Abstract

In 100 primary colorectal carcinomas, we demonstrate by array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) that 33% show DNA copy number (DCN) loss involving PARK2, the gene encoding PARKIN, the E3 ubiquitin ligase whose deficiency is responsible for a form of autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. PARK2 is located on chromosome 6 (at 6q25–27), a chromosome with one of the lowest overall frequencies of DNA copy number alterations recorded in colorectal cancers. The PARK2 deletions are mostly focal (31% ∼0.5 Mb on average), heterozygous, and show maximum incidence in exons 3 and 4. As PARK2 lies within FRA6E, a large common fragile site, it has been argued that the observed DCN losses in PARK2 in cancer may represent merely the result of enforced replication of locally vulnerable DNA. However, we show that deficiency in expression of PARK2 is significantly associated with adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) deficiency in human colorectal cancer. Evidence of some PARK2 mutations and promoter hypermethylation is described. PARK2 overexpression inhibits cell proliferation in vitro. Moreover, interbreeding of Park2 heterozygous knockout mice with ApcMin mice resulted in a dramatic acceleration of intestinal adenoma development and increased polyp multiplicity. We conclude that PARK2 is a tumor suppressor gene whose haploinsufficiency cooperates with mutant APC in colorectal carcinogenesis.

Keywords: array, comparative genomic hybridization, mouse model, PARKIN

Genomic instability in colorectal cancer (CRC) is frequently indicated by losses and gains in large portions of chromosomes, but may also be manifested in small genomic regions. Analysis of the genomic changes in a large series of CRCs for alterations in DNA copy number (DCN) across the whole genome has demonstrated the existence of restricted localized regions of DCN change (1). Here, we select chromosome 6 for detailed examination due to the relatively low prevalence of DCN changes to this chromosome in CRC and identify the PARK2 gene as affected by small, intragenic deletions in a high proportion of CRC.

PARK2 has previously been associated with the pathogenesis of familial Parkinson disease in early-onset autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinsonism (AR-JP) (2). It encodes a multifaceted protein, PARKIN, that contains a ubiquitin-like (UBL) C-terminal domain and a cysteine-rich RING-IBR-RING N-terminal motif and functions as an E3-ubiquitin ligase (3–5). PARK2 lies at 6q26 within FRA6E, one of the common fragile sites (CFSs) (6). CFSs are characterized as regions prone to DNA breakage under conditions of replicative stress. Thus, one minimalist explanation for restricted DCN changes within CFSs is that they are epiphenomena, attributable to chromosome damage secondary to the replicative stress imposed by carcinogenesis (7). However, other genes, such as FHIT and WWOX, that lie within the CFSs FRA3B and FRA16D, respectively, have already been shown by functional studies to act as tumor suppressor genes in multiple cancers including lung, kidney, myeloma, and cervix (reviewed in ref. 8). Here, we provide both in vitro and in vivo evidence that PARK2 can act as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor.

Results

Focal Copy Number Abnormalities in Colorectal Cancer Genomes.

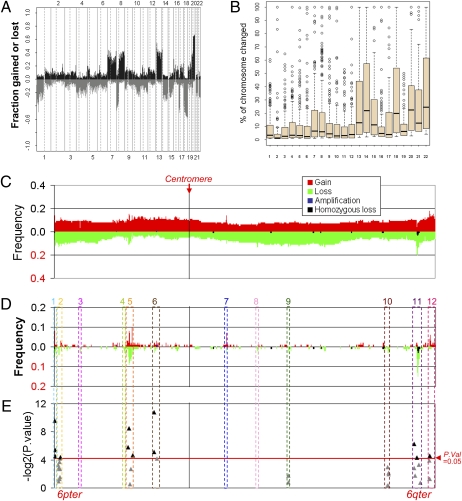

Array-CGH analysis (1Mb pan-genomic array) of the DCN changes across the whole genome in more than 100 primary CRCs inclusive of the present set (1) had identified large contiguous DCN alterations spanning many megabases, with frequent losses at 1p, 8p, 17p, and 18q, and gains at 7, 8q, 13q, and 20q (Fig. 1A). Focal deletions (∼7.7 Mb) of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) at 5q22.2, PTEN at 10q23.31, and amplifications (∼8.3 Mb) of MYC at 8q24.21 and SRC at 20q11.23 were also identified.

Fig. 1.

