Abstract

Among eukaryotes, four major phytoplankton lineages are responsible for marine photosynthesis; prymnesiophytes, alveolates, stramenopiles, and prasinophytes. Contributions by individual taxa, however, are not well known, and genomes have been analyzed from only the latter two lineages. Tiny “picoplanktonic” members of the prymnesiophyte lineage have long been inferred to be ecologically important but remain poorly characterized. Here, we examine pico-prymnesiophyte evolutionary history and ecology using cultivation-independent methods. 18S rRNA gene analysis showed pico-prymnesiophytes belonged to broadly distributed uncultivated taxa. Therefore, we used targeted metagenomics to analyze uncultured pico-prymnesiophytes sorted by flow cytometry from subtropical North Atlantic waters. The data reveal a composite nuclear-encoded gene repertoire with strong green-lineage affiliations, which contrasts with the evolutionary history indicated by the plastid genome. Measured pico-prymnesiophyte growth rates were rapid in this region, resulting in primary production contributions similar to the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus. On average, pico-prymnesiophytes formed 25% of global picophytoplankton biomass, with differing contributions in five biogeographical provinces spanning tropical to subpolar systems. Elements likely contributing to success include high gene density and genes potentially involved in defense and nutrient uptake. Our findings have implications reaching beyond pico-prymnesiophytes, to the prasinophytes and stramenopiles. For example, prevalence of putative Ni-containing superoxide dismutases (SODs), instead of Fe-containing SODs, seems to be a common adaptation among eukaryotic phytoplankton for reducing Fe quotas in low-Fe modern oceans. Moreover, highly mosaic gene repertoires, although compositionally distinct for each major eukaryotic lineage, now seem to be an underlying facet of successful marine phytoplankton.

Keywords: comparative genomics, primary production, prymnesiophytes, marine photosynthesis, haptophytes

Global primary production is partitioned equally among terrestrial and marine ecosystems, each accounting for ≈50 gigatons of carbon per year (1). The phytoplankton responsible for marine primary production include the cyanobacteria, Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, and a multitude of eukaryotic phytoplankton, such as diatoms, dinoflagellates, prasinophytes, and prymnesiophytes (2–4). Most oceanic phytoplankton are “picoplanktonic” (<2–3 μm diameter) and have high surface area to volume ratios, an advantage in open-ocean low-nutrient conditions (5–8). Despite the importance of eukaryotic phytoplankton to carbon cycling only six genomes have been sequenced and analyzed comparatively, all being from diatoms and prasinophytes. These revealed greater differentiation than anticipated on the basis of 18S rRNA gene analyses (9–11). The observed genomic divergence is associated with major differences in physiology and niche adaptation (10).

Pigment-based estimates indicate that prymnesiophytes, also known as haptophytes, are broadly distributed and abundant. Oceanic prymnesiophytes are thought to be small owing to high levels of prymnesiophyte-indicative pigments in regions where most Chl a (representing all phytoplankton combined) is in the <2-μm size fraction (6, 12). Six picoplanktonic prymnesiophytes exist in culture (6, 7) but prymnesiophyte 18S rDNA sequences from <2–3-μm size-fractioned environmental samples typically belong to uncultured taxa (6, 13–15). As a whole, this lineage reportedly diverged from other major eukaryotic lineages early on, 1.2 billion years ago (16), and their overall placement among eukaryotes is uncertain (4, 16). They are extremely distant from phytoplankton with published genomes. Thus, although inferences exist regarding their importance and evolutionary history, uncertainties surround even the most basic features of oceanic pico-prymnesiophytes, such as cell size, biomass, growth rates, and genomic composition.

One approach for gaining insights to uncultivated taxa is metagenomics. However, unicellular eukaryotes have larger genomes and lower gene density than marine bacteria and archaea and are less abundant, making efficient sequence recovery difficult by seawater filtration. Parsing of eukaryotic data from diverse communities is particularly problematic owing to the paucity of relevant reference genomes. Selection of DNA from an uncultivated target microbe(s) (e.g., by fosmid sequencing or using cells sorted by flow cytometry) obviates bioinformatic parsing issues and has revealed unique gene complements in uncultured prokaryotes (17, 18).

To address uncertainties regarding pico-prymnesiophyte ecology, we integrated a suite of cultivation-independent methods. Targeted metagenomics was developed to investigate diversity and genomic features of uncultivated pico-prymnesiophytes. Growth rates were measured and used to assess primary production in the same region. Building on this contextual dataset, biomass contributions were evaluated across provinces spanning tropical to subpolar systems, providing a comprehensive view of global importance and latitudinal variations.

Results and Discussion

Eukaryote-Targeted Metagenomics Approach and Diversity Context.

