Abstract

Background & Aims

HCV patients who fail conventional interferon-based therapy have limited treatment options. Dendritic cells are central to the priming and development of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immunity, necessary to elicit effective viral clearance. The aim of the study was to investigate the safety and efficacy of vaccination with autologous dendritic cells loaded with HCV-specific cytotoxic T cell epitopes.

Methods

We examined the potential of autologous monocyte derived dendritic cells (MoDC), presenting HCV-specific HLA A2.1-restricted cytotoxic T cell epitopes, to influence the course of infection in six patients who failed conventional therapy. Dendritic cells were loaded and activated ex vivo with lipopeptides. In this phase 1 dose escalation study, all patients received a standard dose of cells by the intradermal route while sequential patients received an increased dose by the intravenous route.

Results

No patient showed a severe adverse reaction although all experienced transient minor side effects. HCV-specific CD8+ T cell responses were enumerated in PBMC by ELIspot for interferon-γ. Patients generated de novo responses, not only to peptides presented by the cellular vaccine but also to additional viral epitopes not represented in the lipopeptides, suggestive of epitope spreading. Despite this, no increases in ALT levels were observed. However, the responses were not sustained and failed to influence the viral load, the anti-HCV core antibody response and the level of circulating cytokines.

Conclusions

Immunotherapy using autologous MoDC pulsed with lipopeptides was safe, but was unable to generate sustained responses or alter the outcome of the infection. Alternative dosing regimens or vaccination routes may need to be considered to achieve therapeutic benefit.

Keywords: Cell therapy, ELIspot, interferon-γ, epitope, therapeutic

Introduction

Recovery from HCV infection is associated with a diverse and sustained T cell response while a weak, transient T cell response is associated with the development of persistence [1]. Several factors may contribute to HCV persistence. Low levels of viral antigen produced during acute infection may provide insufficient stimulus for an effective immune response. To support this, a higher proportion of patients with clinical acute hepatitis C clear the infection compared with patients with subclinical infection [2,3] although this may be related to the vigor of the immune response, assuming that symptomatic disease is a surrogate marker of this. Several HCV proteins are immunosuppressive and block signalling pathways critical for sensing viral RNA and initiating immunity [4], and mutations in B and T cell epitopes result in antibody and T cell escape [5,6]. Other mechanisms include down regulation of NK cell activity and a failure of the innate immune response to elicit an effective adaptive immune response [7,8], functionally impaired T cells leading to lack of effector cell function [9], impaired dendritic cell (DC) function resulting in ineffective T cell priming [10], phenotypic exhaustion of HCV-specific hepatic CD8+ T cells [11] and an imbalance in the Treg/Teffector cell ratio [12].

Individuals with specific HLA class II haplotypes are more likely to recover from acute HCV infection [13] suggesting a critical role for CD4+ helper T cells, important for DC priming of CD8+ T cells and in CD8+ T cell memory development. In acute HCV infection, virus-specific CD8+ T cells can be detected by tetramer staining but fail to achieve full lytic and IFNγ-secreting capacity [14]. Patients who control the infection show maturation of CD8+ T cell memory sustained by progressive expansion of IL-7R+ CD8+ T cells [15]. We [10] and others [15] interpreted these data as indicative of impaired priming of the anti-viral T cell response and a major factor leading to persistence. Priming of CD8+ T cells in the absence of T cell help or by impaired DC, is likely to lead to a low frequency of functional T cells, a consistent characteristic of HCV infection [9].

DC, professional antigen presenting cells, process and present antigen to prime naïve T lymphocytes, but require activation (maturation and licensing) to be efficient [16]. Due to their central role in T cell activation, immunotherapy with antigen-loaded DC has been proposed as a novel means to eliminate tumours and infectious agents by boosting the patient’s existing immune response or by generating immunity de novo, after ex vivo manipulation of the cells followed by infusion. Due to the paucity of DC in the blood, DC used in immunotherapy trials are generally differentiated from autologous CD34+ stem cells or CD14+ monocytes [10] because the number of DC infused in a single dose is greater than that which can be harvested from blood. The in vitro differentiation of CD14+ monocytes into monocyte derived dendritic cells essentially resembles the in vivo development of DC from monocytes [17]. Thus, although, several studies reported a reduced frequency or impaired function of DC in the blood of HCV carriers, other studies failed to confirm these findings [18–20]. We hypothesised that treatment with DC, differentiated from precursors ex vivo, are less likely to be compromised by HCV infection.

For the phase 1 clinical study described here, we used MoDC that were matured and antigen loaded with lipopeptides based on HCV-specific CD8+ T cell epitopes. The rationale for the study was that 50% of the Caucasian population is HLA A2 positive and several HLA A2-specific CTL epitopes have been described. We have previously established (i) that these HCV lipopeptides matured human MoDC efficiently in vitro [21], (ii) that murine DC pulsed with the lipopeptides showed no evidence of toxicity in mice even at a dose multiple of 40-fold used in this trial [22] and (iii) the generation of HCV lipopeptide-loaded human DC in serum free medium (SFM) [23]. Here we report on the potential of autologous MoDC, loaded and matured ex vivo with a pool of HCV lipopeptides, to influence the outcome of chronic HCV infection.

