Abstract

Three proteins from cyanobacteria (KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC) can reconstitute circadian oscillations in vitro. At least three molecular properties oscillate during this reaction, namely rhythmic phosphorylation of KaiC, ATP hydrolytic activity of KaiC, and assembly/disassembly of intermolecular complexes among KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC. We found that the intermolecular associations determine key dynamic properties of this in vitro oscillator. For example, mutations within KaiB that alter the rates of binding of KaiB to KaiC also predictably modulate the period of the oscillator. Moreover, we show that KaiA can bind stably to complexes of KaiB and hyperphosphorylated KaiC. Modeling simulations indicate that the function of this binding of KaiA to the KaiB•KaiC complex is to inactivate KaiA's activity, thereby promoting the dephosphorylation phase of the reaction. Therefore, we report here dynamics of interaction of KaiA and KaiB with KaiC that determine the period and amplitude of this in vitro oscillator.

Keywords: biological clocks, circadian rhythms, cyanobacteria, protein phosphorylation, modeling

Circadian rhythms are daily cycles of metabolic activity, gene expression, sleep/waking, and other biological processes that are regulated by self-sustained intracellular oscillators. A versatile system for the study of circadian oscillators has emerged from the study of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 (1). The circadian pacemaker in S. elongatus choreographs rhythmic patterns of global gene expression, chromosomal compaction, and the supercoiling status of DNA in vivo (2–4). Just three essential clock proteins from S. elongatus—KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC—can reconstitute a biochemical oscillator with circadian properties in vitro (5). This in vitro oscillator exhibits at least three rhythmic properties: phosphorylation status of KaiC (5), formation of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes (6, 7), and ATP hydrolytic activity (8). The relationship of the in vitro oscillator to the entire circadian system in vivo is not defined, but it is clear that the oscillator underlying the rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation is able to keep circadian time independently of transcription and translation processes in vivo and in vitro (5, 9), and therefore this posttranslational oscillator (PTO) may be necessary and sufficient as the core pacemaker for circadian rhythmicity in cyanobacteria (10).

The Kai proteins interact with each other to form complexes in which KaiC serves as the core component (6, 7, 11, 12). These complexes mediate the KaiC oscillation between hypophosphorylated and hyperphosphorylated forms in vivo and in vitro (5, 7, 9, 13–15). KaiC autophosphorylation is stimulated by KaiA, whereas KaiB antagonizes the effects of KaiA on KaiC autophosphorylation (13, 16). On the other hand, dephosphorylation of KaiC is inhibited by KaiA, and this effect of KaiA is also antagonized by KaiB (15). Therefore, KaiA both stimulates KaiC autophosphorylation and inhibits its dephosphorylation; KaiB antagonizes these actions of KaiA. In the in vitro system, Kai protein complexes assemble and disassemble dynamically over the KaiC phosphorylation cycle (6, 7). First, KaiA associates with hypophosphorylated KaiC, and KaiC autophosphorylation increases. Once KaiC is hyperphosphorylated, KaiB binds to the KaiC, and KaiC dephosphorylates within a KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex (7). When KaiC is completely hypophosphorylated, KaiB dissociates from KaiC and the cycle begins anew.

The 3D structures for KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC are known (10). The crystal structure of the KaiC hexamer elucidated KaiC intersubunit organization and how KaiC might function as a scaffold for the formation of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes (17). The KaiC structure also illuminated the mechanism of rhythmic phosphorylation of KaiC by identifying three essential phosphorylation sites at threonine and serine residues in KaiC at residues T426, S431, and T432 (14, 18). Moreover, phosphorylation of S431 and T432 occurs in an ordered sequence over the cycle of the in vitro KaiABC oscillator (19, 20). These phosphorylation events are likely to mediate conformational changes in KaiC that allow interaction with KaiB and subsequent steps in the molecular cycle (10).

Despite these insights, however, we do not know how the intermolecular interactions among KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC influence the dynamics of the cyanobacterial PTO. For example, given that KaiA stimulates KaiC autophosphorylation (10, 13, 14, 16) and that KaiA is associated with KaiC throughout the cycle (7), why then is KaiC not clamped in a constitutively hyperphosphorylated state over time? How might the interaction of KaiB with KaiA•KaiC influence KaiC phospho-state, and will this affect the dynamics of the system, including its emergent period? In this study, we found that there are two kinds of association of KaiA with KaiC; the first forms a labile phosphorylation-stimulating KaiA•KaiC complex that is present during the phosphorylation phase, and the second kind of association forms a very stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex during the dephosphorylation phase in which KaiA's stimulating ability is inactivated. In particular, we found that KaiB specifically forms stable complexes with hyperphosphorylated KaiC and then recruits and inactivates KaiA only after the KaiB•KaiC complex has formed. The labile KaiA•KaiC complex depends on the previously described interaction of KaiA with the C-terminal “tentacles” of KaiC, but the stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex can form in the complete absence of these C-terminal tentacles. Moreover, we found that mutant KaiB variants that exhibit altered rates of association with KaiC confer predictable changes in the period of the in vitro oscillator.