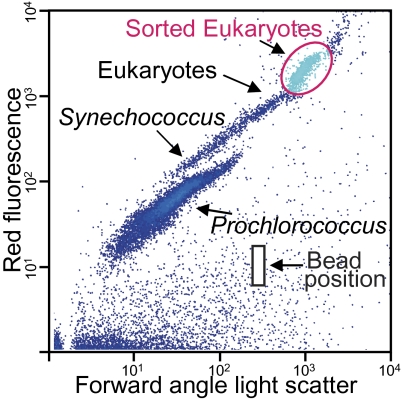

Photosynthetic picoeukaryote populations were sorted by flow cytometry (hereafter “sorted” or “the sort”) based on scatter and autofluorescence characteristics from two subtropical North Atlantic samples collected in the Florida Straits (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 Inset, and SI Materials and Methods, Sections 1 and 2). Whole-genome amplification (19) was performed on sorted target populations (SI Materials and Methods, Section 3), providing unprecedented access to pico-prymnesiophyte DNA.

Fig. 1.

Forward angle light scatter and chlorophyll-derived red fluorescence characteristics of picophytoplankton groups (at Florida Straits Station 04; Fig. 2 Inset, blue arrow), including the metagenome population (magenta circle) and showing the position of 0.75-μm bead standards (black box, not added to actual sort to avoid contamination).

Fig. 2.

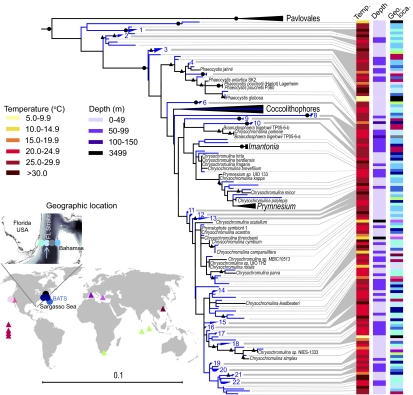

Maximum-likelihood reconstruction of (blue lines) environmental and (black) cultured prymnesiophyte 18S rDNA sequences from two sorts and 25 size-fractionated samples from discrete depths, dates, and locations (circles; Table S1) and previous publications (triangles) (SI Materials and Methods, Section 4). The Station 04 sort (blue arrow) was in the Gulf Stream core. A single representative was used for redundant sequences within each library. Supported clades composed of only environmental sequences were collapsed after tree building when of ≥99% identity (blue groups 1–22; Table S2). Node support is shown for (black circles) 100% and (black triangles) ≥75% support. Uncultured prymnesiophytes have also been seen recently in the South Pacific (40).

The sorted pico-prymnesiophytes were distinct from cultured taxa but closely related to environmental sequences from native populations. 18S rDNA clone libraries built from the sort DNA were analyzed within the context of <2–3 μm size-fractionated clone libraries from the Florida Straits, the Sargasso Sea, the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 2, SI Materials and Methods, Section 4, Fig. S1A, and Table S1), and published data. Similar to other studies (6, 13, 15), the vast majority of sequences were from uncultured prymnesiophytes. The majority of prymnesiophyte sequences from the Florida Straits Station 04 sort belonged to environmental group 8 (111 clones, 99–100% identity; Fig. S1B), also present in the easterly Station 08 sort. Lower levels of group 3 were detected in the Station 04 sort (7 clones, 99–100% identity), along with sequences at the tip of the tree (e.g., group 15; SI Materials and Methods, Section 5). Group 8 was also seen in the Sargasso Sea (14) and on multiple dates in the Florida Straits (Table S2). Group 8 had only 93% 18S rDNA identity to any cultured organism (to Chrysochromulina), and phylogenetic placement was unresolved (no bootstrap support).

The observed level of group 8 18S rDNA divergence has important implications for gene content. The diatoms Thalassiosira pseudonana and Phaeodactylum tricornutum, with 90% 18S rDNA identity, share only 30–40% of their genes and occupy fundamentally different niches (10). Of the four picoeukaryote genomes (all prasinophytes), two Micromonas isolates, with 97% 18S rDNA identity, have 69.5% DNA identity over aligned genome regions, sharing at most 90% of their protein-encoding genes (11). Although an unpublished genome of the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi is available, this prymnesiophyte is larger than the pico-prymnesiophytes and expected to occupy a distinct niche (8, 16). Furthermore, the soft-bodied prymnesiophytes in the sort were distant from coccolithophores (Fig. 2), a group known for their calcium carbonate plates (16).

Given the differences between the group 8–enriched sort population and cultured taxa, we used targeted metagenomics to discover genomic features of environmentally relevant pico-prymnesiophytes. Station 04 sort DNA was sequenced by 454-FLX and Sanger technologies (SI Materials and Methods, Section 5). Genes were modeled on assembled scaffolds and then screened phylogenetically using the E. huxleyi nuclear genome. For selection, half the identifiable genes on a scaffold had to clade directly with E. huxleyi, to the exclusion of gene sequences from all other taxa (SI Materials and Methods, Section 6). This ensured that only prymnesiophyte-derived scaffolds were further analyzed, because the stramenopile Pelagomonas fell partially in the same flow-cytometric population (SI Materials and Methods, Section 5). Seventy-one percent of genes on selected scaffolds were sistered by E. huxleyi genes, demonstrating screening rigor; only this scaffold subset (2 MB of assembly) was considered unambiguously pico-prymnesiophyte derived and used for comparative analyses. Twenty-nine percent of genes on pico-prymnesiophyte scaffolds seemed to be missing from E. huxleyi, supporting their distance from coccolithophores.