Patients and methods

Human subjects

Subjects were recruited from December 2006 to January 2008. Eligible subjects included adults who had previously failed IFN-based therapy, aged 18–75 years with repeated serological evidence of HCV genotype 1 infection and/or quantifiable serum HCV RNA >600 IU/ml (Roche Cobas® TaqMan® HCV Test, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), compensated liver disease (Child-Pugh score <7) and histological findings consistent with chronic hepatitis C on a previous liver biopsy. Exclusion criteria included: non-HCV genotype 1 infection, hepatitis B virus and/or human immunodeficiency virus infection, history of decompensated liver disease, evidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, causes of chronic liver disease other than HCV, therapy with any systemic antiviral, antineoplastic, or immunomodulatory agent within the preceeding 6 months, pregnancy or breast feeding, neutrophil count <1500 cells/mm3, platelet count <90,000 cells/mm3, haemoglobin concentration <120 g/L in women or <130 g/L in men, serum creatinine level >1.5 times the ULN, history of autoimmune disease or any severe chronic or uncontrolled disease, current or recent drug or alcohol abuse, and unwillingness to provide informed consent. Patients with clinical and/or histologic evidence of cirrhosis were also excluded. The trial was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the Alfred Hospital, Melbourne. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient and the study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in a priori approval by the HREC. Six patients were enrolled and their details described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics | Patient No. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Sex M/F | F | M | M | M | M | M |

| Age (yr) | 50 | 46 | 61 | 44 | 48 | 39 |

| Caucasian (Yes/No) | Y es | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| HCV genotype | 1a/b | 1 | 1a/b | 1a | 1a/b | 1b |

| HCV RNA titre (×106 IU/ml) |

0.56 | 1.10 | 0.22 | 2.10 | 2.49 | 2.82 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) |

49 | 89 | 63 | 135 | 51 | 42 |

| Metavir stage | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Child – Pugh score | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 139 | 153 | 167 | 166 | 155 | 150 |

| Platelets (×109) | 169 | 158 | 269 | 212 | 296 | 158 |

| Lymphocytes (× 109/L) | 1.59 | 1.44 | 2.91 | 1.71 | 1.96 | 1.68 |

Eligible patients were chosen on the basis of HLA A2-positivity determined by flow cytometry and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The trial was approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration of Australia (TGA-the Australian equivalent of the FDA) under the Clinical Trial Exemption scheme (similar to an FDA IND). Product collection, manufacturing, and release testing took place under the auspices of the Centre for Blood Cell Therapies (CBCT) which currently holds a TGA GMP manufacturing licence.

Apheresis

Leukocytes were derived by apheresis using a COBE Spectra apheresis machine equipped with a COBE Spectra leukocyte collection set (Caridian BCT, Lane Cove, Australia). The product was generated from the equivalent of 2 times the patient total blood volume with an ACD-A:whole blood ratio of 1:12. The final volume of the product was usually ~200ml with a red cell packed cell volume of <5%. Apheresis and all subsequent cell manipulation procedures were performed within the CBCT.

Lipopeptide-loaded DC

Clinical grade CD14+ monocytes were isolated using CD14 microbeads in the CliniMACS instrument (MiltenyiBiotec), cultured in Vuelife Teflon culture bags (CellGenix, Freiburg, Germany) in CellGro® SFM containing GM-CSF and IL-4 for 4 days, as described [23]. The immature DC were matured in the same medium containing 6µM lipopeptides and 1µg/ml prostaglandin E2 over a period of 48h [23], washed and 1 × 107 cells resuspended in 1 ml 0.9% sodium chloride injection BP, 10% human serum albumin (HSA) (CSL Ltd, Melbourne) for ID infusion and 1–5 × 107 cells resuspended in 100 ml of the same diluent for IV infusion. The lipopeptides, described previously [21–23], were based on HLA A2-restricted CD8+ T cell epitopes associated with clearance of acute HCV infection, linked individually to a universal Th epitope (Th), KLIPNASLIENCTKAEL, and the lipid moiety, Pam2Cys. The structure of similar lipopeptides has been described [24]. The six lipopeptides were pooled in equimolar concentrations. The CD8+ T cell epitope peptides, termed CTL1-6 are;

| CTL1, HCV core 132 | DLMGYIPLV |

| CTL2, HCV core 35 | YLLPRRGPRL |

| CTL3, HCV core 177 | FLLALLSCLTV |

| CTL4, HCV NS3 1406 | KLVALGINAV |

| CTL5, HCV NS4B 1807 | LLFNILGGWV |

| CTL6, HCV NS4B 1851 | ILAGYGAGV |

The mature lipopeptide-loaded DC were generated in a functionally closed sterile culture system. The initial DC dose used fresh cells and additional doses used cells, previously cryopreserved in vapour phase liquid nitrogen. All DC preparations were confirmed as sterile and with an endotoxin level of <5.0 EU/kg.

DC infusions and patient analysis

One week after apheresis, the time required to prepare the DC, the ID infusion was injected into the groin region and the IV infusion given over a period of 30 min. Each patient remained under observation for approximately 18h as an in-patient. Patients who received >1 dose of DC were infused at two weekly intervals (Table 2). Thereafter, blood samples were taken from each patient on days 1–3, weekly for one month then every two weeks for a period of three months. PBMC for analysis of the CD8+ T cell responses were prepared by Ficoll-Paque PLUS (Amersham, Castle Hill, Australia) density gradient centrifugation. ELIspot analysis of peptide-stimulated PBMC was performed as described [23] by stimulation with peptide pools representing the complete HCV polyprotein (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) or the above CTL1-6 peptides. A dominant influenza A virus peptide epitope (GILGFVFTL) was used as an ELIspot control. Anti-HCV core antibody titres were measured by an in-house assay [25] and circulating cytokines by cytokine bead array (Biorad, Sydney). Endotoxin was measured using the USP <85> Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) gel clot method.

Table 2.

Escalating dose schedule.

| Patient # | Infusion 1 | Infusion 2 | Infusion 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV dose units* (1 dose unit = 1×107 cells) | |||

| 1 | 1 | - | - |

| 2 | 1** | 1 | - |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 4 | 1 | 5 | - |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | 5*** (2) | 5*** (2) | 5*** (2) |

Each IV dose unit was accompanied by a standard intradermal infusion of 1×107 cells.

Multiple doses were given at two weekly intervals.

This scheduled dose was not infused because the desired number of DC could not be generated – see results. Instead, two dose units were infused at each time point by the intradermal route only.

