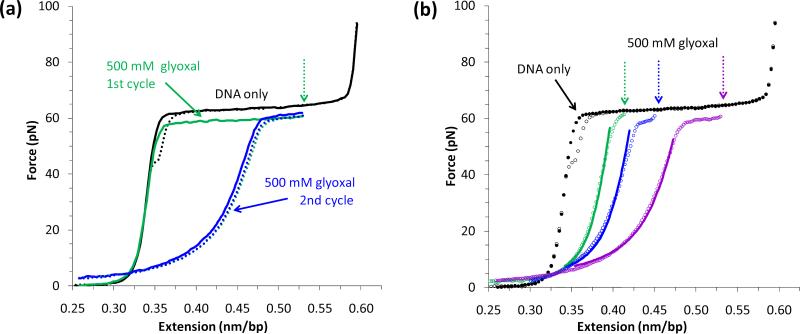

1.3.1 Glyoxal binds ssDNA bases exposed in the force-induced melting transition

Glyoxal (C2H2O2) is a small molecule which binds irreversibly to exposed guanine bases of DNA with slow kinetics [41]. The modified guanine bases have three rings instead of two, introducing steric constraints that hinder base pair reannealing [42]. λ-DNA molecules were held at fixed extensions for ~30 min in the presence of glyoxal, which is the timescale required for DNA binding [41]. The DNA stretching curve exhibits a decrease in melting force and strong hysteresis (Figure 2a), indicating that guanine bases exposed to solution are subject to glyoxal modification and subsequently prevent DNA reannealing [41]. Therefore extension into the overstretching plateau exposes ssDNA bases to solution, reflecting force-induced melting of the dsDNA molecule.

Figure 2.

Glyoxal binds ssDNA bases exposed in the force-induced melting transition. (a) Extension (solid line) and relaxation (dotted line) data of a λ-DNA molecule alone is shown in black. After the addition of 500 mM glyoxal, the molecule is extended (solid green line) and held fixed (green dotted arrow) for ~30 min. The significant hysteresis upon relaxation (dotted green line) reflects that the two DNA strands do not reanneal, indicating glyoxal binding to exposed nucleotides. The second stretch (solid blue line) follows the previous relaxation curve, which suggests that modification is permanent. (b) Relaxation data (open circles) for a series of fixed extensions (dotted arrows), in which the DNA molecule is stretched in the presence of 500 nM glyoxal. Fits to a linear combination of the WLC and FJC models (Equation (3)) are shown as solid lines. Figures reproduced with permission from [1].

As the DNA molecule is held at larger fixed extensions, the corresponding relaxation curves exhibit additional hysteresis (Figure 2b). These results demonstrate that glyoxal binding increases as the DNA molecules are held further into the overstretching plateau, despite constant solution conditions. This indicates that greater extensions into the stretching transition result in exposure of additional bases, and the relaxation curves in the presence of glyoxal are a combination of dsDNA and ssDNA. The experimental data fits well to a linear combination of the FJC and WLC polymer models (fits shown in Figure 2b), where the measured contour length b is a function of the ssDNA fraction γss [41]:

| (3) |

and bds and bss are force-dependent DNA extensions from the WLC (Equation (1)) and the FJC model (Equation (2)), respectively. The fractional extension along the transition plateau agrees well with the fraction of glyoxal-stabilized ssDNA obtained from fits to Equation (3), which provides structural evidence that DNA overstretching is indeed the force-induced melting of dsDNA into ssDNA.

1.3.2 Visualizing force-induced melting with intercalators and SSBs

The significant presence of ssDNA exposed to glyoxal modification in the overstretching transition is unlikely to arise from nicks in the DNA backbone [43], and further experiments with small molecules and SSBs confirm the force-induced melting model. Recent single-molecule studies have directly visualized the nature of the structural transition in a combination of optical tweezers and fluorescence imaging techniques [44]. A DNA molecule stretched to a fixed extension in the absence of ligand is briefly transferred into the presence of YOYO, a fluorescent dye which intercalates into the paired bases of dsDNA [45]. Subsequent imaging reveals only regions of dsDNA, to which the intercalator can bind [44]. The fraction of dsDNA present at each fixed extension corresponds directly to fractional extension along transition plateau, illustrating a structural conversion from dsDNA into a form of DNA to which YOYO is unable to bind [44].

Experiments with fluorescent dye-labeled SSBs demonstrate that the form to which dsDNA is converted upon overstretching is ssDNA. Human mitochondrial SSB (mtSSB) binds and wraps relaxed ssDNA [46], but does not affect the overstretching transition or bind ssDNA which is under tension greater than ~40 pN. When DNA is extended into the stretching transition and briefly placed in the presence of mtSSB, the images show fluorescent spots at both ends of the DNA molecule, indicating the presence of protein-wrapped ssDNA [44]. These spots increase in brightness and move toward the center of the molecule as a function of extension, illustrating the relative increase of ssDNA with progressive movement into the stretching transition. This method also visualizes nicks in the DNA backbone, since the mtSSB wraps the relaxed ssDNA in the middle of the molecule. Molecules without nicks do not exhibit these binding events, and mtSSB fluorescence is confined to the ends of the DNA. Two-color fluorescent measurements with both YOYO and mtSSB confirm that mtSSB-wrapped ssDNA forms at an interface with YOYO-labeled dsDNA [44].

In contrast with mtSSB, the SSB Replication Protein A (RPA) binds ssDNA under tension of at least 70 pN. RPA is able to bind both ssDNA under tension and relaxed ssDNA without wrapping it [47]. Two-color fluorescence measurements with eGFP-labeled RPA and bis-intercalator POPO-3 show three fluorescent regions [44]. The dsDNA segment has two bright spots of relaxed ssDNA on either side, followed by two ssDNA strands extending out to their respective attachment sites on each bead. Application of flow perpendicular to the axis of the molecule stretches out the relaxed ssDNA, clearly illustrating both strands of ssDNA created upon dsDNA overstretching [44].

Similar experiments with a DNA molecule attached to beads on both strands reveal the torsionally-constrained transition at 110 pN, with sites of POPO-3-labeled dsDNA and RPA-labeled ssDNA throughout the molecule [44]. The negative correlation of dsDNA and ssDNA areas on the same DNA molecule implies spatial separation of melted regions, with no evidence to support an interpretation of separate S-DNA and P-DNA phases [48]. The data also indicate that short regions of dsDNA remain when DNA is stretched to forces beyond the overstretching transition (in the second transition at the end of the overstretching plateau, near contour length of ssDNA). Thus, complete separation of the strands require application of unexpectedly high forces, but most of the DNA has been melted by force during overstretching [44]. Although this pulling-rate dependent transition [4, 49] is not well-described, it exists even in the presence of ssDNA binding ligands, which is unexpected in the S-DNA model [48].

The results of these single-molecule fluorescence imaging experiments are consistent with formation of ssDNA during both structural transitions, an observation which is incompatible with the prediction of unexposed individual bases of the S-DNA model. Thus the overstretching transition is a force-induced melting transition, in which the applied force does work to melt dsDNA into ssDNA. Therefore DNA stretching experiments involve melting of the two strands. This result can be used as a basis for investigation of the biophysical mechanisms of DNA-ligand interactions with single molecule force spectroscopy techniques.

2 DNA BINDING LIGANDS: SMALL MOLECULES

DNA-ligand interactions are relevant to fundamental intracellular processes such as DNA replication, transcription, and the regulation of gene expression. Small molecules that bind DNA can interfere with these processes, and thus play a key role in rational drug design for complex diseases such as cancer and AIDS. Furthermore, a detailed understanding small molecule binding to DNA may provide insight into the DNA binding properties of larger, more complex molecules such as proteins. Small molecules may bind DNA covalently, which is an essentially irreversible interaction, or non-covalently in a reversible process. Although covalent DNA binding has been examined with single molecule force spectroscopy, the focus has been on reversible binding of small molecules. Intercalation and groove binding are reversible binding modes which may be distinguished with optical tweezers experiments. When DNA is stretched in the presence of small ligands, their influence on the mechanical properties of the DNA molecule may be measured in order to determine their binding mechanisms. Single molecule stretching methods may also resolve multiple binding modes such as bis-intercalation and threading intercalation.

2.1 Cross-linkers

Force spectroscopy studies of irreversible DNA binding has been limited to cross-linkers, which are small molecules that bind DNA covalently, forming inter-strand or intra-strand cross-links between specific dsDNA bases. Cisplatin irreversibly binds dsDNA and triggers apoptosis, or programmed cell death, and has been used in cancer therapy. This ligand creates intra-strand cross-links between guanine and neighboring guanine or adenine bases. It also creates inter-strand cross-links between guanine bases [50]. AFM stretching studies of λ-DNA [50-51] and synthetic dsDNA [50] with sequences p(dGdC)-p(dGdC), p(dAdC)-p(dGdT), and p(dG)-p(dC) reveal that high concentrations of cisplatin decrease the cooperativity of the melting transition and demonstrate slow binding kinetics. The absence of hysteresis in the presence of cisplatin suggests that the two single strands are in close proximity after the cross-linking, allowing them to re-anneal on the timescale of the experiment. Stretching curves of synthetic p(dAdT)-p(dAdT) dsDNA [50] did not exhibit any of these effects, confirming that cross-links only form with guanine bases. The drug psoralen is also a cross-linker, but it intercalates within the dsDNA base pairs as well, and its dual binding modes are discussed below, with other small molecules which exhibit multiple and complex binding modes.