Gene Density and Genome Size Predictions.

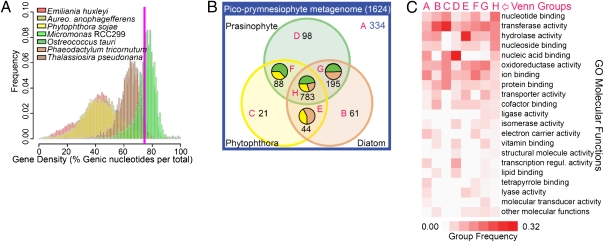

Prymnesiophytes are currently placed in the controversial eukaryotic Supergroup Chromalveolata along with stramenopiles (e.g., diatoms) and alveolates (e.g., dinoflagellates) but separate from the Supergroup Archaeplastida, which includes prasinophytes and all green-lineage organisms (e.g., land plants). However, their genome characteristics are unknown and phylogenetic placement uncertain. We found high gene density in the pico-prymnesiophyte metagenome (Fig. 3A and SI Materials and Methods, Section 7), akin to pico-prasinophytes, which purportedly underwent genome streamlining to optimize life in oligotrophic niches (9, 11). GC content was 60%.

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of the pico-prymnesiophyte metagenome. (A) Gene density histograms as the proportion of nucleotides in genes over all chromosomes within an incrementally sampled sliding window in prasinophytes and photosynthetic (diatoms and Aureococcus) and nonphotosynthetic (Phytophthora) stramenopiles. Average gene density on pico-prymnesiophyte scaffolds was 74% (magenta line). (B) Venn diagram of pico-prymnesiophyte genes in relation to prasinophyte (green, Micromonas and Ostreococcus), diatom (beige), and Phytophthora (yellow) genes by BLASTP (e-value ≤1.0e−9). Numbers indicate gene counts in each Venn group (magenta letters), whereas pie charts show relative best BLAST proportions for overlapping groups. Some pico-prymnesiophyte genes (blue text) were not found in the other lineages. (C) Comparison of functional profiles of pico-prymnesiophyte–specific genes with those from each Venn group by high-level Gene Ontology (GO) molecular functions. Relative proportions are shown for each GO function within a Venn group such that each column represents 100%.

Genome size was calculated using multiple methods accommodating the composite nature of the sorted pico-prymnesiophyte population (SI Materials and Methods, Section 7). The first involved a model linking the size distribution of euKaryotic Orthologous Groups of proteins (KOG), allocation of functions across those families and total gene content for 12 protistan reference genomes. This rendered an average genome content of 12,711 (±1,145) genes (Fig. S2 A and B), such that the 1,624 pico-prymnesiophyte nuclear-encoded genes identified constituted 13% of those in a representative genome. Results were similar (11,600 total genes; SI Materials and Methods, Section 7) using a method based on counts of 132 near single-copy core genes in other eukaryotes. Diatom genome content is comparable, ≈10,000–14,000 genes (10), whereas the pico-prasinophytes contain 8,000 to just over 10,000 genes (9, 11).

Mosaic Gene Repertoires.

Evolutionary and functional aspects of chloroplast and nuclear genomes were analyzed using gene content. 16S rRNA genes revealed pico-prymnesiophyte chloroplast genome scaffolds; the largest (scaffold C19847), containing 45 protein-encoding genes among others (Tables S3 and S4), seemed to be from group 8 (SI Materials and Methods, Sections 5 and 6, and Figs. S1B and S3A). Phylogenetic analysis of 22 concatenated plastid genome-encoded genes conserved across all lineages placed this pico-prymnesiophyte within the Chromalveolata, between cryptophytes and stramenopiles, and directly sistered by E. huxleyi (SI Materials and Methods, Section 7, and Fig. S3B), the only published prymnesiophyte plastid genome (20). This placement corresponded to that for E. huxleyi in other plastid phylogenies (21), but with greater support. Nucleotide level comparison of C19847 with E. huxleyi showed large-scale rearrangements akin to the divergent diatoms (Fig. S3C). Gene-level synteny was relatively conserved with E. huxleyi (Fig. S3D).

In contrast, global analysis of the 1,624 predicted pico-prymnesiophyte nuclear-encoded genes revealed a distinctive evolutionary signature relative to plastid genome-encoded elements. Phylogenomic analyses of nuclear-encoded genes indicated that these phytoplankton are evolutionarily situated between the green-lineage and stramenopiles, with greater apparent affinity to the former. The gene repertoire shared a higher degree of overlap with prasinophytes (Fig. 3B). Even among pico-prymnesiophyte genes with homologs in both prasinophytes and stramenopiles, similarity was generally higher to prasinophytes. Of 352 phylogenetic trees constructed herein that contained at least one green-lineage organism and one stramenopile, the genetic distance between the pico-prymnesiophyte and the former was shorter twice as often (Fig. S4A). Across all trees, the mean relative genetic distance was 6.5% shorter between pico-prymnesiophytes and Archaeplastida, compared with stramenopiles, calling into question the current, largely plastid genome-based, phylogenetic placement of this lineage.