Results

Affinity of KaiA for KaiC Depends on KaiC Phosphorylation Status.

KaiA is known to bind to the C-terminal “tentacles” of KaiC (21, 22). Previous studies have suggested that a single KaiA dimer can promote the phosphorylation of a KaiC hexamer (23) and that the binding ratio between the KaiA dimer and the KaiC hexamer is 1:1 (22). On the other hand, measurements of the concentrations of KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC in vivo indicate that there are approximately five times as many KaiC hexamers as KaiA dimers (24), and the optimized conditions for in vitro cycling of the KaiABC oscillator use a ratio of one KaiA dimer to 1.3 KaiC hexamers (5). To estimate the dissociation constant between KaiA and KaiC, we used fluorescence anisotropy with labeled KaiA and increasing concentrations of unlabeled native KaiC (“KaiCWT”). On the basis of the anisotropy data (representative example shown in Fig. 1A) and the assumption of a 1:1 binding ratio, a Kd of ≈8 nM could be estimated for the KaiA–KaiCWT association. KaiCWT prepared under these conditions is predominantly phosphorylated. To assess whether the phosphorylation status of KaiC influences the Kd, we used mutant variants of KaiC that mimic its various phospho-states (SI Appendix, Table S1 summarizes the properties of the wild-type and mutant Kai proteins studied in this article). For example, KaiCEE is a mutant of KaiC with glutamate residues at positions 431 and 432 that mimics hyperphosphorylated KaiCWT (25), whereas KaiCAA is a mutant with alanine residues at positions 431 and 432 that mimics hypophosphorylated KaiCWT (26). These mutant KaiCs show significant differences in the Kd for interaction with KaiA. As depicted in Fig. 1B, the Kd for the “hyperphosphorylated” KaiCEE is much smaller (Kd ≈3 nM) than for the “hypophosphorylated” KaiCAA (Kd ≈32 nM). Therefore, the phosphorylation status of KaiC is likely to have a significant impact on binding of KaiA, such that KaiA has higher affinity for hyperphosphorylated KaiC than for hypophosphorylated KaiC.

Fig. 1.

Interactions among KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC. (A and B) Fluorescence anisotropy was used to calculate the binding affinity between KaiA and KaiC. (A) FA between KaiA and KaiCWT. F150-labeled KaiA (60 nM) was mixed with increasing concentrations of unlabeled KaiCWT proteins, and the anisotropy was measured. The dissociation constant (Kd) was calculated by assuming a 1:1 ratio binding stoichiometry between KaiA dimers and KaiC hexamers by the equation in ref. 29 and simulated by the curves shown on the panels. (B) FA between KaiA (60 nM) and KaiCAA or KaiCEE phosphomimics. (C–E) Formation of stable complexes among KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC was assayed by native PAGE. (C) Formation of stable complexes of KaiB with KaiCDT (Left) or KaiCEE (Right), as indicated by a reduction in the mobility of the KaiC band. (D) In the presence of KaiB, KaiA can be included in a stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex, as indicated by extra bands and the depletion of the free KaiA dimer band (KaiCDT, Left, and KaiCEE, Right). (E) In the case of a KaiC variant that cannot be phosphorylated on the S431 residue (KaiCAT), stable KaiB•KaiCAT (Left) or KaiA•KaiB•KaiCAT complexes do not form.

Formation of Stable Complexes of KaiC with KaiA and/or KaiB Depends on KaiC's Phosphorylation Status.

Although fluorescence anisotropy (as in Fig. 1 A and B) can be used to assess the Kd for both labile and stable associations, we found that some complexes of KaiC with KaiB ± KaiA were so stable that they could be measured by band shifts after electrophoresis of the proteins for 5 h in native polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 1 C–E). For these measurements, we used KaiCWT and KaiC variants that were mutated at the 431 and 432 residues to mimic the various phosphorylation states that are sequentially present over the in vitro oscillation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (19, 20). SI Appendix, Fig. S2A shows the electrophoretic patterns for the different KaiC variants by SDS/PAGE or native-PAGE. KaiCWT, KaiCAT, and KaiCDT exhibit a temperature-dependent change in the phosphorylation status as assessed by mobility shifts after SDS/PAGE. In particular, each of these variants is predominantly in a hyperphosphorylated state after incubation at 4 °C for 24 h, whereas they are predominantly hypophosphorylated after incubation at 30 °C for 24 h. On the other hand, KaiCAA and KaiCDA are in a hypophosphorylated state independent of incubation temperature; conversely, KaiCEE is always in a hyperphosphorylated state, and KaiCAE is “halfway” phosphorylated by virtue of a glutamate at position 432 and a nonphosphorylatible alanine at position 431 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). By native PAGE, all versions of KaiC are predominantly in the hexameric configuration, but there is a significant monomer pool for both KaiCEE and KaiCDT (as indicated by the presence of lower MW bands in SI Appendix, Fig. S2A).

