Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is major global health problem. In China, where about 120,000,000 persons are chronically infected, CHB has been treated for centuries with traditional Chinese medicines (TCM). The aim of this review was to summarize and meta-analyze critically the results of randomized, controlled, clinical trials (RCTs) of TCM formulations reported from China in 1998--2008 for treatment of CHB. RCTs comparing either TCM formulations alone or in combination with interferon or lamivudine (IFN/LAM) versus IFN or LAM were included. The Chinese electronic databases were searched. The methodological quality of RCTs was assessed by the Jadad-scale. Results: (i) TCM had a greater beneficial effect (p = 0.0003) than IFN and slightly better effect (p = 0.01) than LAM on normalization of serum ALT. (ii) TCM had a similar beneficial effect when compared with IFN or LAM for CHB on antiviral activity as evidenced by the loss of serum HBeAg and HBV DNA. (iii) TCM enhanced IFN and LAM anti-viral activities and improvements of liver function. Quality of many studies was poor; often, reports lacked information regarding methods of randomization or blinding, and adverse events. In conclusion, some TCM seem effective as alternative remedies for patients with CHB suggesting that further study of TCM in the treatment of CHB is warranted, both in pre-clinical models of HBV infection and in higher quality RCTs world-wide.

Keywords: Chinese medicine, hepatitis B, clinical trials, interferon, lamivudine liver disease natural products, statistical analysis

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a major global health problem. Worldwide, more than two billion people have been infected the hepatitis B virus (HBV), and approximately 400 million people are chronic carriers of the virus. Chronic infection with HBV can significantly impair the quality of life and life expectancy of patients because of the potential for disease progression, which can lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. It is estimated that worldwide more than 600,000 individuals die from HBV-related liver disease each year 1. In China alone, there are at least 120,000,000 individuals carrying HBV 2.

Traditional Chinese Medicines and Liver Diseases in China

The ‘Yellow Emperor’s Internal Classic’, an ancient book containing records of traditional Chinese medicines (TCM), indicates that TCM have been used to treat chronic liver disease in China at least since 475 BCE. Today, TCM are still used extensively for the treatment of CHB in China. Thousands of different herbs have been used in numerous TCM formulations (mixtures of different herbs) for the treatment of CHB. These TCM formulations are based on the collective wisdom of Chinese clinicians and practitioners, coupled with centuries of accumulated experience working with these herbs.

The general philosophical underpinning of Chinese medicine and use of TCM is that of ‘holistic medicine’. Thus clinicians in China pride themselves on treating the person as a whole, including body, mind, and spirit. TCM formulations are typically selected based upon the purported individual properties of the herbs, and their abilities to work in complementary fashion with other herbs in the mixture. For example, a wide-spread strategy underlying TCM treatment of CHB is to: (i) relieve anxiety and symptoms and improve the quality of life of the patients; (ii) alleviate inflammation; (iii) arrest hepatic fibrosis; (iv) improve immune function; and (v) improve lipid metabolism. Somewhat analogous is the recent recommendation of the “polypill” to manage cardiovascular disorders and risk factors3.

Standard Modern Medical Treatments for CHB

Currently, the approved remedies worldwide for patients with CHB are interferon (IFN) and lamivudine (LAM) or other nucleoside analogues (e.g. adefovir, entecavir, tenofovir) 4. However, the overall therapeutic efficacy of IFN is limited by its inconvenient parenteral route of administration, unpleasant side effects, and expense. Although patients treated with lamivudine or other nucleoside analogues generally respond well to the medication and experience fewer side effects, in many cases the HBV replication increases markedly as soon as the treatment is stopped. Furthermore, the emergence of drug resistance and viral variation limit their efficacy as therapeutic agents for CHB, and the newer nucleoside analogues are prohibitively expensive for many patients. Thus, currently, in mainland China, IFN and LAM are the most commonly used Western remedies.

Goals of the Review

Despite the availability of IFN and/or nucleoside analogues, almost 80% of the patients with CHB in China rely on TCM therapy. In recent decades, a number of clinical trials have been performed in China to assess the therapeutic efficacy and safety of TCM for treating CHB infection. Studies have assessed the effects of TCM on CHB, both alone, and in combination with medicines of western origin. Results from the trials suggest that some TCM may indeed be effective therapeutic agents for the treatment of CHB. These encouraging findings have prompted investigations in both Asian and western countries to explore the potential of TCM in the treatment of liver diseases.

The goals of this review are to summarize and analyze results of recent RCTs employing TCM in the treatment of CHB. Furthermore, a search was performed to determine which individual herbs are used most frequently in TCM formulations, and which appear to have the greatest efficacy in treating CHB. This information may be used to begin to determine which herbs or combinations of herbs possess the most therapeutic potential for treatment of CHB. A portion of this review has appeared in abstract form (available on line at http://www.isvhld2009.org/secondary.php?section=Abstracts) and was presented at the 13th International Symposium on Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease, March 22, 2009, Washington, DC [oral presentation 92].

