Abstract

Calcifying biologic nanoparticles (NPs) develop under cell culture conditions from homogenates of diverse tissue samples displaying extraosseous mineralization, including kidney stones and calcified aneurysms. Probes to definitively identify NPs in biologic systems are lacking. Therefore, the aim of this study was to begin to establish a proteomic biosignature of NPs in order to facilitate more definitive investigation of their contribution to disease. Biologic NPs derived from human kidney stones and calcified aneurysms were completely decalcified by overnight treatment with EDTA or brief incubation in HCl, as evidenced by lack of a calcium shell and of Alizarin Red S staining, by transmission electron microscopy and confocal microscopy, respectively. Decalcified NPs contained numerous proteins including some from bovine serum and others of prokaryotic origin. Most prominent of the latter group was EF-Tu, which appeared identical to EF-Tu from S. epidermidis. A monoclonal antibody against human EF-Tu recognized a protein in Western blots of total NP lysate, as well as in intact NPs by immunofluorescence and immunogold EM. Approximately 8% of NPs were quantitatively recognized by the antibody by flow cytometry. Therefore, we have defined methods to reproducibly decalcify biologic NPs, and identified key components of their proteome. These elements, including EF-Tu, can be used as biomarkers to further define processes which mediate propagation of biologic NPs and their contribution to disease.

Keywords: Elongation factor Tu, calcification, FACS, nanoparticles, nephrolithiasis, proteomics

INTRODUCTION

Calcifying biologic nanoparticles (NPs) have been identified from diverse tissue samples including kidney stones and calcified aneurysms (1). Whether or not they represent independent, biologic entities or a form of self-perpetuating biomineralization remains controversial (2–4). Given the evidence that diverse forms of NPs have biological affects, both possibilities are of interest because of their potential contribution to pathophysiological processes (5).

Biochemical and spectral analysis shows that some NPs are composed of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and nucleic acids. (2–4, 6–8). However, whether NPs contain a unique collection of biomolecules, and whether they possess specific biomolecular and biologic activity, is unknown. Probes to definitively identify NPs in biologic systems are lacking. Therefore, the aim of this study was to take steps to establish a proteomic biosignature of NPs in order to facilitate more definitive investigations of their contribution in disease.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

All protocols were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

NP isolation and propagation

All water used for experiments was double-distilled. Both water and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) used to wash isolated NPs were 0.2 μm-filtered before use. To separate NPs from solution they were centrifuged at 60,000g for 1 hour at 4°C followed by pellet re-suspension. For propagation, NPs were placed in standard culture medium [(Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% γ–irradiated fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA)], and maintained in a tissue culture incubator (37°C, 13%_CO2). NPs were prepared from calcified aneurysms (including strain A2), as previously described (1). NPs were also prepared from calcium phosphate kidney stones (strains HA399 and AP11) after compositional analysis by infrared spectroscopy performed in the Mayo Clinic Metals laboratory. Human stones were washed with distilled nanopure water, dried, pulverized using a mortar and pestle, and stored at 4°C in plastic vials. To extract NPs, pulverized stones were demineralized using 1N HCl for 10 minutes with constant stirring, neutralized with 1N NaOH, and centrifuged. The pellet was suspended in DMEM, filtered through a Whatman No. 42 filter, sterile-filtered through a 0.2 μm Millipore filter, inoculated into 250 ml vented tissue culture flasks (Corning; Corning, NY) containing 70 ml of standard culture medium and placed in incubation. NP replication was assessed qualitatively using light microscopy (Olympus BX41 microscope equipped with a CytoViva dark-field adapter and 100× UPlanFLN oil lens; CytoViva, Inc., Auburn, AL) and quantitatively by turbidimetry in Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) (Model 2100N Turbidometer Hach Co., Loveland, CO). Every 2–4 wks flasks containing adherent calcific NP biofilm were scraped with a rubber spatula, diluted 1:10 into fresh standard culture medium, and subcultured. Representative flasks were screened for Mycoplasma contamination using a sensitive rapid PCR test performed in the Mayo Clinic Microbiology Laboratory, and were always negative.

Flasks were scraped after 30 days incubation to harvest calcified NPs for experiments, and the resulting NPs (free-floating combined with those released by the scraping) were pelleted as described above. Where indicated, NPs in the resulting pellet were decalcified by incubation of the pellet in: 1) 0.5M EDTA, 4°C for 16 hrs; PBS, pH 4, 4°C for 16 hours; or 0.5N HCl for 5 minutes. In other experiments performed to define conditions that might favor propagation of NPs lacking a calcium shell, NPs were seeded into medium adjusted to low calcium (0.18 mM) and varied pH (7.5, 6.5, or 5.5). After 4 weeks the presence of free and biofilm-adherent NPs was semi-quantitatively scored (0–3+) under light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). For quantitative assessment of NP mass adherent NPs were also scraped free from the flask bottom into the medium and collected together with the free-floating (planktonic) NPs. The turbidity of the medium was then measured.

