RasC controls the spatial and temporal activity of TORC2 to regulate directional cell migration.

Abstract

In chemotactic cells, G protein–coupled receptors activate Ras proteins, but it is unclear how Ras-associated pathways link extracellular signaling to cell migration. We show that, in Dictyostelium discoideum, activated forms of RasC prolong the time course of TORC2 (target of rapamycin [Tor] complex 2)-mediated activation of a myristoylated protein kinase B (PKB; PKBR1) and the phosphorylation of PKB substrates, independently of phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-trisphosphate. Paralleling these changes, the kinetics of chemoattractant-induced adenylyl cyclase activation and actin polymerization are extended, pseudopodial activity is increased and mislocalized, and chemotaxis is impaired. The effects of activated RasC are suppressed by deletion of the TORC2 subunit PiaA. In vitro RasCQ62L-dependent PKB phosphorylation can be rapidly initiated by the addition of a PiaA-associated immunocomplex to membranes of TORC2-deficient cells and blocked by TOR-specific inhibitor PP242. Furthermore, TORC2 binds specifically to the activated form of RasC. These results demonstrate that RasC is an upstream regulator of TORC2 and that the TORC2–PKB signaling mediates effects of activated Ras proteins on the cytoskeleton and cell migration.

Introduction

Chemotaxis, the capacity of cells to migrate directionally in response to gradients of extracellular chemical cues, plays an important role in many biological processes, including embryogenesis, neuronal patterning, wound healing, and immune cell trafficking. Conversely, improper chemotaxis underlies various pathological conditions, including many chronic inflammatory diseases. Altered cell motility is a hallmark of transformed cells, and chemotactic homing assists in the migration of cancer cells from primary tumors to metastatic sites.

Studies of the model organism Dictyostelium discoideum have greatly contributed to our understanding of eukaryotic chemotaxis. In D. discoideum, chemoattractant gradients detected by G protein–coupled receptors are converted into localized intracellular signals to direct cell migration (Franca-Koh et al., 2006; Iglesias and Devreotes, 2008; King and Insall, 2009). For example, phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) at the leading edge of chemotaxing cells promotes cytoskeleton rearrangements possibly by recruiting pleckstrin homology (PH) domain–containing proteins such as PKB A (PKBA; Parent et al., 1998; Meili et al., 1999). We have recently described a circuit involving TORC2 (target of rapamycin [Tor] complex 2) and its substrate PKBR1 that functions in parallel with the PIP3 pathway to regulate chemotaxis (Kamimura et al., 2008). Unlike PKBA, PKBR1 is tethered to the plasma membrane via the N-terminal myristoylation (Meili et al., 2000). With uniform chemoattractant stimulation, both PKBA and PKBR1 are transiently phosphorylated within their hydrophobic motifs (HMs) via TORC2 and subsequently phosphorylated within their activation loops (ALs) by phosphoinositide-dependent kinases (PDKs; Fig. 1 A; Kamimura et al., 2008; Kamimura and Devreotes, 2010). The HM phosphorylation is essential for the activation of PKBR1 and also contributes to the activation of PKBA. In migrating cells, these phosphorylation events are restricted to the cell’s leading edge (Kamimura et al., 2008).

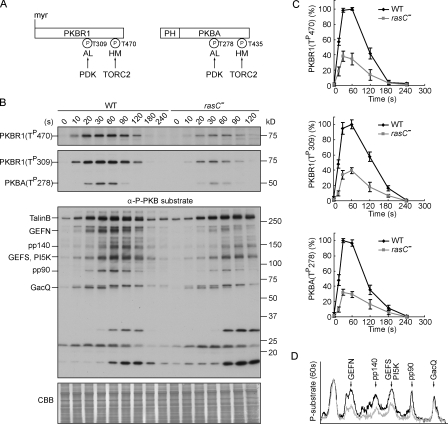

Figure 1.

RasC is required for the activation of the PKB pathway. (A) Schematic representation of the activation of PKBR1 and PKBA. PKBR1 is tethered to the plasma membrane via myristoylation, whereas PKBA is recruited to the plasma membrane by PIP3 via the PH domain. Upon chemoattractant stimulation, the two PKBs are activated through phosphorylation of their HMs by TORC2 and ALs by PDK. (B) Wild-type (WT) or rasC− cells were stimulated with cAMP, sampled at the indicated time points, and probed with anti–phospho-HM (first panel), anti–phospho-AL (second panel), or anti–phospho-substrate antibodies (third panel). The protein-transferred membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) and shown as loading control (forth panel). Seven proteins, including TalinB, GEFN, GEFS, PI5K, and GacQ, are confirmed PKB substrates. Note that TalinB co-migrates with a non-PKB substrate band, and unmarked bands at the bottom part of the third panel are not PKB substrates (Kamimura et al., 2008). (C) Quantitative densitometry of the first and second panels of B, showing the mean intensity ± SD of the respective bands from three independent experiments. (D) Densitometric scan of the 60-s lanes of the third panel of B (wild type, black line; rasC−, gray line).

These observations suggest that the activity of TORC2 is both temporally and spatially regulated in chemotactic cells, and similarly, the catalytic activity of mammalian TORC2 is reported to be stimulated by growth factors (Sarbassov et al., 2005; Frias et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2008). Although the TORC2 regulators are unidentified, several lines of evidence have suggested that the Ras family small GTPases may play a role. Ras proteins are activated by chemoattractant in D. discoideum with time courses that parallel TORC2 activation (Kae et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2008). The D. discoideum TORC2 subunit Rip3 and its yeast and mammalian homologues all contain a putative Ras-binding domain (RBD). Rip3 interacts with the GTP-bound form of D. discoideum RasG and human H-Ras in yeast two-hybrid assays (Lee et al., 1999, 2005). In a cell-free system that we previously developed, GTP-γS is able to trigger TORC2-mediated activation of PKBR1 (Kamimura et al., 2008). Though suggestive, these observations do not prove that Ras proteins directly regulate TORC2, and indeed, there are several inconsistencies. For example, disruption of RasG has little or no effect on PKB phosphorylation or chemotaxis (Sasaki et al., 2004; Kamimura et al., 2008).

In this study, we use a combination of genetic interaction strategies and in vitro reconstitution assays to determine whether Ras family proteins activate TORC2 and to examine the effects of this putative pathway on directed cell migration and chemotactic responsiveness. We report that a specific Ras protein, RasC, activates TORC2 and exerts temporal and spatial control on the TORC2–PKBR1 pathway to regulate chemotaxis.

Results

RasC is required for TORC2-mediated activation of PKB

Pursuing our earlier observation suggesting that Ras proteins may regulate the two PKBs (Kamimura et al., 2008), we examined PKB activity in cells in which different Ras genes were disrupted. In wild-type cells, cAMP triggered rapid phosphorylation of the HM of PKBR1 and the ALs of PKBR1 and PKBA, which peaked at 30–60 s and declined to the prestimulus level by 2–3 min (Fig. 1 B). Consequently, a series of PKB substrates were also transiently phosphorylated (Fig. 1 B). We previously found that these phosphorylations were reduced in rasC−/rasG− but not in rasG− cells, suggesting that either RasC or both Ras proteins are needed (Fig. S1 A; Kamimura et al., 2008). In this study, we show that, compared with wild-type cells, phosphorylations of the HM of PKBR1 and the ALs of PKBR1 and PKBA were reduced by 60–70% by deleting RasC alone (Fig. 1, B and C; and Fig. S1 B). There was also a significant reduction in the phosphorylation of many PKB substrates (Fig. 1 D). Expression of Flag-tagged RasC in rasC− cells restored all of these phosphorylation events (data described in the next paragraph). These results suggest that RasC is a regulator of the PKB pathway. However, because of the residual phosphorylation of the PKBs and PKB substrates present in rasC− cells, which may be due to the presence of other chemoattractant-activated Ras proteins (Fig. S1 C), and the fact that rasC− cells display better chemotaxis compared with cells lacking the two PKBs (Meili et al., 1999, 2000; Lim et al., 2001; Kamimura et al., 2008), further evidence is needed to prove this hypothesis.