Data Bases Searched and Search Criteria

Searches of publications in the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and in PubMed were performed. Both searches were limited to trials reported between Jan., 1998 and June, 2008. The search key words used were combinations of TCM, herbs, single herb, herbal extract, plant and hepatitis B. All publications, which were written in either Chinese or English, were downloaded, read and critically reviewed.

Clinical trials studied included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled clinical trials (non-RCTs), and summaries of clinical experience. The diagnostic criteria for CHB were positivity for serum HBsAg and/or HBeAg for more than six months, with elevated levels of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Studies were selected for analysis if they named the individual herbs in the TCM formulation, and if there was an objective outcome measure (normalization in serum ALT, loss of serum HBeAg, and/or clearance of serum HBV DNA). If the studies matched the criteria outlined above, the names of the herbs were input into a database. The number of times individual herbs were used in different TCM formulations was recorded to determine the frequency with which particular herbs were used in TCM formulations used to treat CHB.

For assessing the effectiveness of TCM formulations in the treatment of CHB, the effects of TCM on CHB were compared to the effects of IFN and LAM on CHB. Use of IFN required therapy at a dose of at least 3 million units, administered three times a week for at least three months. Because of the existence of different forms of IFN, we included studies in which not only IFN α, but also IFN α-1b, IFN α -2b, or IFN α -2a were used. Use of LAM required its administration at a dose of at least 100 mg, administered once daily for at least thirty consecutive days. The review summarizes not only the effects of TCM on CHB, but also any reported side effects associated with therapy.

Due to the length limitations of this review, studies that assessed single herbs, or single herbal extracts in the treatment of CHB are not included. Although we used single herb and herbal extract as one of our search terms, these were used mainly to determine the total number of publications related to TCM and CHB that have been published in the past decade. We plan to write a review regarding the effects of single herbs as well as single herbal extracts in the treatment of CHB at a later date.

RCTs in humans were included, regardless of whether they were single blind, double blind or not blinded, which compared the therapeutic efficacy of (i) TCM formulations only versus IFN or LAM or (ii) TCM formulations plus IFN or LAM versus IFN or LAM on CHB. We focused on comparing the results of the virological response (loss of serum HBeAg and/or clearance of serum HBV DNA) and normalization of serum ALT levels at the end of treatment among the groups under comparison.

Methodological Quality and Statistical Analysis of RCTs

The methodological quality of the RCTs included in our study was assessed by the method of Jadad 5. The scores range from one to five, one or two being considered as low quality trials, and three to five as high quality. The Review Manager statistical software package (version 4.2, Biostat, Englewood, NJ) was used for the statistical analysis. According to usual standards for fitting to random-effects model [i.e., when the p value of heterogeneity of the results between two group trials is less than 0.1, or even when the p value is greater than 0.1, but the I2 parameters between two groups is greater than 50 ~ 70%], we chose the random-effects model to perform data analysis. Dichotomous data were presented as odds ratios (OR) and continuous outcomes as weighted mean differences, both with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

General Summary of Results

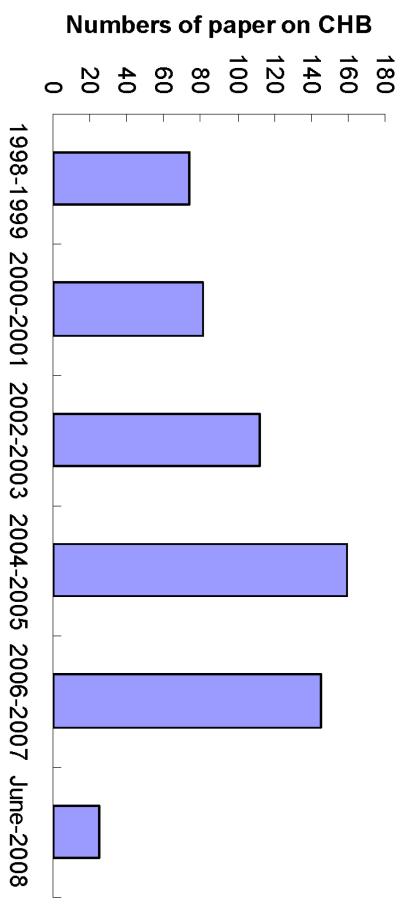

A total of 643 papers that fitted our criteria for inclusion were retrieved from CNKI and PubMed. 596 of the papers were in Chinese, and 47 were in English. Of these 643 papers, 487 were clinical trials, 80 were pre-clinical experimental studies and 76 were summaries of non-randomized clinical experience. Of 487 clinical trials, 356 were RCTs and 131 were non-RCTs. Of the 643 papers published between Jan 1998 to Jun 2008, the majority, (over 92%) were retrieved from CNKI (Fig. 1). For reasons unknown, the number of papers from China related to TCM use in the treatment of CHB has decreased in recent years (from 2006 to July, 2008; see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Numbers of publications reporting studies of TCM on HBV in China knowledge infrastructure from Jan., 1998 to June, 2008.