Results

Preparation and analysis of clinical scale monocyte-derived DC

Our previous laboratory scale studies showed that the average proportion of CD14+ monocytes in human PBMC was approximately 20% [23], well within the reported normal range of 8–30%. Prior to patient enrolment, the Australian regulator, the TGA, requested that three training runs be performed under full clinical conditions to determine the release criteria for the final product viz. HCV lipopeptide-loaded DC, were achieved. The results were performed with three healthy volunteers (Table 3, Vol 1 – 3) and showed that the release criteria of >90% purity of CD14+ monocytes and >75% viability of DC were achieved, regardless of variability in the proportion of CD14+ monocytes in the apheresis product (10.6 – 27.1%; average 19.7%). The additional criteria (Table 3) are preferred criteria that, although relevant for assessment of DC function, were not considered decisive to result in a non-compliant product if any individual criterion was unmet.

Table 3.

Phenotypic markers of monocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells

| Marker | Vol 1 |

Vol 2 |

Vol 3 |

Pt 1 |

Pt 2 |

Pt 3 |

Pt 4 |

Pt 5 |

Pt 6 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD 14 Pre CliniMACS | 27.1 | 21.4 | 10.58 | 8.15 | 3.63 | 18.3 | 19.6 | 18.9 | 12.6 | |

| CD14 Post CliniMACS (>90%) | 98.5 | 98.2 | 93.2 | 95.7 | 92.4 | 99.75 | 98.6 | 99.0 | 95.5 | |

| Viability postculture (Preinfusion) (>75%) |

80 | 92.3 | 96.8 | 93 | 97 | 91 | 91 | 85.8 | 88.1 | |

| DC-like morph | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| CD14 Pre-infusion (< 15%) | 6.28 | 4.81 | 0.51 | 6.63 | 7.93 | 13.3 | 37.4 | 11.07 | 1.72 | |

| Endotoxin level (< 5EU/kg) | NT | NT | NT | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.24 | |

| HLA-DR | 56.16 | 92.75 | 47.24 | 94.36 | 95.12 | 95.87 | 95.84 | 97.7 | 86.66 | |

| CD86 | 30.48 | 86.69 | 25.1 | 8 | 55.35 | 43.59 | 94.68 | 89.42 | 73.63 | 94.71 |

| CD80 | 4.01 | 13.61 | 2.03 | 3 | 2.36 | 41.56 | 21.84 | 3.15 | 56.14 | |

| CD83 | 65.37 | 92.53 | 2.29 | 66.94 | 3.93 | 47.77 | 56.55 | 1.81 | 51.5 |

NT – Not tested

Figures in bold represent the release criteria while non-bolded figures represent preferred criteria or measurement of DC phenotype.

In contrast to the proportion of CD14+ monocytes in the volunteer samples, the proportion of CD14+ monocytes in the apheresis product from the HCV patients was not only generally lower but also showed a greater variation, ranging from 3.63–19.6% (average 13.5%) (Table 3). Nevertheless, each preparation met the release criteria and was therefore compliant with the previously approved specification.

Previous studies [23] showed that the proportion of lipopeptide-loaded DC that expressed recognized markers of DC maturation viz. HLA DR, CD80, CD83, CD86, was usually ~90%. These studies were used as a yardstick for the clinical scale samples used in this trial (Table 3). Analysis of the compliant final products, showed that only a proportion achieved levels of the DC maturation markers similar to those in the preclinical trial, irrespective of whether the product was derived from a volunteer or patient. These results highlight difficulties in the translation of laboratory scale experiments into clinical scale. This was particularly relevant in the case of patient #6 who was scheduled to receive three doses of 5 × 107 cells by the IV route, but who only received three doses of 2 × 107 cells. To avoid simply duplicating the treatment of patient #5 (who received three doses of 2 × 107 cells IV and 1 × 107 cells ID), patient #6 was infused by the ID route only.

