Abstract

Objective:

High rates of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders have been noted in South Africa. Although a number of risk factors for alcohol use and abuse/dependence have been identified, there is a lack of information regarding risk factors for progression through the different stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Our aim was to examine sociodemographic predictors of transition across stages of alcohol use, abuse and dependence (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition), and remission in the South African population.

Method:

A national probability sample of 4,315 adult South Africans was administered Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Results:

We found high rates of transition from regular alcohol use to abuse but low rates from alcohol abuse to dependence. All stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders were more common in younger than in older respondents at comparable time points. Younger age (below 50), male gender, lower education, and having been a student were all associated with ever using alcohol, but only male gender was associated with the transition to regular use and abuse. Furthermore, younger age and late age at onset of alcohol abuse were associated with remission from abuse.

Conclusions:

The importance of socio-demographic predictors appears to vary across stages of alcohol use and could be used to guide the precision of intervention strategies.

The south african Demographic and Health Survey in 1998 found that 45% of men and 17% of women were current drinkers (Parry et al., 2005) and the more recent South African Stress and Health (SASH) study found that alcohol was used by 38.7% of participants (van Heerden et al., 2009). Although these rates are low compared with a number of other countries, such as the United States and Australia (McBride et al., 2009), the consumption of alcohol per drinker in South Africa has been reported to be among the highest in the world (Rehm et al., 2003). Risky drinking has been noted to be 22.0% (37.4% of men and 5.0%-10.7% of women) in studies in rural populations (Peltzer, 2006; Peltzer et al., 2004), with 9.2% of men and 0.3% of women meeting criteria for probable alcohol dependence on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Peltzer, 2006).

Alcohol harm accounted for an estimated 7.1% of all deaths and 7.0% of total disability-adjusted life years in the South African National Burden of Disease Study for 2000, and alcohol-use disorders ranked first (44.6%) in terms of alcohol-attributable disability (Schneider et al., 2007). In a study of the association of acute alcohol use and risk of nonfatal injury in 16 countries, South Africa had the highest relative risk, with 46.4% of injured patients who were analyzed reporting drinking in the previous 6 hours (Borges et al., 2006).

These data underscore the importance of identifying and addressing risk factors for alcohol abuse and dependence. A number of risk factors for alcohol use and abuse in South Africa have been identified. Parry et al. (2005) found that White males and those residing in an urban area were more likely to use alcohol. Lower socioeconomic status, no school education in women, and being older than 25 years of age were associated with alcohol problems. Peltzer (2006) found that male gender and being single, divorced, or widowed predicted harmful drinking, and Ward et al. (2008) found that male gender, younger age (men), no religious involvement, employment, some high school education (compared with less [e.g., no high school] or more [e.g., completing high school] education), and higher stress were associated with hazardous alcohol use. The apparent contradiction in socio-economic status and employment findings may be because, in a low- to middle-income country such as South Africa, the poorest segments of society may be unable to purchase alcohol. The rate of consumption would then increase in those who are earning at least some money.

There is a paucity of information regarding risk factors for progression through the different stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. A report by Grant and Dawson (1997) of the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey in the United States found that, although Whites were significantly more likely than either Blacks or Hispanics to use alcohol and more likely than Blacks to develop dependence, once dependence occurred, Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to persist in their dependence. The married, wealthiest, and most highly educated respondents were more likely to use alcohol but less likely to become dependent or persist in their dependence than respondents who were never married, separated, divorced, or widowed; respondents with lower incomes; and those with less education, respectively. Last, those living in urban areas were more likely to use alcohol but were no more at risk than those living in rural areas to develop dependence or persist in their dependence.

A number of studies in high-income countries have indicated a strong association between age at onset of drinking and patterns of drinking as well as alcohol-related problems (e.g., Ehlers et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2001; Hasin and Glick, 1992; Hingson et al., 2006; Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Pitkanen et al., 2005). Being male; being unmarried, divorced, or separated; not having a high school degree; and being of younger age have been found to increase the risk of alcohol abuse and dependence (Ehlers et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2001; Hasin and Glick, 1992; Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Pitkanen et al., 2005). Psychiatric disorders (Dawson et al., 2005; Ehlers et al., 2006) also have been identified as risk factors. Remission of alcohol-use disorders has been associated with being married, less severe dependence, increased age, and female gender (Dawson et al., 2005). There are few data on the above from developing countries such as South Africa, as well as few data on risk factors for transitions across the different stages of alcohol-use disorders.

