Abstract

Background

Studies have shown that a large portion of patient satisfaction is related to physician care, especially when the patient can identify the role of the physician on the team. Because patients encounter multiple physicians in teaching hospitals, it is often difficult to determine who the patient feels is his or her main caregiver. Surveys evaluating resident physicians would help to improve patient satisfaction but are not currently implemented at most medical institutions.

Intervention

We created a survey to judge patient satisfaction and to determine who patients believe is their “main physician” on the teaching service.

Methods

Patients on a medical teaching service at The Miriam Hospital during 20 days in March 2008 were asked to complete the survey. A physician involved in the research project administered the surveys. Surveys included 3 questions that judged patient's perception and identification of their primary physician and 7 questions regarding patient satisfaction. Completed surveys were analyzed using averages.

Results

Of the 126 patients identified for participation, 102 (81%) completed the survey. Most patients identified the intern (first-year resident) as their main physician. Overall, more than 90% of patients expressed satisfaction with their main physician.

Conclusion

Most patients on the teaching service perceived the intern as their main physician and were satisfied with their physician's care. One likely reason is that interns spend the greatest amount of time with patients on the teaching service.

Introduction

Over the last decade, hospitals and physicians have sought feedback from patients to improve care, specifically patients' satisfaction with their physician or physician team. Patient satisfaction is influenced by technical factors, interpersonal factors and attributes of the environment for care, and the extent to which care met patients' expectations.1,2 Studies of patient perceptions have found that physician teams' professionalism and communication skills are important to patient satisfaction,3–6 and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has focused on increasing residents' competence in professionalism and interpersonal and communication skills.7,8 Residents themselves believe that a focus on professionalism and communication is an important way to improve patient care and satisfaction.9 Studies in the ambulatory setting have shown that patients are generally satisfied with their medical care in resident clinics,10–13 with 2 studies finding that patient satisfaction was higher when care was provided by more advanced residents (residents in postgraduate years 2–4) than by interns (postgraduate year 1).10,12

Connecting resident empathy and patient satisfaction, Thomas Jefferson University developed a scale to gauge the physician-patient relationship's implications on patient satisfaction in an outpatient internal medicine clinic.15 A study conducted in an outpatient ophthalmology clinic showed that a simple handshake and introduction improved satisfaction,16 and another found that by decreasing waiting times and by spending more time with a patient, satisfaction was improved.17

Although a number of studies in the outpatient setting have assessed the variables that affect patient satisfaction, there are fewer studies related to inpatient care by resident physicians.3,4,10,14–17 Some of these have found that a significant portion of patient satisfaction is related to the physician team and that it is important for patients to identify the role of the physician on the team.4,11,14,15

A study that examined patient satisfaction in the teaching inpatient setting found that, although nursing care had the largest influence on patient satisfaction, the contribution of resident and faculty care to overall satisfaction is high.14 A classic review of theory and empirical work on patient satisfaction found that the attribute of providers and organizations most consistently associated with higher patient satisfaction is more “personal” care, including the ability to identify a personal provider responsible for care provision and coordination. Yet to date, there has been little research on patients' identification of a “main physician” when receiving care on a teaching service and which physicians patients most often will identify as their main physician. In internal medicine, it is common for a patient care team to comprise a medical student, an intern (postgraduate year 1), a resident (postgraduate year 2 or 3), and an attending physician who all care for the same patient along with nurses and other hospital staff. With so many providers, we believe that it may be important to patients to be able to identify the “lead” or “main” physician who makes diagnostic and therapeutic decisions on their behalf. Our study is the first to use a survey to assess who the patient perceives as the main physician on a teaching service, while also assessing patient satisfaction regarding the care by this physician.

Methods

After obtaining approval from the Lifespan Health System Institutional Review Board, the research team was made aware of all discharges or transfers from the teaching internal medicine services at The Miriam Hospital between March 1, 2008, and March 20, 2008. The research team was notified by the resident by phone, page, or verbal interaction when patients were discharged or transferred. Once notified, a researcher would collect demographic data on the patient through the medical chart and then would visit the patient to conduct a brief 2-part survey. To avoid interobserver variability 1 researcher conducted all of the chart reviews and administered the surveys to the patients. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to administering the survey. The survey was voluntary and anonymous (no identifying patient information was recorded).

In the first part of the survey, participants were asked 3 questions by the researcher: (1) Who do you think is your main physician?, (2) Who spends the most time with you?, and (3) To whom did you feel closest to during your hospital stay? To help identify members of the medical team, the researcher showed the patient photographs of the medical students, interns, and residents. The researcher also provided the names of attending and/or subspecialty physicians involved in the patient's care during the hospital stay. The patient or a family member recorded the patient's answers. For the second part of the survey, the researcher left the room and allowed the patient to answer yes/no questions about his or her main physician, along with additional comments if necessary. Family members helped in cases in which the patient was not able to complete the paper survey. Fourth-year medical students who functioned as subinterns were considered as interns for this analysis because of their internlike role on the team. The category “attending physicians” included hospitalists for patients who did not have a private physician with admitting privileges or a primary care physician. The survey took approximately 5 minutes to complete. Surveys were collected by a researcher and safeguarded until they were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis (frequencies and percentages) of all data obtained. The data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA).