For harvest the solution containing decalcified NPs was centrifuged and the resulting pellet was twice re-suspended in PBS (pH 7) and centrifuged to wash the NPs, since calcium phosphate will not readily dissolve in this solution. The final pellet containing rinsed, decalcified NPs was suspended in PBS or other solution described below for specific protocols.

Alizarin Red S Staining

Isolated rinsed calcified and decalcified NPs were incubated in PBS containing 0.1% Alizarin Red S for 15 minutes. These stained NPs were then rinsed three times by centrifugation, with each resulting pellet being re-suspended in fresh PBS, then examined using the dark-field imaging system described above, equipped with a dual-fluorescence module and a halogen light source. The excitation light was filtered through a 560nm-40× filter, and emitted light was passed through a 580nm long-pass filter.

Electron Microscopy

For SEM washed calcified or decalcified pellets, prepared as above, were critical-point dried, layered with gold, and examined with a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Hitachi S4700, Japan). For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), washed calcified or decalcified NPs were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4°C, coated onto a copper grid, cut and embedded in epoxy resin, and examined with a transmission electron microscope (FEI Tecnai 12, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA). Elemental analysis of NPs was performed at the time of TEM using an EDAX pulse processor system [Energy Dispersion Spectroscopy (EDS), Inc. Mahwah New Jersey USA].

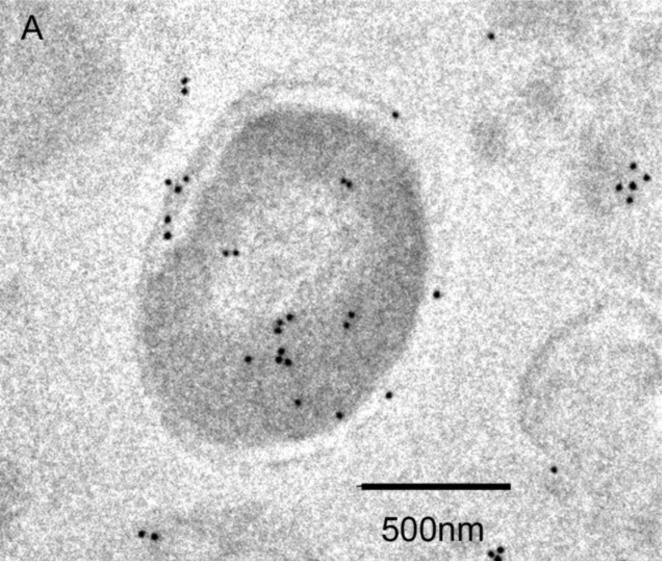

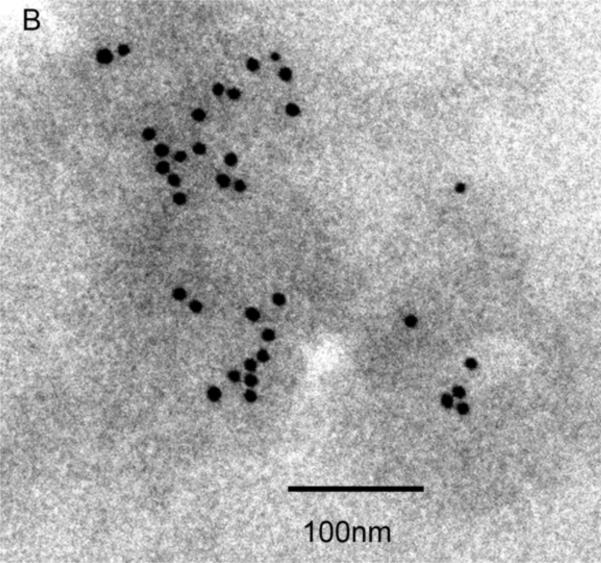

For immunogold labeling, decalcified NPs (AP-11 strain) were incubated in Trump's fixative overnight at 4°C, then ultra-thin sections were cut and placed on 200 mesh nickel grids. The grids were treated with 1% glycine in filtered water for 15 minutes at room temperature, and then incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against EF-Tu (1:10) in PBS plus Tween-Natural Goat serum (PBST-NGS) for 1hr at room temperature. The grids were thoroughly washed in rinsing buffer (PBST-NGS) followed by incubation with a gold-labeled secondary antibody (1:20) for 1hr at room temperature. Grids were washed with rinsing buffer (PBST-NGS) followed by water, then air-dried before examination under TEM as described above.

Proteomic studies

A pellet of decalcified NPs, prepared as described above, was suspended in PBS containing 1mM Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). The solution was sonicated for 20 minutes on ice (10% wave intensity), then centrifuged at 8,000g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Proteins in the supernatant were resolved via SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (50 mM DTT) using a 4–15% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To identify bands of interest gels were stained with 0.1% Coomasie blue R250 in 50% methanol and 10% acetic acid, then de-stained with 15% methanol and 10% acetic acid.

Major protein bands were excised for digestion and identification by tandem Mass Spectroscopy in the Mayo Clinic Proteomics core facility. For Western blots, gels were electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane (Biorad) and probed using commercial antibodies against human EF-Tu (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA.)