The SASH study, the first nationally representative study of mental health disorders in Africa, provided an opportunity to address the question of which risk factors are most prominent at each stage of development of these disorders. Here, we aim to establish socio-demographic predictors of transition across stages of alcohol use, abuse, dependence, and remission in the South African population.

Method

Participants and procedures

The SASH study was a national probability sample of 4,351 adult South Africans living in both households and hostel quarters (Stein et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2004). Hostel quarters were included to maximize coverage of young working men. Individuals in institutions or in the military were not included. The sample was selected using a three-stage probability sample design. The first stage involved the selection of stratified primary sample areas based on the 2001 South African census enumeration areas. The second stage involved the sampling of housing units from each enumeration area, and the third stage was the random selection of one adult respondent from each housing unit. SASH study interviewers were extensively trained in centralized group sessions lasting 1 week. The interviews were conducted face-to-face in seven different languages: English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, Northern Sotho, Southern Sotho, and Tswana. Interviews lasted an average of 3.5 hours, with some requiring more than one visit to complete. Data were collected between January 2002 and June 2004. Field interviewers made up to three attempts to contact each respondent, and the overall response rate was 85.5%. The SASH data set includes person-level analysis weights that incorporate sample selection, nonresponse, and poststratifi-cation factors (Williams et al., 2004, 2008). This weight was used in computing estimates of descriptive statistics for the survey population (e.g., estimates of population means and proportions) and for estimation of analytical statistics (e.g., regression coefficients) required in modeling relationships among variables in the survey population.

Diagnostic assessment

Alcohol use, abuse, and dependence were assessed using Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Kessler and Ustun, 2004). This is a fully structured interview that generates diagnoses according to the definitions and criteria of both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems-10th Revision (World Health Organization, 2005) diagnostic systems. DSM-IV criteria are used in the current report.

All respondents were screened for alcohol use by being asked the age at which they first drank an alcoholic beverage. If the respondent reported ever drinking, drinking behavior and criteria for DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence were assessed. Alcohol variables examined in the present analyses included variables for six stages of alcohol use (never use, ever use, regular use [defined as drinking at least 12 drinks in a year], abuse, dependence, and remission) as well as variables that represent the conditional use of alcohol in three stages (regular use among alcohol users, alcohol abuse among regular alcohol users, alcohol dependence among alcohol abusers). Remission was defined as the cessation of alcohol use and the absence of any symptoms for at least 2 years before the interview.

Age-at-onset and transition variables

A number of age-at-onset variables were created, including age at onset of alcohol use ("How old were you the very first time you ever drank an alcoholic beverage?") and age at onset of regular drinking ("How old were you when you first started drinking at least 12 drinks in a year?"). The onset of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence was defined as the ages at which any symptoms of abuse or dependence first occurred ("How old were you the very first time you had any of these problems?"). A fourth age-at-onset variable determined the most recent age at having any symptom among respondents with a history of remitted alcohol abuse or dependence. Additional variables were created to represent the speed of transition between onset of first use and onset of first regular use among lifetime regular users as well as the speed of transition between onset of first regular alcohol use and onset of abuse. Both of these speed-of-transition variables were calculated by taking the age at onset of the earlier stage of alcohol use and subtracting it from the age at onset of the later stage.

Sociodemographic correlates

Sociodemographic correlates include age (defined by age at interview in categories 18-34 years, 35-49 years, 50-64 years, and ≥65 years), gender, completed years of education (low, low-average, average-high, and high), student status (student vs. nonstudent), and marital status (never married, previously married, and married/cohabitating). Information collected for education, student status, and marital status was used to treat these variables as time-varying covariates in the survival analyses. Because information on income was collected only at the time of interview (unlike the other variables, covering every year of the person's life), it was not included as a covariate in the survival models.

Statistical analysis

The relationship between socio-demographic predictors and the six stages of alcohol use was determined by cross-tabulation analysis. Estimated projected age-at-onset distributions of the cumulative lifetime probability of alcohol use, regular use, abuse, and dependence as of age 65 were obtained by the actuarial method implemented in PROC LIFETEST in SAS (Version 9.1.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary,NC).