Results

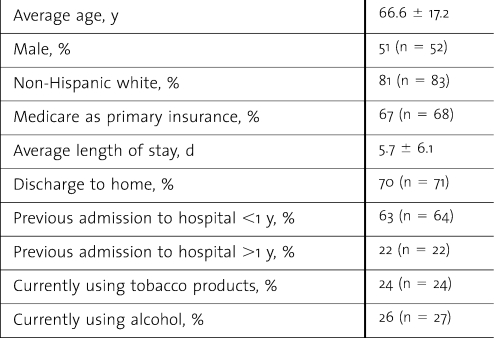

We identified 126 patients eligible to complete the survey. Excluded patients were those who declined to take the survey (7), did not speak English (4), had impaired mental status (6), were transferred to another service (3), or could not identify 1 physician as their main physician (4). Responses for the remaining 102 patients were included in the analysis. table 1 shows demographics for the patients included in the analysis. The average age of participants was 66 years; 51% were male and 67% had Medicare as their primary insurance. Seventy percent were discharged to home, and 30% were discharged to a nursing home or rehabilitation facility or transferred to another hospital. The mean length of stay was 5.7 ± 6.1 days.

Table 1.

Surveyed Patient Demographics

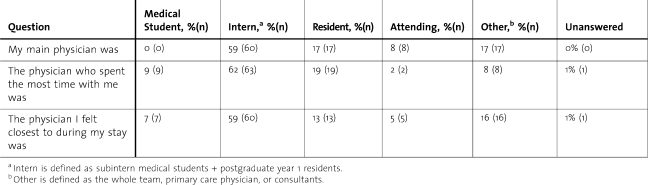

Patients identified their interns (and senior medical students functioning as subinterns) as their main physician 59% of the time. Sixty-two percent of patients stated the intern spent the most time with them, and 59% said they felt closest to the intern during their stay. The results of questions 1 to 3 are in table 2. Residents and “other” were recognized second most frequently, while attending physicians were rarely seen as the main physician on a teaching service. Other physicians identified as the main physician included outpatient primary care physicians who were not the attending of record, consultants who were involved in the patient's care, and proceduralists.

Table 2.

Survey Results for Questions 1 to 3

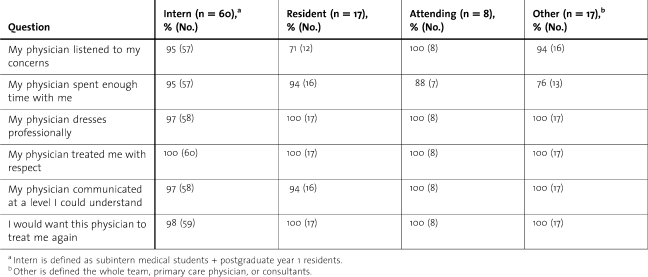

Greater than 90% of patients were satisfied with their main physician in all aspects of care (questions 4–9). The lowest scores were in response to questions 4 and 5, time spent with patients and listening to patients' concerns, which prior surveys have identified as being important variables in patient satisfaction. The percentage of patients reporting being satisfied in response to question 4 (“My physician listened to my concerns”) was lower (71%) for patients who identified the resident as their main physician than for those 95% who perceived the intern as their main physician. Physicians other than residents scored lower on the question about time spent with the patient. Complete results for questions 4 to 9 are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Question 4 to 9 Results (If participants identified a main physician in Question 1)

Question 10 of the survey provided space for the patients or family to provide any other comments regarding their physician(s) during the course of their stay. Comments included commendations and those that identified area for improvement. In their commendations, patients stated that physicians “…showed great concern for patients…,” “…gave me a straight answer…,” and “…were not above me.” Other comments included, “She listened,” and “The intern showed personal concern and communicated with my wife daily.” A common theme of praise included the team showing concern and keeping patients informed. In identifying areas for improvement, multiple respondents stated that physicians were “…in and out…,” “…did not spend enough time,” and “…did not answer all my concerns…”. These comments support the importance of communicating with patients and spending adequate time at the bedside.

Discussion

Our study showed a high level of patient satisfaction on an inpatient teaching service. Patients generally felt that they were well taken care of by physicians in training. Although overall satisfaction was high, hospitalized patients believed that improvement could be made if physicians spent more time with them. Patients on a medical teaching service have multiple interactions with multiple physicians each day. The intern on these teaching services often serves as the “point person” to coordinate the care of the patient and to deal with moment-to-moment issues. In most teaching hospitals, it is the intern who is expected to know the details about the care and social circumstances of the patient and who spends the most time with the patient. By documenting that most patients felt that the intern was the main physician and was the provider who spent the most time with the patient, our study reinforces the important role of physicians-in-training in patient care.