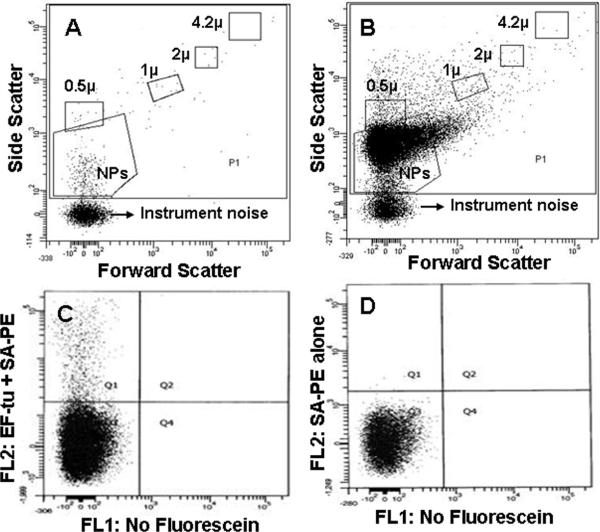

Flow cytometric analysis of biological NPs

All reagents were double-filtered through 0.2μm membrane filters. Decalcified NPs were re-suspended in Hanks'/HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 and sonicated (10% wave intensity) or vortexed for 5 minutes. NP suspensions (100 μl) were incubated with biotinylated mouse monoclonal anti-human EF-Tu antibody (5 μl) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature in the dark with Phycoerythrin- conjugated Streptavidin (5μl, Streptavidin- PE). NP suspensions were diluted to 500 μl with Hanks/HEPES buffer, vortexed for 30 seconds and then analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCanto™, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Non-specific binding of Streptavidin-PE on NPs was verified by incubation with Streptavidin-PE alone without biotinylated EF-Tu antibody.

