Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) in adults is a common cause of dizziness seen in general practice with a 1-year prevalence of 1.6%.1 It is characterised by brief episodes of dizziness or vertigo typically triggered by rapid changes in the position of the head and can be associated with nausea which may persist.2 BPPV can resolve spontaneously within weeks or months.2 It can present in clusters and can recur after remission.2 This short paper is based on a critical literature review.

DIAGNOSING BPPV

GPs can confirm a diagnosis of BPPV using the Dix-Hallpike test.2,3 The patient is moved quickly ‘from a sitting position to lying with the head tipped 45° below the horizontal, 45° to the side, and with the side of the affected ear (and semicircular canal) downwards.’2 The Dix-Hallpike test is positive when torsional (rotatory) nystagmus occurs when the head is turned to the affected ear.4 In a prospective study of diagnosis of vertigo in general practice, a positive Dix-Hallpike test had a positive predictive value of 83.3% and a negative predictive value of 52% in diagnosing BPPV.3 Having done so, GPs can then usually resolve the condition through a manipulation called the Epley manoeuvre.

EPLEY MANOEUVRE

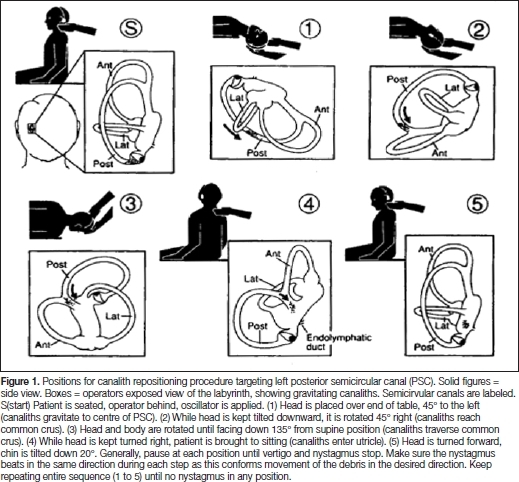

The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre is a ‘safe and effective treatment’ for BPPV.2 It consists of ‘a series of four quick movements of the head and body from sitting to lying, rolling over, and back to sitting (Figure 1). Each position is maintained until positional nystagmus has disappeared, indicating cessation of endolymph flow’.4 The Epley manoeuvre has been shown to be beneficial after one session when 77% of patients reported effective relief and an additional 20% of patients reported the same the following week after the second session.4 Patients are advised to perform self-treatment at home after receiving the Epley manoeuvre.4

Figure 1.

The Epley manoeuvre for treating benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. This article was published in Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, 107(3), Epley JM, The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, 399–404, Copyright Elsevier 1992.

IS IT FEASIBLE TO IMPLEMENT THE EPLEY MANOEUVRE IN GENERAL PRACTICE?

The Epley manoeuvre in general practice produces similar results when implemented in secondary or tertiary centres.5 A randomised, prospective, double-blind, sham-controlled study determined whether the Epley manoeuvre is effective for treating BPPV in primary care.5 At baseline the intervention group received the Epley manoeuvre and the control group received a sham manoeuvre which consisted of the Epley manoeuvre performed on the unaffected side.5 At 1 week and 2 weeks both groups received the Epley manoeuvre.6 Initial improvement was statistically significant, as after the first treatment 34.2% of patients in the intervention group had a negative Dix-Hallpike test, compared with 14.6% in the control group (P value = 0.04; 95% CI = 1.03 to 5.33).5 This study concluded that the number of patients who were successfully treated with the first Epley manoeuvre was statistically significant compared to the control group, and that GPs could use the Epley manoeuvre to treat BPPV.5

Glasziou suggested that the Epley manoeuvre has been slow to be implemented into primary care because of the level of skill involved and a lack of confidence with the Dix-Hallpike test and the Epley manoeuvre.1 This can be addressed with training; for example, using a video showing the Dix-Hallpike test and Epley manoeuvre.1 It is useful to have another member of staff to assist when carrying out the test and the manoeuvre. The staffing implications need to be considered.

In a 10-minute consultation, a GP could take a history and perform Rinne's and Weber's tests followed by the Dix-Hallpike test and the Epley manoeuvre.

CONCLUSION

The evidence suggests that BPPV can be diagnosed and subsequently treated with the Epley manoeuvre in general practice with great effect, thus reducing referrals to specialist centres. If the patient subsequently presents with unresolved symptoms they should then be referred. Further research needs to be undertaken to measure the effectiveness of the Epley manoeuvre in general practice through further randomised controlled trials. Avoiding long-term medication, and the consequent side effects, is another aspect of the cost-effectiveness of the manoeuvre.

The research evidence suggests this diagnostic manoeuvre and manipulation can be readily and successfully adopted in primary care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glasziou P, Heneghan C. Epley and the slow boat from research to practice. Evid Based Med. 2008;13:34–35. doi: 10.1136/ebm.13.2.34-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003162.pub2. CD003162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanley K, O’ Dowd T. Symptoms of vertigo in general practice: a prospective study of diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:809–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lempert T, Gresty MA, Bronstein AM. Fortnightly Review: Benign positional vertigo: recognition and treatment. BMJ. 1995;311:489–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7003.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munoz JE, Miklea JT, Howard M, et al. Canalith repositioning maneuver for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo Randomized controlled trial in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1048–1053. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]