Our study has some limitations. First, the sample size is small and the study period was brief. Yet we believe the study period and population sampled is representative of the patients during a typical month on our medical teaching service. Second, our survey questions were not externally validated, and some patients may not have fully understood the meaning of the questions. Third, because photos were only shown of the residents and medical students, and the names were stated of all others involved with the patients' care, there may be a bias toward the identification of providers with photographs. We acknowledge that there is a potential bias when a survey is administered to still-hospitalized patients. However, we felt that we would have much higher accrual with this method, compared with the accrual from a survey sent to patients who had gone home. A potential bias also exists with resident coverage on weekends of patients in our hospital. During half of the weekends, patients were cross covered by the second- or third-year resident who was on one of the other service teams at the hospital. Pictures of any resident who covered the patients were shown to those patients being surveyed. Because there were few discharges on weekends and because the residents were the same during the whole month we felt the effect of cross coverage was minimal in this study.

Finally, the schedules of caregivers were not factored into the analysis. Because this survey followed the schedule of the residents for a month, it would be interesting to know if residents were preferentially identified as the main physician because their presence was more continuous (ie, Were attending physicians switching on and off service every few days but were the same residents present for many weeks in a row?).

Conclusions

Our study identified patients' perception of their main physician on a teaching service and assessed patient satisfaction in an inpatient setting. In most cases, patients perceived the intern as their main physician and identified him or her as spending the most time with them. Overall patient satisfaction with all providers identified as the main physician was high. In a teaching hospital, where interns play an important role in daily patient care, it is encouraging to know that patients feel that the interns are their main physicians.

Although overall patient satisfaction with most caregivers was high in our study, improvement efforts may be targeted to increasing the time physicians spend with patients. Because interns are considered the main physicians on the teaching service, program directors should place even greater emphasis on the teaching of communication and interpersonal skills to enhance residents' skills for communicating and interacting with patients and families. Residents also should be included in committees that address patient satisfaction and the environment for care, with the aim of targeting specific areas where patient satisfaction could be improved through the involvement of residents.

Future research should explore how patients quantify time spent with a physician and whether important predictors of patient satisfaction relate to the quality or the quantity of this interaction. Future research should also explore why some patients in our study could not identify a main physician. Future research should include studies in multiple types of teaching institutions to see if the results of our study are reproducible and generalizable.

Footnotes

All authors are at Brown University and Miriam Hospital. Samir Dalia, MD, is third-year resident in Internal Medicine; and Fred J. Schiffman, MD, is Professor in Medicine and Co-Associate Program Director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

The authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Ms Sandra Coletta who is the current CEO of Kent County Hospital in Rhode Island and the former COO of The Miriam Hospital for her input and help with the study design.

Editor's Note: The online version (164KB, doc) of this article includes the survey questions.

References

- 1.Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell S. M., Roland M. O., Buetow S. A. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1611–1625. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancy W., Macpherson D., Hanusa B., et al. Patient satisfaction in resident and attending ambulatory care clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.91005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malcolm C. E., Wong K. K., Elwood-Martin R. Patients' perceptions and experiences of family medicine residents in the office. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(4) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castillo L., Dougnac A., Vincent I., Munoz V., Rojas V. The predictors of satisfaction of patients in a university hospital. Med J Chile. 2007;135(6):696–701. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872007000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiggins M., Coker K., Hicks E. Patient perceptions of professionalism: implications for residency education. Med Educ. 2009;43(1):28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swing S. R. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):648–654. doi: 10.1080/01421590701392903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swing S. R., Schneider S., Bizovi K., et al. Using patient care quality measures to assess educational outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(5):463–473. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Symons A., Swanson A., McGuigan D. A tool for self-assessment of communication skills and professionalism in residents. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monk S., Nanagas M. T., Fitch J. L., Stolfi A., Pickoff A. S. Comparison of resident and faculty patient satisfaction surveys in a pediatric ambulatory clinic. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18(4):343–347. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1804_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santen S., Hemphill R., Prough E., et al. Do patients understand their physician's level of training?: a survey of emergency department patients. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):139–143. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz-Moral R., Pérula de Torres L. A., Jaramillo-Martin I. The effect of patients' met expectations on consultation outcomes: a study with family medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):86–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0113-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quintana J., Gonzalez N., Bilbao A., et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with hospital health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:102. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnick A. S., Disbot M., Wurster A., Mullen J. L., Kaiser L. R., Morris J. B. Contributions of surgical residents to patient satisfaction: impact of residents beyond clinical care. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(3):243–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser K., Markham F. W., Adler H. M., McManus P. R., Hojat M. Relationships between scores on the Jefferson scale of physician empathy, patient perceptions of physician empathy, and humanistic approaches to patient care: a validity study. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(7):CR291–CR294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis R., Wiggins M. N., Mercado C. C., O'Sullivan P. S. Defining the core competency of professionalism based on the patient's perception. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35(1):51–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feddock C., Hoellein A., Griffith C., et al. Can physicians improve patient satisfaction with long wait times? Eval Health Prof. 2005;28(1):40–52. doi: 10.1177/0163278704273084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]