Predictors of transitions across the six stages were examined using discrete-time survival analysis using the logit function with person-year as the unit of analysis. Standard errors and significant tests were estimated using the Taylor series linearization method implemented in SUDAAN (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) to adjust for design effects. Multivariate significance tests were made with Wald chi-square tests using Taylor series design-based coefficient variance-covariance matrices. The person-year data array used in the transition from never use to first use includes all years in the life of the respondents before and including their age at having their first drink. The person-year data array for the following three stages of analysis (ever use to regular use, regular use to abuse, abuse to dependence) included all years beginning with the year after the earlier transition and continuing through to the year of onset of the next transition or, for respondents who never made the next transition, through to their age at interview. For the transition from abuse or dependence to remission, the person-year data array was defined as all years beginning in the year after the first onset of abuse (in the case of lifetime abusers who never developed dependence) or dependence and continuing either for 2 years after the most recent occurrence of any abuse or dependence symptom (which was the operational definition of remission) or until 1 year before age at interview (in the case of respondents whose most recent abuse or dependence symptoms occurred more recently than 2 years before interview, who were defined as not remitted).

All survival equations included predictors for age at interview, person-year (time varying), gender, education (time varying), student status (time varying), and marital status (time varying). In addition, the equations for later stages included predictors defined by information about timing of earlier stages. For example, the analysis of the transition between regular use and abuse includes predictors for age at onset of use, age at onset of regular use, and speed of transition between first use and first regular use. However, any two of the latter three variables perfectly defines the third, making it impossible to include all three in any one prediction equation. This problem was addressed by estimating a series of three equations, each with two of these three variables as predictors, and then choosing the most parsimonious model. The same process was applied in all equations that included information about multiple earlier transitions.

Results

Prevalence of lifetime alcohol use, abuse, and dependence

Of the total sample, 41.3% (SE = 1.1) of respondents reported that they had had at least a sip of alcohol in their life, 34.0% (SE =1.1) reported using alcohol regularly at some time in their life, 11.4% (SE = 0.8) met criteria for alcohol abuse at some time in their life, and 2.6% (SE = 0.4) met criteria for alcohol dependence at some point in their lives.

Successive pairs of these prevalence estimates can be divided by each other to compute transition probabilities, with 82.3% (SE = 1.1) of ever users making the transition to regular use, 33.4% (SE = 2.1) of regular users going on to develop alcohol abuse, and 22.8% (SE = 2.6) of those with a history of alcohol abuse making the transition to alcohol dependence.

In the last 12 months, only 4.9% (SE = 0.5) and 1.2% (SE = 0.2) of the sample met criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence, respectively. This suggests that 43.0% of participants with alcohol abuse and 46.2% of those with dependence were in remission from these disorders.

Age at onset of alcohol use, abuse, and dependence

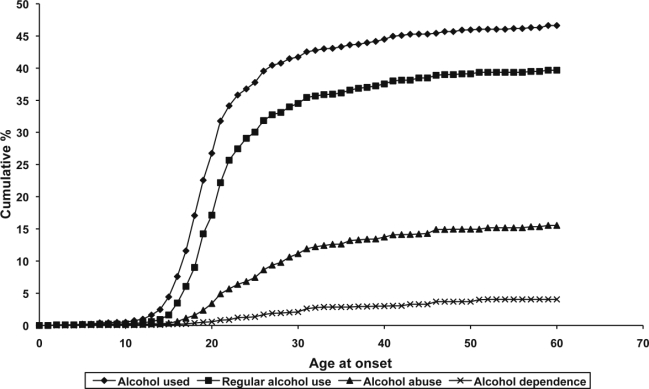

The onset of each stage of alcohol use shows the greatest increase between the early teens and mid-20s, with half of all lifetime users and regular users having begun use by age 20, and more than half of all projected lifetime abusers and people with lifetime dependence meeting criteria for these disorders by age 25 (Figure 1). The mean age at onset of first ever using alcohol was 19.9 years (SD = 0.16) and of regular use of alcohol was 21.1 years (SD = 0.18). The mean age at onset of alcohol abuse or dependence was 23.8 years (SD = 0.34).

Figure 1.