Clinical findings

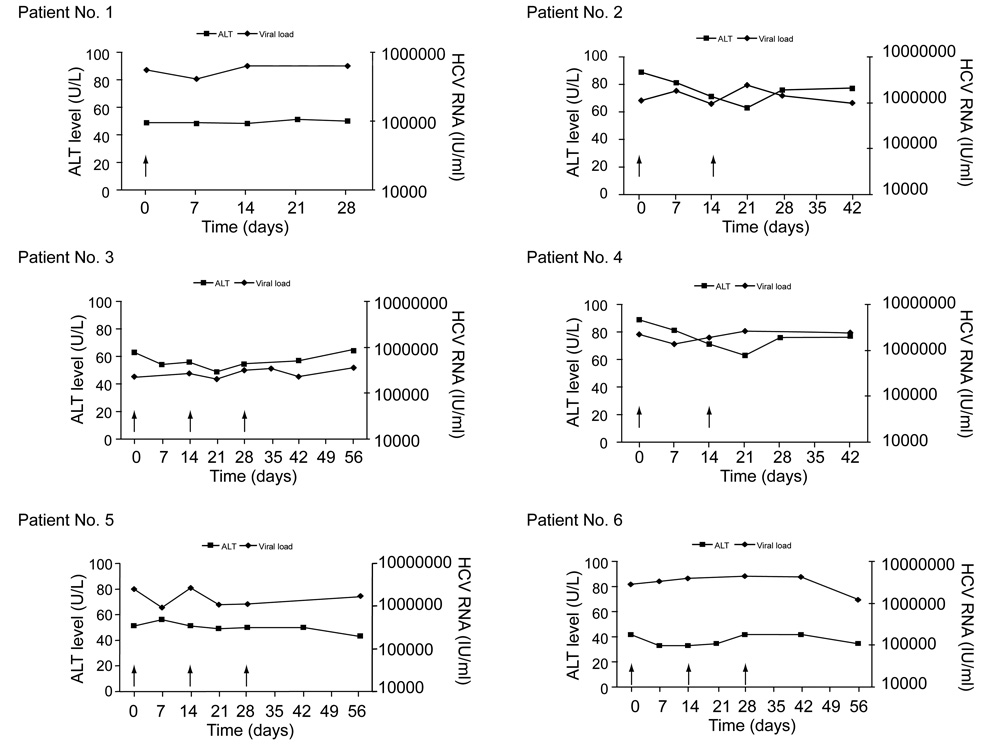

All patients tolerated the infusions well with no serious or grade 3 or 4 adverse events reported. The most common adverse events were injection site rash and erythema (n = 6), flu like symptoms (n = 5), headaches (n = 4), and increased fatigue (n = 4). There were no changes in vital signs or temperature apart from one patient who developed mild hypertension on a background of borderline hypertension. Laboratory parameters including liver function tests, urea, creatinine, full blood count, serum calcium, and phosphate levels were unchanged. There were no dose- or time-dependent decreases in the HCV viral load following the infusions (Fig. 1). The median viral load change from baseline 1 and 4 weeks after the last DC infusion was 0.08 log10 IU/ml and 0.05 log10 IU/ml respectively. Similarly, no significant effect was observed on serum ALT levels with the median change from baseline 1 and 4 weeks after the last infusion being −6.0 and −6.0 U/L respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Serum HCV RNA (diamonds) and ALT levels (squares) in individual patients during and after injections of autologous HCV lipopeptide-pulsed dendritic cells (arrows).