The data of Fig. 1B suggest that KaiA interacts more strongly with hyperphosphorylated KaiC, and the same is true for interactions between KaiB and KaiC. In fact, KaiB will form a stable interaction with hyperphosphorylated KaiC that will persist through native PAGE electrophoresis for 5 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C) and can be visualized by a mobility shift in the native PAGE (at 30 °C, these KaiB•KaiC complexes are maintained for at least several days). Fig. 1C shows that KaiB forms stable complexes over 1–4 h incubation with KaiCDT and KaiCEE, which are both mimics of hyperphosphorylated KaiC. KaiB does not form these stable complexes with mimics of different forms of hypophosphorylated KaiC, KaiCAA, KaiCAE, KaiCDA, or KaiCAT (Fig. 1E, Left, and SI Appendix, Fig. S2D, Left). Interestingly, although KaiA alone can form labile associations with KaiC (Fig. 1 A and B), it does not form the stable complexes as assayed by native PAGE in the absence of KaiB (SI Appendix, Fig. S2E). On the other hand, when KaiB is present, stable complexes of KaiA and KaiB with hyperphosphorylated KaiC mimics can be found by native PAGE, as seen by mobility shifts and depletion of the KaiA dimer band (Fig. 1D). These associations are dependent upon KaiC, because KaiA and KaiB do not form complexes by themselves that are stable enough to be measured by this native PAGE method (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). Finally, the formation of these stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes is dependent upon the phosphorylation status of KaiC; hyperphosphorylated KaiC (KaiCDT and KaiCEE) will allow the formation of a stable complex of all three proteins (Fig. 1D), but hypophosphorylated KaiCAT will not (Fig. 1E, Right). Therefore, hyperphosphorylated KaiC will form stable complexes with KaiB into which KaiA can be incorporated to form stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes, but in the absence of KaiB the associations of KaiA with hyperphosphorylated KaiC are not stable (Figs. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2E). Moreover, the time course data of the formation of these stable complexes can be used to model the dynamics of the KaiABC oscillator (see below).

Rhythmic Assembly/Disassembly of Stable KaiABC Complexes During the in Vitro Oscillation.

The data of Fig. 1B used phosphomimetic mutants of KaiC to provide snapshots of the association dynamics that oscillate over the KaiC phosphorylation cycle. The rhythmic changes can also be measured directly with KaiCWT to confirm that the phosphomimics accurately reflect the characteristics of KaiCWT. In this analysis, we took advantage of two mutants of KaiB that show different circadian periods in vivo and in vitro: one mutant replaces the arginine at site 22 with cysteine (KaiBR22C) and the other replaces arginine at site 74 with cysteine (KaiBR74C). In vivo, KaiBWT exhibits a period of 24.9 ± 0.1 h, KaiBR74C has a period of 21.7 ± 0.1 h, and KaiBR22C has a period of 26.2 ± 0.1 h (Figs. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Table S1). In vitro, the same trends in period are obvious (Fig. 2C). These KaiB variants have different kinetics of formation of KaiB•KaiC complexes (as assayed with the KaiC489 mimic of hyperphosphorylated KaiC for technical reasons explained in SI Appendix, SI Methods). KaiB interacts with hyperphosphorylated KaiC (± KaiA) to form stable KaiB•KaiC or KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes (Fig. 1 C and D). At the beginning of the phosphorylation phase in the in vitro oscillation, the ratio of KaiB to hyperphophorylated KaiC (KaiB/KaiC-P) is high (19, 20). As illustrated in Fig. 2D, formation of stable KaiB•KaiC489 complexes occurs most rapidly with the short period KaiBR74C mutant and most slowly with the long period KaiBR22C mutant (for raw data, see SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Although these KaiB mutants affected the kinetics of KaiB•KaiC complex formation, Fig. 2E shows that the appearance of the KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes with the KaiB mutants was indistinguishable from that of KaiA•KaiB•KaiCWT complexes visualized with electron microscopy by methods described previously (7).

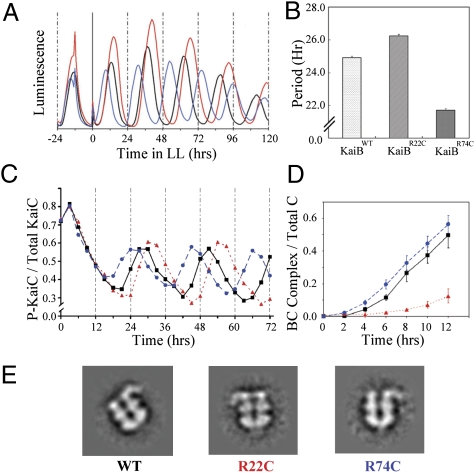

Fig. 2.