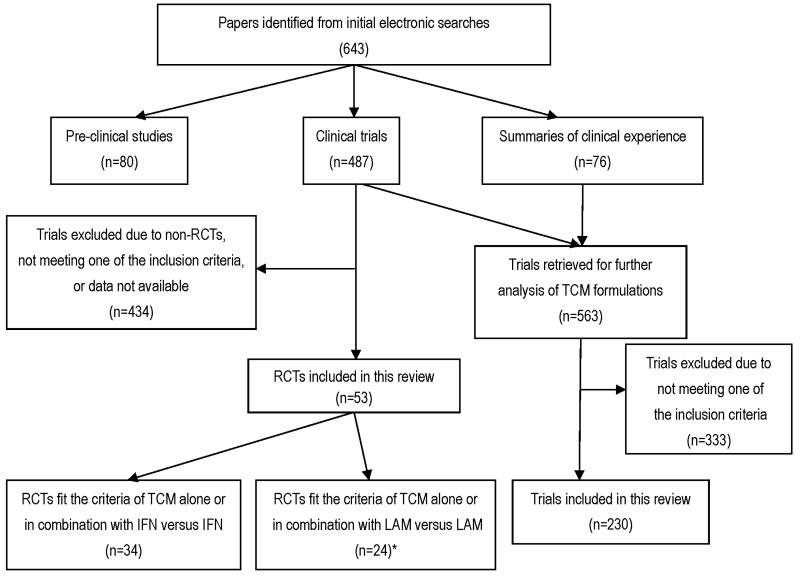

Of the 487 clinical trials, 434 were excluded because they were not RCTs or otherwise did not meet our inclusion criteria, or requisite data were not available. Thus, 53 RCTs were identified that reported random allocation of patients with CHB to treatment with TCM formulations (thereby meeting our inclusion criteria). Figure 2 provides a summary of studies reviewed and included or excluded from analysis. As regards assessment of the TCM employed in this published work, 76 publications described clinical experiences but did not describe clinical trials, whereas 563 described clinical trials. However, 333 of these were also excluded for one or more of the reasons given above. Thus, results of 230 trials were used to describe the TCMs used. Fifty three RCTs were analyzed to determine the effectiveness of TCM on CHB. The compositions of traditional medicines in each formulation of TCM were different among RCTs, but approximately 50 ~ 60% of the herbs were the same across different formulations. Details of these herbs and relevant references are provided in the supplementary material, available on-line at [to be inserted by Hepatology editor].

Fig. 2.

Summary of studies reviewed and those selected for or excluded from this meta-analysis.

Of the 53 RCTs included in our analysis, none reported the methods used for achieving prospective random allocation to treatment groups, allocation concealment, nor if they were double-blind, single-blind, or unblinded. Sixteen (27%) of the 53 RCTs had Jadad scores of three, and the remaining 37 (73%) had scores of two. Only 13 trials reported long-term follow up results, therefore we did not include data on long-term effects of TCM in this review.

Forty-eight of the 53 RCTs used clearance of HBV DNA as a measurement of effectiveness for treating CHB. PCR methods were used to measure HBV DNA in 23 RCTs (lower limit of detection = 1.0 × 103 copies/mL); spot hybridization methods were used in 2 RCTs (lower limit of detection not reported); in the remaining 23 RCTs, the methods used for HBV DNA measurement were not reported.

Twenty of the 53 trials reported whether or not patients experienced adverse events when taking TCM formulations. Of these 20 trials, 13 RCTs compared TCM with IFN, whereas 7 RCTs compared TCM with LAM. No serious adverse effects of TCM were reported. The majority of adverse events were reported by patients who received IFN during their treatment.

Compared with the number of clinical trials performed (487), the numbers of pre-clinical studies (which includes studies in animal and cell models) reporting the effects of TCM on CHB were much lower in number (80). This paucity of pre-clinical studies may be related in part to the difficulty in identifying the individual herbs in TCM formulations, coupled with the traditional and widespread belief that TCM have a long history of use, and are therefore safe. Furthermore, a lack of infrastructure and/or funding for preclinical research in China may have contributed to the dearth of pre-clinical studies undertaken.

Analysis of TCM Formulations

Of 487 clinical trials and 76 summaries of clinical experience, 230 trials met our criteria for inclusion in our analysis of the TCM formulations (Fig. 2). A goal of this analysis was to determine which particular herbs were used most frequently. A total of 203 different kinds of herbs were included in 230 TCM formulations for treatment of CHB. In Table 1, we list the 30 herbs that were included most frequently in the 230 TCM formulations (the references associated with Table 1 are listed in Suppl. Ref.1). For example, the herb used most often, Mongolian milkvetch root (Huang Qi), was used 143 times in 230 different formulations; the herbs used least frequently, Radix polygoni multiflori (He Shou Wu), and Herba scutellariae (Ban Zhi Lian), were used in only 23 of 230 formulations. Among the 230 formulations we reviewed, each formulation contained an average of 9 ingredients (range: 3-18).