Analysis of interferon-γ responses in PBMC

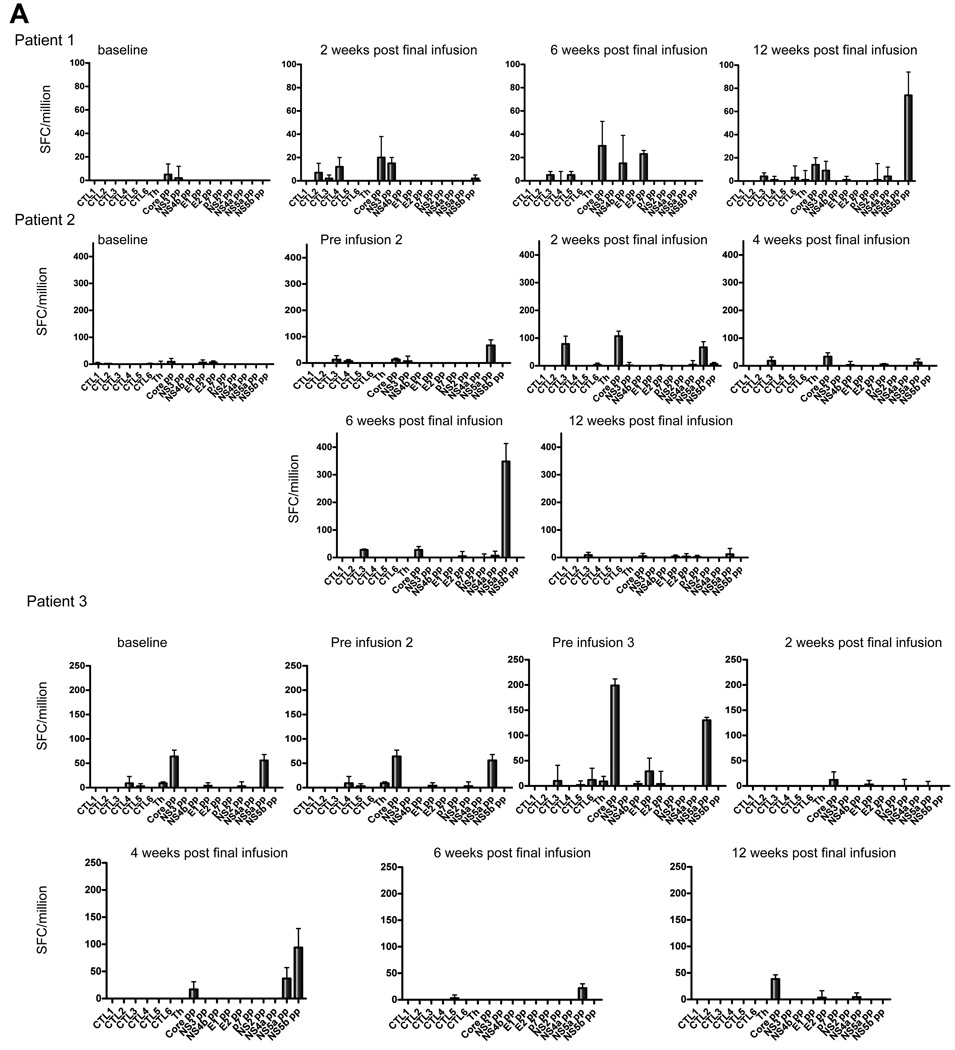

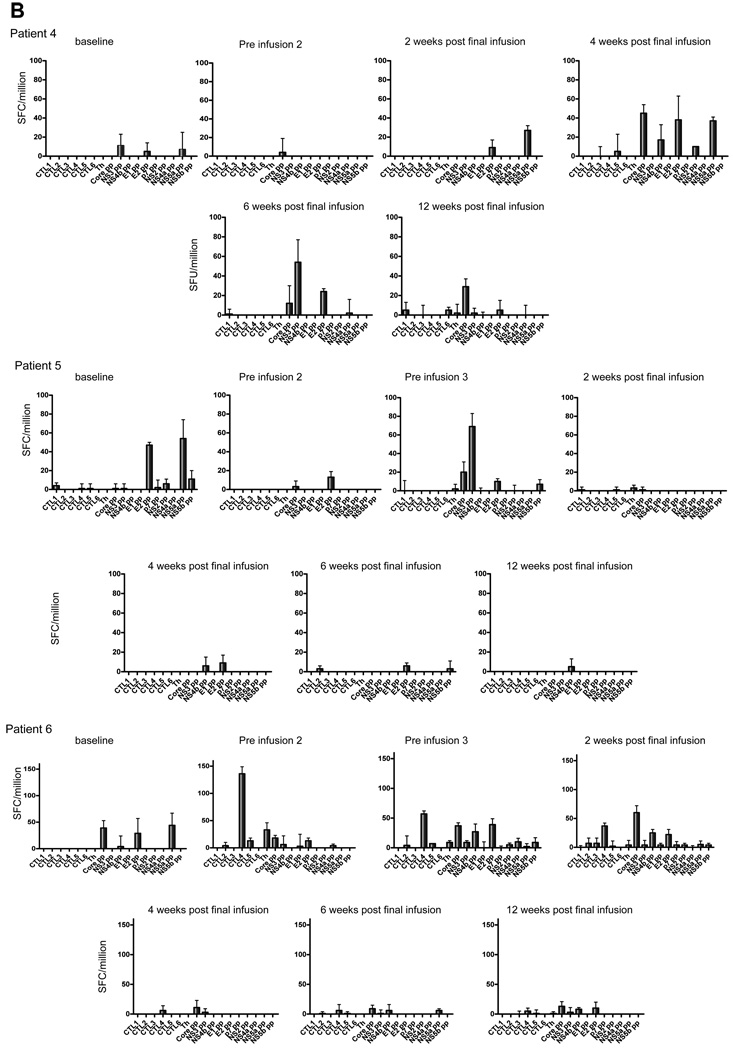

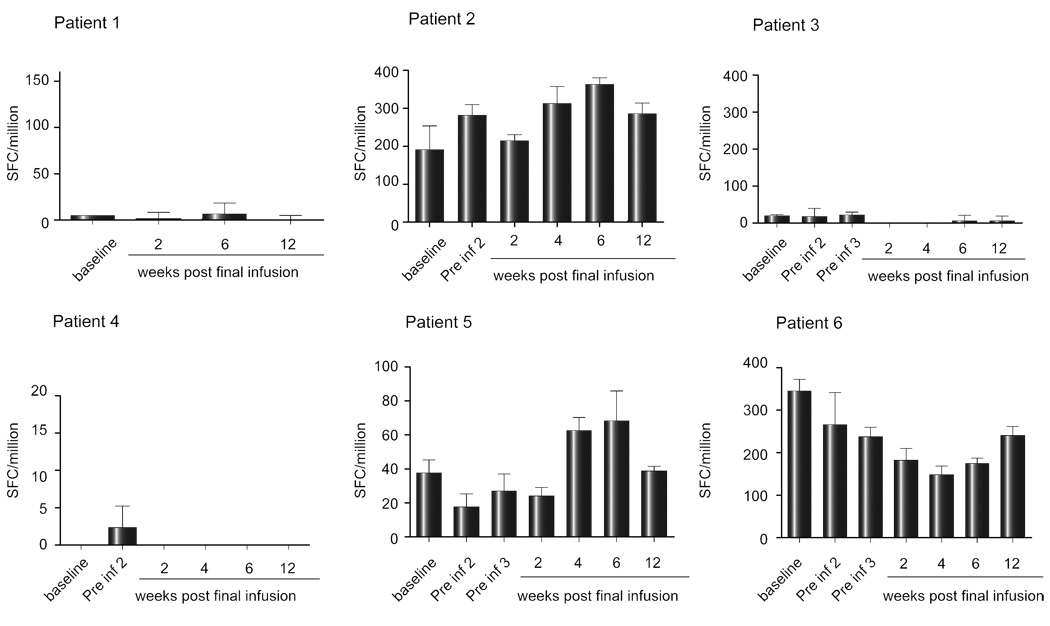

Cell mediated immunity was measured by ELIspot, as this is most sensitive and quantitative, and because the frequency of responses in this patient group may not be detectable with tetramer staining or intracellular cytokine staining measured by flow cytometry. IFN-γ ELIspot responses were examined in PBMC taken immediately prior to each DC infusion and in samples taken 2, 4, 6, and 12 weeks after the previous infusion. The baseline level of IFN-γ secreting cells prior to DC infusion was ~20 spot forming cells (SFC)/million PBMC. Each patient showed increased numbers of SFC, although the timing differed in different patients and the responses were transient (Fig. 2). Only three patients (#1, #2, and #6) showed a clear response to a peptide contained in the cellular vaccine that was generally mirrored by responsiveness to the peptide pools that encompassed individual CTL peptides. Each patient showed multispecific de novo responses that may be explained by epitope spreading, shown in Fig. 2 as the response to individual CTL peptides or peptide pools. To ensure that any changes in the level of the IFN-γ response to individual proteins were not due to fluctuations in the assay, the IFN-γ response of PBMC from each patient to an immunodominant influenza virus peptide was examined in parallel. Although there was some variation (Fig. 3), this was minimal compared with the changes in the HCV-specific responses.

Fig. 2. IFN-γ ELIspot results after HCV peptide stimulation for patients 1–6.

(A) Patients 1–3. (B) Patients 4–6. Blood samples were taken at fortnightly intervals over the course of the treatment up to 12 weeks post-final infusion. ELIspot to detect expression of IFN-γ were set up using PBMC isolated by ficoll density gradient separation and stimulated for 20–24h with individual peptides (core 132, core 35, core 177, NS3 1406, NS4B 1807, and NS4B 1851) representing the lipopeptides used in the DC immunotherapy, and 10 peptide pools spanning the entire HCV polyprotein. Bars representing spot forming cells/million cells. Negative control responses were subtracted from each, with error bars representing ± 1 standard deviation.

Fig. 3. IFN-γ ELIspot data for Influenza virus (flu) matrix peptide over the course of treatment for each patient.