RESULTS

Structural characterization of biologic NPs

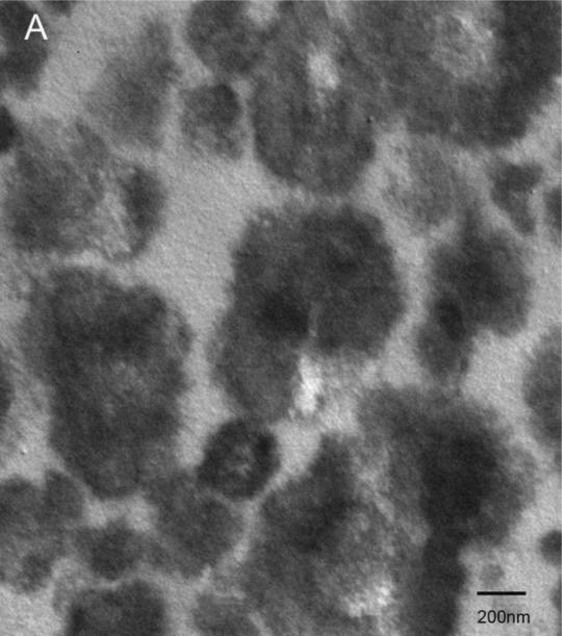

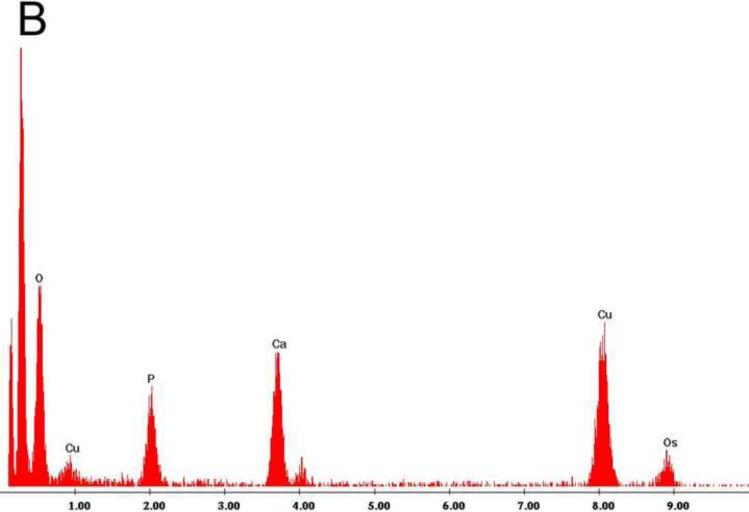

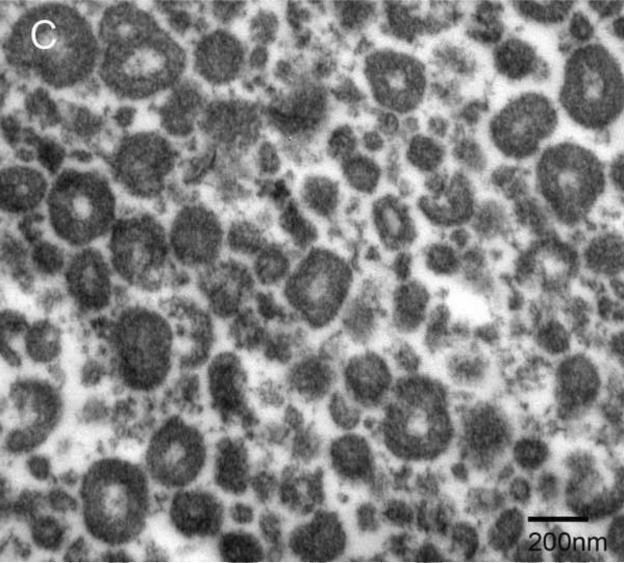

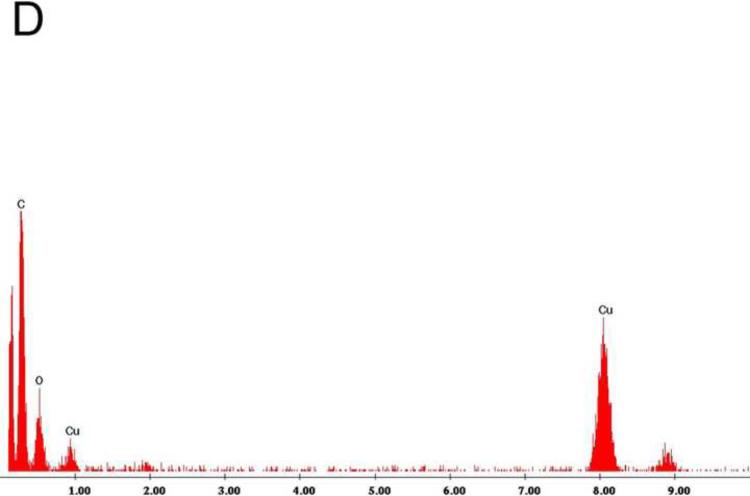

Examination under TEM revealed that NPs had an electron-dense shell (Figure 1A) that was comprised of calcium phosphate by EDS analysis (Figure 1B). After decalcification with 0.5M EDTA, an electron-dense 100–200 nm inner core lacking calcium and phosphate remained (Figure 1C, D). Calcified NPs were visible by dark-field microscopy at 100× magnification (Figure 2A), but appeared smaller after decalcification with 0.5M EDTA (Figure 2B). When stained with Alizarin Red S, calcified NPs showed bright red fluorescence (Figure 2C). Conversely, Alizarin Red S did not stain EDTA-decalcified NPs (Figure 2D). Treatment with 0.5N HCl for 5 min also eliminated Alizarin Red S staining (not shown). Alizarin Red S staining was reduced but not absent in NPs treated for 16hrs with PBS at pH 4.

Figure 1. Transmission electron micrographs of biologic NPs derived from a human kidney stone.

Prior to demineralization (A) NPs contained a thick calcium phosphate shell as confirmed by energy dispersion spectroscopy (EDS, Panel B). After EDTA decalcification with EDTA an electron dense core remained (Panel C) that lacked calcium by EDS (Panel D).

Figure 2. Light micrographs of biologic NPs derived from a human kidney stone.

NPs are shown before (Panels A, B) and after (Panels C, D) decalcification with 0.5M EDTA, using transmitted light (Panels A, C) before and after application of Alizarin Red S under 560 nm laser excitation (Panels B, D). Alizarin Red S staining was abolished by EDTA treatment (Panel D).