2.2 Intercalators

Intercalators have flat aromatic rings that slide between adjacent dsDNA base pairs for π-electron system interactions, lengthening and unwinding dsDNA [52]. Intercalators stabilize dsDNA, and the well-studied dye ethidium is known as a classical intercalator. Initial force spectroscopy studies with ethidium [27] explored the nature of melting transition observed in DNA stretching experiments using optical fiber force sensors. In these experiments, saturated concentrations of ethidium (~25 μM) clearly demonstrate lengthening of the DNA molecule, but the force-extension curves do not display a melting transition or hysteresis.

AFM stretching experiments with λ-phage BstE II-digested DNA [51] and duplex poly(dG-dC) [53] in the presence of high concentrations of ethidium (~5-10 μM) reflect similar results. At lower concentrations (~1 μM), however, force-extension curves of λ-phage BstE II-digested DNA exhibit a melting transition at a higher force relative to that of DNA without drug, indicating dsDNA stabilization, and hysteresis between stretching and relaxation cycles [51]. Force spectroscopy studies with intercalators such as ethidium [54-59], YO [57, 59], psoralen [56], the psoriasis and herpes virus drug proflavin [56, 60], the chemotherapy drug daunomycin [57, 59], and high concentrations of berenil [56, 58] also illustrate increases in DNA extension and melting transition force at low concentrations, but no melting transition or hysteresis at high concentrations. Furthermore, proflavin studies show that these effects are independent of solution pH [60].

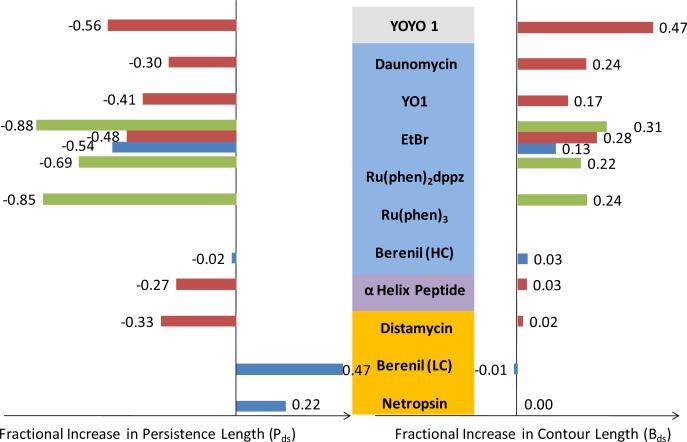

The first quantitative approach was to fit the force extension curves obtained in the presence of intercalators to the worm like chain (WLC) model [61], Equation (1). Fits of high concentration ethidium data at both low [58] and high force [59] limits indicate an increase in contour length and decrease in persistence length (Figure 3, blue and brown bars) relative to dsDNA in the absence of drug. The first experiments to observe non-equilibrium binding kinetics of mononuclear intercalators stretched DNA at various pulling rates in the presence of daunomycin [59]. DNA stretched to a maximum retention force was held at that extension to measure the force decay. Time constants obtained from these measurements are linearly dependent on the maximum retention force up to 45pN.

Figure 3.

Fractional increase in contour length (right) and persistence length (left) of the DNA-ligand complex for different drugs that exhibit a variety of binding modes, obtained from three types of fits to the WLC model (Equation (1)). Low force limit fits are shown in blue bars [58], high force limit fits are shown in brown bars [59, 66], and fits at drug saturation are shown in green bars [55]. Concentrations are relatively high (~1 μM) with the exception of saturated concentrations, which depends on the drug, and beneril, for which high concentration studies (HC) are at 3 μM and low concentrations studies (LC) are at 0.3 μM. The minor grove binders (drug names shaded yellow) show minor change in contour length, increase in persistence length in the low force limit and decrease in persistence length in the high force limit. Major groove binders (names shaded purple) show no change in contour length and decrease in persistence length. Intercalators (names shaded light blue) and bis-intercalator (names shaded gray) exhibits an increase in contour length and decrease in persistence length.

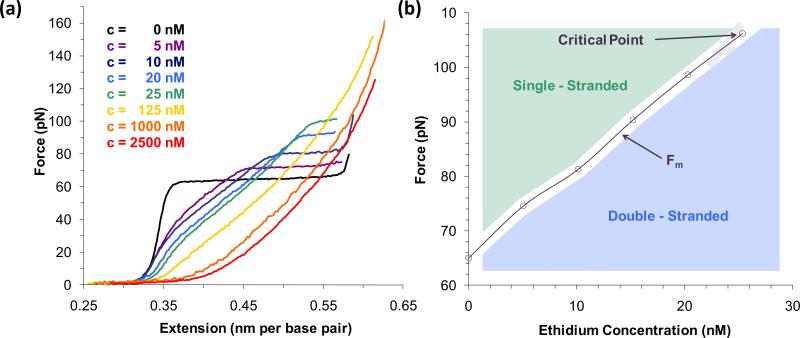

Rigorous concentration-dependent studies of ethidium with optical tweezers clearly illustrate that the DNA contour length increases with ethidium concentration, saturating at ~2.5 μM ethidium [54]. Although the melting force increases as a function of concentration, the transition plateau becomes progressively shorter as result of the DNA lengthening (Figure 4a). The phase diagram [54] in the force-extension-ethidium concentration space, which is analogous to PVT space for gas, showed a critical concentration for ethidium (~25nM) where phase separation between dsDNA and ssDNA becomes impossible (Figure 4b), which explains the disappearance of the melting transition at high concentration. Integrating the area under the dsDNA force extension curve in the presence and absence of ethidium provides the change in melting free energy due to the binding of ethidium, which is a function of concentration [54]. The results agree well with those from thermal melting experiments, demonstrating that increase in melting free energy corresponds to the increase in ethidium concentration.

Figure 4.

(a) DNA stretching curves in the presence of different ethidium bromide concentrations shows the increase in melting force, shortening of the melting transition with increasing concentration, and vanishing of the melting transition at a critical concentration around 25 nM. (b) The dependence of melting force on ethidium bromide concentration separates the two phases of the DNA (dsDNA shaded area in blue and ssDNA shaded area in green). The phase diagram shows that beyond 25 nM these phases cannot be distinguished by stretching experiments. Figures adopted from [12].

The site exclusion binding isotherm of McGhee and von Hippel relates the occupancy γ to the protein concentration c, for a protein with an equilibrium association binding constant K and binding site size n [62-63]:

| (4) |

Generally, the occupancy γ may refer to dsDNA (γds), ssDNA (γss), or intercalation (γint). For very large n, it may not be possible to obtain a DNA molecule fully saturated with ligand. However, the impact of this caveat decreases with ligand mobility rate, and the effect is unlikely to change experimental results within error.

Fractional occupancy γint, determined from change in DNA extension upon intercalation, fit to the McGhee von Hippel isotherm (Equation (4)) as a function of force yields K = 107 M-1 and n = 2 at F ≤ 10 pN and K = 1.5 × 107 M-1 and n = 1 at F ≥ 20 pN for ethidium [54]. The low force values agree particularly well with those obtained in bulk experiments. The high force value of n = 1 suggests that ethidium stacks between every base pair, which contradicts the traditional view that ethidium stacks only with every other base pair. It is possible that the conformation of the DNA backbone which excludes binding sites at low force may change as the DNA is held under higher tensions, allowing intercalation between every base pair.

Optical tweezers studies examining the concentration dependence of ethidium and daunomycin at low force (F ≤ 2pN) suggest that the contour length and persistence length of the drug-DNA complex increases with concentration until saturated binding, upon which the contour length remains constant and the persistence length decreases sharply to nearly that of drug-free DNA [64].

Optical tweezers experiments also examined the DNA binding properties of ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes Ru(phen)2dppz2+, Ru(phen)32+ and Ru(bpy)32+ [65]. The first two complexes clearly demonstrate the increase in melting force and contour length with high concentration that is characteristic of intercalation. The third complex, Ru(bpy)32+, does not intercalate at zero force. Fits of γint to the McGhee von Hippel binding isotherm (Equation (4)) suggest a binding site size of n = 3 for both intercalators, with binding constants of K = 3.2 (± 0.1) × 106 M-1 and K = 8.8 (± 0.3) × 103 M-1 for Ru(bby)2dppz2+ and Ru(phen)32+, respectively.