Table 1.

The thirty herbs used most often for CHB in recent reports from China

| English herbal name (Chinese pinyin) | Frequency of use in 230 formulas |

Total numbers of patients given the herb in these reports |

|---|---|---|

| Astragalus (Huang Qi) | 143 | 12674 |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza (Dan Shen) | 135 | 10784 |

| Largehead atractylodes rhizome (Bai Shu) | 113 | 8304 |

| Radix bupleuri (Chai Hu) | 108 | 9888 |

| Polygonum cuspidatum (Hu Zhang) | 102 | 8700 |

| Oldenlandia diffusa (Bai Hua She She Cao) |

92 | 9198 |

| Radix glycyrrhizae (Gan Cao) | 85 | 7219 |

| Herba artemisiae capillaries (Yin Chen) | 79 | 7545 |

| Radix paeoniae rubra (Chi Shao) | 71 | 5580 |

| Radix cureumae wenyujin (Yu Jin) | 64 | 6323 |

| Poria (Fuling) | 60 | 4528 |

| Radix paeoniae alba (Bai Shao) | 60 | 4040 |

| Radix angelicate sinensis (Dang Gui) | 56 | 4391 |

| Radix codonopsis (Dang Shen) | 46 | 3308 |

| Radix et rhizoma rhei (Da Huang) | 38 | 3719 |

| Radix isatidis (Ban Lan Gen) | 35 | 2554 |

| Fructus schisandrae chinensis (Wu Wei Zi) |

33 | 3096 |

| Lycium chinensis mill (Gou Qi Zi) | 32 | 3480 |

| Fructus ligustri lucidui (Nv Zhen Zi) | 32 | 3319 |

| Herba sedi sarmentosi (Chui Pen Cao) | 29 | 2365 |

| Radix sophorae flavescentis (Ku Shen) | 28 | 1697 |

| Hawkthorn (Shan Zha) | 28 | 2805 |

| Fructus gradeniae (Zhi Zi) | 26 | 2475 |

| Pericarpium citri reticulatae (Chen Pi) | 25 | 1959 |

| Semen coicis (Yi Yi Ren) | 25 | 2767 |

| Phyllanthus urinaris (Zhen Zhu Cao) | 24 | 2071 |

| Carapax trioycis (Bie Jia) | 24 | 1939 |

| Radix scutellariae baicalensis (Huang Qin) |

24 | 1952 |

| Herba scutellariae (Ban Zhi Lian) | 23 | 2239 |

| Radix polygoni multiflori (He Shou Wu) | 23 | 2313 |

Abbreviations: CHB, chronic hepatitis B.

References for Table 1 are listed in Suppl. Ref. 1

Summary of Effects of TCM on CHB Infection

(i) TCM +/−IFN versus IFN

Thirty-four RCTs (n = 3656) compared TCM formulations to IFN in the treatment of CHB. In 16 of these 34 trials, responses in patients receiving TCM only (n = 1918) were compared to those treated with IFN. (Selected demographics of subjects and design characteristics of included RCTs are summarized in Suppl. Table 1 and 2, and the associated references are listed in Suppl. References associated with Suppl. Tables). The average size of the trials was 120 patients (range: 47 to 248); the age at entry was 34.1 ± 2.8 (mean ± SD) years; the proportion of male patients was 63.7 ± 16.3%; the mean duration of treatment was 145 ± 72 days with range 90 - 360 days (Table 2). In 18 of the 35 trials, patients received TCM plus IFN (n = 1738) and results were compared to patients treated with IFN alone, (Selected demographics of subjects and design characteristics of included RCTs are summarized in Suppl. Table 2 and 3, and the associated references are listed in Suppl. References associated with Suppl. Tables). In these trials, the average number of subjects studied was 91, varying from 40 to 268; the mean age was 36.6 ± 2.8 years; the proportion of male patients was 70.3 ± 10.9%; the mean duration of treatment was 147 ± 85 days with range 60 - 360 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of 53 RCTs of TCM for CHB in China Jan., 1988 - June, 2008

| Variables | TCM alone vs IFN ( 16RCTs ) |

TCM+IFN vs IFN ( 18RCTs ) |

TCM alone vs LAM ( 6RCTs ) |

TCM+LAM vs LAM ( 14RCTs ) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 925 | 993 | 895 | 843 | 453 | 270 | 728 | 820 |

| Age (years) | 34.1±2.8 | 36.6±2.8 | 38.4±3.8 | 34.4±5.9 | ||||

| Gender (male %) | 63.7±16.3 | 70.3±10.9 | 54.0±6.3 | 65.4±13.0 | ||||

| Duration of treatment (days) |

145±71.9 90-360 |

147±85 60-360 |

150±67.1 30-180 |

313±155 90-720 |

||||

| Normalization of serum ALT (%) |

72.3±20.0 | 53.5±22.8 | 74.1±16.3 | 51.5±17.5 | 62.2±19.7 | 48.8±29.0 | 89.5±7.3 | 67.2±7.5 |