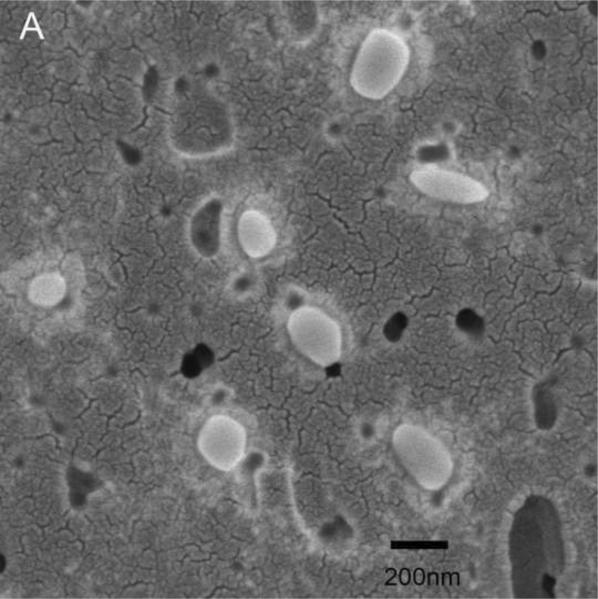

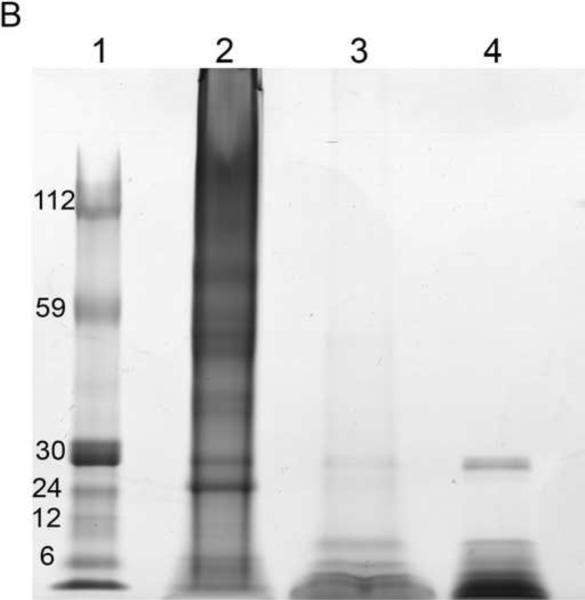

EDTA-decalcified NPs trapped on 0.2 μm filter paper and visualized under SEM were smooth spheres 100–200 nm in size (Figure 3A). These EDTA-decalcified NPs contained numerous proteins when they were lysed and resolved by SDS-PAGE (Figure 3B). Treatment of the EDTA-decalcified NPs with Proteinase K abolished the protein bands (Figure 3B), and the 100–200 nm structures were no longer observed (not shown).

Figure 3. Decalcified biologic NPs.

Panel A: 100–200 nm spheres were observed under SEM. Panel B: Lysate of these decalcified NPs contained numerous proteins when resolved by SDS-PAGE; after treatment with Proteinase K only a band corresponding to Protease K itself remained. Lane 1: Molecular weight markers; Lane 2: EDTA- decalcified NP lysate; Lane 3: EDTA- decalcified NP lysates treated with Proteinase K; Lane 4: Proteinase K.

Conditions were also tested that were designed to propagate biologic NPs that lacked a calcium shell. Since calcium phosphate crystallization is dependent upon the calcium × phosphate ion product, as well as pH, the calcium concentration (and thus the ion product) was maximally reduced to 0.18mM by using calcium-free medium together with 10% serum, and combined with 3 pH conditions that roughly cover the physiologic range (5.5, 6.5 and 7.5). The number and size of NPs which developed after 4 weeks in culture was dramatically reduced by the low calcium, pH 7.5 medium, compared to controls (3.6 mM calcium, pH 7.5). Reduction of pH of the low calcium medium to 5.5 further reduced biofilm NP growth, and essentially abolished growth of planktonic NPs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Growth of NPs in conditions of low pH, low calcium.

| NPs | 3.6 mM Ca2+ |

0.18 mM Ca2+ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.5 | pH 7.5 | pH 6.5 | pH 5.5 | ||

| Biofilm | Microscopy | +++ | + | + | − |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 2660 | 47 | 27 | 18 | |

| Planktonic | Microscopy | +++ | + | − | − |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 190 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

NP growth of control samples after 4 weeks in culture, determined visually by light microscopy and SEM.

attenuated growth.

sparse or no growth. Turbidometric measurements were performed in corresponding samples.

Proteomic analysis of NPs

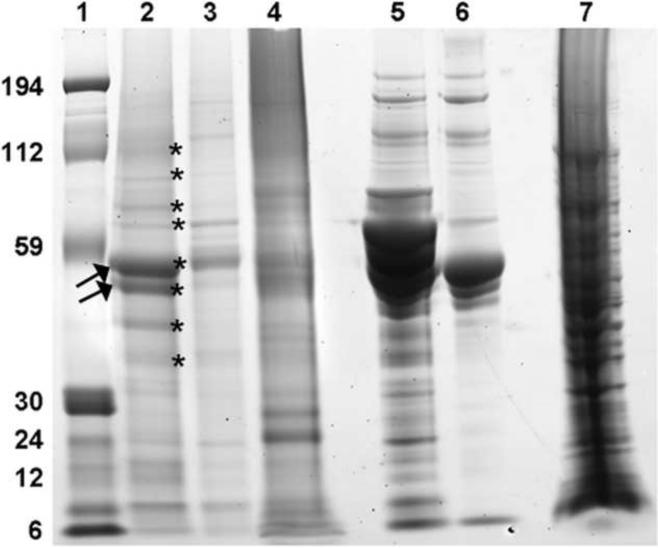

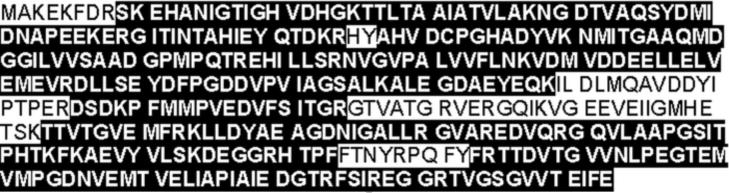

In order to identify the major proteins that appeared to make up the core of biologic NPs, the eight most prominent bands were cut from an SDS-PAGE gel obtained from decalcified HA 399 NPs (Figure 4), trypsin-digested, and analyzed by MS/MS in the Mayo Clinic Proteomics Core. Several conserved bacterial proteins were identified including elongation factors (EF-Tu, EF- G), Fructose binding aldolase and Chaperone C1pB (Table 2). Importantly, homologies were strong to prokaryotic forms of these proteins and not to human or bovine. However, in addition to these microbial proteins, others were detected that possibly arose from bovine serum, including Bovine Fetuin A, Bovine Fetuin B and Fetal Bovine Hemoglobin (Table 2). The MS/MS analysis for EF-Tu was repeated after chymotrypsin digestion in order to obtain more complete sequence. The majority of the protein (83.5%; 359/394 amino acids) was sequenced between the 2 digestions, with complete homology of this extensive sequence to EF-Tu from Staphylococcus epidermidis (Figure 5). A band of the correct size for EF-Tu was detected when total lysates from decalcified NPs (HA399, A2 and AP-11 strains) and E. coli were probed with a commercial antibody against human EF-Tu (not shown). However, it was absent in fetal bovine serum and hydroxyapatite crystals pre-incubated in fetal bovine serum overnight.