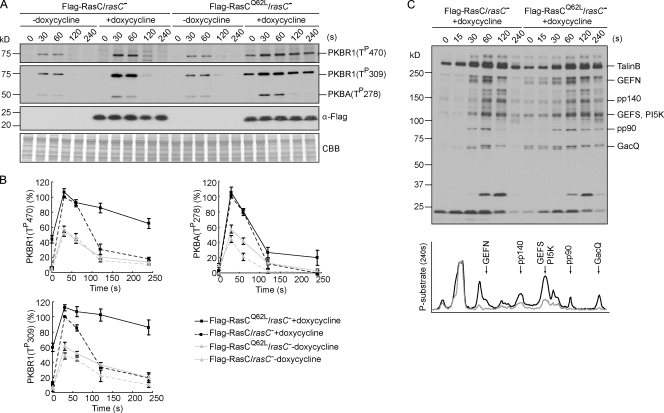

We reasoned that if RasC indeed regulates the PKB pathway, the kinetics of PKB phosphorylation might be changed by altering the lifetime of RasC activation. To assess this possibility, we expressed Flag-tagged wild-type or activated form of RasC (RasCQ62L) in rasC− cells under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter. An equivalent mutation (Q61L) in human H-Ras was reported to have both increased nucleotide exchange and decreased GTPase activity (Feig and Cooper, 1988), and indeed, we found RasCQ62L to be persistently activated (unpublished data). The expression of Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L was not detectable before doxycycline induction (Fig. 2 A). Consequently, the Flag-RasC/rasC− and -RasCQ62L/rasC− cells exhibited reduced PKB phosphorylation similar to rasC− cells (compare Fig. 2 [A and B] with Fig. 1 [B and C]). 2–3 h after induction, the levels of Flag-RasC and -RasCQ62L reached 3.9 ± 0.9– and 2.6 ± 0.4–fold of the level of endogenous RasC in wild-type cells (Fig. 2 A and not depicted). The expression of Flag-RasC restored the phosphorylation of PKBR1 and PKBA to near wild-type patterns (compare Fig. 2 [A and B] with Fig. 1 [B and C]). The expression of Flag-RasCQ62L also restored the phosphorylation events, but for the HM and AL of PKBR1, it elevated the basal level and greatly extended the kinetics (Fig. 2, A and B). The half-life of HM phosphorylation of PKBR1 was ∼40 s in cells expressing Flag-RasC but was extended to ∼140 s in cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L. The half-life of AL phosphorylation of PKBR1 was similarly prolonged. In contrast, AL phosphorylation of PKBA was negligibly changed in the presence of Flag-RasCQ62L, although the profile sometimes remained slightly elevated at later time points (Fig. 2, A and B). Consistent with our previous finding that PKBR1 provides the primary PKB activity (Kamimura et al., 2008), many PKB substrates remained in their phosphorylated state at later time points in Flag-RasCQ62L–expressing cells (Fig. 2 C). Similar results were obtained when Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L was expressed in rasC− cells using a noninducible promoter (Fig. S2, A–C). We also found that the expression of Flag-tagged RasCG13V, another activated form of RasC, modestly lengthened the activation of PKBR1 (Fig. S2 D). The extended kinetics of PKBR1 phosphorylation correlated with the slow turn-off of RasC caused by Q62L and G13V mutations, indicating that the transient activation of RasC sets the time course of the PKB pathway. In contrast, the expression of activated form of RasG (RasGQ61L) did not affect PKB phosphorylation (Fig. S1 D), again suggesting a specific role for RasC in regulating the PKB pathway.

Figure 2.

Persistently activated RasC alters the time course of PKBR1 and PKB substrate phosphorylation. (A) Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L was expressed under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter in rasC− cells. Cells developed in the presence or absence of doxycycline were stimulated with cAMP, sampled at the indicated time points, and probed with phospho-specific antibodies or anti-Flag antibody. The protein-transferred membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) and shown as loading control. (B) Quantitative densitometry of the first and second panels of A, showing the mean intensity ± SD of the respective bands from four independent experiments. (C) Samples were probed with anti–phospho-substrate antibody (top). Densitometric scans of the 240-s lanes are shown in bottom panel (Flag-RasC, gray line; Flag-RasCQ62L, black line).

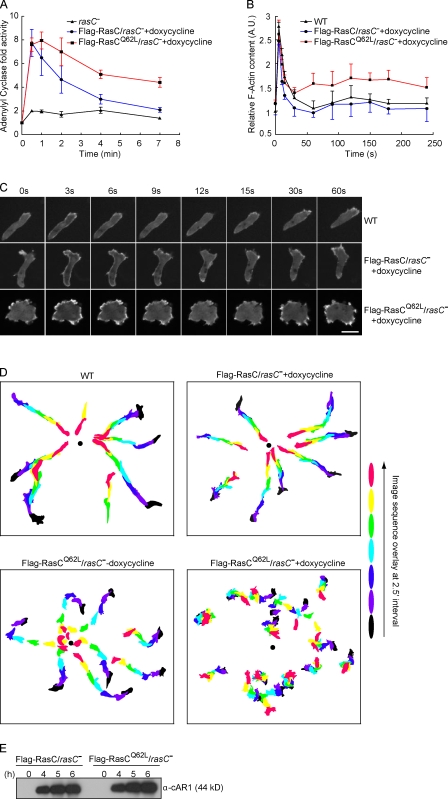

Proper temporal and spatial regulation of the PKBR1 pathway is critical for chemotaxis

To assess the effect of prolonged activation of RasC and PKB signaling, we analyzed a series of chemotactic responses as well as chemotaxis in rasC− cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. We first measured the cells’ capacity to activate adenylyl cyclase (ACA) in response to chemoattractant stimulation because RasC (Lim et al., 2001), TORC2 (Chen et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2005), and the two PKBs (Fig. S3) are all required for the activation of the enzyme. Similar to wild-type cells, the Flag-RasC–expressing cells displayed a rapid rise in ACA activity, peaking at 30 s after the addition of cAMP, followed by a return to the prestimulus level with a half-time of ∼1.8 min (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, the half-time of decline was prolonged to ∼5 min in cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L (Fig. 3 A). As a control, in the absence doxycycline, the Flag-RasC/rasC− and -RasCQ62L/rasC− cells showed greatly reduced ACA activation (not depicted) similar to rasC− cells (Fig. 3 A).

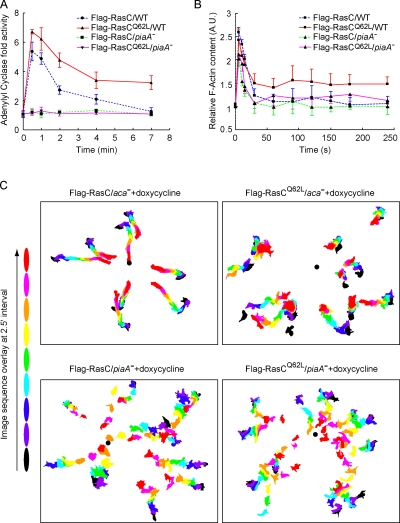

Figure 3.

Chemotactic responses are altered in cells with prolonged PKBR1 signaling. (A) ACA activation upon uniform cAMP stimulation was measured in rasC− cells or rasC− cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. The data represent the range (mean ± standard error) of two independent experiments. The basal activities ranged from 1.9 pmol/min/mg protein for rasC− to 2.5 pmol/min/mg protein for Flag-RasC/rasC− and 3.8 pmol/min/mg protein for Flag-RasCQ62L/rasC− cells. (B) Actin polymerization was measured in wild-type (WT) cells or rasC− cells expressing Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. Cells were stimulated with cAMP and lysed with Triton X-100 buffer. The Triton-insoluble pellet fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The amount of actin in the pellet was quantified by densitometry. The data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. A.U., arbitrary unit. (C) The translocation of LimEΔcoil-RFP was recorded by fluorescence microscopy with images taken every 3 s. Frames from the indicated time points after the addition of cAMP are shown. (D) The chemotactic movements to a micropipette releasing 1 µM cAMP (black dot) were recorded by time-lapse microscopy. Images from frames at 2.5-min intervals were processed to outline the cells, color coded for each time point, and overlaid. (E) The expression of cAR1 is comparable in rasC− cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. At the indicated time points after initiation of development, CHAPS-insoluble membrane fractions were prepared as described previously (Xiao et al., 1997) and probed with anti-cAR1 antibody. Bar, 10 µm.