Age at onset of alcohol use, regular use, abuse, and dependence of each user

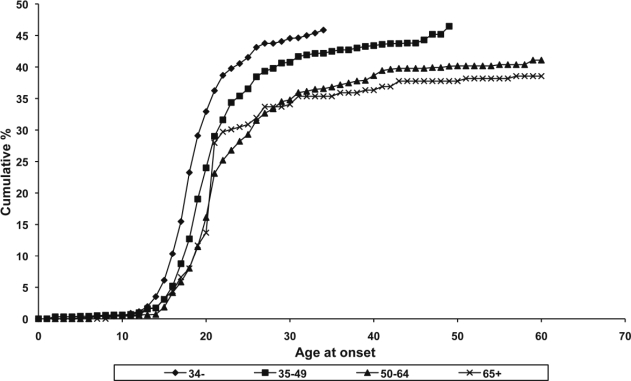

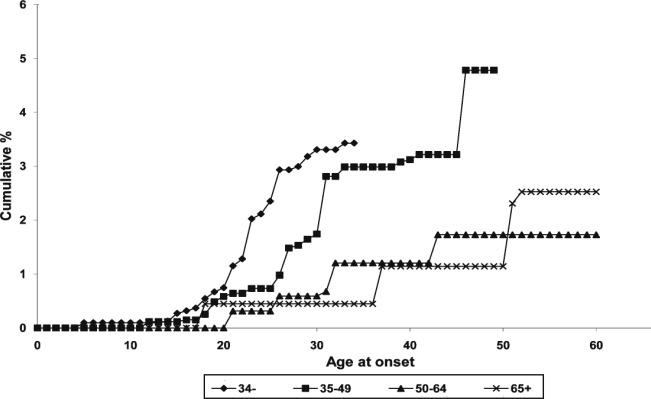

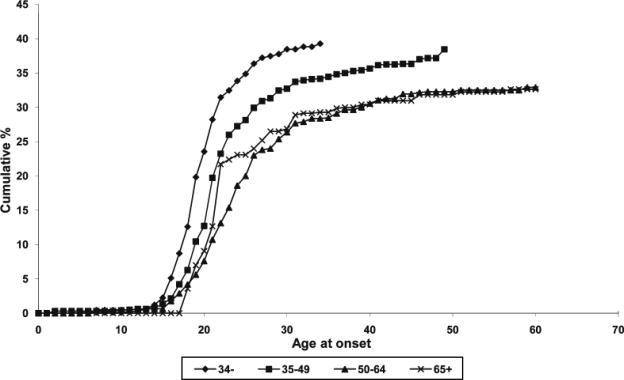

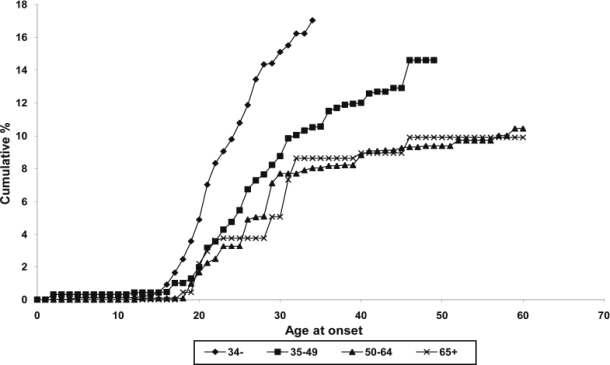

Age effects

All stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders were more common in younger than in older respondents at comparable points in their lives (Figures 2-5) with the exception of the 65-or-older age group, who were more likely than the 50- to 64-year-old age group to have used alcohol (regularly or just tried it) in their early 20s. The 65-or-older age group was also more likely than the 50- to 64-year-old group to have met criteria for alcohol abuse in their early 30s and late 40s and to have met criteria for alcohol dependence in their 50s.

Figure 2.

Age at onset of alcohol use, by cohort

Figure 5.

Age at onset of alcohol dependence, by cohort

Figure 3.

Age at onset of regular alcohol use, by cohort

Figure 4.

