Abstract

We examined the relationships between normal aging, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and brain levels of sex steroid hormones in men and women. In postmortem brain tissue from neuropathologically normal, postmenopausal women, we found no age-related changes in brain levels of either androgens or estrogens. In comparing women with and without AD at different ages, brain levels of estrogens and androgens were lower in AD cases aged 80 years and older but not significantly different in the 60–79 year age range. In male brains, we observed that normal aging was associated with significant decreases in androgens but not estrogens. Further, in men aged 60–79 years, brain levels of testosterone but not estrogens were lower in cases with mild neuropathological changes as well as those with advanced AD neuropathology. In male cases over age 80, brain levels hormones did not significantly vary by neuropathological status. To begin investigating the relationships between hormone levels and indices of AD neuropathology, we measured brain levels of soluble β-amyloid (Aβ). In male cases with mild neuropathological changes, we found an inverse relationship between brain levels of testosterone and soluble Aβ. Collectively, these findings demonstrate sex-specific relationships between normal, age-related depletion of androgens and estrogens in men and women, which may be relevant to development of AD.

1. Introduction

Advancing age is the most significant risk factor for the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Evans et al., 1989; Jorm et al., 1987; Rocca et al., 1986). One age-related change all women experience is the almost complete loss of their primary sex steroid hormone, the estrogen 17β–estradiol (E2) at menopause. Men also experience a robust age-related decrease in circulating levels of their primary sex steroid hormone testosterone (T), however this effect is much more gradual and typically less severe than E2 depletion in women (Morley et al., 1997; Vermeulen et al., 1996). The loss of sex steroid hormones during normal aging increases the risk of disease and dysfunction in hormone-responsive tissues (Baumgartner et al., 1999; Burger et al., 1998; Kleerekoper and Sullivan, 1995; Morley, 2001; Stampfer et al., 1990). Since the brain is a hormone-responsive tissue, age-related hormone depletion presumably results in diminished neuroprotective actions of hormones and an increased risk to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Pike et al., 2006; Rosario and Pike, 2008). In fact, epidemiological evidence has linked estrogen loss during menopause with an increased risk for the development of AD in women (Cholerton et al., 2002; Henderson, 2006). However, studies comparing E2 levels in women with and without AD have yielded conflicting results (Cunningham et al., 2001; Manly et al., 2000; Twist et al., 2000), as have studies evaluating the efficacy of hormone therapy in the prevention and treatment of AD (Espeland et al., 2004; Kawas et al., 1997; Rapp et al., 2003; Shumaker et al., 2004; Shumaker et al., 2003; Zandi and Breitner, 2003; Zandi et al., 2002).

In men, low circulating levels of total and free T have been associated with an increased risk for the development of AD (Hogervorst et al., 2003; Hogervorst et al., 2004; Hogervorst et al., 2001; Paoletti et al., 2004; Watanabe et al., 2004). While these studies established a relationship between androgens and AD, they did not distinguish whether low T levels are contributing to or resulting from the disease process. However, a longitudinal study found that the relationship between low T and AD precedes clinical diagnosis by several years (Moffat et al., 2004). Further, we previously reported that T levels in male brain are significantly reduced not only in cases of severe AD but also in cases with mild neuropathological changes, supporting the idea that low androgen levels are a risk factor for development of AD (Rosario, 2004).

In this study, we expanded our previous investigation into the relationship between brain levels of sex steroid hormones and AD neuropathological diagnosis. Specifically, we analyzed brain levels of testosterone (T), its active metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the weak estrogen estrone (E1), and its active metabolite the potent estrogen E2. We compared levels in postmortem brain samples from men and women both across normal aging and by AD neuropathological diagnosis. For male cases, we were also able to obtain sufficient cases with mild neuropathological changes consistent with very early stages of AD to evaluate hormone changes in transitional stages of AD pathogenesis. We report sex-specific relationships in levels of estrogens and androgens with both aging and AD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Human cases

Frozen postmortem brain tissue from midfrontal gyrus of neuropathologically characterized male and female cases, aged 50–97 years and predominantly Caucasian, was acquired from tissue repositories associated with Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers at the University of Southern California, University of California Irvine, University of California San Diego, and Duke University. To minimize the potential effects of hormone degradation, we included only cases with i) a postmortem interval (time lag between death and tissue processing) less than 10 hours, and ii) a storage period prior to hormone analysis of less than 6 years. Further, we excluded cases with a medical history that included conditions associated with altered androgen or estrogen levels, including renal disease, liver disease, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and use of hormone therapy.

All cases were either neuropathologically normal (i.e., lacking significant neuropathology of any type) or exhibited specifically AD associated neuropathology within defined Braak criteria (Braak and Braak, 1991) but lacking additional or mixed neuropathologies, including infarcts and other vascular pathology, Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body pathology, and hippocampal sclerosis. Clinical findings, which were available only in a subset of cases, were consistent with the neuropathological diagnoses. Female cases were divided into two groups according to neuropathological diagnosis: i) neuropathologically normal (Braak stage 0-I without evidence of degenerative changes; n=12, age range = 63 – 95 years, mean age = 81.3 ± 2.5 years, ii) AD (Braak stage V–VI with neuropathological diagnosis of AD in the absence of other neuropathologies); n=32, age range = 61 – 91 years, mean age = 74.3 ± 1.6 years. Female cases were analyzed both across ages and following stratification into two age groups, 60–79 years and ≥80 years (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Brain levels (mean ± standard deviation) of estrogens and androgens in female cases neuropathologically characterized as normal and AD, and grouped by age: all cases (56–94 years), 60–79 years, and ≥80 years.