| OR (95%CI) | 2.42 [ 1.51 , 3.89 ] | 3.07 [ 2.35, 4.00 ] | 1.96 [ 1.15 , 3.32 ] | 3.40 [ 2.45, 4.70 ] | ||||

| Test of heterogeneity ( I 2 ) |

58.7% | 0% | 60.8% | 7.9% | ||||

| Overall effect P value |

0.0003 | < 0.00001 | 0.01 | < 0.00001 | ||||

| Loss of serum HBeAg (%) |

55.5±16.3 | 41.7±14.1 | 51.0±12.0 | 33.6±7.9 | 51.5±17.8 | 37.7±26.7 | 40.9±18.7 | 23.5±14.4 |

| OR (95%CI) | 1.60 [ 1.00, 2.54 ] | 2.17 [1.74 , 2.72] | 1.57 [ 0.60 , 4.12] | 2.54 [ 1.95 , 3.32 ] | ||||

| Test of heterogeneity ( I 2 ) |

76.3% | 0% | 86.6% | 0% | ||||

| Overall effect P value |

0.05 | < 0.00001 | 0.36 | < 0.00001 | ||||

| Clearance of serum HBV DNA (%) |

51.0±12.1 | 43.3±11.0 | 58.4±11.8 | 43.2±14.6 | 57.7±19.5 | 54.8±28.2 | 80.1±18.5 | 64.6±17.4 |

| OR (95%CI) | 1.31 [ 0.87, 1.98 ] | 2.05[ 1.59, 2.65 ] | 1.20 [ 0.61 , 2.36 ] | 3.20 [ 2.09 , 4.92 ] | ||||

| Test of heterogeneity ( I 2 ) |

63.6% | 26.0% | 76.3% | 48.6% | ||||

| Overall effect P value |

0.20 | < 0.00001 | 0.59 | < 0.00001 | ||||

Note: Data presented as Mean ± SD

(ii) TCM +/− LAM vs LAM

Twenty RCTs (n = 2271) comparing the effects on CHB of TCM formulations and LAM were identified. In 6 of the 20 trials, patients received TCM only (n = 723), and their responses were compared to those of patients receiving LAM alone. (Selected demographics of subjects and design characteristics of included RCTs are summarized in Suppl. Table 4; the associated references are listed in Suppl. References associated with Suppl. Tables). The average size of these trials was 120 patients, varying from 60 to 328; the mean age was 38.4 ± 3.8 years; the proportion of male patients was 54.0 ± 6.3%; the mean duration of treatment was 150 ± 67.1 with range 30 - 180 days (Table 2). In 14 of the 20 trials, patients received TCM plus LAM (n = 1548) and patient responses were compared to those given LAM only. (Selected demographics of subjects and design characteristics of included RCTs are summarized in Suppl. Table 4 and 5, the associated references are listed in Suppl. References associated with Suppl. Tables.) The average size of these trials was 110 subjects, varying from 40 to 212; the mean age was 34.4 ± 5.9 years; the proportion of male patients was 65.4 ± 13.0%; the mean duration of treatment was 313 ± 155 days, with range 90 - 720 days (Table 2).

Meta Analysis of Data

We performed a meta-analysis of all the results from the 53 included RCTs, yielding a total of 12 comparisons (Suppl. Analyses 1 to 12). These results are summarized in brief in Table 2.

(i) TCM versus IFN treatment

Compared with IFN treatment alone TCM formulations had a significantly better effect on normalizing serum ALT, (OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.51 - 3.89, p = 0.0003), and were equivalent in reducing serum HBeAg (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.00 - 2.54, p = 0.07) and clearing serum HBV DNA (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.87 - 1.98, p = 0.20).

(ii) TCM plus IFN versus IFN treatment alone

Compared with IFN treatment alone, a combination of TCM formulations plus IFN showed a significant effect on reduction of serum HBeAg (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.74 - 2.72, p < 0.00001), improved clearance of serum HBV DNA (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.59 - 2.65, p < 0.00001), and improved normalization of serum ALT (OR 3.07, 95% CI 2.35 - 4.00, p < 0.00001).

(iii) TCM versus LAM treatment

Compared with LAM treatment alone (Table 2), TCM formulations showed no significant difference in reducing serum HBeAg (OR 1.57, 95% CI 0.60 - 4.12, p = 0.36) or clearance of serum HBV DNA (OR 1.20, 95% CI 0.61 - 2.36, p = 0.59). For serum ALT normalization (Table 2), TCM formulations were more effective than LAM (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.15 - 3.32, p = 0.01).