Genome and transcriptome alterations in CRCs. (A) Overall frequencies of DCN alterations (y axis) as assessed by 1 Mb array-CGH in >100 CRC tumors, plotted by chromosome position (x axis) with gains (black) above and losses (gray) below the x axis zero line (1). (B) Boxplots indicating the distribution of the lesion sizes (y axis, plotted as % of chromosome affected) of DCN changes for each chromosome (x axis). (C) Summary of the frequencies of DCN alterations of chromosome 6 clones by tiling-path array-CGH in 100 CRC tumors. Clones are plotted along the x axis from 6pter (Left) to 6qter (Right). The proportion (y axis) of tumors showing gains (red) or losses (green), amplifications of four or more copies (dark blue), and homozygous losses (two copies deleted) (black) are plotted for each clone. (D) Summary of the frequencies of DCN alterations affecting only small regions (≤20 consecutive clones) identified in chromosome 6. The most frequent changes are highlighted by numbered boxes (1–12). (E) Negative log2-transformed P values obtained from the Pearson correlation analyses of the expression-SNP data from Reid et al. (15) that are present within the 12 regions identified by tiling-path array CGH as the smallest and most frequent DCN alterations on chromosome 6.

To identify CRC-related genes within smaller, focal chromosomal rearrangements we developed an algorithm to count the number of consecutive bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that were altered along each chromosome (Fig. S1A) relative to the chromosome length. The distributions of the sizes of DNA regions affected by DCN alterations across all chromosomes in this set of primary CRCs (1) showed that the chromosomes with the smallest median proportions affected by DCN alterations were chromosomes 2 (median = 1.23%), 6 (2.35%), and 10 (2.82%) (Fig. 1B). The frequencies of DCN changes were plotted from similar resolution array-CGH data derived from 49 CRC lines (9) and 51 hepatic resections of metastatic CRC (10) (Fig. S1 B and C) showing similar patterns of rearrangement. Chromosome 6 was found to have a low prevalence of DCN changes across all three datasets, indicating that high-resolution genomic profiling of this chromosome might reveal DCN changes sufficiently small to identify single cancer-associated genes.

Chromosome 6 tiling-path aCGH analysis of 100 primary CRCs was performed and the overall frequencies of copy number changes were plotted (Fig. 1C). As anticipated from our genomewide analysis and analyses performed by others (9, 11, 12) few CRCs showed gains or losses of chromosome 6 extending over the whole or a large part of the chromosome. An interesting pattern emerged when the search for DCN abnormalities was restricted to small genomic regions, here operationally defined as those that occupied less than 20 adjacent consecutive/overlapping clones (≈0.1–2 Mb). Twelve regions were identified as showing changes in DCN of small genomic regions in more than 3% of the tumors studied (Fig. 1D and Table S1). The most frequent DCN alteration was detected for region 11 at 6q26, where over 28% of DCN losses lay within a region no larger than 1.2 Mb, entirely within PARK2. One closely adjacent small deletion overlay the promoter region common to PARK2 and its head-to-head partner PACRG. Another region frequently affected by short deletions overlay the MHC loci on chromosome 6p21.3–22.3. Unlike the PARK2 deletions, however, this region included several clone sites at which amplification as well as deletion were observed, perhaps reflecting selective pressure for a variety of genomic abnormalities at this site, concordant with existing data on MHC expression abnormalities in CRC (13, 14).

We further explored the influence of DCN changes on expression of the genes located within these 12 regions. An integrative approach was used to correlate the expression profiles and the genomic copy number data from SNP arrays previously produced in a set of 48 primary CRC tumors (15) (Fig. 1E). There was a significant correlation between PARK2 mRNA expression and DCN loss (P = 0.04). As a comparison, the best correlation was between PTK7 expression and DCN gain (P < 0.001). Increased expression of PTK7 (also known as colon carcinoma kinase-4, CCK-4), has previously been shown in various cancers including CRC (16).

Genetic Alterations of PARK2 in CRC Primary Tumors and Cell Lines.

Chromosome 6 tiling-path array-CGH was also used to analyze a group of CRC cell lines (DLD1, HCT116, LoVo, SW620, and HT29) previously studied by spectral karyotyping (SKY) and conventional metaphase CGH (11). As detected by these three methods, the overall pattern of DCN changes of large size was very similar. However, the high resolution array revealed several additional microdeletions and microgains including DCN loss within PARK2 in 2 of the 5 CRC cell lines (SW620 and HT29) (Fig. S2 B1 and B2). The skygram of HT29 (11) suggested a complex translocation involving chromosomes 6 and 14 (Fig. S3 A and B). The data described here show that the gene mapping to the distal 6q breakpoint of this translocation is PARK2 (Fig. S3C).