| Sample size | Age, years | PMI, hours | T, ng/g WT | DHT, ng/g WT | E1, ng/g WT | E2, ng/g WT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases | NOR | 12 | 81.3 ± 2.5 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 0.65 ± 0.12 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 1.11 ± 0.27 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| AD | 32 | 74.3 ± 1.6* | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 0.54 ± 0.07 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.57 ± 0.2* | 0.07 ± 0.02 | |

|

| ||||||||

| 60−79 y | NOR | 6 | 71.3 ± 2.7 | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 0.63 ± 0.17 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 1.04 ± 0.4 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| AD | 24 | 71.3 ± 1.3 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | |

|

| ||||||||

| ≥80 y | NOR | 6 | 90.0 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 0.84 ± 0.12 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 1.53 ± 0.29 | 0.19 ± 0.04 |

| AD | 7 | 84.6 ± 1.6* | 4.2 ± 1.4 | 0.27 ± 0.11* | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.26* | 0.04 ± 0.07* | |

p < 0.05 relative to age-matched neuropathologically normal (NOR) group

Male cases were divided into three groups according to neuropathological diagnosis: i) neuropathologically normal (Braak stage 0-I, without evidence of degenerative changes, n=15, age range = 50 – 97 years, mean age = 80.6 ± 2.1, ii) mild neuropathological changes (MNC; Braak stage II–III and lacking neuropathology unrelated to AD); n=17, age range = 64 – 94 years, mean age = 79.5 ± 1.9, and iii) AD (Braak stage V–VI with neuropathological diagnosis of AD in the absence of other neuropathologies); n=33, age range = 60 – 89 years, mean age = 76.6 ± 1.4. Like the female cases, male cases were also analyzed both across ages and following stratification into two age groups, 60–79 years and ≥80 years (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Brain levels (mean ± standard deviation) of estrogens and androgens in male cases neuropathologically characterized as normal, mild neuropathology, and AD, and grouped by age: all cases (50–97 years), 60–79 years, and ≥80 years.

| Cond. | Sample size | Age, years | PMI, hours | T, ng/g WT | DHT, ng/g WT | E1, ng/g WT | E2, ng/g WT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases | NOR | 17 | 77.1 ± 2.3 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 0.77 ± 0.09 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.15 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| MNC | 17 | 79.5 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 0.57 ± 0.09 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.57 ± 0.16 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | |

| AD | 33 | 76.6 ± 1.4 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.07 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.11 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | |

|

| ||||||||

| 60−79 y | NOR | 7 | 71.1 ± 2.2 | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 1.03 ± 0.15 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.18 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| MNC | 7 | 71.9 ± 2.2 | 5.5 ± 1.3 | 0.55 ± 0.2* | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.2 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | |

| AD | 22 | 73.0 ± 1.2 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 0.54 ± 0.1* | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | |

|

| ||||||||

| ≥80 y | NOR | 8 | 87.2 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 0.29 ± 0.18 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.21 | 0.07 ± 0.04 |

| MNC | 10 | 85.0 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 0.42 ± 0.15 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.17 | 0.07 ± 0.07 | |

| AD | 11 | 84.6 ± 1.2 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.61 ± 0.17 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | |

p < 0.05 relative to age-matched neuropathologically normal (NOR) group

2.2 Hormone measurements

Steroid hormones, specifically unbound hormones since dissociation from binding proteins is necessary for entry into brain, were purified from frozen postmortem brain tissue (midfrontal gyrus) then quantified by radioimmunoassay (RIA) following organic solvent extraction and Celite column partition chromatography (Goebelsmann, 1979), as previously described (Rosario, 2004). In brief, frozen (−80°C) brain tissue was thawed, weighed, and homogenized in ice-cold PBS (3 ml PBS/g tissue). An aliquot of homogenate was taken for protein quantification and the remainder used for hormone quantification. 3H-labeled hormones (~500 cpm/tube) were included as internal standards to correct for procedural losses. The analytes were extracted with hexane:ethyl acetate (3:2) and separated from interfering steroids by use of Celite column partition chromatography with ethylene glycol as the stationary phase. DHT and T were eluted with 10% and 35% toluene in isooctane, respectively, whereas E1 and E2 were eluted with 15% and 40% ethyl acetate in isooctane, respectively. These assays have been shown to be sensitive, accurate, precise, and specific; inter-assay and intra-assay coefficient of variation were <10%. The sensitivity of the RIAs is 15 pg/ml for T, 8 pg/ml for DHT, 5 pg/ml for E1, and 3 pg/ml for E2. All collected data exceeded these detection limits, and there were a total of only four missing hormone values across all cases. All results were corrected for procedural losses and are reported as a fraction of starting tissue weight (protein correction yielded comparable results, data not shown).

2.3 Aβ ELISA

Soluble Aβ levels from postmortem tissue of normal and MNC cases were determined by ELISA as previously described (Nistor et al., 2007). Aβ was sequentially extracted in DEA buffer (50 mM sodium chloride, 0.2% DEA, and 1X protease inhibitor cocktail) using 1 ml buffer/100 mg wet weight tissue and centrifuged at 4°C at 16,000 × g for 30 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until assayed. Brain samples were run in triplicate on ELISA plates coated with a monoclonal anti-Aβ1–16 antibody (kindly provided by Dr. William Van Nostrand, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY) and detection was by monoclonal HRP conjugated anti-Aβ1–40 (MM32-13.1.1) and anti-Aβ1–42 (MM40-21.3.1) antibodies (kindly provided by Dr. Christopher Eckman, Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, Jacksonville, CA) (Das, 2003; Kukar, 2005; McGowan, 2005).

2.4 Statistical analyses

Linear regression was used to analyze the interaction between hormone levels (expressed as hormone amount per wet tissue weight) and age. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with age as the covariate followed by between group comparisons using the Fisher LSD test was used to compare differences in hormone levels by neuropathological status. Multivariate correlations followed by Spearman rank analyses were used to determine the relationship between hormones and hormone levels and soluble Aβ. Since age had an independent effect on soluble Aβ, partial correlations were performed to control for age.