(iv) TCM plus LAM versus LAM treatment

Compared with LAM treatment alone (Table 2), the combination of TCM plus LAM showed a highly significant effect on reduction of serum HBeAg (OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.95 - 3.32, p < 0.00001), clearance of serum HBV DNA (OR 3.20, 95% CI 2.09 - 4.92, p < 0.00001) and normalization of serum ALT (OR 3.40, 95% CI 2.45 - 4.70, p < 0.00001).

We also performed similar analyses on the 16 RCTs of higher technical quality (Jadad score =3). The direction and pattern of the results were similar, although, as might be anticipated from a meta-analysis involving a smaller number of total subjects (n=731), the significance of effects was smaller and the CI’s were larger.

Herbs found in TCM Formulations Showing Promise for Treatment of CHB

Based on our review of the literature, we documented and ranked the top thirty individual Chinese herbs that were used in TCM formulations for the treatment of CHB patients in China (Table 1). Because the majority of herbs were administered in combination with other herbs in TCM formulations, it is not possible to determine exactly which individual herbs in the formulation have the greatest therapeutic potential in the treatment of CHB. However, based upon our review of all the papers included in our literature searches and upon the prior knowledge and experience of Drs. Zhang and Li, we have selected four herbs that seem worthy of additional, in-depth study. Below is a brief commentary on these 4 herbs.

Astragalus (Huang Qi)

The leguminous plant Astragalus (Fig. 3A), which is the herb most frequently used in TCM formulations for CHB (Table 1), has received a lot of attention by Chinese physicians because of its purported immune-modulating and anti-viral properties. Its principal ingredients include astragalosides and astragals polysaccharides, of which the latter has received particular attention for treatment of CHB.

Fig. 3.

Four typical herbs used in TCM for anti-HBV activity. A: Astragalus (Huang Qi), a leguminous plant; B: Polygonum cuspidatum (Hu Zhang) belonging to the plant genus polygonaceae; C: Radix et rhizoma rhei (Da Huang) also belonging to the plant genus polygonaceae; D: Phyllanthus urinaris (Ye Xian Zhu) belonging to the plant of the genus Phyllanthus urinaris. Note: The processed herb (Yin pian) is shown in the small picture.

In 2003, Zou et al 6 described anti-HBV activity of astragulus extracts in vitro. Previously, Huang et al 7 reported that the extract of astragalus inhibited HBV reverse transcriptase (HBV-RT) and deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase (DNA-DNAP) in a duck model of HBV. A more recent in vitro study indicated that astragalus strongly inhibits the secretion of HBsAg and HBeAg in the HepG 2.2.15 cell line8.

In 1995, a clinical RCT reported by Zhang et al 9 demonstrated that CHB patients treated with astragalus polysaccharides showed improved normalization of serum ALT, reduced serum HBeAg and clearance of serum HBV DNA when compared to control patients. It was also noted that astragalus polysaccharides alone induced an increase in endogenous IFN levels in vivo.

Polygonum cuspidatum ( Hu Zhang )

Polygonum cuspidatum (Fig. 3B), which is ranked in the top five of individual herbs used most frequently in TCM formulations for CHB (Table 1), belongs to the plant genus polygonaceae. Polydatin, the major active component in polygonum cuspidatum, is the most common herbal medicine used to treat patients with liver diseases in China 10, 11. Huang et al reported that Polygonum cuspidatum and one of its known active ingredients (resveratrol) strongly suppressed lipid peroxidation and protected rat hepatocytes injured by CCL4 in vitro 12. Studies by Zhou et al determined that resveratrol was effective in inhibiting HBV in HepG2.2.15 cells, perhaps by inhibiting HBV replication, and by inducing apoptosis 13. There are, however, no clinical trials in the literature related to the use of the individual herb Polygonum cuspidatum in treatment of CHB. Resveratrol is also found in other plants, including the skin of red grapes. The beneficial health effects of drinking red wine have been ascribed to resveratrol. A recent review documents growing evidence that resveratrol can prevent or delay the onset of a number of cancers, heart diseases, chemical and ischemic - induced injuries, inflammation and viral infections 14. Furthermore, Gedik et al reported that resveratrol reduces oxidative stress and histological alterations induced by liver ischemia/reperfusion 15.

Radix et rhizoma rhei (Da Huang)

Radix et rhizoma rhei (Fig. 3C) also belongs to the plant genus polygonaceae. It ranks number 15 of the top 30 herbs (Table 1) used in TCM formulations to treat CHB. Emodin is one of the major active compounds of Radix. In 2007, Dang et al showed that emodin had time-and concentration-dependent inhibitory effects on HBV in vitro 16. As early as 1997, Huang et al 15 reported that Radix extract significantly inhibited hepatic B virus reverse transcriptase (HBV-RT) and deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase (DNA-DNAP) in a duck HBV-model. In recent years, studies from both Liu and Li demonstrated that ethanol extracts of Radix can markedly inhibit the secretion of HBsAg and HBeAg in HepG2.2.15 cells 17, 18. Moreover, Li’s studies suggest that the compound anthraquinone chrysophanol 8-O-β-D-glucoside is the major active compound in Radix extract, and that this could be a promising candidate as a new anti-HBV drug.