We next monitored chemoattractant-induced changes in actin polymerization and the distribution of the actin-binding protein LimEΔcoil, which labels newly formed F-actin (Schneider et al., 2003). In wild-type cells and rasC− cells expressing Flag-RasC, uniform exposure to chemoattractant triggered two phases of actin polymerization (Fig. 3 B). An initial large peak occurred within a few seconds, followed by a rapid decrease and a subsequent lower peak centered around 2 min. Paralleling these changes, LimEΔcoil-RFP first translocated uniformly to the cell cortex, then returned to the cytosol as cells rounded up, and finally localized to regions of newly formed pseudopods during the second phase (Fig. 3 C and Video 1). Compared with these two cell lines, cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L exhibited elevated F-actin polymerization, especially in the second phase (Fig. 3 B). When observed under the microscope, the cells were less polarized and displayed an increased number of F-actin–rich membrane protrusions (Fig. 3 C and Video 2).

We then compared the chemotactic behavior of wild-type cells and cells expressing Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L (Fig. 3 D and Table I). When placed in chemoattractant gradients generated by a micropipette releasing cAMP, wild-type cells rapidly polarized and migrated toward the higher concentrations with a focused leading edge (Video 3). Without doxycycline, the chemotactic responses of Flag-RasC/rasC− (not depicted) and -RasCQ62L/rasC− cells were slightly affected compared with wild-type cells (Video 4). After induction with doxycycline, Flag-RasC–expressing cells migrated robustly toward the micropipette with motility and chemotactic parameters equivalent to wild-type cells (Video 5). In contrast, cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L showed reduced directionality to the chemoattractant source. They displayed selective defects in chemotactic index, chemotactic motility, and persistency compared with the other cell lines (Video 6). The chemotaxis defect in these cells was not caused by a delay in cell differentiation, as the expression of the cAMP receptor, cAR1, was not impacted (Fig. 3 E). A chemotaxis defect was also observed when Flag-RasCQ62L was expressed in the rasC− cells using a noninducible promoter (Fig. S2, E and F), although cAR1 expression was partially impaired in these cells (not depicted). Collectively, these results imply that the failure to temporally control PKBR1 activation alters the chemotactic responsiveness of cells expressing RasCQ62L and prevents them from performing directional migration efficiently.

Table I.

Quantification of cellular behavior

| Strain | Motility speed | Chemotax motility | Chemotax index | Persistency |

| μm/min | μm/min | |||

| Wild type | 7.13 ± 0.53 | 6.04 ± 1.07 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.87 ± 0.08 |

| Flag-RasC/rasC− + doxycycline | 7.75 ± 1.39 | 6.30 ± 1.22 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.83 ± 0.01 |

| Flag-RasCQ62L/rasC− − doxycycline | 6.55 ± 0.98 | 5.20 ± 0.91 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.05 |

| Flag-RasCQ62L/rasC− + doxycycline | 5.10 ± 1.78 | 1.06 ± 0.52 | 0.09 ± 0.25 | 0.31 ± 0.15 |

| Flag-RasC/aca− + doxycycline | 4.62 ± 0.47 | 3.94 ± 0.53 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.06 |

| Flag-RasCQ62L/aca− + doxycycline | 3.94 ± 0.49 | 0.77 ± 0.24 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | 0.46 ± 0.04 |

| Flag-RasC/piaA− + doxycycline | 5.68 ± 1.14 | 2.92 ± 0.71 | 0.46 ± 0.03 | 0.60 ± 0.08 |

| Flag-RasCQ62L/piaA− + doxycycline | 5.24 ± 0.37 | 2.79 ± 0.16 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 0.56 ± 0.01 |

| Flag-RasCQ62L/piaA− − doxycycline | 5.59 ± 0.65 | 3.04 ± 0.45 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.04 |

Quantitation of the chemotactic behavior of at least 10 cells from at least three independent experiments. Motility and chemotactic parameters are calculated as described in Materials and methods. The data represent mean ± SD.

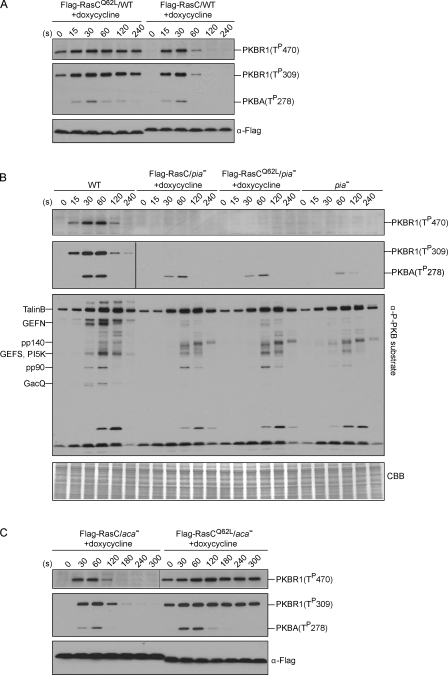

The effects of activated RasC on chemotactic responses and chemotaxis are suppressed in piaA− cells

If the aberrant chemotactic behavior displayed in RasCQ62L-expressing cells results from the unregulated PKBR1 activity, these responses should be suppressed in cells in which the prolonged PKBR1 activation is blocked. To test this, we expressed Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L in cells lacking the essential TORC2 component PiaA and compared the chemotactic responses of these cells with wild-type controls. Deletion of PiaA did not impair the activation of RasC (Fig. S4). Wild-type cells induced to express Flag-RasCQ62L exhibited prolonged phosphorylation of PKBR1 (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, in piaA− or piaA− cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L, chemoattractant-triggered phosphorylation of PKBR1 was abolished, and phosphorylations of PKBA and PKB substrates were reduced (Fig. 4 B). Consistent with our hypothesis, deletion of PiaA prevented the extended ACA activation and actin polymerization responses observed in wild-type controls expressing Flag-RasCQ62L (Fig. 5, A and B).

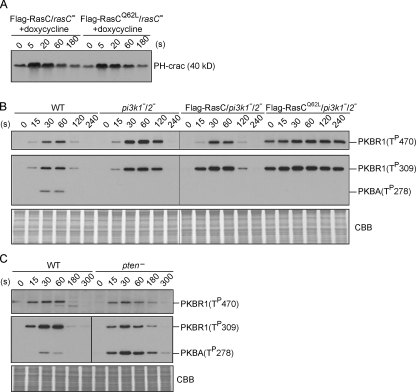

Figure 4.

Deletion of the TORC2 component PiaA suppresses the prolonged phosphorylation of PKBR1 and PKB substrates caused by RasCQ62L. (A–C) Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L was expressed under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter in wild-type (WT; A), piaA− (B), or aca− cells (C). Cells were stimulated with cAMP, sampled at the indicated time points, and probed with phospho-specific antibodies or anti-Flag antibody. The protein-transferred membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) and shown as loading control. Vertical black lines indicate that intervening lanes have been spliced out.

Figure 5.

Deletion of PiaA suppresses the unregulated chemotactic responses caused by RasCQ62L. (A and B) ACA activation and actin polymerization were measured in wild-type (WT) or piaA− cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. ACA data represent the range (mean ± standard error) of two independent experiments. The basal activities ranged from 15.2 pmol/min/mg protein for Flag-RasC/piaA− and -RasCQ62L/piaA− cells to 17.9 pmol/min/mg protein for Flag-RasC/WT and 19.2 pmol/min/mg protein for Flag-RasCQ62L/WT cells. For the actin polymerization assay, the data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. A.U., arbitrary unit. (C) The micropipette assay was performed in aca− or piaA− cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L.