KaiB mutant variants that affect association kinetics also affect circadian period in vivo and in vitro. In this figure, black traces are KaiBWT, red traces are KaiBR22C (long period), and blue traces are KaiBR74C (short period). (A) Luminescence traces of cyanobacterial strains expressing different KaiB variant proteins in vivo. (B) Quantitative analysis of the periods in A: KaiBWT = 24.9 ± 0.10 h; KaiBR22C = 26.2 ± 0.12 h; KaiBR74C = 21.7 ± 0.10 h (mean ± SD, n = 3 for each variant). (C) In vitro rhythms with KaiAWT + KaiCWT and each of the three KaiB mutant variants. The mutations of KaiB show similar effects on the in vitro rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation as on the in vivo rhythm of gene expression as reported by luminescence in A. (D) Formation of complexes between KaiC489 and the three KaiB mutant variants (±SD, n = 3; for raw data, see SI Appendix, Fig. S3). (E) Electron microscopy analyses of the stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes show similar configurations among the different KaiB variants.

KaiA and KaiB rhythmically interact with KaiCWT to assemble/disassemble stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes during the in vitro oscillation. As shown in Fig. 3A, in vitro oscillations of KaiC phosphorylation status visualized by SDS/PAGE (Fig. 3A, Upper) are paralleled by oscillations in stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes indicated by native PAGE (Fig. 3A, Lower), such that the peak in the abundance of complexes occurs 6–8 h after the peak in KaiC phosphorylation (Fig. 3E). The amount of stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes can be quantified as a “complexes index” (CI) that is plotted for in vitro oscillations of KaiCWT and KaiA with KaiBWT (Fig. 3C), KaiBR74C (Fig. 3B and raw data in SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), and KaiBR22C (Fig. 3D and raw data in SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). The modeling study of van Zon et al. (27) predicted that KaiB•KaiC complexes would sequester KaiA rhythmically during the in vitro oscillation (also see ref. 20). This prediction is upheld by our data. As KaiA is incorporated into the KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes, it is sequestered so that free KaiA levels decrease, which leads to a depletion of the free KaiA dimer band on native PAGE (Fig. 1D). Thus, if the prediction of van Zon et al. (27) were correct, then the CI should oscillate in antiphase to the level of free KaiA dimers. This antiphase oscillation is obvious for the KaiBR22C data (Fig. 3D and raw data in SI Appendix, Fig. S4B) and although less conspicuous for KaiBWT or KaiBR74C, there is nevertheless a significant antiphase relationship between the oscillations of free KaiA dimers and KaiA• KaiBWT•KaiC or KaiA• KaiBR74C•KaiC complexes (Fig. 3 A–C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A).

Fig. 3.

Rhythmic assembly of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes quantitatively correlate with KaiC phosphostatus. (A, Upper) Using KaiAWT, KaiBWT, and KaiCWT, samples were collected every 4 h during the in vitro oscillation and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and native PAGE. Each lane of the SDS/PAGE gel clearly shows four bands representing the four phosphoforms of KaiCWT (19, 20). These data are quantified in E (Lower). (A, Lower) The same samples were run on native PAGE, and low-mobility KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes appear and disappear rhythmically in antiphase to the density of the KaiC hexamer and KaiA dimer bands (the image comes from two separate gels, hence the discontinuity of the last three lanes). (B) Quantification of the formation of complexes (solid line) and free KaiA (dashed line) in the native PAGE for KaiBR74C (raw data appears in SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). (C) Same as for B except using KaiBWT (raw data appears in A). (D) Same as for B except using KaiBR22C (raw data appears in SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). The period of the rhythm of Kai protein complex formation is comparable to the in vivo luminescence rhythm and the in vitro KaiC phosphorylation rhythms. (E) The formation of complexes (Upper) is compared with the KaiC phosphorylation rhythm (Lower) (raw data in A). Formation of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes peaks in the phase of KaiC dephosphorylation. (F) Relationship between formation of complexes and different KaiC phosphoforms. The analysis of KaiC phosphorylation status and phosphoforms was derived from SDS/PAGE gels as shown in SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S5). The short period mutant KaiBR74C is plotted with the long period mutant KaiBR22C to show the maximum contrast (the peaks for KaiBWT were intermediate between those for KaiBR74C and KaiBR22C, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The formation of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes (Top), doubly phosphorylated KaiC (S431-P and T432-P; Middle), and singly phosphorylated KaiC (S431-P; Bottom) were plotted as a function of incubation time. The blue bar is a reference for the peak of KaiA•KaiBR74C•KaiC complex formation, whereas the red bar is a reference for the peak of KaiA•KaiBR22C•KaiC complex formation.