More than 75% of pico-prymnesiophyte genes assigned to KOGs were in the largest KOG families (top 20%), whereas for other marine phytoplankton this percentage was lower (SI Materials and Methods, Section 7). This high level of KOG redundancy reflected the mosaic nature of pico-prymnesiophyte gene repertoires. The functional KOG repertoire straddled prasinophytes and stramenopiles, such that several expansions in the metagenome seemed to be absent from one or both of these other lineages. Presence of more than one pico-prymnesiophyte taxon in the sort does not explain this redundancy, because it would require disproportionate sampling of the same KOGs, to the exclusion of others, from each pico-prymnesiophyte genome. Families with multiple representatives included nudix hydrolases and arylsulfatases, not found in prasinophytes, but present in metazoa and bacteria (arylsulfatases are also in stramenopiles) (Table S5). Polyketide synthases were also found and present in prasinophytes and bacteria but missing from diatoms.

The discontinuity in gene content could help explain puzzling ambiguities in prymnesiophyte evolution. The chloroplast genome would drive the relationship toward a red-lineage secondary endosymbiosis (Chromalveolata; Fig. S3B), whereas the nuclear genome retains features of a green host (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4A). Of pico-prymnesiophyte genes that appeared more similar to Archaeplastida than to stramenopiles, 55% were closer to streptophytes, particularly early diverging plants, suggesting a strong ancestral green-lineage influence in the prymnesiophyte host organism's gene pool; only 45% were closer to green algae (Fig. S4B). Alternatively, like diatoms (22), prymnesiophytes may have obtained green-lineage genes from an ancient cryptic endosymbiont. Although the paucity of eukaryotic phytoplankton genomes may influence results, nuclear-encoded marker genes from larger cultured prymnesiophytes also show strong green-lineage affiliations (3). We anticipate that E. huxleyi genome analysis will confirm that the mosaic gene repertoire reported here is a lineage-wide characteristic.

Functional Gene Repertoire.

Pico-prymnesiophyte nuclear-encoded genes also showed differences in functional composition (Fig. 3C). Although all transcription factor families recovered were also in Archaeplastida and stramenopiles, higher proportions of specific regulators were observed, such as chromatin remodeling genes (Tables S5 and S6), which play roles in meiosis and “lifestyle” changes. These included divergent SET-domain proteins and SNF2/helicases as chromatin remodeling factors (23). Distinct SUV39 subfamily members (SET) identified were not found in stramenopiles (Fig. S5A). This family is responsible for heterochromatin formation (23) and could enable control over invasive entities like transposons and viruses.

Other features corresponded to life in modern oceans, for example, a Ni-containing superoxide dismutase (Ni-SOD). SODs are vital to photosynthetic organisms, scavenging toxic superoxide radicals generated by multiple metabolic pathways including photosynthesis. Isoforms use different metals at the active site, influencing trace metal requirements (24). Presence of sodN, which encodes Ni-SOD, corresponds with absence of Fe-SOD–encoding genes in many marine bacterial genomes, and Ni-SOD seems to be more prevalent in open-ocean strains (25). This results in replacement of some cellular Fe demand with Ni, a valuable adaptation considering 10-fold higher Ni concentrations in oceanic waters (25). We identified putative sodN genes in the pico-prymnesiophyte metagenome, the four pico-prasinophyte genomes (see also ref. 9) and P. tricornutum (Fig. S5B). T. pseudonana did not seem to encode sodN, but rather a Fe-SOD, correlating with its coastal distribution and higher iron quotas than P. tricornutum (26). Fe-SOD–encoding genes were not found in the sodN-containing phytoplankton genomes. Presence of putative sodN genes in oceanic phytoplankton from three major eukaryotic lineages suggests that replacement of Fe-SOD with Ni-SOD may be a common adaptation to the lower availability of iron in modern oceans than in past times (27).

Several domains involved in uptake of large substrates, such as proteins and nucleic acids, as well as salvage of nucleosides, were represented more highly in the pico-prymnesiophyte metagenome (Fig. 3C). These could facilitate uptake of otherwise inaccessible nutrients. For example, a member of the amino acid/polyamine/organocation superfamily is a likely transporter for the nitrogen-rich guanine derivative xanthine, potentially important under nitrogen-limiting conditions. A plant-like putative acid phosphatase (Table S5), which likely cleaves intracellular orthophosphoric-monoesters to phosphate, could also be involved in nutrient scavenging, although this role is speculative. Overall, features of the metagenome suggest adaptations associated with survival in oligotrophic environments.

Environmental Importance.