Blood samples were taken at fortnightly intervals up to 12 weeks post-final infusion and IFN-γ ELIspots were set up and analysed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Note that the y-axes differ in different panels.

Laboratory analyses

To complement the ELIspot analyses, serum samples from each time point were examined for changes in the anti-core antibody titre and the levels of common cytokines, viz. IL2, IL4, IL6, IL8, IL10, IL12, IL13, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in the circulation. Despite the obvious (transient) increase in SFC detected by ELIspot, no significant differences were detected in any of the above parameters (results not shown).

Although the CTL peptide epitopes were chosen based on a high degree of conservation, it was not clear if any induced T cell responses would recognise epitopes expressed by the circulating virus. Accordingly, three regions of the viral genome viz. core, NS3, NS4B, were sequenced in the baseline or close to baseline serum sample from each patient. Although we were unable to amplify the NS4B region from three patients, RT-PCR amplification followed by sequencing of the product showed that only three epitopes differed from the sequence of the epitopes included in the cellular vaccine (Table 4). Of these mutations, the mutation in the core 132 epitope in patient #3 was located in an anchor residue (P2), suggesting that T cell responses to the epitope included in the vaccine would not recognise virus-infected cells. However, the other two mutations were not located in anchor residues. Consequently, the inability of the vaccine to reduce the viral load is probably not related to discordant sequences in the epitopes included in the vaccine and those in the circulating virus.

Table 4.

Summary of baseline viral RNA sequences.

| Patient # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL1, core 132 DLMGYIPLV |

No change | No change | DIMGYIPLV | No change | No change | No change |

| CTL2 core 35 YLLPRRGPRL |

No change | No change | No change | No change | No change | No change |

| CTL3 core 177 FLLALLSCLTV |

No change | No change | No change | No change | No change | No change |

| CTL4 NS3 1406 KLVALGINAV |

KLVALGVNAV* | No change | KLVALGVNAV | No change | No change | NP |

| CTL5 NS4B 1807 LLFNILGGWV |

NP** | NP | No change | No change | No change | NP |

| CTL6 NS4B 1851 ILAGYGAGV |

NP | NP | No change | No change | No change | NP |

Amino acids shown in bold represent mutations from the peptide epitope contained in the vaccine

NP-No product from RT-PC

Discussion

Although HCV may impair certain DC functions, we and others have argued in favour of DC immunotherapy for HCV infection, reasoning that DC, differentiated ex vivo, can act as efficient antigen presenting cells [10,26]. To support this, animals injected with HCV antigen-pulsed DC, elicited protective immunity against challenge with recombinant vaccinia viruses [27–29] or tumour cells expressing the homologous HCV protein [30]. Our studies showed that mice vaccinated with DC pulsed with a lipopeptide containing an influenza CD8+ T cell epitope killed peptide-pulsed target cells equally efficiently as mice previously infected with influenza [22].

In preparation for this trial, we immunized mice with DC pulsed with the HCV lipopeptides and showed no evidence of toxicity as a result, even when a large dose multiple was administered [22]. We chose to use lipopeptides which contain the peptide epitope linked to the lipid moiety, Pam2Cys, that induce DC maturation without additional maturation stimuli [31]. We also previously established a robust clinical-grade protocol to generate mature, human MoDC in SFM [23] as regulatory authorities discourage the use of bovine serum, and because human serum contains unpredictable levels of cytokines which may influence DC function and the outcome of any trial. That study [23] also showed that the addition of PGE2 to the culture increased the migration ability of the mature MoDC towards CCL21, the cognate receptor for CCR7 expressed in lymph nodes and demonstrated that the mature lipopeptide loaded MoDC were able to stimulate memory T cells. Thus, the trial was designed as a Phase 1 trial to demonstrate product safety with the added objectives of showing an increase in HCV-specific CD8+ T cell immunity and a reduction in the HCV viral load. To this end, the trial was successful as the first two objectives were achieved.

The trial was based on the previous demonstration that sustained viral responders to IFN-based therapy seldom show increased levels of ALT and on the finding that the HCV viral load is often reduced by several logs in acute phase patients, co-incident with a T cell response without a concomitant increase in ALT [1,2]. Thus, HCV clearance was likely to be non-cytolytic. Nevertheless, the potential to induce hepatitis was a major reason why the study was assessed by the Australian TGA and why patients were closely monitored after the DC infusion.

The results highlighted the wide variation in the proportion of CD14+ monocytes from different individuals and prevented the dose escalation as designed. Nevertheless, despite the large differences in CD14+ monocyte numbers, sufficient lipopeptide-loaded DC were generated in all but one patient, who co-incidentally had been planned to be infused with the highest total number of DC. Since patient #6, who only received the DC injections by the ID route, developed an ELIspot response to a greater number of peptides than patients who received IV and ID infusions, it is possible that DC delivered by the ID route may be more effective. However, the optimal route of delivery is still unclear [32] and previous studies demonstrated clinical efficacy after IV delivery [33]. When the trial was planned, there were no clear guidelines on the optimal route and consequently, we chose to deliver the DC by the IV route to target lymph nodes by the systemic circulation and by the ID route to target the lymphatic system.

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to use DC immunotherapy in HCV-infected patients. The group which failed conventional IFN-based therapy has few options for alternative therapy. We based the DC dose on previous clinical trials to treat tumours [34] although there is no recognised optimum dose. Although each patient generated de novo responses as determined by ELIspot, there was no apparent correlation with DC dose. However, responses to peptides not contained in the cellular vaccine were detected, suggesting that this was due to killing of HCV-infected hepatocytes, followed by phagocytosis and cross presentation of HCV antigens by liver-resident DC that we interpret to represent epitope spreading. The lack of any increase in the ALT level suggests that only a small number of hepatocytes were affected in this manner. Alternatively, locally produced cytokines may have stimulated IFNγ secretion by existing CD8+ T or CD4+ T cells, specific for immunodominant epitopes, for example on the NS5A and B proteins, transiently reversing the dysfunctional nature of these cells. It is also possible that these cells were present in undetectable numbers prior to the DC therapy or that they were previously restricted to the hepatic compartment. It would be of interest to determine the mechanism of this phenomenon and identify the epitopes recognized on these proteins that may represent useful future immunogens. The suggestion of epitope spreading was also made in a recent study after therapy with a yeast-based immunotherapy regimen [35].