Age at onset of alcohol abuse, by cohort

Sociodemographic predictors of alcohol use, abuse, and dependence

Onset of ever having used alcohol was associated with being younger than 50 years of age, being male, having attained lower levels of education, and having been a student (Table 1). Transition from ever use to regular use and from regular use to abuse was associated both with being male and with the reporting of early age at onset of first alcohol use. There were no predictors of alcohol dependence among alcohol abusers.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic risk factors for first onset of alcohol-related outcomes

| Socio-demographic | Ever used alcohol | Regular use among alcohol users | Alcohol abuse among regular users | Alcohol dependence among abusers | ||||

| Cohort | ||||||||

| 18–34, OR [CI] | 3.16* | [2.19, 4.56] | 1.26 | [0.92, 1.72] | 1.42 | [0.74, 2.71] | 1.07 | [0.41, 2.80] |

| 35–49, OR [CI] | 2.07* | [1.51,2.83] | 1.08 | [0.79, 1.48] | 1.12 | [0.60, 2.08] | 1.20 | [0.40, 3.64] |

| 50–64, OR [CI] | 1.36 | [0.95, 1.95] | 0.85 | [0.61, 1.18] | 0.95 | [0.48, 1.85] | 0.78 | [0.20, 3.01] |

| ≥65, reference | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| χ23 [p] | 83.2** | [0.000] | 12.6** | [0.005] | 5.4 | [0.143] | 0.9 | [0.826] |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female, OR [CI] | 0.31* | [0.28, 0.36] | 0.60* | [0.51, 0.69] | 0.73* | [0.56, 0.94] | 1.19 | [0.67, 2.11] |

| Male, reference | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| χ2i [p] | 293.8** | [0.000] | 47.1** | [0.000] | 6.1** | [0.014] | 0.4 | [0.551] |

| Education | ||||||||

| Student, OR [CI] | 0.66* | [0.44, 0.98] | 0.90 | [0.59, 1.38] | 1.03 | [0.65, 1.63] | 1.90 | [0.66, 5.52] |

| Low, OR [CI] | 0.50* | [1.01, 2.22] | 0.92 | [0.54, 1.58] | 0.80 | [0.43, 1.51] | 0.59 | [0.14, 2.44] |

| Low-average, OR [CI] | 1.90* | [0.28, 2.80] | 0.74 | [0.49, 1.12] | 0.95 | [0.68, 1.32] | 1.02 | [0.38, 2.71] |

| Average-high, OR [CI] | 2.10* | [1.42, 3.10] | 0.95 | [0.62, 1.74] | 1.01 | [0.72, 1.43] | 1.27 | [0.58, 2.78] |

| High, reference | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| χ24[p] | 145.2** | [0.000] | 7.3 | [0.122] | 0.6 | [0.962] | 2.5 | [0.644] |

| Additional predictors | ||||||||

| Age at first use, OR [CI] | 1.03* | [1.02, 1.05] | 0.96* | [0.93, 1.00] | ||||

Notes: A dash (–) indicates that it was not executed because of small sample size (n < 30). Results are based on multivariate discrete-time survival model with person-year as the unit of analysis; see the text for a description. All confidence intervals (CIs) are 95% CIs. OR = odds ratio.

OR significant at the .05 level, two-sided test;

significant at the .01 level, two-sided test.

Sociodemographic predictors of remission from abuse and dependence

Remission from alcohol abuse without dependence was associated with being younger than age 35 years and a late age at onset of abuse (Table 2). There were no predictors of remission from alcohol dependence.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic factors for recovery of alcohol-related outcomes

| Socio-demographic | Recovery from alcohol dependence | Recovery from alcohol abuse without dependence | ||

| Cohort | ||||

| 18–34, OR [CI] | 1.25 | [0.40, 3.91] | 5.45* | [2.16, 13.80] |

| 35–49, OR [CI] | 0.48 | [0.19, 1.22] | 1.62 | [0.70, 3.77] |

| 50–64, OR [CI] | 1.31 | [0.51, 3.34] | 0.80 | [0.30, 2.16] |

| ≥65, reference | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| 723[p] | 9.6** | [0.022] | 20.2** | [0.000] |

| Sex | ||||

| Female, OR [CI] | 0.98 | [0.49, 1.98] | 1.08 | [0.70, 1.68] |

| Male, reference | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| 721[p] | 0.0 | [0.958] | 0.1 | [0.715] |