3. Results

3.1 Brain levels of sex steroid hormones during aging and across neuropathological diagnoses in women

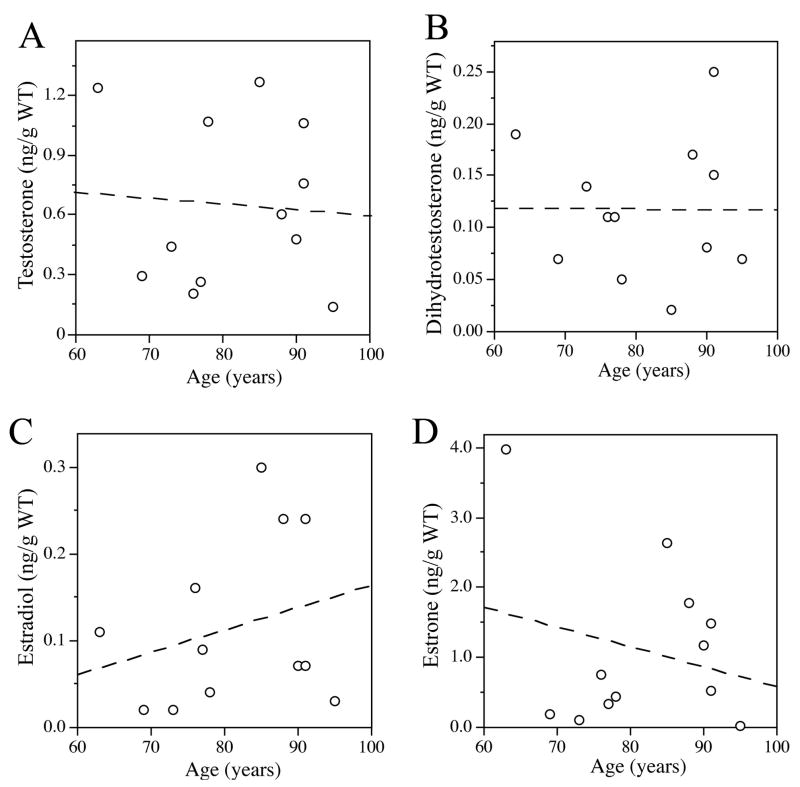

To investigate the effects of both age and the presence of AD on brain levels of sex steroid hormones in women, we first assessed levels of estrogens and androgens in frozen samples of midfrontal gyrus from neuropathologically normal postmenopausal women. We observed heterogeneity in the brain levels of the androgens, T and DHT, and the estrogens, E2 and E1, that were broadly distributed over approximately a five-fold range from lowest to highest values (Fig. 1). Of the four hormones measured, E1 was present at the highest mean levels, followed by T, E2, and DHT (Table 2). There were no statistically significant relationships between age and brain levels of any of the four studied hormones (T, r = −0.07, p = 0.82; DHT, r = −0.003, p = 0.99; E2, r = 0.27, p = 0.39; E1, r = −0.24, p = 0.46). To investigate potential relationships between hormones including the associations between precursors and metabolites, we performed correlations between hormone levels (Table 1). Levels of E1 showed significant positive associations with both its metabolite E2 and T. Conversely, T showed no relationship with its androgen metabolite DHT and only a nonsignificant association with its metabolite E2 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Brain levels of estrogens and androgens do not significantly change with age in postmenopausal women. Data show brain levels of sex steroid hormones versus age for (A) testosterone (r = −0.27), (B) dihydrotestosterone (r = −0.24), (C) estradiol (r = −0.07), and (D) estrone (r = −0.003) in all female cases (63–95 years, N=12) characterized as neuropathologically normal.

Table 1.

Correlations between estrogens and androgens in all female cases (63–95 years) neuropathologically characterized as normal.

| T, ng/g WT | DHT, ng/g WT | E1, ng/g WT | E2, ng/g WT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T, ng/g WT | 1.0 | _ | _ | _ |

| DHT, ng/g WT | 0.09 | 1.0 | _ | _ |

| E1, ng/g WT | 0.72* | 0.28 | 1.0 | _ |

| E2, ng/g WT | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.84* | 1.0 |

p < 0.05

To investigate whether brain levels of androgens and estrogens in postmenopausal women are associated with AD, we compared hormone levels in aged women that were diagnosed neuropathologically normal versus severe AD. Analyses performed on the entire female dataset showed no significant differences in brain levels of androgens between the normal and AD cases (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: T, F = 1.3, p = 0.30; DHT, F = 1.36, p = 0.28) (Table 2). However, we observed lower levels of estrogens in AD cases, relationships that reached statistical significance for E1 (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: E1, F = 3.8, p = 0.04) but not E2 (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: E2, F = 3.2, p = 0.08) (Table 2). To investigate whether these relationships vary by age group, we repeated these analyses after stratifying the cases into two age groups, 60–79 years and ≥80 years. In the relatively younger age group, we observed no significant differences between normal and AD cases in any hormone. In the ≥80 years group, we found that AD cases had significantly lower levels of E1, E2, and T (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: E1, F = 7.1, p = 0.02; E2, F = 7.0, p = 0.02; T, F = 10.2, p = 0.009) (Table 2).