Single molecule studies propose a method of quantifying force-dependent intercalation which extrapolates the results to zero force, characterizing ligand binding to relaxed DNA [55]. This method is now widely used to analyze intercalation of small molecules. The force-dependent fractional occupancy of the DNA lattice ν is defined in terms of the binding site size n:

| (5) |

Thus ligand binding may be described in terms of fractional occupancy γ, which runs from 0 to 1, or fractional occupancy per base pair ν, which accounts for binding site size and therefore runs from 0 to 1/n. The fractional occupancy per base pair for intercalators, νint, at a given force F is:

| (6) |

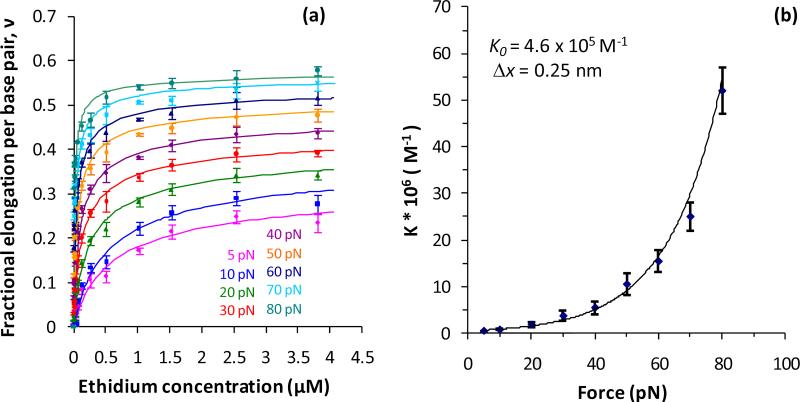

where bds(F,c) is the extension in the presence of the intercalator at concentration c, bds(F,0) is the extension in the absence of intercalator, and Bds is the DNA contour length in the absence of intercalator. This factional binding per base pair ν is fit to the McGhee von Hippel isotherm (Equations (4) and (5) combined) to obtain the equilibrium association constant KF and binding site size nF at a given force F (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) Fractional elongation per base pair (ν) as a function of ethidium bromide concentration c, fit to the McGhee von Hippel model at different forces F. (b) Force-dependent binding constants KF obtained from the fits shown in (a) yield the zero force binding constant K0 and the DNA lengthening upon a single intercalation event Δx.

The force F applied to stretch the DNA molecule reduces the free energy of intercalation ΔG0 by FΔx, where Δx is the dsDNA elongation upon a single intercalation event, leading to an exponential force dependence of the binding constant [55]:

| (7) |

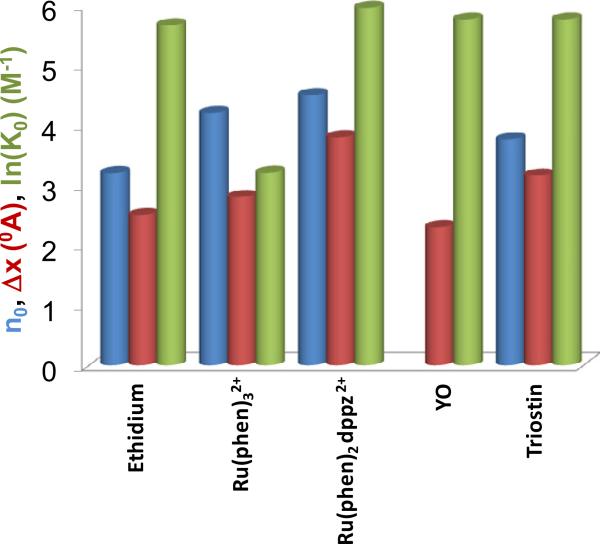

where K0 is the binding constant in the absence of the force, kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature (Figure 5b). Figure 6 presents K0, Δx, and n for ethidium [55], Ru(phen)2dppz2+ [55], Ru(phen)32+ [55] and YO [66].

Figure 6.

Binding site size n in base pairs (blue), lengthening upon a single intercalation event Δx in 0A (brown) and log of the zero force binding constant K0 in M-1 (green) estimated for ethidium, Ru(phen)32+, Ru(phen)2dppz2+, YO, and triostin using the method of Vladescu et al. [55] for molecules reported in [55, 66, 73].

Fits to the WLC model at saturated intercalator concentrations yield the persistence length, contour length, and elastic modulus of the drug-DNA complex at saturation. These results show that intercalator binding increases DNA contour length and decreases DNA persistence length (Figure 3, green bars). The saturated stretch modulus of the drug-DNA complex is reduced nearly five-fold relative to that of dsDNA in the absence of drug [55, 66].

Recent experiments with intercalator YO using the combined techniques of optical tweezers and fluorescence microscopy measure fluorescence intensity during DNA stretching [66]. Since YO molecules fluoresce only upon binding to dsDNA, the fluorescence intensity may be used to quantify intercalation. Fluorescence intensity and fractional elongation have the expected linear relationship, but with two regions of different slopes. This suggests a force-induced structural transition of the YO-DNA complex at ~0.14 fractional elongation at 100 nM YO. Additionally, fits to the WLC model (Equation (1)) provide the persistence length and contour length as a function of concentration for the YO-DNA complex. The results agree with those from the high force limit, demonstrating that the contour length increases with concentration, while the persistence length decreases.

2.3 Groove binders

The majority of molecules that bind in dsDNA grooves are positively charged, and thus binding is dominated by electrostatic interaction and assisted by hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions [51, 57]. Initial AFM stretching experiments explored the minor groove binding activity of berenil [51]. High concentrations of berenil results in dsDNA intercalation, and further investigations of groove binding used netropsin [56], an antibiotic that also exhibits antitumor and antiviral activity. Force-extension curves in the presence of netropsin, which is known to bind only in the minor groove of dsDNA, exhibit an increase in melting force similar to that observed in the presence of berenil at low concentrations. However, there was no broadening of the melting plateau, an effect which is only evident with berenil. To clarify this difference, AFM experiments examined the minor groove binder Hoechst 33258 [56]. These DNA stretching curves are similar to those in the presence of netropsin, without melting plateau broadening. Force extension curves in the presence of Hoechst 33258 do not depend on pH, and the slightly lower melting force at high pH (~10.5) relative to that at neutral pH (7.5) [60] may be attributed to the pH dependence of the DNA melting force [14].

Initial AFM stretching experiments with poly(dG-dC) dsDNA in the presence of the peptide distamycin-A found that the minor groove binder lowered the melting force to 50 pN [57]. Although this result contrasts with an expected increase in melting force, the discrepancy was attributed to the distamycin-A preference for AT-rich regions [57], although this observation remains unclear. Optical tweezers experiments stretching λ-DNA in the presence of distamycin-A measured an increase in the melting force [59], an observation consistent with results from other minor groove binding experiments. Therefore, molecules which bind in the minor groove are believed to increase the melting force and preserve melting transition cooperativity.

AFM experiments stretching poly(dG-dC) dsDNA examined two synthetic amphipathic peptides which bind to the major groove of dsDNA, an α-helix Ac-(Leu-Ala-Arg-Leu)3-NH-linker (linker:1,8-diamino-3,6-dioxaoctane) and 310-helix Ac-(Aib-Leu-Arg)4-NH-linker containing β-loop builder α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) [57]. Although the stretching curves of both major groove-binding peptides are similar to those of minor groove binders, both exhibit a decrease in melting transition cooperativity. DNA stretching experiments using optical tweezers in the presence of the α-helical peptide studied with AFM [59] and the major groove binder SYBR-Green I [67] confirm these characteristics of dsDNA major groove binding.

Fits to the WLC model (Equation (1)) for dsDNA-minor groove binding complexes with netropsin [58], berenil at low concentrations [58], and distamycin-A [59] did not indicate a change in contour length or persistence length in either the low or high force limits (Figure 3). In contrast, WLC model fits for the major groove binder α-helix Ac-(Leu-Ala-Arg-Leu)3-NH-linker (linker:1,8-diamino-3,6-dioxaoctane) did demonstrate an increase in contour length and decrease in persistence length (Figure 3).

2.4 Multiple and complex binding modes

Small molecules such as berenil and psoralen bind DNA with multiple binding modes, while molecules such as binuclear ruthenium complexes, YOYO, and triostin have complex modes such as threading intercalation and bis-intercalation. Berenil binds into the minor groove, favoring AT-rich regions, at low concentrations, but intercalates within the base pairs at high concentrations. AFM stretching experiments in the presence of berenil show minimal DNA lengthening, but demonstrate an increase in melting force at low concentration which resembles minor groove binding [51, 56]. At an order of magnitude higher concentration of berenil, the stretching curves exhibit loss of cooperativity and no hysteresis, resembling intercalators at high concentrations. A quantitative study fit force extension curves at varying berenil concentration to the WLC model (Equation (1)) in the low force limit [58]. The results reveal a significant increase in persistence length Pds at low berenil concentrations relative to that of dsDNA in the absence of drug. As berenil concentration increases, Pds decreases until it is less than the persistence length of dsDNA without ligands. This relationship indicates that the binding mode of berenil changes from minor groove binding, which is characterized by higher persistence lengths in the low force limit, to intercalation, which is characterized by low persistence lengths in the low force limit. The contour length Bds increases with berenil concentration, which is consistent with a change in DNA interaction from minor groove binding to intercalation.

Psoralen is a drug used in Psoralen Ultra Violet A (PUVA) therapy, which involves exposure of administered psoralen to Ultra Violet (UV) A light as treatment of specific skin diseases. The drug intercalates with dsDNA, then forms a covalent bond with pyrimidine in one DNA strand to form a mono-adduct. Exposure to UV A light results in a covalent bond on the other DNA strand for formation of a cross-link. Although exposure to UV B light may break cross-links, it does not affect the mono-adducts. DNA stretching experiments explore the binding mechanisms of psoralen, measuring the persistence length as a function of time in the presence of the drug when exposed to UV A light [68]. Fits of the DNA-drug stretching curves to the WLC model (Equation (1)) in the low force limit provide the persistence length Pds. Pds initially increases with exposure time as the drug begins to intercalate, then decreases in value as intercalation saturates. After this saturation point, Pds increases again to its maximum value after ~35 minutes, indicating formation of cross-links which make the complex more rigid. Exposing the drug-DNA complex to UV B results in a dramatic drop in Pds, indicating the breakage of cross-links, and the mono-adducts which remain are significantly less rigid.