The oscillation in stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes occurs in a strict phase relationship to the KaiC phosphorylation status. As mentioned above for the data of Fig. 3A, the oscillation of CI phase lags the oscillation of KaiC's overall level of phosphorylation by 6–8 h (Fig. 3E). Fig. 3F depicts the relationships between CI and specific KaiC phosphoforms; the peak of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC formation occurs just after the peak of KaiC that is doubly phosphorylated (on both S431 and T432, i.e., “ST-KaiC”) and just before the peak of singly phosphorylated KaiC (on S431, i.e., “S-KaiC”). The temporal relationships between these rhythms are consistent with the interpretation that doubly phosphorylated KaiC (ST-KaiC) regulates the formation of the KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes, and these complexes then mediate the dephosphorylation of the T432 residue to form singly phosphorylated KaiC (S-KaiC) in the sequential reaction (19, 20) (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S5).

Modeling of PTO Dynamics as a Function of KaiA and KaiB Associations with KaiC.

In this section we briefly describe a mathematical model for the KaiABC in vitro oscillator based on mass action that includes monomer exchange as a mechanism of synchrony and KaiA sequestration in complexes with KaiB•KaiC during the dephosphorylation stage (see SI Appendix, SI Methods for a complete list of equations and parameters used). We have previously shown in an explicit stochastic matrix model for hexamers that phase-dependent monomer exchange is sufficient to produce sustained oscillations in the KaiABC system (7). Here we construct and use a simplified ordinary differential equation (ODE) model to investigate the dynamics of KaiA sequestration and the effects of KaiB association/dissociation rates on the oscillator.

In a simplified ODE version of the more complete model, the series of molecular reactions in the KaiABC system are organized into the cyclic reaction sequence: C0 → AC0 → AC1 … → ACN → ABCN → ABCN -1 → … → ABC0 → A+B+C0. We label the concentration of effective hexamer phosphorylation states by Ci (1 < i < N). Complexes of KaiA•KaiC with various phosphorylation levels are indicated by ACi; similarly, various phosphorylation levels of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes are labeled by ABCi. The concentration of maximally hyperphosphorylated KaiC states is indicated by N [N is 12 to account for the two phosphorylation sites (S431 and T432) in each monomer of the hexamer]. In the full model (SI Appendix, SI Methods), we (i) remove the assumption of the explicit reaction sequence accounting for autophosphorylation/dephosphorylation reactions, (ii) include all uncomplexed (Ci) states, (iii) include both association and dissociation reactions for all complexes, and (iv) explicitly model the sequestration process of KaiA by KaiB•KaiCN using the reaction: A + BCN ↔ ABCN. Because KaiA rapidly binds KaiC and KaiC readily phosphorylates in these KaiA•KaiC complexes, the phosphorylation phase is well approximated by the simple sequence C0 → AC0 → AC1 …→ ACN without considering each reaction separately (i.e., Ci ↔ Ci+1, ACi ↔ A+ Ci, ACi ↔ ACi+1) that is contained in the full model. Therefore, in our simplified ODE model, KaiB only binds to the hyperphosphorylated form of KaiC (B + ACN → ABCN), which subsequently dephosphorylates through each intermediate state that characterizes the dephosphorylation phase, ABCN → ABCN -1 → …→ ABC0. Experimentally, KaiC that is associated with KaiB seems to dephosphorylate at the same rate as free KaiC (15, 28). Finally the hypophosphorylated complexes dissociate, releasing KaiA, KaiB, and unphosphorylated KaiC: ABC0 → A+B+C0.

By itself this cyclic reaction sequence will not produce sustained oscillations, owing to desynchronization of the hexamers in the population (leading to damped oscillations). On the basis of the experimental data (7, 26), we use the exchange of monomers among hexamers as a mechanism for sustained oscillations (7). We implement exchange using the reactions ACi +ACj → ACi+1 + ACj-1 (j > i) and ABCi +ABCj → ABCi+1 + ABCj-1 (j > i), indicating transfer of a phosphate from a higher phosphorylated state (j) to a lower phosphorylated state. The simplified ODE model has the advantage that it is more easily interpreted and contains only six rates: one effective phosphorylation rate, one effective dephosphorylation rate, a KaiA binding rate, a KaiB binding rate, a complex dissociation rate, and an exchange rate. A typical simulation of the net population phosphorylation with standard initial conditions of [KaiA dimer]:[KaiB tetramer]:[KaiC hexamer] = 1:1.5:1 (setting C0 = 1 μM) is shown in Fig. 4A, which shows the sustained circadian nature of the oscillation. The kinetics of sequestration of KaiA in high-molecular-weight complexes (with KaiB and KaiC) is indicated in Fig. 4B,which shows the rapid formation of labile KaiA•KaiC complexes followed by sequestration into stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes. There is a ≈6-h delay between the peak of the phosphorylation rhythm and the peak of KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex formation, which is similar to the experimental data depicted in Fig. 3E. To examine the effect of KaiB binding on the dynamics, we varied the rate of KaiB binding to hyperphosphorylated KaiC. As shown in Fig. 4C, a faster binding rate decreases the period, whereas a slower binding rate increases the period and decreases the amplitude of the KaiC phosphorylation rhythm. These results are qualitatively and quantitatively similar to the trends in the experimental data of Fig. 2 A–C. The complete model also displays similar circadian dynamics of complexes as the simple model. Therefore, a relatively simple model based on the empirical data of KaiA and KaiB interactions with KaiC indicates that the mechanisms of monomer exchange and sequestration of KaiA are sufficient to reproduce various circadian dynamics we have observed in the oscillator.