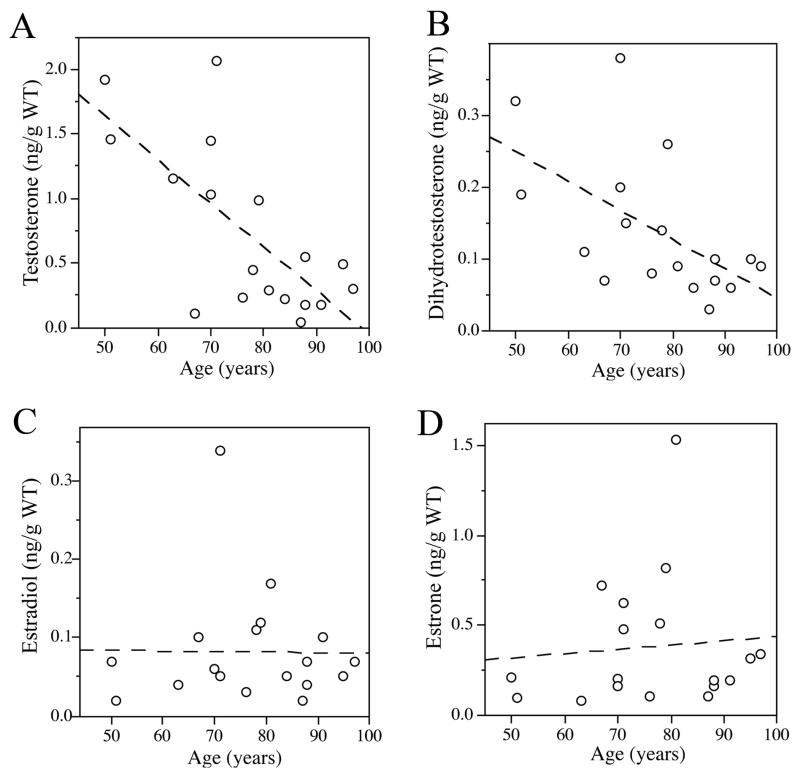

3.2 Brain levels of sex steroid hormones during aging and across neuropathological diagnoses in men

We previously reported an age-related decrease in brain levels of T but not E2 in men (Rosario, 2004). Extending our analyses of these cases, we found levels of not only T (r = −0.71, p < 0.01, Fig. 2A) but also DHT (r = −0.57, p = 0.01, Fig. 2B) were inversely correlated with age in neuropathologically normal male brains (N=18, age range 50–97 years). However, there was no relationship between age and brain levels of either E2 (r = −0.04, p = 0.96, Fig. 2C) or E1 (r = −0.09, p = 0.73, Fig. 2D). In contrast to our observations of hormone correlations in females, we observed in normal men that T levels strongly predict DHT levels but are not associated with either E1 or E2 levels (Table 3). Further, E1 shows a strong positive correlation with E2.

Figure 2.

Brain levels of androgens decrease with age in neuropathologically normal men. Data show brain levels of sex steroid hormones versus age for (A) testosterone (r = −0.71), (B) dihydrotestosterone (r = −0.57), (C) estradiol (r = −0.04), and (D) estrone (r = −0.09) in all male cases (50–97 years, N=17) characterized as neuropathologically normal.

Table 3.

Correlations between estrogens and androgens in all male cases (50–97 years) neuropathologically characterized as normal.

| T, ng/g WT | DHT, ng/g WT | E1, ng/g WT | E2, ng/g WT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T, ng/g WT | 1.0 | _ | _ | _ |

| DHT, ng/g WT | 0.87* | 1.0 | _ | _ |

| E1, ng/g WT | −0.15 | 0.05 | 1.0 | _ |

| E2, ng/g WT | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.86* | 1.0 |

p < 0.05

To investigate the relationships between sex steroids hormones and AD diagnosis in men, we compared brain hormone levels in aged men that exhibited no neuropathology, moderate to severe AD pathology, and mild neuropathological changes. In the full analysis of all male cases, we observed nonsignificant trends of lower T and higher E1 in AD cases, but no statistically significant differences in brain levels of androgens (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: T, F = 0.57, p = 0.56; DHT, F = 0.14, p = 0.87) or estrogens (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: E2, F = 0.37, p = 0.69; E1, F = 1.8, p = 0.17) across neuropathological status (Table 4). Analyses of data following stratification by age revealed brain levels of T in the 60–79 years group were significantly different across neuropathological diagnoses (ANCOVA, age as a covariate; F = 4.7, p = 0.02; Table 4). Specifically, T levels were lower in AD and mild neuropathology cases in comparison to neuropathologically normal men (Table 4). DHT followed a similar trend to that of T but did not reach statistical significance (ANCOVA, age as a covariate; F = 2.4, p = 0.25, Table 4). No changes in brain levels of E2 were observed between groups in the 60–79 age range (ANCOVA, age as a covariate; F = 0.22, p = 0.7, Table 4), although there was a trend towards increased brain levels of E1 in AD cases that did not reach statistical significance (ANCOVA, age as a covariate; F = 4.25, p = 0.06, Table 4). In male cases 80 years of age and older, we observed no significant differences in brain levels of either androgens (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: T, F = 2.5, p = 0.10; DHT, F = 2.6, p = 0.09; Table 4) or estrogens (ANCOVA, age as a covariate: E2, F = 0.4, p = 0.64; E1, F = 0.4, p = 0.66; Table 4).

3.3 Correlations between Aβ, age, and sex steroid hormones

Because previous findings have suggested that estrogens and androgens may be related to AD risk by regulating Aβ (Carroll et al., 2007; Rosario and Pike, 2008), we investigated whether brain levels of sex steroid hormones are associated with brain levels of Aβ prior to the development of AD. Levels of soluble Aβ 1–42 were not consistently detected at measurable levels using our ELISA system in neuropathologically normal cases (data not shown). Therefore, we limited our analyses to cases with mild neuropathological changes, for which only male cases were available. We observed a non-significant trend towards increased brain levels of Aβ with increasing age (Table 5). Notably, we found a significant negative correlation between levels of T and Aβ (Table 5). Because age and brain levels of T are significantly associated in men (Fig. 2), we performed partial correlations, to correct the T/Aβ relationship for age and the age/Aβ relationship for T. We found that correcting for T weakened the age/Aβ relationship (r = 0.12), but correcting for age only mildly reduced the strength of the T/Aβ relationship (r = −0.42). DHT, E1 and E2 showed modest negative correlations with Aβ1–42, although these relationships were weaker than the T relationship and were not statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlations between sex steroid hormones, age, and soluble levels of β-amyloid in male cases with ‘mild neuropathological changes’.

| Aβ42 | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.30 | 0.15 |

| T, ng/g WT | −0.49* | 0.044 |

| DHT, ng/g WT | −0.30 | 0.15 |

| E2, ng/g WT | −0.30 | 0.16 |

| E1, ng/g WT | −0.14 | 0.65 |

p < 0.05

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate the relationships between brain levels of sex steroid hormones in men and women during normal aging with and without AD. In postmenopausal women, we found no significant changes in brain levels of sex steroid hormones during normal aging. In men, we found normal aging was associated with significant decreases in the brain levels of the androgens T and DHT but no significant changes in the estrogens E2 and E1. Comparison of hormone levels between normal and AD cases revealed lower levels of estrogens and T in women, effects most apparent at advanced age. In men, T was significantly lower in AD cases than in neuropathologically normal cases but only within the 60–79 age range. Interestingly, within the same age group, we found that men with mild neuropathological changes consistent with early AD also showed significantly reduced T levels that were inversely correlated with brain levels of soluble Aβ.