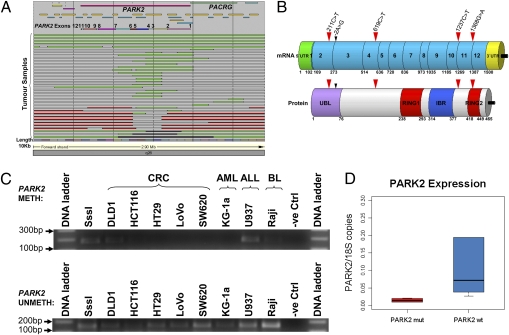

In all, of the 100 sporadic CRCs studied by chromosome 6 tiling-path array-CGH, 33 showed DCN changes suggestive of local allelic loss affecting PARK2 (Fig. 2A). A total of 25 were heterozygous, whereas 3 appeared to be homozygous (3%). A further 5 showed DCN loss within a much longer region of DCN gain, bringing the total proportion of this set of primary CRCs with evidence of DCN loss affecting PARK2 to 33% (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

(A) Schematic representation of the DCN changes detected at 6q26 by tiling-path aCGH. Green bars indicate heterozygous deletions; red bars indicate gains; black bars indicate homozygous deletions; white/transparent bars indicate retention of two alleles. The numbers above the colored boxes (Upper) indicate the PARK2 exons. The most frequent deletion events target exons 3 and 4 of PARK2. (B) Summary of somatic mutations of PARK2 found in CRC primary tumors and cell lines. The location and type of the mutations is shown by the red arrows in relation to the cDNA (Upper) and protein (Lower). The black arrow indicates an intronic change at the splice site (−2A > G) between exons 2 and 3. (C) MSP analysis of the CpG islands of the PARK2 promoter in cancer-derived cell lines. The cancer cell lines DLD1, U937, and Raji showed amplification of a methylated allele of the PARK2 promoter (Upper), whereas all of the samples showed amplification of the product corresponding to the unmethylated PARK2 promoter (Lower). (D) Boxplot indicating the relative transcript levels of PARK2 expression in PARK2 wild-type versus mutated PARK2 bearing CRC primary tumors.

In three tumors, gene scan analysis of PCR-amplified DNA at seven microsatellite markers distributed across PARK2 confirmed the presence of allelic imbalance in the regions of heterozygous deletion indicated by the array-CGH profiles and allelic balance in the regions of homozygous deletion (Fig. S4).

Mutation and Methylation Studies of the PARK2 Gene.

To further evaluate whether there are mutations in the retained alleles of PARK2, as expected of a classical tumor suppressor gene, DNA sequence was obtained from all reported PARK2 exons and splice sites. The methylation status of the PARK2 promoter was also analyzed by methylation specific PCR (MSP). In this analysis, all cases in which there were DCN alterations in PARK2 (n = 33) were included, as well as 5 CRC lines and 10 further primary CRCs with no DCN change in PARK2. Sequence alterations were verified as somatically acquired by examination of the corresponding sequence in genomic DNA from normal tissue. Five somatic PARK2 point mutations were found, one in a primary CRC with no alteration in the corresponding normal tissue, and four in the CRC lines LoVo and DLD1 (two mutations in each line) (Fig. 2B). None of these mutations corresponded to any currently reported SNPs. One (211C > T, found in LoVo) was in exon 2, within the UBL domain (Pro37Leu) (Fig. S5) a region previously shown to be required for the interaction between PARKIN and its ligands or the proteasome (17). Notably, this mutation has been found in the germline of a patient with AR-JP (18). We also identified two primary CRCs with hypermethylation of the PARK2 promoter. Interestingly, one of these (H18), also had the only point mutation that we identified in a primary CRC, 619C > T in exon 4 (Thr173Ile). PARK2 promoter hypermethylation was also detected in DLD1 (a CRC cell line) and in the ALL cell line U937 and BL cell line Raji (Fig. 2C), consistent with the reported high frequency of PARK2 promoter hypermethylation in leukemia/lymphoma cell lines (19).

Expression Analysis of PARK2.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed to measure the transcript levels of PARK2 in a representative set of CRC primary tumors with deleted PARK2 (n = 6) versus wild-type (WT) PARK2 (n = 6). PARK2 transcript levels were significantly lower (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.002) in the tumor samples with deleted PARK2 versus wild-type PARK2 (Fig. 2D).