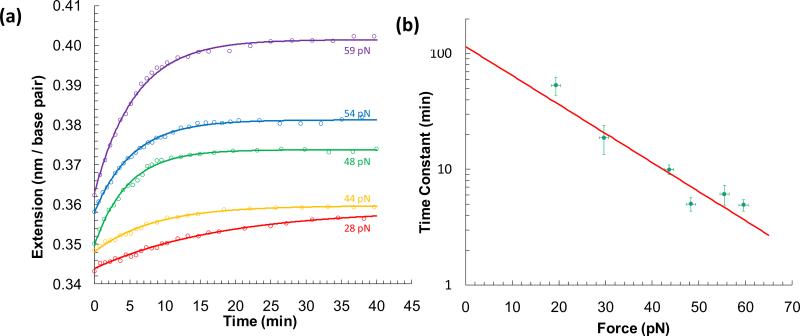

Binuclear ruthenium complexes are two covalently linked Ru(phen)2dppz2+ moieties, and they initially bind in the major grooves of dsDNA. These complexes then thread through the DNA bases, and the bidppz bridge intercalates between the dsDNA base pairs [69]. In order for this dumb-bell shaped binuclear ruthenium complex to thread, the dsDNA must melt so that the bulky end can slide through the unpaired bases and adopt the final threaded conformation. Although this requires hours to occur in traditional bulk experiments, single molecule DNA stretching in the presence of these complexes facilitates threading. Extrapolating the force-dependent kinetics measured then quantifies DNA binding kinetics in the absence of force. DNA that is stretched and held at a constant force in the presence of these complexes (Figure 7a) reveals a characteristic force-dependent time constant [70]. Applying force F favors the melted state by decreasing the melting free energy by FnΔx, and therefore increasing the probability of melting by [18]:

| (8) |

where n is the number of melted base pairs and Δx is the length increase due to conversion of dsDNA to ssDNA, a value which is expected to be 0.22nm in the linear approximation region [20]. This leads to an exponential dependence of the time constant on applied force:

| (9) |

where kBT is ~4.1pN-nm. Fits of the force dependence of these time constants (Figure 7b) yields that only one base pair must melt to thread the binuclear ruthenium complex. The extrapolation to zero force provided a time constant of 120 (± 30) min, which is the time constant associated with threading in the absence of force [70].

Figure 7.

(a) Extension measurements (open circles) as a function of time obtained at constant forces of 28 pN (red), 44 pN (yellow), 48 pN (green), 54 pN (blue) and 59 pN (purple) in the presence of threading intercalator ΔΔ-[μ-bidppz(phen)4Ru2]4+ and single exponent fits (solid lines) to these measurements. (b) Characteristic time constants (green circles) obtained from the fits in (a) for corresponding constant force measurements. Exponential dependence on force (fit, red line) yields the key result that only one base pair must melt in order for this molecule to thread through the DNA bases. Figures adopted from [70].

YOYO-1 is a bridged oxazole yellow (YO) dimer which stacks two aromatic ring systems into two intercalating sites, causing a clamp-like binding known as bis-intercalation. It can also bind in the DNA major groove at high concentrations. This dye is particularly useful to study the properties of DNA, since it is non-fluorescent in solution and highly fluorescent upon binding to dsDNA [71]. DNA stretching experiments with YOYO-1 show lengthening of dsDNA upon YOYO-1 binding, which is similar to other intercalators [57, 59, 66, 72]. In contrast to many intercalators, however, DNA stretching curves exhibit hysteresis during relaxation, and the dsDNA lengthening observed is strongly dependent on the velocity of stretching, which indicates slow binding kinetics [59, 66, 72]. When the DNA molecule is stretched to a maximum retention force, in an experiment designed to reach different fixed extensions, and allowed to relax in the presence of YOYO-1, the exponential decay of the retention force may be used to calculate the association time constant of YOYO binding [59, 66]. The results show that time constants are linearly dependent on the maximum retention force up to 60pN [59].

In experiments which combine optical tweezers with fluorescence microscopy, fluorescence intensity is used as a measure of the number of YOYO molecules bound [66]. The fluorescence intensity has a linear relationship with the fractional elongation, indicating that both quantities increase with the number of YOYO molecules bound. The equilibrium DNA lengthening may be obtained from this linear relationship. Furthermore, fits to the WLC model (Equation (1)) may be used to calculate the pulling rate-dependent contour length, persistence length, and stretch modulus. The results suggest that slow pulling rates, which are closer to equilibrium, yield the lowest persistence length and stretch modulus, but the highest contour length. The method of quantifying force-dependent intercalation kinetics developed by Vladescu et al. [55] was used to obtain the zero force binding constant K0 = 38.75 (± 1.28) × 105 M-1 and DNA lengthening upon single YOYO intercalation event, Δx = 0.095 (± 0.002) nm, although both quantities were inconsistent with results from bulk experiments.

A recent study shows that bis-intercalator triostin [73] exhibits properties similar to YOYO, with very slow kinetics. Thus the force extension curves obtained are non-equilibrium even at very slow pulling rates. Constant force measurements similar to those employed for threading intercalators [70] were used to obtain the equilibrium lengthening due to triostin binding dsDNA. Fractional elongation was calculated according to Equation (5), with a factor of 0.5 used to incorporate bis-intercalators. The method introduced by Vladescu et al. [55] for intercalators was used to analyze force-dependent kinetics in order to determine the binding site size n and binding constant K. The zero force binding constant of K0 = (5.8 ± 0.3) × 105 M-1 and DNA lengthening per intercalation event Δx = 0.316 nm were determined from the fits.

2.5 Classification of different binding modes

Although several studies discussed qualitative discrimination between intercalation, minor and major groove binding [51, 56-57], the first quantitative approach was with low force (F≤15pN) extension measurements obtained using optical tweezers [58], followed by fits of the data to the WLC model (Equation (1)) in the near-full extension limit [61]. Several more recent studies use the WLC in both the and low high force limits to obtain the contour length Bds and persistence length Pds of different small molecules (Figure 3).

The contour length obtained from fits to the WLC model in both low and high force limits provides the same insights. Minor groove binders [58-59] and major groove binders do not change the contour length, while intercalators [58-59, 66] and the bis-intercalator YOYO [59, 66] exhibit an increase in contour length for DNA-ligand complexes. Concentration-dependent studies on intercalators and bis-intercalators show that the contour length increases with the increase in concentration until saturation at a specific concentration [54-55, 65, 73].

Measurements of minor groove binders at low force (less than 15 pN) generally show an increase in DNA persistence length [58], whereas a measurement of minor groove binder Distamycin-A at higher force showed an increase in DNA persistence length [59]. Major groove binders cause a decrease in persistence length [58]. Concentration-dependent studies of intercalators show that the persistence length of the DNA-intercalator complex initially increases with concentration, dropping to the value of dsDNA [58, 64], and then dropping even lower at very high or saturated concentrations [55, 59, 66].

Other features that distinguish different binding modes qualitatively are the melting force, cooperativity of the transition and the hysteresis observed during relaxation. All of the dsDNA binding modes increase the melting force, as expected thermodynamically. The significant hysteresis observed in the presence of bis-intercalators and threading intercalators reflects slow dissociation kinetics [59, 66, 73]. Major and minor groove binders have similar effects on DNA stretching curves, but major groove binders decrease the cooperativity of the melting transition [57]. These results show that single molecule force spectroscopy is a useful method for quantitatively characterizing the thermodynamics and kinetics of small molecule interactions with DNA.

3 DOUBLE-STRANDED DNA BINDING PROTEINS

Force spectroscopy experiments on small molecules generally serve to assay length and force changes as ligands bind to double- or single-stranded DNA. Changes in the observed DNA force-extension curves indicate the mode and binding affinity. Proteins that preferentially bind to dsDNA also induce changes in DNA force-extension curves. In many instances, protein binding must be disrupted observe melting or extend the DNA-protein complex, as indicated by an increase in the observed melting force or by discrete increases in the measured DNA length. Protein binding may also alter the elasticity of the DNA backbone. dsDNA binding proteins often alter the overall organization of DNA in the cell. Examples of such DNA packaging proteins include histones that package DNA into chromatin in eukaryotic cells, as well as HU and H-NS proteins in Escherichia coli (E. coli). High mobility group (HMG) proteins facilitate the reorganization of packaged DNA in eukaryotic cells by altering DNA elasticity, which in turn allow other proteins access to the DNA. We discuss below single molecule force spectroscopy experiments that elucidate the mechanisms by which these proteins alter the biophysical properties of DNA to facilitate important cellular interactions.