Our analysis of sex steroid hormones in neuropathologically normal men and women represents the first analysis of brain levels of sex steroid hormones across aging. Numerous prior studies have evaluated age changes in sex steroid hormones in serum. In women, menopause is associated with a large decline in circulating levels of estrogens and androgens, however little change is observed following menopause (Militello et al., 2002; Paoletti et al., 2004; Riggs et al., 2002). Consistent with these findings, we did not observe significant changes in the levels of either estrogens or androgens in postmenopausal women across increasing ages from 63 to 95 years. We did observe a strong correlation between E1 and E2 in brain tissue from neuropathologically normal women, but only a weak, statistically insignificant correlation between T and E2, suggesting that E1 may be the primary prohormone responsible for E2 synthesis in the aged female brain.

In men, normal aging is associated with a gradual decrease in serum levels of T, typically beginning in the fourth decade, but no consistent change in serum levels of either DHT or estrogens (Kaufman and Vermeulen, 2005). Although circulating levels of sex steroid hormones are often predictive of tissue levels, brain levels of hormones can significantly differ from circulating levels due to the effects of sex hormone binding globulin, the presence in brain of steroid converting enzymes, and neurosteroidogenesis (Manni et al., 1985; Melcangi and Panzica, 2006; Schumacher et al., 2004; Stoffel-Wagner, 2001). In fact, our findings in men on age changes in brain levels of sex steroid hormones differ from established changes in serum levels. For example, whereas serum data in men indicate modest declines in both total T and free T with age (Harman et al., 2001; Kaufman and Vermeulen, 2005; Muller et al., 2003; Purifoy et al., 1981), our findings show a robust decline in brain T that reaches a nadir at approximately 80 years of age. Further, serum levels of DHT in men do not appear to decrease with age (Kaufman and Vermeulen, 2005) but our data show a significant inverse correlation between age and brain DHT levels. This parallel age-related decrease in brain levels of T and DHT is also reflected in the robust correlation between these hormones, indicating a strong precursor (T):product (DHT) relationship that was not observed in female brain. Interestingly, although T is converted into E2 by aromatase action in brain, we observed that E2 levels were not associated with T but rather with the estrogenic precursor E1.

An additional difference between established serum levels of sex steroid hormones and our data on brain hormone levels is the effect of gender. For example, while serum T levels are approximately 10-fold higher in normal aged men than in postmenopausal women (Militello et al., 2002; Paoletti et al., 2004; Rasmuson et al., 2002), we show very similar T levels in neuropathologically normal male and female brain. Further, serum levels of E2 are two- to three-fold higher in men than postmenopausal women (Militello et al., 2002; Paoletti et al., 2004), however in brain we observe negligible differences in E2 levels between men and women. There have been only a few prior studies that investigated brain levels of androgens and estrogens. These studies yielded results generally similar to ours, reporting comparable brain levels of E2 in neuropathologically normal men and women, and slightly higher brain levels of T in men compared to women (Hammond et al., 1983; Lanthier and Patwardhan, 1986).

In addition to examining the change in brain levels of sex steroid hormones across normal aging, we also investigated hormone changes associated with neuropathological diagnosis of AD. In women across all age groups, we found significantly lower E1 and a non-significant trend of lower E2 brain levels in AD cases compared with neuropathologically normal control cases. When these cases were stratified by age we found significantly decreased levels of both E2 and E1 in AD cases in the women over 80 years of age. This association of low estrogen and AD diagnosis is generally consistent with epidemiological evidence that identifies estrogen loss at menopause as a risk factor for the development of AD (Brinton, 2004; Henderson, 2006). Unclear is why estrogen levels were lower in the ≥80 age group but not the 60–79 age group, a time period one might predict would be more important if estrogen depletion contributes to AD pathogenesis. Prior studies comparing serum levels of estrogens in aged women with and without AD have been mixed, with reports of no differences (Cunningham et al., 2001), increased levels of E2 in AD subjects (Ravaglia et al., 2007, Hogervorst et al., 2003), and decreased levels of E2 in AD subjects (Manly et al., 2000; Schupf et al., 2006). Discrepancies in the literature may reflect low assay sensitivity for measurement of serum E2 (Hogervorst et al., 2003). This limitation is less of a concern with tissue analyses, since starting material can be increased to meet sensitivity criteria. There have been two prior studies that measured brain levels of estrogen in women. Similar to our findings, Yue and colleagues reported lower E2 levels in brain but not serum of postmenopausal women with AD (Yue et al., 2005), although Twist and colleagues found no changes in E2 between control and AD cases (Twist et al., 2000).