Other therapeutic vaccine studies [36–39] to treat HCV-infected patients, who failed conventional IFN-based therapy, reported only a transient reduction in the viral load in three patients [36], despite the fact that three studies [37–39], designed to elicit cell mediated immunity, achieved this objective. Collectively these studies highlight the difficulty in breaking the immune tolerance associated with persistent HCV infection. The vaccines comprising T cell epitopes in adjuvant [38,39] are most similar to the lipopeptide-pulsed DC used in our trial. Our study was designed to examine proof of principle to determine if MoDC therapy could influence the course of the infection. In view of the possibility that an immune-based component may be necessary to augment antiviral therapy [40] we considered that MoDC therapy might fulfill this role, but for the moment, we believe that this is best served by interferon/ribavirin supplementation.

In principle, DC therapy is more likely to succeed in eliminating HCV infection in the liver, which can be infiltrated readily by effector T cells, than eliminating solid tumours which can be refractile to T cell infiltration. Thus, it is useful to examine reasons why the DC therapy was not more successful in the HCV patients. First, we believe that future DC therapy would benefit if the cells were infused by the ID route. Other studies support this interpretation [41]. Second, the lipopeptides represent conserved CTL epitopes that may differ to the sequence of the protein encoded by the infecting virus. Third, more than six epitopes may be required to eliminate the infection. Fourth, additional doses of DC may be necessary [41]. Similar studies to deliver whole viral antigens to DC would not only result in presentation of a greater number of CD8+ and CD4+ T cell epitopes, but also remove the requirement to tailor peptides to a particular HLA haplotype. Further studies of DC immunotherapy of HCV-infected patients that incorporate these points may be warranted.

Acknowledgements

We thank the nursing staff in the Liver Clinic, Alfred Hospital and the Alfred Centre, the Quality Control Officers of the ARCBS and Drs David Ritchie, David Woollard, and Bruce Loveland for helpful discussion and advice. We are greatly indebted to Paula Stoddard (MiltenyiBiotec) who freely gave time and expertise to ensure a successful outcome.

This study was supported by grant number RO1 A1054459 from the National Institutes of Health, USA and by donations from Perpetual Finance Pty, Sydney, Australia. MiltenyiBiotec supplied the CliniMACS instrument for the duration of the study.