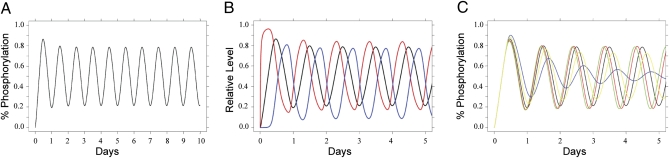

Fig. 4.

Computational model of the dynamics of KaiABC complexes. (A) Typical simulation from the simplified mathematical model of the net KaiC population phosphorylation with standard initial conditions of [KaiA dimer]:[KaiB tetramer]:[KaiC hexamer] = 1:1.5:1 and setting C0 = 1 μM. (B) Kinetics of sequestration of KaiA in high-molecular-weight complexes (with KaiB and KaiC) shows the rapid formation of labile KaiA•KaiC complexes (red trace) followed by sequestration into stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes (blue trace). The black trace is net KaiC phosphorylation. (C) The simulated effect of varying the association kinetics of KaiB to hyperphosphorylated KaiC on net KaiC phosphorylation shows a correlation between an increased rate of association (5.0 = green, 2.5 = red, 1.0 = black, 0.5 = yellow, 0.25 = blue) and a shorter circadian period.

Recruitment of KaiA to the Stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC Complex Occurs at a Unique Site on KaiC.

KaiA is thought to enhance the autokinase activity of KaiC by interacting with the C-terminal tentacles of KaiC (10, 16, 21). However, removing the 30-aa tentacles from the C terminus of KaiC (to create KaiC489) does not prevent the formation of stable complexes with either KaiB or KaiA/KaiB. As shown by the native PAGE analyses in Fig. 5, KaiC489 forms stable complexes with KaiB (Middle). KaiC489 does not form stable KaiA•KaiC489 complexes, but when KaiB is present KaiC489 will sequester KaiA into a stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC489 complex (Fig. 5). KaiC489 forms hexamers but has a slightly higher mobility than KaiCWT in native PAGE due to its loss of 30 residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A); λ-PPase treatment confirmed that the multiple bands of KaiC489 observed by SDS/PAGE are a result of phosphorylation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). As reported by Kim et al. (16), KaiC489 maintains its autokinase activity but has a reduced autophosphatase activity, so it hyperphosphorylates over time to reach a steady state of doubly phosphorylated S431 and T432 residues (ST-KaiC489) independently of KaiA (Fig. 5, Lower, and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Therefore, the native PAGE data strongly support the interpretation that KaiA is sequestered into complexes with KaiB and KaiC by an interaction that is independent of KaiC's C-terminal tentacles. Possibly this unique site on KaiC is created by the binding of KaiB to KaiC (possibly KaiB itself provides a part of the KaiA binding site), which could explain the KaiB-dependency of the formation of stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes.

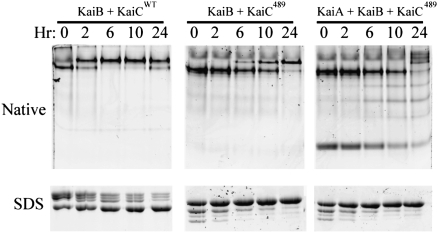

Fig. 5.

KaiC489 forms stable complexes with KaiB and KaiA. KaiC489 (from which the 30 amino acids that form “tentacles” at the C terminus of KaiC were deleted) forms a hexamer that can assemble into a stable KaiB•KaiC complex (Center) as well as a stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex (Right). KaiCWT also forms stable KaiB•KaiC complexes (Left). These data indicate that the formation of the stable complex of KaiA with KaiC in the presence of KaiB is independent of KaiC's C-terminal tentacles. Note from the SDS/PAGE analyses at the bottom of the figure that KaiCWT dephosphorylates over time at 30 °C (Left), but KaiC489 hyperphosphorylates over time at 30 °C (Center) independently of the presence of KaiA.

Discussion

Terauchi et al. (8) have proposed that the rhythm of KaiC ATPase activity constitutes the most fundamental reaction underlying circadian periodicity in cyanobacteria. Another possibility, however, is that the ATP hydrolysis observed by Terauchi et al. is a consequence of the energy released by the conformational changes of KaiC that are regulated by the associations with KaiA and KaiB. Our results support the latter interpretation. We find that the intermolecular dynamics of interaction among KaiA and KaiB with KaiC determine the period and amplitude of this in vitro oscillator. It is possible that the ATPase activity is a reflection of an underlying biochemical activity of KaiC that has not yet been identified. Consequently, our hypothesis is that (i) the basic timing loop of the KaiABC oscillator and (ii) its outputs are mediated by conformational changes of KaiC in association with KaiA and KaiB.