Increased stratification and lower nutrient concentrations predicted under some climate-change scenarios are hypothesized to create conditions favoring picophytoplankton over larger species (11). However, questions remain regarding the ecological importance of pico-prymnesiophytes in today's conditions, against which physiological stressors and future changes can be assessed. To establish their roles, we developed a contextual metadataset for the pico-prymnesiophyte metagenome, including distributions at the subtropical North Atlantic sites (Fig. 2, Inset) by FISH. Biomass contributions were compared with the overall picophytoplankton community, specifically, other picoeukaryotes, Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus (SI Materials and Methods, Sections 2, 9, and 10).

Pico-prymnesiophyte contributions in the Sargasso Sea were roughly equivalent at the surface and deep chlorophyll maximum (DCM), representing 23% and 21% of picophytoplankton carbon, respectively. Two pico-prymnesiophyte size classes were evident, cells of 1.9 ± 0.4 × 2.1 ± 0.3 μm (n = 89) and 2.8 ± 0.6 × 3.4 ± 0.5 μm (n = 127) (Table S7). In the Florida Straits their contributions were typically higher in surface waters, although more nutrients were presumably available at the DCM (Fig. S6A). Here, 90% ± 9% and 87% ± 13% of prymnesiophytes were <3 μm, averaged over 1 y, at the surface and DCM, respectively. The direct-count–based biomass approach resulted in lower pico-prymnesiophyte DCM contributions than estimated by HPLC (Fig. S6B). However, these methods gave similar surface trends, supporting the HPLC-based inference that picoplanktonic taxa form most prymnesiophyte biomass in open-ocean surface waters (6, 12, 28).

Pico-prymnesiophyte specific growth rates showed that these tiny eukaryotes can grow rapidly, amplifying contributions to primary production. Rates were measured by the dilution method and direct counts (SI Materials and Methods, Section 11), which render growth rates close to in situ cell cycle–based rates for taxa amenable to the latter analysis (29, 30). Pico-prymnesiophyte growth rates in the Sargasso Sea were high at 15 m (1.12 d−1, r2 = 0.87, P < 0.07) and lower at 70 m (0.29 d−1, r2 = 0.73, P < 0.07). Prochlorococcus grew more slowly (0.63 d−1, r2 = 0.54, P < 0.01) than pico-prymnesiophytes at the surface, but faster (0.60 d−1, r2 = 0.61, P < 0.001) at depth. Because the pico-prymnesiophyte data constitute the first specific growth rates reported, for experimental validation, we compared Prochlorococcus growth rates with previous direct count-based rates from the same region and time of year, which were similar (0.52 d−1) (30).

We combined biomass with specific growth and mortality rates to estimate primary production. Despite lower pico-prymnesiophyte abundance, their combined greater cellular biomass and faster growth led to primary production levels comparable to Prochlorococcus at 15 m (1.1 and 1.8 μg C L−1 d−1, respectively; SI Materials and Methods, Section 11). Pico-prymnesiophyte primary production was almost 4-fold higher than that of all other picoeukaryotes (0.27 μg C L−1 d−1). Total primary production at the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS; Fig. 2, Inset) in mid-May, before our experiments, and just afterward, in mid-June, was 7.81 and 0.96 μg C L−1 d−1, respectively, at 20 m (31). Seasonal stratification developed during this period, leading to lower production by mid-June. Over a decade, BATS total primary production occasionally ranged up to 6 μg C L−1 d−1 at 20 m, but was typically 2–4 μg C L−1 d−1 each June; the pico-prymnesiophyte value constitutes 25–50% of that. Likewise, a flow cytometrically defined picoeukaryote population (73% ± 2% prymnesiophyte cells, over 20 stations), was recently shown to perform 25% ± 9% of primary production in the North East Atlantic, ranging up to 38% (32). Plastid-16S rRNA genes were evaluated at one station in that study and showed uncultured prymnesiophyte taxa, as found herein.

Global Contributions and Latitudinal Gradients.

Our results, taken with those from the North East Atlantic (32), point to significant pico-prymnesiophyte contributions in the subtropical North Atlantic. However, variations between oceans and latitudinal gradients translate to major biotic differences, and the respective communities will likely respond to change differently. To assess global surface biomass contributions by pico-prymnesiophytes we counted and sized cells in five biogeographical provinces, specifically subpolar (high-latitudes) and subtropical-temperate (midlatitudes) systems, as well as the tropics (low latitudes) (SI Materials and Methods, Sections 1, 2, 9, and 10, and Table S8).

Globally, pico-prymnesiophytes averaged 2.6 ± 1.8 μg C L−1 when the areal extent of each province was accounted for (Table 1). This amounted to ≈50% of that of Prochlorococcus (4.7 ± 2.1 μg C L−1), which was less evenly distributed and nearly absent from cold waters. The considerable biomass of pico-prymnesiophytes was again in part due to larger cell size than other picophytoplankton (6), and their contributions were less obvious by abundance alone (Table S8); Prochlorococcus, for instance, is orders of magnitude more abundant in low- and mid-latitudes but is also much smaller.

Table 1.