In men, our data suggest that any association between sex steroid hormones and AD involves androgens rather than estrogens. In the analyses of both the complete male dataset and the age-stratified groupings, neither E1 nor E2 differed significantly by neuropathological status. In contrast, T levels were lower in cases from severe AD and mild neuropathology consistent with early AD, although this effect was statistically meaningful only in the 60–79 age group. These data confirm and extend our prior observations that demonstrated low brain T in men with AD (Rosario, 2004). The only other published report that compared brain levels of T in men with and without AD reported a trend of lower T in AD cases (Twist et al., 2000), an effect that may have failed to reach statistical significance due to a small sample size and extended postmortem delay. Our observations of low T in AD men younger than age 80 is largely consistent with the literature on serum T and AD in men. That is, of the several studies that have linked low serum levels of T in men with a clinical diagnosis of AD, most report mean ages of less than 80 years (Hogervorst et al., 2003; Hogervorst et al., 2004; Hogervorst et al., 2001; Moffat et al., 2004; Paoletti et al., 2004; Watanabe et al., 2004). Further, one study reported that AD is associated with low T only in men less than 80 but not in those over age 80 (Hogervorst et al., 2004). The significance of the association between low T and AD specifically during the relatively early and middle phases of aging is hypothesized to reflect its potential contributing role in AD pathogenesis. Consistent with this notion, longitudinal data show that serum T levels in men are reduced several years prior to the clinical diagnosis of dementia (Moffat et al., 2004). Although the reasons why age 80 appears to be a significant time point are not known, it is interesting to note that our data in neuropathologically normal men indicate that 80 is the approximate age when brain levels of T reach their lowest point.

Of particular interest is the significance to AD pathogenesis of low brain estrogens in women and low brain androgens in men. One possibility is that age-related depletion of estrogens and androgens may contribute to AD pathogenesis. Ample evidence demonstrates that estrogens have numerous beneficial neural actions relevant to a protective role against AD, including regulation of cognition, neuron viability, and accumulation of Aβ (Brinton, 2004; Wise, 2006). Thus, relatively low levels of estrogens are predicted to make the brain more vulnerable to AD. Recent experimental evidence suggests parallel protective actions of androgens in male brain. That is, androgens are positively associated with cognition (Cherrier et al., 2005; Janowsky, 2006), neuroprotection (Pike et al., 2008), and reduction in Aβ levels (Rosario and Pike, 2008). Why we observe sex-specific relationships between hormones and AD, although brain levels of hormones are similar between the two sexes, is not clear. One possibility is that estrogens and androgens induce sex-specific neural actions relevant to AD. For example, spine density in female rodent hippocampus is positively regulated by estrogens (Woolley, 1999), whereas in males androgens but not estrogens are involved (Leranth et al., 2003). Similarly, estrogen reduces Aβ levels in female rodents (Petanceska et al., 2000; Carroll et al., 2007), but androgens are more important than estrogens in Aβ regulation in males (Ramsden et al., 2003).

In this study, we began initial evaluation of the relationship between AD pathology and brain levels of hormones by measuring brain levels of soluble Aβ in male cases with mild neuropathological changes. Our observations of a negative correlation between brain levels of T and Aβ are consistent with the hypothesis that loss of androgen may contribute to the development of AD. Our findings also agree with recent studies that have found significant inverse relationships in the blood levels of T and Aβ in men suffering from memory loss (Gillett et al., 2003) as well as prostate cancer patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy (Almeida and Papadopoulos, 2003; Gandy et al., 2001). In conjunction with findings in rodent (Ramsden et al., 2003; Rosario, 2006) and cell culture (Gouras et al., 2000; Yao et al., 2008) models demonstrating androgen regulation of Aβ, our results in mild neuropathology cases suggest that one important consequence of low brain levels of T in at least some men is an increased potential for Aβ accumulation, which in turn may precipitate the development of AD.

Despite the value and potential significance of these data, there are also several limitations. First, this study was limited in sample size. We collected cases from four different tissue repositories and evaluated more cases than what is typical for similar studies. However, stratification of cases to examine differences across neuropathological states at different ages resulted in some groups with fewer than 10 cases. Consequently, some analyses were underpowered to statistically evaluate subtle differences. In addition, we were not able to include a female ‘mild neuropathological changes’ group because of insufficient sample size resulting from our strict exclusion and inclusion criteria. While our strict criteria limited sample size and thus certain analyses, they also strengthened our findings by eliminating many variables that may affect hormone levels. Nonetheless, there are some variables that we were unable to control for and may have affected hormone levels, including body mass index (Tan and Pu, 2002; Seftel, 2006) and use of psychoactive drugs (Meador-Woodruff and Greden, 1988). The inclusion of the ‘mild neuropathological changes’ group in males allowed us to indirectly control for a range of other potential confounding factors since these cases are unlikely to display the late life conditions and agonal state associated with advanced AD.

In summary, this study describes the relationships between estrogen and androgen levels in male and female brain both during normal aging and in the presence of AD. Interestingly, the data show that mean levels of sex steroid hormones are remarkably similar in male and female brain although there is a wide range of observed values. This variability suggests the possibility that relatively high or low levels of hormones may be associated with differential risk to neural disorders including AD. In fact, our data show that, within defined age ranges, AD in women is associated with low estrogens whereas AD in men is associated with low androgens. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that normal, age-related loss of sex steroid hormones is one of a large number of factors that are associated with AD and may contribute to its pathogenesis. Further study will be necessary to clarify the potential roles of other brain hormones and the extent to which therapeutic maintenance of hormone levels in brain may reduce AD risk.