We then performed the micropipette assay on these cells. Because ACA activity was dramatically reduced in piaA− cells (Fig. 5 A), we chose aca− cells, which have been reported to display robust chemotaxis (Kriebel et al., 2003), as controls. Similar to rasC− cells, expressing Flag-RasCQ62L in aca− cells disrupted the normal transient kinetics of phosphorylation of PKBR1 (Fig. 4 C), and the cells displayed greatly reduced chemotaxis compared with aca− cells expressing Flag-RasC (Fig. 5 C, Table I, and Videos 7 and 8). This result incidentally shows that the deleterious effects of RasCQ62L on chemotaxis are not mediated through elevated cAMP. Deletion of PiaA suppressed the chemotaxis defects caused by RasCQ62L. Although partially impaired, piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L showed comparable motility and chemotactic parameters compared with piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasC (Fig. 5 C, Table I, and Videos 9 and 10). These results present a strong genetic link between RasC and TORC2 and imply that RasC acts through TORC2 to control PKBR1 and chemotaxis.

PIP3 is not required for RasC-mediated activation of PKBR1

In many systems, phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) are effectors of Ras proteins, and PIP3 recruits Akt/PKB to the plasma membrane and facilitates its activation (Cantley, 2002; Karnoub and Weinberg, 2008). However, only PKBA, but not PKBR1, contains a PIP3-responsive PH domain. Therefore, we investigated whether the prolonged activation of PKBR1 in Flag-RasCQ62L–expressing cells depends on PI3K. As shown in Fig. 6 A, the time course of PIP3 production upon chemoattractant stimulation was essentially identical in cells expressing Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L, indicating that RasCQ62L does not activate PI3K. Next, we expressed Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L in pi3k1−/2− cells. Because these cells contain no detectable PIP3 (Huang et al., 2003), AL phosphorylation of PKBA was completely abolished (Fig. 6 B). In contrast, Flag-RasCQ62L increased the basal level and prolonged the time course of HM and AL phosphorylation of PKBR1 (Fig. 6 B), as it did in wild-type cells (Fig. 4 A). In addition, we compared the kinetics of PKBR1 phosphorylation in wild-type cells and cells lacking the phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue on chromosome 10), in which the chemoattractant-triggered production of PIP3 is greatly extended (Iijima and Devreotes, 2002; Zhang et al., 2008), and found no significant difference (Fig. 6 C). In contrast, AL phosphorylation of PKBA was increased in pten− cells (Fig. 6 C). Together, these results demonstrate that PIP3 is not required for the prolonged activation of PKBR1 triggered by RasCQ62L.

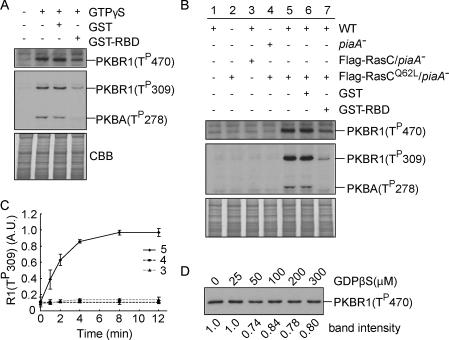

Figure 6.

PIP3 is not required for RasC-mediated activation of the TORC2–PKBR1 pathway. (A) PHcrac-GFP translocation assay, which measures PIP3 content on the membrane, was performed in rasC− cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. (B) Phosphorylation of PKB was measured in wild-type (WT), pi3k1−/2−, and pi3k1−/2− cells expressing Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. The protein-transferred membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) and shown as loading control. (C) Phosphorylation of PKB was measured in wild-type and pten− cells. The protein-transferred membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and shown as loading control. (B and C) Vertical black lines indicate that intervening lanes have been spliced out.

RasC activates TORC2 to phosphorylate PKBR1 in in vitro reconstitution assays

We used a cell-free system to further elucidate the role of RasC in activation of the TORC2–PKB pathway. The HM of PKBR1 and ALs of both PKBR1 and PKBA were rapidly phosphorylated after the application of GTP-γS to lysates of wild-type cells (Fig. 7 A). The addition of excess GST-tagged RBD but not GST inhibited these GTP-γS–induced phosphorylation events (Fig. 7 A), suggesting that GTP-γS functions through Ras proteins to activate TORC2. To test whether RasC specifically activates TORC2, we also examined PKB phosphorylation in unstimulated lysates (with no chemoattractant or GTP-γS added) from wild-type cells (Fig. 7 B, lane 1), piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L (Fig. 7 B, lane 2), and their mixture (Fig. 7 B, lane 5). We reasoned that if RasC is responsible for TORC2 activation, RasCQ62L from the Flag-RasCQ62L/piaA− cell lysates should be able to activate TORC2 from the wild-type cell lysates to phosphorylate the PKBs. Indeed, recapitulation of PKB phosphorylation was only achieved by mixing the two lysates (Fig. 7 C). The reconstitution of PKB phosphorylation could be inhibited by the addition of GST-RBD (Fig. 7 B, lane 7) but not GST (Fig. 7 B, lane 6). Moreover, PKB phosphorylation could not be reconstituted by the combination of Flag-RasC/piaA− and wild-type cell lysates (Fig. 7, B [lane 3] and C) or Flag-RasCQ62L/piaA− and piaA− cell lysates (Fig. 7, B [lane 4] and C). As a control, we also performed the reconstitution assay in the presence of excessive GDP-βS, which would prevent the activation of any other GTPases if present in the system, and found no significant effect (Fig. 7 D). Together, these results indicate that activated RasC is sufficient to trigger PKB phosphorylation via TORC2.

Figure 7.

RasCQ62L activates TORC2-mediated phosphorylation of PKB in vitro. (A) Wild-type cell lysates were stimulated with GTP-γS alone or in the presence of GST or GST-RBD and then probed with phospho-specific antibodies. The protein-transferred membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) and shown as loading control. (B) The indicated cell lines were mixed, lysed, incubated in the presence or absence of GST or GST-RBD for 12 min, and then probed with phospho-specific antibodies. The protein-transferred membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and shown as loading control. Cells were not stimulated with chemoattractant, nor was GTP-γS added to the reaction. WT, wild type. (C) Quantitative densitometry of the time courses of reactions 3, 4, and 5 of B. The data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. A.U., arbitrary unit. (D) piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L were mixed with wild-type cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of GDP-βS, filter lysed, incubated on ice for 12 min, and then probed with anti–phospho-HM antibody.

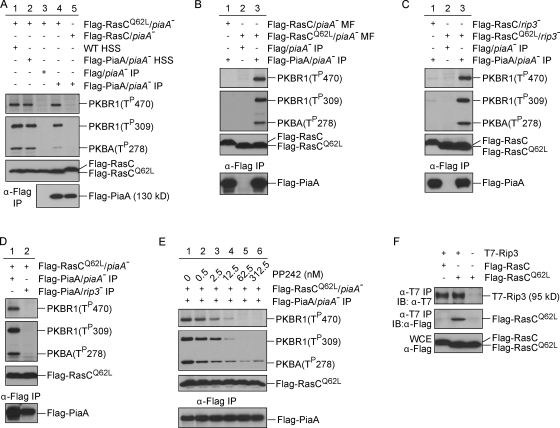

The in vitro system allowed us to further investigate the mechanism of RasC-mediated activation of TORC2. When lysates from wild-type as well as piaA− cells expressing Flag-PiaA were fractionated, the high-speed supernatant (HSS) fractions were found to be able to reconstitute PKB phosphorylation in the presence of RasCQ62L (Fig. 8 A, lanes 1 and 2). Reconstitution could also be achieved with Flag immunoprecipitate from Flag-PiaA/piaA− HSS (Fig. 8 A, lane 4) but not Flag/piaA− HSS (Fig. 8 A, lane 3). However, the Flag-PiaA immunoprecipitate was not sufficient to phosphorylate the two PKBs when added to lysates from piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasC (Fig. 8 A, lane 5). Collectively, these results suggest that the Flag-PiaA immunoprecipitate is likely to contain a TORC2 complex that can be activated by RasCQ62L.