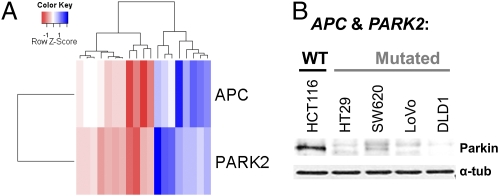

The transcriptional profiles of microdissected CRCs in a previously published database (20) were analyzed to compare the group lower than the 50th percentile with the group higher than the 50th percentile in terms of PARK2 expression. A key gene that was differentially expressed (P = 0.006) between these two groups was APC, a regulator of Wnt signaling that is mutated in 60–80% of sporadic CRCs and in the germline of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis coli. Pearson's correlation analysis showed that the expression of APC was significantly (P < 0.001) correlated with PARK2 expression indicating that these genes are down-regulated in concert (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, PARKIN protein levels were significantly lower in all of the CRC cell lines with deleted or mutated PARK2 compared with HCT116, the only CRC line in which we demonstrated neither DCN alterations, point mutations nor PARK2 promoter hypermethylation (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Concordant expression of PARK2 and APC in primary CRCs and CRC cell lines. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and heatmap of PARK2 and APC relative transcript levels in microdissected CRC show concordant changes for these two transcripts. (B) Western blot indicating PARKIN protein expression in the APC and PARK2 WT (HCT116) and mutant (HT29, SW620, LoVo, DLD1) CRC cell lines.

PARK2 Overexpression Inhibits Cell Proliferation.

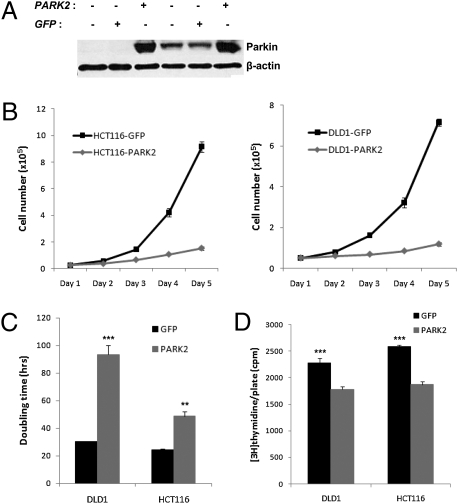

Stable cell lines overexpressing PARK2 were made to test the hypothesis that altered PARK2 expression affects colon cancer cell proliferation. Given the concordant expression of PARK2 and APC levels in primary CRC tumors and cell lines, we tried to identify whether there is a differential effect of PARK2 overexpression on cell proliferation in the presence or absence of a background APC mutation. Thus, we used the well-characterized APC-deficient DLD1 and APC-wild-type HCT116 CRC cell lines. Both DLD1 and HCT116 cells stably expressing PARK2 showed a dramatic decrease in cell proliferation compared with GFP controls (Fig. 4 A and B). The effect was more profound in the APC-deficient DLD1 cell line, where the doubling time of the PARK2-expressing cells was significantly increased by ∼3-fold compared with GFP controls, whereas the corresponding difference in the HCT116 cells was ∼2-fold (Fig. 4C). The reduction of cell proliferation was confirmed by a lower proportion of PARK2-expressing cells (both HCT116 and DLD1) entering S phase compared with GFP controls, as evidenced by the significantly lower rates of [3H]thymidine incorporation (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

PARK2 overexpression is associated with decreased cell proliferation. (A) Immunoblotting of DLD1 and HCT116 cells stably expressing GFP control and PARK2-expressing lentiviral constructs. (B) Proliferation curves, (C) doubling times, and (D) rates of [3H]thymidine incorporation of the PARK2-overexpressing and GFP-control HCT116 and DLD1 cells. Error bars denote SEM from triplicate experiments; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Heterozygous Park2 Deletion Accelerates Intestinal Adenoma Development in ApcMin Mutant Mice.