Acknowledgments

Tissue was obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers at the University of Southern California (AG05142), University of California Irvine (AG16573), University of California San Diego (AG05131), and Duke University Kathleen Price Bryan Brain Bank (AG05128). The authors thank Dr. Wendy Mack for assistance with statistical analyses. This study was supported by grants from the NIA (AG23739 to CJP), Alzheimer’s Association (IIRG-04-1274 to CJP), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS05214301 to ERR).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement. The authors have no financial, personal or other conflicts related to this study. This study was performed under a human subjects protocol approved the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almeida TA, Papadopoulos N. Progression model of prostate cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;222:211–22. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-328-3:211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner RN, Waters DL, Gallagher D, Morley JE, Garry PJ. Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;107 (2):123–36. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1991;82 (4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton RD. Impact of estrogen therapy on Alzheimer’s disease: a fork in the road? CNS Drugs. 2004;18 (7):405–22. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger H, de Laet CE, van Daele PL, Weel AE, Witteman JC, Hofman A, Pols HA. Risk factors for increased bone loss in an elderly population: the Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147 (9):871–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Pike CJ. Progesterone and estrogen regulate Alzheimer-like neuropathology in female 3xTg-AD mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27 (48):13357–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2718-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Matsumoto AM, Amory JK, Asthana S, Bremner W, Peskind ER, Raskind MA, Craft S. Testosterone improves spatial memory in men with Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2005;64 (12):2063–8. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165995.98986.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholerton B, Gleason CE, Baker LD, Asthana S. Estrogen and Alzheimer’s disease: the story so far. Drugs & Aging. 2002;19 (6):405–27. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CJ, Sinnott M, Denihan A, Rowan M, Walsh JB, O’Moore R, Coakley D, Coen RF, Lawler BA, O’Neill DD. Endogenous sex hormone levels in postmenopausal women with Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86 (3):1099–103. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Howard V, Loosbrock N, Dickson D, Murphy MP, Golde TE. Amyloid-beta immunization effectively reduces amyloid deposition in FcRgamma−/− knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23 (24):8532–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08532.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Shumaker SA, Brunner R, Manson JE, Sherwin BB, Hsia J, Margolis KL, Hogan PE, Wallace R, Dailey M, Freeman R, Hays J. Conjugated equine estrogens and global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291 (24):2959–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, Scherr PA, Cook NR, Chown MJ, Hebert LE, Hennekens CH, Taylor JO. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in a community population of older persons. Higher than previously reported. JAMA. 1989;262 (18):2551–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandy S, Almeida OP, Fonte J, Lim D, Waterrus A, Spry N, Flicker L, Martins RN. Chemical andropause and amyloid-beta peptide. JAMA. 2001;285 (17):2195–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.17.2195-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillett MJ, Martins RN, Clarnette RM, Chubb SA, Bruce DG, Yeap BB. Relationship between testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin and plasma amyloid beta peptide 40 in older men with subjective memory loss or dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5 (4):267–9. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebelsmann U, Bernstein GS, Gale JA. Serum gonadotropin, testosterone, estradiol, and estrone levels prior to and following bilateral vasectomy. 1979:165. [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Xu H, Gross RS, Greenfield JP, Hai B, Wang R, Greengard P. Testosterone reduces neuronal secretion of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97 (3):1202–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond GL, Hirvonen J, Vihko R. Progesterone, Androstenedione, Testosterone, 5a-dihydrotestosterone and androsterone concentrations in specific regions of the human brain. J Steroid Biochem. 1983;18 (2):185–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(83)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86 (2):724–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson VW. Estrogen-containing hormone therapy and Alzheimer’s disease risk: understanding discrepant inferences from observational and experimental research. Neuroscience. 2006;138 (3):1031–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Testosterone and gonadotropin levels in men with dementia. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2003;24 (3–4):203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E, Bandelow S, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Low free testosterone is an independent risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39 (11–12):1633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E, Williams J, Budge M, Barnetson L, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Serum total testosterone is lower in men with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2001;22 (3):163–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E, Williams J, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Measuring serum oestradiol in women with Alzheimer’s disease: the importance of the sensitivity of the assay method. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;148 (1):67–72. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1480067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowsky JS. Thinking with your gonads: testosterone and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10 (2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Henderson AS. The prevalence of dementia: a quantitative integration of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;76 (5):465–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JM, Vermeulen A. The decline of androgen levels in elderly men and its clinical and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2005;26 (6):833–76. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawas C, Resnick S, Morrison A, Brookmeyer R, Corrada M, Zonderman A, Bacal C, Lingle DD, Metter E. A prospective study of estrogen replacement therapy and the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neurology. 1997;48 (6):1517–21. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleerekoper M, Sullivan JM. Osteoporosis as a model for the long-term clinical consequences of the menopause. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1995;38 (3):181–8. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(95)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukar T, Murphy MP, Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Weggen S, Smith TE, Ladd T, Khan MA, Kache R, Beard J, Dodson M, Merit S, Ozols VV, Anastasiadis PZ, Das P, Fauq A, Koo EH, Golde TE. Diverse compounds mimic Alzheimer disease-causing mutations by augmenting Abeta42 production. Nature Med. 2005;11:545–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanthier A, Patwardhan VV. Sex steroids and 5-en-3 beta-hydroxysteroids in specific regions of the human brain and cranial nerves. J Steroid Biochem. 1986;25 (3):445–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leranth C, Petnehazy O, MacLusky NJ. Gonadal hormones affect spine synaptic density in the CA1 hippocampal subfield of male rats. JNeurosci. 2003;23 (5):1588–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01588.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Merchant CA, Jacobs DM, Small SA, Bell K, Ferin M, Mayeux R. Endogenous estrogen levels and Alzheimer’s disease among postmenopausal women. Neurology. 2000;54 (4):833–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni A, Pardridge WM, Cefalu W, Nisula BC, Bardin CW, Santner SJ, Santen RJ. Bioavailability of albumin-bound testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61 (4):705–10. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-4-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan E, Pickford F, Kim J, Onstead L, Eriksen J, Yu C, Skipper L, Murphy MP, Beard J, Das P, Jansen K, Delucia M, Lin WL, Dolios G, Wang R, Eckman CB, Dickson DW, Hutton M, Hardy J, Golde T. Abeta42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron. 2005;47 (2):191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH, Greden JF. Effects of psychotropic medications on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 1988;17 (1):225–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcangi RC, Panzica GC. Neuroactive steroids: old players in a new game. Neuroscience. 