Figure 8.

Reconstitution of PKB activation in vitro with immunopurified TORC2. (A) Cell lysates from piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L were mixed with HSS made from wild-type (WT) cells or piaA− cells expressing Flag-PiaA or with Flag-eluted immunoprecipitate from Flag/piaA− cells or Flag-PiaA/piaA− cells. (B) Membrane fractions (MF) prepared from Flag-RasC/piaA− or Flag-RasCQ62L /piaA− cells were mixed with Flag-eluted immunoprecipitate from Flag/piaA− cells or Flag-PiaA/piaA− cells. (C) Cell lysates from rip3− cells expressing Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L were mixed with Flag-eluted immunoprecipitate from Flag/piaA− cells or Flag-PiaA/piaA− cells. (D) Cell lysates from piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L were mixed with Flag-eluted immunoprecipitate from Flag-PiaA/piaA− cells or Flag-PiaA/rip3− cells. (E) Flag-eluted immunoprecipitate from Flag-PiaA/piaA− cells was treated with increasing concentrations of PP242 before being mixed with cell lysates from piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L. (F) Whole cell extracts were prepared from rip3− cells expressing T7-Rip3 and Flag-RasC, T7-Rip3 and Flag-RasCQ62L, or Flag-RasCQ62L alone. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using anti-T7 antibody, and samples were immunoblotted (IB) with anti-T7 or anti-Flag antibodies.

To further substantiate this conclusion, we tested the reconstituting activity of the Flag-PiaA immunoprecipitate against membrane fractions prepared from piaA− cells as well as total lysates from rip3− cells expressing Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L, all of which are depleted of intact TORC2 complex. We found that the Flag-PiaA immunoprecipitate was able to specifically reconstitute PKB phosphorylation when mixed with membranes isolated from Flag-RasCQ62L/piaA− cells (Fig. 8 B) as well as with lysates from Flag-RasCQ62L/rip3− cells (Fig. 8 C), indicating that the Flag-PiaA immunoprecipitate contains a functional TORC2 complex. Consistent with this finding, we found that Flag-PiaA immunoprecipitated from rip3− cells lacks the reconstituting activity (Fig. 8 D). Furthermore, we found that the ability of the Flag-PiaA immunocomplex to reconstitute PKB phosphorylation depends on TOR activity because it could be blocked by the TOR-specific ATP-competitive inhibitor PP242 (Feldman et al., 2009) with an IC50 of ∼4 nM (Fig. 8 E). Together, these results demonstrate that the RasC–TORC2–PKB pathway can be reconstituted in vitro.

Finally, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation experiment to examine the physical interaction between TORC2 and RasC. To this end, we expressed T7-tagged Rip3 in rip3− cells, which restored the defects of PKB phosphorylation in these cells (unpublished data). We then coexpressed T7-Rip3 with Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L and performed immunoprecipitation with anti-T7 antibody. As shown in Fig. 8 F, Flag-RasC and -RasCQ62L were expressed at comparable levels. However, only Flag-RasCQ62L was specifically immunoprecipitated with T7-Rip3 (Fig. 8 F), indicating that activated RasC interacts either directly with Rip3 or with another component of the TORC2 complex that links to Rip3. This result shows that RasC and TORC2 interact in a regulated fashion and further supports the conclusion that activated RasC is able to stimulate TORC2 activity.

Discussion

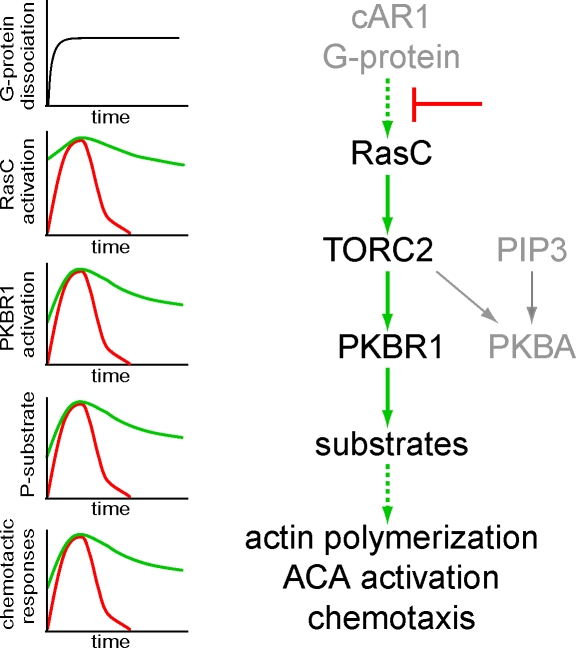

Compared with their widely known function in cell growth, differentiation, and tumorigenesis, the role of Ras proteins in cell motility has been relatively unexplored. In the current work, we performed a series of experiments to investigate how RasC regulates chemotaxis via TORC2. Based on our results, we propose a network of signaling events centered around Ras-mediated activation of TORC2 that controls cytoskeletal activity and chemotaxis. As illustrated in Fig. 9, chemoattractants activate RasC through the G protein–coupled receptor cAR1, leading to TORC2-mediated activation of PKBR1 and PKBA, which phosphorylate PKB substrates and regulate chemotactic responses of the cell. This model is supported by several findings. First, we show that gain of function in RasC results in prolonged phosphorylation of PKBR1 and PKB substrates (Fig. 2), which in turn leads to extended ACA activation, elevated actin polymerization, and impaired chemotaxis (Fig. 3). Second, disruption of TORC2 activity specifically suppresses the aberrant chemotactic responses caused by persistently activated RasC (Figs. 4 and 5). Third, RasC is required for activation of the PKBs in vivo (Fig. 1) and stimulates TORC2-dependent phosphorylation of the PKBs in vitro (Figs. 7 and 8). Fourth, we show that RasC does not activate PI3Ks and that the activation of the TORC2 pathway by RasC does not require PIP3 (Fig. 6). We conclude that there is a RasC–TORC2–PKB pathway in D. discoideum that plays a major role in temporal and spatial regulation of chemotactic responses. This finding has several implications in our understanding of chemotaxis and TORC2 signaling.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of RasC-mediated signaling pathways that control chemotaxis. The chemoattractant cAMP signals through the G protein–coupled receptor cAR1 to RasC, leading to TORC2-mediated activation of PKBR1 and PKBA. The activation of PKBA also depends on recruitment to PIP3. Together, the two PKBs phosphorylate a series of substrates and play a critical role in ACA activation, actin polymerization, and chemotaxis. The graphs to the left schematically illustrate the kinetics of G protein α and βγ subunits dissociation, RasC activation, PKB phosphorylation, PKB substrate phosphorylation, and chemotactic responses. The red line shows the typical wild-type responses that are rapidly shut off during persistent stimulation. The green line shows the responses in cells in which the inhibitory signal indicated by (⊥) is bypassed by RasCQ62L.

Our results provide new insights about the negative regulators in the chemotactic signaling pathways. Many G protein–coupled signaling events rapidly subside when cells are exposed to a step increase in chemoattractant. The time courses of RasC activation, PKB phosphorylation, and downstream chemotactic responses all reflect this rapid shutoff (Figs. 2 and 3). When the activation of RasC is prolonged, as in cells expressing the Q62L or G13V mutation, the kinetics of all of the downstream responses are similarly extended, suggesting that RasC inactivation is a rate-limiting step for the shutoff. Previous experiments of G protein signaling showed that α and βγ subunits of G protein remain dissociated (i.e., activated) as long as chemoattractant receptors are occupied (Janetopoulos et al., 2001). Together, these results argue that the site of shutoff lies between G proteins and the Ras regulators (Fig. 9).