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- DC

dendritic cells

- IFN

interferon

- LN

lymph nodes

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- SFC

spot forming cells

- MoDC

monocyte derived dendritic cells

- IDU

intravenous drug user

- ULN

upper limit of normal

- ID

intradermal

- IV

intravenous

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Bowen D, Walker C. Adaptive immune responses in acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2005;436:946–952. doi: 10.1038/nature04079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thimme R, Oldach D, Chang KM, Steiger C, Ray SC, Chisari FV. Determinants of viral clearance and persistence during acute hepatitis C virus infections. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1395–1406. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villano SA, Vlahov D, Nelson KE, Cohn S, Thomas DL. Persistence of viremia and the importance of long-term follow up after acute hepatitis C infection. Hepatol. 1999;29:908–914. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gale M, Foy E. Evasion of intracellular host defence by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;436:939–945. doi: 10.1038/nature04078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato N, Ootsuyama Y, Sekiya H, Ohkoshi S, Nakazawa T, Hijikata M, Shimotohno K. Genetic drift in hypervariable region 1 of the viral genome in persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 1994;68:4776–4784. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4776-4784.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson AL, Kimura Y, Igarashi S, Eichelberger J, Houghton M, Sidney J, et al. The outcome of hepatitis C virus infection is predicted by escapte mutations in epitopes targeted by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 2001;15:883–895. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crotta S, Stilla A, Wack A, D’Andrea A, Nuti S, D’Oro U, et al. Inhibition of natural killer cells through engagement of the CD81 by the major hepatitis C virus envelope protein. J Exp Med. 2002;195:35–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng CT, Klimpel GR. Binding of the hepatitis C virus E2 to CD81 inhibits natural killer cell function. J Exp Med. 2002;195:43–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wedemeyer H, He XS, Nascimbeni M, Davis AR, Greenberg HB, Hoofnagle JH, et al. Impaired effector function of hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cell in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:3447–3458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gowans EJ, Jones KL, Bharadwaj M, Jackson DC. Prospects for dendritic cell vaccination in persistent infection with hepatitis C virus. J Clin Virol. 2004;30:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radziewicz H, Ibegbu CC, Fernandez ML, Workowski KA, Obideen K, Wehbi M, et al. Liver-infiltrating lymphocytes in chronic human hepatitis C virus infection display an exhausted phenotype with high levels of PD-1 and low levels of CD127 expression. J Virol. 2007;81:2545–2553. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02021-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Jones KL, Woollard DJ, Dromey J, Paukovics G, Plebanski M, Gowans EJ. Defining target antigens for CD25+FOXP3+IFN-γ− regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:197–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donaldson PT. The interrelationship between hepatitis C and HLA. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:280–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urbani S, Boni C, Missale G, Elia G, Cavallo C, Massari M, et al. Virus-specific CD8+ lymphocytes share the same effector-memory phenotype but exhibit junctional differences in acute hepatitis B and C. J Virol. 2002;76:12423–12434. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12423-12434.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbani S, Amadei B, Fisicaro P, Tola D, Orlandini A, Sacchelli L, et al. Outcome of acute hepatitis C is related to virus-specific CD4 function and maturation of antiviral memory CD8 responses. Hepatology. 2006 Jul;44(1):126–139. doi: 10.1002/hep.21242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randolph GJ, Beaulieu S, Lebecque S, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science. 1998;282:480–483. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Longman RS, Talal AH, Jacobson IM, Rice CM, Albert ML. Normal functional capacity in circulating myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Inf Dis. 2005;192:497–503. doi: 10.1086/431523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccioli D, Tavarini S, Nuti S, Colombatto P, Brunetto, Bonino F, et al. Comparable functions of plasmacytoid and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in chronic hepatitis C patients and healthy donors. J Hepatol. 2005;42:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longman RS, Talal AH, Jacobson IM, Albert ML, Rice CM. Presence of functional dendritic cells in patients chronically infected with hepatitis C. Blood. 2004;103:1026–1029. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chua BY, Healy A, Cameron P, Fowler NL, Brown LE, Zeng W, et al. Maturation of dendritic cells with lipopeptides that represent vaccine candidates for hepatitis C virus. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:67–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson DC, Deliyannis G, Eriksson E, Dinatale I, Rizkalla M, Gowans EJ. Dendritic cell immunotherapy of hepatitis C virus infection: toxicology of lipopeptide-loaded dendritic cells. Int J Peptide Res Ther. 2005;11:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones KL, Brown LE, Eriksson EMY, Ffrench RA, Latour PA, Loveland BE, et al. Human dendritic cells pulsed with specific lipopeptides stimulate autologous antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells without the addition of exogenous maturation factors. J Viral Hepatitis. 2008;15:761–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng W, Ghosh S, Lau YF, Brown LE, Jackson DC. Highly immunogenic and totally synthetic lipopeptides as self-adjuvanting immunocontraceptive vaccines. J Immunol. 2002;169:4905–4912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trowbridge R, Sloots TP, Buda P, Faoagali J, Hyland C, Young I, Gowans EJ. An ELISA for the detection of antibody to the core antigen of hepatitis C virus: use in diagnosis and analysis of indeterminate samples. J.Hepatol. 1996;24:532–538. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson M, Babcock E, Grakoui A, Shoukry N, Lauer G, Rice C, et al. Lack of phenotypic and functional impairment in dendritic cells from chimpanzees chronically infected with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2004;78:6151–6161. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6151-6161.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Racanelli V, Behrens SE, Aliberti J, Rehermann B. Dendritic cells transfected with cytopathic self-replicating RNA induce crosspriming of CD8+ T cells and antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2004;20:47–58. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu H, Huang H, Xiang J, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. Dendritic cells pulsed with hepatitis C virus NS3 protein induce immune responses and protection from infection with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing NS3. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1–10. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81423-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuzushita N, Gregory SH, Monti NA, Carlson R, Gehring S, Wands JR. Vaccination with protein-transduced dendritic cells elicits a sustained response to hepatitis C viral antigens. Gastroenterol. 2006;130:453–464. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Encke J, Findeklee J, Geib J, Pfaff E, Stremmel W. Prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination with dendritic cells against hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;142:362–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown LE, Jackson DC. Lipid-based self-adjuvanting vaccines. Curr Drug Delivery. 2005;2:383–393. doi: 10.2174/156720105774370258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prince HM, Wall DM, Ritchie D, Honemann D, Harrison S, Quach H, et al. In vivo tracking of dendritic cells in patients with multiple myeloma. J Immunother. 2008;31:166–179. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31815c5153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tjoa BA, Simmons SJ, Bowes VA, Ragde H, Rogers M, Elgamal A, et al. Evaluation of phaseI/II clinical trials in prostate cancer with dendritic cells and PSMA peptides. Prostate. 1998;36:39–44. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980615)36:1<39::aid-pros6>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smithers M, O’Connell K, MacFadyen S, Chambers M, Greenwood K, Boyce A, et al. Clinical response after intradermal immature dendritic cell vaccination in metastatic melanoma is associated with immune response to particulate antigen. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0318-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiff ER, Everson GT, Tsai N, Bzowej NH, Gish RG, McHutchison JG, et al. HCV-specific cellular immunity, RNA reductions, and normalization of ALT in chronic HCV subjects after treatment with GI-5005, a yeast-based immunotherapy targeting NS3 and core: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled Phase 1B study. Hepatology. 2007;44 Abs #LB17. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nevens F, Roskams T, Van Vlierberghe H, Horsmans Y, Sprengers D, Elewaut A, et al. A pilot study of therapeutic vaccination with envelope protein E1 in 35 patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol. 2003;38:1289–1296. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alvarez-Lajonchere L, Shoukry NH, Gra B, Amador-Canizares Y, Helle F, Bedard N, et al. Immunogenicity of CIGB-230, a therapeutic DNA vaccine preparation, in HCV-chronically infected individuals in a Phase I clinical trial. J Viral Hep. 2009;16:156–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klade CS, Wedemeyer H, Berg T, Hinrichsen H, Cholewinska G, Zeuzem S, et al. Therapeutic vaccination of chronic hepatitis C nonresponder patients with the peptide vaccine IC41. Gastroenterol. 2008;134:1385–1395. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yutani S, Yamada A, Yoshida K, Takao Y, Tamura M, Komatsu N, et al. Phase 1 clinical study of a personalized peptide vaccination for patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) 1b who failed to respond to interferon-based therapy. Vaccine. 2007;25:7429–7435. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawitz E, Rodriguez-Torres M, Muir AJ, Kieffer TL, McNair L, Khunvichai A, McHutchison JG. Antiviral effects and safety of telaprevir, peginterferon alfa-2a, and ribavirin for 28 days in hepatitis C patients. J Hepatol. 2008;49:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vulink A, Radford K, Melief C, Hart D. Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;99:363–407. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(07)99006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]