Figure 4. Proteomic profile of decalcified biologic NPs.

NP lysates obtained from two strains of hydroxyapatite kidney stones (HA399, lane 2) and AP11 (lane 3) and from calcified aortic aneurysm (A2, lane 4) were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Also shown for comparison are fetal bovine serum (FBS, lane 5), synthetic hydroxyapatite crystals (HA) pre-incubated with serum (lane 6) and E. coli lysate (lane 7). Bands indicated by stars in the human kidney stone NP lysate (HA 399) in lane 2 were cut and subjected to trypsin digestion and mass spectroscopy. The most prominent bands (arrow) were identified as EF-Tu. Lane 1: Molecular weight markers.

Table 2.

NP proteins identified by MS/MS of prominent bands in Figure 4.

| Band | Band apparent MW (Da) | Protein identity | MW of intact protein (Da) | Source | % coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 112,000 | Chaperone clpB | 98,357 | Staphylococcus aureus | 2 |

| Elongation factor G (EF-G) | 77009 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 26 | ||

| Translation initiation factor IF-2 | 79,352 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 6 | ||

| Elongation factor G (EF-G) | 76,849 | Staphylococcus aureus | 27 | ||

| 2 | 100,000 | Elongation factor tu (EF-Tu) | 43,188 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 6 |

| Hemoglobin beta chain | 15,963 | Bovine | 79 | ||

| Hemoglobin alpha chain | 15,157 | Bovine | 32 | ||

| Ribosomal protein L14 | 13,256 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 31 | ||

| Ribosomal protein S10 | 11,569 | Staphylococcus aureus | 22 | ||

| 3 | 80,000 | HTH-type transcriptional regulator sarZ | 17,537 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 14 |

| Arginine repressor | 17,288 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 32 | ||

| Hemoglobin beta chain | 15,963 | Bovine | 36 | ||

| 4 | 70,000 | Elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) | 43,188 | Staphylococcus aureus | 20 |

| Ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase | 35,528 | 11 | |||

| UPF0365 protein SERP1140 | 35,152 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 58 | ||

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 32,948 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 42 | ||

| Carbamate kinase 2 | 33,194 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | |||

| 5 | 55,000 | Elongation factor tu (EF-Tu) | 43,188 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 84 |

| Enolase | 47,163 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 25 | ||

| 6 | 50,000 | Chaperone clpB | 98,241 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 13 |

| Fetuin A | 39,193 | Bovine | 9 | ||

| Elongation factor tu (EF-Tu) | 43,134 | Staphylococcus aureus | 5 | ||

| 7 | 40,000 | Fetuin A | 39,193 | Bovine | 56 |

| Putative aldehyde dehydrogenase | 54,271 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 32 | ||

| GMP synthase | 58,420 | Staphylococcus | 21 | ||

| Malate dehydrogenase | 56,356 | Staphylococcus | 53 | ||

| 8 | 35,000 | Fetuin A | 39,193 | Bovine | 7 |

| Hemoglobin beta chain | 15,963 | Bovine | 16 |

Figure 5. Amino acid sequence of EF-Tu from S. epidermidis.

Fragments covering 83.5% of the total protein (portions highlighted in black) were identified in the NP lysate after trypsin or chymotrypsin digestion.

Electron microscopy

To determine the localization of EF-Tu within decalcified NPs they were exposed to a primary antibody directed against EF-Tu, followed by labeling with a gold-tagged secondary antibody, and examined under TEM. Diffuse cytoplasmic staining of E. coli for EF-Tu was observed (Figure 6A), and served as a positive control for the antibody. Decalcified NPs were also recognized by the EF-Tu antibody, and staining appeared to localize to the outer border of decalcified NPs (Figure 6B) rather that the inner core (see Figure 1C). NP labeling was absent when the primary antibody was omitted (not shown).

Figure 6. Identification of EF-Tu by TEM.

Localization of immunogold-labeled antibodies to EF-Tu in E. coli used as a positive control (Panel A) and decalcified biologic NPs derived from a human kidney stone (Panel B). Labeling was not observed in samples when the primary antibody was omitted (not shown).

Flow cytometric analysis

In a proof of principle experiment designed to quantitate NPs, flow cytometric scatter blot analysis showed that 85–90% of decalcified NPs were less than 500 nm in diameter, with 10–15% greater than 500 nm in diameter (Figure 7B). Fluorescence dot blots analyses demonstrated that less than 10% of decalcified NPs were positive for human EF-Tu antibody (Figure 7C). There were no positive counts in samples treated with Streptavidin-PE alone without EF-Tu antibody (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Decalcified biologic NPs (100–200 nm) derived from a human kidney stone detected by flow cytometry.