2006;138 (3):733–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Militello A, Vitello G, Lunetta C, Toscano A, Maiorana G, Piccoli T, La Bella V. The serum level of free testosterone is reduced in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2002;195 (1):67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, Kawas C, Blackman MR, Harman SM, Resnick SM. Free testosterone and risk for Alzheimer disease in older men. Neurology. 2004;62 (2):188–93. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE. Androgens and aging. Maturitas. 2001;38 (1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM, Patrick P, Morley PM, Stauber PM, Vellas B, Baumgartner RN, Garry PJ. Longitudinal changes in testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone in healthy older men. Metabolism. 1997;46 (4):410–3. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M, den Tonkelaar I, Thijssen JH, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Endogenous sex hormones in men aged 40–80 years. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;149 (6):583–9. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nistor M, Don M, Parekh M, Sarsoza F, Goodus M, Lopez GE, Kawas C, Leverenz J, Doran E, Lott IT, Hill M, Head E. Alpha- and beta-secretase activity as a function of age and beta-amyloid in Down syndrome and normal brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28 (10):1493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti AM, Congia S, Lello S, Tedde D, Orru M, Pistis M, Pilloni M, Zedda P, Loddo A, Melis GB. Low androgenization index in elderly women and elderly men with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2004;62 (2):301–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000094199.60829.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petanceska SS, Nagy V, Frail D, Gandy S. Ovariectomy and 17beta-estradiol modulate the levels of Alzheimer’s amyloid beta peptides in brain. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35 (9–10):1317–25. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ, Nguyen TV, Ramsden M, Yao M, Murphy MP, Rosario ER. Androgen cell signaling pathways involved in neuroprotective actions. Horm Behav. 2008;53 (5):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ, Rosario ER, Nguyen TV. Androgens, aging, and Alzheimer’s disease. Endocrine. 2006;29 (2):233–41. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:29:2:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purifoy FE, Koopmans LH, Mayes DM. Age differences in serum androgen levels in normal adult males. Human Biol. 1981;53 (4):499–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden M, Nyborg AC, Murphy MP, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Golde TE, Pike CJ. Androgens modulate beta-amyloid levels in male rat brain. J Neurochem. 2003;87 (4):1052–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, Gass ML, Stefanick ML, Lane DS, Hays J, Johnson KC, Coker LH, Dailey M, Bowen D. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289 (20):2663–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmuson S, Nasman B, Carlstrom K, Olsson T. Increased levels of adrenocortical and gonadal hormones in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2002;13 (2):74–9. doi: 10.1159/000048637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravaglia G, Forti P, Maioli F, Bastagli L, Montesi F, Pisacane N, Chiappelli M, Licastro F, Patterson C. Endogenous sex hormones as risk factors for dementia in elderly men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62 (9):1035–41. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ. Sex steroids and the construction and conservation of the adult skeleton. Endocrine Rev. 2002;23 (3):279–302. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca WA, Amaducci LA, Schoenberg BS. Epidemiology of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1986;19 (5):415–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario ER, Carroll JC, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Pike CJ. Androgens regulate the development of neuropathology in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26 (51):13384–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2514-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario ER, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Pike CJ. Age-related testosterone depletion and the development of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2004;292 (12):1431–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1431-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario ER, Pike CJ. Androgen regulation of beta-amyloid protein and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57 (2):444–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Robert F, Carelli C, Gago N, Ghoumari A, Gonzalez_Deniselle MC, Gonzalez SL, Ibanez C, Labombarda F, Coirini H, Baulieu EE, De_Nicola AF. Local synthesis and dual actions of progesterone in the nervous system: neuroprotection and myelination. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2004;14(Suppl A):S18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupf N, Winsten S, Patel B, Pang D, Ferin M, Zigman WB, Silverman W, Mayeux R. Bioavailable estradiol and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease in postmenopausal women with Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2006;406 (3):298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seftel AD. Male hypogonadism. Part I: Epidemiology of hypogonadism. International journal of impotence research. 2006;18 (2):115–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, Rapp SR, Thal L, Lane DS, Fillit H, Stefanick ML, Hendrix SL, Lewis CE, Masaki K, Coker LH. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291 (24):2947–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, Hendrix SL, Jones BN, Assaf AR, Jackson RD, Kotchen JM, Wassertheil_Smoller S, Wactawski_Wende J. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289 (20):2651–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Menopause and heart disease. A review. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;592:193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel-Wagner B. Neurosteroid metabolism in the human brain. European Journal of Endocrinology/European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2001;145 (6):669–79. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1450669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan RS, Pu SJ. Impact of obesity on hypogonadism in the andropause. International journal of andrology. 2002;25 (4):195–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twist SJ, Taylor GA, Weddell A, Weightman DR, Edwardson JA, Morris CM. Brain oestradiol and testosterone levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2000;286 (1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM, Giagulli VA. Influence of some biological indexes on sex hormone-binding globulin and androgen levels in aging or obese males. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81 (5):1821–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.5.8626841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Koba S, Kawamura M, Itokawa M, Idei T, Nakagawa Y, Iguchi T, Katagiri T. Small dense low-density lipoprotein and carotid atherosclerosis in relation to vascular dementia. Metabolism. 2004;53 (4):476–82. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM. Estrogen therapy: does it help or hurt the adult and aging brain? Insights derived from animal models. Neuroscience. 2006;138 (3):831–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Effects of estrogen in the CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9 (3):349–54. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M, Nguyen TV, Rosario ER, Ramsden M, Pike CJ. Androgens regulate neprilysin expression: role in reducing beta-amyloid levels. J Neurochem. 2008;105:2477–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue X, Lu M, Lancaster T, Cao P, Honda S, Staufenbiel M, Harada N, Zhong Z, Shen Y, Li R. Brain estrogen deficiency accelerates Abeta plaque formation in an Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102 (52):19198–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505203102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi PP, Breitner JC. Estrogen replacement and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2003;289 (9):1100–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi PP, Carlson MC, Plassman BL, Welsh_Bohmer KA, Mayer LS, Steffens DC, Breitner JC. Hormone replacement therapy and incidence of Alzheimer disease in older women: the Cache County Study. JAMA. 2002;288 (17):2123–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]