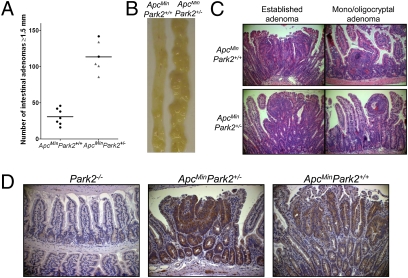

The concordant reduction in the transcriptional levels of PARK2 and APC in CRCs (Fig. 3) and the more dramatic antiproliferative effect of PARK2 overexpression on the APC-deficient DLD1 cell line suggested a possible functional relationship between the two genes. To test this hypothesis, mice with a targeted knockout of exon 3 of Park2 (21) were crossed with Apc+/Min mice with an Apc mutation at codon 850 (22). Although Park2+/−/Apc+/+ mice did not form intestinal adenomas, Park2+/−/Apc+/Min mice showed an approximately 4-fold increase in adenoma prevalence in the intestines when compared with control Park2+/+/Apc+/Min littermates (P < 1 × 10−4, Student's t test) (Fig. 5 A and B). Furthermore, there was earlier development of all stages of intestinal neoplasm including monocryptal, oligocryptal, and established adenomas in Park2+/−/Apc+/Min, with a median harvest time of the murine intestines obstructed by adenomas at 12 wk instead of 16 wk for the Park2+/+/Apc+/Min mice. Equivalent neoplasms from both cohorts showed the same degree of moderate dysplasia in the established adenomas (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

PARK2 loss accelerates intestinal adenoma development in ApcMin mice. (A) Significantly higher prevalence (y axis) of macroscopic intestinal adenomatous polyps (greater than 1.5 mm in diameter) in Park2+/− (n = 6) mice compared with Park2+/+ (n = 7) mice bred on to an Apc+/Min background (circles, 16–wk-old mice; triangles, 12-wk-old mice). (B) Macroscopic photographs of Apc+/Min/Park2+/+ and Apc+/Min/Park2+/− murine small intestines at 12–16 wk of age, showing many more adenomatous polyps in the latter cohort. (C) Photomicrographs of H&E stained mono/oligocryptal and established adenomas from Apc+/Min/Park2+/+ and Apc+/Min/Park2+/− mice at 12–16 wk of age, showing similar appearances. (D) Photomicrographs of Parkin immunohistochemically stained normal mucosa from Park2 homozygous knockout mice (Left), adenomas from Apc+/Min/Park2+/− (Center), and Apc+/Min/Park2+/+ (Right) mice (all sections shown are magnifications 200×).

Parkin protein expression was examined by immunohistochemistry on adenoma sections derived from these mice. Although Parkin protein expression is completely absent in sections of normal colonic epithelium of Park2−/− mice (Fig. 5D), normal intestinal mucosa of both Park2+/+/Apc+/Min and Park2+/−/Apc+/Min mice showed Parkin immunohistochemical expression in the cytoplasm of the epithelial cells at moderate intensity in the crypts and only weakly in the villi. The wild-type Park2 allele appears to be retained in the tumors of the Park2 heterozygous mice, as adenomas from both Park2+/−/Apc+/Min (28/30 polyps, 93%) and Park2+/+/Apc+/Min (34/35 polyps, 97%) mice showed moderate levels of Parkin immunohistochemical expression (Fig. 5D), suggesting that Park2 acts as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Finally, immunohistochemical analysis of β-catenin protein expression and localization showed that both Park2+/−/Apc+/Min and Park2+/+/Apc+/Min adenomas had greater than 20% β-catenin staining localized to the nuclei in 26/30 (87%) and 33/35 (94%), respectively, confirming very similar patterns of aberrant Wnt signaling in both cohorts (Fig. S6).

Discussion

We show here that PARK2 is subject to DCN loss in around one third of sporadic CRCs. In more than 28% of affected tumors the region of DCN extends for less than 1.2 Mb, is usually heterozygous, and most commonly affects exons 3–4. These features are similar to those in a recently reported series of sporadic CRCs and glioblastomas (23). Point mutations in PARK2 are rare in CRC: we found none in 33 primary tumors carrying PARK2 deletions and only 1 in 10 tumors without deletion. However, of four mutations in two CRC cell lines at least one (211C > T) is presumptively functional, as an identical mutation has been recorded in the germline of a kindred with AR-JP and has been predicted to compromise PARKIN–proteasome interactions (Fig. S5) (18). In CRC, the high frequency of small deletions in PARK2 relative to point mutations, and the predilection for DCN loss involving exons 3 and 4, are also broadly similar to the spectrum of germline alterations in juvenile Parkinson disease (24).

PARK2 promoter hypermethylation was also observed, albeit infrequently, as an alternative mode of silencing PARK2, whereas quantitative RT-PCR analysis confirmed the reduction in PARK2 transcript levels in a small subset of CRCs with mutant or deleted PARK2.