Representative scatter dot plots of reagents (twice filtered Hanks'/HEPES buffer pH 7.4 plus biotinylated EF-Tu antibody and Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin (SA-PE) through 0.2μm membrane filter) without NPs (A) and reagents with NPs (B) from FACSCanto™ flow cytometry. P1 is the gate for all events, NPs is the gate for nanoparticles, and the other gates represent those for calibration sizing beads (μ = micron in diameter). In Panel C, a representative fluorescence dot plot is restricted by the NPs scatter gate from Panel B. The quadrant lines dividing EF-Tu positive (Q1) from negative events (Q3) are drawn to include the maximal number of positive events above the events observed with the SA-PE alone control shown in Panel D. FL1= fluorescein-1; FL2= fluorescein-2.

DISCUSSION

In order to define the biochemical composition of calcified NPs, it was necessary to define appropriate methods to remove the calcium shell. Treatment with 0.5M EDTA overnight or 0.5N HCl for 5 min each decalcified NPs as verified by spectral analysis and Alizarin Red S staining, which provides a rapid method to verify decalcification. After complete decalcification an inner core composed of proteins remains. However, calcification seems to be necessary for NP assembly, since NPs do not develop under conditions that do not physicochemically support calcium phosphate crystallization (low calcium and low pH). Therefore, biologic NP assembly seems to arise from a complex interplay of protein assembly and calcium phosphate deposition.

Several groups have defined proteins that are associated with NPs derived from other sources, including albumin, Fetuin A, Fetuin B and Fetal Hemoglobin, and these appear most likely derived from the serum in the culture media (3, 4). The present results confirm and extend these observations by identifying the major proteins in the core of NPs obtained from human aneurysms and calcium kidney stones, including EF-Tu, EF-G, Fructose binding aldolase, and Chaperone C1pB of apparent microbial origin (Table 2). Other proteins derived from bovine serum in the culture media, i.e., Fetuin A, Fetuin B and Fetal Hemoglobin were also detected, as has been previously reported by others (3). However, it is unlikely that the EF-Tu identified in these studies came directly from the culture serum since it had no homology to bovine isoforms, but nearly complete homology to prokaryotic forms. The molecular weight of many proteins in Table 2 approximated that of the band from which they were sequenced, however others were substantially larger. Therefore they may have formed multimers or aggregates with other proteins, despite the reducing conditions employed.

Furthermore, MS/MS analysis of the major component of the 2 most prominent bands confirmed nearly 100% sequence homology with EF-Tu from Staphylococcus epidermidis. On western blot analysis a 43kDa polypeptide band corresponding to EF-Tu was found in HA399, A2 and AP11 NPs and also in E. coli. However, it was absent in fetal bovine serum and hydroxyapatite crystals incubated in fetal bovine serum. The association of EF-Tu with decalcified NPs was confirmed by TEM using gold-tagged antibodies and FACS using biotinylated antibodies. Earlier studies had demonstrated a similar band at 39kDa that was identified as EF-Tu (6, 7). At this point the source of this EF-Tu is unclear, but its presence and abundance in NPs suggest it may indeed represent a structural component of the underlying NP core. Therefore, we propose that it could help to define a unique biosignature of calcifying biologic NPs in the future.

EF-Tu is involved in synthesis of bacterial proteins and is a component of bacteriophage Qβ replicase (9) and component of the cytoplasm (70,000 molecules per cell, 5% of the total cellular protein) (10). This highly conserved function and ubiquitous distribution renders the elongation factor a valuable phylogenetic marker among eubacteria and throughout the archaebacterial and eukaryotic kingdom (11). It is also intriguing that purified EF-Tu aggregates readily in vitro and precipitates in the presence of calcium and vinblastine ions (9, 10). Therefore, its presence in isolated and culturable biologic NPs may be driven by calcification, or instead promote their calcification. However, if microbial proteins such as EF-Tu are indeed incorporated into the NPs during crystallization (due to their affinity for calcium), it is unclear what their ultimate source is since we could not confirm that they were present in the serum used in these experiments. The presence of bacterial products in propagated NPs is not without precedence as remnant sequences of bacterial DNA have been defined in NP biofilm derived from saliva, bovine and human blood (2).

Current evidence suggests that the matrix which holds biological NPs together is a complex mixture of minerals (calcium and phosphorus) and macromolecules, including proteins identified in this study (3, 4, 6, 7, 12). Previous studies have also demonstrated the presence of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids (6, 7). Although, it has been known for many years that NPs produce a mineral shell through an undescribed mechanism, and the shell increases in size of thickness over time (13), our studies suggest this shell grows atop an inner structure that can exist independently and contains conserved proteins including EF-Tu (12) which might prove valuable as a probe to track their presence in biologic specimens.