Why does prolonged activation of RasC impair chemotaxis? Chemotaxis involves the interaction between spontaneous motility and directional sensing. In the absence of a chemoattractant gradient, actin-based membrane protrusions are formed along the cell perimeter, propelling the cell in random directions. In a gradient, directional sensing generates intracellular asymmetries that bias motility. Activation of Ras proteins and TORC2-mediated PKB phosphorylation have been shown to occur selectively at the leading edge of chemotaxing cells as well as at the tips of pseudopodia and are thus in a position to bias motility (Sasaki et al., 2004, 2007; Kamimura et al., 2008). We speculate that extending RasC activation interferes with chemotaxis in multiple ways. First, pseudopodia extension and retraction that underlie random migration as well as chemotaxis likely depend on the timely activation and inactivation of Ras proteins. Indeed, we have observed that both basal motility and responses to chemotactic stimuli are altered in cells expressing RasCQ62L. The character and distribution of pseudopods in cells expressing RasCQ62L appear to be different from those in wild-type cells (Fig. 3). Second, because the dispersion length of a protein is proportional to its half-life, the constitutively activated form of RasCQ62L is expected to have a broader spatial distribution than that of wild-type RasC. As RasCQ62L diffuses further before being inactivated, the downstream responses it controls will be delocalized as well, impairing cells’ ability to interpret the directional signal. Therefore, the rapid inactivation of RasC is critical for localizing downstream responses and directional sensing.

Our results provide the first substantial evidence that TORC2 is under the control of a Ras protein and open the possibility for further study of the regulatory mechanism of TORC2. Loss of function in RasC greatly reduces PKB phosphorylation (Fig. 1), and the effects of RasCQ62L on PKBR1 phosphorylation are suppressed by deleting PiaA (Fig. 4). These in vivo results indicate that the major effects of RasC on chemotaxis are mediated through TORC2 and PKBR1. The active form of RasC promotes TORC2-dependent phosphorylation of the two PKBs in vitro in the absence of any stimulus (Figs. 7 and 8). This reaction exhibits several characteristics that are consistent with a RasC–TORC2–PKB pathway. It is blocked by exogenous RBD and does not occur in lysates lacking the TORC2 component PiaA or Rip3 but can be rapidly initiated by adding Flag immunoprecipitate from piaA− cells expressing Flag-PiaA. Further experiments indicate that the reconstituting activity associated with the Flag immunoprecipitate likely contains a functional TOR complex (Fig. 8, B–D). Importantly, TORC2 binds specifically to RasCQ62L but not to inactivated wild-type RasC (Fig. 8 F), suggesting that a regulated interaction may contribute to the stimulation of TORC2 activity by RasCQ62L. Interestingly, we found that RasCQ62L lacking the C-terminal CAAX motif is not able to extend the kinetics of PKB phosphorylation (unpublished data), indicating that the membrane localization of RasC is critical for its in vivo function in activating TORC2.

A role for a Ras protein in PKB activation and cell migration may not seem surprising, as it has been shown that Ras proteins bind to both D. discoideum and mammalian PI3Ks (Rodriguez-Viciana et al., 1994; Pacold et al., 2000; Funamoto et al., 2002; Kae et al., 2004). However, our data show that the effects of RasCQ62L on chemotactic responses and the cytoskeletal activity are primarily mediated through TORC2. Furthermore, we found that disruption of PKBA but not PKBR1 in pten− cells suppresses its chemotaxis defects (unpublished data). Therefore, although expressing RasCQ62L and deleting PTEN both result in hyperstimulation of the PKB signaling, their effects appear to be mediated through different PKB isoforms. Our finding that TORC2 is a critical effector in Ras-mediated cell migration may serve as a stepping stone to understand cell motility in other organisms. PIP3-independent chemotaxis and chemoattractant-stimulated Ras activation have also been observed in human neutrophils (Worthen et al., 1994; Zheng et al., 1997). In many cancer cells that display altered cell migration, Ras proteins are found to be persistently activated (Oxford and Theodorescu, 2003). In addition, TORC2 has been suggested to regulate cytoskeletal-based events in various systems (Jacinto et al., 2004; Sarbassov et al., 2004; Kamada et al., 2005). It will be of great interest to learn whether the Ras–TORC2 pathway plays a similar role in the cytoskeleton organization and migration of these cells.

Materials and methods

Cell growth and differentiation

Cells were cultured axenically in HL5 medium at 22°C. Cells carrying expression constructs were maintained in HL5 medium containing 10–20 µg/ml G418 or 30–40 µg/ml hygromycin, or both as required. For differentiation, cells grown in HL5 were washed with development buffer (DB; 5 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4, and 0.2 mM CaCl2), starved in DB for 1 h at 2 × 107 cells/ml, and then pulsed with 50 nM cAMP every 6 min for 4.5 h. To induce the expression of Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L, doxycycline was added during the last 2 h of differentiation at a concentration of 40 µg/ml.

Gene disruption and plasmid construction

rasC− cells were constructed in an AX2 background. A disruption cassette, consisting of a genomic DNA fragment amplified by PCR using primers 5′-CATTCGATTGTATAATACACAACTAAATCA-3′ and 5′-GGGGTTGGATCATATTCAGCAATGAATTGA-3′, the Blasticidin S resistant (BSR) cassette from pLPBLP (Faix et al., 2004), followed by a genomic DNA fragment amplified by PCR using primers 5′-GAGCAAGGATGTTCTAATTGAATTGATTTC-3′ and 5′-GGGCATCAGCCAAATCTAGAGTAAACGTT-3′, was used to target the gene for deletion by homologous recombination. Knockouts were screened by PCR and confirmed by Southern blotting. Flag-RasC was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-AAATAAAAATGGATTATAAAGATGATGATGATAAATCAAAATTATTAAAATTAG-3′ and 5′-TTACAATATAATACATCCCCT-3′ from rasC cDNA plasmid. The resulting PCR fragment was cloned into the BglII site of pDM359 (Veltman et al., 2009) for doxycycline-inducible expression or the BglII site of pJK1 for constitutive expression. To create activated RasC, the conserved glycine at position 13 or glutamine at position 62 was mutated to valine or leucine, respectively, by quick change site-directed mutagenesis.

Immunoblotting

Differentiated cells were shaken at 200 rpm in DB with 5 mM caffeine for 20 min, washed with PM buffer (5 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM KH2PO4, and 2 mM MgSO4) twice, resuspended to 2 × 107 cells/ml in PM, and kept on ice before assay. Cells were stimulated with 1 µM cAMP, lysed in SDS sample buffer at various time points, and boiled for 5 min. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Kamimura et al., 2009). Antibodies recognizing specific phosphorylated sites were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti–phospho-PKB substrate antibody (rabbit monoclonal antibody) was used to detect the phosphorylation of the substrates of PKBA and PKBR1. Anti–phospho-PDK docking motif antibody (mouse monoclonal antibody) was used detect the phosphorylation of the HM of PKBR1. Anti–phospho-PKC (pan) antibody (rabbit monoclonal antibody) was used to detect the phosphorylation of the ALs of both PKBA and PKBR1. Monoclonal antibody from Sigma-Aldrich was used to detect the Flag tag. Anti–pan-Ras mouse monoclonal antibody from EMD was used to detect D. discoideum Ras proteins. Anti-T7 tag monoclonal antibody from EMD was used to detect the T7 tag.

In vitro PKB phosphorylation assay

For GTP-γS–stimulated PKB phosphorylation, cells were pretreated with caffeine as described in the previous section, resuspended in PM at a density of 8 × 107 cells/ml, and kept on ice before assay. 100 µl of cell suspension was mixed with equal volume of TM buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 2 mM MgSO4) in the presence or absence of 40 µM GTP-γS (Roche) and then immediately lysed through two layers of 5-µm filter membranes. Lysate samples were incubated on ice for 8–12 min before being stopped by the addition of SDS sample buffer. To test whether Ras proteins mediate the effects of GTP-γS, 10 µg GST-RBD or an equal amount of GST purified from bacteria was added together with GTP-γS.

To reconstitute PKB phosphorylation in vitro with lysates from wild-type cells and piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasCQ62L, 50 µl of cell suspension from each cell line was mixed together with 100 µl TM and 1 µl of 60 mM ATP and then filter lysed. Reactions were incubated on ice for 8–12 min and stopped by the addition of SDS sample buffer.