A recent, large, genomewide study of DCN alterations in cancers suggests that radically different selection pressures are responsible for the different patterns of allelic deletion found in classical tumor suppressor genes on one hand and in genes that happen to span fragile sites on the other (25). According to this logic, the biallelic suppression of tumor suppressor genes that is widely considered necessary for driving carcinogenesis, results in DCN loss that is commonly homozygous, or if hemizygous is frequently associated with evidence of some other mechanism for silencing the retained alleles, such as point mutation or promoter methylation. In contrast, predominantly heterozygous deletions, unaccompanied by point mutations or promoter methylation, as found in PARK2, is a pattern identical to that of other large genes at common fragile sites, such as WWOX and FHIT, and may merely reflect the result of enforced replication cycles at intrinsically vulnerable genomic locations. In this paper, however, we show clearly that heterozygotic PARK2 deletion cooperates with APC suppression to accelerate tumor progression. Thus, although we are aware of no records of enhanced intestinal neoplasia in any of the strains of Park2-deficient mice currently available, mice with heterozygous inactivation of both APC and PARK2 have greatly accelerated adenoma growth when compared with siblings with APC mutation alone, with evidence of expression of the retained wild-type Park2 allele and aberrant Wnt signaling in the adenomas. In parallel, using a bioinformatic approach applied to published data (20), we showed that microdissected human CRC tissue demonstrates coordinate suppression of APC and PARK2 expression. Furthermore, PARK2 overexpression inhibits cell proliferation in CRC cell lines and the effect is more prominent in the APC-deficient DLD1 cell line.

The data presented here suggest a pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis in which the initiating event provided by suppression of a classical tumor suppressor (APC) selects for a subsequent enhancing lesion (haploinsufficiency of PARK2 expression). Data describing intragenic PARK2 DCN loss in glioblastoma (23) and carcinomas of ovary (26), lung (23, 27), and breast (27, 28) suggest that PARK2 may play a similar role in a wide spectrum of common cancers. It is intriguing that Parkinson's disease patients have a higher risk for at least one cancer type—that of melanomas (29), suggesting the possible contribution of PARK2 loss/mutation in the initiation of this cancer.

Doubt still remains as to the mechanisms adopted by PARKIN, the PARK2 product, in effecting this tumor-suppressor function. Much of the published literature regarding PARKIN is concerned with its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, the absence of which leads to intraneuronal accumulation of intracytoplasmic insoluble aggregates of synuclein, nucleophysin, and other proteins, forming the pathognomonic Lewy bodies (30, 31). Lewy bodies are not a feature of CRC, however, and other potential targets of PARKIN's E3 ubiquitin ligase activities should be considered. Cyclin E is one such target molecule and its accumulation in PARKIN-depleted cells because of delayed proteolysis could provide a stimulus toward adenoma growth and mitotic instability (23, 31). Perhaps related is the observation that ectopic expression of PARK2 in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines retarded growth in vitro and was associated with increased sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents (32).

PARKIN's E3 ligase functions include both mono- and polyubiquitination, and hence may involve regulation of protein localization and intracellular trafficking as well as proteasomal proteolysis (17, 33–37). PARKIN has also been implicated in the binding and stabilization of microtubules (38) and in the biogenesis of mitochondria, where it localizes in proliferating cells (39). It is also a key player supporting the repair of mitochondrial DNA (40) and in the identification and autophagy of damaged mitochondria (41). Concordantly, the mitochondria of Park2-null mice are deficient in respiratory capacity, showing age-dependent accumulation of hydroxynonenal, a biomarker of damage to lipid membranes by reactive oxygen intermediates (42). Hence, PARK2 mutations are predicted to lead to accumulation of defective mitochondria and possibly altered susceptibility to apoptosis.

Following the identification of PARK2 as a target for intragenic deletion in about one third of CRCs, we have validated PARK2 as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor, demonstrating cooperation between PARK2 deletion and mutated APC. The mechanism underlying this cooperation remains to be elucidated, but PARKIN has been shown to ubiquitinate and promote the degradation of the nuclear pore complex protein RANBP2 (43), the accumulation of which results in enhanced Wnt signaling with increased expression of the Wnt target genes cyclin D1 and c-myc (44).

Materials and Methods

Primary Colorectal Tumor Samples, Cell Lines, and DNA/RNA Extraction.