For example, mutations within KaiB that alter affinity to KaiC predictably alter the period of this clock in vivo and in vitro, as confirmed by our mathematical modeling. Therefore, with native versions of KaiC and KaiA, mutations within KaiB that change affinity to KaiC will modulate key circadian properties, which is consistent with the hypothesis that intermolecular associations determine KaiABC oscillator dynamics. At the very least, if the ATPase activity is the basic timing loop as suggested by Terauchi et al. (8), then the intermolecular associations with KaiB must regulate the ATPase activity in a deterministic way. Our interpretation is that the formation of Kai protein complexes is coupled with KaiC phosphorylation status; because different KaiB variants modulate the rate of KaiB•KaiC formation, they affect the period of the KaiC phosphorylation. Our modeling analysis confirms that this interpretation is consistent with the empirical data.

Another important conclusion from our study is that we found that the characteristics of KaiA's association with KaiC go through two phases—during the phosphorylation phase in which KaiA is stimulating KaiC's autophosphorylation, the association of KaiA with KaiC is labile. However, in the later dephosphorylation phase, a stable KaiB•KaiC complex recruits KaiA into a stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex that facilitates KaiC's dephosphorylation because it sequesters KaiA into an inactive configuration (20, 27). The stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiCWT complex can be mimicked by associations of KaiA and KaiB with the hyperphosphorylated KaiC489 mutant. Even though KaiC489 is devoid of the C-terminal tentacles (and cannot therefore associate with KaiA by itself), it forms stable complexes with KaiB, and this KaiB•KaiC489 complex can recruit KaiA into a complex that is so stable it resists dissociation during electrophoresis through a native gel (Figs. 5 and 6A). In the case of the cyclic reaction with KaiCWT, KaiA first repetitively interacts with the tentacles of hypophosphorylated KaiC to enhance KaiC's autokinase activity until KaiC is hyperphosphorylated, at which time the KaiC hexamer undergoes a conformational change that allows it to form a stable complex with KaiB (Fig. 6B) (6, 7, 10, 13, 16, 21). This stable KaiB•KaiC complex exposes a unique binding site for KaiA, which sequesters KaiA into the stable KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complex that is visualized in Fig. 2E. The sequestered KaiA is unable to further stimulate KaiC's autokinase activity, and therefore the autophosphatase activity dominates, such that KaiC dephosphorylates to its hypophosphorylated conformation, from which KaiB and KaiA dissociate and the cycle begins anew (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

KaiB•KaiC sequesters KaiA. (A) KaiC489 (“double-donut” hexamer) cannot associate with KaiA (red dimers) by itself, but once it has become hyperphosphorylated (phosphorylated residues indicated by red dots within the KaiC hexamer), it can form stable complexes with KaiB (tetramer of green diamonds) that are then able to recruit KaiA into KaiA•KaiB•KaiC complexes. (B) With KaiCWT (“double-donut” hexamer with C-terminal “tentacles”) in the cycling reaction, KaiA repeatedly and rapidly interacts with KaiC's C-terminal tentacles during the phosphorylation phase. When KaiCWT becomes hyperphosphorylated, it first binds KaiB stably. Then the KaiB•KaiC complex binds KaiA, sequestering it from further interaction with KaiC's tentacles. At that point, KaiC initiates dephosphorylation. When KaiC is hypophosphorylated, it releases KaiB and KaiA, thereby launching a new cycle.

Our conclusion of a labile interaction between KaiA and KaiC during the phosphorylation phase is consistent with previous experimental studies (6, 16, 21). On the other hand, there are no previous empirical data supporting a stably sequestered KaiA complex. The hypothetical existence of a sequestered KaiA complex had been suggested previously in a modeling paper as a potential mechanism for maintaining synchrony within a population of KaiC hexamers (27). However, in our model the sequestration of KaiA is used as a means by which KaiCWT shifts between a predominantly autokinase mode and a predominantly autophosphatase mode. Moreover, we model the primary mechanism for maintaining synchrony among KaiC hexamers as residing in the phenomenon of KaiC monomer exchange among the hexamers in the population of complexes, which is an interpretation that is strongly supported by experimental data (7, 26). Therefore, our data provide concrete experimental support for the existence of a KaiB•KaiC complex that sequesters KaiA into a stable three-protein complex whose function is to inactivate the phosphorylation-stimulating properties of KaiA and thus initiate the dephosphorylation phase. Our empirical data are integrated with a mathematical model that demonstrates the hierarchy of these relationships.