To make HSS, caffeine-treated cells were washed with PM twice, resuspended in glycerol lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor [Roche]) at a density of 8 × 107 cells/ml, and filter lysed. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 53,000 rpm in a TLA55 rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 4°C for 1 h, and the supernatant was collected. 100 µl of the supernatant was used in one reaction.

To prepare membrane fractions from piaA− cells expressing Flag-RasC or Flag-RasCQ62L, differentiated cells were resuspended in PM at a density of 8 × 107 cells/ml and filter lysed. Cell extracts were centrifuged at 16,000 g for 2 min. The membrane pellet was washed once with PM, resuspended with 100 µl PM, and used in one reaction.

To obtain Flag-PiaA immunocomplex used for experiments presented in Fig. 8 (B–E), Flag-PiaA was immunoprecipitated as follows: 20 µl anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with 1.2 ml HSS at 4°C for 3 h, washed with glycerol lysis buffer for three times and a total of 15 min, and then eluted with 100 µl of 500 ng/µl 3xFlag peptide (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C for 30 min. 100 µl of the eluate was used in one reaction. For experiments illustrated in Fig. 8 A, 200 ng/µl 3xFlag peptide was used to elute the complex. For PP242 treatment, the Flag-PiaA eluate was incubated with PP242 for 15 min on ice before 0.1 mM ATP and lysates from Flag-RasCQ62L/piaA− cells were added. The reaction was continued on ice for another 12 min before being stopped by the addition of SDS sample buffer.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay

rip3− cell was cotransformed with constructs expressing T7-Rip3 and Flag-RasC, or T7-Rip3 and Flag-RasCQ62L, or Flag-RasCQ62L only. Cells were differentiated, washed twice with PM, and lysed with immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor, 2 mM Na3VO4, and 0.3% CHAPS) for 10 min on ice. Cell extracts were centrifuged at 16,000 g for 2 min. Supernatant fraction was collected and incubated with 3 µl anti-T7 antibody at 4°C for 3 h. The immunocomplex was recovered by protein G–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) during a 1-h incubation at 4°C. Beads were washed four times with immunoprecipitation buffer, and proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in SDS sample buffer.

Micropipette assay and image acquisition

Differentiated cells were plated on coverslip chambers (NalgenNunc; LabTek) filled with DB and allowed to adhere to the surface for ∼15–20 min. A micropipette filled with 1 µM cAMP was placed into the field of view. Chemotaxis was recorded by time-lapse video using an inverted microscope (CKX41; Olympus) with a 20× NA 0.4 objective lens. Images were captured with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Motility speed was calculated as the total distance traveled by the cell divided by time. To calculate chemotactic index, the cosine of the angle between the direction of movement and the direction of chemoattractant gradient was determined for each frame. The values were weighted according to the length of the step and averaged. The distances between the start (d1) and the end (d2) point of the migration path to the needle were measured, and chemotactic motility was calculated as (d1 − d2) divided by the time the cell travels from the start to the end point. Persistency was calculated as the shortest linear distance between the start point and end point of the migration path divided by the total distance traveled by the cell.

1 µM cAMP was used to stimulate the translocation of LimEΔcoil-RFP. Cells were observed with a spinning disk confocal microscope (UltraVIEW DM16000; PerkinElmer) using a 40× NA 1.25-0.75 oil immersion objective. Images were captured with a cooled 12-bit charge-coupled device camera (LSI) and the Slidebook 4.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc.) and processed using Photoshop 7.0 and Illustrator 10.0 (Adobe). All experiments were performed at RT.

PH domain translocation assay

The assay was performed as described previously (Lilly and Devreotes, 1995). In brief, differentiated cells were treated with caffeine and resuspended in PM at a density of 8 × 107 cells/ml. At specific time points after stimulation with 1 µM cAMP, 100-µl aliquots of cells were filter lysed. Cell lysates were immediately mixed with equal volumes of supernatant containing PHcrac-GFP. Reactions were incubated on ice for 30 s before being stopped by the addition of 1 ml ice-cold PM. Membrane fractions were collected and blotted with anti-GFP antibody.

Actin polymerization assay

Cells were pretreated with 3 mM caffeine for 20 min, washed with PM, resuspended in PM plus 1 mM caffeine at a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml, and kept on ice before assay. Cells were warmed by shaking at RT for 10 min and then stimulated with 1 µM cAMP. At specific time points after stimulation, aliquots of cells were lysed by the addition of equal volumes of cold 2× assay buffer (2% Triton X-100, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM EGTA, 20 mM imidazole, and 0.1 mg/ml NaN3). Cell lysates were incubated at RT for 10 min with occasional agitation. The Triton-insoluble cytoskeletal fraction was collected by centrifugation at 8,000 g for 4 min, washed once with 1× assay buffer, dissolved in 2× SDS sample buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The amount of actin was determined by densitometric analysis of scanned Coomassie-stained gels.

ACA assay

Cells were grown to ∼5 × 106 cells/ml in HL5 medium and were allowed to differentiate to the chemotaxis competent stage by resuspending them in DB and providing exogenous pulses of 75 nM cAMP for 5.5 h. The cAMP receptor-mediated activation of ACA was performed as previously described (Kriebel and Parent, 2009). In brief, differentiated cells were treated with 2 mM caffeine for 30 min, washed and resuspended in ice-cold PM buffer, and stimulated with 10 µM cAMP at RT, except that the basal activity was measured on ice. Cells were withdrawn at the indicated time points into the reaction mix containing α-[32P]ATP diluted with unlabeled ATP to a final concentration of 100 nM. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 min and stopped with SDS/ATP, and the [32P]cAMP was purified by sequential Dowex AG 50W X-4 and alumina column chromatography.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that RasC but not RasG is required for the activation of the PKB pathway. Fig. S2 shows that constitutive expression of activated forms of RasC in rasC− cells results in prolonged activation of PKBR1 and defects in chemotaxis. Fig. S3 shows that PKBR1 and PKBA are required for ACA activation. Fig. S4 shows that RasC is activated in piaA− cells. Videos 1 and 2 show the translocation of LimEΔcoil-RFP in rasC− D. discoideum cells induced to express Flag-RasC or -RasCQ62L. Videos 3–10 show different lines of D. discoideum cells migrating in a gradient of cAMP generated by a micropipette. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201001129/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Xiong from Dr. P.A. Iglesias’ laboratory for help with chemotaxis video analysis, Dr. P. Van Haastert for providing the doxycycline-inducible expression vector, Dr. G. Weeks for the GST-RBD construct and RasC antibody, Dr. R.A. Firtel for the T7-Rip3 construct, Dr. R. Insall for the rasG− cell, M. Tang from the Devreotes laboratory for the piaA− cell, the D. discoideum cDNA project, and National BioResource Project for providing the RasC cDNA, and the proteomics core facility in Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine, for mass spectrometry analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants GM 28007 and GM 34933 to P.N. Devreotes and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. H. Cai is a recipient of Helen Hay Whitney postdoctoral fellowship.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ACA