As described previously (1), fresh frozen tissue from surgically resected colons was collected from 100 CRC patients, generating a sample set of paired tumor and normal tissues for DNA and RNA extraction. Patient consent was obtained in accordance with local ethical committee guidelines and samples were anonymized at collection. Subconfluent cultures of CRC cell lines HCT116, LoVo, DLD1, SW620, and HT29, were grown in 100-mm dishes as previously described (11). DNA and RNA were extracted using the QIAamp DNA and RNeasy minikit protocols, (Qiagen), respectively.

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization.

The chromosome 6 tiling-path resolution array was constructed using BAC clones obtained from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Array hybridization and data analysis was performed as previously described (45). The bioinformatic analysis of genome and transcriptome data are described in detail in SI Materials and Methods.

Mutation Detection and Methylation Analysis of the PARK2 Gene and Promoter.

Samples that were identified as showing DCN alterations of the PARK2 gene (n = 33) and the cell lines HCT116, LoVo, DLD1, SW620, and HT29 were subjected to mutational screening by PCR amplification of all coding exons followed by capillary sequencing as previously described (24). MSP was used to detect CpG methylation of the promoter region of the PARK2 gene (Table S2).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was reverse transcribed using the QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). Real-time analysis of PARK2 transcripts was performed using a LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics) essentially as described previously (46) using primer pairs binding to exons 3 and 4 of PARK2. The 18S ribosomal RNA gene was used as an internal reference for expression analysis. Six samples with deleted PARK2 were compared with six samples with wild-type PARK2.

Lentiviral Transfections and in Vitro Proliferation Assays.

A Gateway compatible lentivirus vector was constructed through the insertion of a Gateway cloning system reading frame cassette into the pDONR221 vector (Invitrogen) that was then transferred into the pLenti 6.2 (Invitrogen) expression vector as described previously (47). For the proliferation assays, HCT116 and DLD1 cells were seeded in triplicate in 6-well plates, at densities of 5 × 104 and 1 × 105 per well, respectively, and were counted after trypsinization at days 1–5. The DNA synthesis assay was performed on tritiated [3H]thymidine (0.8 microcuries/mL)-treated cells and radioactivity was counted in radioactive scintillation fluid (Beckman LS6000SC).

Immunoblotting.

Cells were lysed in buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/mL Leupeptin, and 1 mM DTT. Western blotting was performed with the following antibodies: anti-Parkin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-32282), anti-β-actin (Abcam, ab6276), and anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, T6199).

Analysis of Intestinal Adenomas in Park2+/− ApcMin Mice.