Average surface biomass of picophytoplankton groups in five biogeographical provinces

| Biomass (μg C L−1) | ||||||

| Latitude | Ocean area (× 1012 m2) | Samples (n) | Prochlorococcus | Synechococcus | “Non-prym” picoeukaryotes | Pico-prymnesiophytes |

| 60°–45°N | 13.22 | 8 | 0.1 (0.1) | 2.4 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.7) | 7.0 (4.7) |

| 45°–20°N | 47.18 | 24 | 3.7 (3.0) | 0.5 (0.5) | 1.0 (2.7) | 2.0 (1.5) |

| 20°N–20°S | 122.60 | 59 | 8.4 (2.8) | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.7) | 1.8 (0.9) |

| 20°–45°S | 75.35 | 19 | 3.1 (2.0) | 0.4 (0.6) | 3.7 (1.4) | 1.8 (0.9) |

| 45°–65°S | 48.69 | 11 | 0.3 (0.4) | 1.1 (1.9) | 3.9 (2.8) | 5.5 (4.9) |

Area varies over latitudinal zones owing to the influence of land masses; sample number is also shown, with values from sites sampled seasonally averaged and counted here as 1 sample (Table S8). Values in parenthesis reflect SDs.

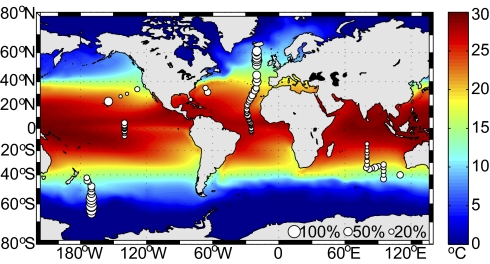

Biomass showed a strong latitudinal signal. In high latitudes, pico-prymnesiophytes dominated, comprising 50–56% of picophytoplankton biomass (Fig. 4, Table 1, and Table S8). Relative contributions in mid-latitudes were modified by variations in other groups. Pico-prymnesiophyte biomass per liter was maximal in the northern subpolar province, but the massive extent of the Southern Ocean, relatively unimpeded by land, rendered their greatest contributions to global biomass in the southern subpolar province.

Fig. 4.

Global surface biomass contributions of prymnesiophytes as percentage of total picophytoplankton carbon, represented by bubble size (scaling at lower right). Sea surface temperature represents 1° increments averaged monthly over 18 y; note differences in the five biogeographical provinces.

Pico-prymnesiophyte contributions were lowest in the tropics (1.8 μg C L−1), comprising approximately one fifth (21%) of Prochlorococcus biomass (Table 1). These in situ observations were at odds with a recent report suggesting that pico-prymnesiophytes are more important than Prochlorococcus in low latitudes, based on an algorithm relating satellite surface Chl to prymnesiophyte pigments and their contribution to total Chl (15). Validation (of ref. 15) would result in major reevaluation of tropical systems where the streamlined genome, small size, and low nutrient quotas of Prochlorococcus seem highly advantageous given extended periods of stratification (see, e.g., ref. 17). The significant discrepancy with our results may stem from issues surrounding the algorithm-based approach used in ref. 15, such as (i) the fact that other lineages can contain the prymnesiophyte-indicative marker pigment (28, 33) (SI Materials and Methods, Section 8), (ii) a variable relationship between a specific pigment content and surface Chl, or (iii) not partitioning contributions by organism size and the fact that HPLC samples are not size-fractionated. Furthermore, our tropical surface direct-count–based Prochlorococcus biomass data corresponded well with that from HPLC (28, 34), which, for Prochlorococcus, is less prone to such caveats.

Pico-prymnesiophytes seem to be highly successful and show signs of optimization to open-ocean conditions. Features within the metagenome remain difficult to relate to niche differentiation given 37% genes of unknown function, similar to many genomes. This lack of functional understanding is perhaps the greatest impediment to connecting genomes to organism physiology and response. The research herein positions us to explore the function of such genes in situ.

Conclusions

Soft-bodied prymnesiophytes survived the K/T boundary mass extinctions (16), indicating that taxa akin to those analyzed herein were resilient to perturbation. Surface water warming has now been correlated with increases of picophytoplankton in the Arctic Ocean (35) and will presumably impact lower latitudes. However, the success of small prymnesiophytes and their contributions in future times are linked to evolutionary history and genetic makeup, as well as the rate and extent of perturbations experienced.

Our results, showing genomic features of pico-prymnesiophytes, their rapid growth and significant global contributions, provide several key advancements. Although pico-prymnesiophytes are clearly diverse, aspects of composition, potential streamlining, and functional attributes revealed by targeted metagenomics provide insights into their evolutionary success. Together with data on prasinophytes and stramenopiles (10, 11), our analysis of the pico-prymnesiophyte metagenome indicates that mixed-lineage gene repertoires are a transcendent property of successful phytoplankton in modern oceans, not a rare feature. These mosaic gene repertoires seem to be compositionally distinct for each lineage, influenced by disparate sources of the tree of life, or differential gene loss from an ancestor, and presumably factors driving niche differentiation. Furthermore, the complexity of marine microbial communities makes it difficult to determine taxa critical to ecosystem processes and global biogeochemical models; our work highlights the need to prioritize pico-prymnesiophytes. Finally, it opens the door for research on the physiology and response capabilities of uncultivated members of this ancient primary producer lineage.