Phyllanthus urinaris (Ye Xian Zhu)

The plant of the genus Phyllanthus urinaris (Fig. 3D) is a highly valued Chinese herb that has been used in TCM formulations to treat chronic liver disease for centuries. Phyllanthus belongs to the family euphorbiaceae, which has many members. Its high cost may limit its use by Chinese physicians in TCM formulations, which could explain why it is number 26 on the list of most frequent herbs in TCM for CHB (Table 1). However, phyllanthus is one of the herbs generally acknowledged in China to be of greatest value for treatment of CHB. A number of classes of compounds, including alkaloids and flavonoids, have been isolated and characterized from phyllanthus. In 1997, M. Ott et al 19 reported that the phyllanthus amarus plant suppressed HBV mRNA transcription in Huh-7 cell lines. In recent years, Eun et al 20 demonstrated that ellagic acid, a flavonoid isolated and purified from phyllanthus, could block the immune tolerance caused by HBeAg in HbeAg-producing transgenic mice. As described above, a number of RCTs looking at the therapeutic effectiveness of phyllanthus in the treatment of CHB have been performed. A systematic review of phyllanthus for CHB virus infection, performed in 2001 by J. Liu 21, concluded that phyllanthus species may have positive effects on antiviral activity and liver biochemistry in chronic HBV infection, and that further trials are warranted.

Discussion

Summary of Effectiveness of TCM in Treating CHB

To summarize, our review of the recent Chinese literature revealed that some TCM may have beneficial therapeutic effects on CHB. Our meta-analysis (Table 2) suggests that in patients with CHB (i), TCM have a similar curative effect as IFN/LAM on antiviral activity as evidenced by the loss of serum HBeAg and HBV DNA; (ii) TCM have a better effect on normalization of serum ALT; and (iii) TCM enhance IFN and LAM anti-virus activity and improvement of liver function. Of note is that there were no reported serious adverse events associated with the combinations of TCM studied. As used in China, these formulations seem to be very well tolerated, although many reports did not include data on adverse effects of therapy. Taken together, these results suggest that further study of TCM in the treatment of CHB is warranted.

It must be acknowledged, however, that the methodological quality of the trials evaluating the effect of TCM on CHB was generally not high: 37/53 (70%) of the RCTs included in this review were scored as having mediocre methodological quality [Jadad scores = 2]. No trial was identified as a multi-center, large-scale, prospective, double-blinded, controlled randomized trial. Furthermore, only 13 of the 53 RCTs performed long-term follow up studies. Nevertheless, when we repeated our analysis on the effectiveness of TCM formulations on CHB using only those RCTs that scored at least 3 on the Jadad scale (n = 16 trials), the results were not significantly different from those of lower methodological quality.

The possibility of publication bias in the reporting of results of clinical trials is always of concern. It was certainly a concern to us when performing the meta-analyses in this review. Obviously, the purported effectiveness of TCM formulations on CHB could be exaggerated if only positive results were published. To try to assess whether there was major publication bias, funnel plots were done when 9 or more studies were available for analysis. These plots did not show appreciable asymmetry [See Supplemental Meta-analyses 1-9], suggesting that there was not major publication bias. However, we emphasize the importance that investigators submit, and that journal editors publish, the results of negative, as well as of positive, clinical trials.

Summary

Traditional herbal medicines have been used in China for more than two thousand years, and they now are being used increasingly worldwide. The goal of this review was to summarize and analyze results of recent clinical trials utilizing TCM in the treatment CHB in China to help ascertain which herbs, or combination of herbs, possess the most therapeutic potential for treating CHB, and warrant further study. However, there are inherent difficulties associated with this type of analysis that are related to differences in philosophy in Chinese and Western Medicine.

Although therapeutics historically have been based upon observation and retrospective analyses, both in the occident and the orient, during the past 50 years, the study and approval of new ethical drugs, especially in western countries, has required persuasive data on efficacy and acceptable risks of toxicity. Such data generally are obtained from prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, large registration trials. The results of such studies notwithstanding, millions of people in the occident continue to use herbal products and dietary supplements, including those with chronic viral hepatitis 22 and other liver diseases. Thus, the actual practices of persons in China and the west are not so very different, despite the great cultural divides. Use of TCM in China is based on clinical observations and wisdom accumulated over centuries of use and practice. A difficulty in interpretation is that, typically, numerous herbs are used in combination in TCM formulations to attack a disease process in manifold ways. Each herbal product within the TCM formulations may have several different active ingredients. Furthermore, the content and biological activities of these ingredients can be influenced by many things, including where the herb was grown, and at what season it was harvested. Consequently, it is difficult to compare the results from TCM studies because different batches of the same TCM formulations could have somewhat different properties. This, in turn, makes it difficult, if not impossible, to apply western standards and analyses to studies of TCM. Nevertheless, the integration of TCM with modern technologies and therapies is a pre-requisite to further understanding the potential therapeutic benefits of TCM in the treatment of CHB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Nury Steuerwald and Hossein Sendi for helpful comments on this study. We thank Lin Zhang, Zhiyun He, and Leonora Kaufmann for their help with literature searches, study selection, and data extraction; Songhu Yang and Bing Ma for helping with statistical analyses; and Melanie McDermid for help with typing and submission of the manuscript.