Park2+/− mice (heterozygous for deletion of Park2 exon 3) (21) were crossed with ApcMin mice (bearing a codon 850 mutation in the Apc gene) (22) on a C57BL/6J background. Mice were genotyped by PCR for ApcMin and Park2 alleles as described previously (21, 22, 48). The intestines of tumor watch mice were macroscopically dissected to determine the number and location of adenomas in the small and large intestines at 12–16 wk of age. The intestines were then prepared as Swiss rolls (49) and processed for histological analysis. Sections 5 μm thick were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Suet Y. Leung and Prof. Siu T. Yuen (University of Hong Kong) and Prof. David J. Harrison (University of Edinburgh) for providing all the material and clinical data of the tumors included in this study. This work was supported by the Addenbrooke's Charitable Trust, the John Lucas Walker Fund, Cancer Research-UK, a research award from the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1009941107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Poulogiannis G, et al. Prognostic relevance of DNA copy number changes in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2010;220:338–347. doi: 10.1002/path.2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitada T, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imai Y, Soda M, Takahashi R. Parkin suppresses unfolded protein stress-induced cell death through its E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35661–35664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimura H, et al. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet. 2000;25:302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, et al. Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin-protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13354–13359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240347797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland GR, Richards RI. The molecular basis of fragile sites in human chromosomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:323–327. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorgoulis VG, et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DI, McAvoy S, Zhu Y, Perez DS. Large common fragile site genes and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas EJ, et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization analysis of colorectal cancer cell lines and primary carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4817–4825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta KR, et al. Fractional genomic alteration detected by array-based comparative genomic hybridization independently predicts survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1791–1797. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel-Rahman WM, et al. Spectral karyotyping suggests additional subsets of colorectal cancers characterized by pattern of chromosome rearrangement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2538–2543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041603298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diep CB, et al. The order of genetic events associated with colorectal cancer progression inferred from meta-analysis of copy number changes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:31–41. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaklamanis L, et al. Loss of HLA class-I alleles, heavy chains and beta 2-microglobulin in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 1992;51:379–385. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiman JM, Kmieciak M, Manjili MH, Knutson KL. Tumor immunoediting and immunosculpting pathways to cancer progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reid JF, et al. Integrative approach for prioritizing cancer genes in sporadic colon cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:953–962. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saha S, et al. A phosphatase associated with metastasis of colorectal cancer. Science. 2001;294:1343–1346. doi: 10.1126/science.1065817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakata E, et al. Parkin binds the Rpn10 subunit of 26S proteasomes through its ubiquitin-like domain. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:301–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mata IF, Lockhart PJ, Farrer MJ. Parkin genetics: One model for Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(Spec No 1):R127–R133. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agirre X, et al. Abnormal methylation of the common PARK2 and PACRG promoter is associated with downregulation of gene expression in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1945–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staub E, et al. An expression module of WIPF1-coexpressed genes identifies patients with favorable prognosis in three tumor types. J Mol Med. 2009;87:633–644. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0467-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itier JM, et al. Parkin gene inactivation alters behaviour and dopamine neurotransmission in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2277–2291. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su LK, et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veeriah S, et al. Somatic mutations of the Parkinson's disease-associated gene PARK2 in glioblastoma and other human malignancies. Nat Genet. 2009;42:77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West AB, Maidment NT. Genetics of parkin-linked disease. Hum Genet. 2004;114:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bignell GR, et al. Signatures of mutation and selection in the cancer genome. Nature. 2010;463:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature08768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denison SR, Callahan G, Becker NA, Phillips LA, Smith DI. Characterization of FRA6E and its potential role in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism and ovarian cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:40–52. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picchio MC, et al. Alterations of the tumor suppressor gene Parkin in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2720–2724. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cesari R, et al. Parkin, a gene implicated in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism, is a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 6q25-q27. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5956–5961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931262100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Driver JA, Logroscino G, Buring JE, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. A prospective cohort study of cancer incidence following the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1260–1265. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimura H, et al. Ubiquitination of a new form of alpha-synuclein by parkin from human brain: Implications for Parkinson's disease. Science. 2001;293:263–269. doi: 10.1126/science.1060627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staropoli JF, et al. Parkin is a component of an SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex and protects postmitotic neurons from kainate excitotoxicity. Neuron. 2003;37:735–749. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujiwara M, et al. Parkin as a tumor suppressor gene for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:6002–6011. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doss-Pepe EW, Chen L, Madura K. Alpha-synuclein and parkin contribute to the assembly of ubiquitin lysine 63-linked multiubiquitin chains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16619–16624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413591200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fallon L, et al. A regulated interaction with the UIM protein Eps15 implicates parkin in EGF receptor trafficking and PI(3)K-Akt signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:834–842. doi: 10.1038/ncb1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hampe C, Ardila-Osorio H, Fournier M, Brice A, Corti O. Biochemical analysis of Parkinson's disease-causing variants of Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase with monoubiquitylation capacity. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2059–2075. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim KL, et al. Parkin mediates nonclassical, proteasomal-independent ubiquitination of synphilin-1: Implications for Lewy body formation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2002–2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4474-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vives-Bauza C, et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang F, et al. Parkin stabilizes microtubules through strong binding mediated by three independent domains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17154–17162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuroda Y, et al. Parkin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis in proliferating cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:883–895. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothfuss O, et al. Parkin protects mitochondrial genome integrity and supports mitochondrial DNA repair. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3832–3850. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geisler S, et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palacino JJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18614–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Um JW, et al. Parkin ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of RanBP2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3595–3603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shitashige M, et al. Regulation of Wnt signaling by the nuclear pore complex. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1961–1971. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichimura K, et al. Small regions of overlapping deletions on 6q26 in human astrocytic tumours identified using chromosome 6 tile path array-CGH. Oncogene. 2006;25:1261–1271. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ichimura K, et al. 1p36 is a preferential target of chromosome 1 deletions in astrocytic tumours and homozygously deleted in a subset of glioblastomas. Oncogene. 2008;27:2097–2108. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawano Y, et al. A lentiviral cDNA library employing lambda recombination used to clone an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-induced cell death. J Virol. 2004;78:11352–11359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11352-11359.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo F, et al. Mutated K-ras(Asp12) promotes tumourigenesis in Apc(Min) mice more in the large than the small intestines, with synergistic effects between K-ras and Wnt pathways. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90:558–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moolenbeek C, Ruitenberg EJ. The “Swiss roll”: A simple technique for histological studies of the rodent intestine. Lab Anim. 1981;15:57–59. doi: 10.1258/002367781780958577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.