3.1 Packaging DNA: Histones and chromatin

DNA is highly organized and compacted in the nucleus, interacting with histone proteins to form the basic higher order structure of the genome, known as the nucleosome core particle. First discovered in 1974 [74-76], the core particle is composed of pairs of the histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 [77-78]. Each histone is a small protein (~120 amino acids) that contains three D-helices connected by two loops, a motif known as the histone fold [79]. These highly conserved proteins, rich in basic residues, assemble to form an octamer in the shape of a rough disk. A length of 146 dsDNA base pairs wraps around this structure 1.65 times, forming a somewhat larger cylinder 11 nm in diameter and 5-6 nm in height [77]. The contacts between the histone core and the DNA include over 120 direct DNA-protein interactions [80], though the wrapped structure may include significant kinks and transient fluctuations [81]. This assembly of DNA and the octamer hub is known as the nucleosome core particle. Adjacent core particles may interact, stacking together to form a higher order structure known as chromatin [82-84]. The structure and stability of chromatin is driven by nucleosome stacking interactions, solution conditions and auxiliary histones that stabilize linker strands of DNA between adjacent core particles. The length of DNA between the start of adjacent core particles, known as the nucleosome repeat length, ranges from 165 to 212 base pairs, and determines the length of the linker DNA [82, 85]. Assembled chromatin fibers, roughly 30 nm in diameter, are further compacted in the cell into euchromatin and ultimately heterochromatin [78].

3.1.1 Fundamental interactions: Histones and nucleosomes

Early experiments on chromatin were not realized on the fully assembled structure, but on single strands of DNA wrapped around successive nucleosome core particles. The core particles were typically unstacked and separated by additional linker segments of DNA, the length of which depend upon the nucleosome repeat length. These experiments thus probed the stability of individual core particles, in a conformation sometimes referred to as beads on a string [86-92]. The ends of the assembly are tethered to polystyrene beads which are then manipulated in optical tweezers experiments. The results show small deformations in the extension curves at low forces that may be the result of nucleosomenucleosome interactions [89], while others have shown distinct unbinding ‘rips’ that begin at a threshold of ~ 20 pN, depending somewhat upon the solution conditions [86-88]. These rips, corresponding to DNA unwrapping from the nucleosome, show characteristic lengths of multiples of ~60 nm, corresponding to complete unwrapping and release of core particles [86]. Others have seen additional opening events with a smaller length scale, indicating stepwise breaking of histone contacts, opening of the core particle and ultimately the release of the octamer [87-88, 91].

3.1.2 Higher order interactions: Unraveling chromatin

Recent studies probe the higher order structure of assembled chromatin [93]. In these studies, 25 tandem repeats of 601 DNA, which localizes the chromatin to specific sequence locations [94-95], are used to facilitate the formation of a uniformly repeating structure. Two repeat lengths of 167 and 197 base pairs are used, which vary length of the linker segments between adjacent nucleosomes. In the presence of Mg2+, the assembled nucleosomes then reconstitute a 30 nm diameter chromatin fiber. The fiber, approximately 50 nm in length, is tethered to a 1 μm diameter magnetic bead and a microscope slide via additional linker DNA, raising the total contour length to 150 nm. Magnetic tweezers may pull this structure over several pN, with a sub-pN resolution. Here the instrument is configured with a force feedback mechanism, so that the tweezers act as a force clamp. When the chromatin fiber is unfolded to a string of DNA and nucleosomes, increases in extension are observed out to a length of ~750 nm. The applied tension is kept below the threshold force required for core particle disruption (~15 pN).

A key result reveals that chromatin, when constructed with a 197 nucleosome repeat length, displays a Hooke-like spring constant of 0.02 pN/nm (48,500 base pair phage λ DNA exhibits a spring constant of ~0.07 pN/nm). This spring constant is independent of the presence of linker histones H1 and H5, though there is some variability in the fitted parameters. However, a key difference in chromatin without linker histones is the observation of a plateau above 3 pN, where nucleosome–nucleosome interactions are reversibly broken. The length of the structure at the beginning of this transition suggests that the nucleosomes are stacked directly above each other, known as a one-start topology. When chromatin is constructed with a 167 nucleosome repeat length, the linker segments are correspondingly shorter. This causes an increase in the stiffness and length of these chromatin fibers. Furthermore, the structure observed just before the rupture of the nucleosome–nucleosome contacts consists of two twisted stacks, known as a two start topology. Thus the width of the assembled fibers is altered as well, an observation which AFM studies confirm, though the width may also be altered by the presence of linker histones [96]. However, it has been noted that the structure of the 30 nm fiber may be influenced by the techniques used to assemble the nucleosomes and there is some controversy about the exact structure of chromatin in vivo [97]. Given that the stacking interaction energy of the nucleosomes was estimated to be 13.8 kBT, molecular motors such as polymerases, known to typically stall at forces of 10-25 pN [87], can successfully force structural changes in chromatin, though the nucleosome presents strong forces that may stall such motors [98]. However, individual core particles, have been observed to partially and fully unwrap at much lower forces of several picoNewtons [99], suggesting that thermal fluctuations may play a substantial role in chromatin organization that remains poorly characterized. Nonetheless, these ongoing force spectroscopy experiments have provided insight into the protein-DNA contacts that stabilize the nucleosome core particle as well as the interactions between adjacent nucleosomes that favor the formation of chromatin.

3.2 Bending DNA and distorting chromatin: High mobility group proteins

High mobility group proteins are an abundant family of eukaryotic chromosomal proteins characterized by an array of DNA binding modes, including sequence-specific AT hooks and a variety of non-specific motifs [100-103]. The HMGB subgroup is distinguished by a single or double 80 amino acid domain that forms a box structure composed of three D-helices and a disordered tail. This simple structure is present during a variety of cellular processes which it may facilitate, including transcription [104-111], DNA repair [112] and immune response signaling [113-114]. These proteins are also known to facilitate DNA looping, a function also seen in HU [115-117]. A primary function of HMGB proteins is believed to be the disruption of chromatin through strong binding to dsDNA (possibly as a prelude to transcription) [100, 102, 104, 116, 118-121].

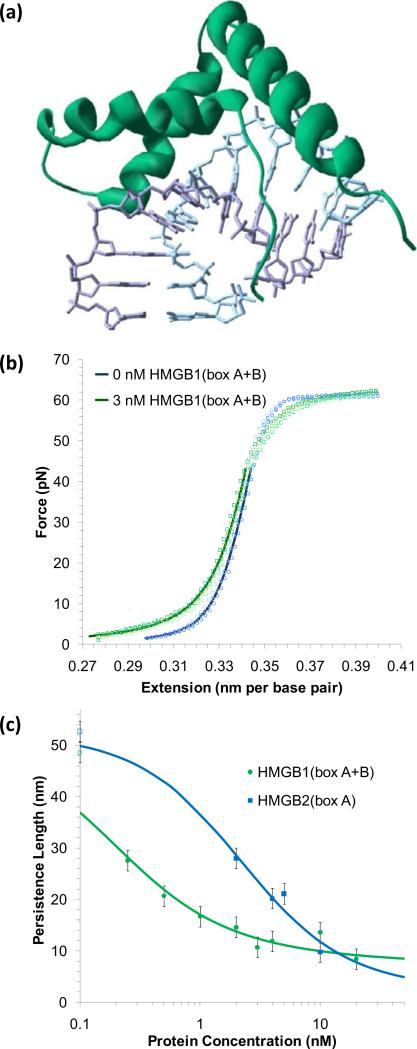

As the protein binds into the minor groove, interactions with the backbone occur through van der Waals contacts, direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds and partial intercalation. A strong, continuous bend is induced in the backbone, which has been measured to be ~111.1° for structures determined for the single box (shown in Figure 8a) [122-123], and 101.5 ± 9.1° for the double box motifs of HMGB like proteins [124]. In addition to measuring the bending angles induced by HMGB protein binding, optical tweezers experiments may determine the equilibrium association binding constant, distinguishing the binding strength from the bending ability.

Figure 8.

Distortions in the structure of DNA induced by HMGB family proteins. (a) The crystal structure of a single HMGB box motif is shown here for HMG-D from D. melanogaster [123]. Three helices and positively charged C-terminus become more ordered upon binding to DNA. The protein binds along the minor groove, intercalates into and induces a bend of ~ 111° over a region of ~ 7 base pairs (PDB code: 1QRV). Double box motifs are consecutively joined. (b) Extension data for a single molecule of phage-λ DNA (blue circles) and the same molecule in the presence of a solution containing 3 nM human HMGB1(box A+B) (green squares). Four separate extension cycles are shown, as are fits (solid lines) to the average, using the WLC model of Equation (1). Only forces below 45 pN are included for the fitted data, to minimize the effect of melting transition. Fits reveal a decrease in the persistence length of dsDNA from 46 ± 2 nm to 22 ± 2 nm as the protein is added. (c) The persistence length decreases continuously with the addition of single box HMGB2(box A) (blue) or HMGB1(box A+B) (green), and may be fit to the model of Equations (10) and (4) as described in the text. The equilibrium association binding constant per ligand is determined to be 5.9 (± 1.6) × 108 M-1 for HMGB1(box A+B) and 0.15 (± 0.06) × 108 M-1 for HMGB2(box A). Open symbols are persistence lengths from control fits to the same DNA molecules in the absence of protein [1, 12]

3.2.1 HMGB alters the elasticity of dsDNA

During a fully reversible cycle of extension and relaxation, dsDNA exhibits an entropic and elastic response until increasing force favors the stabilization of ssDNA. Upon extension, the entropic elasticity is characterized measuring its persistence length, Pds. Extension data for dsDNA have been fit to Equation (1) under a variety of temperature, pH and salt concentration conditions. Under typical conditions (10 mM Hepes, 100 mM Na+, pH = 7.5, T = 20 °C), as shown in Figure 8b, fits determine Bds = 0.340 ± 0.001 nm/bp, Pds = 48 ± 2 nm, and Sds = 1200 ± 100 pN [11, 125] Interpolated solutions to this model have given more accurate results over a wide range of forces. [126] Furthermore, the WLC model is limited to long sequences (n > 100 base pairs). [9, 127-129] Finally, the bends introduced by discrete protein binding events may distort the continuum of bending angles. However, long molecules (such as the 48 kbp λ DNA) with multiple bound proteins can be described by Equation (1), and changes to the fitted parameters characterize the effect of protein binding on dsDNA.