Previous studies have confirmed that BacLight Green, a proprietary bacterial stain available from Molecular Probes, labels NPs when they are present in a biofilm (12). Similarly, the lectin concanavalin A, a marker for bacterial biofilm exopolysaccharides, also stains NPs in vitro (12). Advanced digital flow cytometry can be used for NP analysis. The low percentage (10–15%) of decalcified NPs that appeared greater than 500 nm in size by flow cytometry scatter dot blot (Figure 7B) may represent NP aggregates. Flow cytometric analysis also detected only small percentage (8%) of decalcified NPs as EF-Tu positive (Figure 7C). TEM images, however, suggest that some of the protein may lie deeper within the NP core (Figure 6) and thus, not detected by flow cytometry. Nevertheless, these studies suggest it is possible that a panel of probes could be used to characterize the presence of NPs. These probes could be used to identify nanoparticles in biologic fluids such as blood or urine as a diagnostic test for ongoing calcification processes in soft tissues. It is even possible that probes could be tagged in order to detect nanoparticles deposited in soft tissues in vivo.

The origin and classification of biologic NPs remain controversial. Are they simply a physicochemical phenomena? Recent reports strongly argue this point of view (3). Our body of work suggests a more complicated and nuanced answer. Indeed, many components that comprise NPs come from bovine serum. Yet others are clearly not (e.g., EF-Tu). Where do the prokaryotic proteins such as EF-Tu come from? Are they trace contaminants of bovine serum? Or are they remnants of microbes present in the donor tissue (12). Are they in some fashion concentrated in the NPs? Or instead is the EF-Tu an integral component of NPs involved in ongoing biosynthesis? One limitation of our current study is that the NPs were propagated in bovine serum-containing medium before the proteomic evaluations making it difficult to differentiate which proteins were in the original biologic specimen and which were derived from the serum. Therefore, alternative culture methods which eliminate the bovine proteins are needed as well as monoclonal antibodies against EF-Tu from Staphylococcus as opposed to human. Even if these biologic NPs are a biochemical phenomenon, our studies also strongly suggest they have pathologic potential, and can, for example, accelerate atherosclerotic reactions at the site of injury (14, 15). Therefore, further study into the biologic nature of these particles is of great interest and importance.

In conclusion, we have defined methods to decalcify culturable, biologic NPs, and identified key components of their proteome. These elements including EF-Tu can be used as biomarkers to further define processes that mediate propagation of biologic NPs and perhaps can be used to identify processes involved in calcification of mammalian soft tissues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge research support from the National Institutes of Health (DK 60202 and HL 88988), the John E. Fetzer Memorial Trust, and the Ministry of Education and Science Technology (R13-2007-019-00000-0), Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller VM, Rodgers G, Charlesworth JA, Kirkland B, et al. Evidence of nanobacterial-like structures in calcified human arteries and cardiac valves. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1115–1124. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00075.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cisar JO, Xu D-Q, Thompson J, Swaim W, et al. An alternative interpretation of nanobacteria-induced biomineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2000;97:11511–11515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young JD, Martel J, Young L, Wu CY, et al. Putative nanobacteria represent physiological remnants and culture by-products of normal calcium homeostasis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raoult D, Drancourt M, Azza S, Nappez C, et al. Nanobacteria Are Mineralo Fetuin Complexes. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science. 2006;311:622–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1114397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khullar M, Sharma SK, Singh SK, Bajwa P, et al. Morphological and immunological characteristics of nanobacteria from human renal stones of a north Indian population. Urol Res. 2004;32:190–195. doi: 10.1007/s00240-004-0400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar V, Farell G, Yu S, Harrington S, et al. Cell biology of pathologic renal calcification: contribution of crystal transcytosis, cell-mediated calcification, and nanoparticles. J Investig Med. 2006;54:412–424. doi: 10.2310/6650.2006.06021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benzerara K, Miller VM, Barell G, Kumar V, et al. Search for microbial signatures within human and microbial calcifications using soft x-ray spectromicroscopy. J Investig Med. 2006;54:367–379. doi: 10.2310/6650.2006.06016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck BD, Arscott PG, Jacobson A. Novel properties of bacterial elongation factor Tu. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:1250–1254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.3.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson GR, Rosenbusch JP. Abundance and membrane association of elongation factor Tu in E. coli. Nature. 1976;261:23–26. doi: 10.1038/261023a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ke D, Boissinot M, Huletsky A, Picard FJ, et al. Evidence for horizontal gene transfer in evolution of elongation factor Tu in enterococci. Journal of bacteriology. 2000;182:6913–6920. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.6913-6920.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz MK, Hunter LW, Huebner M, Lieske JC, et al. Characterization of biofilm formed by human-derived nanoparticles. Nanomedicine (London, England) 2009;4:931–941. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kajander EO, Ciftcioglu N. Nanobacteria: an alternative mechanism for pathogenic intra- and extracellular calcification and stone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8274–8279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz MA, Lieske JC, Kumar V, Farell-Baril G, et al. Human-derived nanoparticles and vascular response to injury in rabbit carotid arteries: proof of principle. International journal of nanomedicine. 2008;3:243–248. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz MK, Lieske JC, Hunter LW, Miller VM. Systemic injection of planktonic forms of mammalian-derived nanoparticles alters arterial response to injury in rabbits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1434–1441. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00993.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]