| Education | ||||

| Student, OR [CI] | 0.53 | [0.04, 7.24] | 1.23 | [0.41,3.71] |

| Low, OR [CI] | 0.38 | [0.05, 2.93] | 1.11 | [0.39,3.13] |

| Low-average, OR [CI] | 1.15 | [0.24, 5.49] | 1.52 | [0.67, 3.44] |

| Average-high, OR [CI] | 1.78 | [0.51, 6.17] | 1.43 | [0.73, 2.80] |

| High, reference | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| 724[p] | 6.0 | [0.202] | 2.1 | [0.724] |

| Additional predictors | ||||

| Age at onset of alcohol abuse, OR [CI] | 1.03 | [0.98, 1.09] | 1.07* | [1.04, 1.11] |

Notes: A dash (–) indicates that it was not executed because of small sample size (n < 30). Results are based on multivariate discrete-time survival model with person-year as the unit of analysis; see the text for a description. All confidence intervals (CIs) are 95% CIs. OR = odds ratio.

OR significant at the .05 level, two-sided test;

significant at the .01 level, two-sided test.

Discussion

Less than half the sample (41.3%) had ever tried alcohol in their lives, and just above one third (34.0%) reported a history of regular use. More than 10% (11.4%) had met criteria for alcohol abuse, and 2.6% met criteria for alcohol dependence. Although these rates are consistent with previous data from South Africa, they are much lower (except for alcohol dependence, which was only slightly lower) than rates from the developed world, for example, in data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study (Kalaydjian et al., 2009).

We found high rates of transition from regular alcohol use to abuse but low rates from alcohol abuse to dependence. Indeed, when compared with the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study in the United States (Kalaydjian et al., 2009), almost twice the percentage of regular drinkers in our survey went on to develop alcohol abuse, but only half the percentage made the transition to dependence. That the same methodology was used in both studies suggests that this is a real difference and did not arise because the CIDI is unable to categorize alcohol dependence without alcohol abuse. This low rate of alcohol dependence could be explained by the fact that there is less expendable salary in South Africa and thus it is harder to afford dependence. That all stages of alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders were more common in younger than in older respondents at comparable time points suggests a worsening of alcohol problems in younger generations and is consistent with findings in other countries (Degenhardt et al., 2008).

The importance of sociodemographic predictors varied across stages of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Younger age (below age 50), male gender, lower education, and having been a student were all associated with ever using alcohol. This is consistent with a number of other studies (Ehlers et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2001; Hasin and Glick, 1992; Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Pitkanen et al., 2005). However, in contrast to findings from these studies, only male gender was associated with the transition to regular use and abuse, and none of these variables was associated with dependence. In accordance with previous literature, early age at onset of first alcohol use was also associated with alcohol abuse (Ehlers et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2001; Hasin and Glick, 1992; Hingson et al., 2006; Pitkanen et al., 2005) but not dependence.

We found younger age and late age at onset of alcohol abuse to be associated with remission from abuse. Although these findings are not consistent with all other studies (e.g., Dawson et al., 2005), some authors have suggested that younger respondents may be more likely to remit for a number of reasons, including changes in lifestyle, factors related to work or education, transition to other drugs, and maturity (Kalaydjian et al., 2009). Extrapolating from research demonstrating early age at onset as a marker of disorder severity, it is likely that a later age at onset of abuse would increase the chance of remission from abuse (Kalaydjian et al., 2009).

Twin studies (Sartor et al., 2008; Whitfield et al., 2004) have demonstrated that genetic factors have a greater influence on the development and persistence of alcohol dependence than on the earlier stages of alcohol use. Thus, environmental, cultural, and social variables may play a greater role in the early stages of use. This may help explain the variability of risk indicators at the various stages and why there are more socio-demographic risk indicators of alcohol use than of alcohol abuse and dependence.

There are several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting these results. First, the SASH study was a retrospective survey; thus, there may have been potential recall problems, because age at first use and at onset of problems may have occurred many years ago and may not have been remembered accurately. Second, social desirability may have influenced responses in terms of underreporting and the ages at which use, abuse, and dependence occurred. Third, only a limited number of socio-demographic variables were considered here; and fourth, potential confounding factors that may influence transition–such as genetic factors, environmental stressors, and presence of psychiatric disorders–were not considered. A fifth limitation is the inability of the CIDI to discriminate alcohol dependence without abuse. This may have led to reduced prevalence estimates for dependence as well as an inability to distinguish between age at onset of alcohol abuse and age at onset of alcohol dependence. Last, low power may have contributed to the absence of significant associations between demographic factors and any other drinking stages besides age at onset.