In the presence of just 3 nM of the two binding motif HMG protein HMGB1(box A+B), the extension data for dsDNA shows a clear change, in Figure 8b. Fits to Equation (1) give Bds = 0.339 ± 0.003 nm/bp, Pds = 22 ± 2 nm, and Sds = 939 ± 100 pN. While the contour length and stiffness show little definite change, the persistence length evinces a clear decrease. As protein binds to dsDNA, the persistence length decreases continuously, from a value for bare dsDNA PDNA to a value when dsDNA is fully covered PPR, as shown in Figure 8c. The observed persistence length Pds will vary according to the factional occupancy γds [130]:

| (10) |

The site exclusion binding isotherm of McGhee and von Hippel provides the occupancy γ (Equation (4)). To limit the number of free parameters, the binding site sizes are held fixed, using sizes determined in previous work [n = 7 for HMGB2(box A) and n = 18 for HMGB1(box A+B)] [122-124, 131]. Figure 8c shows the results of these fits, which yields an equilibrium association binding constant per ligand of 5.9 ± 1.6 × 108 M-1 for HMGB1(box A+B) and 0.15 ± 0.06 × 108 M-1 for HMGB2(box A).

The saturated dsDNA persistence length PPR is also determined from the fits. Assuming that the protein bending angles are induced at discrete sites, an average induced bending angle β may be estimated by [130, 132]:

| (11) |

The contour length at saturation BPR is determined from fits to Equation (1). A particular strength of this assay is that the affinity of protein binding and the degree of the protein-induced bend into the backbone may be deduced separately. Average induced bending angles for protein-DNA binding are β = 99 ± 9° for the single box protein HMGB2 and β = 77 ± 7° for the double box of HMGB1. Thee angles are in good agreement with measurements from other techniques [116, 124, 133-135].

3.2.2 Distributions of bending angles and enhanced DNA flexibility

The bending angles determined in optical tweezers experiments suggest an enhancement of the flexibility of dsDNA. Yet there remains a fundamental question about the nature of that flexibility. While the HU proteins described below appear to create a flexible hinge about the binding site [117], inducing a change in the local flexibility of DNA. The deduced structures for HMG proteins seem to indicate a fixed angle, or a static kink in the DNA generated by protein binding [123-124], which would enhance DNA flexibility through a mechanism of rapid binding and unbinding. Thus the observed distribution of bending angles will differ according to the binding mechanism. A protein that induces a flexible hinge will show a flat distribution of bending angles, as there is no single favored bending angle at the binding site. A distribution composed of a single peak about a well-defined fixed angle will characterize a static kink. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements are particularly well suited to measure the distributions of protein bending angles [136-139].

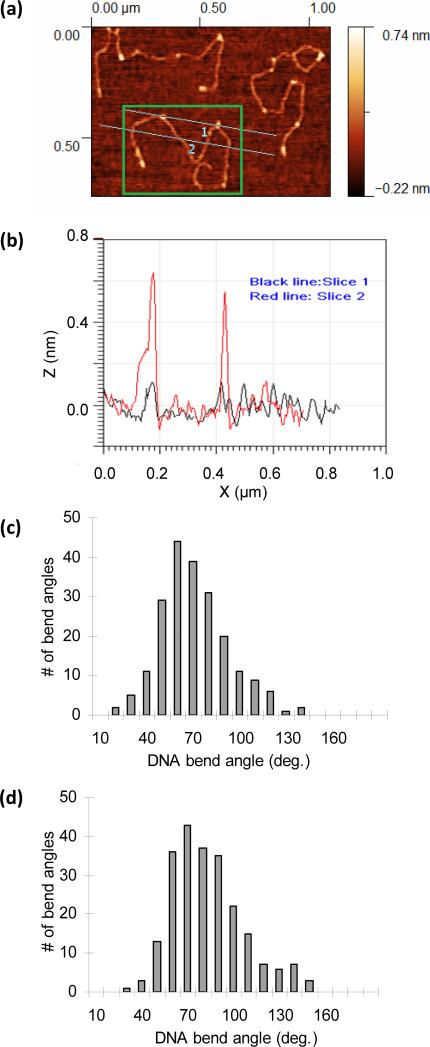

A caveat to AFM experiments is that interactions with the surface may influence the results. DNA–protein interactions are inherently three-dimensional, and the resulting complexes must be deposited upon a two-dimensional surface. If the surface interaction is strong, and the interaction with the substrate is relatively rapid, then the molecules are kinetically trapped and the observed images will have been significantly affected by the surface. If the molecules may approach the surface more slowly, an equilibrium may be established that has been shown to be remarkably unaffected by deposition [136, 140]. Simulations have also proven helpful, allowing the quality of deposition to be estimated for certain proteins [141]. Typical AFM images for pBR322 (4361 base pairs) DNA are shown in Figure 9a [142]. Bound HMG appears as individual bright spots associated with the DNA. The lighter color indicates a higher profile, as shown for two slices drawn through the image. The height profile along these images shown in Figure 9b indicates two protein binding events along the first slice, and that these correspond to the locations of the bright spots in Figure 9a. Although the second slice intercepts the DNA in several places, it crosses no spots and shows no assessable change in the height profile. Thus the spots indicate protein binding and the bend in the DNA backbone may be measured directly at these individual protein binding sites.

Figure 9.

Force microscopy reveals the distributions of bending angles. (a) Gradient surface scans of three DNA molecules in an HMG solution fixed to a mica surface and observed with an oscillating cantilever AFM. The green box frames a single DNA molecule and includes two cross slices. (b) Measured height profiles along cross slice one (black) and slice two (red). Along slice one, bound HMGB proteins are clear as bright spots in the surface image, which correlate to 0.6 nm changes in height. No proteins appear bound along slice two. The angle subtended by the backbone across these bound proteins may be measured directly. (c) Distribution of measured bending angles for HMGB1(box A+B) shows an average induced bending angle of 67 ± 1° (standard error). d) A larger average induced bending angle of 78 ± 1° may be deduced from the distribution for DNA in the presence of HMGB2(box A). The widths of the distributions for both proteins indicate a wide range of angles induced by protein binding [142].

Distributions for the single and double box motifs appear in Figure 9c and 9d. The average bending angles for HMGB1(box A+B) of 67 ± 1° for HMGB2(box A) of 78 ± 1° compare fairly well with the averages found from optical tweezers experiments. Both experiments show that the single box motif induces a greater bending angle into DNA versus the double box, and that the double box is not more effective at increasing the flexibility of dsDNA versus the single box. The standard deviations of these distributions (23° for the double box and 21° for the single box), however, signify that the binding mechanism created is neither a static kink nor a purely flexible hinge. In contrast to the results for HU discussed below, the results for both HMG motifs are peaked, though somewhat weakly. Thus HMG appears to alter the flexibility of DNA by a combination of two mechanisms. In the first, protein binding introduces local flexibility directly at the binding site. In the second, HMG induces local bends, and by rapidly binding and unbinding, alters the flexibility of the overall molecule.

3.2.3 Stabilizing dsDNA

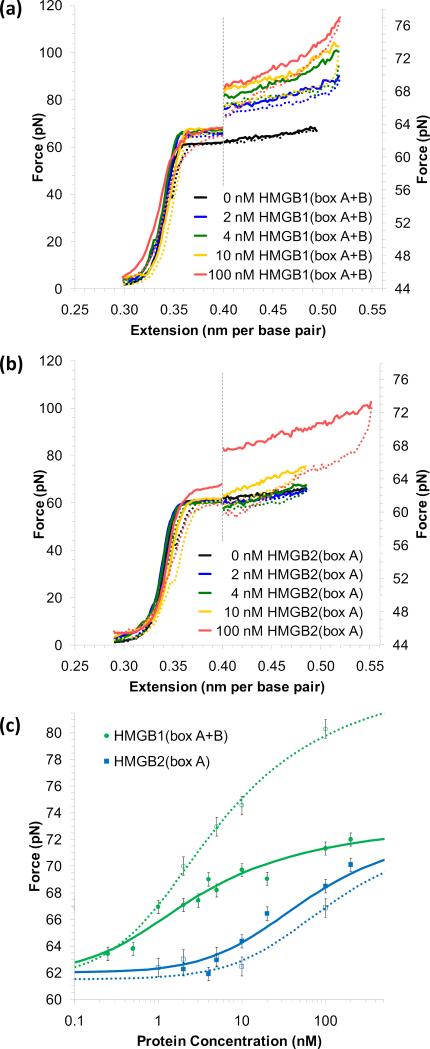

While optical tweezers experiments may characterize DNA binding with changes in elasticity, binding to dsDNA is also evident in the force-induced melting plateau. HMG binds and stabilizes dsDNA, as higher forces are required to melt DNA as shown in Figure 10a and 10b. Protein binding must be at least partially disrupted for melting to occur. In this instance, binding to dsDNA is characterized by the measured melting force, averaged over the extension range from 0.42 to 0.48 nm per base pair. As more protein is added, the average melting force increases, according to Figure 10c. The occupancy γds may be found by comparing the observed melting force Fm with the force measured in the absence of (Fm0) and fully saturated with protein (Fms) [143-144]:

| (12) |

Combining Equation (12) with the site exclusion model of Equation (4) gives the fits shown in Figure 10c and determines the equilibrium association binding constant per ligand to be 7.2 ± 1.7 × 108 M-1 for the double box HMGB1 and 0.28 ± 0.10 × 108 M-1 for the single box HMGB2.