Methods

Complete methods, including description of the mathematical modeling and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S6, are described in SI Appendix, SI Methods. Cyanobacterial strains were Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 wild type and mutants grown in BG-11 medium (15). Luminescence rhythm measurements as a reporter of circadian gene expression in vivo were as described previously (15). KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC proteins from S. elongatus were purified and the in vitro oscillation was performed as described previously (7). The native forms of the Kai proteins are indicated herein as KaiAWT, KaiBWT, and KaiCWT; nomenclature for naming KaiB and KaiC mutant variants is described in SI Appendix, SI Methods. Analyses of Kai protein interactions by native PAGE, electron microscopy, and fluorescence anisotropy methods are described in SI Appendix, SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues for helpful discussions, in particular Drs. Martin Egli, Phoebe Stewart, Yao Xu, Rekha Pattanayek, and Mark Woelfle. This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grants GM067152 (to C.H.J.) and GM081646 (to Dr. Phoebe Stewart).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1002119107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ditty JL, Mackey SR, Johnson CH, editors. Bacterial Circadian Programs. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, et al. Circadian orchestration of gene expression in cyanobacteria. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1469–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RM, Williams SB. Circadian rhythms in gene transcription imparted by chromosome compaction in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8564–8569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508696103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woelfle MA, Xu Y, Qin X, Johnson CH. Circadian rhythms of superhelical status of DNA in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18819–18824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706069104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakajima M, et al. Reconstitution of circadian oscillation of cyanobacterial KaiC phosphorylation in vitro. Science. 2005;308:414–415. doi: 10.1126/science.1108451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kageyama H, et al. Cyanobacterial circadian pacemaker: Kai protein complex dynamics in the KaiC phosphorylation cycle in vitro. Mol Cell. 2006;23:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori T, et al. Elucidating the ticking of an in vitro circadian clockwork. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e93. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terauchi K, et al. ATPase activity of KaiC determines the basic timing for circadian clock of cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16377–16381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomita J, Nakajima M, Kondo T, Iwasaki H. No transcription-translation feedback in circadian rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation. Science. 2005;307:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1102540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson CH, Egli M, Stewart PL. Structural insights into a circadian oscillator. Science. 2008;322:697–701. doi: 10.1126/science.1150451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki H, Taniguchi Y, Ishiura M, Kondo T. Physical interactions among circadian clock proteins KaiA, KaiB and KaiC in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 1999;18:1137–1145. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taniguchi Y, et al. Two KaiA-binding domains of cyanobacterial circadian clock protein KaiC. FEBS Lett. 2001;496:86–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasaki H, Nishiwaki T, Kitayama Y, Nakajima M, Kondo T. KaiA-stimulated KaiC phosphorylation in circadian timing loops in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15788–15793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222467299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiwaki T, et al. Role of KaiC phosphorylation in the circadian clock system of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13927–13932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403906101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Mori T, Johnson CH. Cyanobacterial circadian clockwork: Roles of KaiA, KaiB and the kaiBC promoter in regulating KaiC. EMBO J. 2003;22:2117–2126. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YI, Dong G, Carruthers CW, Jr, Golden SS, LiWang A. The day/night switch in KaiC, a central oscillator component of the circadian clock of cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12825–12830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800526105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattanayek R, et al. Visualizing a circadian clock protein: Crystal structure of KaiC and functional insights. Mol Cell. 2004;15:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, et al. Identification of key phosphorylation sites in the circadian clock protein KaiC by crystallographic and mutagenetic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13933–13938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404768101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishiwaki T, et al. A sequential program of dual phosphorylation of KaiC as a basis for circadian rhythm in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 2007;26:4029–4037. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rust MJ, Markson JS, Lane WS, Fisher DS, O'Shea EK. Ordered phosphorylation governs oscillation of a three-protein circadian clock. Science. 2007;318:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.1148596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vakonakis I, LiWang AC. Structure of the C-terminal domain of the clock protein KaiA in complex with a KaiC-derived peptide: Implications for KaiC regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10925–10930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403037101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pattanayek R, et al. Analysis of KaiA-KaiC protein interactions in the cyano-bacterial circadian clock using hybrid structural methods. EMBO J. 2006;25:2017–2028. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi F, et al. Stoichiometric interactions between cyanobacterial clock proteins KaiA and KaiC. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitayama Y, Iwasaki H, Nishiwaki T, Kondo T. KaiB functions as an attenuator of KaiC phosphorylation in the cyanobacterial circadian clock system. EMBO J. 2003;22:2127–2134. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitayama Y, Nishiwaki T, Terauchi K, Kondo T. Dual KaiC-based oscillations constitute the circadian system of cyanobacteria. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1513–1521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1661808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito H, et al. Autonomous synchronization of the circadian KaiC phosphorylation rhythm. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Zon JS, Lubensky DK, Altena PR, ten Wolde PR. An allosteric model of circadian KaiC phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7420–7425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608665104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y, et al. Intramolecular regulation of phosphorylation status of the circadian clock protein KaiC. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovaleski BJ, et al. In vitro characterization of the interaction between HIV-1 Gag and human lysyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19449–19456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.