Materials and Methods

Methods details are in SI Materials and Methods. Samples were from the North, Equatorial, and South Atlantic, the North, Equatorial, and West Pacific, and the Indian Ocean(s). 18S rDNA clone libraries (14) were constructed from subtropical Atlantic and North West Pacific size-fractionated samples, or from cells sorted by flow cytometry.

Approximately 300 cells from target populations in the subtropical North Atlantic were sorted by flow cytometry. DNA from two populations was amplified by multiple displacement amplification (19) and used for PCR-based clone libraries and, for one sample, metagenomic sequencing. Metagenomic data were assembled in a two-step high-stringency process and only scaffolds resulting from the second stage considered further. Scaffolds were screened by phylogenomic methods using predicted genes and a database containing, among others, 46 eukaryotic genomes including 10 phytoplankton and 2 additional protistan stramenopile genomes. Comparative gene analyses with E. huxleyi are prohibited and were not performed. Pico-prymnesiophyte predicted proteins were characterized by profiling and genome-size estimate methods. Chloroplast scaffolds were manually selected and annotated.

Microscopy was used with a prymnesiophyte-specific FISH probe (36) to count and size cells. For some cruises identification was by chloroplast arrangement, flagellar characteristics, and occasional presence of a haptonema; no significant difference (t test, P = 0.43) was detected for Atlantic data from 25° to 35° N (FISH: 500 ± 61 mL−1, n = 26; characteristics-based: 593 ± 108 mL−1, n = 12). Other picophytoplankton groups were enumerated by flow cytometry (37). Biovolume was calculated from cell size for pico-prymnesiophytes and biomass determined using an established biovolume-based carbon conversion factor, also used for other picophytoplankton groups (38) (Table S7). Dilution experiments were according to (28, 30) and counts by FISH and flow cytometry. HPLC data were analyzed according to ref. 39.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the captains and crews of research vessels Discoverer, Endeavor, Ka'imimoana, Malcolm Baldridge, Oceanus, Walton Smith, and Western Flyer; cruise participants, especially F. Not; J. Heidelberg, R. Gausling, and G. Weinstock for 18S rDNA sequencing; M. Kogut, S. Giovannoni, and R. Gausling for edits; and J. Eisen. Sequencing was under DE-AC02-05CH11231, by a Department of Energy Community Sequencing Program award to A.Z.W. and J. Eisen. Support was in part by DE-FC02-02ER63453, NSF OCE-0722374, and NSF-MCB-0732448 (to A.E.A.); a National Human Genomic Research Institute, National Institutes of Health grant (to R.S.L.); National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and David and Lucile Packard Foundation (DLPF) grants (F.P.C.); NSF-OCE-0241740 (to B.J.B.); and major funding by NSF-OCE-0836721, the DLPF, and a Moore Foundation Young Investigator Award as well as Moore 1668 (to A.Z.W.). Author contribution details are given in SI Materials and Methods, Section 12.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. HM581528–HM581638 and HM565909–HM565914). Other scaffolds with predicted genes from this Whole Genome Shotgun/454 project have been deposited at DNA Data Bank of Japan/European Molecular Biology Laboratory/GenBank under the accession no. AEAR00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, AEAR01000000.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1001665107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Field CB, Behrenfeld MJ, Randerson JT, Falkowski P. Primary production of the biosphere: Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science. 1998;281:237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chisholm SW, et al. Prochlorococcus marinus nov gen nov sp: An oxyphototrophic marine prokaryote containing divinyl chlorophyll a and b. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hampl V, et al. Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Excavata and resolve relationships among eukaryotic “supergroups”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3859–3864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807880106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keeling PJ, et al. The tree of eukaryotes. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm SW. In: Primary Production and Biogeochemical Cycles in the Sea. Falkowski PG, Woodhead AD, editors. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worden AZ, Not F. In: Microbial Ecology of the Oceans. 2nd Ed. Kirchman DL, editor. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. p. 594. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaulot D, Eikrem W, Viprey M, Moreau H. The diversity of small eukaryotic phytoplankton (< or =3 microm) in marine ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:795–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raven JA. Small is beautiful: the picophytoplankton. Funct Ecol. 1998;12:503–513. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palenik B, et al. The tiny eukaryote Ostreococcus provides genomic insights into the paradox of plankton speciation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7705–7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611046104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowler C, Vardi A, Allen AE. Oceanographic and biogeochemical insights from diatom genomes. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2010;2:429–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worden AZ, et al. Green evolution and dynamic adaptations revealed by genomes of the marine picoeukaryotes Micromonas. Science. 2009;324:268–272. doi: 10.1126/science.1167222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackey D, Blanchot J, Higgins H, Neveux J. Phytoplankton abundances and community structure in the equatorial Pacific. Deep-Sea Res Pt I. 2002;49:2561–2582. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon-van der Staay S, et al. Abundance and diversity of prymnesiophytes in the picoplankton community from the equatorial Pacific Ocean inferred from 18S rDNA sequences. Limnol Oceanogr. 2000;45:98–109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Not F, Gausling R, Azam F, Heidelberg JF, Worden AZ. Vertical distribution of picoeukaryotic diversity in the Sargasso Sea. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:1233–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, et al. Extreme diversity in noncalcifying haptophytes explains a major pigment paradox in open oceans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12803–12808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905841106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medlin L, Saez AG, Young JR. A molecular clock for coccolithophores and implications for selectivity of phytoplankton extinctions across the K/T boundary. Mar Micropaleontol. 2008;67:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLong EF, Karl DM. Genomic perspectives in microbial oceanography. Nature. 2005;437:336–342. doi: 10.1038/nature04157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zehr JP, et al. Globally distributed uncultivated oceanic N2-fixing cyanobacteria lack oxygenic photosystem II. Science. 2008;322:1110–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1165340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean FB, et al. Comprehensive human genome amplification using multiple displacement amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082089499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sánchez Puerta MV, Bachvaroff TR, Delwiche CF. The complete plastid genome sequence of the haptophyte Emiliania huxleyi: a comparison to other plastid genomes. DNA Res. 2005;12:151–156. doi: 10.1093/dnares/12.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Corguillé G, et al. Plastid genomes of two brown algae, Ectocarpus siliculosus and Fucus vesiculosus: further insights on the evolution of red-algal derived plastids. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moustafa A, et al. Genomic footprints of a cryptic plastid endosymbiosis in diatoms. Science. 2009;324:1724–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.1172983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillon SC, Zhang X, Trievel RC, Cheng XD. The SET-domain protein superfamily: Protein lysine methyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2005;6:227. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe-Simon F, Starovoytov V, Reinfelder JR, Schofield O, Falkowski PG. Localization and role of manganese superoxide dismutase in a marine diatom. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1701–1709. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.088963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupont CL, Buck KN, Palenik B, Barbeau K. Nickel utilization in phytoplankton assemblages from contrasting oceanic regimes. Deep-Sea Res Pt I. 2010;57:553–566. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kustka AB, Allen AE, Morel FMM. Sequence analysis and transcriptional regulation of iron aquisition genes in two marine diatoms. J Phycol. 2006;43:715–729. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falkowski PG, et al. The evolution of modern eukaryotic phytoplankton. Science. 2004;305:354–360. doi: 10.1126/science.1095964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landry MR, et al. Phytoplankton growth and microzooplankton grazing in high-nutrient, low-chlorophyll waters of the equatorial Pacific: Community and taxon-specific rate assessments from pigment and flow cytometric analyses. J Geophys Res-Oceans. 2003;108:8142–8155. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landry MR. In: Handbook of Methods in Aquatic Microbial Ecology. Kemp PF, Sherr BF, Sherr EB, Cole JJ, editors. Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers; 1993. pp. 715–722. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Worden AZ, Binder BJ. Application of dilution experiments for measuring growth and mortality rates among Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus populations in oligotrophic environments. Aquat Microb Ecol. 2003;30:159–174. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lomas MW, et al. Increased ocean carbon export in the Sargasso Sea linked to climate variability is countered by its enhanced mesopelagic attenuation. Biogeosciences. 2010;7:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jardillier L, Zubkov MV, Pearman J, Scanlan DJ. Significant CO2 fixation by small prymnesiophytes in the subtropical and tropical northeast Atlantic Ocean. ISME J. 2010 doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.36. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carreto JI, Seguel M, Montoya NG, Clement A, Carignan MO. Pigment of the ichthyotoxic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium sp. from a massive bloom in southern Chile. J Plankton Res. 2001;23:1171–1175. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Letelier RM, et al. Temporal variability of phytoplankton community structure based on pigment analysis. Limnol Oceanogr. 1993;38:1420–1437. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li WKW, McLaughlin FA, Lovejoy C, Carmack EC. Smallest algae thrive as the Arctic Ocean freshens. Science. 2009;326:539. doi: 10.1126/science.1179798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon N, et al. Oligonucleotide probes for the identification of three algal groups by dot blot and fluorescent whole-cell hybridization. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2000;47:76–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2000.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buck KR, Chavez FP, Campbell L. Basin-wide distributions of living carbon components and the inverted trophic pyramid of the central gyre of the North Atlantic Ocean, summer 1993. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1996;10:283–298. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Worden AZ, Nolan JK, Palenik B. Assessing the dynamics and ecology of marine picophytoplankton: The importance of the eukaryotic component. Limnol Oceanogr. 2004;49:168–179. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright SW, et al. Composition and significance of picophytoplankton in Antarctic waters. Polar Biol. 2009;32:797–808. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi XL, Marie D, Jardillier L, Scanlan DJ, Vaulot D. Groups without cultured representatives dominate eukaryotic picophytoplankton in the oligotrophic South East Pacific Ocean. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.