Figure 10.

HMG proteins stabilize dsDNA. (a) Cycles of extension (solid lines) and relaxation (dotted lines) for DNA in the presence of no protein (black) and 2 nM (blue), 4 nM (green), 10 nM (yellow) and 100 nM (red) of human HMGB1(box A+B). The graph is split along the dotted line; data to the right is expanded along the scale shown. The observed melting force increases with escalating protein binding. Moderate hysteresis indicates some protein unbinding during the melting transition. (b) Stretching and relaxation data for DNA in the presence of no protein (black) and 2 nM (blue), 4 nM (green), 10 nM (yellow) and 100 nM (red) of rat HMGB2(box A). Stabilization of dsDNA requires greater amounts of the single box protein. Significant hysteresis is observed for high protein concentration, as protein–protein contacts must be dislocated for melting to occur. (c) The increase in the observed melting force as a binding assay for HMGB proteins. The averaged midpoint of the melting force plotted versus protein concentration for HMGB1(box A+B) (green) and HMGB2(box A) (blue). Error bars reflect instrumental uncertainty and standard deviations from a minimum of four individual extension curves. Fits are to the binding model of Equations (10) and (4), as described in the text. Fits determine an equilibrium association binding constant per ligand of 7.2 ± 1.7 × 108 M-1 for HMGB1(box A+B) and 0.28 ± 0.10 × 108 M-1 for HMGB2(box A).

The fact that the proteins exhibit such dissimilar binding characteristics is initially surprising, since the essential difference between the two proteins is simply the repetition of the box motif. The double box does exhibit a much stronger binding affinity, and the affinity should scale quadratically with the number of binding sites [145-147]. The discrepancy for the overall induced bending angles is particularly unexpected, as a structure containing two identical boxes might reasonably be expected to induce a much greater angle than the single box motif. Thus it is not correct to assume that the double box protein will simply exhibit the characteristics of two consecutive sites. The presence of the flexible linker may explain part of the difference, hindering the effective binding of box boxes simultaneously. Furthermore, at least one of the boxes must be disrupted to melt DNA, while DNA in the presence of the single box motif may be melted without protein dissociation until higher concentrations are reached. The fact that the single box motif must be dissociated in order to melt DNA only at high concentrations suggests that protein–protein interactions must be disrupted at high concentrations, in addition to protein-DNA interactions. Still higher concentrations have even been shown to induce filament formation in HMG [115, 148] and other proteins as well [117]. Thus, though both proteins stabilize dsDNA while enhancing local flexibility, HMGB1(box A+B) appears better suited toward the former while the single box motif of HMGB2(box A) appears to induce stronger bending.

3.3 The bacterial nucleoid: Comparisons to eukaryotes

In comparison to the strong organization of chromatin found in eukaryotes, in E. coli DNA is compacted into the nucleoid, a loose structure that is still poorly understood. Proteins that participate in DNA organization include a factor for inversion stimulation (FIS), histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS), integration host factor (IHF), and histone-like HU. While the roles of these proteins in bacteria appear to be analogous to those played by histones and HMGB proteins in eukaryotes, the structures of the bacterial nucleoid proteins share no similarities with the nuclear proteins of eukaryotes. Though these proteins (~100 amino acids) involved in DNA condensation have been identified, their exact function and relationships to each other are not well-understood. Additionally, many of the same proteins responsible for bacterial DNA condensation also function as transcription factors and possibly as part of other nucleoid processes [149-150]. Furthermore, the binding properties and functions of these E. coli proteins appear to overlap significantly, though subtle differences are known [149, 151-152]. FIS, IHF and H-NS appear to favor AT-rich segments, while IHF and FIS show some sequence specificity. HU, in contrast, appears to bind sequence-nonspecifically, but favors bent and damaged DNA [153]. It seems likely that experiments involving combinations of these proteins will be needed to fully elucidate their function. Yet single molecule experiments have given interesting insights into the behavior of these proteins, which present interesting comparisons with their eukaryotic counterparts.

3.3.1 IHF binds with sequence specificity

The sequence-specific IHF protein is a heterodimer of α-helices and β-sheets that bend dsDNA in two distinct kinks, producing an overall bend angle of nearly 180° [152, 154]. Though the protein has some non-specific DNA binding affinity, certain sequences are favored, possibly due to greater DNA flexibility in these regions [152]. Magnetic tweezers experiments have shown that IHF binding does serve to compact DNA, and that binding is quickly disrupted by even small increases in the tension along the DNA molecule [155]. While the structure of IHF appears similar to the histone-like HU protein, the proteins are not interchangeable, as both must be present to permit transcription [156]. Yet the specificity of IHF binding biases sites to non-coding regions of the bacterial genome, suggesting a regulatory function [149]. While the role of IHF in transcription is not certain, these results suggest that IHF serves a particular function, possibly facilitating loop formation necessary to the assembly of several structures during initiation [152].

3.3.2 HU and non-specific binding

The E. coli protein HU is another nuclear protein associated with binding to both double- and single-stranded DNA, and is often considered the bacterial analogue to histone-like proteins found in eukaryotes. HU resembles IHF in the appearance of an β-helical body capped by E-ribbon arms that bind into the minor groove of dsDNA [152-153]. HU binding produces a sharp bend in dsDNA, similarly to IHF, inducing bend angles between 105° and 140° [153-154]. However, unlike IHF, HU appears to show no sequence specificity. HU also binds strongly to bent or damaged (nicked) DNA, though binding to undistorted DNA has also been observed [117]. Much of the experimental data collected so far is on specifically damaged structures, which facilitates binding. This technique, commonly used to overcome the weak binding associated with non-specific binding proteins (including many X-ray and NMR structures), imposes important qualifiers on the known properties of HU.

Force spectroscopy experiments on HU bound undamaged DNA have combined magnetic tweezers studies and AFM imaging [117]. Both experimental approaches observe a change in the curvature of dsDNA at low protein concentrations below 100 nM. This is consistent with the role of enhancing DNA flexibility, also seen with the eukaryotic homologue HMG, as described above. While the measured persistence decreases, the distribution of measured angles is isotropic, in contrast to the peaked distributions for HMGB proteins. Thus HU appears to bind almost purely as a flexible hinge, inducing a highly variable bending angle when singly bound to DNA. At higher concentrations, optical tweezers experiments show an increase in the persistence length to over 100 pN, while AFM images show that the protein forms a fully rigid filament around DNA, an effect also seen with HMGB proteins as described above [148, 157]. Cooperative binding has been implicated as a way that HU may stabilize DNA. In this mode DNA is compacted in a histone-like manner [158-159]. Increases in the concentration of HU with respect to the concentrations of IHF have also been shown to inhibit the binding of the latter, as the cooperative binding mechanism apparently excludes IHF binding [156]. Thus an increase in concentration triggers a dramatic change in the interaction of HU with DNA, from a protein that may promote the flexibility of DNA in conjunction with other binding factors, to a protein that stabilizes and condenses dsDNA, excluding other proteins. Strikingly, the function of HU is significantly different from the function of IHF, though the structures bear strong similarities.

3.3.3 Non-specific H-NS binding dynamically bridges DNA

While HU influences higher order bacterial nucleoid structure by inducing changes in the flexibility of DNA, H-NS has been observed to directly bind two distinct DNA molecules together, forming a DNA-H-NS-DNA bridge. A novel assay tethers a pair of DNA molecules between four individually trapped beads, allowing the ends of each molecule to be separately manipulated. H-NS binds in multiple places between the two strands. Pulling on one of the free ends disrupts the bridges along the DNA, revealing the binding strength and the typical lengths between adjacent binding sites [160]. The results suggest an array of H-NS bridges that must serve to stabilize DNA and inhibit access by transcription factors. This regulatory role has been suggested for IHF and FIS as well [149]. However, the relatively low forces required to unbind these proteins suggest that that these structures may easily be overcome by other proteins or motors [151, 160]. Dynamic loop formation has also been observed in single DNA stretching experiments and visualized in AFM images, suggesting a model of flexible linkage that dynamically condenses the nucleoid, but does not deform bacterial DNA [161].

4 SINGLE-STRANDED DNA BINDING PROTEINS

The double-stranded, helical nature of duplex DNA protects and stabilizes the individual nucleic acid strands. However, these duplexes must melt into single-stranded DNA for cellular processes such as DNA replication, repair, and transcription, leaving exposed segments of ssDNA vulnerable to damage and degradation. Single-stranded binding proteins (SSBs) bind ssDNA to shield it from nucleases, prevent chemical degradation, and inhibit stem-loop and other secondary structure formation [162-163]. Furthermore, SSBs associate with cellular genome maintenance proteins such as polymerases, primases, helicases, and exonucleases, and may actively stimulate DNA replication, recombination, and repair through these interactions [164].