Despite these limitations, these findings are novel in the context of a developing country. They emphasize the early onset of drinking (particularly in young, uneducated men) and the very high transition rate to abuse (particularly in men). Such findings could be used to guide the precision of intervention strategies aiming to prevent onset of drinking and to prevent transition to problematic drinking. Prospective longitudinal studies of drinking as well as prevention strategies that attempt to delay the age at onset of alcohol use are called for.

Acknowledgment

We thank the World Health Organization World Mental Health staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis.

Footnotes

The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. This research was supported by the U. S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant R01MH070884; the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; the Pfizer Foundation; U.S. Public Health Service grants R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01-DA016558; Fogarty International Center grant FIRCA R01-TW006481; the Pan American Health Organization; Eli Lilly and Company; Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The SASH study was funded by NIMH grant R01-MH059575 and the National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. Dan J. Stein and Soraya Seedat are also supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at: www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Cherpitel C, Orozco R, Bond J, Ye Y, Macdonald, S, Poznyak V. Acute alcohol use and the risk of non-fatal injury in sixteen countries. Addiction. 2006;101:993–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001-2002. Addiction. 2005;100:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu W-T, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Anthony JC, Angermeyer, M, Wells E. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Slutske WS, Gilder DA, Lau P, Wilhelmsen KC. Age at first intoxication and alcohol use disorders in Southwest California Indians. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1856–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: A 12-year follow-up. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Glick H. Severity of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence: United States, 1988. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:1725–1730. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaydjian A, Swendsen J, Chiu WT, Dierker L, Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Kessler R. Sociodemographic predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use, disorders, and remission in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride O, Teesson, Slade T, Hasin D, Degenhardt L, Baillie A. Further evidence of differences in substance use and dependence between Australia and the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CDH, Pluddeman A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R. Alcohol use in South Africa: Findings from the first demographic and health survey (1998) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:91–97. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K. Prevalence of alcohol use by rural primary care outpatients in South Africa. Psychological Reports. 2006;99:176–178. doi: 10.2466/pr0.99.1.176-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Seoka P, Mashego TA. Prevalence of alcohol use in a rural South African community. Psychological Reports. 2004;95:705–706. doi: 10.2466/pr0.95.2.705-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen T, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: A follow-up study from age 8-42 for females and males. Addiction. 2005;100:652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Rehn N, Room R, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Jernigan J, Frick U. The global distribution of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking. European Addiction Research. 2003;9:147–156. doi: 10.1159/000072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Buscholz KK, Heath AC. Genetic and environmental influences on the rate of progression to alcohol dependence in young women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:632–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Norman R, Parry C, Bradshaw D, Plüddemann A the South African Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Estimating the burden of disease attributable to alcohol use in South Africa in 2000. South African Medical Journal. 2007;97:664–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Williams DR, Kessler RC. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: A scientific base for mental health policy. South African Medical Journal. 2009;99:337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heerden MS, Grimsrud AT, Seedat S, Myer L, Williams DR, Stein DJ. Patterns of substance use in South Africa: Results from the South African Stress and Health Study. South African Medical Journal. 2009;99:358–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CL, Mertens JR, Flischer AJ, Bresick GF, Sterling SA, Little F, Weisner CM. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among South African primary care patients. Substance Use and Misuse. 2008;43:1395–1410. doi: 10.1080/10826080801922744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield JB, Zhu G, Madden PA, Neale MC, Heath AC, Martin NG. The genetics of alcohol intake and of alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1153–1160. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134221.32773.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Herman A, Kessler RC, Sonnega J, Seedat S, Stein, DJ, Wilson CM. The South Africa Stress and Health Study: Rationale and design. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2004;19:135–147. doi: 10.1023/b:mebr.0000027424.86587.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Herman A, Stein DJ, Heeringa SG, Jackson PB, Moomal H, Kessler RC. Twelve-month mental disorders in South Africa: Prevalence, service use and demographic correlates in the population-based South African Stress and Health Study. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:211–220. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10: The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Second Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]