Financial support came from a scholarship (to Lingyi Zhang) from the China Scholarship Council; a training award (to Lingyi Zhang) from the American College of Gastroenterology; The Fund for Liver, Digestive and Metabolic Disease Research of Carolinas Medical Center; and a grant (to Herbert L. Bonkovsky) from NIH (R01 DK 38825).

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- CHB

chronic hepatitis B

- CI

confidence intervals

- CNKI

China national knowledge infrastructure

- HBeAg

hepatitis B e antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- IFN

interferon

- LAM

lamivudine

- OR

odds ratios

- RCTs

randomized controlled trials

- TCM

traditional Chinese medicines

References

- 1.Rizzetto M, Ciancio A. Chronic HBV-related liver disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shan J. China has 120m hepatitis B carriers. China Daily. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNeil DG., Jr. Blood pressure is most lethal in poor and middle-income countries. The New York Times. 2008 May 6; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486–1500. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou YH, Yang Y, Wu Q. The effect of Huang Qi extract on anti-hepatitis B virus in vitro [In Chinese] Journal of Anhui Medical University. 2003;38:267–269. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang ZM, Yang XB, Gao WB, Shao XW, Chen HS. Inhibition of extracts of five Chinese traditional medicines on DHBV-RT-DNAP in vitro [In Chinese] Special Journal Pharmacy of People’s Mil Surg. 1997;13:71–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu XM, Yuan WS. In vitro study of the anti-HBV activity of astragalus [In Chinese] Guangdong Medical Journal. 2008;29:37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang FX, Sun DX, Li MX. Study on the preparation of astragals polysaccharides and the treatment in hepatitis [In Chinese] Journal of Pharmicol and Biologic Technology. 1995;2:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang Y, Zou HQ. Study on the effects of chemistry and pharmacology in Polygonum cuspidatum [In Chinese] Journal of Chinese Crude Drug. 1993;16:42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding XC, RUN BY, Wang Y. The treatment of neonate jaundice in 88 cases with the combination of traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine [In Chinese] National Medicine Forum. 2001;16:44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang ZS, Wang ZW, Liu MP. The protective effect of resveratrol on rat hepatocytes injured by CCL4 in vitro [In Chinese] Journal of Pharmacology China. 1998;14:543. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou X, Lu QJ, Wang L, Ye QN, Wen LQ, Zhang M. Inhibitory effect of resveratrol and its derivatives on HBV in vitro [In Chinese] China Pharmacology Journal. 2005;40:1904–1906. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankar S, Singh G, Srivastava RK. Chemoprevention by resveratrol: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front Biosci. 2007 Sep 1;12:4839–4854. doi: 10.2741/2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gedik E, Girgin S, Obay BD, Ozturk H, Buyukbayram H. Resveratrol attenuates oxidative stress and histological alterations induced by liver ischemia/reperfusion in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;46:7101–7106. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang SS, Zhang ZG, Zhang X, Song P, Bian J, Cheng YN. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus by emodin and astragalus polysaccharides in vitro [In Chinese] Journal of Xian Jiaotong University (Medical Sciences) 2007;28:521–525. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z, Li LJ, Sun Y, Li J. Identification of natural compounds with anti-hepatitis B virus activity from Rheum palmatum L. ethanol extract [In Chinese] Chemotherapy. 2007;53:320–326. doi: 10.1159/000107690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu N, Zhu BX, Huang ZC, Zhu YT, Chen QY, Guo XB, et al. The inhibitive effects of the ethanol extract from Radix et Rhizoma Rhei on the secretion of HBsAg and HBeAg [In Chinese] Journal of Chinese Crude Drug. 2004;27:419–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ott M, Thyagarajan SP, Gupta S. Phyllanthus amarus suppresses hepatitis B virus by interrupting interaction between HBV enhancer I and cellular transcription factors. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;27:908–915. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1997.2020749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang EH, Kown TY, Oh GT, Park WF, Park S-I, Park SK, et al. The flavonoid ellagic acid from a medicinal herb inhibits host immune tolerance induced by the hepatitis B virus-e antigen. Antiviral Research. 2006;72:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Lin H, Mcintosh H. Genus Phyllanthus for chronic hepatic B virus infection: a systematic review. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2001;8:358–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strader DB, Bacon R, Lindsay KL, La Brecque DR, Morgan T, Wright EC, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2391–2397. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.