Organisms as diverse as viruses, bacteria, and mammals require SSBs for DNA replication [165]. SSBs therefore vary greatly in size, complexity, and binding mechanism. Bacteriophage SSBs bind DNA as monomers [166], bacterial SSBs are tetramers or dimers [167] with one known exception [168], and the eukaryotic SSB Replication Protein A (RPA) is a heterotrimer [169]. Despite this variation, the oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding (OB) fold [170] that binds ssDNA is conserved across SSBs in all domains of life [171]. Bacteriophages have among the simplest SSBs, with only one OB fold per monomer [163]. However, characterization of their DNA binding mechanisms has been relatively recent.

4.1 Bacteriophage SSB proteins

Although bacteriophage replication systems are well-studied models which have provided fundamental insights into the elaborate DNA replication process, the principal roles and interactions of each protein at the coordinated replication fork are not yet well-understood [172]. DNA replication in bacteriophage T7 is one of the simplest model systems, with a replisome comprised of T7 DNA polymerase, T7 helicase-primase, and SSB gene protein 2.5 (gp2.5). gp2.5 has 232 residues and preferentially binds ssDNA with a single OB fold in the core [166]. The protein forms a dimer in solution due to electrostatic binding of the highly acidic 26-residue C-terminus with the DNA binding site of another monomer, an interaction which occurs in the absence of DNA [166, 173-174]. gp2.5-Δ26C lacks this C-terminal tail, which is essential to gp2.5 interactions with the T7 DNA polymerase and helicase-primase at the replication fork [173, 175-176]. In addition to its predominant function as an SSB, gp2.5 facilitates complementary DNA strand annealing [177] and homologous base pairing [174, 177] more efficiently than SSBs from more complex replication systems such as those of bacteriophage T4 or E. coli [177-180].

Bacteriophage T4 is another excellent model replication system, and T7 gene 32 protein (gp32) is the most well-studied SSB. gp32 is a monomer which preferentially binds ssDNA and destabilizes the DNA duplex [164, 178]. The DNA binding site containing an OB fold is in the core of gp32 (residues 22-253), while the N-terminal domain (NTD, residues 1-21) is essential for highly cooperative binding to ssDNA, and the acidic C-terminal domain (CTD, residues 254-301) regulates DNA binding affinity and interacts with other replication proteins [181-183]. The C-terminal domain is absent in the mutant *I, which binds ssDNA with greater affinity than gp32. The preferential ssDNA binding revealed in bulk studies indicated that the dsDNA melting temperature (Tm) would decrease in the presence of both gp32 and *I, but thermal melting experiments measured this activity only for *I [178, 184-185]. Single molecule methods quantified the duplex destabilization activity of gp32 and *I, explaining these inconsistent DNA binding and thermal melting results [19-21].

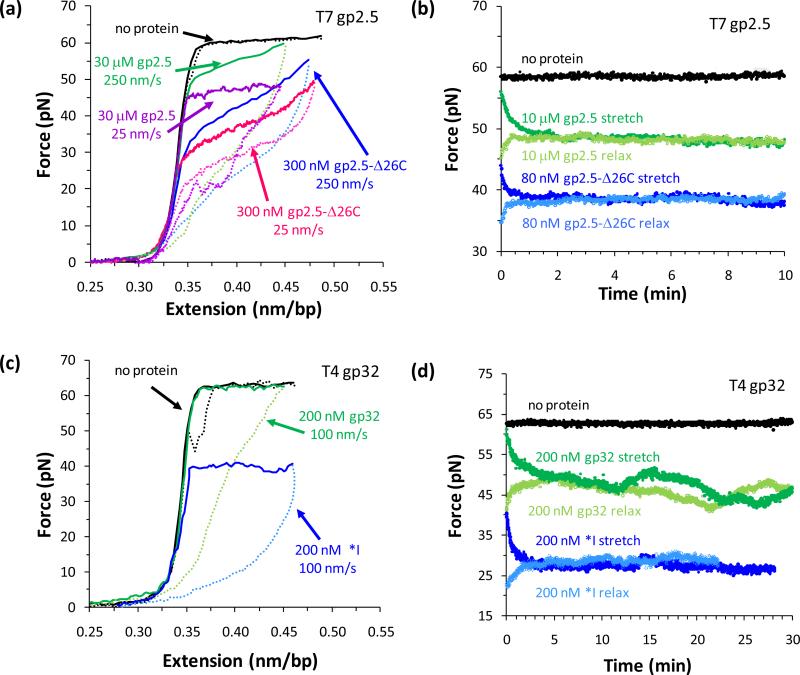

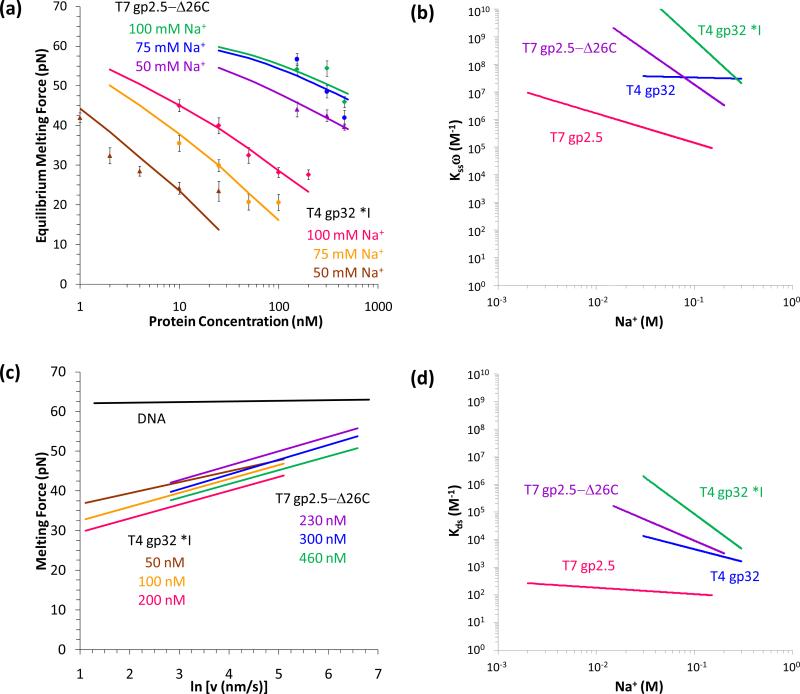

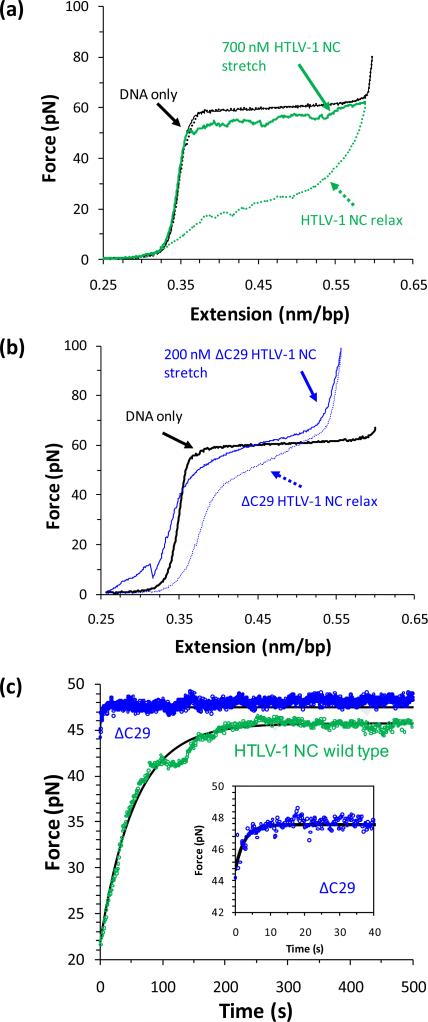

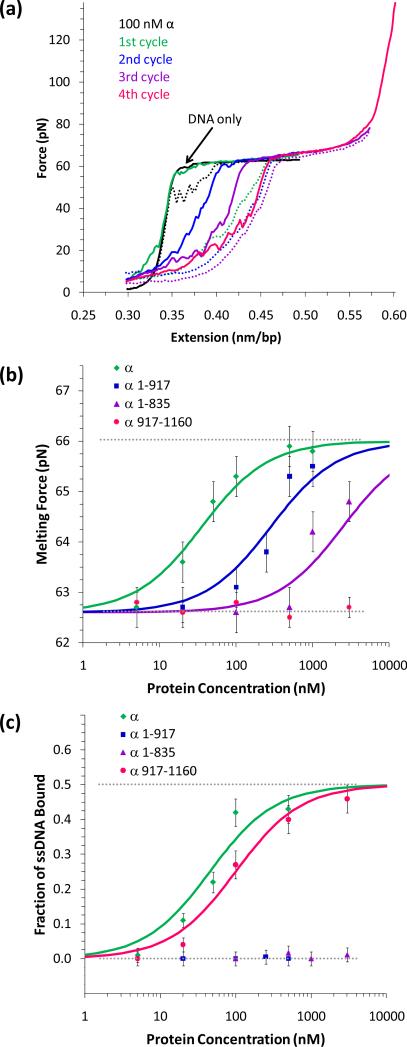

4.1.1 T7 gp2.5 and T4 gp32 preferentially bind ssDNA