- adenylyl cyclase

- AL

- activation loop

- DB

- development buffer

- HM

- hydrophobic motif

- HSS

- high-speed supernatant

- PDK

- phosphoinositide-dependent kinase

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- PI3K

- phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-trisphosphate

- RBD

- Ras-binding domain

- Tor

- target of rapamycin

References

- Cantley L.C. 2002. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 296:1655–1657 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.Y., Long Y., Devreotes P.N. 1997. A novel cytosolic regulator, Pianissimo, is required for chemoattractant receptor and G protein-mediated activation of the 12 transmembrane domain adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 11:3218–3231 10.1101/gad.11.23.3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faix J., Kreppel L., Shaulsky G., Schleicher M., Kimmel A.R. 2004. A rapid and efficient method to generate multiple gene disruptions in Dictyostelium discoideum using a single selectable marker and the Cre-loxP system. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:e143 10.1093/nar/gnh136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig L.A., Cooper G.M. 1988. Relationship among guanine nucleotide exchange, GTP hydrolysis, and transforming potential of mutated ras proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:2472–2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M.E., Apsel B., Uotila A., Loewith R., Knight Z.A., Ruggero D., Shokat K.M. 2009. Active-site inhibitors of mTOR target rapamycin-resistant outputs of mTORC1 and mTORC2. PLoS Biol. 7:e38 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca-Koh J., Kamimura Y., Devreotes P. 2006. Navigating signaling networks: chemotaxis in Dictyostelium discoideum. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16:333–338 10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias M.A., Thoreen C.C., Jaffe J.D., Schroder W., Sculley T., Carr S.A., Sabatini D.M. 2006. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr. Biol. 16:1865–1870 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funamoto S., Meili R., Lee S., Parry L., Firtel R.A. 2002. Spatial and temporal regulation of 3-phosphoinositides by PI 3-kinase and PTEN mediates chemotaxis. Cell. 109:611–623 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00755-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.E., Iijima M., Parent C.A., Funamoto S., Firtel R.A., Devreotes P. 2003. Receptor-mediated regulation of PI3Ks confines PI(3,4,5)P3 to the leading edge of chemotaxing cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:1913–1922 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Dibble C.C., Matsuzaki M., Manning B.D. 2008. The TSC1-TSC2 complex is required for proper activation of mTOR complex 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:4104–4115 10.1128/MCB.00289-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias P.A., Devreotes P.N. 2008. Navigating through models of chemotaxis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20:35–40 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M., Devreotes P. 2002. Tumor suppressor PTEN mediates sensing of chemoattractant gradients. Cell. 109:599–610 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00745-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E., Loewith R., Schmidt A., Lin S., Rüegg M.A., Hall A., Hall M.N. 2004. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:1122–1128 10.1038/ncb1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janetopoulos C., Jin T., Devreotes P. 2001. Receptor-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G-proteins in living cells. Science. 291:2408–2411 10.1126/science.1055835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kae H., Lim C.J., Spiegelman G.B., Weeks G. 2004. Chemoattractant-induced Ras activation during Dictyostelium aggregation. EMBO Rep. 5:602–606 10.1038/sj.embor.7400151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y., Fujioka Y., Suzuki N.N., Inagaki F., Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M.N., Ohsumi Y. 2005. Tor2 directly phosphorylates the AGC kinase Ypk2 to regulate actin polarization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:7239–7248 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7239-7248.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura Y., Devreotes P.N. 2010. Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase (PDK) activity regulates phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent and -independent protein kinase B activation and chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 285:7938–7946 10.1074/jbc.M109.089235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura Y., Xiong Y., Iglesias P.A., Hoeller O., Bolourani P., Devreotes P.N. 2008. PIP3-independent activation of TorC2 and PKB at the cell’s leading edge mediates chemotaxis. Curr. Biol. 18:1034–1043 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura Y., Tang M., Devreotes P. 2009. Assays for chemotaxis and chemoattractant-stimulated TorC2 activation and PKB substrate phosphorylation in Dictyostelium. Methods Mol. Biol. 571:255–270 10.1007/978-1-60761-198-1_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnoub A.E., Weinberg R.A. 2008. Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:517–531 10.1038/nrm2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J.S., Insall R.H. 2009. Chemotaxis: finding the way forward with Dictyostelium. Trends Cell Biol. 19:523–530 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel P.W., Parent C.A. 2009. Group migration and signal relay in Dictyostelium. Methods Mol. Biol. 571:111–124 10.1007/978-1-60761-198-1_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel P.W., Barr V.A., Parent C.A. 2003. Adenylyl cyclase localization regulates streaming during chemotaxis. Cell. 112:549–560 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00081-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Parent C.A., Insall R., Firtel R.A. 1999. A novel Ras-interacting protein required for chemotaxis and cyclic adenosine monophosphate signal relay in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell. 10:2829–2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Comer F.I., Sasaki A., McLeod I.X., Duong Y., Okumura K., Yates J.R., III, Parent C.A., Firtel R.A. 2005. TOR complex 2 integrates cell movement during chemotaxis and signal relay in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:4572–4583 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly P.J., Devreotes P.N. 1995. Chemoattractant and GTP gamma S-mediated stimulation of adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium requires translocation of CRAC to membranes. J. Cell Biol. 129:1659–1665 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C.J., Spiegelman G.B., Weeks G. 2001. RasC is required for optimal activation of adenylyl cyclase and Akt/PKB during aggregation. EMBO J. 20:4490–4499 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meili R., Ellsworth C., Lee S., Reddy T.B., Ma H., Firtel R.A. 1999. Chemoattractant-mediated transient activation and membrane localization of Akt/PKB is required for efficient chemotaxis to cAMP in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 18:2092–2105 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meili R., Ellsworth C., Firtel R.A. 2000. A novel Akt/PKB-related kinase is essential for morphogenesis in Dictyostelium. Curr. Biol. 10:708–717 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00536-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford G., Theodorescu D. 2003. Ras superfamily monomeric G proteins in carcinoma cell motility. Cancer Lett. 189:117–128 10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00510-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacold M.E., Suire S., Perisic O., Lara-Gonzalez S., Davis C.T., Walker E.H., Hawkins P.T., Stephens L., Eccleston J.F., Williams R.L. 2000. Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. Cell. 103:931–943 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00196-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C.A., Blacklock B.J., Froehlich W.M., Murphy D.B., Devreotes P.N. 1998. G protein signaling events are activated at the leading edge of chemotactic cells. Cell. 95:81–91 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81784-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Viciana P., Warne P.H., Dhand R., Vanhaesebroeck B., Gout I., Fry M.J., Waterfield M.D., Downward J. 1994. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase as a direct target of Ras. Nature. 370:527–532 10.1038/370527a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov D.D., Ali S.M., Kim D.H., Guertin D.A., Latek R.R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Sabatini D.M. 2004. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 14:1296–1302 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov D.D., Guertin D.A., Ali S.M., Sabatini D.M. 2005. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 307:1098–1101 10.1126/science.1106148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A.T., Chun C., Takeda K., Firtel R.A. 2004. Localized Ras signaling at the leading edge regulates PI3K, cell polarity, and directional cell movement. J. Cell Biol. 167:505–518 10.1083/jcb.200406177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A.T., Janetopoulos C., Lee S., Charest P.G., Takeda K., Sundheimer L.W., Meili R., Devreotes P.N., Firtel R.A. 2007. G protein–independent Ras/PI3K/F-actin circuit regulates basic cell motility. J. Cell Biol. 178:185–191 10.1083/jcb.200611138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider N., Weber I., Faix J., Prassler J., Müller-Taubenberger A., Köhler J., Burghardt E., Gerisch G., Marriott G. 2003. A Lim protein involved in the progression of cytokinesis and regulation of the mitotic spindle. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 56:130–139 10.1002/cm.10139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman D.M., Keizer-Gunnink I., Haastert P.J. 2009. An extrachromosomal, inducible expression system for Dictyostelium discoideum. Plasmid. 61:119–125 10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthen G.S., Avdi N., Buhl A.M., Suzuki N., Johnson G.L. 1994. FMLP activates Ras and Raf in human neutrophils. Potential role in activation of MAP kinase. J. Clin. Invest. 94:815–823 10.1172/JCI117401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z., Zhang N., Murphy D.B., Devreotes P.N. 1997. Dynamic distribution of chemoattractant receptors in living cells during chemotaxis and persistent stimulation. J. Cell Biol. 139:365–374 10.1083/jcb.139.2.365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Charest P.G., Firtel R.A. 2008. Spatiotemporal regulation of Ras activity provides directional sensing. Curr. Biol. 18:1587–1593 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Eckerdal J., Dimitrijevic I., Andersson T. 1997. Chemotactic peptide-induced activation of Ras in human neutrophils is associated with inhibition of p120-GAP activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272:23448–23454 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]